Clinical Benefit of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor-Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Plus Radiotherapy for Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor-Mutated Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Retrospective Analysis on Real World Data

Wang Ranlin, Li Tao, Lv Jiahua, Sun Chang, Shi Qiuling

Department of Oncology, The Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University, Luzhou 646000, Sichuan, China (Wang Ranlin, Li Tao, Sun Chang, Shi Qiuling); Department of Radiation Oncology, Sichuan Cancer Hospital & Institute, Sichuan Cancer Center, School of Medicine, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu 610041, China (Wang Ranlin, Li Tao, Lv Jiahua, Sun Chang); Department of Symptom Research, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Blvd.Houston, Texas 77030, USA (Shi Qiuling)

[Abstract] Objective: To investigate the benefit of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) with radiotherapy in patients with EGFR mutation-positive metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), compared with TKIs alone. Methods: A total of 103 patients with stage Ⅳ EGFR-mutated NSCLC treated from February 2015 to May 2017 at Sichuan Cancer Hospital were analyzed retrospectively. Fifty patients were treated with EGFR-TKIs (gefitinib or erlotinib) plus radiotherapy (the TKI+RT group) and 53 patients received EGFR-TKIs alone (the TKI group). Tumor response, survival and toxicities were compared between the two groups. Results: Median follow-up time was 11.7 months (2.8-36.3 months). The overall response rate (ORR) and disease control rate (DCR) in the TKI+RT group vs the TKI group were 62% vs 37.7% (P=0.014) and 88% vs 75.5% (P=0.101), respectively. The median progression-free survival (PFS) and median overall survival (OS) in the TKI+RT group were superior to those of the TKI group (18.87 months vs 12.80 months, P=0.035 and 23.10 months vs 18.30 months, P=0.011). OS rates in the TKI+RT group and the TKI group were 56.0% vs 35.8% at year 1 (P=0.04) and 16.0% vs 3.8% at year 2 (P=0.036). Multivariate Cox model found that TKI+RT related to significantly better OS (hazard ratio=0.209; 95% CI, 0.066 to 0.661; P=0.008) than TKI alone. Adverse events did not differ significantly between the two groups (P>0.050). Conclusion: Compared with EGFR-TKIs alone, EGFR-TKIs combined with radiotherapy was well tolerated and showed benefit in tumor response and survival for EGFR mutation-positive metastatic NSCLC patients.

[Key words] Radiotherapy; Non-small cell lung cancer; Epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor; Effectiveness

INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer is a malignant tumor with the highest morbidity and mortality among cancers worldwide. According to data from the National Cancer Center of China in 2017, there are 0.78 million new cases of lung cancer and 0.63 million deaths worldwide annually[1]. Non-smallcell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for 80%-85% of lung cancers and includes adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), adenosquamous cell carcinoma and large cell carcinoma[2]. Distant metastasis occurred in approximately 45%-55.8% of NSCLC patients with a 5-year survival rate of <5%[3-6].

Molecular testing and analysis of biomarkers, such as EGFR, ALK and ROS-1, are recommended for metastatic NSCLC.The presence of activating mutations in the EGFR gene is currently the best predictor of the therapeutic efficacy of epidermal growth factor receptortyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs) in patients with advanced-stage NSCLC[7]. Sakurada et al. and Eberhard et al. showed that the frequency of activating EGFR mutations ranges from 60% to 80%, and this mutations predominantly occur in Asians, females, patients with adenocarcinoma histology and nonsmokers[8]. The most common mutation types found are several deletions in EGFR exon 19 and one substitution in EGFR exon 21 (L858R). For EGFR-mutant NSCLC patients, first-line systemic treatment with EGFR-TKIs, such as gefitinib or erlotinib, is recommended from NCCN guidelines Version 6.2018. In contrast, the efficacy of platinum-based first-line chemotherapy for advanced NSCLC is limited, reporting an overall survival (OS) of only 6-10 months due to toxicity and drug resistance[9]. Several randomized controlled studies, including BR.21, IPASS, NEJ002, WJTOG3405, EURTAC and OPTIMAL have also confirmed that both the shortand longterm effect of EGFR-TKIs on EGFR sensitive-mutation patients are significantly better than that of platinum-based first-line chemotherapy[10-16].

