Towards Semiotics of Art in Record of Music

Jia Peng

Jinan University, China

Abstract Record of Music, a classic in traditional Chinese art theories, has established an aesthetic model of “Wu gan”, which offers a unique and important perspective for how feelings are sparked by things and artistic creations come into being thereafter. Being re-examined in the context of Peircean semiotics, such a model reveals the mechanism of feeling and meaning generation of artistic semiosis, and could, therefore, provide an alternative interpretation of the interpretative semiotics initiated by Charles S. Peirce.

Keywords: Wu gan, artistic creation, feelings, external objects, Record of Music, mind and body, embodied perception

“Wu gan” (物感, the “theory of feelings being stirred by external objects”) originated from The Book of Rites: Record of Music (《礼记·乐记》), a prominent work in classical Chinese art theories. Record of Music represents the first of its kind to expound on how external objects arouse the sentiments of mankind to produce classic aesthetic works that fall within the category of art semiotics, then functions as a paradigm of “Wu gan” theory for future studies. It was stated by Huang Weilun that the creative process followed this sequence: “Stillness of Mind/Moved by Objects/Emotional Affection/Generation of Music” (Huang, 2012, p. 110). The phenomenon of feelings sparked by external objects comes into being in the framework of Chinese philosophy on the “similarities between mankind and external beings”. One’s heart is real and transcendental, thus paving the way for such stirred emotions (Liu, 2006, pp. 22-27). It can be said that Record of Music has presented a unique Chinese explanation of how an artistic work is created when the heart feels touched by external objects. Then what is the mechanism of emotion generation? How does such emotion exert its impact on the later creation process? What are the encoding and decoding principles for artistic work creation? From the perspective of semiotics, this paper attempts to propose a semiotic pattern of “Wu gan” and to unravel the encoding/decoding rules of artistic work creation.

1. A Philosophical Paradigm of the Semiosis of “Wu Gan”: Mind-Body Dualism with Embodied Perception

James Liu, a contemporary American sinologist, has judiciously placed the Chinese aesthetic notion “Wu gan” in the context of universal literary theories. He took Record of Music (《乐记》, Yue Ji), Poem Latitude (《诗纬》, Shi Wei), and The Literary Mind and Carving of Dragons (《文心雕龙》, Wen Xin Diao Long) as telling examples of the metaphysical paradigm of Chinese literary theories, and deemed that “xin” (心), the sensory organ of poets and musicians, be it mind or heart, bears a tinge of metaphysical elements (Liu, 2006); “xin” is the matchmaker of the external world with poetry and music. If the external world is perceived and represented by “xin” as the main body, then the premise of “Wu gan” theory goes to mind-body dualism of Chinese literary traditions. Mind-body dualism is the basis for the artistic semiosis proposed in Record of Music which writes that music originates from the “xin”, the intentional carrier of sense and the fountain of feelings inspired by objects (物). “Object” denotes real images and beings in the natural world, such as thunderbolts, storms, vegetation, birds, beasts, mountains and water. Although these physical objects are formed by the forces of yin (阴) and yang (阳) rubbing each other and heaven and earth stirring each other, they could only be perceived by the participation of “xin” in the recognition of these signs. In this sense, the paradigm of mind-body dualism in Record of Music is similar to the subject-object dualism in western semiotics at least in depiction of the perception process of objects.

However, in contrast to the dichotomous subject-object dualism in the West, the mind-body dualism paradigm in Record of Music is a fusion of mind and object in Chinese philosophy; one’s xin can be moved by external objects and bear fruits in concrete forms, and thus creation is derived from its collision and fusion with objects. But how is the fusion between xin and object possible? To ascertain this, one has to get a clear picture of the definition of xin recorded in Chinese theories of literature. Xin refers not only to the abstract and logical mind, but also to the integration of the body and the sentient heart that is capable of embodied perception and experience. In short, it integrates body, mind and heart. According to Kong Yingda (2000), xin is the root adorned with qi (气), which represents not only the transcendental yin and yang as the origin of the metaphysical mentality and the universe, but also the wind, rain, obscurity and light as the embodiment of physical being with the embellishment of flesh and blood; it can therefore be derived that “xin” functions physiologically as the spleen, emotionally as a sensor that could feel the gentle touch of breeze, and logically as a court that could tell right from wrong. It is the feelings and the perceived senses that can be employed for further estimation; it does not refer merely to the heart that unshackles the restraint of flesh, nor the heart that intersperses the flesh asserted by Descartes, rather it is one that forms an inclusive whole together with the body, and that whole enables the flesh to pierce through us and to hold us (Merleau-Ponty, 2000, p. 783), which makes it possible for us to have holistic feelings and deliberations. Judging from the foregoing demonstrations, the concept of “soul” recorded in Chinese classical philosophy is both corporeal and transcendental, which could offer modern studies much food for thought.

