A Statistical Approach to Annotation in the English Translation of Chinese Classics: A Case Study of the Four English Versions of Fushengliuji1

Xiangde Meng

Suzhou Vocational University, China

Xiangchun Meng

Soochow University, China

Abstract Annotation in translation is of great value in communicating “the local” to the global readership. Based on our content and function-centered statistics on the 483 notes of the four English versions of Shen Fu’s autobiographical work Fushengliuji, we find that 1) in terms of content, cultural, geographic, historical, and literary references are the most important categories of annotation in the English translation of this work; annotations in the four versions are employed to serve 6 major functions/purposes: to further inform, to facilitate understanding, to avoid misunderstanding, to interpret personally, to cite or allude, and to correct mistakes; 2) no correlation can be established between the use of annotation and the reception of the work per se, but it can reflect the translator’s poise and strategy which ultimately affect the reception of the work; and 3) Lin’s version used relatively few notes and relied heavily on paraphrasing, a practice which leads to better accessibility of his translation and at the same time to the possible sacrifice of some culturally and socially significant elements of the original. Black’s translation used notes sparingly, and she was so creative as to rearrange and edit the original text, revealing her approach of radical “reader-centeredness”. Pratt and Chiang’s version and Sanders’ version used a large number of notes carrying a sinological mission, revealing their respect for the original and their decision to inform and inspire their readers. We argue that cultural translation, whether aided by annotation or not, is predominantly an art about “glocalism” and that both author-centeredness and reader-centeredness can be reconciled, since ultimately they serve the same “communicative” purpose.

Keywords: Fushengliuji, annotation, statistics, English translation of Chinese classics, translation strategy

1. Introduction

Constituting a slight, and often neglected, proportion of compensational or redemptive efforts in translation, and usually falling into the category of paratext, annotation deserves more scholarly inquiry. In fact, owing to language and cultural differences, which pose obstacles in getting information across, annotation is usually a necessary way of compensating for voids. Han Jiaming observed, as many other translators and critics agree, that “Annotation is an important method in translation, especially in translating classics or scholarly works” (Han, 2005, p. 184). Although its significance is recognized by the academic community, systematic research on the application of annotation is far from sufficient. Centered on this issue, scholars in China have addressed three major problems: In what situations is annotation adopted? What functions does it perform in translation? And what principles should be observed in using annotation? For the first question,

Ke Ping noted that annotation is used in three situations: (1) when translating classics or scholarly works, the translator may use annotation to preserve and present the multiple meanings of the original work; (2) when the original expression has allusive meanings, the translator may use annotation to help the reader better understand these allusions; and (3) most often, annotation is used to provide background cultural information for the reader of translated literature. (Han, 2005, p. 184)

For the second question, Han (2005) pointed out that “Almost all Chinese textbooks on translation mention annotation as an important method to clarify difficult points, to provide background information, or to discuss specific allusions” (p. 184). For the third question, Yuan Kejia’s arguments are representative. He summarized six principles to follow, namely, understanding the author’s intent, considering the needs of the readership, using clearly expressed words, using an appropriate number of words, using marked notes, and placing the notes in the right positions (Yuan, 1984, pp. 91-97, our translation).

These inquiries help to illuminate the legitimacy and functionality of notes in translation; however, there is still much to be explored, especially with a more systematic and objective approach. To further address these issues, this paper, based on the four English versions of Shen Fu’s Fushengliuji, is intended to identify and analyze more functions of annotation in translation by virtue of textual, contextualized statistics, to discuss the effectiveness of the notes, and to explore the relationship between the use of annotation and the reception of the translated work. It is hoped that this effort can shed some light on the use of annotation in translation in general and the English translation of Chinese classics in particular.

2. Fushengliuji and Its Translations

Fushengliuji is unique in many senses in the Chinese history of letters. Authored by Shen Fu presumably around the year 1809 when he was 46 years old, it is a phenomenal Chinese classic, well acclaimed both at home and abroad. It is variously regarded as Hongloumeng (A Dream of Red Mansions) in miniature, finished but half lost, or simply unfinished. In a historical light, Jaroslav Průšek, a sinologist and the Czech translator of Fushengliuji (1944), claimed that it was the very first autobiography in Chinese literature (Průšek, 1970, p. 21). According to Shirley M. Black, one of the English-language translators, it is “a literary masterpiece; poetic, romantic, nostalgic and filled with emotion, it recreates a life essentially tragic, which yet held innumerable moments of an almost magical happiness and beauty” (Black, 2012, p. xii). Besides, in their 1972 thesis on this book, Milena Doleželová-Velingerová and Lubomír Doležel argued that “this charming masterpiece of classic Chinese prose is well known to the Western public; it has been translated into several European languages and published in many editions” (Doleželová-Velingerová & Doležel, 1972, p. 138). Undoubtedly, its popularity among Western readers is first and foremost credited to Lin Yutang’s first effort to translate it into the English language as well as to his insight and foresight in recommending to the Western reading public this book and the loving and lovable couple therein. As a matter of fact, as Charles Kwong calculated in 2011, “this short classic has not only earned repeated printings at regular intervals in [the Chinese] mainland and Taiwan, but has inspired 17 translated versions in 14 Asian and European languages since 1935” (Kwong, 2011, pp. 178-179). Among these translations, it is the English versions that are best known to the Western reading public. As of early 2020, four English versions have been produced since 1939 when Lin Yutang’s version was debuted by Shanghai HisFeng/Westwind Press. Black got her version published by Oxford University Press in 1960, Leonard Pratt and Chiang Su-hui theirs by Viking Press in London in 1983, and Graham Sanders his by Hackett Publishing Company in 2011.

The four translated works register approximately 483 notes in total, hence an ideal case for discussions of the legitimacy, functionality, and effectiveness of annotation in the English translation of Chinese classics. They are annotated in different ways, but for similar reasons. Lin’s version uses both footnotes and intext notes marked with brackets, Pratt and Chiang’s employs endnotes, and Sanders’ footnotes. Black’s annotation is different from the others’ in that it uses unmarked intext notes, which are inserted into sentences without brackets or any other markers.

Interestingly, the four translations each offer a translator’s introduction of considerable length. To some extent, the translator’s introduction can be regarded as a unique form of macro-annotation, or possibly better termed, macro implicit annotation as opposed to micro explicit annotation (usually in the form of notes with obvious markers) as we term it, because it shares the same objectives as annotation. The translator intends his or her introduction to defend his or her efforts, to provide necessary background information, to facilitate understanding, to avoid likely misunderstandings, to introduce the translating strategy or methods, etc. Annotation serves almost the same functions. In addition, both introduction and annotation form a nexus of intertextuality with the text. Therefore, the four introductions are also taken into account in the analysis of the statistics.