Despite the high response rate and prolonged OS of patients with EGFR mutations treated with gefitinib or erlotinib, there are still major clinical obstacles. For instance, the local control rate is still low (only 19.4%-58%), with first-line treatment using EGFR-targeted therapy[10-12, 14-16]. In addition, due to the highly adaptive and mutagenic characteristics of tumors, drug resistance has appeared in nearly all patients after a certain period of time. Specifically, T790M resistance mutations may be the main cause of acquired resistance. After targeted therapy, the main recurrent sites are original tumor sites (including primary and metastatic sites), as opposed to sites of metastasis[17]. Ultimately, the progression-free survival (PFS) of most EGFR mutation-positive patients has failed to exceed 12-14 months[18]. Therefore, the greatest challenge of using TKIs is how to control the recurrence in original tumor sites.

For patients with metastatic NSCLC, NCCN guidelines Version 6.2018 recommend that palliative external irradiation therapy be administered if the patient’s Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) score is 0-1 or the patient has pain, fracture and other local metastasis symptoms.Previous phase Ⅱ clinical trials indicated that radiotherapy (RT) combined with EGFR-TKI targeted therapy may become a promising new way to solve the problems in locally advanced (stage Ⅲa/b) NSCLC patients[19]. However, data regarding RT combined with EGFR-TKI for patients with stage Ⅳ EGFR-mutant NSCLC are scarce[20,21]. Thus, using the real world data, we conducted a retrospective controlled study to investigate the tumor response, survival and safety of EGFR-TKIs combined with RT compared to EGFR-TKIs alone for EGFR-mutated metastatic NSCLC. Our hypothesis is that RT combined with EGFR-TKIs has a positive effect on both local tumor control and remote effects, and will improve survival for patients with stage Ⅳ EGFR-mutant NSCLC.

METHODS

Study design and participants

We retrospectively screened 872 patients treated at our hospital from February 2015 to May 2017 among whom 103 met the eligibility criteria and were included in the study. The study included patients with stage Ⅳ NSCLC, as confirmed by pathological and image analysis. None of the patients had received molecular targeted therapy other than EGFR-TKIs(patients receiving either EGFR-TKIs targeted therapy or EGFR-TKIs targeted therapy combined with RT were included). Eligible patients were required to be 18-80 years of age, harbour an EGFR mutation, present with metastases in other organs, have adequate haematological and biochemical values (neutrophil counts>1.5×109/L, platelet counts>100×109/L, haemoglobin>10g/L), voluntarily accept EGFR-TKIs as treatment and decide to continue or terminate the treatment according to their wishes. Exclusion criteria included uncontrolled complications, uncontrolled liver or kidney dysfunction, clinical stage Ⅰ-Ⅲ, severe cardiopulmonary disease, impairment of gastrointestinal function or gastrointestinal disease that may significantly alter EGFR-TKI absorption, and pregnancy or lactation. The inclusion criteria for RT were: 1.Patients with intrapulmonary metastasis received RT at pulmonary lesion and positive lymph nodes with biological dose≥50Gy. 2. Patients with brain metastasis received whole brain RT (WBRT) with biological dose≥30Gy. 3. Patients with bone metastasis receivedRT in metastatic lesions with biological dose≥30Gy, and pleural metastasis received RT in metastatic lesionswith biological dose≥60Gy. Radiation methods consisted of both conventional fraction and Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy (SBRT). This study was undertaken in accordance with the ethical standards of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. A waiver of informed consent was requested, and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of our hospital.Patients were assigned toreceived both RT and EGFR-TKIs (the TKI+RT group) and EGFR-TKIs alone (the TKI group).

