Evaluation of scientific evidence for abortifacient medicinal plants mentioned in traditional Persian medicine

Ensiye aafi, Malihe Tabarrai, Mehran Mirabzadeh Ardakani, Mohammad Reza Shams Ardakani,3, Seyede Nargess Sadati Lamardi*

Evaluation of scientific evidence for abortifacient medicinal plants mentioned in traditional Persian medicine

Ensiye aafi1, Malihe Tabarrai2, Mehran Mirabzadeh Ardakani1, Mohammad Reza Shams Ardakani1,3, Seyede Nargess Sadati Lamardi1*

1Department of Traditional Pharmacy, School of Persian Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.2Department of Persian Medicine, School of Persian Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.3Department of Pharmacognosy, Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences Research Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Miscarriage or spontaneous ending to a pregnancy takes place at the early stages of pregnancy without intervention. Pregnant women may use medicinal herbs to relieve some of the symptoms of pregnancy as they believe that all herbs are safe. Some abortion-inducing herbs were mentioned by the famous Iranian philosophers, Avicenna and Aghili, in documents of traditional Persian medicine titled Al-Qanun Fi Al-Tibb(, written by Avicenna in the 11thcentury) and Makhzan Al-adviyah(, written by Aghili in the18thcentury).Electronic databases such as PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, Cochrane Library and Web of Science were searched to find new scientific evidence that these plants are toxic during pregnancy. Data was collected from 1831 to 2019.Twenty-one plants were found to be abortive according to Al-Qanun Fi Al-Tibb () and Makhzan Al-adviyah(). Scientific research has shown that these plants possess abortifacient effects by the mechanisms of toxic alkaloids, uterine stimulants, and emmenagogue that interferes with implantation and results in fetus toxicity. These studies included in vivo or in vitro studies. Some of these plants showed abortifacient effects by more than one mechanism.,,,,,,andpossess uterine stimulant properties.,,,,,andinterfere with implantation.,,,,,,,, andexhibit emmenagogue effects.,,,,,andcontain toxic alkaloids and possess teratogenic effects.The results of this study of traditional Persian medicine resources have been confirmed with new scientific evidence. Therefore, pregnant women should avoid consuming herbs without knowledge of their safety.

Miscarriage, Medicinal plants, Traditional Persian medicine, Abortifacient

This review provides new scientific evidence for abortifacient medicinal plants mentioned in traditional Persian medicine and discloses their underlying abortifacient mechanisms.

The first ancient Persian document that mentions abortifacient herbal drugs is the Avestathe holy book of, in 600 B.C., which mentions some abortifacient drugs such as(gold, a yellow liquid or some type of plant) and(a deadly medicine)Subsequently, Al-Qanun Fi Al-Tibb(), one of the most comprehensive pharmacopeias in the field of medicine written by Avicenna in the 11thcentury, and Makhzan Al-adviyah()one of the largest pharmacopeias of traditional Persian medicinewritten by Aghili in the18thcentury, record additional abortifacient properties for some herbal drugs, such asand

Background

Miscarriage or spontaneous pregnancy loss occurs before 24 weeks of gestation with no intervention [1,2]. Nearly 15% of all pregnancies terminate spontaneously [3]. The etiology of miscarriage is related to maternal and fetal parameters [4]. Approximately 65–80% of the world’s population use traditional medicine for health care. There is insufficient data concerning pregnant women who use herbal medicines during pregnancy, however their numbers are on the rise [5]. Epidemiological studies have shown that the consumption of herbal medicines by pregnant women ranges from 27–57% in Europe and 10–73% in the US [6]. Several studies found that women use herbal medicines more often than men [7]. Herbal medicines used by the general population are usually safe. However, there is limited information regarding the safety of herbal medicines during pregnancy [5, 8].

Herbal medicines have played a significant role in the prevention and treatment of diseases for millennia. There are more than 35,000 medicinal species of plants and many people in world use these herbal drugs [9, 10]. Some herbal medicines possess contraceptive, abortifacient, uterinestimulant, and estrogenic effects in animals and humans [11]. Pregnant and nursing mothers must be cautious about the use of herbal drugs during pregnancy and lactation. Certain herbal drugs are unsafe in pregnancy as they can cross the placental barrier and can induce abortion by uterine contractions. They can also result in birth defects and death [12, 13]. Consumption of herbal drugs by pregnant women varies in different regions and cultures. Women use herbal medicines to treat some symptoms caused by pregnancy such as nausea, vomiting, constipation, anxiety, etc. [14]. During pregnancy, women are concerned about the side effects of herbal and/or chemical drugs [15, 16].

During the first trimester of pregnancy, some active ingredients can cross the placental barrier and harm the fetus due to their toxic, teratogenic, and abortifacient effects [17]. Consumption of some herbal drugs in this period can result in complications [18]. Herbal drugs induce abortion by different mechanisms like stimulation of menstruation and their alkaloid, essential oil, and anthraquinone content, their laxative properties, and their effects on the hormonal system [12].

Persian medicine is a type of complementary and alternative medicine adopted from Indian, Egyptian, and Greek medicine along with their examinations. The first ancient Persian document that mentions abortifacient herbal drugs is the Avestathe holy book of, in 600 B.C. which mentions some abortifacient drugs such as(gold, a yellow liquid or some type of plant)and(a deadly medicine)Subsequently, Al-Qanun Fi Al-Tibb(), one of the most comprehensive pharmacopeias in the field of medicine written by Avicenna in the 11thcentury and Makhzan Al-adviyah()one of the largest pharmacopeias of traditional Persian medicine (TPM) written by Aghili in the18thcentury, records additional abortifacient properties of some herbal drugs, such asand

The aim of this study is to warn pregnant women regarding the use of potentially harmful herbal medicines and discuss their safety during pregnancy. Selected plants with abortifacient effects were collected from traditional medicine sources and their effects were evaluated and provided in modern medical terms.