3. Content-Based Statistics on the Annotations of the Four Versions

It is of special significance to explore in what situations/contexts (related to content), for what purposes (related to function), and in what ways (related to translation strategy, etc.) the four versions are annotated. For one thing, it can shed light on the general use of annotation in translation, and for another, it may help elucidate the nexus between the use of annotation and the reception of the text.

On the basis of content, 9 broad categories are sorted out from the 483 notes in the four English versions. Specifically, language points (mainly about the literal meaning of a Chinese expression), traditions or customs, calligraphy, art, etc. fall into the category of cultural reference; geographical terms and knowledge, the category of geographical reference; historical figures, stories, and events, the category of historical reference; the allusions used but not indicated by Shen Fu while annotated by the translator, the category of allusive reference; literary terms and works mentioned or cited, the category of literary reference; legends, the category of legendary reference; objects, the category of reference of object; the traditional Chinese calendar, the year of a king’s reign and other measurements, the category of reference of measurement; the translator’s individual interpretation added to facilitate readers’ understanding, the category of others. The following is our statistics in this regard.

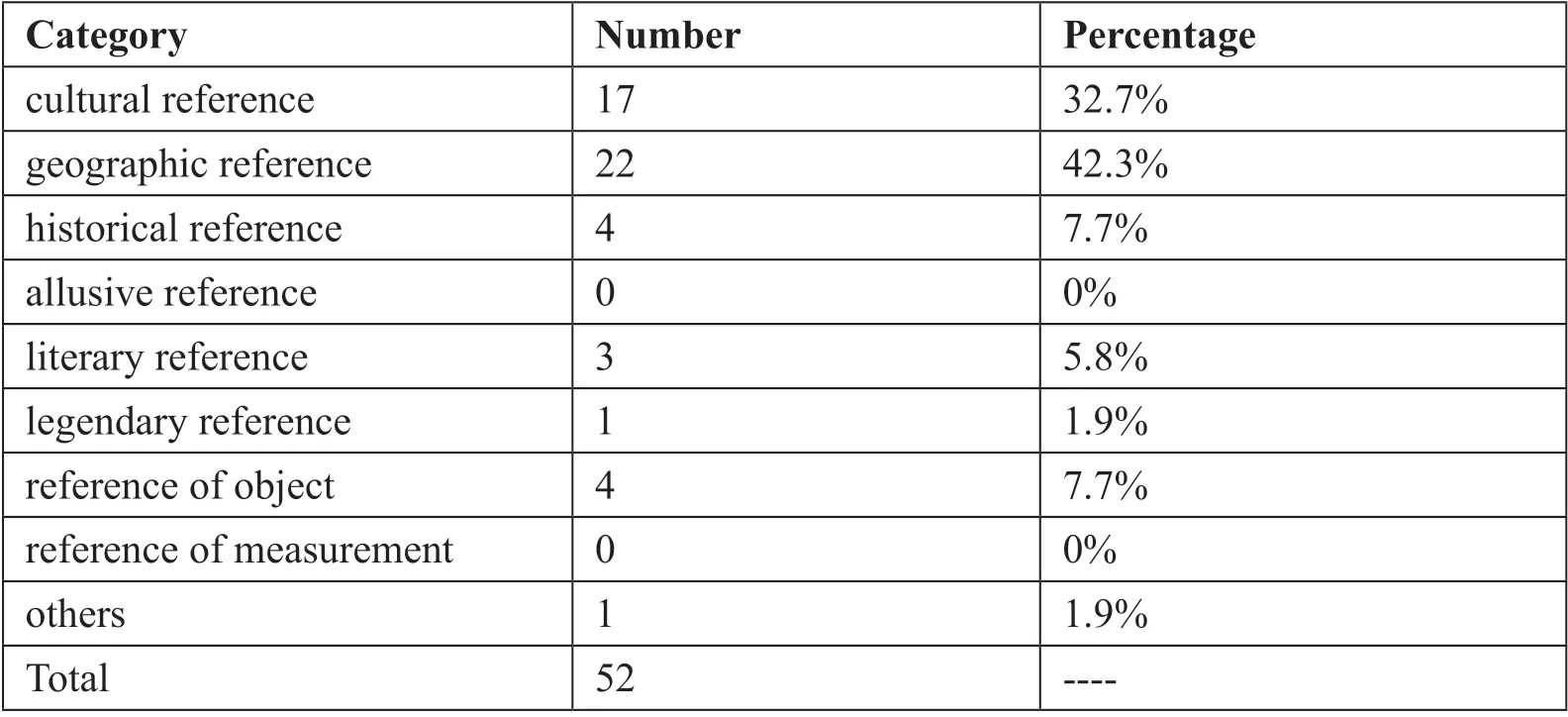

Table 1. Content-based statistics on Lin’s annotations

Lin adopted both footnotes and notes marked with brackets. He used much fewer notes than Pratt and Chiang and Sanders, and only a little more than Black. Table 1 shows that geographical references occupy most of Lin’s annotations, followed by cultural references. The two categories combined account for 75 percent of the total. What’s more, his annotations are relatively succinct. For instance, only 8 items are annotated with 29 words or more, including “竹帘”, “天孙”, “五岳”, “三太太”, “清明”, “江北”, “折桂催花”, and “楹对”. The allusions used by the author are ignored by Lin and the Chinese measurements are directly converted; both are left unannotated. Since geographic nouns in the original text are usually nothing more than archaic though elegant terms for today’s localities, it can be inferred that Lin attached much importance to the cultural elements of the original text in his translation.