Treatment

In the TKI group, patients received EGFR-TKIs alone until disease progression or the development of intolerable toxicities. EGFR-TKIs included erlotinib, 250 mg/d, (Tarceva, Roche, Registration number: H20120102) or gefitinib, 150 mg/d, (Iressa, AstraZeneca Plc, Registration number: H20070165). In the TKI+RT group, erlotinib or gefitinib were administered concomitantly with RT throughout the course of treatment. A total of 23 (46%) patients with brain metastasisin the TKI+RT group received WBRT which was delivered at a dose of 30-40 Gy/10f for 5 days per week, up to 2 weeks.And 17(34%) of them with residual lesions received another 4 Gy×3f after WBRT. In addition, 19 (38%) patients received RT for bone metastases at a dose of 30-39 Gy/10-13f, and 17 (34%) patients received thoracic RT (including primary lung lesions and positive lymph nodes) at a dose of 1.5-3 Gy, with an accumulated dose of 50-70 Gy. One (2%) patient received RT for pleural metastases at a dose of 2.5 Gy/f and an accumulated dose of 68.5 Gy.

Criteria for clinical outcomes

Patients’ demographic, neoadjuvant treatment, toxicity and follow-up results were retrieved from medical records and the follow-up system and reviewed in detail. Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) 1.1 criteria was utilized to assess the effectiveness within the fourth week (from Monday to Sunday) after radiotherapy, including complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), progressive disease (PD), objective response rate [ORR, percentage of (CR+PR) patients of the entire group] and disease control rate [DCR, percentage of (CR +PR+SD) patients of the entire group]. However, bone metastasis is non-measurable, and its evaluation criteria include pain evaluation and quality of life evaluation (pain scale was based on WHO’s pain grading criteria, and activity level scale was based on ECOG score standard). CR referred to the bone pain decreased by ≥grade 2 or the activity level increased by ≥grade 2; PR referred to the bone pain decreased by grade 1-2 or the activity level increased by grade 1-2; SD referred to the bone pain decreased by grade 0-1 or the activity level increased by grade 0-1;PD referred to the aggravation of bone pain or the decline of activity level[22-23]. PFS referred to the time from treatment to PD, and OS referred to the time from diagnosis to death from any cause or the last follow up. Treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) were assessed weekly during the treatment, using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v.4.03. TRAEs were recorded from the start of the first course of radiation or the first dose of EGFR-TKI until treatment discontinuation.

Follow up

We conducted follow up at most every 1-3 months for the first 2 years and every 6 months thereafter. If there was a change in the patient’s condition, the follow-up time was usually at any time or 1 month, otherwise it was 3 months. Follow-up items included contrast-enhanced CT/MRI/color ultrasound/hematology examination etc.

Statistical analysis

The chi-square test was applied for the comparison of categorical variables, including patient characteristics and the therapeutic response rate between two groups. PFS and OS were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method, and subgroup survival curves were plotted with the time of observation on the horizontal axis and the survival rate on the vertical axis; each time point was connected to its corresponding survival rate. The survival time was compared between groups using the log-rank test. Multivariate Cox regression models were employed toestimate the prognostic effect of TKI+RT, compared to TKI alone, with adjustment of confounders, such as age, hepatic metastasis,EGFR mutation status. All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS software (version 19, IBM Corp. Armonk, NY, USA). Two-tailed tests were performed, andP<0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patients’ characteristics

Data of 103 patients with metastatic NSCLC were analyzed. Patients were divided into two groups: the TKI+RT group (n=50) and the TKI group (n=53). Baseline clinical characteristics of the 103 patients are listed in Table 1. The median ages of the TKI+RT group and the TKI group were 58.76 (34-79) years and 58.30 (34-76)years, respectively; and the majority of patients in both groups (70%vs62.3%) underwent first-line therapy. Although more patients in the TKI+RT group harbored L858R mutation in exon 21 compared to those in the TKI group (60.0%vs43.4%), the difference did not show a statistical significance (P=0.09). There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups with regard to ECOG score, age, sex, EGFR gene mutation type, type of EGFR-TKI, and metastatic organ (P> 0.05).

Table 1. Characteristics of the Patients

†Included adrenal gland,rectum,scalp, pancreas, andpericardium.

TKI: tyrosine kinase inhibitor; RT: radiotherapy; EGFR: epidermal growth factor receptor;ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group;PS: performance status.

Clinical response

The cut-off date for this retrospective analysis was August 1, 2018, and the median follow-up time was 11.7 (2.8-36.3)months. In the TKI+RT group (n=50), CR was achieved in 4 patients (8.0%), PR in 27 (54.0%), SD in 13 (26.0%), and PD in 6 (12.0%),with an ORR of 62.0% and DCR of 88.0%. In the TKI group (n=53), CR was achieved in 2 patients (3.8%), PR in 18 (34.0%), SD in 20 (37.7%), and PD in 13 (24.5%), resulting in an ORR of 37.7% and DCR of 75.5%. As is shown in Table 2, the difference between the two groups was statistically significant in ORR (P=0.014), but not in DCR (P=0.101).

