斯里兰卡

——以建筑重新介入

阿诺玛·佩里斯/Anoma Pieris

黄华青 译/Translated by HUANG Huaqing

随着20世纪中叶至后半叶第一代在国外接受训练的斯里兰卡建筑师回国,一种独特的“斯里兰卡式建筑”的主导权确立和自我表达逐步成为可能,一个新的建筑流派也随之创立。“去殖民化”建筑呈现出多种形式,折射出1948年斯里兰卡从英国独立后经历的剧烈社会变迁。政府机构和公共纪念物倾向于唯佛教美学独尊,这一趋势随着古代城市的考古发掘以及殖民和国家层面的文化价值主张而不断增长。受到官方社会主义者的实用主义和民间涌现的城市中产阶级的推动,欧洲现代主义被引入地方语境之中。中国援建的斯里兰卡第一座国际会议中心,举办了1976年不结盟国家首脑会议。这座建筑的几何造型就源于佛教美学。先锋建筑师则将现代主义者的空间与气候适应性设计相结合。

1980年代,随着政府和民用建筑的去殖民化,地域主义的涌现标志着审美趋势的显著转向。从乡土建筑中汲取的本地母题重新定义了一种斯里兰卡式美学,很大程度也归功于阿卡汗建筑奖的宣传平台,当地建筑师的作品得以在国际上发表。这是南亚与东南亚地区去殖民化的全盛时期,针对建筑的角色形成卓有成效的对话,各个国家独有的设计思想体系也得到长足发展。

1国际紧急救援组织儿童村,贾夫纳,斯里兰卡/SOS Children's Village, Jafina, Sri Lanka(摄影/Photo: Sumangala Jayatillaka)

根据这一历史脉络,我们可将斯里兰卡的建筑发展分为3个时期。第一个时期是去殖民时期,如上所述,表现为民族和文化母题的强化。第二个时期始于1977年的经济自由化,在斯里贾亚瓦德纳普拉科特建立了新首都和议会,以取代科伦坡(殖民时期首都)作为国家的行政中心,并开启郊区土地的开发进程。政府主导的城市更新及农村社会住宅项目主要依赖境外援助。然而,5年之后,这个国家因1983-2009年内战而土崩瓦解。设计美学天赋大多只能转向酒店业建筑,这类建筑与城市商业项目之间亦分道扬镳。或许是战时狭隘心理的趋使,设计文化几乎集中体现于精英住宅和旅游产业,它们所呈现出的典型空间远比那些更具社会敏感度的建筑要多。在旅游区的泡沫之外,交战区的暴力和穷困并未消减。商业开发项目大多采取大型体块,填满了那些密度原本很低的郊区空间。

战争的影响在城市密度的不断提升中显而易见,城市住宅的封闭性越发增强,多层公寓层出不穷,以安置因战争而流离失所的难民。公共空间被路障包围,公共生活被交战状态及军国主义化统治所侵蚀。灾害不断的氛围集中体现在2004年印度洋海啸,它摧毁了沿海地区的村庄和城镇。因海啸赈灾而注入的国际援助引发一系列社会导向的住宅项目的重现。

本专辑提及的建筑师都属于第三个时期,也就是2009年内战结束之后。建筑活动日益活跃。面临的主要挑战包括重建被战争所破坏的北部及东部地区,重新安置以泰米尔人和穆斯林为主的少数族裔。其中,苏曼加拉·贾雅提拉卡设计的贾夫纳国际紧急救援组织儿童村(图1,见24页)是一个重要的社会导向性项目。它延续了由国际非政府组织在斯里兰卡和其他贫困或新兴经济体建造的类似孤儿院模式,这些国际组织已发展出一种十分成功的社会服务供给模型。贾雅提拉卡之前也曾在斯里兰卡的其他地区为国际紧急救援组织设计项目,每个项目的设计思路都是力争延续当地乡土文脉——这也是国际组织的要求——以确保儿童村可以无缝融入其所在的环境。在将这种思路转译为建筑语言的过程中,他重新创造了一种村落肌理,令人想起孩子们所熟悉的农业村庄——这些村庄依然可透过建筑周围的“自然(植物的)格栅”隐隐瞥见,只不过这组建筑中的“房子”比周围那些要坚实得多。鉴于战后孤儿数量如此之多,这座饱含情感的建筑确保了家庭在社区中的安全感,也回应了重新融入社会的需求。