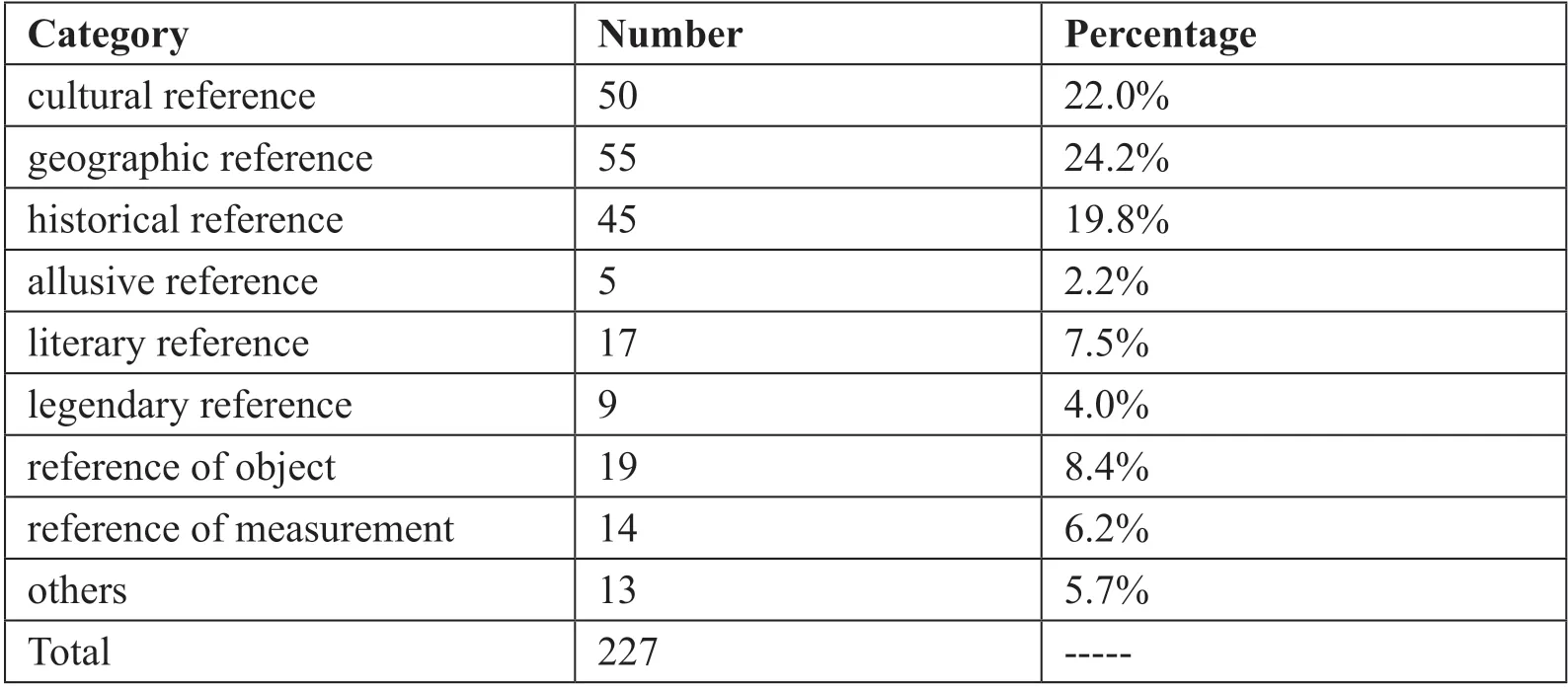

Table 2. Content-based statistics on Black’s annotations

Black’s approach to annotation is different from the others’. In only limited cases are her notes marked with brackets. Most of her notes are in-text ones, skillfully inserted into sentences, without obvious markers. If the English translation is not compared against the Chinese original, this feature may easily go unnoticed. For example, “陈名芸” is translated into “My wife’s name was Yuen, meaning Fragrant Herb” (Black, 2012, p. 3) and “中秋日” into “the Harvest Festival, on the fifteenth day of the eighth month” (p. 23). Both “meaning Fragrant Herb” and “on the fifteenth day of the eighth month” are actually intended to annotate the corresponding Chinese. In addition, the few brackets in her version seem to indicate that they are annotations, but they are actually not (and therefore, they are excluded from the statistics). Black put some parts of the text into brackets for fear that they might sound abrupt in the smooth narrative.

Table 2 shows that cultural references make up the largest share, registering 60 percent of the total. There is no significant gap among geographic, historical, literary, and legendary references as well as object references. Like Lin, cultural elements are her top priority in using annotation.

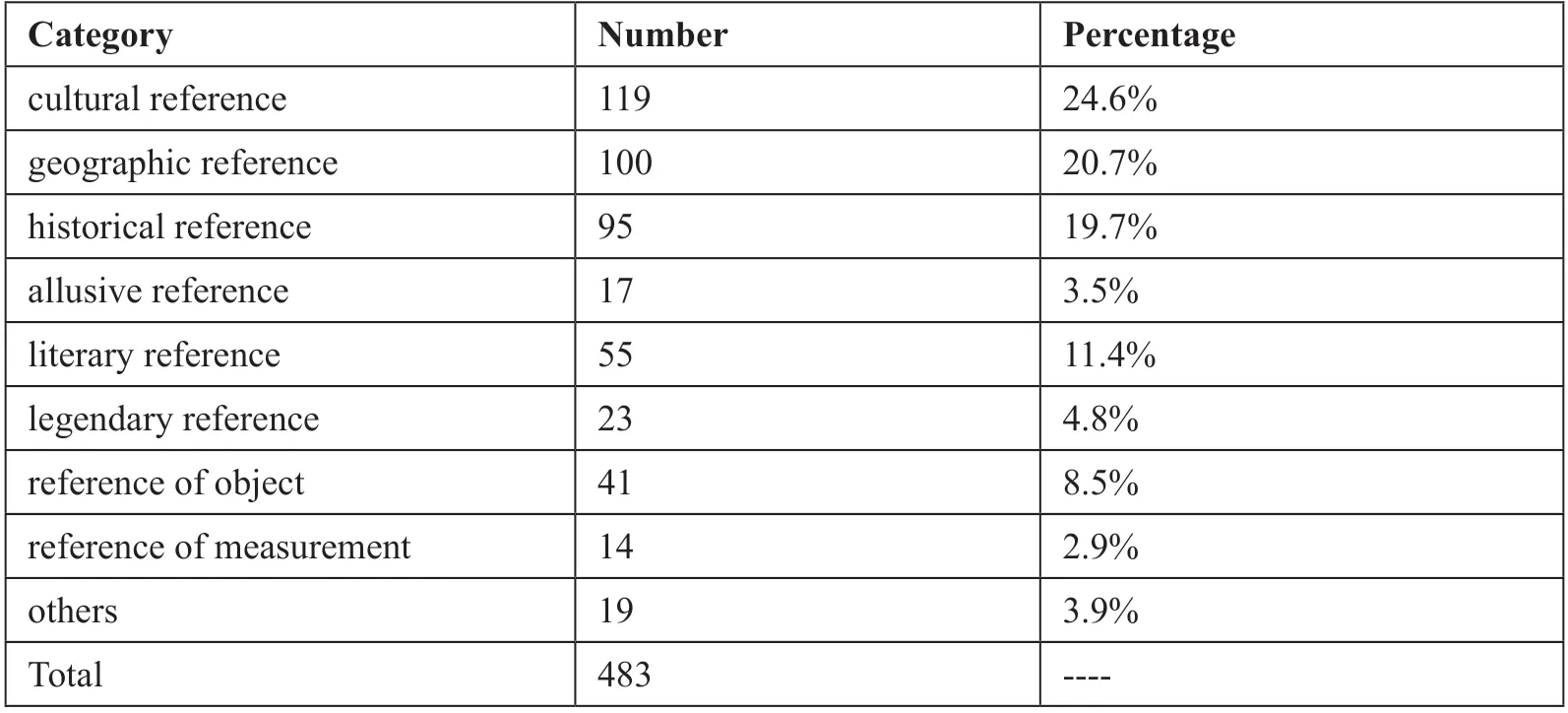

Table 3. Content-based statistics on Pratt and Chiang’s annotations

Pratt and Chiang’s annotations account for nearly half of the 483 notes of the four versions. They are all endnotes, occupying 29 pages out of the 150 in the book, and most of them, when necessary, are dealt with at length. As Table 3 indicates, geographic references, like in Lin’s version, account for the largest percentage, exceeding cultural references which have the second largest percentage. Its historical references are comparatively plentiful. Literary references, object references, references of measurement, and others are relatively evenly dispersed. So are allusive and legendary references.

