Teaching Indigenous Knowledge System to Revitalize and Maintain Vulnerable Aspects of Indigenous Nigerian Languages’ Vocabulary: The Igbo Language Example

Friday Ude & Ogbonna Anyanwu

University of Uyo, Nigeria

Abstract

Keywords: indigenous, atrophy, attrition, endangerment, extinction

1. Introduction

The ability to communicate clearly is very important to people of all cultures, and language is central to communication and for the sustenance of a people’s culture. Language is at the heart of culture and knowledge retention. It is the vehicle through which the constituents of a people’s culture are acquired, communicated, shared and transmitted from one generation to another. The ability to communicate effectively in one’s indigenous language connects one to one’s ethnic group and thus helps to get one acquainted with the indigenous knowledge system which will help in shaping one’s identity. Nigeria is a multilingual nation and language provisions of the Federal Government of Nigeria in its National Policy on Education (NPE) (1977) (revised 1981, 1998, 2004, 2007 and 2013) acknowledges the importance of the Nigerian indigenous languages in the education of the child although practical and significant steps have not been taken to ensure the realization of the language policy statement. It states that the primary school child should be taught in the first three years of primary education in the child’s indigenous language or the language of the immediate environment. Afterwards, the child’s indigenous language or the language of the immediate environment will continuously be taught as a school subject throughout primary and secondary education. In line with the language provisions of the NPE, the Igbo language is supposed to be the language of instruction of early primary education and a school subject from senior primary and all through secondary education in southeastern Nigeria where the Igbo language is largely and homogenously spoken.

However, a cursory look at the Igbo language curriculum for pupils and students at the primary and secondary levels shows no provision for the teaching of any aspects of Igbo indigenous knowledge systems, and this has resulted in the attrition and atrophy of vocabulary items associated with such knowledge systems, especially in the speech of primary and secondary students in urban and semi-urban areas of Igbo speech communities where the practices of the knowledge systems are quite remote. The present paper, therefore, examines the benefits derivable from integrating the Igbo indigenous knowledge systems into the Igbo language curriculum of secondary school students of Igbo origin in southeastern Nigeria where the Igbo language is largely and homogenously spoken.

The present study contributes to the endangerment studies on the Igbo language and follows findings from studies such as Osuagwu and Anyanwu (2015), Anyanwu (2016), Anyanwu and Atoyebi (2018) and some others (which have shown that certain aspects of Igbo indigenous knowledge system vocabulary items are endangered, especially in the speech of the youth population) to highlight some Igbo indigenous knowledge system vocabulary items that are potentially suffering attrition. The paper concludes by suggesting how the teaching of the Igbo indigenous knowledge systems can help to revitalize and maintain those vulnerable aspects of indigenous knowledge vocabulary.

The study adopts a qualitative descriptive research design. The Igbo vocabulary data presented in the study were collected through elicitation interviews from selected respondents and analyzed descriptively. The study area consisted of six Local Government Areas from the States of Abia and Imo States, southeastern Nigeria.

2. Indigenous Knowledge Systems

Indigenous knowledge systems constitute the local knowledge that is unique to a given culture or society. They are the basis for local-level decision making in agriculture, health care, food preparation, education, natural-resource management, and a host of other activities in rural communities (Warren, 1991a, b). They are dynamic, and are continually influenced by internal creativity and experimentation as well as contact with external systems (Flavier et al., 1995). They are manifested in human experience, organized and ordered into accumulated knowledge with the objective of achieving quality of life and to create a livable environment for both human and other forms of life. They include a set of perceptions, information and behaviors that guide a local community’s members.

Indigenous knowledge systems and practices are embedded within indigenous languages and also institutionalized by them. They include the traditional songs, stories, legends, dreams, methods and practices (sometimes preserved in artifacts). Indigenous languages are thus repositories of indigenous knowledge and are also the bedrock upon which indigenous knowledge systems are built, developed and sustained. There is an interface of mutual sustainability between indigenous languages and indigenous knowledge systems. Indigenous knowledge systems are embedded in and disseminated through indigenous languages and indigenous languages are preserved in indigenous knowledge systems.

Indigenous knowledge systems encompass tacit and explicit/practical knowledge that is held and made use of by people who regard themselves as indigenous to a particular place. It is invested with a sacred quality and systematic unity, supplying the foundation on which the members of a traditional community sense their community’s personal identity and ancestral anchorage. It is part of the culture and history of the local community. In certain parts of Africa, people’s lives are greatly affected by indigenous knowledge, since they rely on it for medicinal and herbal needs, food supply, conflict resolution and spiritual growth. Indigenous knowledge is indeed the cornerstone for the building of identity and ensuring coherence of social structures within communities.

Indigenous knowledge systems serve as the base for individuals to process information, promote efficient allocation of resources and help in production methods and decisions. Indigenous knowledge systems are derived from experiences and observations both from a community’s current and past generations with a knowledge base understood by participants through production methods, verbal sayings, myths, cultural events which are unique to the community and its environment. The knowledge base provides cultural acceptance and identity and participants relate to all events and experiences from this worldview. According to Emery (1997), the totality of what constitutes the indigenous knowledge system can be captured thus:

(i) It is practical common sense, based on teachings and experience passed on from generation to generation;

(ii) it covers knowledge of the environment and the relationship between things;

(iii) it is holistic and cannot be compartmentalized or separated from the people who hold it because it is rooted in the spiritual health, culture and language of the people;

(iv) it is an authority system that sets out the rules governing the use of resources;

(v) it is a way of life (wisdom) in using knowledge in good ways;

(vi) it gives credibility to people.

Indigenous knowledge systems are, however, vulnerable to change since they are mostly stored in people’s minds and passed on through generations by word of mouth rather than in written form.

Certain factors such as development processes, rural/urban migration and changes to population structure as a result of famine, epidemics, displacement or war all constitute a threat to indigenous knowledge. As also noted by Mapara (2009), indigenous knowledge systems are under threat from modern technology because even in remote areas the powers that push global or just non-local content such as radio and television broadcasting and advertising, among others, are much stronger than those pulling local content. Language endangerment or the endangerment of any aspects of a language (or extinction in some cases) is a great threat to indigenous knowledge systems. The extinction or endangerment of a language or any of its aspects means the disappearance of the indigenous knowledge it carries. This is the situation which some indigenous Nigerian languages and knowledge systems are grappling with.

