Umwelt-Semiosis: A Semiotic Perspective on the Dynamicity of Intercultural Communication Process

Juming Shen

Xi’an Jiaotong Liverpool University, China

Yu Sheng

Soochow University, China

Xingchen Shen

University of Liverpool, UK

Xi’an Jiaotong Liverpool University, China

Abstract

Keywords: intercultural communication, umwelt, semiosis, semiotics

1. Introduction and Background

Semiotics has shed much light on both communication studies and cultural studies, and has thus informed academic investigations in intercultural communication (IC), an area increasingly concerned in scholarly research. In our previous semiotic probes into this area, we strove to interpret the process of intercultural communication from a semiotic perspective (Shen, 2010). Later, in our case study examining how visual signs in EFL textbooks might assist learners to develop awareness of cultural differences, we also tried to reveal how an individual’s cultural knowledge and awareness can be affected through intercultural communication (Shen & Su, 2015). Both studies integrated a number of semiotic perspectives such as cultural semiotics by Lotman (1990), semiotic definition of communication by Umberto Eco (1976) as well as several semiotic conceptualizations derived from Charles Sanders Peirce.

We developed a model of the intercultural communication process (Figure 1) based on an analysis of all the possible elements involved in the process by integrating several communication models such as Shannon-Weaver’s Mathematical Model of Communication, Schramm’s Model of Communication, Jakobson’s Communication Model and H. G. Alexander’s Model of Human Communication (see Shen, 2010). The analysis was conducted following a range of semiotic perspectives among which Peirce’s perception of sign as a triadic relation (e.g. Peirce, 1960) and Juri Lotman’s (1990) conceptualization of semiosphere derived from his cultural semiotics were the most significant references.

Figure 1. Semiotic Model of Intercultural Communication (Shen, 2010)

In this model, we supposed the similarity between the “objects” of the source and the receiver as the measurement of the effectiveness or the “success” of an intercultural communication act. That is, we hypothesized that in the context of intercultural communication, the source and the receiver had different cultural backgrounds and thus different ways of interpreting a same message; if the message were interpreted to stand for the same thing or meaning, the communication could be seen as effective or successful. Moreover, we acknowledged that it is the collaboration and mutual-affection between a variety of elements such as semiosphere, representamen, and interpretant that would together determine the effectiveness and success of intercultural communication (see more in Shen, 2010). In addition, we emphasized the correlative link between semiosis (the triadic sign-relation) and semiosphere which indicates that a communicator’s cultural background embeds the norms of behavior. This viewpoint was derived from Lotman’s (2005) elaboration that semiosis exists and operates within semiosphere as a systematic and multi-levelled structure of culture. We will further our discussion on this point in this paper.

Nevertheless, our model, like many other studies on intercultural communication, presupposed that communicators have different cultural backgrounds since intercultural communication as a discipline originates from the problems caused by cultural differences and it is typically understood as “communication between people whose cultural perceptions and symbol systems are distinct enough to alter the communication event” (Samovar, Porter, McDaniel, & Roy, 2017, p. 48), which is an anthropological viewpoint and may cause some confusion beyond the field itself, as we will explain later. A consequence of such conceptualization of intercultural communication is that a majority of research on IC has been based on the presupposition, or hypothesis, that the communicators have different cultural backgrounds or different cultural “perceptions and symbols” (e.g. Chen & Starosta, 2007; Fantini, 1995; Jandt, 1998; Rogers, Hart, & Miike, 2002; Samovar et al., 2017). Meanwhile, it has been broadly accepted that both culture and communication are dynamic and can be shaped, transformed or transmitted (e.g. Jandt, 1998; Samovar et al., 2017; Wood, 1994), based on which we can well contend that the so-called “gap” between the communicators is also dynamic, transformable, shapeable, and thus bridgeable. In other words, intercultural communication is itself a dynamic process that can affect the communicators in terms of their cultural perceptions or manners of thinking and behaving rather than simply a result of their different cultural backgrounds.