Table 4. Content-based statistics on Sanders’ annotations

Table 4 shows that, unlike the other three versions, Sanders’ version has the largest percentage of historical references, followed by cultural and then literary references. This means that historical references are Sanders’ major consideration. Sander’s annotations are divided most evenly under the first 7 categories. His notes are notably the most detailed in terms of word count.

Table 5. Integrated statistics of the four annotations above

As is shown in Table 5, in terms of content, cultural, geographic, historical, and literary references are the four most important concerns that all the five translators highlighted in annotation, accounting for 76.4 percent of the total.

Table 6. Statistics on the items annotated in each of the four versions

The data of Table 6 is interestingly significant. The cultural, geographic, historical, and literary references account for 77.7 percent of the total, compared with 76.6 percent in Table 5. However, there are only as few as ten items that are annotated by all the five translators. The items are “芸”, “三太太”, “天孙”, “十年一觉扬帮梦”, “佛手”, “岭南”, “邗江”, “梅逸”, “心经”, and “关圣”. This indicates how significantly different one translator’s choice, interpretation, and rendition of what is culturally meaningful can be from that of another, justifying the role of the translator and the necessity of retranslation.

4. Function-Based Statistics on the Annotations of the Four Versions

According to the functions of annotation, 6 categories are summarized based on the 483 notes. They are “to further inform”, “to facilitate understanding”, “to avoid misunderstanding”, “to interpret personally”, “to cite or allude”, and “to correct mistakes”. The standards for such categorization are as follows:

The notes dealing with cultural, literary, legendary, or any other knowledge or background information, as well as historical figures, go to “to further inform”, which serve only to provide additional information rather than help readers understand. In these cases, readers encounter no trouble understanding the English version even without these annotations. Otherwise, they go to the category of “to facilitate understanding”. For example, Sanders’ annotation to “西厢” is that:

Romance of the Western Chamber (Xixiangji) was an extremely popular Yuan dynasty play attributed to Wang Shifu (ca.1260-1336) that details an illicit love affair between a young woman and a young scholar staying at a Buddhist monastery. It was controversial for its explicit depiction of premarital sex and for its condoning of a freely chosen marriage based on passion rather than familial arrangements. The plot of the play (with a revised happy ending) was drawn from the famous Tang dynasty classical tale “Yingying’s Story” (Yingyingzhuan) by Yuan Zhen (779-831). (Sanders, 2011, p. 5)

His intention was to offer background information about this book, an almost house-hold name to Chinese readers and yet little known to English-language readers. Without the annotation, the target readers, who have no knowledge of this book, may merely know it is a book of love affairs at best, as the word “romance” in the title suggests; with the annotation, however, the readers may be able to associate Yun’s reading of this book with her rebellious, affectionate character (or with other things). Of course, information like this gives readers much leeway to interpret for themselves.

Even though sometimes the same item is annotated in different versions, it does not necessarily belong to the same category; it all depends on the function the note serves. For example, “白居易” is annotated in both Pratt and Chiang’s version and Sanders’; the former is to explain why Yun said Bai Juyi was her first teacher, while the latter is to give more information about this great poet of the Tang dynasty. Thus, the former annotation goes to the category of “to facilitate” and the latter “to further inform”.

Some notes are used to avoid misunderstandings, which are usually incurred by literal translation. For example, “青楼” is translated into “the Blue Pagoda” in Black’s version but is annotated with “the street of prostitutes.” Without the annotation, “the Blue Pagoda” would not be understood by Western readers without a decent knowledge of the Chinese language. Therefore, such annotations serve to avoid the likely misunderstanding and hence fall into the category of “to avoid misunderstanding”. For this same reason, when “佛手” is translated into “the Buddha’s hand citron” with a note (The Buddha’s hand citron is a fragrant fruit shaped like a many-fingered hand that was used to perfume rooms, tea, and clothing and for offerings at Buddhist temples. The Yichang lemon is a hardy, aromatic, inedible yellow-green citrus fruit about the size of a grapefruit.), the annotation is “to further inform”; when it is translated into “Buddha’s Hands”, the annotation (Buddha’s hands are the fruit of a mountainside citrus plant; they are about the same size as, and closely resemble, two hands placed palm to palm in the fashion of Buddhist prayer. They are an aromatic, and are also used to flavor tea—in which case they are considered to be a cure for sore throats—and sweets. The modern version of Shen Fu’s warning about the fruit’s fragility is that it will spoil if touched by someone with oily hands.) is “to avoid misunderstanding”.

Sometimes a translator likes to offer his or her own interpretation of what is implied in the text with a note, which goes to the category of “to interpret personally”. Such practice is similar to “to correct mistakes”. When the translator finds a mistake made by the author or he or she supposes it is a mistake, he or she sometimes marks it with a note. In these two cases, the translator is not necessarily correct and the readers have to make a judgment. In fact, there is only one case of mistake correction in the four English versions, in which both Pratt and Chiang and Sanders pinpointed Shen Fu’s mistake in “每会八人...先拈阄, 得第一者为主考...第二者为誊录...余作举子...十六对中取七言三联” (Lin, 1999, pp. 110-112), and annotated it respectively as “Two entries from each of six candidates ought to have yielded twelve couplets. Shen Fu had little taste for such details, however” (Pratt & Chiang, 2006, p. 125), and “Shen Fu seems to have forgotten that the two people supervising the ‘examination’ would not submit couplets so there should only be twelve couplets in total” (Sanders, 2011, p. 47). As regards to “to interpret personally”, Pratt and Chiang contributed 18 cases among the total 25 (see Table 9). A typical example of this kind from Pratt and Chiang is the annotation of “芸生一女,名青君。时年十四,颇知书,且极贤能,质钗典服,幸赖辛劳” (Lin, 1999, p. 134), which reads “Thus saving her parents the humiliation of visiting the pawnshop themselves” (Pratt & Chiang, 2006, p. 47).