“Mind-fasting” (心斋, xin zhai) mentioned by Chuang-tzu (also written as Zhuangzi) and Confucius is a concept that blends the body, mind and soul. The cognition of the “object” perceived by “xin” is three-layered, a fact that explains the integration of body, heart and soul by dint of “xin” itself:

In unifying your will so single-mindedly, you ceased listening to things with your ears and instead listened with your mind. If analogously you cease listening with your mind and instead listen with your vital breath-energy, your hearing will go no further than the ears, and your mind will go no further than interlocking with its objects like a tally. For this vital breath-energy is an empty openness that waits for whatever may come, able to depend on all things. The Course is the only gathering of the empty openness. That empty openness is the fasting of the mind. (Zhuangzi, 2020, p. 44)

James Liu proposed a tenable view that the first layer of mind-fasting connects with the body’s sensory perception, the second with conceptual thinking, and the third with the intuitive cognition developed after long periods of cultivation (Liu, 2006, p. 50). However, he failed to pinpoint the interdependence of these three layers of cognition. The top layer of cognition generated by “mind-fasting”—the main subject of the cognitive process—is arrived at on the basis of the former two layers of cognition: the emotions stirred by “mind-fasting” extend from the physical perception of iconicity and indicative gauge to prescriptive and metaphysical comprehensions. This kind of continuum of semiotic meanings conforms to the semiosis of C. S. Peirce and all the more illustrates that the “xin” itself is an integrated, multi-faceted subject in Chinese classical theories of literature.

This aesthetics of mind-body dualism with “embodied perception” is ubiquitous in classical Chinese works of art and literature, and more so in the expositions of art activities. It is reasonable for Li Shuming to deem that this paradigm which “integrates music and heart and caters to both subject and object” has depicted the evolutionary process of this artistic activity from perception to mentality (Li, 1984, pp. 27-28). In Guo Xi’s view, one of the core elements of landscape painting lies in the technique of personal contacts with the landscape: if one aims at reproducing the scenery with brushes, one has to engage oneself in “untold outings and extensive browsing” to personally feel the shape and spirit of the scenery; only then could one be inspired by the images “stored vividly in their minds” and see through the “essence of landscape” (Guo, 2010, p. 36). Li Mengyang writes: “emotion is stirred by encounters”, “By encountering a being, emotion is stirred within, comprehension follows, then something just clicks, and music bursts out, that is called the generation following encounters” (Li, 2009, p. 2): the object stimulates embodied perception and sparks “emotion” within the heart and echoes of the mind, and this spark of inspiration is preserved in music. Yet the expositions on the coconstructive relation between “body” and “mind”, from “tangible” and “intangible” of Laotze’s concept about body, to the “Five Elements” (五行) of Confucianism and Wang Yangming’s philosophy of the mind, in traditional Chinese theories of literature are intertwined in a mutually supportive system. The vast and complex system is far beyond the scope of this present paper. As a matter of fact, the author never intends to touch upon the co-constructive relation between “body” and “mind” or embark on the grand exploration into the aesthetics of embodied perception, but rather takes these two as the starting point to construct the semiotic pattern of “Wu gan” following the semiotic approach.

Record of Music mentioned at the beginning the concept of “xin”: “All music originated from xin” (Chen, 2006, p. 586). “Xin” here refers to the blending of “mind” and “heart”: for one thing, it deems that all music symbols arise from sense, a view quite congruent with Saussure’s phenomenology: signs exist not beyond human thoughts, but represent the very product of thoughts—which underlines the impact of sense generated by “mind” on the creation of music symbols. For another, Record of Music writes in the following part “all human emotions are inspired by external objects. Such sparked emotions are then embedded in sounds” (Chen, 2006, p. 586). The touched heart reveals its role as the fountain of emotions, and the act of “embedding such emotions in sounds” is their representation in music symbols, that is to say, the creator of music symbols goes for disparate tunes to convey their inner feelings:

thus if immersed in sorrow, the music produced is fast and muffled; immersed in cheerful moods, the music produced is soothing and gentle; immersed in delight, the music produced is jubilant and flowing; immersed in rage, the music produced is rough and intense; immersed in reverence, the music produced is sincere and humble; immersed in love, the music produced is amicable and tender. (Chen, 2006, p. 586)

The emotional expression is realized by the combination of conventional music symbols in this process which represents the thirdness of semiotics. The paper is to elucidate this aspect in detail.