Methods

Search strategy

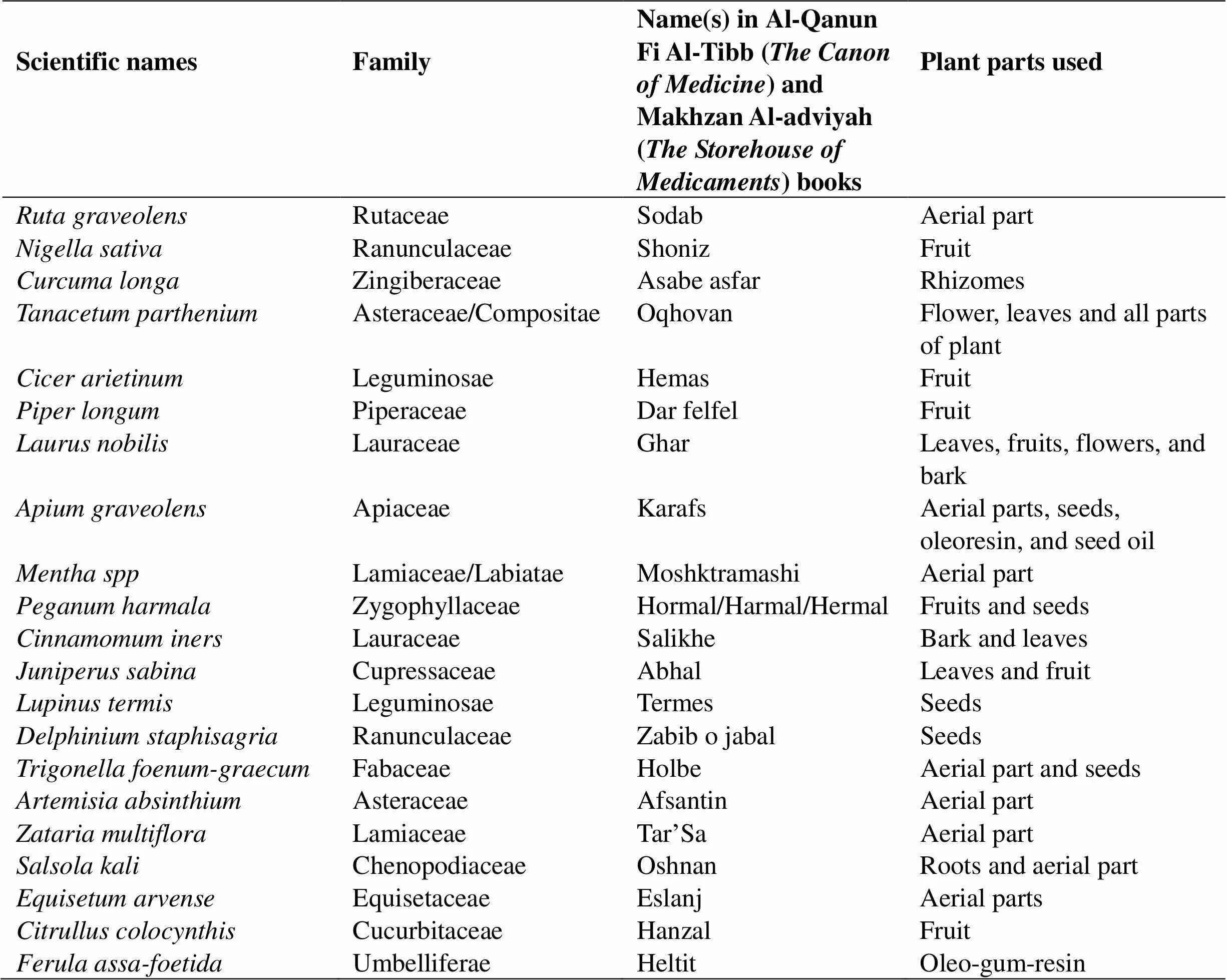

In this review article, medicinal herbs inducing abortion were collected from traditional literatures including Al-Qanun Fi Al-Tibb() and Makhzan Al-adviyah()(Table 1)[19, 20]. The abortifacient effect of the herb was researched using the terms(abortion)(abortion), and(expulsion of the fetus). The name of each plant was extracted and matched using the reference book titledwritten by AG. Ghahreman and AR. Okhovvat.

Then, appropriate keywords were extracted from mesh. A pilot search was completed in PubMed to discover additional key words such as abortion, abortive, abortifacient, fetus, uterus, uterine, emmenagogue and their equivalents with the combined form of these terms and with no language restrictions. The search strategy was performed in Google Scholar, PubMed, Science Direct, Scopus and Web of Science databases for each plant. After detecting keywords and their equivalents, the search strategy was determined.