In the original text, Shen Fu sometimes cited straight and explicitly from other works or used implicit allusions. The annotation in this case usually either serves to further inform or to facilitate understanding, but here they are listed under the same category of “to cite or allude”. For example, Shen Fu cited one poetic line “事如春梦了无痕” (Lin, 1999, p. 2) from Su Shi, a renowned Chinese poet of the Song Dynasty. Sanders not only translated it but also annotated it by citing another three lines from the same poem. On another occasion, he annotated “锦囊佳句” (Lin, 1999, p. 6) as:

This is an allusion to the Tang dynasty poet Li He (791-816), who was known for his precocious talent and ghostly imagery. As a boy he would roam about on a donkey in search of poetic inspiration, writing down any lines that came to him and tossing them into an old brocade pouch to finish later. When his mother saw how many poems he was working on, she lamented that his obsession would drive him to “spit out his heart”. He died at the age of twenty-seven. (Sanders, 2011, p. 3)

Therefore, the first example serves “to cite”, while the other “to allude”. They both go to the “to cite or allude” category.

Though “to cite or allude” in a sense serves to provide further information, it is different from the “to further inform” category in that the former either cites directly or alludes to literary works.

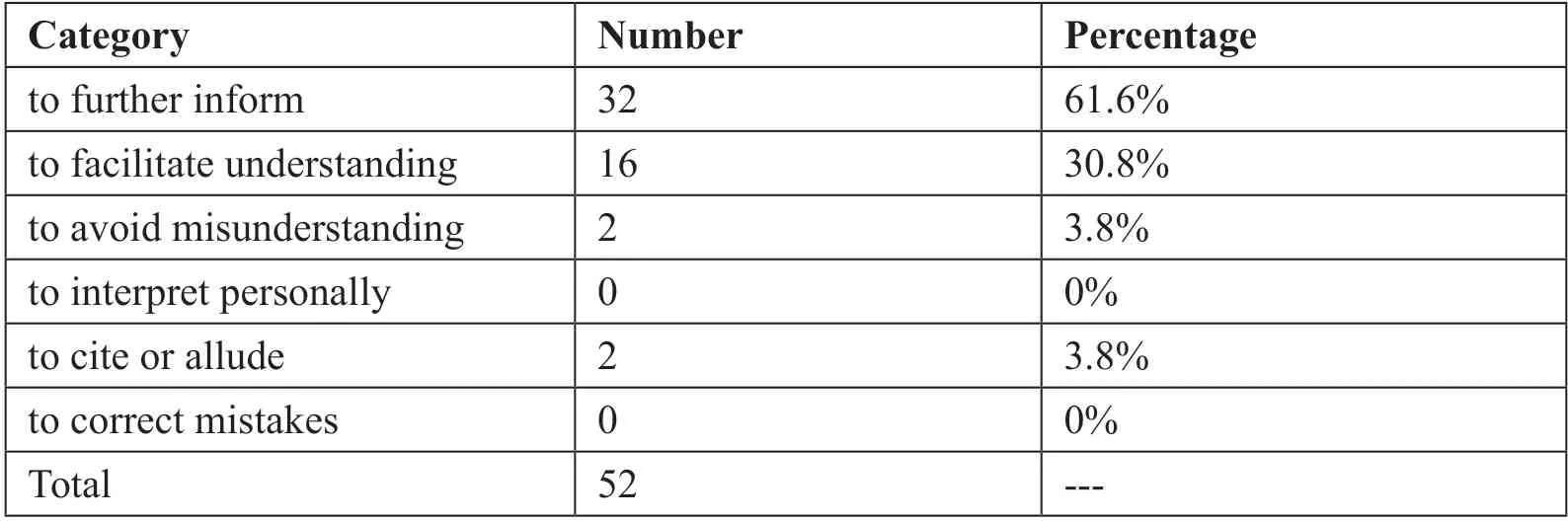

According to the above-mentioned functions of annotation and standards of categorization, we acquired comparative statistics of the notes of the four versions in question (See Tables 7, 8, 9, and 10 as follows).

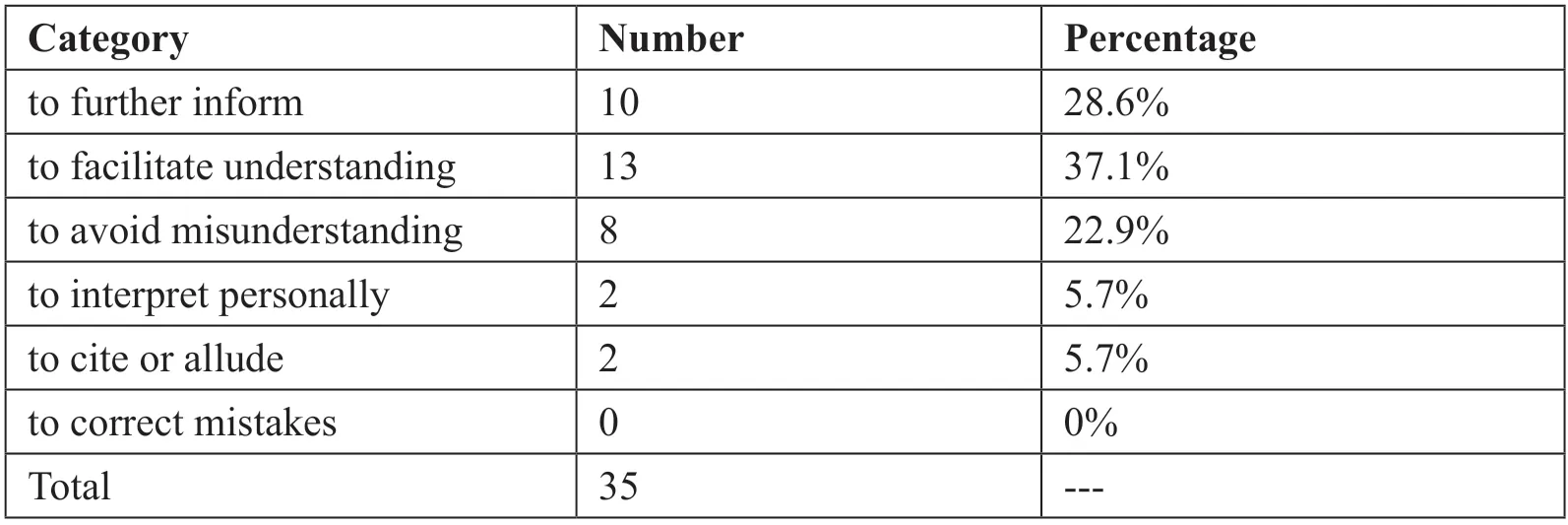

Table 7. Function-based statistics on Lin’s annotations

Table 8. Function-based statistics on Black’s annotations

Table 9. Function-based statistics on Pratt and Chiang’s annotations

Table 10. Function-based statistics on Sanders’ annotations

Table 7 shows that the first two functions, “to further inform” and “to facilitate understanding”, make up 92.4 percent of Lin’s annotations. This indicates that Lin translated with a strong sensitivity to readers’ reception. Table 8 shows that the first three items, “to further inform”, “to facilitate understanding”, and “to avoid misunderstanding”, account for 88.6 percent, with “to facilitate understanding” coming ahead of the other two. In Table 9, the category of “to further inform” makes up the largest share, followed by “to facilitate understanding” and “to avoid misunderstanding” respectively. As in both Lin’s and Black’s versions, the first three categories occupy an overwhelming majority of Pratt and Chiang’s annotations. Table 10 indicates that the category of “to further inform” is also prominent in terms of percentage. But what is noteworthy in Sanders’ annotations in functional terms is that a considerable number of them fall under the category of “to cite and allude”. In fact, Sanders pinpointed most of the allusions used by Shen Fu and annotated them so that the readers are able to learn more about Chinese literature and culture.