Then how does an external object work on human mind to inspire embodied feelings? According to Record of Music, the differentiated emotions stirred by external object come down to human perceptions toward the “qi” of that object, for in the formation of the whole universe,

some force guides motion and stillness, and thus the vast is separated from the small. Formless objects of the same type are gathered together like tangible beings, and thus enjoy disparate life spans. Those up in the heaven are represented in images and those down on the ground in concrete forms; following this line of thought, rites are the one that differentiate heaven from earth. The qi of the ground goes up to heaven, and the qi of heaven the other way around. The former is yin, the latter is yang. By collision of yin and yang, the earth and heaven reverberates with the sound of thunderbolt, with the advent of wind and rain, the course of four seasons and the warmth of sunlight and moonlight, all things come alive. (Chen, 2006, p. 589)

That is to say, everything on earth is brought into being by the collision of yin and yang. Humans’ feelings toward external objects are embedded in their perceptions of the interlinked spirits of all objects on earth. This kind of feeling directly touches the heart by dint of the body. As mentioned earlier, “qi” in Chinese philosophy is the basic element that constitutes everything in the universe. It can be deemed as metaphysical or concrete. There is a saying in On Balance (《论衡》, Lun Heng), “the qi of heaven and earth is interlinked and gives rise to everything in the universe” (Wang, 1974, Chapter 18), that basic element connects with human body and constitutes the primordial qi which functions as the very linkage with “Tao”: “Primordial qi, derived from heaven, together with essence derived from food, make for the body” (Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine of Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, 1986, p. 465). It fills the human body and interacts with the metaphysical “Tao”, from which emotions are generated. This is exactly what Record of Music writes,

whenever vile music touches the listener, disobedient feelings arise thereof; once that disobedience is revealed, obscene music would become prevalent. While whenever bright music touches the listener, obedient feelings arise thereof; once that obedience exposed itself, harmonious music would thrive. Just as the singer and their followers interact with each other, evil interacts with crooked spirit, and integrity with others. Everything can be subsumed under a category; and the essence of everything lies in their interactions with the same categories. (Chen, 2006, p. 581)

The concept of “interactions between categories of the same feather” posited on the premise of “qi” is the “essence of everything” and the mechanism produced by embodied perceptions of mind-body continuum.

Record of Music has detailed exposition on the transformation of embodied perception: “A man is endowed with spirit and intelligence, but the change of mood from sorrow and anger to joy and delight is unpredictable. A man’s heart is moved by external beings and produces emotions consequently” (Chen, 2006, p. 582). “Spirit” is pertinent to the body and acts as the subject for emotion generation and cognitive ability. As the saying goes, “all those living between heaven and earth demonstrate the quality of spirit and are bestowed with intelligence”. Therefore, Record of Music placed “spirit” and “intelligence” side by side, and made signs the carrier of mindbody continuum. However, before the semiotic process, or in other words, the generation of embodied perception, the subject is void of any emotions, a confirmation of “unpredictable courses of sorrow, joy, delight and anger”. Once the subject experienced embodied feelings toward the “object”, he or she was then moved and further cognition of this “object” thus emerged: That is what they call “the formation of relevant emotions”, i.e. the differentiation, identification and comprehension of the “object”, the cognition garnered by mind and heart: “Honesty, loyalty, tolerance, charity, magnanimity, and clemency are referred to as intentions of the heart” (Guanzi, 2009, p. 77). “Intention of the heart” is discriminative and intellectual, emotional and experiential, and it is closely related to the “rise of emotions”. This semiosis advanced step by step is dominated by embodied and interactive subjects, which stands as the most unique and conspicuous part of the aesthetic theory proposed by the Chinese concept of “Wu gan”.

2. Semiosis of “the Status of Being Touched by External Objects and the Subsequent Welling-Up of Emotions”

As for the creation process of music symbols, Record of Music writes: “Music arises from sounds, and comes down to emotions sparked by objects” (Chen, 2006, p. 581). That is to say, “xin” represents only the possible conditions for the creation of “music”. The necessary condition for the composition of “music” lies in the encounter and interaction between “xin” and “object”. Prior to this stage, one’s disposition is marked by serenity, as the saying goes: “a man’s disposition is serene from the beginning”. That gave rise to one question: how to explain “disposition” appearing in that phrase? Confucianist thinkers hold different understandings toward the definition of “disposition”. Zhu Xi deemed that disposition refers to the evil or good nature of humans (Zhu, 1986, Chapter 28), while Zhang Zai’s theory of “xin comprising of senses and sentiments” regarded it as senses (See Zhu, 1986, Chapter 98). Overall, “serene disposition” tells not the stillness of consciousness or intentionality, but rather emphasizes their very being: for what follows that line is “different emotions arise from within the heart touched by external objects, that’s the born ability of disposition”. In other words, the denotation of “disposition”, be it “nature”, “instinct” or “sense”, shows the tendency for interaction with “external objects”, and the inspiration of “objects” on the “heart” benefits that tendency in return, which confirms the views of phenomenology: at the first phase of symbol generation, intentionality embarks on its search for relevant attributes on the part of objects whose attributes rewarded the search process, and meanings are thus acquired. This is a two-way process referred to by Zhao Yiheng as “formal intuition” (Zhao, 2015, p. 26). This process is interactive and concurrent. It is hard to define the sequence of “object” and “xin”.