In this paper, we will explore the dynamicity of intercultural communication in a detailed manner by examining the umwelt-semiosis of the subjects involved in the communication as individuals differ from and relate to one another. We will start by discussing in depth about how intercultural communication is rendered dynamic, and thus indicate the feasibility to investigate such dynamicity within the theoretical framework of semiotics. Afterwards, we will elaborate on the relevant semiotic perspectives with a focus on umwelt, a biosemiotic concept that shares a similar paradigm with the concept of semiosphere and has been aligned in edusemiotics as capable of demystifying the process of how human perceptions can be affected or shaped (see, e.g. Semetsky, 2015; Semetsky & Stables, 2014; Stables, 2018). With the toolkit of semiotics, we will explain in detail the dynamic process through which communicators’ culturally embedded manners of thinking and behaving can affect and be affected by the process of intercultural communication.

2. The Dynamicity of Culture and Communication

The earliest communication between people from different cultures could be traced to the exchanges made by ancient figures like Marco Polo (1254-1324). However, the study of communication between different cultures as an academic discipline was not established until the 1950s when Edward T. Hall (1914-2009), an American anthropologist, published his first book, The Silent Language, as the milestone of studies in this field (Rogers et al., 2002). Since Hall’s inauguration, the research on this topic has followed two tracks in general, namely the contrastive analysis of the differences in communication between different cultures, which is largely an anthropological perspective and usually termed cross-cultural communication (CC), and the analysis of dynamic process of the communication, often termed intercultural communication (IC) (Hu & Jia, 2007). While cross-cultural communication focuses on static comparison of value systems, cultural perceptions, conversations, and manners, intercultural communication studies aim to explain the more dynamic processes such as how to avoid uncertainty, how to establish identity and how to deal with cultural conflicts (Chen & Starosta, 2007; Jandt, 1998).

However, although the differentiation between CC and IC demonstrates that cultural systems and communicative systems both affect the mutual understanding between communicators from different cultures, it by no means indicates or implies that the two fields could or should be separated in either academic inquiries or in practical contexts of communication. The foremost reason is, as Hall put it, “culture is communication and communication is culture” (Hall, 1976, p. 14); that is, communication and culture are interrelated and mutually reliant. Culture is created, changed, transmitted, and acquired through communication while communication practices are also largely created, transformed, and transmitted by culture (W. C. Wang, Lee, & Chu, 2011).

Moreover, as we have previously argued based on some widely recognized definitions of culture (e.g. Jandt, 1998, p. 8; Samovar et al., 2017, p. 57), paradigmatically speaking, culture as a term is descriptive rather than prescriptive (Shen, 2010). That is, cultures or cultural differences can be referred as to descriptions of the commonalities of groups defined by certain principles such as religion (Buddhist culture, Christian culture, Islamic culture, etc.), geography (American culture, Chinese culture, African culture, etc.), or history (ancient culture, modern culture, contemporary culture, etc.), or more than one principle (e.g. Ancient Chinese Culture; Western Religious Culture). Although a “group culture” does exert a great impact on the growth and development of individuals belonging to it, or at least it is an important factor that shapes its members’ identity (Pratt, 2005), people in a particular cultural group are still “members who consciously identify themselves with that group … the identification with and perceived acceptance into a group that has a shared system of symbols and meanings as well as norms for conduct” (Jandt, 1998, p. 6). In other words, culture is a metaphysical concept based on the accumulative construction and contribution of a group of people, rather than a set of established norms and beliefs for the present (Samovar et al., 2017, p. 57). To put it simply, culture in its first sense should be referred to as a summary of the manners in which a particular group of people act or think, though such manners do impact or shape the newcomers joining the group such as children or people from other cultures.

Such explanation not only acknowledges individuals’ contribution and determinative role in the construction of cultures, but also highlights the feature of culture as being dynamic and ever-changing. That is, even within a certain group, its members may keep shaping or transforming their manners of behavior, making culture always dynamic (Samovar et al., 2017). Such dynamicity, considering its correlation with communication, is also supported by a widely accepted definition of communication as “a dynamic, systematic process in which meanings are created and reflected in human interaction with symbols” (Wood, 1994, p. 28). In other words, human beings keep creating, shaping, transforming, and transmitting culture through communication which in return is also constantly being created, shaped and transformed.