Table 2. Clinical Activity Summary

†Complete response+partial response.

*Complete response+partial response+stable disease for at least 8 weeks.

CR: complete remission; PR: partial response; SD: stable disease; PD: progressive disease.

Survival outcomes

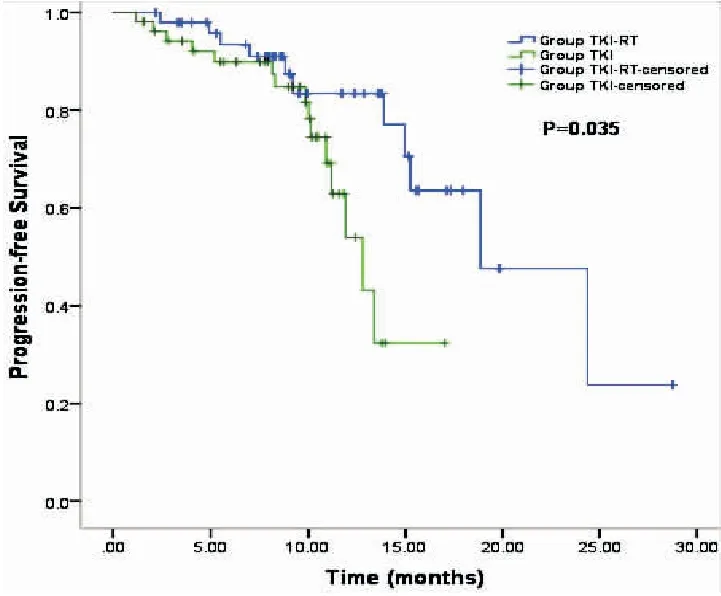

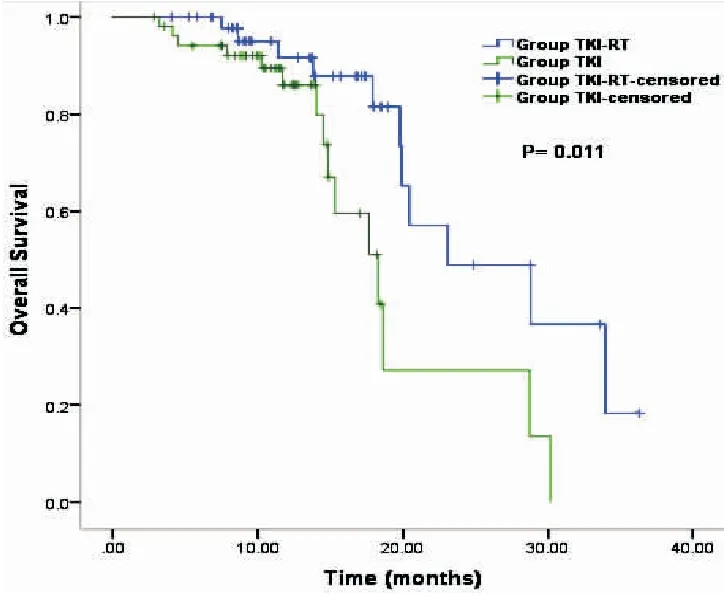

The median PFS in the TKI+RT group was superior to that in the TKI group (18.87 monthsvs12.80 months,P=0.035, Figure 1). In addition, the median OS was 23.10 months in the TKI+RT group compared with 18.30 months in the TKI group (P=0.011, Figure 2). OS rates in the TKI+RT group and the TKI group were 56.0% and 35.8%at 1 year (P=0.04) and 16.0% and 3.8% at 2 years (P=0.036), respectively.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier Survival Curves Indicating Progression-Free Survival in the TKI+RT Groupvsthe TKI Group

