Violence toward emergency physicians: A prospectivedescriptive study

Kasım Turgut, Erdal Yavuz, Mine Kayacı Yıldız, Mehmet Kaan Poyraz

Department of Emergency Medicine, Research and Training Hospital, Adiyaman University, Adiyaman 02100, Turkey

KEYWORDS: Violence; Emergency physician; Emergency department

INTRODUCTION

Workplace violence re fers to a physical and/or psychological attack to which a person is exposed while working. This may be verbal or physical (armed or unarmed), resulting in injury or even death.[1]In addition,employees’ reduced motivation caused by such an attack and their lack of security may reduce their work efficiency or cause them to resign from their job.[2]

The highest rate of exposure to workplace violence is seen in healthcare institutions (25%).[1]Studies have also shown that most of the violence witnessed in the health sector is either unreported or overlooked. In particular,the employees of emergency services, psychiatric services, and the services where dementia patients are examined face the highest level of violence. Among health workers, doctors and nurses constitute the group that is most exposed to violence.[1,3]The overcrowded and noisy environment of emergency services, long waiting time, presence of very anxious patient relatives, sudden onset and severe complaints of emergency patients, and physicians not being able to fully attend to the patients’needs create tension, which is reflected as violence on doctors and nurses in the vicinity.[4]Emergency service employees are more likely to be exposed to violence than other healthcare workers.[5]These acts of violence are mostly verbal, and they are committed by the relatives of patients in the waiting room.[1]

Many studies in the literature have investigated violence toward healthcare workers.[1,2,6]In most of these studies, the data were collected by administering questionnaires to doctors and nurses who had been exposed to violence. In contrast, in the current study,we aim to determine the characteristics and causes of violence toward emergency physicians by interviewing not only the physicians exposed to such behavior but also the patients and their relatives who had displayed violent behavior.

METHODS

Study setting

This prospective study was conducted in the adult emergency service of a tertiary hospital. Our emergency department (ED) provides services to an average of 25,000 patients monthly, with four physicians working at each shift.

Study protocol

The incidents of violence toward emergency physicians were examined from June 2018 to May 2019. The study was carried out in two stages. In the first stage, when an emergency physician was exposed to a violent act, a third party that was not involved in violence (doctor, nurse, or social services expert) asked the patients and their relatives to attend an interview after the situation was under control and the perpetrator had calmed down. This mediator interviewed the patient,his/her relatives, and the physician exposed to violence using questions prepared by the researchers.

The questions for the patients and their relatives responsible for the violent act were as follows: (1) what was your reason for presenting to the emergency service?;and (2) what was the cause of the problem with the emergency physician? The physicians exposed to violent behavior were directed the following questions: (1) what was the patient’s medical complaint?; and (2) what was your diagnosis? Then, the responses of the patients/patient relatives and physicians, type of violence, place and time of violence, characteristics of the perpetrator(e.g., gender and place of residence), medical outcome,duration of emergency service stay, and the patients’social health insurance were recorded in the prepared form. In our study, we included verbal and physical violent acts, but excluded sexual assault incidents. Verbal threatening, yelling, and swearing were considered as verbal violence, while pushing, kicking, scratching,punching, or pulling was evaluated as physical violence.

It was determined that the patients or relatives gave 19 different responses to the question of why they had exhibited violence toward an emergency physician.These responses were analyzed by three physicians that were not a part of the study and also not a party to the violent act (one psychiatrist and two emergency medicine specialists). As a result of this analysis, the responses given were generalized, and six different causes of violence were identified: (1) dissatisfaction with the examination or treatment method and making his/her own treatment recommendation; (2) thinking that the patient was not given enough attention by the physician, nurse, or staff; (3) long waiting time in the emergency service, (4) extremely anxious patient or patient relatives; (5) problems related to the infrastructure of the hospital; and (6) non-health-related and unethical requests of the patients.

Throughout the study, non-physician emergency service workers (nurses, security guards, technicians)were also subjected to many violent acts. However, since many of these incidents were not reported or recorded,they were not included in the study. In addition, the cases of violence due to excessive alcohol consumption or drug abuse were excluded in order to reach more precise conclusions about the causes of violence through patients who were conscious and able to communicate.Furthermore, we excluded the patients who continued to be violent, who left the emergency service immediately after the incident, and who did not want to participate in the study. In our country, in addition to private insurance schemes, there are two basic health state insurance systems. The first is the green card system, in which all healthcare costs are covered by the state without any limitation. Green cards are issued for Turkish citizens with a total income level less than one-third of the minimum wage. The second is the Social Security Institution (SSI) insurance, in which the state contributes to a percentage of healthcare costs. This is provided for civil servants, manual laborers, and tradespeople.