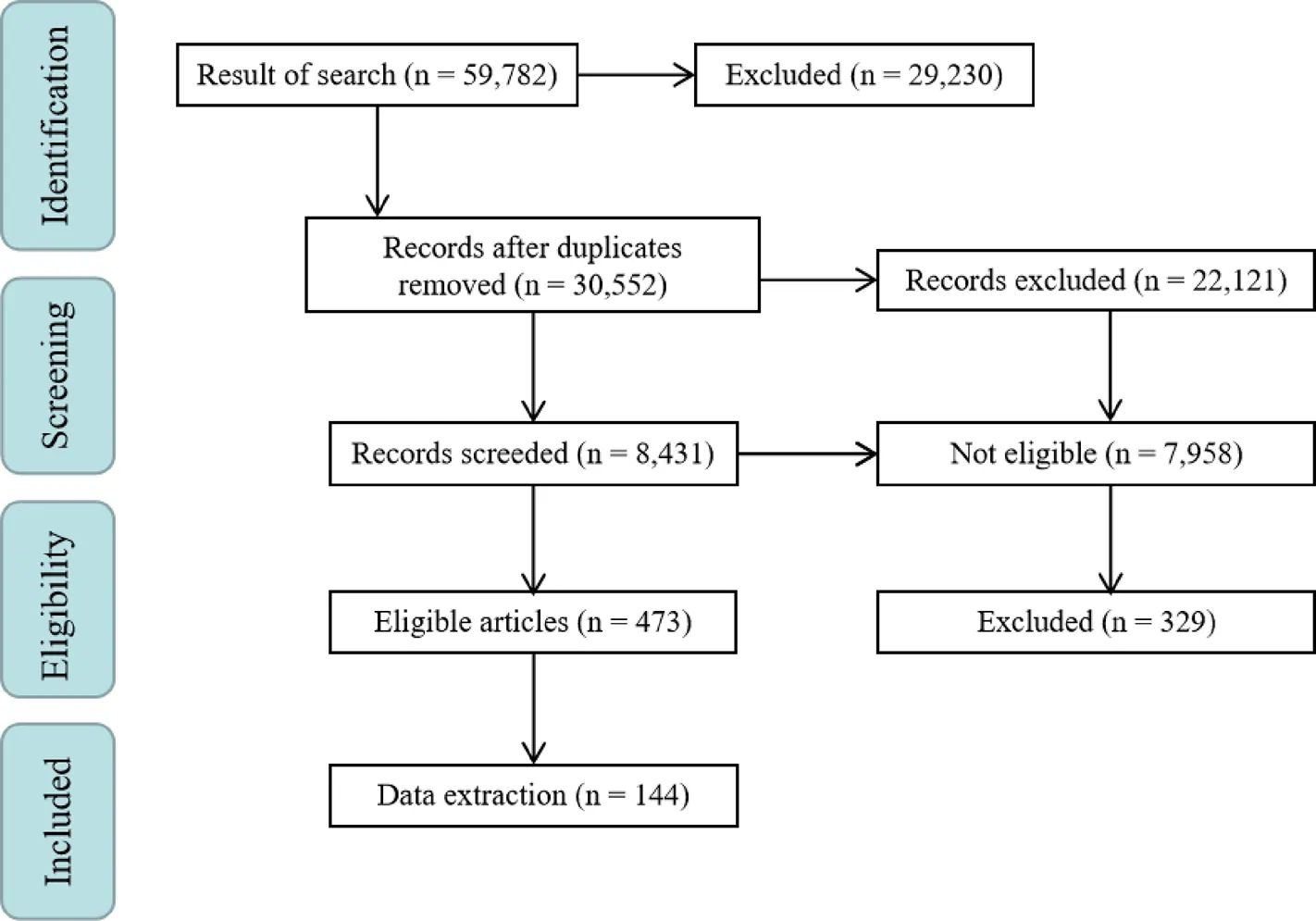

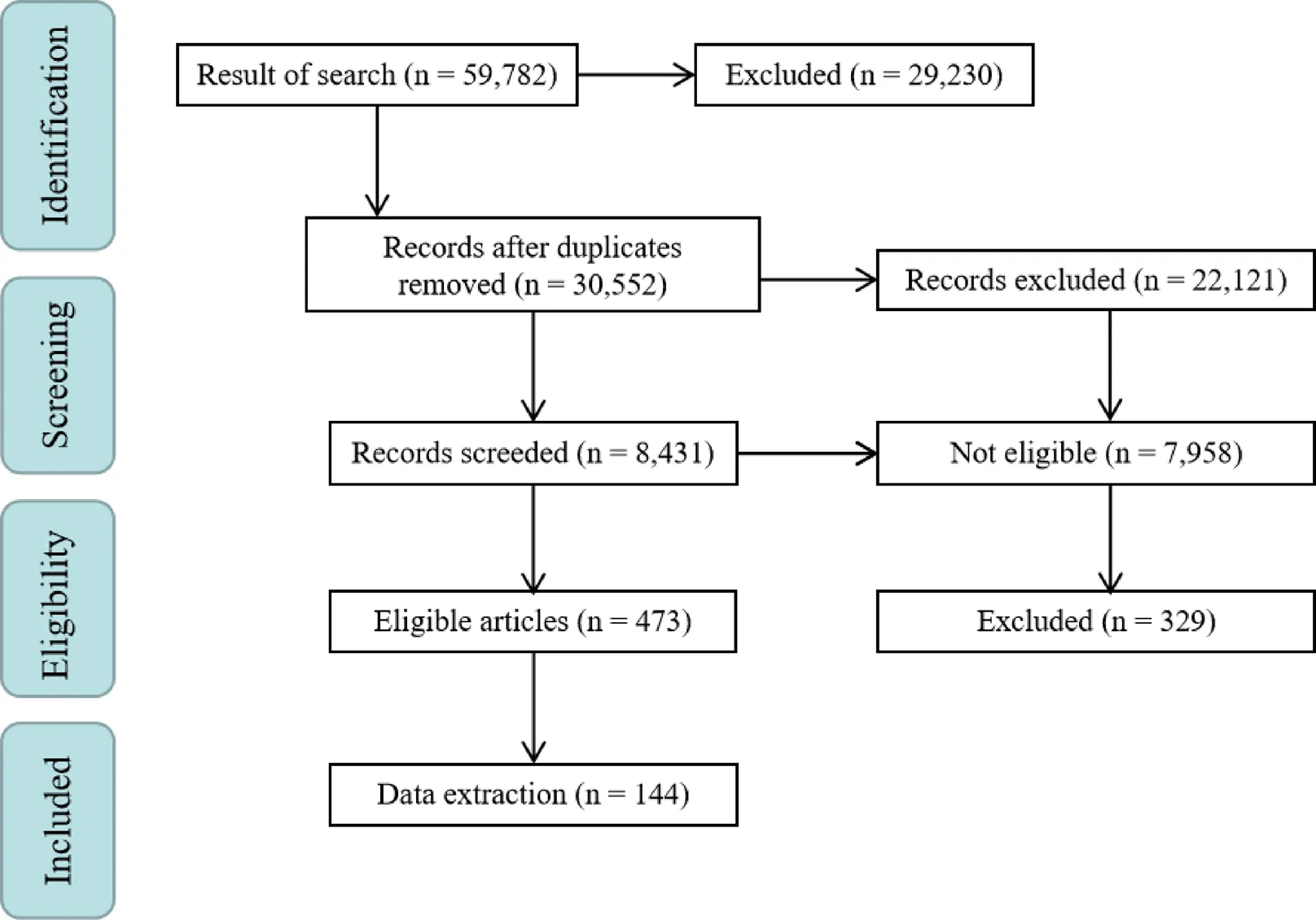

Paper selection

To increase precision, the articles were evaluated by 2 members of the research team separately. For this step, 2 members of the team acted as leads to evaluate the articles. First, duplicated articles were omitted, and invalid documents were selected from none-reliable sources such as newspapers, lectures, posters etc. as they were unable to demonstrate validity of the research. Subsequently, the full text of the articles was obtained by the Central Library of Tehran University of Medical Sciences. For inaccessible articles, emails were sent to the corresponding authors. Valid documents were classified by subject. Findings for each herb were evaluated in vitro and in vivo to investigate the pharmacologic mechanism of the abortifacient effect. The evaluations were sorted into in vitroorin vivostudies and a brief mechanism of action of each plant was stated. Ultimately, the text of the article was written (Figure 1). To manage the articles, EndNote Ver.X7 was used.

Data extraction

After the articles were validated, their referenceswere collected separately. Each of their findings were evaluated and the related articles were selected. The citations of these articles were researched. Finally, selected articles and their citations were used in this article.In this study, 144 articles were discovered and 117 of them were related to the results section.

Results

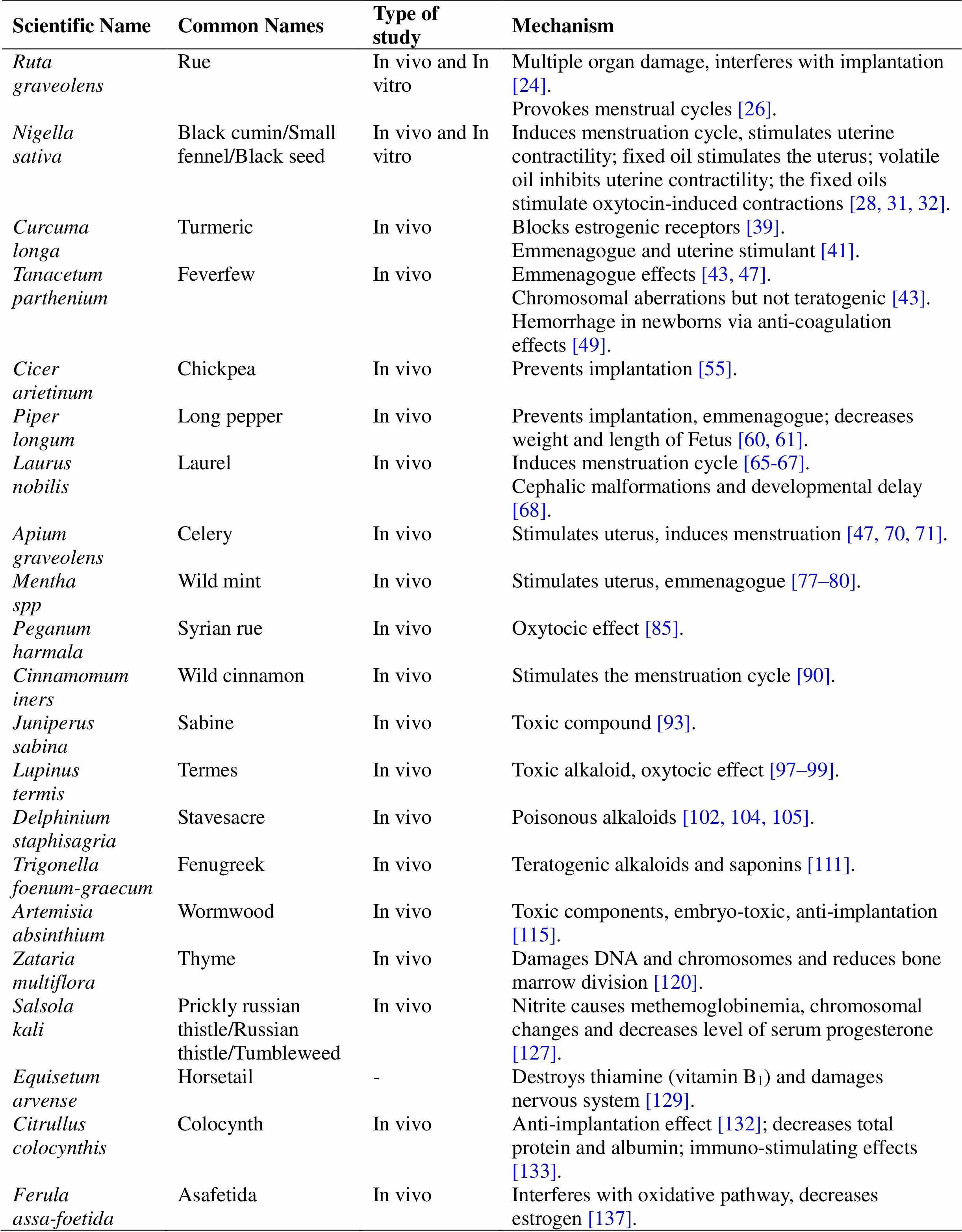

Twenty-one abortifacient plants are mentioned in Al-Qanun Fi Al-Tibb() and Makhzan Al-adviyah(). The evidence supporting their abortive effects are presented in the following text. Abortion occurs in some women recurrently. Specific plants have untoward effects as a side-effect when used in large amounts. Abortifacient plants are often consumed as herbal drugs and the number of documents that were found for each plant are as follows:6,10,3,5,8,7,7,7,3,5,5,7,5,9,4,3,4,5,5,4, and5 (Table 2).

Table 1 Herbal medicines mentioned in Al-Qanun Fi Al-Tibb(The Canon of Medicine) and Makhzan Al-adviyah(The Storehouse of Medicaments) with abortifacient effects

Figure 1 Article flow chart

Abortifacient effects due to stimulation of the uterus and/or emmenagogue

.which belongs to the Rutaceae family is an ever-green shrub distributed around the world [21]. All the aerial parts ofare used [22]. In TPM, numerous properties have been implied for its use, such as an anti-inflammatory, an analgesia, a carminative and an anti-helminthic [20]. Some of its chemical constituents are glycosides (rutine, a flavonoid) and alkaloids (quinolones: coquisagenine, skimmianine, and graveoline) [23]. Dried aerial parts ofinduce abortion through the mechanism of multiple organ damage and death. There is no estrogenic effect, however it can interfere with implantation time [24]. The aqueous extract interferes the pre-implantation phase in mice [25]. Moreover,stimulates the uterus and results in menstrual cycles [26].

., commonly known as black cumin, black seed or small fennel, is an annual plant of the Ranunculaceae family endemic to southwest Asia [27]. In TPM it is believed to have anti-helminthic and diuretic properties and to be used in respiratory disorders.It is also used for cough, kidney stones, hair loss, insect infestations, to increase milk production, and as an anti-headache medication [20]. The chemical constituents ofare carbohydrates and oils. The lipid profile ofis composed of essential oils and fixed oils. The fixed oils contain triglycerides and sterols.

also contains carotene that is converted to vitamin A. Other vitamins include thiamine, riboflavin, pyridoxine, folic acid, and niacin. The mineral content ofincludes K, Ca, phosphorus, Fe, Cu and Zn. Isoquinoline and pyrazole are 2 coumarins that are found in its seeds.Other components are lectins, saponines, tannins, resins, and flavonoids [28–30].can cause abortion by inducing menstruation cycles. The fixed oils of black cumin can stimulate uterine contractility both in vitro and in vivo, while the volatile oils inhibit the contractility of uterine smooth muscle of pigs and rats induced by oxytocin. The fixed oils cause abortion by stimulating oxytocin-induced contractions in pregnant rats. This different effect may be due to various animal species and dosage forms [28, 31, 32]. Thymoquinone is the main constituent of the essential oil of[33]. Thymoquinone possesses spasmolytic effects by the means of blocking Ca2+channels, it inhibits the automatic movement of the uterine smooth muscle in guinea pigs and rats and has anti-oxytocic effects [34]. The methanol and acetate seed extract ofpossess significant abortifacient effects at a dose of 2 gr/kg body weight for 3 days on days 14–16 after intercourse in pregnant rats [35]. In Native Indian medicine,seeds possess emmenagogue effects at doses of 10–20 mg and high doses can induce abortion [36].