If all the annotations, categorized functionally according to the criteria afore mentioned, of the four versions are aggregated and synthesized, a new and probably more revealing statistical table can be formulated as follows:

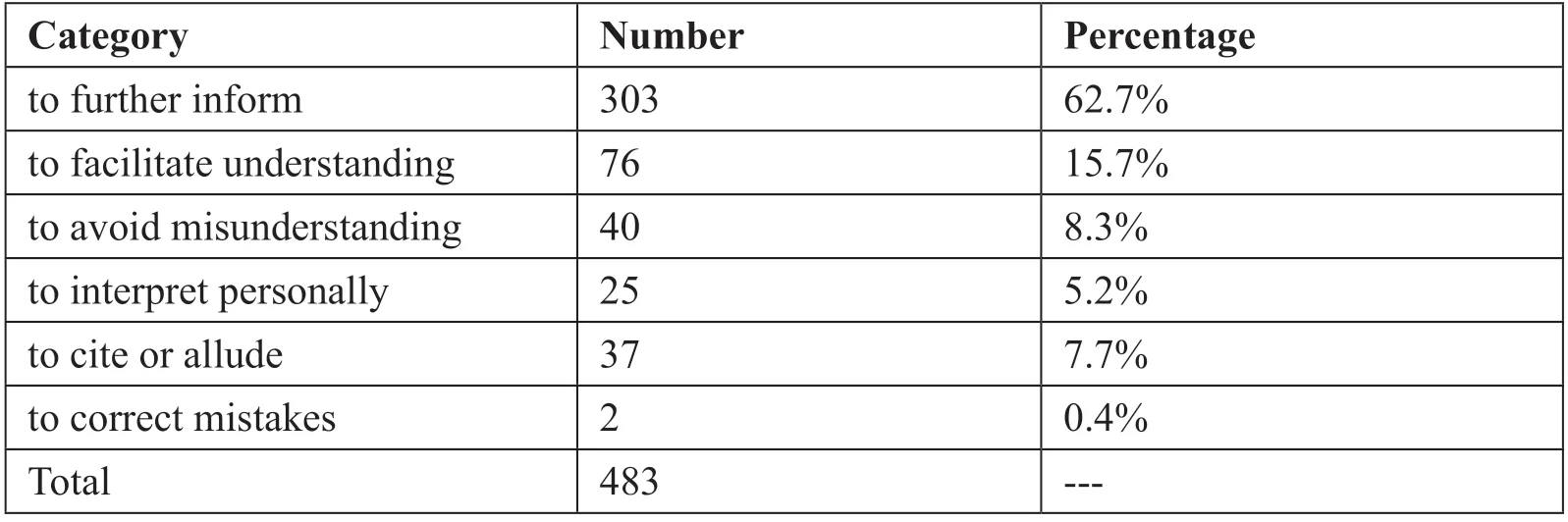

Table 11. Synthesized function-based statistics on the four annotations

This Table clearly shows that the first three, or at least the first two, categories make up the largest share. This general tendency applies to all the four versions. Therefore, it is safe to conclude that in their English translations of Chinese classics, translators tend to use annotations to further inform the target readers, to facilitate readers’ understanding, and to avoid misunderstanding caused by literal translation.

5. Evaluation and Reception of the Annotation in the Four Versions

In their translations of Fushengliuji, all the five translators were caught up in a dilemma. Since translation in general inevitably means cultural compromise and negotiation, they could not have achieved one thing without sacrificing another. In fact, all translators are expected to keep a balance, as graceful as can be, between the two often opposing extremes of author-centeredness and reader-centeredness. The use of annotation per se means a special effort on the translator’s part to be faithful to the author on the one hand, and to make his or her translation accessible on the other. A brief look at the statistics (See Table 12) on the number of notes in each version will generate some understanding of the five translator’s general tendency in the use of annotation and therefore their translation strategies.

Table 12. Number of notes in each version

Lin Yutang chose to paraphrase more with fewer annotations, evidently a readercentered approach. Guan Xingzhong argued in his defense of Lin’s translation strategy that “during Lin’s time, Western readers viewed China as a country of plague and poverty, having little to commend it. Lin knew this and assumed no imposing manners in correcting their biases. This explains why Lin sometimes simplifies the text and has variations to make it easy for target readers” (Guan, 2012, pp. 202-203). “Simplification” here also means Lin’s economical use of annotation; “variation” in this case is almost a synonym for paraphrase. Lin’s means, which surely help to make his translation explicit and therefore more accessible than otherwise, are justified by his end. However, this practice is risky because it may be critiqued as prone to producing clichés in many cases and to losing what is specific to the Chinese language and culture. His successor, Black, however, opted to translate literally while trying to avoid annotations unless forced, so as “to be as meticulous as I could in expressing the exact meaning of the Chinese words” (Black, 2012, p. xiii). Her literal translation without necessary annotations turns out to be what Cyril Birch criticized as “neither English nor…even a fair literal rendering of the original” (Birch, 1961, p. 527). Interestingly, Pratt and Chiang and Sanders endeavored to reconcile or compensate for what is lost in both Lin’s and Black’s approach by employing literal translation with sufficient annotations. In consequence, the readers are interrupted at times to turn to the annotations for help before they possibly exhaust their interest in reading altogether.

It should not be ignored that in most cases the reception of a translated work is usually slow and steady, as is that of a culture. A classic work of value is bound to be reinterpreted and retranslated. Any variation to the previous translation strategies mirrors not only the needs of the readership but also the reception of the translation itself.

The reception of a translated work is subject to many factors such as its value (literariness), social context, ideology, patronage, and poetics. The rub of the question concerning annotation in translation is not “whether”, but “how”. By nature, there is no direct connection between the use of annotation in a translated work and its reception among readers. However, how the translator uses annotation will affect readers’ reception, because the way annotation is used helps to define the translator’s translation strategy.