Due to the emphasis laid on “object” in Record of Music, many literati took it for granted that “object” preexisted “xin” in its proposed aesthetic process. For instance, Huang Weilun regarded “object” as the “trigger” for “the status of being touched by external objects and the subsequent welling-up of emotions”, thus it demonstrates features of necessity and preexistence, and “possesses the meaning of firstness” (Huang, 2012, p. 126). However, if resorting to Zhang Zai’s theory of “xin comprising of senses and sentiments”, the very existence of “disposition” which forms a part of “xin” can be seen prior to “the status of being touched by external objects”. The Book of Rites has given its explanation for the origin of “disposition”: “Virtue is the root of disposition”; given its ethical and contractual origin, “disposition” must be subsumed under “mind” and preexists before “the status of being touched by external objects and the subsequent welling-up of emotions”. Therefore, “serene disposition” refers not to the dynamic status where it is in no pursuit of meaning-acquisition objects, but to the limpid and peaceful disposition or sense, in Li Zehou’s words, “the desire for worldly objects grows in mankind’s nature, which conforms to the saying of Xuncius ‘man is born with desires’” (Li & Liu, 1984, p. 391). Moreover, “man is born with a serene disposition”, “may have something to do with the saying ‘proper perception of objects arises from an open, constant and serene mindset’ in Xunzi” (Li & Liu, 1984, pp. 391-392). That is to say, “serene disposition” puts more emphasis on the limpid and peaceful state of mind, and when touched by “external objects”, it can give rise to emotions and a switch of status from serenity to dynamics, from disposition to sentiments: indicating that art creation is a sequential and dynamic semiosis.

Yet, can music symbols be created simply by the interaction between “xin” and “object”, specifically by the encounter of sense and object and the perception of the former towards the latter? Record of Music depicts this gradual process in great detail:All music originated from xin. All human emotions are inspired by external objects. Such sparked emotions are then embedded in sounds. All kinds of sounds work in concert with one another, giving rise to intonation and orderliness—what we call tunes. These tunes when performed in a certain manner and accompanied by dances with stage props are called music. (Chen, 2006, p. 581)

The heart feeling touched by external objects constitutes the first step in the symbolization process. The pertinent attributes of the object are acquired by the subject by embodied perception based on the interaction between the “qi” of both parties: the subject obtains the concerning properties of the object by feeling its “qi”, as “qi” casts changes on worldly objects which in turn move the heart of humans’, the interaction between their “qi” enables the subject to elicit certain traits of the objects.

The acquisition of pertinent quality is firstness or rather the generation of iconicity viewed in the framework of Peirce’s semiotics. Yet, does the act of obtaining relevant qualities of the object after “being moved by it” remain on the level of iconicity? Peirce defined iconicity as follows:

By a feeling, I mean an instance of that kind of consciousness which involves no analysis, comparison or any process whatsoever, nor consists in whole or in part of any act by which one stretch of consciousness is distinguished from another, which has its own positive quality which consists in nothing else, and which is of itself all that it is, however it may have been brought about; so that if this feeling is present during a lapse of time, it is wholly and equally present at every moment of that time. To reduce this description to a simple definition, I will say that by a feeling I mean an instance of that sort of element of consciousness which is all that it is positively, in itself, regardless of anything else. (CP 1.306)

As the foregoing paragraphs, “the status of being touched by objects” is based on the perception of “qi”. The concept of “interactions between categories of the same feather” has erected a hierarchy among categories. It could thus be inferred that “the status of being touched by objects” belongs to secondness, the indexical and judgmental semiotic process.

But if one goes on to peruse the differences drawn by Peirce himself between firstness and secondness, one may come to realize that the encounter of subject and object belongs only to firstness without any doubt. Peirce regarded the perception of “It is red” as firstness and “This is red” as secondness, i.e. the feelings toward the quality of object belong to firstness while the classification of and reaction to that certain quality belong to secondness, for secondness, which is indexicality, “…would be more accurately described as the vividness of a consciousness of the feeling—is independent of every component of the quality of that consciousness” (CP 1.306). This kind of feeling endowed with vitality is known as emotion “sparked by the stimulation of external objects”. It is indexical and directional, and pushes the subject to express itself with actions by “embedding it in sounds”. It can thus be concluded that the process from “feeling touched by external objects” to “stirring emotion within one’s heart” is a continuous semiotic process of development spanning firstness and secondness: the tow happens almost simultaneously in real perception practices (such as the instant feeling of tranquility at the sight of dancing bamboo), but logically, “the status of feeling touched by external objects’ preexists ‘the welling-up of emotions within one’s heart”.