The dynamicity of culture and communication, nevertheless, may problematize the definition of intercultural communication that we have cited in the first section of this paper. To be specific, as both culture and communication are dynamic, how can we define or measure the extent of “enough” as in “communication between people whose cultural perceptions and symbol systems are distinct enough to alter the communication event” (Samovar et al., 2017, p. 48)? In our opinion, the socalled “cultural difference” cannot be referred to as a matter of degree but should be considered rather as a matter of by what the communicators in an intercultural context differ so that the communication event may be altered and differentiated from that in an intracultural context.

This viewpoint aligns with a prevailing concern in studies of intercultural communication that the “cultural identity” of the communicators upon which cultural differences are assumed to impact is increasingly difficult to define within the context of globalization (e.g. Foroudi, Marvi, & Kizgin, 2020; Galyapina, Lebedeva, & Lepshokova, 2020; Greischel, Noack, & Neyer, 2019; Liu & Kramer, 2019; Shen & Gao, 2015). In other words, along with the booming interaction between different countries, regions, religions or groups that can be defined by particular principles as we explained above, the members within a particular group may no longer be the bearers of the specific features that have been used to differentiate the group from other groups. For example, the communication between China and the West was often nicknamed as “Tea-Coffee” communication as tea and coffee stand for the most typical drinks in each culture. Nevertheless, according to a report, an increasing number of Chinese people, especially the younger group, tend to replace tea with coffee for daily drink, or at least accept both as alternatives (Wang, 2018). Hence, it may no longer be appropriate to assume that tea is always preferred by a Chinese. With such changes taking place at all levels from daily activities as “superficial” or “popular” culture to belief and values as “deep culture”, presuming how an individual tends to think or behave based on his/her “cultural background” becomes increasingly difficult and risky. More importantly, such a viewpoint, though being a bit hypothetical, indicates that it is not the “cultural backgrounds” that determine the effectiveness and success of intercultural communication; instead, it is the specific manner in which communicators conduct the communication act that would be the most decisive factor.

Therefore, the most valuable and prospective method of furthering the investigation into intercultural communication may be the exploration of the detailed manners by which communicators conduct communication. Furthermore, as both culture and communication are dynamic, we can well contend that the communicative manners are also dynamic and thus shapeable and transformable. Hence, the questions for us can be coded as how do communicators conduct communication in an intercultural context? And more importantly, how can the conduction be affected dynamically? Or, in simple words, what may actually happen to one's manners of thinking and acting when one is confronted with different manners of thinking and acting? To answer the questions, we will adopt a semiotic framework centering on the concepts of umwelt by Jakob von Uexküll and semiosis by Charles Sanders Peirce as a tool of analytics in this study.

3. The Umwelt-Semiosis Framework

In our semiotic model of intercultural communication (Figure 1), the interaction and mutual affection between intercultural communication and the manners of the communicators were illustrated by the description of the link between semiosis and the semiosphere, and that link was further explored in another study (Shen & Su, 2015) when we were reflecting on how the semiosis process, which is dynamic and ever-happening, could affect the semiosphere. Our case study of photographic illustrations as visual signs indicated that the interpretation of the signs could bring up new interpretants and objects, and thus affect the communicators’ semiospheres. We built this argument on Peirce’s (CP 2.235) explanation that representamen is infinity of further interpretant which may proceed as well as precede from any representamen given; and such a process may produce new objects too. Hence, the semiosphere of the learners may expand through the infinite conduct of the semiosis, which would then affect individuals’ linguistic and cultural backgrounds. We used the following model (Figure 2) to illustrate such processes (Shen & Su, 2015).

Figure 2. Semiosis and semiosphere (Shen & Su, 2015)

Nevertheless, we did not further investigate how such interaction and interaffection might take place. In this section, we will elaborate on concept of umwelt proposed by Jakob von Uexküll (Brentari, 2011; Deely, 2004), which is inter-related with semiosis and shares a similar paradigm with that of semiosphere (M. Lotman, 2002), so as to illustrate the interaction and inter-affection and thus to reveal how the dynamic process of intercultural communication may affect the communicators regarding their manners of thinking and behaving.

The concept of umwelt was developed by the Estonian-German scientist Jacob von Uexküll in the early twentieth century when he coined it in his book Umwelt und Innenwelt der Tiere in 1909. Uexküll was first introduced into semiotics by Sebeok, a classical semiotician largely inspired by Peirce, in his book The Sign & Its Masters (1979). Since then, Uexküll’s work, especially his concept of umwelt, has been broadly received and developed in semiotic studies. Contributors to the development and application of umwelt include such prominent semioticians as Sebeok (1979), Kalevi Kull (e.g. 1998, 2004), John Deely (e.g. 2001, 2004), Riin Mangus (e.g. 2008, 2011, 2012), and Morten Tønnessen (e.g. 2009, 2011).

