威尼斯双年展:给未卜的明天设立的开放实验室

卢卡·莫利纳里/Luca Molinari

庞凌波 译/Translated by PANG Lingbo

“我们需要一个新的空间契约。”

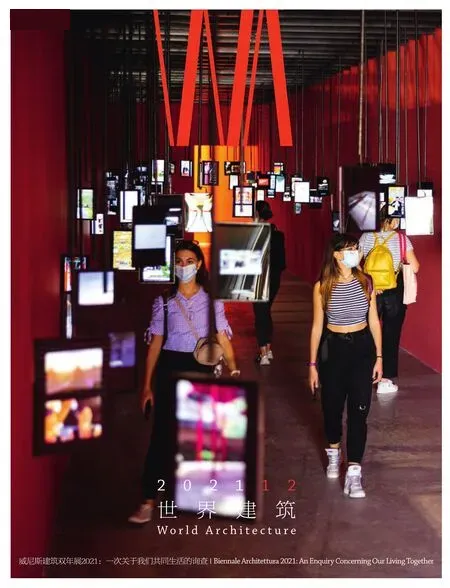

这是第17届威尼斯建筑双年展策展人哈希姆·萨基斯在第一次新闻发布会上的开场白,几个月之后,我们就被新冠疫情的洪流淹没。而这次展览不知不觉成为这一剧变世界中一个必要的实验场。

出于这样的原因,此次精心筹备的公共事件,在国际层面上,承担着第一次公开活动的重要责任,在经历了近两年戏剧性的桎梏之后,对其进行批判并不容易。

萨基斯确定的主题一经提出便带上了预言色彩,在不断崛起的反城市思想的压力下,几个月的封锁期内,许多专家和评论员的文章为我们城市的未来命运敲响了丧钟。

到现在,第三波疫情已经过去,历史上最大规模的疫苗运动已然开启,对大都市命运的悲观反思似乎迅速退却,而“我们如何共同生活?”这个主题对于我们要如何想象未来几十年的居所仍具有紧迫性。

另一方面,由策展人发起的问题和对新一代参展人的大规模号召,动摇了双年展令人信服的传统模式。多年来,双年展一直非常注重策展人与其诠释者之间的关系,以及对当代建筑艺术现状令人欣慰的描述。

5个主题组成的展览结构,以一种从宏观到微观的方式进行组织。大多数作品和装置因其脆弱性和问题性而吸引人,并且与前几届双年展许多更严谨的选择相比似乎截然不同。

2021年的双年展代表了两个渐行渐远的世界之间真实的结构性裂缝,这两个世界在新冠疫情之前与之后存在着显著的分离峰值,也在由策展人陈述的展览理念和作为一个开放实验室的展览愿景之间存在巨大鸿沟。

萨基斯策划的展览并不具备保罗·波托格西的“新大道”或是福克萨斯的“少一些美学,多一些伦理”那样标志性的力量,但是,它巧妙地引入了对重大事件所必须具有的新方向的怀疑和不确定——成为一个问题导向的、集体的、开放的实验室,在其中,建筑需要为之提供可能的答案,来对经历着划时代意义蜕变的世界做出反应。

在这样的条件下,与形式及其在形成我们居所的过程中所扮演的角色的对峙不可避免,也许在这方面,今年的双年展尤其薄弱,就好像各展览已经集体放弃了令人心安却无力回应总策展人提出的问题的标志性元素。

在这些反映这个不确定时代的方案中,不完美和不确定性普遍存在,它们在被动收集可阅读的数据(仿佛这是一种神奇的会导向结果的占卜活动)和笨拙追求艺术实践来回答这些共性问题之间不安地交替着。

在展出的许多作品中存在着对形式的不信任,几乎是对所谓“明星建筑师”的短暂历史时期的一种代际反应,在那个时期,个人研究造成了短期内全球范围孤芳自赏的形式主义的普遍状况,非但没有推动当代建筑文化的进步,反而将其禁锢在一个到处都是消费主义的快餐式作品的无限集合中。

2016年由亚历杭德罗·阿拉维纳策划的双年展已经提出了这一问题,以一种专注而激进的方式看待“南半球”,在那里,建筑在空间干预中承担着政治责任,并通过自身与当今世界中苦难和待解决矛盾之间的关系来评价自己。

但我们有必要更进一步,而且新冠疫情近乎悖论地提供了一个塑造威尼斯双年展的机会,这是一个回应这个不稳定时代的不完美尝试。在这个对我们的生活如此重要的问题——最终重新制定一个既是社会也是空间的契约的必要性背后,隐藏着一个戏剧性的问题:在急剧变化的世界里,建筑可以发挥什么作用?