3. The Endangerment of Indigenous Nigerian Languages: A Threat to Nigerian Indigenous Knowledge Systems

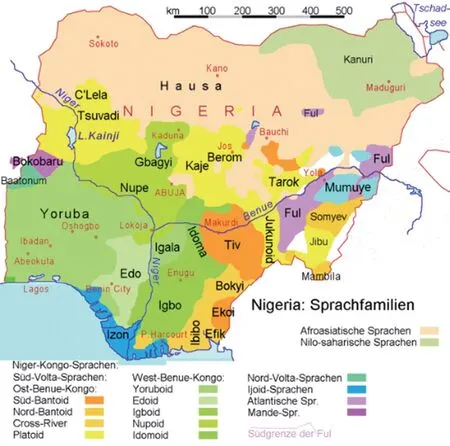

Nigeria is linguistically diverse, with hundreds of different indigenous languages. These languages are also repositories of diverse indigenous Nigerian knowledge systems. The linguistic situation in Nigeria is quite diverse (cf. Figure 1). The official language is English but with three national indigenous (regional) languages (Hausa, Igbo and Yoruba) which are also referred to as “major” by virtue of the population of their speakers. Hausa is spoken by about 20 million people in the north; Yoruba, spoken by about 19 million in the southwest; and Igbo, spoken by about 17 million people in part of the southeast (Udoh, 2014). In addition to these three major indigenous languages, there are more than 400 “minor” indigenous languages (Crozier & Blench, 1992), which Egbokhare, Oyetade, Urua and Amfani (2001) have reduced to 113 language clusters. With the reclassification, some of the non-major indigenous languages have some degree of official status in their locality and are even used as lingua franca (e.g. Efik, Ibibio, Edo, etc.). Still sandwiched within the network of major and non-major indigenous languages is the Nigerian Pidgin (English) which also enjoys the status of an unofficial national lingua franca.

Whereas the minority languages in the Nigerian context are languages that are spoken by the minority ethnic groups, the major Nigerian languages (Hausa, Yoruba and Igbo) are spoken by the three major ethnic groups. However, the different indigenous Nigerian languages are faced with threats of various degrees of endangerment. Crozier and Blench (1992) list some eight Nigerian languages, including Bassa-Kontagora with only 10 surviving speakers as of 1987. Also Crozier and Blench (1992), and more recently Blench (2012) record 489 languages for Nigeria, with about 200 of these being severely endangered and 20 moribund languages. Ugwuoke (1992), relying on Brenzinger et al.’s (1991) criterion of an endangered language, lists about 152 endangered Nigerian languages. Shaeffer (1997) notes that Emai, a language of a small community in Edo State, Nigeria (including about 30 different languages spoken in the area) would probably be dead by the year 2050 since none of them could serve as a lingua franca and were being displaced rapidly by English.

Figure 1. Map showing language groups of Nigeria, adapted from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/languages of Nigeria

Haruna (2007) also lists about 20 languages in northern Nigeria which were extinct or almost extinct, specifically mentioning Bubbure, a West Chadic language of Bauchi state spoken by just one person as of then, and Holma, spoken in Adamawa state by 4 aged speakers in 1987. Thus, the number of indigenous Nigerian languages is dwindling by the day, overwhelmed by the influence of foreign languages, especially English, which enjoys a privileged status in education, administration and the mass media (UNESCO, 2012).Whereas the domains of English usage are ever increasing and becoming all-inclusive, the indigenous Nigerian languages are rapidly shrinking in domains of usage. Although language endangerment is often associated with languages which have few speakers, it is a phenomenon that can affect any language and any aspect of language usage no matter how numerous its speakers are. Given the shrinking domains of use of the indigenous Nigerian languages and when viewed in the light of UNESCO’s (2003) Language Vitality Index listed below (i-viii), Emenanjo (2005) has remarked that no Nigerian language can be said to be safe; not even the three major languages, Hausa, Igbo and Yoruba, especially when it is also possible for certain aspects of a major language vocabulary to suffer attrition/atrophy when the aspects of the culture (indigenous knowledge) expressed by such vocabulary items are also suffering attrition (Anyanwu, 2016; Anyanwu & Atoyebi, 2018).

(i) Intergenerational transmission;

(ii) Absolute number of fluent and committed speakers;

(iii) Proportion of speakers within the total population;

(iv) Shifts in domains of actual language use;

(v) Availability of materials for language use and literary;

(vi) Governmental and institutional language attitudes and policies including official status and use;

(vii) Community members’ attitudes towards their own language;

(viii) Nature, type and amount of quality of language documentation.

Thus, Nigerians can be described as not having stopped speaking languages, but they are not speaking more in their mother tongues and this is largely due to several factors which have been identified to include: the status of English as a lingua Franca in Nigeria, negative attitude towards the indigenous languages, lack of lucrative career opportunities for graduates of indigenous Nigerian languages, lack of holistic language curriculum in the indigenous languages, inadequate scientific terminology in the indigenous languages, very limited research and publications in the indigenous languages, lack of policy to protect indigenous languages and many language-policy statements which are non-reactive/ad hoc declarations lacking a planning component.

While the attitude of many Nigerian adults towards their language and culture is reprehensible, what is also happening to the younger generation as far as the mother tongue usage is concerned is both alarming and discouraging. The Nigerian youths are caught in a web of a linguistic choice between English and the indigenous languages and most of them obviously succumb to a choice of English, which they feel will put them in a proper perspective in the context of globalization. For many children born and raised in the cities by elite Nigerian parents, they are not interested in their mother tongues and it has become increasingly the norm for such children to have their first language be English. This fact is made worse by the fact that the parents of such children send them to private primary and secondary schools where the pupils and students are not taught in any Nigerian languages but in English. It is even a punishable offence in some public and private primary and secondary schools to communicate within the school premises in any Nigerian languages, which are termed as vernaculars. The scenarios presented above are all contributors to the threat to different indigenous Nigerian languages to various degrees of endangerment and possible extinction.