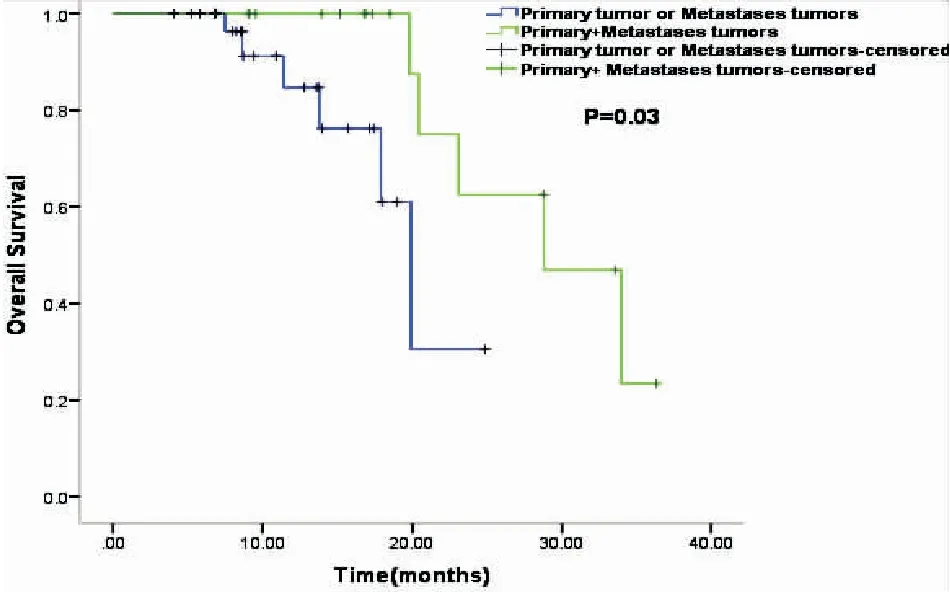

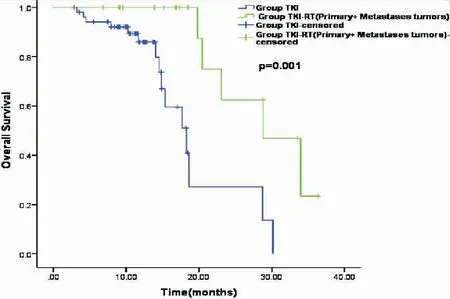

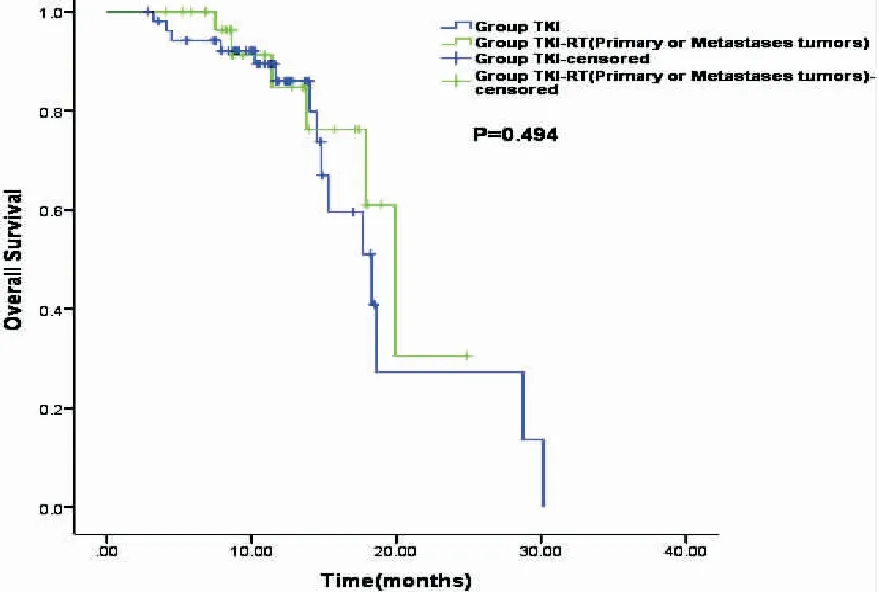

In the TKI+RT group, 18(36%) patients received RT for primary tumor plus metastatic tumors (the P+M group), and 32 (64%) patients received RT for either primary tumor or metastasis (the P/M group). The subgroup analysis showed that the median OS in the P+M group was significantly longer than that in the P/M group (28.80 monthsvs19.90 months,P=0.03, Figure 3), and also significantly longer than that in the TKI group who received no RT (28.80 monthsvs18.30 months,P=0.001, Figure 4). The median OS of patients with RT to either primary or metastasis in the TKI+RT group was 19.90 months compared with 18.30 months in the TKI group (P=0.49, Figure 5).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Survival Curves Indicating Overall Survival in the TKI+RT Groupvsthe TKI Group

Figure 3.Kaplan-Meier Survival Curves Indicating Overall Survival in the P+M Groupvsthe P/M Group.

