Management of the late effects of disconnected pancreatic duct syndrome: A case report

Reiko Yamada, Yuhei Umeda, Yasunori Shiono, Hiroaki Okuse, Naoki Kuroda, Junya Tsuboi, Hiroyuki Inoue,Yasuhiko Hamada, Kyosuke Tanaka, Noriyuki Horiki, Yoshiyuki Takei

Abstract

Key words: Case report; Endoscopy; Necrosis; Pancreas; Walled-off necrosis;Disconnected pancreatic duct syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Disconnected pancreatic duct syndrome (DPDS) is characterized by disruption of the main pancreatic duct (MPD), resulting in various upstream pancreatic glands becoming isolated from the MPD downstream[1]. A recent retrospective study reported that DPDS occurred more frequently in patients with walled-off necrosis(WON) than in those with other pancreatic fluid collections (PFCs) (68.3%vs31.7%)[2].It was also reported that DPDS due to WON is disadvantageous compared to that due to other PFCs because of the increased need for re-interventions (30%vs18.5%;P=0.03), rescue surgery (13.2%vs4.8%;P= 0.02), and a longer length of admission[2].However, there have been few reports about the late adverse effects of DPDS.Currently, endoscopic intervention is increasingly considered as a less invasive alternative to surgery for managing DPDS[3]. Thus, endoscopic intervention is considered to be effective for the late effects of DPDS. We describe a case of endoscopic management for the late effects of DPDS with complete duct disruption and pancreatic transection following severe acute pancreatitis.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

An 81-year-old man with a medical history of abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA),hypertension, dyslipidemia, and chronic kidney disease visited our hospital with fever and abdominal pain.

History of past and present illnesses

The patient reported having severe acute necrotizing pancreatitis due to a gallstone 7 years prior. He did not drink alcohol. He was referred to our hospital 42 d after onset because of the development of WON in the pancreatic neck region (Figure 1). The patient underwent endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided drainage and necrosectomy eight times. Subsequently, he recovered from WON, his nutritional status improved,and he was discharged from our hospital after 79 d. After discharge, we performed endoscopic choledocholithotomy. Cholecystectomy was not performed because the gallbladder had already shrunk. Although he had a pancreatic fistula due to pancreatic transection following severe pancreatitis, he had been asymptomatic for 6 years. Four years after WON onset, he underwent distal gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y reconstruction for invasive gastric cancer.

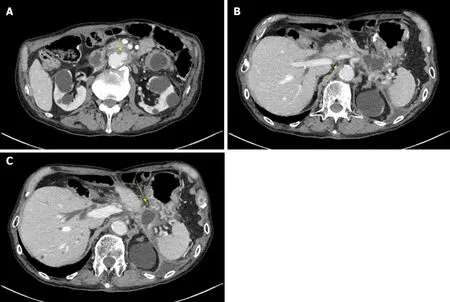

Figure 1 Computed tomography image showing the development of walled-off necrosis in the pancreatic neck region when severe acute necrotizing pancreatitis occurred 7 years prior.

Physical examination

On examination, upper abdominal tenderness and gastrointestinal bleeding were noted.

Imaging examinations

Computed tomography (CT) scan was suggestive of PFC in the pancreatic tail due to pancreatic transection that had spread to the aorta with surrounding inflammation.Inflammation was also found around the aorta and ulcer-like blood flow appeared in the aortic aneurysmal thrombus (Figure 2A). Gastrointestinal bleeding was present,but no active bleeding was observed through the endoscope. The CT scan showed venous dilation mainly around the residual stomach, and it was thought that bleeding occurred from the vasodilator due to splenic vein occlusion (Figure 2B). Because there was a risk of rupture of the AAA owing to the spread of inflammation from the PFC,drainage was deemed necessary.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

The final diagnosis of the presented case is late effects of DPDS and infected PFC due to severe acute pancreatitis and WON.

TREATMENT

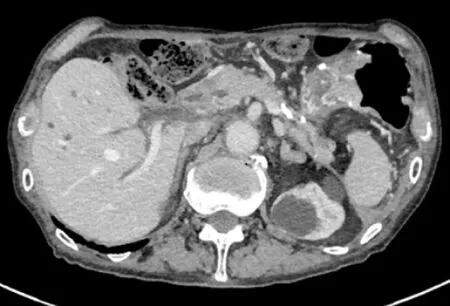

First, we attempted transpapillary drainage via double-balloon endoscopy (DBE) due to difficulty in EUS-guided puncture secondary to venous dilation around the residual stomach and the distribution of the PFC, which was extensive but narrow around the stomach (Figure 2C). DBE retrograde pancreatography showed complete pancreatic duct disruption (Figure 3). Pancreatic duct drainage failed because of complete MPD disruption. Thereafter, we performed EUS-guided drainage. The linear array echo-endoscope showed many vessels surrounding the PFC and stomach. We punctured the PFC using a 19-gauge needle, carefully avoiding the vessels and inserted a double pig catheter (6 French/4 cm) transmurally (Figure 4). After transmural drainage, the inflammation was resolved and stenting for the AAA was performed successfully.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The inflammation further improved after the procedure (Figure 5). The patient has been free from WON infection for more than 2 years after the procedure.