The extinction, endangerment or attrition of a language or any of its aspects is also a disappearance of valuable sources and important links for linguistic, historical, anthropological and social reconstruction and interpretation (Udoh & Anyanwu, 2015). It is, in fact, a loss of the indigenous knowledge systems embedded in such languages. The inseparable nature of indigenous language from culture makes it of much significance to the sustenance of indigenous knowledge systems. The loss of language means the loss of human diversity and all the knowledge systems contained therein. Given the scenario that most indigenous Nigerian languages are not safe but are facing different forms of threats ranging from potential endangerment, actual endangerment, serious endangerment, moribund status or even extinction, the alarm of these threats to even the major indigenous languages, especially the Igbo language, has drawn a wide range of reactions. This is even more noticeable when, towards the end of 2006, a report from UNESCO in one of the Nigerian dailies predicted that the Igbo language, among other minor African languages, will be extinct by the year 2050. Even before the prediction from UNESCO there had been studies making reference to the endangerment of Igbo, and many more studies have also reacted to the UNESCO’s prediction; some of these later studies have further tried to affirm the prediction, pointing at certain pieces of evidence while others have deeply faulted the prediction.

4. Igbo Language and the Phenomenon of Endangerment

Igbo refers to both the language whose indigenous speakers live mainly in the southeastern states of Abia, Anambra, Ebonyi, Enugu, Imo and parts of Delta and Rivers States.

Figure 2. South East States of Nigeria where Igbo is largely and indigenously spoken

Within the Igbo speech communities, there are scores of regional dialects. Since all Igbo dialects derive from one proto-Igbo language, they share many phonological, grammatical and lexical features. Yet, as would be expected, they also differ in certain phonological, lexical and grammatical ways. These differences, however, do not inhibit effective communication or mutual intelligibility (Anyanwu, 2010).

The vibrant use of Igbo just as has been noted for most Nigerian languages is being threatened within the speech of its adult native speakers and also among youth population in the south eastern states where Igbo was once one of the compulsory subjects for students especially at the senior secondary level. The factors leading to this threat may include the following: (i) The English language plays a dominant role in media, education and politics. (ii) Parents believe that the English language will bring better prospects for them and their children which is the reason why the parents do not get motivated to transmit the language to their children. (iii) The students themselves believe that their world views will be highly limited in scope with Igbo unlike English that will provide a great access to ICT and technological breakthroughs of globalization.

As has been noted by Osuagwu and Anyanwu (2015) and Anyanwu (2016), most speakers of Igbo, regardless of their level of education, get involved in code-mixing especially in predominantly Igbo based constructions. That is, there is hardly any sentence rendered in Igbo by most Igbo speakers which is not laced with chunks of English words. The code-mixing phenomenon is a reflection of the attitude of unconscious ‘apathy’ of Igbo speakers towards their Igbo even when the English words used in the codemixed expressions have equivalents in Igbo. Again, this practice, which is most often an unconscious activity, has the negative implication of continuously shrinking the functional domains of Igbo language vocabulary usage while expanding that of English, and some studies, discussed in the next section, have shown that some aspects of the indigenous Igbo language vocabulary are suffering attrition.

There are millions speaking Igbo. By this fact, Igbo is not endangered; but there are areas of the vocabulary of the language which are suffering atrophy, which is an indication of endangerment. Some recent studies have been conducted to check the vitality of certain aspects of Igbo vocabulary usage in order to glimpse the degree to which some of the vocabulary items are diminishing in the speech of the speakers. Such studies include Osuagwu and Anyanwu (2015), Anyanwu (2016) and Anyanwu and Atoyebi (2018).

Osuagwu and Anyanwu (2015) conducted a vocabulary test of twenty-four groups of words among 384 adult speakers (192 males and 192 females) in Aba metropolis, the commercial nerve centre of Abia State, Nigeria. The group of words tested included words for body parts, foods and vegetables, birds’ names, greetings, family/kinship, telling time, insects/pests, animals, reptiles, artifacts, colors, fruits, instruments, furniture, kitchen utensils, place names, persons/occupations, sicknesses, deities, jewelries, water bodies, mountains, naira denominations, vocatives and building/carpentry materials. The result of their vocabulary test shows that the total average usage of the entire twenty-four groups of words sampled was 49.9%. This simply means that it is roughly only half of the population sampled that uses the indigenous Igbo words. Based on the vocabulary test results, they concluded that: (i) the intergenerational transfer of Igbo is getting weak; (ii) the active speakers within the total population of Igbo speakers is reducing; (iii) the existing domains for Igbo usage are shrinking; (iv) Igbo is not increasingly breaking new grounds or creating new domains of usage; (v) there is poor attitude of indigenous Igbo speakers towards their language and (vi) that the Igbo speakers have exceptionally strong receptivity to change. These observations are similar to the symptoms of reduced speaker competence, rapidly decreasing child competence, repressive language policies in schools, intense code-switching and code-mixing, assimilation into new languages such as pidgins and creoles and the depletion of the population of monolingual elderly speakers, which an earlier study, Azuonye (2002) had noted, and are indications that Igbo language is being endangered.

Anyanwu (2016) goes further to examine the phenomenon of vocabulary endangerment of the twenty-four groups of words tested by Anyanwu and Osuagwu (2015) in Igbo and Ibibio in order to assess how faithful speakers of both languages are in using the indigenous vocabularies of their languages in their daily interactions. Respondents who were grouped into clusters were chosen from Aba and Uyo metropolises where Igbo and Ibibio, respectively, are indigenously spoken. The findings of the paper among others reveal that there is evidence of vocabulary endangerment in the speech of both the Igbo and Ibibio respondents. However, compared with Igbo respondents with a total average of 48.6% usage of the vocabulary items studied, Ibibio respondents had a total average usage of 68.1%. This shows that the Igbo respondents in the study, unlike their Ibibio counterparts, manifested a much higher apathy in the use of their vocabulary items, a fact which obviously shows that vocabulary items are more endangered in the speech of Igbo respondents.

Anyanwu and Atoyebi’s (2018) study explores the gradual disappearance of the Igbo indigenous occupational terminologies and concludes that two main factors are responsible for the disappearance of indigenous words. The first is connected to the negative attitudes of Igbo speakers towards their language. An Igbo speaker would rather refer to indigenous occupations/professions by their English terminologies rather than with Igbo words. Second is the disappearance of the indigenous occupations themselves due to a shift in economic trends. Because these occupations are no longer an everyday feature of the speech community, speakers of Igbo are beginning to forget what they are called. The study made the following specific observations: respondents’ proficiency level in the indigenous expressions in Igbo directly correlates to their age. The oldest generation of respondents (55-64 years) has the highest performance score in the study. The performance score of the respondents continue to decline as the age group decreases. The reason for the difference in performance scores can also be associated with the extent of exposure to the English language. The older generations of speakers have limited exposure to English compared to the younger ones.