Statistical analysis

The data obtained from the study were analyzed using SPSS statistical software (version 17). The descriptive statistics were given as frequency, percentage,and mean±standard deviation values. Graphs were constructed to present some of the categorical variables.

RESULTS

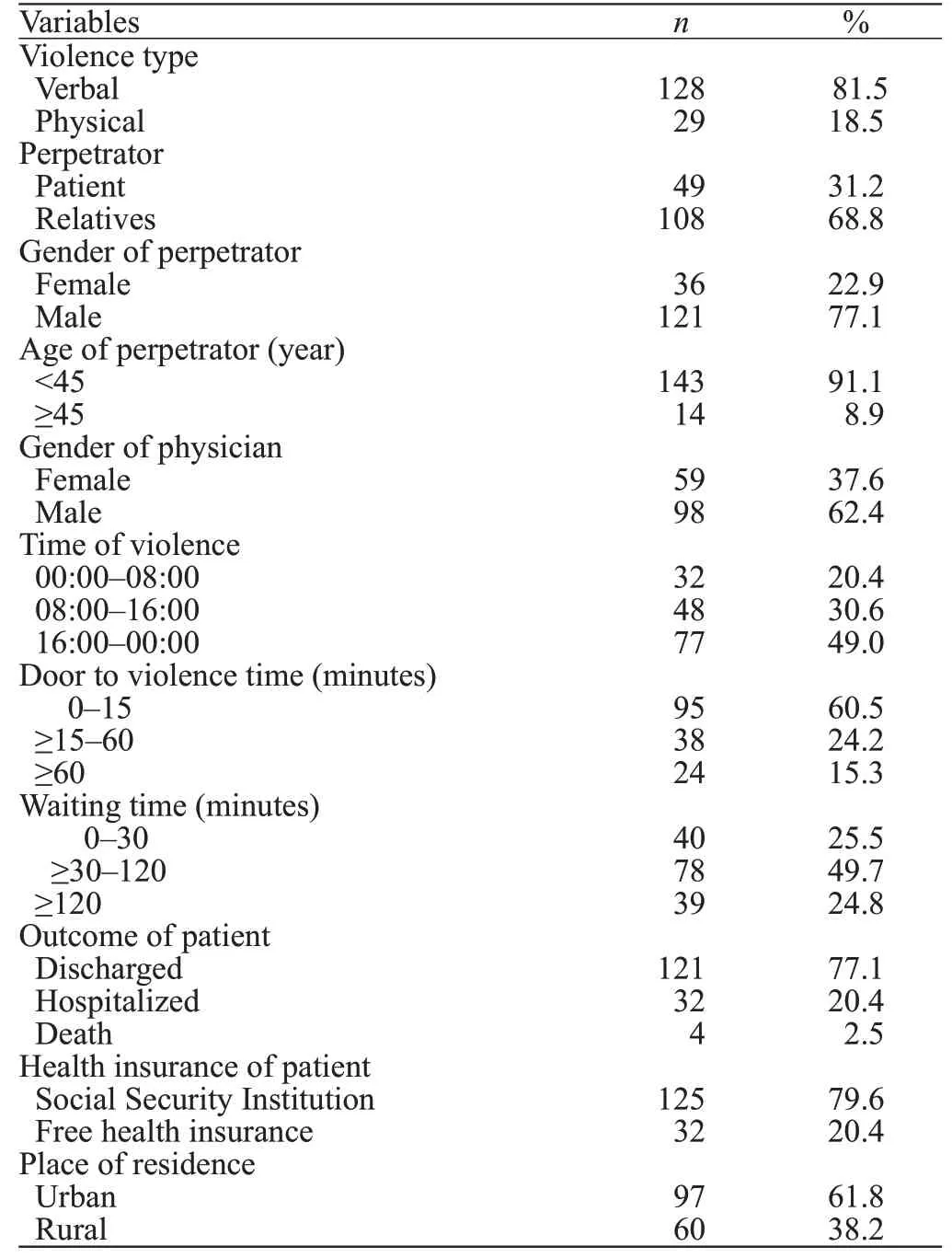

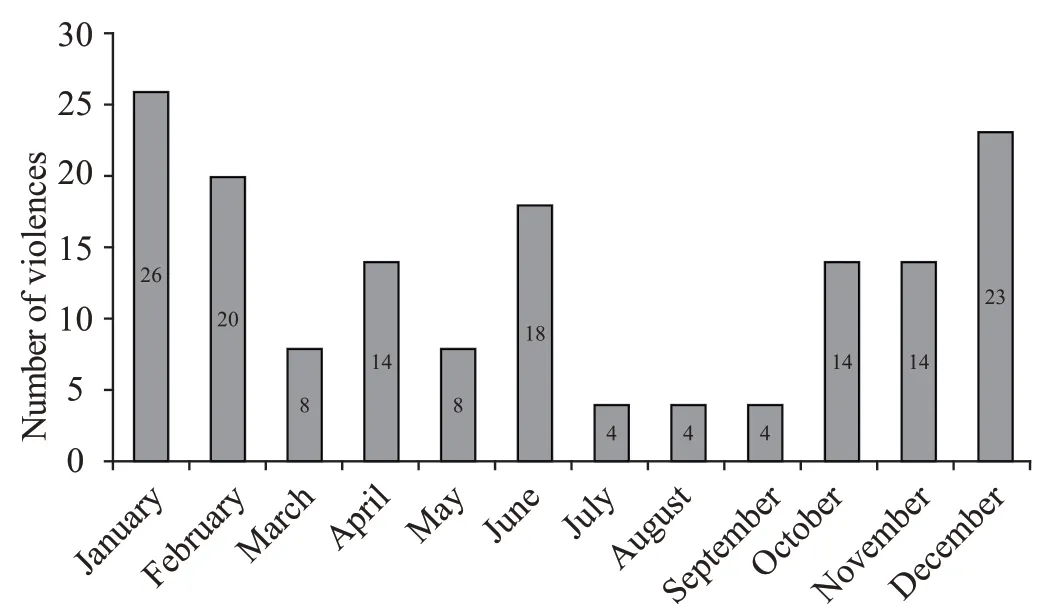

During the one-year study, there were 157 violent acts toward emergency physicians, and 81.5% were verbal. The majority were committed by males (77.1%)and patient relatives (68.8%). The age of the perpetrators was 31.9±10.2 years, with 91.1% being under 45 years.Female physicians were exposed to violence in 59 violence cases and male physicians in 98. Almost half of the violent acts (49.0%) took place from 04:00 p.m. to 00:00 a.m., followed by 8:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. (30.6%).Violence toward physicians was mostly seen within the first 15 minutes of presentation to the emergency service (60.5%), while 84.7% occurred within the first hour. Of the cases involving violence, 77.1% were discharged after the emergency intervention, 20.4%were hospitalized, and 2.5% died in the ED. Of the 29 patients who displayed physical violence, 23 (79.3%)were discharged and six were hospitalized. The waiting time in the emergency service was 98.7±88.9 minutes,and 75.2% of the patients waited for less than two hours.Concerning health insurance, 79.6% of the patients who were violent toward emergency physicians were covered by the health insurance provided by SSI and the remainder held a Turkish green card. In terms of the