Then how to interpret the categoricalness of the interaction between the “qi” of the object and subject in the first stage featured by “interactions between categories of the same feather”? This has something to do with one basic concept in biosemiotics: Umwelt. The notion of Umwelt was put forward by Jakob von Uexküll, the founder of biosemiotics. It means the surrounding and self-created world of organisms which is covered by their perceptions, and this meaningful world is constructed atop semiotic relations. Taking body as the boundary, the surrounding world can be divided into two parts: the inner world and the outer world, or rather perceptive and operative world, and how animal species perceive and interact with the surrounding world is determined by the set functional cycles (Uexküll, 1926, p. xv). Although the semiosis of animal species is predominated by indexicality and directionality (p. 9), indexical sign is formed after the relevant qualities of the object being perceived by the subject. Only in this way can the subject make a subsequent judgement. As pointed out in the previous part, “qi” is a concept partaking both physical and metaphysical traits. If we consider it as a component of prior schematismus of Chinese “cultural umwelt”, it presupposes that the human, as cultural perceiver, feels the semiotic object by “interaction of qi” and connects with it with the categorical schematismus, and captures initially the relevant qualities of the object, thus obtaining the firstness of the semiosis process.

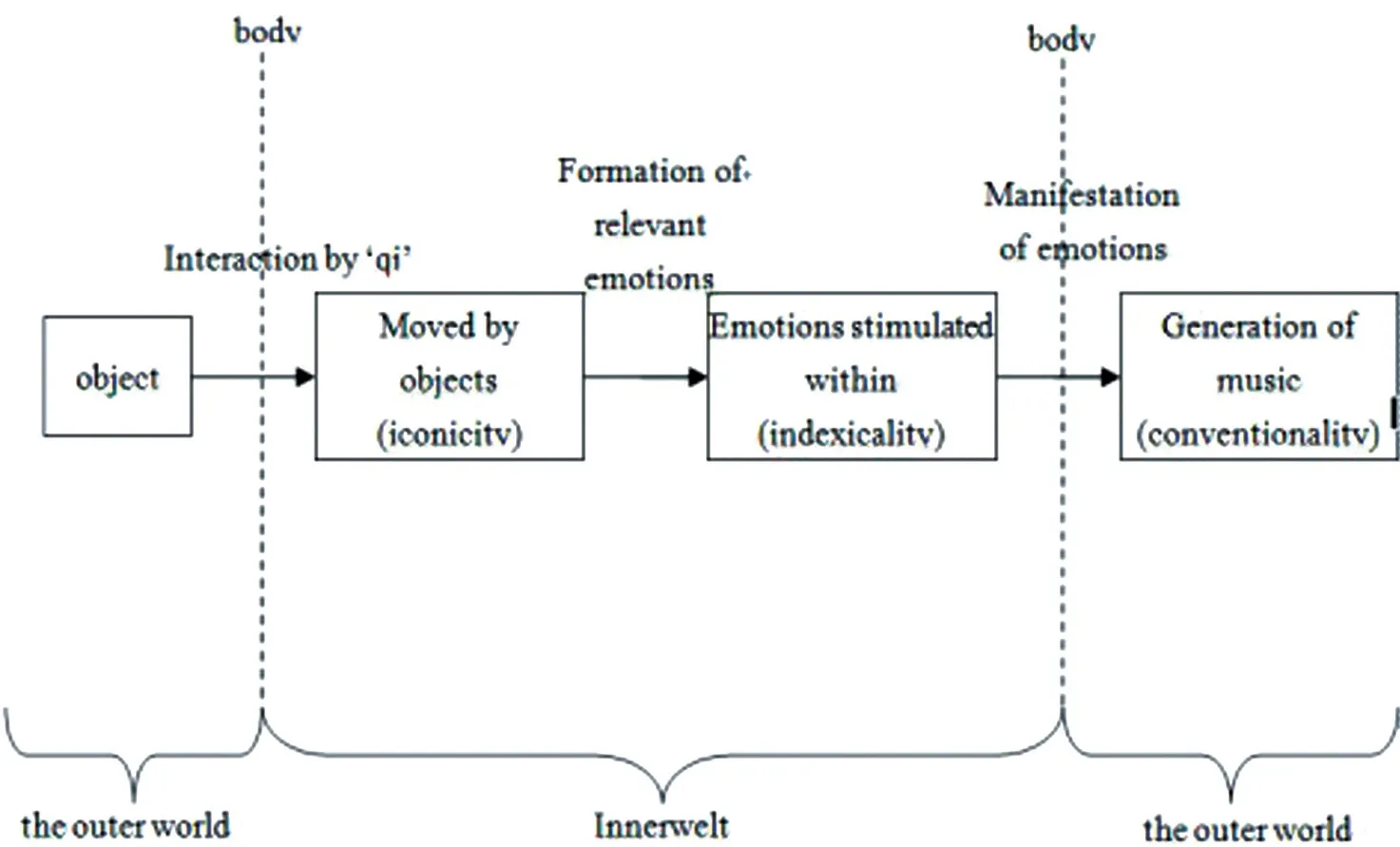

Yet, as demonstrated in the theory of “Wu gan”, the status of “feeling touched by external objects” is only the first phase in the art creation process, after that “emotions are generated consequently”, indicating the emergence of distinctive judgements and sentiments, which marks the second stage—“welling-up of emotions”. The rising up of emotions is the “vivid” reaction of the subject towards the object; such emotion is direct, natural and classified. As the saying goes, “latent emotions, likes, dislikes, joys, sorrows, angers and happiness are called natural disposition”. With heart brimming with emotion, one has to let it out as “emotions are stimulated within but manifested outside”. Just as an animal has to resort to its body to convey the designated sign, mankind is also bound to express that stirred emotion with body gestures or in language and artistic signs, while the latter manifestation is accompanied by thirdness; it is sure to be conventional. The following figure depicts that process:

As is shown in the figure, the semiotic process of “feeling touched by objects”, “welling-up of emotions” and “generation of music” is triggered by embodied perception of the semiotic subject who acquired relevant qualities of the object (iconicity emerges), produced differentiated senses and sentiments (indexicality arises), and then presented them in the form of symbols (on the basis of conventionality); while “qi”, part of the Chinese cultural meta language, predetermines the formation of “Wu gan”—the way by which relevant qualities of objects “interact in the form of qi” and are obtained by the perceiver. So how does the “generation of music” unfold after “emotions being stirred up within the touched heart”, i.e. how is the creation process of music depicted in Record of Music? In fact, that is a question on the production of artistic texts, during which the most paramount encoding principles are the grammar of music and ethical rules.

3. The Musical Encoding and Decoding Principle in Record of Music: A Comparative Study of Music Notes Being Devoid of any Emotions

When one’s heart is surging with strong emotion, one will spontaneously verbalize it in signs, such is the process referred to as “embedding emotions in sounds”. At that stage, “sound” is sign in disarray, the verbalization of emotions; it can be purely physical and an analogue of the animal “pre-musical” sign, which bears out the saying “it is animal that can distinguish sound yet has not the ability to admire music” (Chen, 2006, p. 583). But the bigger difference between a human’s musical signs and an animal’s “pre-musical” ones lies in their decoding rules, for even the decoding rule of a single musical sign is conventional and cultural; we have already developed a set of music guidelines which govern the utilization of different tones to convey a large array of emotions. The intonation of musical signs functions as an instrument to convey emotions, a process constrained by the guiding principles of the musical system. Erkki Pekkila once said, “a given chord bears a designated meaning, the sound of a violin also exudes a specific meaning… Music is capable of conveying strong emotions” (Pekkila, 2012, p. 5). Governed by this conventionality, an artist will try to compose his own music within the boundary of music system, thus entering the stage where “all kinds of sounds work in concert with one another, giving rise to intonation and orderliness which are what we call tones” (Chen, 2006, p. 598).

During this stage, intonations generated in the interaction and collision of sounds are composed in line with the decoding principles of music, thus contributing to the rudimentary sense of sequence and beauty. Record of Music writes “music cannot stand alone without form” (Chen, 2006, p. 598), i.e. musical signs have to be conveyed in textual forms, and detached signs themselves are not sufficient for meaning expression; the articulation of “sound” is the draft version of the music text. The basic language of music employed in the musical text incorporates what have been mentioned in Record of Music as “inflection and flatness”, “abundance and frugality”, “high-pitch and mellowness” and “rhythm”, which refer to the ups and downs of musical tones, the complex and concise combination of instruments, and the intensity and tempo of sound; the musical texts composed with this set of music grammar already bear a tinge of beauty in form. While even musical text is now presented with a “form”, still it could not be counted as “music”, for the encoding of music must conform to higher ethical rules, as “disorder would arise for lack of guidance of the form” (Chen, 2006, p. 598). If music cannot perform the function of ethical cultivation, then such music would end up in the ears of “ordinary folks who know not music but the sound” (Chen, 2006, p. 598). What is the “Tao” of music? This leads us back to the metalanguage which “interacts with qi”. Sound and “qi” are mutually interactive; thereby the ethical value of “qi” makes the ethical value of “music”. Then how does this interaction unveil itself? In musical forms, it is accompanied by all kinds of stage props; in ethical terms, “rites and music share the same roots when employed in governance of country and people” (Chen, 2006, p. 596), therefore, it must conform to harmony between heaven and earth and orderliness among various objects: “music shows harmony between heaven and earth; rites show orderliness. With harmony, everything is showered with cultivation; with orderliness, everything is separated apart” (Chen, 2006, p. 586). Musical text produced in line with this ethical rule is thus able to cultivate, to carry with it various ethics related to “degree of intimacy, places in the social hierarchy, respect for seniority, and differences in gender” (Chen, 2006, p. 588), to help govern the country and guide the people to good deeds.