The rhizome of, turmeric, belongs to the Zingiberaceae (ginger) family, which is a perennial herb [37]. Its chemical components include curcumin, turmerone, methylcurcumin, demethoxy curcumin, bisdemethoxy curcumin, and sodium curcuminate [38].has anti-ovulation and anti-estrogenic effects via blocking estrogenic receptors and disturbing the estrogen cycle [39]. At high doses of 24 mM, curcumin decreases implantation and causes abortion in mice [40]. Turmeric possesses non-teratogenic effects in mice and rats, and non-mutagenic and non-toxic properties in rats and monkeys at high doses. Its rhizome has potential abortifacient, emmenagogue, and uterine stimulant effects [41].

.(feverfew), which belongs to the Compositae/Asteraceae family, is a perennial plant [42]. The flowers, leaves, and all aerial parts of the plant are used for medicinal purposes [43]. Its chemical components include terpenoids (sesquiterpene lactones) such as parthenolide, germacrene D, costunolide, estafiatin, canin (β, β-diepoxy), tanaphartolide A/B, coumarin derivatives, lipophilic flavonol, and flavonoids [44–46]. The leaves of feverfew are potentially abortifacient due to the emmenagogue effects of stimulating menstruation [43, 47, 48].Genotoxic studies demonstrated that chronic use of, although not teratogenic, could cause chromosomal aberrations and change the sister-chromatid lymphocytes of patients [43]. This plant also possesses anti-coagulation effects which can cause hemorrhage in newborns [49].

.Chickpea (), which belongs to the Fabaceae family, is widely used in Asia and Africa and is an important source of protein for humans [50, 51]. Its chemical components are proteins, amino acids, starches, short-chain fatty acids, moisture, fiber, cellulose, hemi-cellulose, lignin, B-vitamins, minerals (Na, K, Ca, Mg, Mn, Zn, Fe, Cu, P, Cr), tannins, saponins, isoflavones, and carotenoids [52–54]. The aqueous extract of chickpea shows significant abortifacient properties at 400 mg/kg and its alcoholic and chloroform extracts show abortifacient effects less than the aqueous extract. The extract contains estrogen like compounds, potentiates the effect of ethinyl estradiol, and increases the endothelial thickness. The aqueous extract of chickpea interferes with implantation by preventing mitotic cell division [55, 56].

.is a perennial herb also known as long pepper. It belongs to the Piperaceae family. Dried spikes of the fruits are used for medicinal purposes [57]. Fruits contain volatile oils, starch, lignans, protein, alkaloids (piperine, piplatin, piperlongumine, piperlonguminine), L-tyrosine, L-cysteine hydrochloride, saponins, stearic, linoleic, oleic, linolenic, carbohydrates, and amygdalin [58, 59]. Approximately 300-600 mg of the fruits or 45-90 mg of the extract is emmenagogue and abortifacient. Also, its fruit negatively affects fetal weight and length during the pregnancy [60]. The main and active component ofis piperine [57]. Its chemical composition terminates early pregnancy via the prevention of implantation by disturbing the balance of estrogen-progesterone to maintain gestation and interferes with the reproductive system [61].

., also known as laurel (Lauraceae family), is an evergreen shrub cultivated in countries with a moderate to subtropical climate in the Mediterranean region and is native to the Southern Mediterranean region [62, 63]. The leaves, flowers, and bark are used medicinally [64]. Its chemical compounds include terpenoids (sesquiterpene lactones such as 10-epigazaniolide, Gazaniolide, and spirafolide), glycosides (kaempferol-3-O-α-L- (3’,4’-di-E-p-coumaroyl)-rhamnoside), kaempferol -3-O-α-L-(2’, 4’-di-E-p-(coumaroyl)-rhamnoside), anthocyanin (major anthocyanins are cyanidin 3-O-glucoside and cyanidin 3-O-rutinoside), and essential oils (1,8-Cineole along with α-terpinyl acetate, terpinene-4-ol, α-pinene, β- pinene, p-cymene, linalool acetate) [63]. Laurel should be avoided during pregnancy as it induces menstruation cycles and results in abortion (emmenagogue) [65–67]. The aqueous extract of the leaves and flowers are tested on embryos and adult snails. The mortality rate of the flower extract is 4–5 times higher than that of the leaves extract in the blastocyst stage. Moreover, the extracts can cause cephalic malformations and developmental delay, resulting in abortion [68].

., also known as celery (Apiaceae), is an annual or biennial shrub. It is native to Africa, Asia, and Europe. Aerial parts, oleoresin, and seed oil are parts of the plant that is usually used. However, the medicinal sections are the seeds, leaves, and roots. The chemical ingredients of the various parts of the plant are different from each other [69]. The aromatic bitter tonic of celery can stimulate the uterus, induce menstruation, and cause abortion [70, 71]. Celery is not recommended for pregnant and lactating women, as it increases libido and the mensural cycle. However, there is no valid information about its abortifacient effects [72]. In one study, celery at a dose 250 mg/kg from the whole plant administered to rats on day 1–7 of implantation terminated the pregnancy [73].

The genus,which belongs to the Lamiaceae family, includes 19 spices [74]. This genus is popular around the world due its important volatile oil [75]. The volatile oils of this genus are menthol, menthone, carvone, dihydrocarvone, linalool, linalyl acetate, and pulegone. Menthol is the main volatile oil that possesses commercial benefits [76].is abortifacient due to its stimulating and emmenagogue effects [77–79]. Pulegone has abortifacient effect on the myometrial contraction by direct blocking of the voltage-dependent calcium channels [80]. The plantpossesses abortifacient effect via a similar way [81]. Pulegone is abortifacient andcontains its essential oil [82].

.(syrian rue) is a perennial plant that belongs to the Zygophyllaceae family [83].contains alkaloids, flavonoids and anthraquinones. The main alkaloids detected in theextract are harmaline, harmine, harmalol, harmol, tetrahydroharmine, vasicine, and vasicinone. The flavonoids characterized in the aerial component of this plant are l-thioformyl-8-β-D-glucopyranoside-bis-2,3-dihydro-isopyridinopyrrol, acacetin 7-O-rhamnoside, 7-O-6’-O-glucosyl-2’-O- (3’-acetylrhamnosyl) glucoside, 7-0- (2’-0-rhamnosyl-2’-O- glucosylglucoside), and glycoflavone 2’-O rhamnosyl-2’-O-glucosylcytisoside. Anthraquinones are isolated from the seeds of Syrian 8-hydroxy-7-methoxy-2-methylanthraquinone and 3,6-dihydroxy-8-methoxy-2-methylanthraquinone [84]. Its plant possesses antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, antitumor, antidiabetic, antioxidant, and cytotoxic effects [84]. An in vivo study found that the hydroalcoholic extract ofhad contractive effects on the uterus and stripped the myometrium via the external calcium flow by the voltage-dependent calcium channels [85].

(wild cinnamon) belongs to the Lauraceae family [86, 87]. Its chemical components include polyphenol, flavonoid, tannin, saponin, cardiac glycoside, stigmasterol, β-caryophyllene, terpenoid, and sugars [88]. Previous studies evaluated the analgesic, antioxidant, antimicrobial, anti-plasmodial, anticancer, cytotoxic, and inhibitory effects of glutathione-S-transferase [89]. One study investigated the abortifacient effects ofAn in vivo study found that chloroform and aqueous extracts ofcould stimulate the menstruation cycle and cause abortion in pregnant rats at a daily dose of 70 mg/kg [90].

Abortifacient effect because of a toxic compound

.(sabine), which belongs to the Cupressaceae family, is a shrub or small tree that grows in Europe, Asia, and North America [91]. The chemical composition of the leaves and fruits includes coumarin, alkaloids, tannins, and saponins. The volatile oil derivatives include sabinen, α-pinene, and myrcene [91, 92]. The major component of the essential oil, sabinyl acetate, has abortifacient effects. Sabinyl acetate can inhibit implantation in mice. A large amount of sabine can cause abortion in women in the early gestational stages due to its toxic effects [93].