Some agentive words of occupation/profession are more susceptible to disappearing than others; some of the occupations are obsolete and there is also the ongoing shift in the economic structure of the communities. The study notes that a profession like “town-crier” ranks lowest on the percentage grid because it is almost obsolete. Also, professions like “palm fruit cutter”, “palm wine tapper”, and “wrestler”, are also victims of the economic shift. The study observes that these ways of economic life have been abandoned for the more lucrative commerceoriented life, namely, buying and selling, noting that the less presence a profession has in a community, the higher the possibility of speakers not using the indigenous terminology that is associated with the profession.

5. Revitalizing the Igbo Indigenous Knowledge Vocabulary by Teaching the Indigenous Igbo Knowledge System

At the 31st Session of the UNESCO General Conference (2001), the unanimously adopted Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity recognized a relationship between biodiversity, cultural diversity, and linguistic diversity. UNESCO’s action plan recommends that Member States, in conjunction with speaker communities, undertake steps to:

(i) sustain the linguistic diversity of humanity by supporting the expression, creation, and dissemination of the greatest possible number of languages;

(ii) encourage linguistic diversity at all levels of education, wherever possible, and foster the learning of several languages from the youngest age;

(iii) incorporate, where appropriate, traditional pedagogies into the education process with a view to preserving and making full use of culturally-appropriate methods of communication and transmission of knowledge; and where permitted by speaker communities, encourage universal access to information in the public domain through the global network, as well as promoting linguistic diversity in cyberspace.

Again, this is similarly stated in Article 13-1 in the United Nations (2007) adopted Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (which includes language rights) which states: “Indigenous peoples have the right to revitalize, use, develop and transmit to future generations their histories, languages, oral traditions, philosophies, writing systems and literatures, and to designate and retain their own names for communities, places and persons.”

The above steps are also in tandem with UNESCO’s (1953) declaration which categorically states that humans amass their potentials greatly through the use of mother tongue, while any attempt to continually expose them to a foreign language leads to inadequacy and naturally retards human cognitive maturation and development and intellectual capacities. Today, there is a growing recognition of the value of indigenous knowledge systems, especially for sustainable language maintenance and development. Therefore, it is very important that in order to sustain indigenous knowledge systems in traditional communities they should be integrated into the school curriculum, where culturally and educationally appropriate, to enhance and strengthen Igbo language vocabulary retention and stem the tide of Igbo vocabulary endangerment. The teaching and learning of the Igbo indigenous system will be a step in the right direction in order to ensure the realization of UNESCO’s mandate for Igbo and its community of speakers. The teaching can be done in different ways such as: comprehension passages, practical discussions, excursions, audio-visual materials, dramatization, etc. A large number of Igbo indigenous knowledge systems can be taught, and in the following sections we have highlighted some of them and the specific vocabulary items that can be learned from them.