由萨基斯提出的主题,不仅对世界提出了一个开放性问题,而且,对他所代表的人群,也就是建筑文化和职业世界所发起了挑衅。在发达国家明确收紧新建筑建设以减少土地和资源消耗的情况下,设计师将扮演什么角色?另一方面,建筑师可以为快速发展的国家提供什么模式?

在全球气候与环境危机日益严重的情况下,鉴于建筑是产生温室气体排放的重要部分,它能够做出怎样的贡献?面对生物章程修订中恢复人类中心地位、使其与其他生物处于同一开放循环体系的趋势,我们居住环境的设计可以产生怎样的影响?

面对新生代压力下正在迅速转型的社会、种族、性别状况,为更加动荡不安的社会主体做空间想象意味着什么?

除了所有这些问题,还有政治思想和行动的愈发软弱模糊,使得近年来不断出现孱弱的政府,愤怒和无知的民粹主义,以及慷慨愿景的匮乏,这些都无法为建筑思想提供养分和机遇。

我们生活在一个普遍短视的时代里,在由咄咄逼人的超资本主义驱动的永恒当下,长期的愿景和个人的批判性思维已不再是追求。

这个无尽的当下建立在对历史的遗忘上,同时也建立在对乌托邦幻想的放弃上——它是西方文化自文艺复兴至今唯一正确的概念和感觉引擎。因此,能够产生远见卓识并带来行动的乌托邦理念的匮乏,与本次双年展所激发的问题形成了一种强烈的概念对比,而本次双年展则试图在认识论和期望的勇敢转变的基础上严肃发问。

也许这就是为什么年轻且有意愿的参展人们的回应无法真正满足我们的期待。但这也是为什么本届威尼斯双年展正在成为国际建筑展史上参观人数最多的活动,年轻观众的比重尤其出乎意料。

这可以被简单视为一种后疫情效应吗?还是说,这是一次在大危机时代中提出了正确问题的展览?

我相信,由哈希姆·萨基斯策划的威尼斯双年展最终鼓起了勇气来面对我们正在经历的矛盾的现实,以及由新一代的年轻公民们坚持提出的新的意义问题。

换句话说,我们在未来的几十年想要居住和建造一个怎样的世界?为了应对历史上绝无仅有的环境和意义危机,我们必须设想怎样的新的、空间和生活之间的契约?

在选择主题展参展设计师的过程中,萨基斯已经正式申明,我们让在1990年代末和21世纪前20年从业和有所成就的建筑师提供他们的作品所不能提供的答案。

这并非势利的选择,也不是对智力的挑衅,而是考虑到现状需要一种观念上的转变,唯有新一代年轻人才能用他们可能拥有的不完美的直率的工具来提出构想。

也许这一选择真正的局限性在于出发点,即寻找的参展人仅限于那些来自发达国家杰出学校的年轻人,事实上他们是经由设计和文化工具训练出来的青年精英,而这些工具尚未针对新世界重新制定。尽管有一系列参展人呼吁,非洲仍然被排除在选择之外,东欧艰难地博得一席之地,南美则止步于已经成熟且趋于稳定的公民建筑,东南亚成为有待调查的多样性实验室,而意大利在享有几十年的文化中心地位之后,成为了最重要的缺席者之一。

除了对地理的反思,在本世纪,景观的项目概念已经获得了社会和意义上的优先地位——即使这方面尚未得到深入研究。这样做的目的在于将注意力从以人类中心主义的项目概念转移到与景观更相关的概念,它可能成为生态再循环的愿景的关键。

由于新冠疫情和有限的工作周期,双年展未能成为它未来几年应当成为的当代性实验室,或是对一部分新概念的制定进行再思考,这些都属于大型展览的作用,但应当补充实验和研究的维度,对展览本身进行预期,成为批判意识的发动机。

我们不再需要展览去展示那些可以在网上立刻找到的作品和项目,今天,我们比以往任何时候都更需要开放的公共实验室来生产创新和勇敢的批判性内容,它能够转移一个学科疲软的重心,使其必定随着它们被要求改造的世界而变化。