. The seeds of(lupine), which belongs to the Fabaceae family, are used in traditional medicine in Africa and the Middle East. Its chemical constituents include phenolic compounds and phytoestrogens such as isoflavons and alkaloids (lupanine, lupine, sparteine) [94–96]. The abortifacient effects ofhave been demonstrated by strong stimulation and movement of the uterus in pregnant mice and rats [97]. Lupin and anagyrine are teratogenic alkaloids. One study investigatingfound that oral administration had no adverse effects on fertility of 2 generations of rats, as the rats were fed a low seed-based alkaloid. This plant possesses neurotoxicity due to lupine alkaloids, sparteine and lupanine. Acute toxicity in humans causes symptoms like malaise, nausea, respiratory arrest, visual disturbances, ataxia, progressive weakness, and coma. Its toxic alkaloid, lupin, can induce fatal effects in goats and cattle [98]. Sparteine possesses oxytocic effects and stimulates uterine contractions according to some case reports. It also causes uterine rupture through consumption of sparteine alkaloid [99]. One study found that sparteine, lupinine, trilupine, and d-lupanine dihydrochloride could contract the isolated uterus of rabbits and increase its tone or contraction rate. At the same concentration, sparteine is more contractile than lupinine; however, when the concentration increases, lupinine induces longer spasticity [100].

.,also known as stavesacre, belongs to the Ranunculaceae family.is native to Asia,Europe, and America. It contains some chemical compounds like diterpenoid alkaloids (such as isoazitine, delphinine, neoline, azitine, and dihydroatisine) [101]. Stavesacre has analgesic, antioxidant, and cytotoxic properties [102, 103]. Stavesacre contains delphinium, a poisonous alkaloid that is very toxic to humans [102, 104, 105]. Stavesacre opens the Na+channel and inhibits the neuronal transmission it also causes nausea, glycemic index and kidney discomfort, dyspnea and death from cardiac arrest. Due to its toxicity, pregnant women should avoid the consumption of stavesacre [106].

.(fenugreek) is an herbaceous plant that belongs to the Fabaceae family [107, 108]. The extracts of fenugreek contain alkaloids, cardiac glycosides, phenols, and steroids and have antibacterial, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, hepatoprotective, antioxidant, antidiabetic, antilipidemia, hypocholesterolemic, neuroprotective, and anti-carcinogenic properties [109, 110]. In vivo experiments on mice have shown that the aqueous extract of fenugreek seeds is fetotoxic and teratogenic at 500 and 1000 mg/kg. Alkaloids (trigonelline) and saponins (gitogenin) have teratogenic effects [109, 111].

.(wormwood) is a plant of the Asteraceae (Compositae) family [112, 113]. The chemical components of wormwood include flavonoids, polyphenolics, coumarins, terpenoids, sterols caffeoylquinic acids and acetylenes. This plant has antitumor, neuroprotective, hepatoprotective, anthelmintic, antimalarial, antibacterial, antipyretic, antidepressant, antiulcer, antiprotozoal and antioxidant properties [114]. Some components of wormwood possess toxic effects, including sabinyl acetate, sabinol, sabinene, and artemisia ketone. Pregnant women should avoid this plant because of its embryotoxic, abortifacient, and anti-implantation effects due to the high toxicity of sabinyl acetate [115].

.is an annual plant of the Lamiaceae family and is endemic to the Middle East, primarily Iran, Pakistan, and Afghanistan [116,117]. The chemical components ofinclude β-sitosterol, luteolin, apigenin, linalool, 6-hydroxyluteolin, thymol, carvacrol, γ-terpinene, and p-cymene [117]. The volatile oil ofpossesses its main pharmacological effect [118].has antiviral, antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-nociceptive, and immunostimulant effects [119]. High doses of some components ofincluding gamma-terpinene and thymol damage DNA. Carvacrol and thymol damage the chromosome and reduce bone marrow division in rats [120].

Other mechanism of abortifacient effects

.One of the annual halophytic plants of the Chaenopodiaceae family is, which is widely distributed in sandy areas [121–123].,also known as Russian thistle and tumbleweed, is endemic to Eurasia and North America [124]. Some of chemical components of this plant are vitamin A, phosphorus, isoqinolin alkaloids (salsolin, salsolidin), minerals (K, Ca, Mg, Al, Fe), fatty acids, kempferol, quercetine, rhamnetine, protein, and nitrate [123, 125]. Nitrate comprises 0.1–5.1% of the dry herb. The plant, with a high content of nitrate, enters the stomach wall. About 25% of the nitrate is reduced to nitrite by bacterial nitrate reductase [125, 126]. Some animal studies found that nitrate and nitrite possessed reproductive toxicity and induced abortion. One animal study showed that sodium nitrite could cross the placenta and cause methemoglobinemia in the fetus. Chromosomal changes occur at higher doses. Degenerative changes in the aborted fetus demonstrate symptomatic methemoglobinemia and tissue anoxia. There is a relationship between miscarriage and methemoglobinemia in humans. High levels can cause abortion in the first trimester of pregnancy. Chronic nitrate exposure decreases the level of serum progesterone; however, more studies are required to confirm this finding [127].

.,which is a perennial herb of the Equisetaceae family also commonly known as horsetail, is endemic to the northern hemisphere. The phytochemical content ofincludes minerals (silicic acid, silicates, K, Ca, Al, sulphur, Mg, Mn), phenolic acid (di-E-caffeoyl-menso-tartaric acid, mono-o-caffeoyl- menso-tartaric, methyl-esters of protocatechuin, caffeic acids, 5-caffeoylshikimic acid), phenolic petrosins (onitin, oniti-9-o-glucoside), flavonoids,phenolic glycosides, styrlpyrone glucosides, triterpenoides, alkaloides, saponines, dicarboxylic acids, and phytosterols [128]. Chronic consumption ofdestroys thiamine (vitamin B1) and causes deficiency in long-term use. Vitamin B1possesses neuroprotective effects and its depletion can damage the brain and nervous system causing confusion, walking difficulties, vision and eye movement problems, and memory loss. Because of its effects, this drug should be avoided during pregnancy [129].

., commonly known as colocynth, belongs to the Cucurbitaceae family [130, 131]. Ethanol and benzene extracts ofdemonstrate 60–70% anti-implantation effects in female albino rats [132].contains alkaloid and glycoside compounds and saponins, indicating that it has contraceptive activities [133]. The levels of total protein and albumin decrease during abortion andcan decrease them further and result in abortion. Moreover,possesses immunostimulating effects and induces immune attacks against the feto-placental membrane causing abortion [133].

.belongs to the Umbelliferae family and the oleo-gum-resin extracted from its root is used in traditional medicine [134, 135]. Asafoetida, the dried latex (gumoleoresin) exuded from the rhizome or tap root of, contains gum (25%), volatile oil (10–17%), and resin (40–64%). Gum fractions include glucuronic acid, rhamnose, L-arabinose, glycoproteins, polysaccharides, galactose, and glucose. The essential oil of asafetida contains monoterpenes and other terpenoids and resins including coumarins, sesquiterpene coumarins, terpenoids, ferulic acid and its’ esters. Asafetida has antifungal, anti-fertility, antiviral, antispasmodic, antiulcerogenic, digestive enzyme inhibition, anti-diabetic, antitumor, chemopreventive, molluscicidal, anti-mutagenic, and hypotensive properties [136]. The oxidative pathway is the source of energy for the pregnant uterus, and the extract ofinterferes with this pathway. In addition, it also lowers the level of estrogen [137].

Discussion

Herbal drugs used in traditional medicine possess valuable effects for many diseases and may serve as the sources of new drugs [138, 139]. Avicenna, the great Iranian physician in the 11thcentury A.D., wrote Al-Qanun Fi Al-Tibb() and introduced many medicinal plants and their pharmacological effects [19]. Seyyed Mohammad Hossein Aghili Khorasani Shirazi wrote Makhzan Al-adviyah() in the 18thcenturyA.D.andintroducedmanyherbal medicines as well [20]. In this paper, herbal medicines causing abortion and appeared in Al-Qanun Fi Al-Tibb () and Makhzan Al-adviyah () were collected and their evidence for modern medicine was evaluated.

Table 2 Studies conducted on abortifacient medicinal plants introduced in Al-Qanun Fi Al-Tibb(The Canon of Medicine) and Makhzan Al-adviyah(The Storehouse of Medicaments)

-, not mention.

These plants, through different mechanisms including emmenagogue, stimulating the uterus, preventing implantation, and teratogenic effects, act as abortifacients. Many studies discovered the abortifacient effects of these herbs in vivo and/or in vitro and confirmed the validity of the traditional documents. Studied herbal medicine revealed abortifacient effects via various mechanism. These include uterine stimulants caused by,,,,,, and. Some herbal drugs can prevent implantation such as,,,,,and.,,,,,,,, andexhibit emmenagogue effects. Some of these plants, such as,.,,,andpossess toxic derivates and cause fetal abnormalities and other complicationsOther mechanisms of action reported for abortifacient herbal medicines include anti-coagulation, methemoglobinemia, decreased levels of total protein and albumin, immunostimulation, and interferes with the oxidative pathway. Some pregnant women consume herbal medicines with no fear of abortion while some herbal drugs possess abortifacient effects at high doses, especially in high-risk women.