5.1 Iche / iwa oji ‘breaking kola nut ceremony’

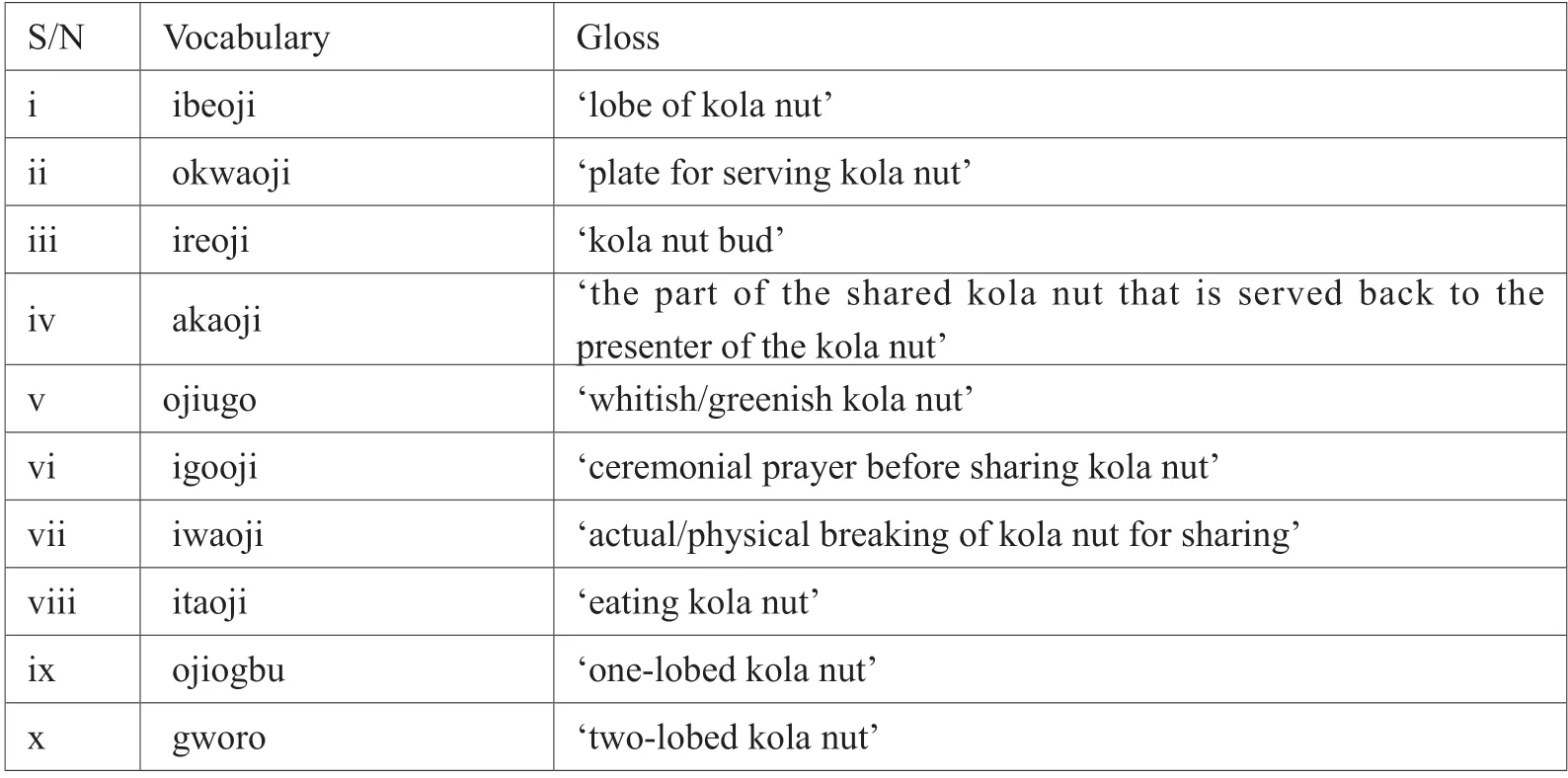

There is a popular saying in Nigeria: Kola nut is grown in the West (Yoruba area), eaten in the North (Hausa area) and celebrated and revered in the East (Igbo area). The ịwa/ịta oji ceremony is generally a very significant feature of any serious gathering in Igbo land which portrays a sense of peace, acceptance, happiness between men and even between man and the gods. It features in welcoming guests, worshipping the gods, traditional marriages, naming ceremonies, coronations, etc. Teaching this knowledge system will ensure that the following associated vocabulary items (Table 1) are learnt, retained and used appropriately.

Figure 3. Breaking of kola nut ceremony (excerpted from http://sconnectnigeria.comarticlessymbolic-uses-of-the-kola-nut-in-a-traditional-igbo-society)

Table 1. Associated vocabulary items of kola nut breaking in Igbo

5.2 Igbamgba ‘traditional wrestling’

Wrestling has always been an integral part of the Igbo traditional society, both an entertainment and as a way for the young adult men to prove their mettle among their peers. It is usually a village square event. It is during the wrestling events that male Igbo youths showcase themselves through their wrestling exploits as being strong, virile, physically mature and potentially ready to marry young maidens who are equally ready for marriage and usually form part of the audience that admirably cheer the wrestlers. This aspect of the Igbo culture is suffering attrition and so are the vocabulary items associated with them. The male youths no longer see this activity as being in line with modernity in the midst of so much new social media surrounding them. Some of the associated vocabulary items to be learnt by teaching wrestling as an indigenous knowledge system include those in Table 2.

Figure 4. A traditional Igbo wrestling match (excerpted from https://www.facts.ngcultureigbotraditional-wrestling)

Table 2. Associated vocabulary of traditional wrestling in Igbo

5.3 Egwu onwa ‘moonlight play’

The moonlight play is usually done under the full moon and used to teach histories and legends to both adults and children. Within the Igbo traditional society families live closer to each other and one way of recreating in the evening, especially under the full moon, is to engage in moonlight plays. Both children and adults engage themselves in different forms of entertainment. This aspect of the Igbo culture is endangered. Migration to the urban centers as well as the feeling of insecurity have affected this kind of communal living to the point that, at present, it is very unlikely to find any communities engaging in the moonlight plays. The vocabulary items associated with this culture are going extinct as well, and can be revived by teaching them. Some of the associated vocabulary items include those in Table 3.

Figure 5. Children’s moonlight play (excerpted from https://www.informationng.com/2016/03/9-childhood-games-anyone-who-grew-up-in-nigeria-can-never-forget.html)

Table 3. Associated vocabulary of traditional moonlight play in Igbo

5.4 Ichunta ‘hunting’

Like in most traditional societies, hunting is part of the occupational and cultural life of the Igbo people. This is the activity of hunting for game (animals and birds) in the bush, mainly for food. It is an activity mainly engaged in by men and, depending on the nature of the target prey, it can be done during the day time or night. This aspect of the Igbo occupational and cultural life is no longer robust and therefore not intergenerationally transferred. Thus, the linguistic terms associated with hunting are also not transferred to the new generations and are, therefore, threatened with extinction. Some of the associated vocabulary items concerning hunting which can be integrated into the classroom teaching are shown in Table 4.

Figure 6. A Typical Igbo hunter targeting prey (picture taken by the authors)

Table 4. Associated vocabulary of traditional hunting in Igbo

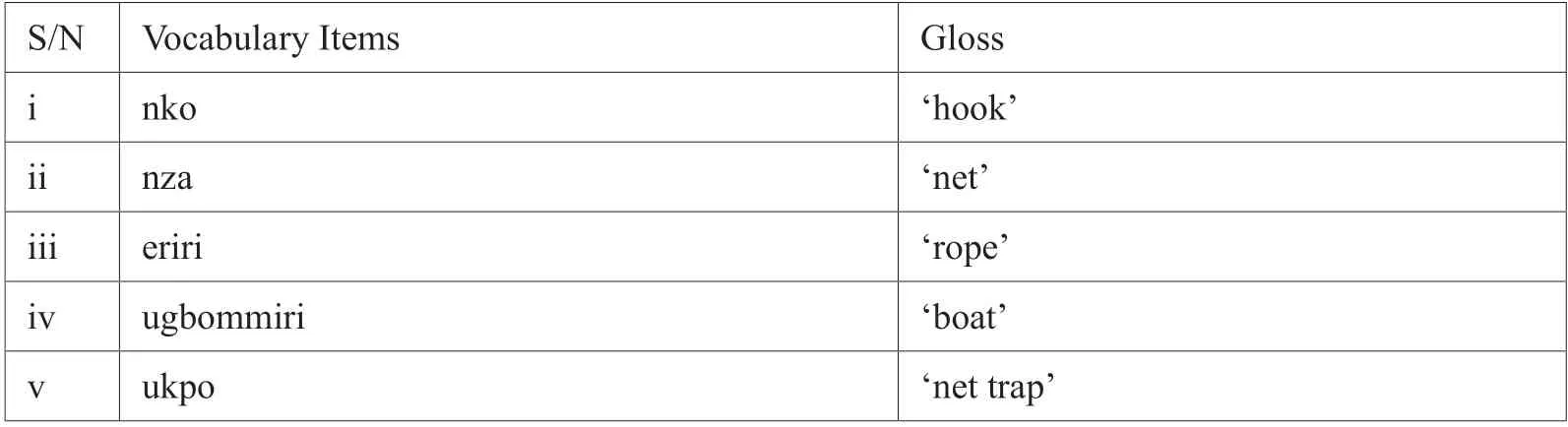

5.5 Ikuazu ‘fishing’

Fishing activities are very prevalent in the Igbo coastal communities and are maledominated. There are vocabulary items associated with fishing activities. The vocabulary items generally reflect the tools which are used in fishing. With the advent of modern ways of fishing, most of the traditional tools are going extinct and are becoming less and less part of the linguistic repertoire of fishing communities even within the Igbo traditional fishing communities. Table 5 contains some of the associated vocabulary items of tradition fishing in the language which can form part of teaching activity of traditional fishing in the Igbo language.