Figure 4.Kaplan-Meier Survival Curves Indicating Overall Survival in the P+M Groupvsthe TKI Group

Figure 5.Kaplan-Meier Survival Curves Indicating Overall Survival in the P/M Groupvsthe TKI Group

Overall, the ORR was improved by 24.3% (P=0.014), and the median OS and median PFS increased by 4.80 months (P=0.011) and 6.07 months (P=0.035) in the TKI+RT group compared with the TKI group. Of note, with adjustment of potential prognostic factors (e.g.: age, hepatic metastasis), multivariate analysis demonstrated that TKI+RT demonstrated almost 5 times OS benefit (HR=0.209, 95%CI,0.066 to 0.661;P=0.008) compared with TKI only, as summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Univariate and Multivariate Analyses Demonstrating Factors Associated with Overall Survival

SubgroupUnivariateanalysisMultivariateanalysisHR(95%CI)PHR(95%CI)PGroup TKI1.0001.000 TKI+RT0.352(0.153to0.809)0.0140.209(0.066to0.661)0.008Age,y <601.0001.000 ≥600.582(0.262to1.290)0.1820.260(0.092to0.736)0.011Sex Male1.0001.000 Female1.258(0.560to2.828)0.5780.823(0.277to2.443)0.725EGFRmutationstatus 19Del1.0001.000 21L858R0.713(0.322to1.581)0.4050.538(0.205to1.411)0.208EGFR-TKI Erlotinib1.0001.000 Gefitinib1.349(0.620to2.937)0.4511.938(0.622to6.039)0.254BrainMetastases No1.180(0.533to2.608)0.6830.978(0.322to2.968)0.969 Yes1.0001.000IntrapulmonaryMetastases No0.646(0.264to1.585)0.3400.315(0.087to1.143)0.079 Yes1.0001.000BoneMetastases No1.001(0.453to2.210)0.9980.989(0.333to2.933)0.983 Yes1.0001.000LiverMetastases No0.368(0.122to1.108)0.0750.195(0.038to1.002)0.050 Yes1.0001.000PleuraMetastases No0.904(0.356to2.297)0.8331.347(0.320to5.668)0.684 Yes1.0001.000OthersMetastases No0.498(0.065to3.815)0.5020.681(0.051to9.087)0.771 Yes1.0001.000Beforetreatment Untreated1.0001.000 Chemotherapy0.895(0.352to2.273)0.8151.431(0.370to5.537)0.604 Surgery2.053(0.446to9.441)0.3553.921(0.558to27.550)0.170ECOGPSscore 0-11.0001.000 21.040(0.348to3.101)0.9450.679(0.151to3.054)0.614Smokinghistory No0.701(0.313to1.567)0.3861.243(0.390to3.963)0.713 Yes1.0001.000

Abbreviations as in Table 1.

Safety

Acute side effects are summarized in Table 4. Most were in grade 1-2 and well controlled by supportive care. Adverse events did not differ significantly between the two groups during therapeutic process.