Defined as “the world around an animal, conceived by it as a perceiving and operating subject, i.e., the subjective world as contrasted with the environment” (T. A. Sebeok & Danesi, 1994, p. 1146), the term “umwelt” has a denotation of “surrounding world” and a semantic connotation from Uexküll’s investigation about how living organisms perceive the environment and how such perceptions may affect their behaviors (Brentari, 2011). Basically, Uexküll started his analysis when he noticed that animals of different levels including unicellulars at low levels and hominids at higher levels, are all capable of discerning meanings from environmental indicators as they are all living systems endowed with Ich-Ton, or “ego-quality” as a property of subjectivity (Wąsik, 2018). Such analysis was largely originated from Uexküll’s dissatisfaction with the biological studies of his time as he criticized the then prevalent viewpoint that all non-human animals were treated as machine-like objects. For Uexküll, all simple and complex animals should be understood as subjects which constitute and make the world they live in, or their umwelt, meaningful through their perceptions and actions (Schroer, 2019).

Uexküll’s analysis has been regarded as a trial to solve the classic conundrum about how humans or animals perceive the world. His research has been considered pioneering in the exploration of the meaning-making both in and beyond the human societal realm and has influenced researchers in fields ranging from ethology to anthropology (Schroer, 2019). In semiotics, including biosemiotics and beyond, Uexküll’s work has been offering substantial enlightenment (e.g. Chávez Barreto, 2019; Deely, 2001, 2004; Schroer, 2019; Wąsik, 2018), as Sebeok (1979) acknowledged Uexküll to be a “cryptosemiotician” and as Deely (2004) put it:

…basic principles which establish the ground-concepts and guide-concepts for their ongoing research. These principles, in turn, come to be recognized in the first place through the work of pioneers in the field, workers commonly unrecognized or not fully recognized in their own day, but whose work later becomes foundational as the community of inquirers matures and ‘lays claim to its own’. As semiotics has matured, the work of Jakob von Uexküll in establishing the concept of Umwelt has proven to be just such a pioneering accomplishment for the doctrine of signs… (p. 11)

Yet before elaborating on the impact that umwelt brings about to studies of semiotics, we would like to introduce a bit more about the umwelt by means of two metaphors that Uexküll used as explanation to the concept, namely the soap bubble metaphor and the music score metaphor.

Uexküll used the metaphor of the soap bubble to explain the invisible worlds of animal subjects. According to Uexküll ([1934]2010), all animals (including the humans) can be seen as immersed in their own bubbles, through which they perceive the world which is mediated by signs in their own realm of time and space. Furthermore, while an animal is encapsulated in its own bubble, it would not be able to know anything about how other animals perceive their worlds directly through its own body. This also applies to a human being as he/she is not able to know how another human perceives the world and can only construct his/her subjective world in the “mind’s eye” (von Uexküll, [1934]2010, p. 42). Yet such construction is possible through observations of their behaviors or activities and via imagination that infers how the individual umwelt might look like. Hence, the bubble metaphor in fact on the one hand represents the limited horizon of each organism’s world as the world of a subject is determined by the subject’s abilities and potentials to experience, and on the other hand demonstrates that an animal or a human could understand the subjective world of another living being only in an indirect manner (Schroer, 2019).

Contrary to the soap bubble metaphor that emphasizes the limitation of an animal’s or a human’s capability of perceiving other’s subject world, Uexküll’s music metaphor, which compares the relationship between a subject and its subjective world as melodies in polyphonic musical compositions, focuses on the creativity and interconnection of the organisms, like that part of the natural musical harmony (Schroer, 2019). Or, in Uexküll’s own words, “We see here [in pairs] the first comprehensive musical laws of nature. All living beings have their origin in a duet” (von Uexküll, 2001, p. 118). With the interest in how organisms express themselves through interrelations, Uexküll created the possibility of regarding subjects as “beings-in-the-making” through the activities that they are involved in instead of seeing them simply as entities fabricated prior to the relations (Schroer, 2019).