Figure 7. A picture of a fisherman (excerpted from https://www.nairaland.com/3933654/hausafishermen-far-away-home)

Table 5. Associated vocabulary of traditional fishing in Igbo

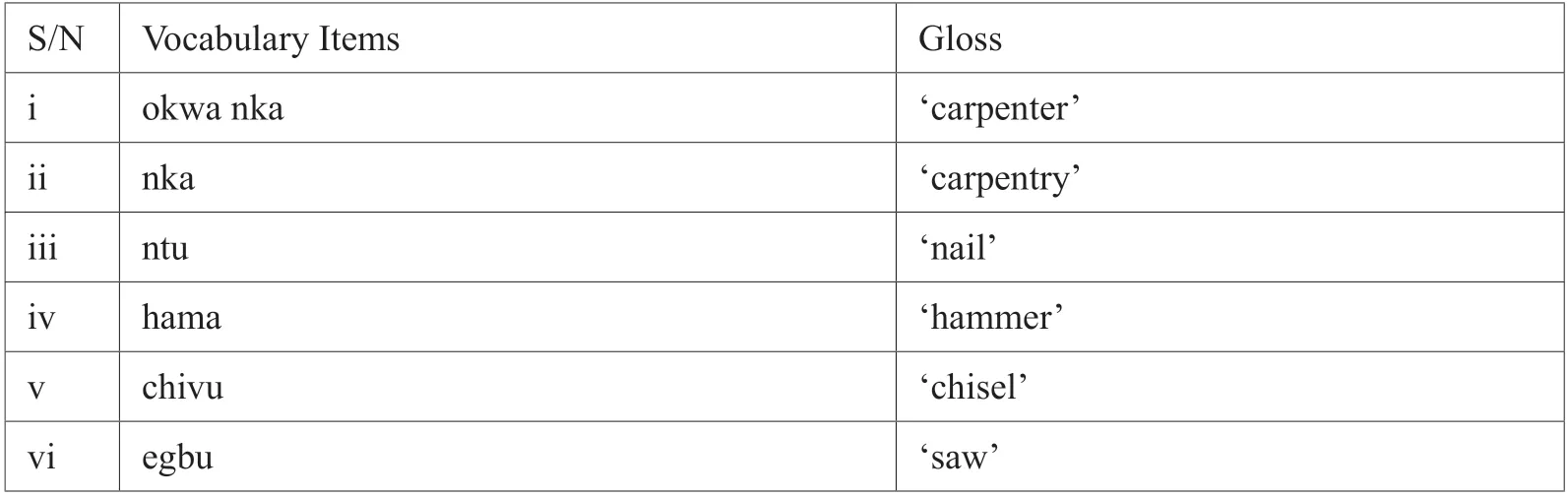

5.6 Ikwa Nka ‘carpentry’

Carpentry is an indigenous male-dominated occupational activity in the Igbo communities. Carpentry used to be one of the productive and robust traditional occupations to the extent that apprentices would flock around any skilful carpentry ‘masters’ to learn the craft. In the contemporary Igbo communities, however, the scenario is changing and one hardly finds the younger generations showing interest in learning the occupation. This being the case, the linguistic knowledge and the carpentry-associated lexical items are not being transmitted across the generations, a situation that portends danger for this aspect of the Igbo indigenous knowledge. Some of the vocabulary items associated with carpentry which can also be taught and learnt in schools are listed in Table 6.

Figure 8. A carpenter in his workshop (picture taken by the authors)

Table 6. Associated vocabulary of traditional carpentry in Igbo

5.7 Iku Ngwo ‘palm wine tapping’

Palm wine tapping is the act of tapping the top trunk of a raffia or palm tree for palm wine. Palm tapping is indigenous to the Igbo people and it used to be a very popular source of income for the palm tappers. In and around most Igbo families’ compounds, one would see the nursing of raffia seedlings because of the economic proceeds from the palm wine tapping business. At the moment, there is an absolute lack of interest in palm wine tapping to the extent that imported drinks are used in many traditional ceremonies where the palm wine should have been used. With people finding alternative means of economic livelihood outside palm tapping, this knowledge system with its linguistic components is suffering atrophy. Some of the vocabulary items associated with palm tapping are listed in Table 7.

Figure 9. A palm tapper climbing to tap palm wine (picture taken by the authors)

Table 7. Associated vocabulary of traditional palm wine tapping in Igbo

5.8 Ikpu Uro ‘pottery’

Pottery, the process of creating objects with clay, is an aspect of the indigenous life of the Igbo people and it is a craft that is mainly engaged in by the women. This craft is on the verge of extinction since there are few new persons engaging in pottery as a profitable or recreational occupation. With the loss of interest in pottery, the linguistic aspects of the Igbo culture embedded in it are threatened and near extinction. Some of the associated vocabulary items associated with pottery in Igbo are listed in Table 8.

Figure 10. A potter molding a clay pot (excerpted from https://encryptedtbn.gstatic.com/images)