The essential oil of the genuslike(pulegone) [140],(bornyl acetate) [141, 142],(sabinyl acetate) [115], flavonoids of(apigenin) [143], and alkaloids of(piperine),(trigonelline) and steroidal saponins (gitogenin) [111, 144] are the main abortifacient components.

Conclusion

Therefore, TPM documents are reliable and pregnant women should avoid consumption of these toxic herbal medicines. The adverse effects of these herbal medicines may be serious and pregnant women should be cautious and avoid harmful herbal medicines.

1. Rai R, Regan L. Recurrent miscarriage. Lancet 2006, 368: 601–611.

2. Regan L, Rai R. Epidemiology and the medical causes of miscarriage. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2000, 14: 839–854.

3. Weeks A, Alia G, Blum J, et al. A randomized trial of misoprostol compared with manual vacuum aspiration for incomplete abortion. Obstet Gynecol 2005, 106: 540–547.

4. Li L, Dou L, Leung PC, et al. Chinese herbal medicines for unexplained recurrent miscarriage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016: CD010568.

5. Forster DA, Denning A, Wills G, et al. Herbal medicine use during pregnancy in a group of Australian women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2006, 6: 21.

6. Dante G, Bellei G, Neri I, et al. Herbal therapies in pregnancy: what works? Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2014, 26: 83–91.

7. Nordeng H, Havnen GC. Use of herbal drugs in pregnancy: a survey among 400 Norwegian women. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2004, 13: 371–380.

8. Wang CC, Li L, Tang LY, et al. Safety evaluation of commonly used Chinese herbal medicines during pregnancy in mice. Hum Reprod 2012, 27: 2448–2456.

9. Rajeswari J, Rani S. Medicinal plants used as abortifacients. Int J Pharm Sci Rev Res 2014, 24: 129–133.

10. Shah GM, Khan MA, Ahmad M, et al. Observations on antifertility and abortifacient herbal drugs. Afr J Biotechnol 2009, 8: 1959–1964.

11. Ashidi J, Olaosho E, Ayodele A. Ethnobotanical survey of plants used in the management of fertility and preliminary phytochemical evaluation of(L.) Moench. J Pharmacogn Phytother 2013, 5: 164–169.

12. Shinde P, Patil P, Bairagi V. Herbs in pregnancy and lactation: a review appraisal. Int J Pharm Sci Res 2012, 3: 3001–3006.

13. Newall CA, Anderson LA, Phillipson JD. Herbal Medicines: A Guide for Health-Care Professionals. London: Pharmaceutical Press, 1996.

14. Kıssal A, Güner ÜÇ, Ertürk DB. Use of herbal product among pregnant women in Turkey. Complement Ther Med 2017, 30: 54–60.

15. Westfall RE. Use of anti-emetic herbs in pregnancy: women's choices, and the question of safety and efficacy. Complement Ther Nurs Midwifery 2004, 10: 30–36.

16. Jaradat N, Adawi D. Use of herbal medicines during pregnancy in a group of Palestinian women. J Ethnopharmacol 2013, 150: 79–84.

17. de Araújo CRF, Santiago FG, Peixoto MI, et al. Use of medicinal plants with teratogenic and abortive effects by pregnant women in a city in northeastern Brazil. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet 2016, 38: 127–131.

18. Romm A. Blue Cohosh: history, science, safety, and midwife prescribing of a potentially fetotoxic herb. Yale Medicine Thesis Digital Library, 2009.

19. King C. Studies on the uterotonic alkaloids of fructus evodiae. Chinese University of Hong Kong, 1979.

20. Ibn Sina. Al-Qanun Fi Fal-Tibb (Canon of Medicine). Beiruot: Ehyaol Toras al-Arabi Press, 2010.

21. Shirazi MHAK. Makhzan ol Advieh (the storehouse of medicaments). Tehran: Tehran University of Medical Sciences, 1992.

22. Baharvand-Ahmadi B, Bahmani M, Zargaran A, et al.plant: a plant with a range of high therapeutic effect called cardiac plant. Der Pharmacia Lettre 2015, 7: 172–173.

23. Lans C, Turner N, Khan T, et al. Ethnoveterinary medicines used to treat endoparasites and stomach problems in pigs and pets in British Columbia, Canada. Vet Parasitol 2007, 148: 325–340.

24. Kováts N, Ács A, Refaey M, et al. Medical use and toxic properties of rue () and peppermint (). University of Pannonia, Institute of Environmental Engineering, 2008.

25. Tanise Gonc¸ alves de Freitas PMA, Montanari T. Effect ofL. on pregnant mice. Contraception 2005, 71: 74–77.

26. Nasirinezhad F, Khoshnevis M, Parivar K, et al. Antifertility effect of aqueous extract of airal part ofon immature female Balb/C mice.Physiol Pharmacol 2009, 13: 279–287.

27. Sharma N, Ahirwar D, Jhade D, et al. Medicinal and phamacological potential of: a review. Ethnobot Leaflets 2009, 2009: 11.

28. Assi MA, Noor MHM, Bachek NF, et al. The various effects ofon multiple body systems in human and animals. PJSRR 2016, 2:1–19.

29. Paarakh PM.Linn.—a comprehensive review. Indian J Nat Prod Resour 2010, 1: 409–429.

30. Tembhurne S, Feroz S, More B, et al. A review on therapeutic potential of(kalonji) seeds. J Med Plant Res 2014, 8: 167–177.

31. Ismail M, Yaheya M. Therapeutic role of prophetic medicine Habbat El Baraka (L.)-a review. World Appl Sci J 2009, 7: 1203–1208.

32. Aqel M, Shaheen R. Effects of the volatile oil ofseeds on the uterine smooth muscle of rat and guinea pig. J Ethnopharmacol 1996, 52: 23–26.

33. Andrade L, de Sousa D. A review on anti-inflammatory activity of monoterpenes. Molecules 2013, 18: 1227–1254.

34. Keyhanmanesh R, Gholamnezhad Z, Boskabady MH. The relaxant effect ofon smooth muscles, its possible mechanisms and clinical applications. Iran J Basic Med Sci 2014, 17: 939.

35. Velmurugan R, Jeganathan N. Post coital antifertility activity of. Asian J Org Chem 2007, 19: 4936.

36. Huchchannanavar S, Yogesh LN, Prashant SM. The black seed: a wonder seed. IJCS 2019, 7: 1320–1324.

37. Labban L. Medicinal and pharmacological properties of Turmeric (): a review. Int J Pharm Biomed Sci 2014, 5: 17–23.

38. Araujo CAC, Leon LL. Biological activities ofL. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz, 2001, 96: 723–728.

39. Sharma R, Goyal A, Bhat R. Antifertility activity of plants extracts on female reproduction: a review. Int J Pharm Biol Sci 2013, 3: 493–514.

40. Taylor G. Tumeric, National Properties, Used and Potential Benefites. New York: Nova science, 2015.

41. Mills E, Dugoua JJ, Perri D, et al. Herbal Medicines in Pregnancy and Lactation: An Evidence-Based Approach. CRC Press, 2006.

42. Fonseca JM, Rushing JW, Rajapakse NC, et al. Potential implications of medicinal plant production in controlled environments: the case of feverfew (). HortScience 2006, 41: 531–535.

43. Pareek A, Suthar M, Rathore GS, et al. Feverfew (L.): a systematic review. Pharmacogn Rev 2011, 5: 103.

44. Abad MJ, Bermejo P, Villar A. An approach to the genusL. (Compositae): phytochemical and pharmacological review. Phytother Res 1995, 9: 79–92.

45. D. Palevitch, Earon G, Carasso R. Feverfew () as a prophylactic treatment for migraine: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Phytother Res 1997, 11: 508–511.

46. Williams CA, Hoult JRS, Harborne JB, et al. A biologically active lipophilic flavonol from. Phytochemistry 1995, 38: 267–270.

47. Williams CA, Hoult JR, Harborne JB, et al. A biologically active lipophilic flavonol from. Phytochemistry 1995, 38: 267–270.

48. Ernst E. Herbal medicinal products during pregnancy: are they safe? BJOG 2002, 109: 227–235.

49. Conover EA. Herbal agents and over-the-counter medications in pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003, 17: 237–251.

50. Singh K. Chickpea (L.). Field Crops Res 1997, 53: 161–170.

51. Erle F, Ceylan F, Erdemir T, et al. Preliminary results on evaluation of chickpea,, genotypes for resistance to the pulse beetle,. J Insect Sci 2009, 9: 1–7.