Putting the soap bubble metaphor and the music metaphor together, Uexküll shows to us how subjects exist in relation with and interact with each other, which together make up the worlds for every living being. In Uexküll’s words, he was showing “how the subject and the object are dovetailed into one another, to constitute a systematic whole” (von Uexküll, [1957]1992, p. 324). Furthermore, Uexküll used the term Funktionskreis, or “functional cycle” as the basic unit of the mechanism that constructs the umwelt. According to Uexküll, such functional cycle is “a general schema that underlies the relationship between any animal and the world” and the base of “the unity that every animal establishes with its world” (Brentari, 2011, p. 100; von Uexküll, 1921, p. 45 as cited in). In other words, for Uexküll, a living being perceives its umwelt through its action and reaction within it and the consequence of such circularity of action and reaction is the continuous affecting, shaping and reshaping of its world and its perceptual systems. Uexküll used two terms, “receptor” and “effector” to illustrate such processes:

Figuratively speaking, every animal grasps its object with two arms of a forceps, receptor and effector. With the one it invests the object with a receptor cue or perceptual meaning, with the other, an effector cue or operational meaning. But since all of the traits of an object are structurally interconnected, the traits given operational meaning must affect those bearing perceptual meaning through the object, and so change the object itself. (von Uexküll, [1957]1992, p. 324)

Following Jesper Hoffmeyer’s (1996) book on the approach to biosemiotics and the explanation of umwelt as “what defines the spectrum of positions that an animal can occupy in the biological sphere, its semiotic niche” (p. 140), Kull (1998) stated that umwelt could be understood as the semiotic world of an organism. Based on Uexküll’s bubble metaphor and music metaphor, such “semiotic world of an organism”, as we can identify, refers to at least two perspectives of semiotics that can be linked with umwelt.

First, the “functional cycle” by Uexküll accords with the concept of semiosis by Peirce in their common recognition that a subject participates in the experiential process by perceiving cues and responding to the cues accordingly. For Peirce, semiosis refers to the interaction between the sign (or representamen), the object, and the interpretant:

A sign... is something which stands to somebody for something in some respect or capacity. It addresses somebody, that is, creates in the mind of that person an equivalent sign, or perhaps a more developed sign. That sign which it creates I call the interpretant of the first sign. The sign stands for something, its object. It stands for that object, not in all respects, but in reference to a sort of idea, which I have sometimes called “the ground of the representamen”. (CP 2.228)

Although for Uexküll, he emphasized that biologically the cues are perceived as sensations by perceptual organs. Hence, such cues, be they formal or material, can be identified with what Charles Sanders Peirce termed as representamen while the process of perceiving may well be explained by interpretation, or interpretant, through which a cue may stand for an object. Based on such a semiosis process, a subject, or interpreter would generate further representamen as responses, or “effector cues”.

In addition to semiosis, umwelt is also conceptually explainable by semiosphere, a concept raised by Juri Lotman (2005) because they proceeded from similar paradigms, as stated by Mihhail Lotman (2002), the son of Juri Lotman. For Juri Lotman, semiosphere was not totally dependent on the preceptor and effector of subjects. Although he stated that “semiosphere is the semiotic space, outside of which semiosis cannot exist”, the example of language Lotman used to illustrate such a relation seems to be highlighting the independence of semiosphere: “The ensemble of semiotic formations functionally precedes the singular isolated language and becomes a condition for the existence of the latter. Without the semiosphere, language not only does not function, it does not exist” (J. M. Lotman, 2005, p. 205). Hence, when expounding on umwelt, Hoffmeyer (1996) expressed his concerns, “the semiosphere imposes limitations on the Umwelt of its resident populations in the sense that, to hold its own in the semiosphere, a population must occupy a ‘semiotic niche’” (p. 59). Nevertheless, in Kull’s viewpoint, semiosphere is “the set of all interconnected Umwelts” (1998, p. 305) and “entirely created by the organisms’ Umwelts”:

Organisms are themselves creating signs, which become the constituent parts of the semiosphere. This is not an adaptation to environment, but the creation of a new environment. I can see here the possibility for a more positive interpretation of Hoffmeyer’s statement—namely, the concept of ecological niche as it is traditionally used in biology, can be essentially developed according to the semiotic understanding of the processes which are responsible for the building of Umwelt. (p. 306)