Because ethicality constitutes the metalanguage rule of Confucianism, Record of Music deemed the encoding of ethical norms to be mandatory and surefire:

when subtle, short and intense music prevails, people would feel depressed; when soothing, relaxed, gorgeous music of simple rhythm prevails, people would feel peaceful and delighted; when inspiring, exciting and grand music prevails, people would be resolute and steadfast; when decent, solemn and sincere music prevails, people would feel respectful; when cheerful, sonorous, fluent and gentle music prevails, people would be benevolent; when dissolute, scattered, and fast-paced music prevails, people would engage in licentious behaviors. (Chen, 2006, pp. 588-589)

The meaning of musical texts must be interpreted in light of ethical rules of the Confucian canon, yet, with the evolution of theories regarding classic arts, this compelling encoding principle has been more or less challenged by various viewpoints, especially that of Ji Kang’s Music Notes Being Devoid of any Emotions (《声无哀乐论》, Sheng Wu Ai Le Lun), which raised a powerful rebuttal of the mandatory encoding of ethics in music creation.

Ji Kang, an iconic figure of Wei-Jin demeanor, was renowned for his uninhibited and unconventional call for “transcending all Confucianist ethical norms and allowing the unchecked sprawling of natural disposition”. He raised the criteria for evaluating and appreciating a music work: the harmony between heaven and earth. “Harmony” refers to the state where the tunes of heaven, earth and everything in between work in concert with one another. It is a peak that all music strives to reach. It has nothing to do with ethics or rites. In the opening chapter of On the Absence of Sentiment in Music, Ji Kang had defined “music” as a pure and self-sufficient object to which mankind added emotions:

Heaven and earth operate as one unity, from which everything in between flourishes. With the passage of seasons, five elements come into shape, which are presented in five colors and articulated in five tones. The articulation of tone is like the diffusion of flavors. The good and bad about tone would inevitably subject to vagueness and confusion, but the noumenon of tone itself remain the same without any change. Then how could its essence be varied by others’ reactions and emotions? (Ji, 1980, p. 2)

“Music” is the product of the evolution of yin-yang and the five elements. It is a natural self-sufficient being whose tune and intensity remain constant regardless of external changes: a fitting description of music’s physical property of having its own “noumenon”. Ji Kang drew an analogy between the constancy of music’s noumenon and the flavor of spirits:

By mere squashing, beads of sweat trickle down the muscles, and care not about joy or sadness. Just as the cloth sifters used for spirits filtering may vary in each case, but the spirits produced taste no difference. It is the same with “music”. Originated from the body, how come it is endowed with sadness or joy? (Ji, 1980, p. 19)

In contrast with the rollercoaster-like emotions and feelings, the existence of “music” is constant, and its own properties are detached from outside violations or influences. To underline the pureness of its property, Ji Kang went on to propose that “music” is independent from human feelings, “if so, music and inner feelings actually take two disjoint paths, how could we mismatch the supreme harmony of music with human emotions and impose on them false names?” (Ji, 1980, p. 22) In his view, the beauty of music was not derived from emotional projection, but from abiding by its own rules. The “harmonious combination of tunes” exudes an artistic appeal and “touches human heart the most” (Ji, 1980, p. 23).

To achieve this “harmonious combination”, what is the encoding and decoding principle for musical texts to follow? In Music Being Devoid of any Emotions, Ji Kang emphasized the pitch, rhyme and inflection of tunes, as well as the aesthetic beauty brought along by the combination of tunes:

Pipa, Zheng and flute send out abrupt and sonorous tunes with changeable and fast rhyme. The fast-paced rhyme led by high-pitched tune would elicit outward agitation and inner excitement. Just as the sound of Lingduo, a percussion instrument, alerts people and the sound of drum and bell stuns people, “the beating of a war drum recalls back the commander-in-chief”. For the high and low pitch relate the audience of intense or serene feelings. Pipa has a low draw-out sound with a clear and changeless tone. If not listening intently, one could not fully appreciate the beauty of clear tune, so the audience would gain a serene and peaceful state of mind. Different tunes came from different instruments. The tunes of Qi and Chu were mostly serious and changeless, which would elicit a constancy feeling and high concentration. Pleasant music blends various melodious sounds and combines five tunes, and its noumenon is rich and exerts extensive impact. Due to the combination of various pleasant sounds, the audiences feel constrained by disparate circumstances; for its convergence of five tunes, the audiences are thus entertained, relaxed and satisfied. However, the tunes are featured by monotonous, complicated, sonorous, low-pitched, pleasant and repugnant sounds which elicit reactions from the audience emotions like agitation, serenity, constancy and relaxation. It’s like the relaxed state when browsing around the cities; by listening to the tunes, one would gain a peaceful and contemplative feeling with a dignified look. That is to say, the noumenon of sounds lies in the pace of rhyme. The emotional response of audience is limited only to agitation and serenity. (Ji, 1980, pp. 52-53)This is consistent with what was mentioned in Record of Music: “inflection and flatness”, “abundance and frugality”, “high-pitch and mellowness” and “rhythm”, i.e. both Music Notes Being Devoid of any Emotions and Record of Music deemed that the grammatical system of music, the encoding and decoding principle of musical texts, can arouse emotional response on the part of the audience. However, the difference lies in that Record of Music regarded a fine work of music as one that could stimulate or express feelings of joy, anger, sorrow and sadness by giving vent to inner emotions to arrive at the orderly and measured ethical value, while the Music Notes Being Devoid of any Emotions regarded the natural emotional response as being brought about by “restlessness and quietness, constancy and loose” dispositions, which were un iversal reactions to music, but feelings of joy, anger, sorrow and sadness, although being common human emotions, result in conventional and cultural products in their interactions with music: “local customs vary from places to places, laments in songs express disparate meanings, which when disrupted, someone would be elated, while others be saddened, whereas, their inner feelings of sorrow and happiness are the same” (Ji, 1980, p. 22). Because of this, people from different places report inconsistent feelings to music. Therefore, musical creation cannot manage to express proper feelings and function ethically to make people “happy yet within a reasonable boundary, blue yet not overwhelmed”: “the audience reacts to tunes with agitation and serenity”, thus music should be celebrated for its aesthetic role, not its ethical one.