place of residence, 61.8% of the cases lived in urban areas, and the remainder in rural areas (Table 1). In terms of the time of a year, the incidents of violence mostly occurred in January (16.6%), December (14.7%), and February (12.7%) (Figure 1).

The reason for the violent behavior was mostly associated with the patients’ or their relatives’dissatisfaction with the method of treatment or examination and making their own treatment recommendations (n=60), followed by the presence of extremely anxious patients or patient relatives (n=26),problems related to the infrastructure of hospital (n=20),thinking that the patient was not given enough attention by physician, nurse, or staff (n=18), long waiting time in the emergency room (n=18), and non-health-related and unethical requests of the patients (n=15). Among the reasons for emergency service presentation, falls came f irst (n=36, 22.9%), followed by abdominal pain (n=27,17.2%), traffic accidents (n=25, 15.9%), sore throat(n=18, 11.5%), syncope (n=11, 7.0%), dyspnea (n=9,5.7%), chest pain (n=9, 5.7%), and other complaints(n=22, 14.0%).

Table 1. Characteristics of violence (n=157)

DISCUSSION

Violence toward healthcare workers has become an increasingly serious public health problem worldwide.[7]The gravity of this issue was evidenced by a previous study reporting that 97% and 92% of emergency service workers were exposed to verbal and physical violence,respectively, at least once in their lives. It has been repeatedly found that these violent incidents can have serious consequences, including death.[8,9]

Figure 1. Distribution of violence by months.