Such argument by Kull aligns with Thure von Uexküll, son of Jakob von Uexküll, who stated that every organism responds only to meaningful signs and not to casual impulses (1992, p. 285). In other words, umwelt is a part of semiosphere and it is in this part that semiosis takes place and the framework of semiosis and semiosphere (Figure 2) can be further developed into an umwelt-semiosis framework as follows (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Umwelt-semiosis framework

The elaborations above bring about substantial enlightenment to our understanding and analysis of intercultural communication. In our semiotic model of IC (Figure 1), the source’s and receiver’s semiospheres refer to their respective cultural backgrounds. In the analysis of the relation between semiosis and semiosphere (Figure 2), we further explained that semiosphere can be affected and shaped through semiosis. According to the above discussion on umwelt, semiosis and semiosphere, we can contend that it is the umwelt as the effecting part of the semiosphere that interacts with semiosis which involves perception and operation as interpretation; meanwhile, the semiosis process affects and is affected by the effecting umwelt and thus the semiosphere. In the following section, we will apply this umwelt-semiosis framework in analyzing how communicators’ culturally specific manners of thinking and behaving, or their umwelt, can be affected by intercultural communication which is realized through continuous semiosis.

4. The Umwelt-Semiosis of Intercultural Communication Process

As we have discussed above, when an individual is perceiving or operating in a particular environment, it is in fact a process of interaction between semiosis and the umwelt, which are also mutually affective. Hence, in intercultural communication, it is the interacting processes that the source and the receiver undergo respectively that affect the communication. In Section 2, we have discussed that it is the specific manners of communicating that would determine the effectiveness or “success” of intercultural communication. According to the umwelt-semiosis framework we have established, the specific manners of thinking and behaving of the individuals in an intercultural communication context can be considered as referring to the specific umwelt-semiosis of the communicators and termed “functioning cultural background” or “working cultural background”. Hence, to elaborate on the dynamic process of intercultural communication means to find out how the umwelt-semiosis of the communicators as individual subjects differ as well as interrelate with each other. This involves detailed examination of how each of the communicators’ umwelt and semiosis are mutually affective as well as how their umwelt-semiosis are mutually affective as well.

Our semiotic model of intercultural communication illustrated two detailed phases, namely the source (a living subject) creating the message (representamen) and the receiver (another living subject) perceiving the message, both realized through semiosis. We should now expound on how the semiosis may affect the umwelt of the communicators. First, let’s focus on the source’s umwelt-semiosis. As has been discussed in the previous section, a subject interacts with his/her umwelt via their “receptor” and “effector”. That is, a subject’s perception is a priori to the effector cues to be used to affect his/her subjective world. Therefore, for a “source” in intercultural communication, the message, or the effector cue, must have been created based on his/her perceptions, while such perceptions as a result from a perceiving process must have already the source’s umwelt as well. In other words, the umwelt of the source has been shaped or modified before the message is transmitted to the receiver. Moreover, when transmitting the message by means of “effector cue”, the source’s umwelt would be affected again. For the receiver, the message is a receptor cue and the perception of the message, as a process, would affect the umwelt of the receiver and thus the semiosphere. If the receiver in our model responds to the message by means of “feedback”, the receiver becomes the source in turn and such feedback can be regarded as an effector cue, which would also affect the umwelt again. Therefore, for both source and receiver in intercultural communication, the interaction of between their umwelt and semiosis can be continuous; even though the message, or the cues, seems to be the only link between source and the receiver, the affection on the umwelt-semiosis is the fundamental factor that can decide effectiveness of the communication.

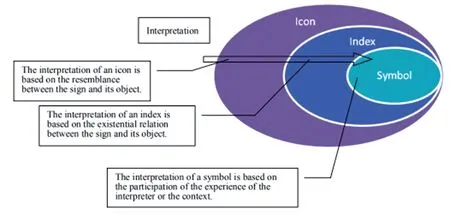

Therefore, to further investigate how the communication process may affect the umwelt of the communicators, we should examine how a subject perceives and operates with the message. As a message could be referred to as representamen or sign in Peircean semiotics, Peirce’s perspectives on how signs are perceived are significantly illuminative. In our previous study on visual semiotics (see Shen & Su, 2015), we summarized Peirce’s typology of icon, index, and symbol to elaborate on the relationship between representamen and object. We used a model as in Figure 4 to illustrate the relationship that a symbol is a particular type of index and an index is a particular type of icon.