However, as many scholars have pointed out, the strong ethical value of Chinese cultural semiotics functions as the core metalanguage with its potent encoding principles of ethical signs. Zhu Dong deemed that the Confucianist ritual and musical semiotic systems were merely the philosophy of one school among hundreds of schools of thought, but gradually made their way into the fundamental ideology of the cultural system (Zhu, 2012, p. 69). Taoism, as another metalanguage text of this semiotic system, was ethically encoded, while the theorists of Wei and Jing which partake the thoughts of Lao-tzu and Chuang-tzu based their ethical semiotic principles on unveiling “Tao” by transcending rites and music to realize the harmonious combination and interaction of the “qi” of heaven, earth, mankind and everything in between. In the ending chapter of Music Notes Being Devoid of any Emotions, the other principle for ethical encoding of music creation was revealed: Ancient emperors take over the mandate of heaven and rule over all things on earth. They follow the principle of simplicity and practicality and govern by doing nothing that goes against nature. By doing so, emperors in high position could rule over their obedient subjects. Gradually, man and nature are bonded in a harmonious relation, showering blighted things with raindrops and the whole world and mankind with happiness. When filthy things were eradicated, the people would be immersed in peace and joy, as well as pursue their own well-being and follow their own accord the great Tao. People entertain loyalty and righteousness without consciously knowing why. They resort to singing and dancing to voice their feelings of inner peace and outer serenity. (Ji, 1980, p. 78)

The art of music acts as a vital means in the “pursuit of nature”. Its ethical principle aims not at fashioning ritual and musical systems, but at freeing people from the conventional “reasonable” and “measured” emotional response outlined by the ritual and musical rules, as well as bringing people to a harmonious state with heaven and earth. Considering the encoding and decoding rules of cultural texts, the fundamental deviation between Music Notes Being Devoid of any Emotions and Record of Music lies not in whether music relates to sorrow or joy but in the destruction and construction of their ethical encodings. That is what has touched upon the genuine difference of their metalanguages. It is a profound cultural semiotic mechanism that could be unraveled from the perspective of semiotics.

4. Conclusion

Record of Music, held up as a major work of classical Chinese art theory, contains elaborate descriptions about how the artist has been touched by external objects and resorted to art creation, and proposed a unique theory of art creation from emotions spurred by objects. In the sense of semiotics, the creation process based on mindbody dualism with embodied perception develops from firstness to thirdness, while the interaction of “qi”, a part of Chinese culture’s prior schematismus, facilitates the welling-up of emotions stirred by external objects. In return, the strong ethical value of the Chinese cultural semiotic system also sways the theory of art creation proposed in the Record of Music, which could be inferred from the dual encoding/decoding principles—the grammar of music and ethical rules. A semiotic interpretation of the Record of Music is therefore of great importance for discovering the deep mechanism and traits of art creation put forward by classical Chinese theories of literature.

———心斋系列

Language and Semiotic Studies2020年2期

Language and Semiotic Studies2020年2期

- Language and Semiotic Studies的其它文章

- A Statistical Approach to Annotation in the English Translation of Chinese Classics: A Case Study of the Four English Versions of Fushengliuji1

- Teaching Indigenous Knowledge System to Revitalize and Maintain Vulnerable Aspects of Indigenous Nigerian Languages’ Vocabulary: The Igbo Language Example

- Deducing the Intonation of Chinese Characters in Suzhou-Zhongzhou Dialect by Its Singing Technique in Kunqu: A New Probe into Ancient Chinese Phonology

- Aspects of Transitivity in Select Social Transformation Discourse in Nigeria

- Umwelt-Semiosis: A Semiotic Perspective on the Dynamicity of Intercultural Communication Process

- L3 French Conceptual Transfer in the Acquisition of L2 English Motion Events among Native Chinese Speakers