然而,这不应当在通常令人熟悉的具有诱人颜色和形状的数据、表格和图表中解决,而应当在产品中解决,其中,革命性设计理念必然带着再生和公认的政治与社会责任回归中心。我们并不认为这一宏伟问题仅是针对建筑提出的。神化建筑师的时代——凭借其项目的破坏性和救世主的力量将世界扛在肩上的“阿特拉斯”的时代——已经过去了,而我们将越来越需要慷慨而有远见之人,需要能够与其他学科在同一系统中工作之人,需要能够意识到建筑思想将产生必要形式,并且有能力协调并结合不同知识共同对话之人。

“我们如何共同生活?”将在很长一段时间内成为一个必须给出答案的紧迫问题,这使得2021年的威尼斯双年展成为持续反思的有益时机。

"We need a new space contract." This was the phrase that opened the first press conference of Hashim Sarkis, curator of the 17th International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale, a few months before we were overwhelmed by the pandemic and this exhibition unwittingly became a necessary laboratory in a rapidly changing world.

For this reason, it is not easy to comment critically on an event that has had such an exceptional gestation and that has taken on the responsibility of being the first major public and open moment at international level, after almost two years of dramatic confinement.

The title chosen by Sarkis was immediately charged with a prophetic sense, under the pressure of a rising anti-urban thinking that in the months of the lockdown seemed to run through the texts of many experts and commentators ringing death knell for the future fate of our cities.

Now that the third wave is over and the most massive vaccination campaign in history has begun, it seems that the most pessimistic reflections on the fate of our metropolises have immediately receded, while the title "How will we live together?" remains in its urgency with respect to how we want to imagine the places we will inhabit in the coming decades.

The question launched by its curator and the massive call for a new generation of authors to propose visions, on the other hand, has had a destabilising effect on the traditional, reassuring formula of the Biennale, which for some years had focused heavily on the relationship between the curator-demostrator and an often reassuring account of the state of the art in contemporary architecture.

The structure in five thematic sections, organised in a scalar fashion from the infinitely large to the microscopic, produced works and installations that proved interesting in most cases because of their fragility and problematic nature, and seemed to clash violently with many of the more disciplined choices of previous Biennales.

The 17th Biennale represents a real structural fissure between two worlds that could be increasingly distant from each other and that have had in the pandemic a violent peak of separation between a before and an after, between the idea of the exhibition as an authorial statement and the vision of the exhibition as an open laboratory.

The exhibition curated by Sarkis does not have the iconic power of Paolo Portoghesi's Strada Novissima or Fuksas's "Less Aesthetics More Ethics", but, if anything, subtly introduces the doubt and instability of a new and necessary direction to which major events are called, namely that of being a problematic, collective and open laboratory for responding to a world experiencing an epochal metamorphosis of meaning to which architecture is called upon to provide some possible answers.

This condition must not be exempt from a confrontation with form and its role in giving substance to the places we inhabit, and perhaps in this, this year's Biennale exhibition is particularly weak, as if it had collectively given up on identifying reassuring iconic elements that are incapable of looking at the problems posed by the curator.

There is a sense of imperfection and instability in the proposals that reflect this uncertain time, in a restless alternation between the compulsive collection of data to read, as if it were a haruspex activity that will then magically lead to the project, and the clumsy attempt to pursue artistic practice to answer such broad questions.

In many of the works on show there is a sort of distrust of form, almost a generational reaction to the brief historical period of the socalled "archistars", in which individual research has produced, in a compressed period of time, a widespread condition of narcissistic formalism on the scale of the global market, which has not advanced contemporary architectural culture but frozen it in an infinite collection of ready-to-wear works easy to consume in every corner of the world.

The 2016 Biennale curated by Alejandro Aravena had already posed the question, looking in an attentive and militant manner at all those "souths" of the planet in which architecture had taken on the political responsibility of intervening, measuring itself against the painful and unresolved contradictions of the present world.

But there was a need to move forward, and the pandemic has paradoxically provided an opportunity to shape an edition of the Venice Biennale that is an imperfect attempt to respond to this unstable time. Behind this question that is so central to our lives and the need to finally reformulate a pact that is both social and spatial, lies the dramatic question of what role architecture can play in a world that is changing so rapidly.

The theme posed by Sarkis is not only an open question to the world, but above all a provocation launched at the category he represents, i.e. architectural culture and the world of the profession. In a perspective of clear contraction of new construction in advanced countries to reduce consumption of land and resources, what role will the designer play? On the other hand, what models can architecture offer in rapidly expanding countries?