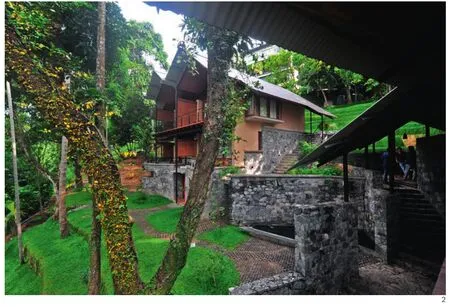

稳健建筑工作室通过酒店类项目探索空间的延续性。他们在山城康提设计的精品酒店(图2,见 28页)并不像一栋孤立建筑,而是城市与山景的一个自然、谦恭的延伸。建筑顺应了陡峭的地形,面朝湖光山色。建筑群盘旋上升,无视形式或材料设计的限制;其轻质钢结构类似于非正式的城市或工业构筑物,与建筑的形式操作浑然一体。建筑时而攀上山坡,时而毫无戒备地敞向街侧——这种方式使人联想到康提的乡土建筑,但绝未流于殖民或文化取向建筑的形式几何学。米琳达·帕蒂拉贾和他的团队抛弃了过去充斥着酒店类建筑的如画风格的僵化历史。

2 精品酒店,康提,斯里兰卡/Boutique Hotel, Kandy, Sri Lanka(摄影/Photo: Kolitha Perera)

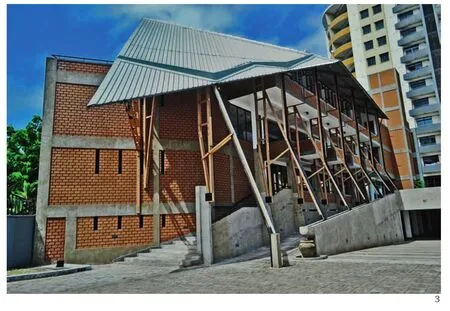

3 内隆艺术中心,科伦坡,斯里兰卡/Nelung Arts Centre, Colombo, Sri Lanka(摄影/Photo: Kesara Rathnavibhushana)

4马内尔住宅,科伦坡,斯里兰卡/Manel Nivasa, Colombo,

Sri Lanka(摄影/Photo: Eresh Weerasuriya)

希兰特·韦兰达维设计的两个项目皆位于商业首都科伦坡的狭窄城市地段。内隆艺术中心(图3,见34页)是一座教育和表演艺术设施,它通过在拥挤的城市区域嵌入休闲与公共活动空间,延续了上述社会融入的动议。这座4层高的建筑采取L型平面布局,环抱一片开放广场,面朝广场的阳台由多层垂直木桁架所包裹。建筑形式明显传达出一种为公众参与创造空间的张力;它的灵感来源是,当地传统表演一般都在开放空间举行,以此吸引更多的大众观看;这个设计也正是为了促进城市中的类似互动。

建筑师的另一个项目是马内尔住宅(图4,见38页),业主是一位来自农村、白手起家的商人,同时是一位虔诚的僧伽罗佛教徒。建筑师的灵感来自当地村民熟悉的一种叫作“马杜瓦”(即粮仓)的构筑物,重新为之赋予现代主义形式。灵活的矩形大空间与节制的服务空间塑造了一种与众不同的乡土建筑,由先锋建筑师将传统院落式住宅重新引入到城市环境中。这位业主比大多数城市精英更为亲近乡土建筑的源头,他对这些灵活空间的调整也都是自发而非强加的。建筑并未像周边的城市建筑那样占满地段,而是自在轻松地居于其中。