Figure 4. Icon, index, and symbol (Shen & Su, 2015)

For Peirce, icon is a sort of representamen that signifies the object due to the fact that they share particular character or quality with the objects they represent; an icon is neither true nor false for it “affords no ground for an interpretation of it as referring to actual existence” (CP 2.251) and iconicity for Peirce is “…a feeling, I mean an instance of that kind of consciousness which involves no analysis, comparison or any process whatsoever, nor consists in whole or in part of any act by which one stretch of consciousness is distinguished from another, which has its own positive quality which consists in nothing else, and which is of itself all that it is, however it may have been brought about” (CP 1.306). Hence, when perceiving a message or a cue, a subject starts by perceiving it as an icon and such perception, or interpretation, is in the first place what Peirce termed “immediate interpretant”, which is “the interpretant as it is revealed in the right understanding of the Sign itself, and is ordinarily called the meaning of the sign” (CP 4.536). For Peirce, the immediate interpretant is the interpretant within the representamen and all representamen must have such immediate interpretability. Consequently, all perceptions involve in the first place an immediate interpretation, or immediate perception and we may term the affection of immediate interpretant on the umwelt as immediate affection. Such perception and affection exist in all types of communicative scenarios, be they intracultural or intercultural.

An index, nevertheless, depends upon the relation between the representamen and the object. According to Peirce, an index refers to the object that “it denotes by virtue of being really affected by that object” (Peirce, [1940]2011, p. 102); it is a sign whose ground is based on contiguity in time and space and it stands for something by direct connection with the object (CP 2.297) while indexicality “would be more accurately described as the vividness of a consciousness of the feeling” (CP 1.306). Thus, when perceiving a cue as an index, a subject is actually perceiving the indexical relationship between the sign and the object. When such an indexical relationship is accustomed, such as by law, it can then be perceived as a symbol. In Peirce’s words, for a representamen to be regarded as a symbol, it should refer to the object that “it denotes by virtue of a law, usually an association of general ideas, which operates to cause the symbol to be interpreted as referring to that object”(Peirce, [1940]2011, p. 103). In other words, the symbolic relationship can be considered the generalized form of indexical relationship. For Peirce, the indexical relationship is perceived or interpreted through the Dynamic Interpretant which is “the actual effect which the Sign, as a Sign, really determines” while the symbolic relationship is perceived or interpreted as the Final Interpretant which “refers to the manner in which the Sign tends to represent itself to be related to its Object” (CP 4.536). Hence, Final Interpretant can also be considered the guarantee or the generalized supposition that everybody would perceive the same symbolic relationship.

Therefore, in our discussion on the process of intercultural communication (Shen, 2010), we regarded it a hypothetical scenario that the message (representamen) would be interpreted to stand for the same object and thus the same interpretant as “successful communication”. However, a key point, or rather a paradox that should be highlighted here is that as the dynamic interpretant is a single actual event, the indexical relationship is not a priori to the interpretation or perception, but a result of the perceiving or interpreting. This assertion aligns with Kull’s (2018, p. 455) explanation on “semiosis-as-choice”, which complements the description of Peirce’s trichotomy:

The aspects in the choice process that correspond to the three relata can be described as follows. Representamen by itself is ambiguous, as it is possible to interpret it in various ways. This means that representamen may refer to different objects. In semiosis, a choice is made between these possibilities, which appear as options, and representamen becomes related to a particular object. This relation is a decision, which is the same as interpretant. Representamen, object and interpretant emerge together at the event of choice-making…semiosis supposes a choice between options. (p. 455)

In other words, interpretation or semiosis is a result of the choice of individuals; it is individual’s choice that would determine the perceived indexical relationship, which renders the perception varied. Hence, the Final Interpretant, which according to Peirce is a generalized form of Dynamic Interpretant, cannot be guaranteed either. This may also explain why Peirce stated that “I confess that my own conception of this third interpretant is not yet quite free from mist” (CP 4.536).