In the midst of a mounting global climate and environmental crisis, what contribution can architecture make, given that it is responsible for a significant part of greenhouse gas emissions? In the face of a revision of biological statutes that will tend to restore the centrality of the human being to an open and circular dimension with all other living beings, what impact can the design of the environments we inhabit have?

In the face of a social, racial and gender condition that is undergoing a rapid transformation under the pressure of new generations, what does it mean to imagine spaces for an increasingly fluid and restless social body?

To all these questions we add an increasingly weak and ambiguous role of political thought and action that in recent years is producing weak leadership, angry and ignorant populism, and an absence of generous vision that cannot be nourishment and opportunity for architectural thought.

We are living in a time of widespread myopia crushed on an eternal present driven by an aggressive hyper-capitalism that does not ask for long-term visions and individual critical thinking.

An infinite present that works on the amnesia of our histories and, at the same time, on the cancellation of utopian thought, the only true conceptual and sense engine of Western culture from the Renaissance to today. The lack of a utopian tension capable of producing visionary thoughts and actions thus enters into a radical conceptual contrast with the questions generated by this Biennale, which instead seeks to pose serious questions that presuppose a courageous epistemological and prospective shift.

Perhaps this is also why the responses offered by such young and willing authors could not formally live up to our expectations? But is it also for this reason that this Venetian edition is becoming the most visited event in the history of International Architecture Exhibitions with an unexpected percentage of young people?

A simple post-pandemic effect or, instead, an exhibition that asks the right questions at a time of widespread crisis?

I believe that the Biennale curated by Hashim Sarkis has taken the courage to finally face up to the contradictory realities we are experiencing and the emerging questions of meaning that a new generation of young citizens is insistently asking.

In other words, what kind of world do we want to inhabit and build in the coming decades? What new social, spatial and inter-living pact must we imagine in order to respond to an environmental and symbolic crisis that has no parallel in our history?

In selecting the invited designers, it is as if Sarkis has made it official that we cannot ask the generation of architects who established themselves between the end of the 1990s and the first two decades of the new century to provide answers that their work has not been able to provide.

This is not a snobbish choice or an intellectual provocation, but the consideration that the current situation requires a conceptual shift that only a different generation can begin to formulate with the imperfect and blunt tools that these authors may have.

Perhaps the real limitation of this selection is the starting point, namely the fact that the search for authors has been limited to young people from the great universities of the advanced world, in fact a young elite that has been trained with design and cultural tools that have not yet been reformulated with respect to a new world. Africa is still missing from this selection, despite the call of a series of quality authors, Eastern Europe emerges with difficulty, South America stops at the architecture of civic action that is now a mature and consolidated practice, the countries of South-East Asia that are now a laboratory of diversity to be investigated and, in its own small way, Italy, one of the great absentees after decades of cultural centrality.

In addition to these geographical reflections, due attention has not yet been paid to the landscape project and the social and symbolic centrality it is acquiring in the overall revision of the concept of the project in this new century, perhaps because the very idea of landscape could be an important basis in the reinterpretation of a circular and less anthropocentric vision of the very notion of the project.

Due to the pandemic and the usual compressed timeframe, the Biennale has not been able to be that laboratory of contemporaneity that it should be in the coming years, rethinking even part of the formula, which clearly cannot do without the large exhibition, but should expand an experimental and research dimension that anticipates the exhibition itself, becoming a motor of critical sense.

What we no longer need are exhibitions that tell us about works and projects that we immediately find on the web, while today, more than ever, we need open public laboratories that produce innovative and courageous critical content, capable of shifting the tired centre of gravity of a discipline that must change with the world it is called upon to transform.

This, however, should not be resolved in the usual reassuring collection of data, tables and infographics in seductive colours and shapes, but in products in which the reformed idea of design must return to the centre with a regenerated and recognised sense of political and social responsibility. Together, we cannot think that questions of this magnitude are posed only to architecture. The time of the demiurge architect, of the Atlas who holds the world on his shoulders thanks to the disruptive and messianic force of his projects, is over, while we will increasingly need new generous visionaries capable of working in a system with other disciplines, aware that architectural thought produces necessary forms and, at the same time, has the capacity to coordinate and bind different knowledge that can dialogue together.

"How will we live together?" will remain for a long time an urgent question to which different answers must be given, and this makes the 17th Biennale a useful occasion to continue reflecting on.□