DISCUSSION

Figure 2 Computed tomography scan taken at 7 years after severe acute necrotizing pancreatitis. A: Computed tomography (CT) scan showing spread of the pancreatic fluid collection to the aorta with surrounding inflammation and the appearance of ulcer-like blood flow in the aortic aneurysm thrombus (yellow arrow); B:The CT scan also shows splenic vein occlusion (yellow arrow; B) and venous dilation around the residual stomach; C: The shape of the pancreatic fluid collection is narrow around the stomach (yellow arrow), although it shows extensive spread.

Previously, surgery was the first therapeutic choice for DPDS. Fischeret al[4]retrospectively reviewed operated cases of DPDS; distal pancreatectomy had been performed in whole delayed DPDS cases. They concluded that fluid collection often is not accessible endoscopically and that no long-term data support the patency of the endoscopic approach. However, endoscopic intervention is increasingly considered as a less invasive alternative to surgery in the management of DPDS[3]. Furthermore,guidelines were developed for endoscopic management of acute necrotizing pancreatitis, including the management of DPDS[5].

There are two endoscopic strategies for treating DPDS: Transpapillary placement of the drainage stent and endoscopic transmural drainage of the PFC. The evidencebased multidisciplinary guidelines of the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy suggested that transpapillary stenting can be considered where partial MPD disruption has occurred[5]. Even though widely practiced in the management of DPDS, transpapillary stenting sometimes results in failure. However, successful transmural drainage does not depend on the presence of communication between the proximal MPD and the disconnected upstream segment. Banget al[6]reported that the best indication of EUS-guided drainage for DPDS is when WON or PFC is larger than 4 cm at its largest dimension and located within 15 mm of the gastrointestinal lumen.In this case, the PFC distribution was narrow and surrounded the stomach, although it had spread extensively. Thus, we attempted to perform transpapillary drainage first but discontinued the drainage because of complete MPD disruption. Although the width of the PFC was less than 4 cm, transmural drainage was performed safely and successfully.

The present patient showed recurrence of pancreatitis in the form of PFC after a prolonged period of 7 years. Recurrence in the form of a necrotic cavity or pseudocyst has been reported in approximately 10% of patients, even after successful endoscopic treatments. For WON, the recurrence rates were reported to be 9.4% after endoscopic transmural drainage (the single or multiple transluminal gateway technique) in 53 patients[7], 7.8% after combined percutaneous and endoscopic drainage in 103 patients[8], and 10.9% (7%-15%) after endoscopic necrosectomy in a meta-analysis (8 studies, 233 patients)[9]. Although few reports have described the recurrence interval of pancreatitis, Yasudaet al[10]reported that 7.0% of 43 patients showed recurrence within 2-8 months after endoscopic treatment.

CONCLUSION

Figure 3 Pancreatogram during a double-balloon endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography shows complete pancreatic duct disruption (yellow arrow).

Based on the literature, it might be rare for recurrence to occur more than 5 years later. Nevertheless, it is important to continue following patients after the treatment of WON with pancreatic transection because late recurrence due to DPDS may occur.

Figure 4 Endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage. A: A linear array echo-endoscope shows many vessels surrounding the pancreatic fluid collection and stomach;B, C: The pancreatic fluid collection is punctured using a 19-gauge needle, carefully avoiding the vessels (B), and a double pigtail catheter (6 French/4 cm) is inserted transmurally (C).

Figure 5 The inflammation further improved after the procedure.

World Journal of Clinical Cases2019年9期

World Journal of Clinical Cases2019年9期

- World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Evaluation and management of acute pancreatitis

- Rituximab-induced lgG hypogammaglobulinemia in children with nephrotic syndrome and normal pre-treatment lgG values

- Causes associated with recurrent choledocholithiasis following therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: A large sample sized retrospective study

- Laparoscopic appendectomy for elemental mercury sequestration in the appendix: A case report

- Sofosbuvir/Ribavirin therapy for patients experiencing failure of ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir + ribavirin therapy: Two cases report and review of literature

- Nerve coblation for treatment of trigeminal neuralgia: A case report