52. Hughes T, Hoover R, Liu Q, et al. Composition, morphology, molecular structure, and physicochemical properties of starches from newly released chickpea (L.) cultivars grown in Canada. Food Res Int 2009, 42: 627–635.

53. Alajaji SA, El-Adawy TA. Nutritional composition of chickpea (L.) as affected by microwave cooking and other traditional cooking methods. J Food Compost Anal 2006, 19: 806–812.

54. Jukanti AK, Gaur PM, Gowda C, et al. Nutritional quality and health benefits of chickpea (L.): a review. Br J Nutr 2012, 108: S11–S26.

55. Wikhe M, Zade V, Dabadkar D, et al. Evaluation of the abortifacient and estrogenic activity ofleaves on female albino rat. J Bioinnovations 2013, 2: 105–113.

56. Singh K, Gahlot K. Pharmacognostical and pharmacological importance oflinn-a review. Res J Pharm Technol 2018, 11: 4755–4763.

57. Zaveri M, Khandhar A, Patel S, et al. Chemistry and pharmacology ofL. Int J Pharm Sci Rev Res 2010, 5: 67–76.

58. Khushbu C, Roshni S, Anar P, et al. Phytochemical and therapeutic potential ofLinn a review. IJRAP 2011, 2:157–161.

59. Manoj P, Soniya E, Banerjee N, et al. Recent studies on well-known spice,Linn. Nat Prod Radiance 2004, 3:222–227.

60. Hamiduddin AM, sofi G, Wadud A. use of traditional drugs in pregnant and nursing mothers. J Pharm Sci innov 2016, 5: 12–17.

61. D'cruz SC, Mathur PP. Effect of piperine on the epididymis of adult male rats. Asian J Androl 2005, 7: 363–368.

62. Derwich E, Benziane Z, Boukir A. Chemical composition and antibacterial activity of leaves essential oil offrom Morocco. Aust J Basic Appl Sci 2009, 3: 3818–3824.

63. Patrakar R, Mansuriya M, Patil P. Phytochemical and pharmacological review on. Int J Pharm Chem Sci 2012, 1: 595–602.

64. Al-Hussaini R, Mahasneh AM. Microbial growth and quorum sensing antagonist activities of herbal plants extracts. Molecules 2009, 14: 3425–3435.

65. Kaurinovic B, Popovic M, Vlaisavljevic S. In vitro and in vivo effects ofL. leaf extracts. Molecules 2010, 15: 3378–3390.

66. Conforti F, Statti G, Uzunov D, et al. Comparative chemical composition and antioxidant activities of wild and cultivatedL. leaves andsubsp. piperitum (Ucria) coutinho seeds. Biol Pharm Bull 2006, 29: 2056–2064.

67. Hovhannisyan D, Rukhkyan M, Vardapetyan H. Flavonoid content and in vitro antiradical activity ofleaf extracts. Agroscience 2011: 177–181.

68. Ré L, Kawano T. Effects of(Lauraceae) on Biomphalaria glabrata (Say, 1818). Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1987, 82 (4): 315–320.

69. Sowbhagya H. Chemistry, technology, and nutraceutical functions of celery (L.): an overview. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2014, 54: 389–398.

70. Fazal SS, Singla RK. Review on the pharmacognostical & pharmacological characterization ofLinn. Indo Glob J Pharm Sci 2012, 2: 36–42.

71. Tyagi S, Chirag JP, Dhruv M, et al. Medical benefits of(Celery herb). J Drug Discov Ther 2013, 1: 36–38.

72. Bazafkan MH, Hardani A, Zadeh A, et al. The effects of aqueous extract of celery leaves () on the delivery rate, sexual ratio, and litter number of the female rats. Jentashapir J Health Res 2014, 5: e23221.

73. Riddle JM. Contraception and Abortion from the Ancient World to the Renaissance. Harvard University Press, 1992.

74. Gracindo L, Grisi M, Silva D, et al. Chemical characterization of mint (spp.) germplasm at Federal District, Brazil. Res Bras PI Med 2006, 8: 5–9.

75. Singh A, Singh HB. Control of collar rot in mint (spp.) caused by Sclerotium rolfsii using biological means. Curr Sci 2004, 87: 362–366.

76. Silva D, Vieira R, Alves R, et al. Mint (spp) germplasm conservation in Brazil. Res Bras PI Med 2006, 8: 27–31.

77. Gulluce M, Sahin F, Sokmen M, et al. Antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of the essential oils and methanol extract fromL. ssp. longifolia. Food Chem 2007, 103: 1449–1456.

78. Džamić AM, Soković MD, Ristić MS, et al. Antifungal and antioxidant activity of(L.) Hudson (Lamiaceae) essential oil. Bot Serb 2010, 34: 57–61.

79. Moradalizadeh M, Khodashenas M, Amirseifadini L, et al. Identification of chemical compounds in essential oils from stems, leaves and flowers ofvar. kermanensis by GC/MS. Int J Biosci 2014, 4: 117–121.

80. Soares PM, Assreuy MA, Souza EP, et al. Inhibitory effects of the essential oil ofon the isolated rat myometrium. Planta Medica. 2005; 71: 214–218.

81. Mokaberinejad R, Zafarghandi N, Bioos S, et al.syrup in secondary amenorrhea: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trials. Daru 2012, 20: 97.

82. Gordon W, Huitric A, Seth C, et al. The metabolism of the abortifacient terpene, (R)-(+)-pulegone, to a proximate toxin, menthofuran. Drug Metab Dispos 1987, 15: 589–594.

83. Niroumand MC, Farzaei MH, Amin G. Medicinal properties ofL. in traditional Iranian medicine and modern phytotherapy: a review. J Tradit Chin Med 2015, 35: 104–109.

84. Asgarpanah J, Ramezanloo F. Chemistry, pharmacology and medicinal properties ofL. Afr J Pharm Pharmacol 2012, 6: 1573–1580.

85. Fathiazad F, Azarmi Y, Khodaie L. Pharmacological effects ofseeds extract on isolated rat uterus. Iran J Pharm Res 2006, 2: 81–86.

86. Suhaimi AT, Ariffinb ZZ, Ali NAM, et al. Essential oil chemical constituent analysis of. J Eng Appl Sci 2017, 12: 5369–5372.

87. Udayaprakash N, Ranjithkumar M, Deepa S, et al. Antioxidant, free radical scavenging and GC–MS composition ofReinw. ex Blume. Ind Crops Prod 2015, 69: 175–179.

88. Espineli D, Agoo E, Shen C, et al. Chemical constituents of. Chem Nat Compd 2013, 49: 932–933.

89. Mustaffa F, Indurkar J, Shah M, et al. Review on pharmacological activities ofReinw. ex Blume. Nat Prod Res 2013, 27: 888–895.

90. Lemonica IP, Macedo AB. Abortive and/or embryofetotoxic effect ofleaf extracts in pregnant rats. Fitoterapia 1994, 65: 431–4.

91. de Pascual J, San Feliciano A, del Corral JMM, et al. Terpenoids from. Phytochemistry 1983, 22: 300–301.

92. Asili J, Emami S, Rahimizadeh M, et al. Chemical and antimicrobial studies ofL. andWilld. essential oils. J Essent Oil Bearing Plants 2010, 13: 25–36.

93. Fournier G, Baduel C, Tur N, et al. Sabinyl acetate, the main component ofL'Herit. Essential oil, is responsible for antiimplantation effect. Phytother Res 1996, 10: 438–440.

94. Lavy R. Thrombocytopenic purpura due tobean. J Allergy 1964, 35: 386–389.

95. Farghaly A, Hassan Z. Methanolic extract ofameliorates DNA damage in alloxan-induced diabetic mice. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2012, 16: 126–132.

96. Abdel-Monaim M, Gabr M, El-Gantiry S, et al., a new pathogen on lupine plants in Egypt. Afr J Bacteriol Res 2012, 4: 24–32.

97. Sharaf A. Food plants as a possible factor in fertility control. Plant Foods Hum Nutr 1969, 17: 153–160.

98. Al-harbi MS, Al-Bashan MM, Amrah K, et al. Impacts of feeding with(White Lupin) and(Egyptian Lupin) on physiological activities and histological structures of some rabbits' organs, at Taif Governorate. World J Zool 2014, 9: 166–177.

99. Moir JC. The obstetrician bids, and the uterus contracts. Br Med J 1964, 2: 1025.

100. Ligon EW. The action of lupine alkaloids on the motility of the isolated rabbit uterus. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1941, 73: 151–158.

101. Díaz JG, Ruiz JG, De La Fuente G. Alkaloids from. J Nat Prod 2000, 63: 1136–1139.

102. Faridi B, Alaoui K, Alnamer R, et al. Analgesic activity of ethanolic and alkaloidic extracts ofseeds. Int J Uni Pharm Bio Sci 2013, 2: 102–112.