Moreover, according to the umwelt-semiosis framework we discussed above, semiosis is mutually affective and the subject’s umwelt cannot be interpreted by another subject directly (as in the bubble metaphor) but can be affected indirectly by others (as in the music metaphor). Therefore, in a scenario of communication, the communicators’ umwelts are constantly affected by themselves and by others, which in return renders their semiosis constantly being affected as well.

To summarize, for intercultural communication, the distinguished conceptualizations of index and symbol suffice to explain the various scenarios. First, even though all subjects are able to perceive a sign as an icon, their further perception of the sign as an index may differ because it is a single choice and because they perceive by means of their respective umwelts that are different and cannot be accessed by each other directly. A consequence of this is that the symbolic relationship that is perceived on the basis of repeated and generalized indexical relationships can be perceived in different ways as well.

However, this by no means indicates that the differences in perceptions cannot be overcome. Instead, considering the interactive umwelt-semiosis framework, the communication process, be it creating the message or receiving the message, is also a process of shaping or reshaping the communicators’ umwelt. In other words, intercultural communication is a self-affecting process; for communicators involved in the intercultural communication process, their manners of thinking and behaving can always affect the communication and the communication action can also affect the manners of thinking and behaving as well. Therefore, when involved in intercultural communication, it is possible for either the source or the receiver as a subject to consciously manipulate the affection on their umwelt-semiosis to enhance the mutual understanding or, the “success” of intercultural communication. In our concluding remarks, we will argue that to realize such manipulation, we should adopt a triadic viewpoint to take the place of the dualism that has dominated sociological studies such as intercultural communication.

5. Conclusion

This paper has elaborated in detail the dynamicity of the intercultural communication process. Based on the review of dynamic features of both culture and communication, we adopted an umwelt-semiosis framework derived from semiotics to analyze in detail the dynamicity of intercultural communication. Therefore, whether or not communication between different cultures would be successful is not pre-determined by the differences between the cultural backgrounds of the communicators, but rather can be affected by the process of communicating itself. Hence, such dynamicity renders it possible for the subjects to manipulate the affection on and of the umweltsemiosis so as to promote the success of intercultural communication.

Nevertheless, the dynamicity of intercultural communication is one of the least investigated topics in the existing studies. A key reason is that they are to a large extent oriented to paradigms of function or discovery and rely dominantly on positivism and empirical philosophy (Muhammad Umar, Rosli, & Syarizan, 2018), which can be largely traced to Cartesian thought, especially the mind/body dualism (Bertucio, 2017). Cartesian dualism has been the source of a range of dichotomies such as idea/material, mind-dependent/mind-independent, mind/world, subject/object, culture/nature, content/expression, and event/description (Campbell, 2018, p. 540) while such dichotomies tend to ignore the “middle” in between, that is, the process linking both the body and the mind. In our research on intercultural communication competence, we conceptualized individual’s adaptations as the “middle” referring to the semiosis-as-choice by abduction (Shen, Shen, & Zhou, in press). Yet the recognition of the “middle” should be more broadly applied if we are to understand the complicated issues and phenomena of intercultural communication. We can problematize almost any culturally specific manner of thinking and behaving with questions of how and why rather than simply describing what or prescribing so what. It may be more valuable to find out individual’s process of forming or transforming of the tea-coffee cultural differences. Such investigation will surely involve much anthropological analysis but the recognition of the “middle” must be the prerequisite.

Language and Semiotic Studies2020年2期

Language and Semiotic Studies2020年2期

- Language and Semiotic Studies的其它文章

- Towards Semiotics of Art in Record of Music

- Aspects of Transitivity in Select Social Transformation Discourse in Nigeria

- Deducing the Intonation of Chinese Characters in Suzhou-Zhongzhou Dialect by Its Singing Technique in Kunqu: A New Probe into Ancient Chinese Phonology

- Teaching Indigenous Knowledge System to Revitalize and Maintain Vulnerable Aspects of Indigenous Nigerian Languages’ Vocabulary: The Igbo Language Example

- A Statistical Approach to Annotation in the English Translation of Chinese Classics: A Case Study of the Four English Versions of Fushengliuji1

- L3 French Conceptual Transfer in the Acquisition of L2 English Motion Events among Native Chinese Speakers