The causes of violence are multifaceted. From the point of physicians, burnout syndrome, feeling inadequate at their jobs, and treating patients as objects will cause communication problems with patients and their relatives, leading to violence. Furthermore, the infrastructure problems of hospitals, such as limited staffand security, overcrowded nature of emergency services,long waiting time, and violation of privacy can be considered as systemic problems.

Patients being under the effect of alcohol or drugs,personal armament, gang violence, low socio-economic level, and the feeling that patients are kept waiting in the emergency service for a long time and not receiving enough attention are other important factors that play a role in violent acts in the health field.[10,11]In Western societies, being under the inf luence of alcohol and drugs has an important share in the violence that occurs in the emergency service,[9,12]while in a study conducted in Pakistan, the lack of education, overcrowded emergency services, and insufficient security personnel are reported to be the most common causes of violence.[4]In another study, factors, such as long waiting time, dissatisfaction with the treatment, and disagreement with physicians were the main reasons identified.[13]In the current study, the reasons for the violent behavior displayed against emergency physicians were: the dissatisfaction of the patients or their relatives with the examination or treatment method, their feelings of extreme anxiety,systemic problems related to the hospital infrastructure,thinking that the patients were not given enough attention, long waiting time, and non-health-related and unethical demands of the patients or their relatives. In Turkey, patients and their relatives usually present to the ED with the prejudice that emergency physicians are novices and inadequate. Thus, they try to guide the emergency physician during the examination and treatment process in accordance with their level of knowledge and culture. This may be the reason why dissatisfaction with treatment was the most common reason behind the violent acts in this study. Because of the cultural and religious characteristics of the place where we conducted the study, violence due to alcohol and drug use was low. Considering the rarity of these cases, we deliberately excluded these incidents from the current study.

Violence toward emergency service workers is mostly verbal, and physical violence is less frequently seen. However, many emergency physicians report to have witnessed physical violence toward themselves or another emergency worker throughout their careers. In addition, it has been found that poor or no response to verbal violence can lead to physical violence. Here, it is important to consider that individuals exposed to verbal violence are significantly affected in psychological terms, and they need as much support as in victims of physical violence.[3,14,15]In a study by Kowalenko et al,[14]74.9% and 28.1% of the physicians reported verbal and physical violence, respectively. In another study, 76.2%of the physicians described verbal violence and 24.1%described physical violence.[7]In the current study, 81.5%of the violent incidents were verbal and 18.5% were physical. Studies in the literature are generally in the form of questionnaires, asking the physicians about the violence to which they have been exposed. We expect to have achieved more accurate results since the data were obtained from the interviews with the perpetrators and victims of emergency service violence immediately after the act had taken place.

In this study, the most common reasons for the patients’ presentation to the ED were falls, abdominal pain, traffic accidents, and sore throat. Of the cases investigated, 77.1% were discharged without hospitalization, and 20.4% were hospitalized. In studies revealing different patient profiles, the rate of discharge from hospital was found to be 45%[11]and 35.3%.[16]Trauma cases have the highest mortality after cardiovascular diseases and cancer,[17]and emergency services play an important role in the management of fatal trauma cases, which is confirmed by the majority of our violence cases being trauma-related. However,the majority of our patients being discharged and 15.5%having non-urgent complaints such as sore throat indicate that most cases that led to violence were not lifethreatening or did not require hospitalization.

We determined that violence was mostly perpetrated by young male patients and patient relatives. A patient relative can be a parent, blood relation, or friend that accompanies the patient to the emergency service.In some cases, there may be more than one person that wants to help the patient. This situation not only increases the overcrowded nature of the emergency service but also often leads to an increased rate of violent incidents toward healthcare workers.[4]Unlike our results, James et al[18]reported that the majority of violent incidents (88.2%) were initiated by the patient and only 11.8% by a patient companion. In another study conducted in Turkey, similar to our results, 98%of the people engaging in violence toward physicians were found to be patient relatives, male, and aged 15-30years.[8]Furthermore, while studies conducted in Western countries reported that female physicians were exposed to more violence, studies in Eastern countries indicated a higher incidence of violence toward male healthcare workers.[1,4]In our study, 62.4% of male doctors were exposed to more violence. We consider this to be related to the sociocultural structure of the study area, where treats women with higher respect. Another reason may be that the number of female physicians working in the emergency service was less than that of male physicians.