Table 8. Associated vocabulary of pottery in Igbo

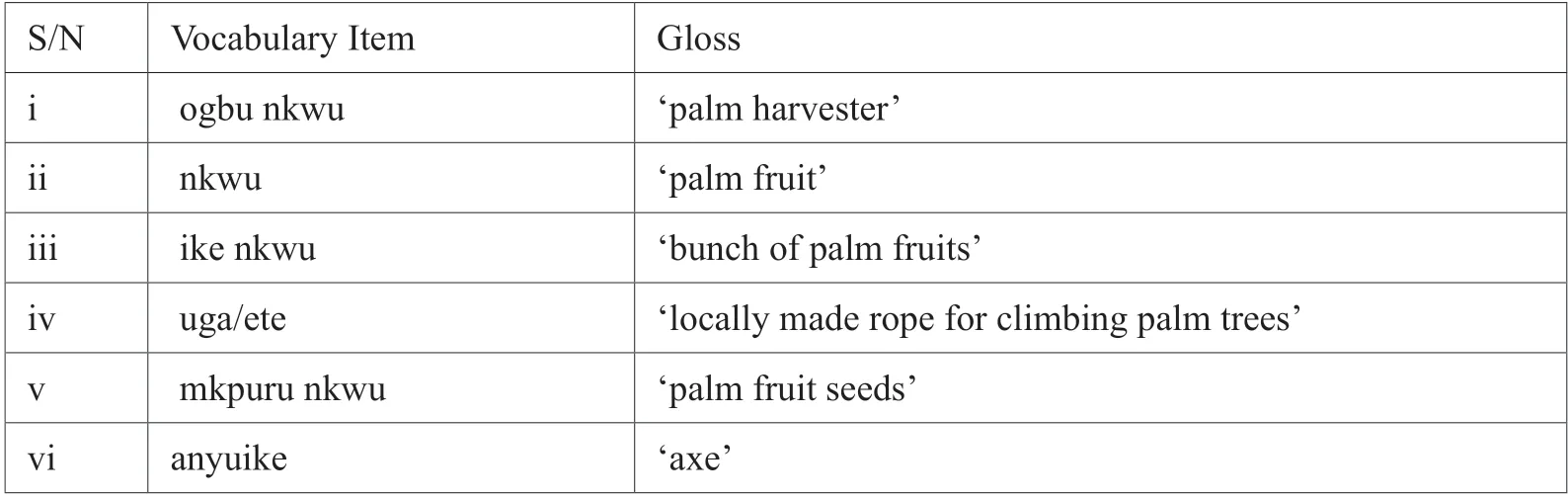

5.10 Igbu Nkwu ‘palm fruit harvesting’

Palm fruit farming is also an indigenous occupation among the Igbo people and still continues to be a great source of economic income till this day. Harvesting the fully grown palm fruits requires the use of certain tools and a skill which the palm fruit harvester must possess. In the traditional Igbo community, several able-bodied individuals were engaged in the occupation of palm fruit harvesting to the extent that they would be scouting for palm fruit farm owners to harvest for. Times have changed, however, and there is presently an acute shortage of palm fruit harvesters, and the very few available ones are overwhelmed by the demands of palm fruit owners who require their services. This occupation is therefore endangered since there are very few men showing interest in it. The vocabulary items associated with the palm fruit harvesting knowledge system are not being inter-generationally transferred and are on the verge of extinction. Some of these vocabulary items are listed in Table 9.

Figure 11. A palm fruit harvester climbing a palm fruit tree (picture taken by the authors)

Table 9. Associated vocabulary of palm fruit harvesting in Igbo

6. Benefits of Integrating the Indigenous Knowledge Systems into the Igbo Language Curriculum

Basically, there are benefits derivable from integrating the indigenous knowledge systems into the Igbo language curriculum geared toward the acquisition and retention of indigenous language vocabulary. Following ideas from Burger (1990), such benefits are discussed below.

Indigenous Igbo communities have lived in harmony with the natural environment and have made use of natural resources without impairing nature’s capacity to regenerate them. Their ways of living were sustainable. It was Igbo Indigenous knowledge systems that shaped their values and attitudes towards the environment, and it is these attitudes and values which have guided their actions and made them sustainable. Therefore, indigenous knowledge can help to develop sensitive and caring values and attitudes, thereby promoting a vision of a sustainable future.

Igbo indigenous knowledge systems are stored in culture in various forms, such as traditions, customs, folk stories, folk songs, folk dramas, legends, proverbs, myths, etc. The utilization of these cultural items as resources in schools can be very effective in bringing indigenous knowledge alive for the students. It would give them the opportunity to conceptualize places and issues not only in the local area but also beyond their immediate experience. Students will already be familiar with some aspects of indigenous culture and, therefore, may find it interesting to learn more about it through these cultural forms. It would also enable active participation as teachers could involve students in collecting folk stories, folk songs, legends, proverbs, etc., that are retold in their community.

In view of its potential value for sustainable development, it is necessary to preserve indigenous knowledge systems for the benefit of future generations. Integrating the indigenous systems into the Igbo language curriculum will be the best way of preserving the indigenous knowledge system. This would motivate students to learn from their parents, grandparents and other adults in the community, and allow them to appreciate and respect their knowledge systems. Such a relationship between young and older generations could help to mitigate the generation gap and help develop intergenerational harmony. Indigenous people, for the first time perhaps, would also get an opportunity to participate in curriculum development. The integration of indigenous knowledge into the school curriculum would thus enable schools to act as agencies for transferring the culture of the society from one generation to the next.

Effective education is always rooted in the philosophy of moving “from the known to the unknown”. Therefore, it is wise to start with the knowledge about the local area which students are familiar with, and then gradually move to the knowledge about regional, national and global environments. Indigenous knowledge can play a significant role in education about the local area and environment since the indigenous people have, over the centuries, developed enormous volumes of knowledge by directly interacting with the environment: knowledge about the soil, climate, water, forest, wildlife, minerals etc. in the locality. This ready-made knowledge system could easily be used in education if appropriate measures are taken to tap the indigenous knowledge, which remains in the memory of local elderly people.

Students can learn much from fieldwork in the local area. This calls for some prior knowledge and understanding. For instance, to be able to understand the relationship between indigenous people, soils and plants, students need to identify the plants and soil types in the local area. One way to get a preliminary knowledge of plants and soil types in the local environment is to consult indigenous people and invite them to teach students in the field. Indigenous people may also be willing to show students collections of artifacts and certain ceremonies and explain their significance and, where appropriate, share with them particular sites of special significance.

7. The Importance of Indigenous Knowledge System in the Sustenance of the Indigenous Language

Indigenous knowledge systems are very important in the preservation and sustenance of indigenous languages, including the Igbo language, and indigenous knowledge systems play vital roles in the sustenance and preservation of the Igbo language as outlined below.

Language is at the heart of the culture and knowledge retention. Without language, the culture of a people and the essence of who they are become completely lost. Language, which is the most fundamental way that cultural information is communicated and preserved, is deeply embedded in the indigenous knowledge systems. Thus, indigenous knowledge systems are very important to the survival of Igbo language and culture. This also requires that any discussion of indigenous knowledge systems must include language retention since the indigenous systems are the repositories of the indigenous languages, which contain irreplaceable cultural knowledge: the cornerstone of indigenous community and family values. Many of the keys to the psychological, social, and physical survival of the people may well be embedded in their language. These keys will be lost as language and culture die. The language is joint creative production that each generation adds to. It contains generations of wisdom going back into antiquity and also contains a significant part of the world’s knowledge and wisdom. If the language is lost, much of the knowledge that it represents is also gone, including the different ways of saying things and the different ways of being, thinking, seeing, and acting.