In Lin’s preface, he stated his purpose by saying “I am translating her story just because it is a story that should be told the world; on the one hand, to propagate her name, and on the other, because in this simple story … I seem to see the essence of a Chinese way of life” (Lin, 1999, pp. 20-21). Lin intended his translation to get the love story and Chinese idle way of life retold to the English-speaking community. With story-telling in focus, paraphrase is a preferable option sine it can minimize the use of intrusive notes and therefore facilitate the narrative. Thus, Lin resorted to the strategy of paraphrase with a minimum of annotations. Guan Xingzhong suggested that Lin adopted instrumental translation instead of documentary translation, the former being source culture-oriented and the latter target culture-oriented (Guan, 2012, pp. 200-203). Cyril Birch criticized Lin’s approach, maintaining that “certainly Lin is not responsible for various touches of the picturesque which may appeal to the general reader but are more likely merely to puzzle him” (Birch, 1961, pp. 526-527). In other words, Birch believed that Lin’s paraphrase actually has often damaged the appeal of the original text. Guan Xingzhong noted that Pratt also criticized Lin’s version in a private letter to the editor, Xu Dongping, complaining that “while reading Lin’s version of Six Chapters of a Floating Life, I noticed … Lin provides regrettably few annotations to explain historical and literary backgrounds, which might be quite useful for English readers” (Guan, 2012, pp. 198-199). It is perhaps for this reason that Pratt and Chiang used the largest number of notes in their translation.

The case of Black then is different. She used annotations sparingly and at the same time rearranged and edited the original. In her introduction, Black declared, “in translating the memoirs I have tried first of all to recreate the subtle emotional atmosphere, at once tragic, passionate, and gay, which is, in my opinion, the outstanding characteristic of Shen Fu’s original…at the same time trying to approximate the feeling of the author’s own way of expressing himself” (Black, 2012, p. xiii). From her statement, it is evident that she emphasized the story itself, and her high-handed manipulation, including rearranging the episodes into a less confusing chronological order, dismissing many episodes as “rather alike” and sections of literary criticism as “of too specialized a nature to be of general interest” (ibid.) and even adding what does not exist at all in the original text, also proves this. For the purpose of story-retelling, Black also omitted many notes that should have been supplied to help readers understand better. Cyril Birch, on the one hand, supported such practice, saying that “Mrs. Black’s omissions are quite justifiable and probably have resulted in a more uniformly enchanting book. The same is true for her policy of rearrangement of episodes into a less confusing chronological order” and “as to the quality of Mrs. Black's translation, this is very satisfying both in its accuracy and in the natural grace and vigor of its English prose” (Birch, 1961, p. 526). On the other hand, Cyril Birch had to admit “in such a case the clichés of Lin's translation would seem in fact preferable to Mrs. Black’s version, which is neither English nor, I believe, even a fair literal rendering of the original” when he cites the two renderings of “始则移东补西”, Black’s being “at first, we tried to make the east fill the west, then to use the left to support the right” (Black, 2012, p. 73) and Lin’s “while at first we managed to make both ends meet, gradually our purse became thinner and thinner” (Lin, 1999, p. 121). So in the end, Cyril Birch suggested that “the reader might appreciate a footnote” and “some notes, indeed, would have added to the book’s value” (Birch, 1961, p. 527). According to P. D. H., “Moreover, even in those parts of her translation which do reflect the Fou-sheng liuchi closely, Mrs. Black’s version is none too accurate. There are several elementary mistakes” (P. D. H., 1961, pp. 177-178). Lionello Lanciotti insisted that Lin’s translation was rather free and Black’s translation had “not the slightest sinological purpose” (Lanciotti, 1961, pp. 80-81). This claim about Black’s translation reveals that Black had neither the necessity nor the responsibility to promote sinological visibility; her sole interest was to retell a good story to her potential readers.

As stated in their introduction, Pratt and Chiang thought Fushengliuji was unique from a Western point of view in that this true love story was set in a traditional Chinese society, whose “small but significant alteration to our perceptions and presumptions which the Six Records can effect…makes it so important a book for Westerners” (Pratt & Chiang, 2006, p. 1). Thus, they noticed the sociological value of this book. To facilitate Western readers’ comprehension, they elaborated on some social phenomena, popular and unique in imperial China but difficult for Westerners to understand without explanations. Therefore, they said, “with the greatest respect for our predecessors … we felt that there was room for a full translation of the Six Records into modern English which would—by the use of extensive but, we hope, not intrusive notes and maps—present to the modern English reader a more complete exposition of the tale Shen Fu told” (Pratt & Chiang, 2006, p. 6). Pratt and Chiang added extensive notes in a full-length translation in order to present a touching narrative set in traditional Chinese society. In other words, their translation carries a sinological purpose. As a reader on Amazon online remarked on October 2, 2019, “the introduction and notes by translators Leonard Pratt and Chiang Su-hui are incredibly valuable … Regarding the notes … they provide helpful cultural and historical detail for those who wish to deepen their understanding of the text” (Quixote, 2019).

Sanders’ approach is in every respect similar to Pratt and Chiang’s. Sanders claimed in the acknowledgements of his book, “I have consulted the work of pervious translators, including Lin Yutang, and Leonard Pratt and Chiang Su-hui in English. I have made every effort to correct previous errors, to provide expanded annotations, and to render Shen Fu’s intimate account into a more colloquial and flowing style of English” (Sanders, 2011, p. vi). Obviously, both Pratt and Sanders were not satisfied with Lin’s scanty annotations, and as a result, Pratt added many more notes to his translation and Sanders not only added notes but corrected, like he said, some of the mistakes Lin made in his translation (annotation included). Meng Xiangchun listed dozens of mistranslations identified in Lin’s version, among which at least 9 are caused by Lin’s misreading of the original text (Meng, 2016, pp. 34-36). Of the 9 mistranslations, Sanders corrected 5 (天孙, 水仙庙, 尧时三祝, 书画铺, 居长而行三) respectively, and mistranslated the other 4 (玉碎香埋, 轻罗小扇, 灵璧石, 酒榼) respectively. However, the mistakes Sanders also made do not undermine the value of his annotations per se in correcting the previous mistakes. Sanders’ efforts won him acclamation from two book reviewers. Michael Gibbs Hill commended his translation, saying “Graham Sanders’s rendition in English of Six Records of a Life Adrift is a joy to read”, and “Sanders has given students, teachers and scholars a new and authoritative translation of Shen Fu’s classic that deserves to be adopted in any course on late imperial or modern Chinese literature, history, and culture”, and what’s more, “the translator provides a clear and accessible introduction, succinctly placing the work in its historical contexts. The footnotes patiently explain the wide range of literary allusions and references to historical events found in Shen Fu’s Records; their clarity and accuracy are a testament to the translator’s erudition and the time that was surely spent ensuring that each note adds to the reader’s understanding of the text” (Hill, 2012, pp. 620-621). Joe Sample held a similar opinion. He said that “Sander’s translation has explanatory footnotes … and the origins and influences of many passages are referenced throughout. The book could be used in any number of courses, in addition to being a required reading for courses on imperial China”. In short, Sander’s translated work has sinological purpose (Sample, 2012, p. 118). After all, Sanders himself is a sinologist.