103. Faridi B, Doudach L, Alnamer R, et al. In vitro cytotoxicity and free radical scavenging activity of ethanolic and alkaloidic extracts of. Int J Pharm 2014, 4: 7–12.

104. Welch KD, Cook D, Green BT, et al. Adverse effects of larkspur (spp.) on cattle. Agriculture 2015, 5: 456–474.

105. Khare CP. Indian Medicinal Plants: An Illustrated Dictionary. Springer Science & Business Media, 2008.

106. Srinivasan K. Fenugreek (): a review of health beneficial physiological effects. Food Rev Int 2006, 22: 203–224.

107. Kadam AB, Gaykar BM. Pregnane–a parent of progesterone fromLinn. Int J Pharm Sci Res 2017, 8: 5194–5198.

108. Ouzir M, El Bairi K, Amzazi S. Toxicological properties of fenugreek (). Food Chem Toxicol 2016, 96: 145–154.

109. Yadav UC, Baquer NZ. Pharmacological effects ofL. in health and disease. Pharm Biol 2014, 52: 243–254.

110. Khalki L, M’hamed SB, Bennis M, et al. Evaluation of the developmental toxicity of the aqueous extract from(L.) in mice. J Ethnopharmacol 2010, 131: 321–325.

111. Judzentiene A, Budiene J, Gircyte R, et al. Toxic activity and chemical composition of lithuanian wormwood (L.) essential oils. Rec Nat Prod 2012, 6: 180–183.

112. Bhat RR, Rehman MU, Shabir A, et al. Chemical composition and biological uses of Artemisia absinthium (Wormwood). Plant Hum Health 2019, 3: 37–63.

113. Hussain M, Raja NI, Akram A, et al. A status review on the pharmacological implications of: a critically endangered plant. Asian Pac J Trop Dis 2017, 7: 185–192.

114. Judžentienė A. Essential Oils in Food Preservation, Flavor and Safety. Academic Press, 2016.

115. Sajed H, Sahebkar A, Iranshahi M.Boiss. (Shirazi thyme)—an ancient condiment with modern pharmaceutical uses. J Ethnopharmacol 2013, 145: 686–698.

116. Shamsizadeh A, Fatehi F, Baniasad FA, et al. The effect ofBoiss hydroalcoholic extract and fractions in pentylenetetrazole-induced kindling in mice. Avicenna J Phytomed 2016, 6: 597.

117. Kavoosi G, Rabiei F.: chemical and biological diversity in the essential oil. J Essent Oil Res 2015, 27: 428–436.

118. Saedi Dezaki E, Mahmoudvand H, Sharififar F, et al. Chemical composition along with anti-leishmanial and cytotoxic activity of. Pharm Biol 2016, 54: 752–758.

119. Hashemi SA, Azadeh S, Nouri BM, et al. Review of pharmacological effects ofBoiss. (Thyme of Shiraz). Int J Med Res Health Sci 2017, 6: 78–84

120. Colás C, Monzón S, Venturini M, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled study with a modified therapeutic vaccine of(Russian thistle) administered through use of a cluster schedule. J Allergy Immunol 2006, 117: 810–816.

121. De la Rosa G, Martínez-Martínez A, Pelayo H, et al. Production of low-molecular weight thiols as a response to cadmium uptake by tumbleweed (). Plant Physiol Biochem 2005, 43: 491–498.

122. Sokolowska-Krzaczek A, Skalicka-Wozniak K, Czubkowska K. Variation of phenolic acids from herb and roots ofL. Acta Soc Bot Pol 2009, 78: 197–201.

123. Starr F, Starr K, Loope L.prickly Russian thistle chenopodiaceae. United States Geological Survey-Biological Resources Division, 2003.

124. Hageman JH, Fowler JL, Suzukida M, et al. Analysis of Russian thistle (species) selections for factors affecting forage nutritional value. J Range Manag 1988, 41: 155–158.

125. Webb AJ, Patel N, Loukogeorgakis S, et al. Acute blood pressure lowering, vasoprotective, and antiplatelet properties of dietary nitrate via bioconversion to nitrite. Hypertension 2008, 51: 784–790.

126. Manassaram DM, Backer LC, Moll DM. A review of nitrates in drinking water: maternal exposure and adverse reproductive and developmental outcomes. Cien Saude Colet 2007, 12: 153–163.

127. Sandhu NS, Kaur S, Chopra D.: pharmacology and phytochemistry–a review. Asian J Pharm Clin Res 2010, 3: 146–150.

128. Taylor T. Some features of the organization of the sporophyte ofL. New Phytologist 1939, 38: 159–166.

129. Fossum G, Malterud K, Moradi A. et al. Assessment report for the development of community monographs and for inclusion of herbal substance (s), preparation (s) or combinations thereof in the list. European Medicines Agency (EMA), 2008.

130. Nmila R, Gross R, Rchid H, et al. Insulinotropic effect offruit extracts. Planta Med 2000, 66: 418–423.

131. da Silva JAT, Hussain AI.(L.) Schrad. (colocynth): biotechnological perspectives. Emir J Food Agric 2017, 29: 83–90.

132. Prakash AO, Saxena V, Shukla S, et al. Anti-implantation activity of some indigenous plants in rats. Acta Eur Fertil 1985, 16: 441–448.

133. Dehghani F, Azizi M, Panjehshahin MR, et al. Toxic effects of hydroalcoholic extract ofon pregnant mice. Iran J Vet Res 2008, 9: 42–45.

134. Mahendra P, Bisht S.: Traditional uses and pharmacological activity. Pharmacogn Rev 2012, 6: 141–146.

135. Upadhyay PK. Pharmacological activities and therapeutic uses of resins obtained fromLinn.: a review. Int J Green Pharm 2017, 11: S240–S247.

136. Iranshahy M, Iranshahi M. Traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology of asafoetida (oleo-gum-resin)-a review. J Ethnopharmacol 2011, 134: 1–10.

137. Keshri G, Bajpai M, Lakshmi V, et al. Role of energy metabolism in the pregnancy interceptive action ofandextracts in rat. Contraception 2004, 70: 429–432.

138. Benzie IF, Wachtel-Galor S. Herbal Medicine: Biomolecular and Clinical Aspects. CRC Press, 2011.

139. Tchacondo T, Karou SD, Batawila K, et al. Herbal remedies and their adverse effects in Tem tribe traditional medicine in Togo. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med 2011, 8: 45–60

140. Baser K, Kirimer N, Tümen G. Pulegone-rich essential oils of Turkey. J Essent Oil Res 1998, 10: 1–8.

141. Benkaci-Ali F, Baaliouamer A, Wathelet JP, et al. Chemical composition of volatile oils from AlgerianL. seeds.J Essent Oil Res 2010, 22: 318–322.

142. de Cássia da Silveira e Sá R, Andrade LN, de Sousa DP. A review on anti-inflammatory activity of monoterpenes. Molecules 2013, 18: 1227–1254.

143. Kooti W, Moradi M, Peyro K, et al. The effect of celery (L.) on fertility: a systematic review. J Complement Integr Med2017, 15; 1–12.

144. D'cruz SC, Vaithinathan S, Saradha B, et al. Piperine activates testicular apoptosis in adult rats. J Biochem Mol Toxicol 2008, 22: 382–388

:

TPM, traditional Persian medicine.

:

There are no conflicts of interest.

:

Ensiye aafi, Malihe Tabarrai, Mehran Mirabzadeh Ardakani, et al. Evaluation of scientific evidence for abortifacient medicinal plants mentioned in traditional Persian medicine. Traditional Medicine Research 2020, 5 (6): 449–463.

:Cuihong Zhu, Xiaohong Sheng.

: 11 October 2019,

8 December 2019,

:10 January 2020.

Seyede Nargess Sadati Lamardi. Department of Traditional Pharmacy, School of Persian Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences,No.27, Sarparast St., Taleqani Ave., Tehran, 1417653761, Iran. E-mail: n_sadati@tums.ac.ir.

10.12032/TMR20200106150

Traditional Medicine Research2020年6期

Traditional Medicine Research2020年6期

- Traditional Medicine Research的其它文章

- Green coffee bean hydroalcoholic extract accelerates wound healing in full-thickness wounds in rabbits

- Gastrointestinal effects of Artemisia absinthium Linn. based on traditional Persian medicine and new studies

- Effects of chicory (Cichorium intybus L.) on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- Jadwar (Delphinium denudatum Wall.): a medicinal plant

- Is “Pangolin (Manis Squama) is not used in medicine" an improvement in the protection of precious and rare species or an improvement in the safety of using medicine?

- The gap between clinical practice and limited evidence of traditional Chinese medicine for COVID-19