Also, according to Bernard (1992), linguistic diversity is at least the correlate of diversity of adaptational ideas; ideas about transferring property (or even the idea of creating property itself), curing illness, acquiring food, raising children, distributing power, or settling disputes. He further notes that, by this reasoning, any reduction of language diversity diminishes the adaptational strength of the human species because it lowers the pool of knowledge from which we can draw. Igbo is part of the universal linguistic diversity, and reduction of its potential to contribute to the knowledge of biodiversity will pose a threat to both biodiversity and linguistic diversity.

Igbo family values are embedded and transmitted through the indigenous knowledge systems. Thus it is through vibrant existence of indigenous language systems that parents can transmit to their children the core family values embedded in the knowledge systems. This process ensures that both the Igbo language and its knowledge systems are ultimately saved from extinction.

Studies (e.g. Baker, 1988; Cummins, 1989; Ramirez, 1992) have demonstrated that there is a strong and positive correlation between literacy in the native language and learning a second language such as English. It is not necessary to shun one’s home language to learn a second language and be academically successful in that second language. Cummins (1989) explains that although the surface aspects (e.g., pronunciation, fluency, etc.) of different languages are clearly separate, there is an underlying cognitive/academic proficiency which is common across languages. This “common underlying proficiency” (CUP) makes possible the transfer of cognitive/academic or literacy-related skills across languages. It has also been noted that transfer is much more likely to occur from a minority to majority language because of the greater exposure to literacy in the majority language outside of school and the strong social pressure to learn it. Thus, if indigenous speakers of Igbo ensure that their children acquire Igbo first, the already acquired skills will transfer in their ability to learn English.

Linguistic rights are the human and civil rights concerning the individual and collective right to choose the language or languages for communication in a private or public atmosphere. Other Linguistic rights are always analyzed along the parameters of the degree of territoriality, degree of positive attitude to one’s indigenous language, orientation in terms of assimilation or maintenance of one’s indigenous language and overtness. These entire parameters amount to being faithful to one’s indigenous language, which are here referred to as linguistic fidelity. Being well-versed in the skills of indigenous technology ensures that the vocabulary of the indigenous technology is maintained.

According to Frederico Mayor, the former Director General of UNESCO, the indigenous people of the world possess immense knowledge systems, based on centuries of living close to nature. Living in a rich variety of complex ecosystems, they have an understanding of the properties of plants and animals, the functioning of ecosystems and the techniques for using and managing them that is particular and often detailed. In some of the rural communities, locally occurring species are relied on for basic needs such as foods, medicines, fuel, building materials and other products. Equally, people’s knowledge and perceptions of the environment, and their relationships with it, are often important elements of cultural identity. All these will be preserved as reflected in the language if the Igbo indigenous systems are preserved.

8. Conclusion

Language is the principal means through which the culture of a people is accumulated, shared and transmitted from one generation to another. Language expresses the uniqueness of a group's world view (Kirkness, 1998). In order to quell the disappearance of indigenous knowledge and languages, Kirkness suggests that indigenous communities should establish banks of knowledge to preserve their languages and the stories of elders which contain the wealth of their indigenous knowledge system. Storage is of utmost importance, and storage, according to Kirkness, does not have to be fancy or complicated; a tape recorder is a good beginning. Promoting and teaching indigenous knowledge systems in schools will help to not only bring the Igbo indigenous culture and language closer to the younger generation of speakers, but will ensure they gain a firm grasp of the indigenous culture vocabulary items, especially those associated with indigenous knowledge. Incorporating different aspects of the indigenous knowledge system in the teaching of Igbo in the school system will enhance this goal.

Parents also hold the key to the prevention of Igbo from endangerment by bringing up their children to speak Igbo and using it at home. The governments of the five states where Igbo is indigenously spoken should ensure that Igbo is taught and learnt at all tiers of education, from nursery to primary schools and secondary schools to tertiary institutions (both private and public). The government should monitor compliance and mete out punishment to defaulters. Award of scholarships and bursaries to students of Igbo in tertiary institutions will be a great source of encouragement when students studying Igbo at the tertiary level are motivated with scholarships and bursaries. This will attract more students.

All nursery, primary and secondary schools should have weekly activities of Igbo culture, using Igbo language in songs, dances, games, drama, etc. This will enhance Igbo vocabulary learning and retention. Knowledge of one’s indigenous language can be made a pre-requisite for advancement in certain areas, for example: promotion from junior secondary school to senior secondary school. Though many books have been written on Igbo language, many more materials for language education and literacy are required in the language. There is also the need for more materials in everyday media (audio and video recordings) in the language. The Federal Government of Nigeria has a positive statement about the Nigerian indigenous languages but has not taken significant steps to ensuring the practical realization of the language policy statement as enunciated in the Nigerian National Policy on Education.

The preservation of Igbo language and knowledge systems has huge implications not just for the Igbo indigenous-speaking communities, but also for the larger communities outside the indigenous ones. For the Igbo indigenous communities, their unique cultural and linguistic identities will continue to be maintained, sustained and also to enjoy intergenerational transmission. For the larger communities outside the indigenous Igbo ones, the preservation of the Igbo cultural and linguistic heritage will continuously constitute and contribute a valuable source of cultural and linguistic diversity.

Language and Semiotic Studies2020年2期

Language and Semiotic Studies2020年2期

- Language and Semiotic Studies的其它文章

- A Statistical Approach to Annotation in the English Translation of Chinese Classics: A Case Study of the Four English Versions of Fushengliuji1

- Deducing the Intonation of Chinese Characters in Suzhou-Zhongzhou Dialect by Its Singing Technique in Kunqu: A New Probe into Ancient Chinese Phonology

- Aspects of Transitivity in Select Social Transformation Discourse in Nigeria

- Towards Semiotics of Art in Record of Music

- Umwelt-Semiosis: A Semiotic Perspective on the Dynamicity of Intercultural Communication Process

- L3 French Conceptual Transfer in the Acquisition of L2 English Motion Events among Native Chinese Speakers