These five translators’ poise in the sense of inclination toward either authorcenteredness or reader-centeredness or somewhere in between finds interesting expression in their translations of the same sentence as follows:

琢堂又升山左廉访,清风两袖,眷属不能偕行。(Lin, 1999, p. 196)

Lin: …when Chot’ang was again transferred to Shangtung as inspector. As he was an upright official, having made no money from the people and therefore unable to pay the expenses to bring his family there … (ibid., p. 197)

Black: My friend being an honest official, the wind blowing clear through both his sleeves, he could not afford to take his family with him. (Black, 2012, p. 108)

Pratt and Chiang: But by then Cho-tang had again been promoted, this time to be Provincial Judge in Shantso. A light wind could ruffle his sleeves, so his family could not accompany him immediately. (Note: In other words, he had no money to keep in the sleeves of his robe. The implication is that he was an incorrupt, and thus a poor, official) (Pratt & Chiang, 2006, p. 66)

Sanders: …Zhuotang had been promoted yet again to Provincial Surveillance Commissioner of Shandong. Because his two sleeves were filled with only the breeze, Zhuotang could not afford to bring his family with him immediately. (Note: The wide sleeves of official robes were often used as pockets, but the sleeves of an honest official such as Shi Zhuotang were empty of the ill-gotten gains that a corrupt official would enjoy) (Sanders, 2011, p. 81)

There are many examples of this kind reflecting the five translators’ different strategies. Lin tended to paraphrase, even sometimes at the sacrifice of lively expressions of the original; Black was inclined to translate literally; Pratt and Chiang and Sanders tended to translate literally and make compensations with annotation in order to retain and represent the original flavor. The general English-language readers will not encounter difficulty in understanding Lin’s version, nor will they in understanding Pratt and Chiang’s and Sanders’ with the help of annotations. However, they are likely to be puzzled with Black’s translations like “the wind blowing clear through both his sleeves” because these translations, seemingly having a sense of oracularity and leaving much room for indeterminacy and imagination, are aided by no annotation of any form whatsoever.

It is important to note, then, that the use of annotation is not simply an issue of translation or, a step further, cultural communication; it is also very much an issue of cultural identity and ethic. The core issue here is “who is or should be the center? Should the translator move closer to the author, who in this case is the center, or to target readers instead who now are the center? Conventional translation studies hold that author-centeredness and reader-centeredness are of contradictory or opposing nature, since logically there can be only one center here. However, liberation from the yoke of this rigid, if not false, dichotomy may reveal, very rewardingly, that in translation, both author-centeredness and reader-centeredness can be compatible and united since they both serve a “communicative” purpose: author-centeredness helps to enrich linguistic and literary possibilities and experiences in the target language while the latter helps to ease readers’ burden in reading the translated work which, in turn, means new inputs. Annotation in translation is derived from cross-cultural differences, and the use of it can enrich the linguistic and cultural ecology of the target culture, all serving to bridge communicative gaps between cultures. In this sense, it can be argued that translation, whether in the sense of activity, process, or effect, is predominantly an art about “glocalism”, a kind of reconciliation between, and mutual transformation of, the local and the global in cultural terms and beyond, and this reconciliation and mutual transformation may eventually help to shape a universal cultural landscape pointing to the possibility of a community of shared future.

6. Conclusion

Annotation in translation, be it macro implicit annotation or micro explicit annotation, which is usually in the form of notes with obvious markers, is a significant way of compensating for and representing the culturally and socially meaningful elements of the original text. According to our statistics, we find that among the four English versions of Shen Fu’s Fushengliuji, Black used the fewest notes, totaling 35, followed, in an incremental fashion, by Lin’s version (52), Sanders’ version (169), and Pratt and Chiang’s version (227). All the 483 notes of the four versions can fall into different categories in terms of content and function, respectively. In terms of content, cultural, geographic, historical, and literary references are the most important categories of annotation in the English translation of Fushengliuji, and this may shed light on the use of annotation in the English translation of Chinese classics in general. The 483 notes are used to serve 6 major functions or purposes: to further inform, to facilitate understanding, to avoid misunderstanding, to interpret personally, to cite or allude, and to correct mistakes. No intrinsic link can be established between the use of annotation and the reception of the work since the reception of any particular work inevitably involves a considerable number of factors, say, the original text per se, the social context, ideology, poetics, patronage, translation strategy, communicative purpose, the translator’s identity and subjectivity, etc., but how the translator understands and uses annotation may reflect his or her cultural poise and translation strategy, which will eventually affect the reception of the work in translation. When the four English versions are juxtaposed, we may find that Lin’s version used notes economically and inclined to paraphrase; this practice generates easier accessibility on the part of target readers but in the meantime may sacrifice some significant cultural, historical, and social elements of the original text. Black adopted a similar practice in the use of annotation, but she was creatively courageous as to rearrange and edit the original text in order to reproduce a touching romantic narrative, revealing her approach of radical reader-centeredness. Pratt and Chiang’s and Sanders’ versions used plentiful notes out of their essentially sinological consideration, showing their respect for the original on the one hand and their decision to inform and inspire readers on the other. All the translators of Fushengliuji are justified in their decisions on their particular translation strategies. In many senses, translation in general and the English translation of Chinese classics in particular is predominantly an art about “glocalism”, both authorcenteredness and reader-centeredness can be reconciled since they ultimately serve the same “communicative” purpose.

Note

1 This research is sponsored by the “Overseas Reception of Suzhou Local Culture” fund (No. 2019SJA1330) and the Jiangsu Social Sciences and Humanities Fund (No. 18WWD005).

Language and Semiotic Studies2020年2期

Language and Semiotic Studies2020年2期

- Language and Semiotic Studies的其它文章

- Teaching Indigenous Knowledge System to Revitalize and Maintain Vulnerable Aspects of Indigenous Nigerian Languages’ Vocabulary: The Igbo Language Example

- Deducing the Intonation of Chinese Characters in Suzhou-Zhongzhou Dialect by Its Singing Technique in Kunqu: A New Probe into Ancient Chinese Phonology

- Aspects of Transitivity in Select Social Transformation Discourse in Nigeria

- Towards Semiotics of Art in Record of Music

- Umwelt-Semiosis: A Semiotic Perspective on the Dynamicity of Intercultural Communication Process

- L3 French Conceptual Transfer in the Acquisition of L2 English Motion Events among Native Chinese Speakers