Table 4.Adverse Events during Therapeutic Process

AdverseeventTKI+RT(n=50)n(%)TKI(n=53)n(%)PNauseaandvomiting Grade1-214(28.00)12(22.64)0.532 ≥Grade31(2.00)0(0.00)0.977Myelosuppression Grade1-214(28.00)13(24.53)0.689 ≥Grade31(2.00)0(0.00)0.450Impairedliverfunction Grade1-29(18.00)12(22.64)0.560 ≥Grade30(0.00)0(0.00)1.000Rash Grade1-219(38.00)18(33.96)0.669 ≥Grade32(4.00)1(1.89)0.959Diarrhoea Grade1-29(18.00)11(20.75)0.724 ≥Grade30(0.00)1(1.89)1.000Radiationpneumonitis AnyGrade3(6.00)0(0.00)1.000

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge,this is the first relatively large-scale retrospective study to directly compare the survival outcomes of EGFR-TKI combined with RT (including primary tumor and organ-specific metastasis) versus EGFR-TKI alone for EGFR-mutated metastatic NSCLC patients (mostly those with bone and brain metastases).Our study showed that both the short-term results and survival were superior in the TKI+RT group than in the TKI group for stage Ⅳ EGFR-mutated NSCLC patients. Overall, the ORR was improved by 24.3% (P=0.014), and the median OS and median PFS increased by 4.80 months (P=0.011) and 6.07 months (P=0.035) in the TKI+RT group compared with the TKI group. The survival outcomes are similar to Paolo Borghetti’s multicentric analysis in that the median OS was 23 months in metastatic EGFR-or ALK-mutated NSCLC patients who was treated with EGFR-TKI plus RT[21]. But unlike our study, theirs mainly focused on the chronological order of RT and EGFR-TKI treatment, and the short-term results were not analyzed. In this study, some of the patients enrolled had two or more metastatic sites in the TKI-RT group(e.g. brain metastasis with bone metastasis, brain metastasis with intrapulmonary metastasis, etc.). Subgroup analysis of a single RT site was performed with low accuracy. Therefore, our subgroup analysis was based on the number of patients’RT sites. The results showed that patients receiving RT for primary lung lesions plus metastasis achieved better survival outcomes both than patients receiving RT for either primary lesions or metastasis (P=0.03) and patients not receiving local RT (P=0.001). Similar to Qinghua’s study, we conducted subgroup analysis according to the location of radiotherapy[20]. However, they mainly focused on the consolidative local ablative therapy including surgery, RT combined with EGFR-TKIs targeted therapy, while we just involved patients receiving merely RT combined with EGFR-TKIs,so as to better study the effect of RT. The median OS in the P/M group was 19.90 months compared with 18.30 months in the TKI group. However, local RT for either primary or metastasis combined with EGFR-TKIs did not significantly increase overall survival compared with EGFR-TKIs alone. And, the difference in DCR was not significant (P=0.101). This may due to the limited sample sizes, indicating the need for a larger sample in future research.After adjustment of potential prognostic factors by multivariate analysis (Cox regression model), TKI+RT demonstrated almost 5 times OS benefit compared with TKI only.

There were several clinical trials focused on integrating EGFR-TKI targeted therapy and RT in advanced (stage Ⅲa/b-Ⅳ) NSCLC patients,whose results were controversial. SWOG 0023 and CALGB30106 showed that the combination of RT and chemotherapy with EGFR-TKIs did not bring survival benefits[24]. EGFR-TKIs should be avoided after chemoradiotherapy and consolidation chemotherapy in unselected EGFR status and stage Ⅲb NSCLC patients. However, some other studies obtained encouraging results. CALGB30605 (RTOG0972) enrolled 75 patients with stage Ⅲ a/b NSCLC who received thoracic RT combined with erlotinib targeted therapy after two cycles of induction chemotherapy[19]. The median PFS, OS and 12-month OS rate were 11 months, 17 months and 57%, respectively, showing a satisfactory treatment effect. Moreover, a few trials reported that stereotactic radiosurgery combined EGFR-TKI was also a feasible and tolerable option for brain oligometastatic metastases NSCLC patients[8,25-27]. Zhen Wang, et al.reported 14 retrospectively analyzed NSCLC patients with disease progression after platinum-based chemotherapy regimens, of whom 86% had stage Ⅳ disease[28]. The patients underwent primary lung lesion SBRT and gefitinib 250 mg once daily from one week before the start of SBRT. The median PFS and OS were 7.0 and 19.0 months, showing that SBRT combined with gefitinib was a promising treatment strategy for advanced NSCLC after the failure of previously administered chemotherapy.