Although studies report different results, most violent incidents occur in the afternoon and night shifts. In a study by Kaeser et al,[6]68% of the violent acts occurred from 02:00 p.m. to 08:00 a.m.[19]In another study, the rate of violent incidents during the night shift (11:00 p.m. to 07:00 a.m.) was 51.8%. In contrast, Ferri et al[1]found that 43% of violence occurred in the morning. In our study, we observed 49.0% of violent behavior during the 04:00 p.m. to 00:00 a.m. period. Since outpatient clinics are closed for the majority of this period, there is an increased demand for emergency services. Similarly,the smaller number of doctors, nurses, and staff working night shifts compared to daytime may cause an increase in violence. In addition, concerning the time of a year,we determined that violence mostly occurred in winter months (December, January, and February). However,we were not able to compare this finding because there were no similar studies in the literature.

The prolonged stay in the ED may also cause violence. Dawson et al[12]reported that the duration of emergency stay in cases of violence was longer than that in normal patients (median, 655.5 minutes vs. 376.0 minutes). In another study, it was found that violent incidents occurred, on average, at the 109thminute of the patients’ presentation to the emergency service, and the mean duration of stay in the emergency service was 302.5 minutes.[16]In our study, 60.5% of violence occurred in the first 15 minutes of emergency presentation, and the average waiting time of our cases in the emergency service was 98.7 minutes. When compared to the literature, the duration of stay in our ED was shorter. This may be due to the fact that our ED provides services to all patients with an open door policy.There are a high number of non-urgent cases that receive basic care such as prescriptions that should be seen in outpatient clinics. We need to specify that the triage has been performed by a nurse in our ED, but no patients are returned by a triage nurse without a doctor examination because of the health policy. The emergency physicians do not oppose this situation and examine all patients to avoid legal transactions.

Mirza et al[4]showed that from the perspective of physicians, a lower level of education (52.5%) and higher social status (41.0%) are factors that might lead to violence. In a study comparing migrants of low-income and high-income countries, it was found that the former had a higher tendency to violence.[6]However, in the current study, unlike the literature, violence was mostly caused by individuals living in urban areas and having middle-upper income levels (covered by SSI insurance).

Limitations

The main limitation of our study was the exclusion of violent incidents involving emergency service employees other than emergency physicians (e.g., nurses,technicians, and security guards). In our experience,the number of violent acts against these staff is actually higher than that of physicians. However, most of these incidents are not reported, and therefore we did not have access to this information and we had to limit our data to emergency physicians.

CONCLUSIONS

More than half of the violent incidents against emergency physicians occur within the first 15 minutes of presentation to the emergency service due to the dissatisfaction of the patients/patient relatives with examination or treatment and their feelings of extreme anxiety. In addition, violent behavior is mostly displayed by males and patient relatives, and during night shifts.In light of these results, our first recommendation is that the hospital management should take sufficient and deterrent measures to ensure the safety of healthcare workers. Secondly, from the moment of entry into the emergency service, regardless of the complaint,appropriate communication should be established between the patients and the physicians, and the patients should be adequately informed about the treatments and interventions to be performed in order to prevent possible acts of violence. Furthermore, problems related to the infrastructure of hospitals, such as the shortage of physicians and other healthcare personnel, should be resolved by the management. For other frequently encountered problems, such as patient requests for unnecessary medical reports, informatory signs explaining that such unethical requests are not granted should be clearly displayed in various parts of the emergency service.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We thank Associate Professor Behice H. Almıs(Psychiatry), Associate Professor Ugur Lök (Emergency Service), and Associate Professor Umut Gülactı (Emergency Service) for their contribution to the interpretation of the participants’ responses.

Funding:This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval:This study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Adiyaman University (Approval number: 2018/8-9).

Conf licts of interests:We have read and understood the journal’s and ICJME policy on declaration of interests and declare that we have no competing interests.

Contributors:KT and EY offered the idea and conducted the literature review. KT, MKY, and MKP collected the data together.KT and EY performed the statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. MKP and MKY participated in the interpretation of the data and critically reviewed the manuscript.

World journal of emergency medicine2021年2期

World journal of emergency medicine2021年2期

- World journal of emergency medicine的其它文章

- Does shifting to professional emergency department staffing affect the decision for chest radiography?

- Effectiveness of an educational program on improving healthcare providers’ knowledge of acute stroke: A randomized block design study

- Role of urine studies in asymptomatic febrile neutropenic patients presenting to the emergency department

- Poor outcomes of delirium in the intensive care units are amplif ied by increasing age: A retrospective cohort study

- Efficacy and safety of corticosteroids in immunocompetent patients with septic shock

- Blood eosinophils and mortality in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: A propensity score matching analysis