Compared with the research mentioned above, our research has several advantages. First, most patients in previous studies were in unknown EGFR mutational status, which may significantly affect the treatment effect and prognosis. To avoid this, our study included patients with confirmed activating EGFR mutation (exon 19 deletion or exon 21 L858R mutation). Second, those studies were all retrospective single-arm studies that did not directly compare the effect of EGFR-TKI combined with RT with that of EGFR-TKI alone. Because the sample sizes were too small in studies above, there were no subgroup analyses of stage Ⅳ patients, and significant heterogeneity between data sources was noted. Our study is the first relatively large sample scale to study patients with stage Ⅳ EGFR-mutant NSCLC. Although previous studies have suggested that the efficacy of RT combined with EGFR-TKI is controversial, our study provided scientific evidence to support the clinical benefits of this treatment modality. In addition, it may also inspire further exploration of the optimal time and mode for combining RT with EGFR-TKI in stage ⅣEGFR-mutant NSCLC patients. In our study, the general condition of the patients was relatively good. During radiotherapy intervention, about 34 patients (68%) were patients with good systemic state control of the disease (including patients with oligoprogression or oligostasis, and patients with stable systemic state control of TKI treatment). The systemic control of the remaining 16 patients (32%) was not ideal, but some patients presented local symptoms, such as pain and fracture. In order to alleviate local symptoms and improve the quality of life, timely intervention was also chosen when TKI and radiotherapy were taken.

Although it remains unclear why additive interaction between EGFR-TKIs and radiation (particularly high-dose fraction radiation) is superior to TKI alone for patients with stage Ⅳ NSCLC, some hypotheses have been reported. For one thing, EGFR-mutant NSCLC cells exhibited delay in the repair of radiation induced DNA double-strand breaks,and the function could be blocked using TKI or monoclonal antibodies (mAb)[29]. Furthermore, it has been reported that EGFR-TKIs, such as gefitinib and erlotinib, could enhance the radiosensitivity of tumor cells by blocking the cell cycle and accelerating apoptosis and DNA damage repair[30-31].Therefore, tumors with an EGFR mutation may be more sensitive to radiation than their wild-type counterparts[31-32].

For another thing, some studies suggest that repeated radiation exposure may lead to increased EGFR expression and activated EGFR signalling pathway[33].In this situation, EGFR-TKI could inhibit radiation-induced activation of EGFR[31]. Therefore, the combination of RT with EGFR-TKI appears a biologically rational and highly promising avenue for cancer research. However, little is known about how EGFR-mutant NSCLC with acquired resistance to TKIs responds to radiation actually, and further research is still needed[34].

Besides, the adverse events of our study were manageable and most of them were in Grade 2.Among the 17 patients received thoracic radiotherapy, grade 3 pneumonitis occurred in one patient, and no other serious adverse events were reported. The addition of gefitinib or erlotinib to RT was generally well tolerated.

There are several limitations of our study that should be acknowledged. First, this was a retrospective study in a single institution, although the patient cohort well presented the whole group of patients with stage Ⅳ NSCLC. Second, although our sample size was larger than those of previous studies, it was not large enough to detect statistical difference in some subgroups. In our study, 15 patients (30%) in group TKI-RT experienced second-line treatment. Due to the small sample size and the fact that the 15 patients had different metastatic sites and different treatment methods (different ways of operation or different chemotherapy regimens), the influencing factors were mixed, which may affect the accuracy of the analysis results. In order not to cause misunderstanding, the second-line treatment patients were not further analyzed. Third, it has been reported that age, gender, ECOG PS score, EGFR mutation status, EGFR-TKI, brain metastases, intrapulmonary metastases, bone metastases, liver metastases, pleura metastases, previous treatment and smoking history were included in the multivariate analysis. Due to the small sample size of this study, multivariate analysis was mainly used to adjust the potential prognostic factors. Although univariate analysis showed that P>0.1, these factors were considered clinically to affect the prognosis and were included in the multivariate analysis.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our retrospective study demonstrated that RT combined with EGFR-TKI was superior to EGFR-TKI monotherapy in patients with advanced EGFR mutation NSCLC, in terms of tumor response and survival. Future clinical trials and prospective studies to confirm this strategy are warranted.

DISCLOSUREOFINTEREST

The authors declare that they have no potential conflict of interest relevant to this article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the patients, their families, and all of the investigators who participated in the study.