战争结束加速了商业化发展,这为建筑师创造了各种建筑类别的全新契机,但同样模糊了原创性的本土语言。今天,作为一个渴望达到中产收入水平的新兴经济体,斯里兰卡人选择的路径看起来仍是地域性的。例如,斯里兰卡人所熟悉的新加坡、马来西亚等国家,就提供了在商业开发和城市规划中适应气候环境的先例。拉夏吉里雅的贝弗利商业街(图5,见42页)是一座紧邻斯里兰卡议会大厦的湖畔购物中心,满足了大都市郊区消费者的野心和欲望。这个项目设计十分大胆,尤其是它忽略了过去几十年商业建筑的风格先例,并在类型学上选取了一种内向、封闭的模式。弱化消费驱动式的肤浅而转向场所营造是很困难的。戈德里奇·萨穆埃尔及其团队选择了触感凸显的材料,精心营造视线的关联,以雕琢这个与周边景观相互渗透的多层公共开放空间。他们舍弃了城市中其他那些西方风格的购物中心常见的合成感室内,而选择了更具质感的内表面材料。

像这样的城市建筑,延续了在内战期间涌现的坚固、隐蔽的类型学,以作为对外部危险的回应。垂直性、大体积的中庭和屋顶平台是建筑的标志性特征。尽管周围的建筑相对低矮,但这种防御性的内向化设计,亦有利于屏蔽那些可能会干扰到中产阶级消费者的交通、尘土和各种形式的社会侵扰。这样的设计选择是那个特定发展阶段在建筑形式上的表现。

拉夏吉里雅的帕林达·坎南加拉工作室(图6,见48页)是对粗野主义的一种精致诠释,直率地表达了这种封闭性的建筑形态。建筑冷峻的外表隔离出一个没有噪音和尘土的微环境。多层的混合功能独户住宅设置是城市区土地稀缺的结果,为此不得不将一块狭小地段上的体量最大化。这座建筑是面向未来的,因为它预见了一种密度提升的方式,不过如今周边的开放区域还是提供了花园和林地的借景。精心雕琢的清水混凝土表面以及其上的光影游戏带来视觉的愉悦。就像前面那个商业项目一样,形式的限制被强加在一种现代主义的抽象体量之上,不过这种形式其实来自斯里兰卡困顿的历史。

像这样的高端项目,以其精致的美学从郊区随性的商业增长与未经规划的开发项目中脱颖而出。然而就像其他亚洲城市一样,增长模式依靠的是不断堆积和对公共资源的侵蚀,建筑师也助长了这种碎片化的密度增长。在内战造成数十年的封闭性建造模式之后,斯里兰卡建筑师一直努力重塑社会介入性的设计。随着经济的赋权、增长的自信以及更多异文化美学的交互滋养,他们面临最大的挑战将是如何公平地分配这些机会。□

Ownership and self-expression of a distinct"Sri Lankan architecture" became possible during the mid to late 20th century when the first generation of foreign trained Sri Lankans returned to the island, and a school of architecture was created. The architecture of decolonisation took many forms, reflecting the tremendous social changes that followed independence from Britain in 1948. Government institutions and public monuments tended to respect the cultural hegemony of Buddhist aesthetics, a tendency which grew alongside archaeological discoveries of ancient historic cities and colonial and national affrmation of their cultural value. European modernism was introduced into the local context, largely in fl uenced by socialist pragmatism in the public arena and an aspiring urban middle class in private. China funded the first international conference hall to host the 1976 Non-Aligned nations' conference,its geometry influenced by Buddhist aesthetics.Pioneering architects combined modernist spaces with climate-sensitive designs.

The emergence of regionalism during the 1980s saw a marked shift in aesthetic orientation as institutional and domestic architecture was decolonised. Indigenous motifs drawn from vernacular architecture began to determine a Sri Lankan aesthetic and largely through the auspices of Aga Khan Program publications, local architects had their work published internationally. This was the heyday of regional decolonisation throughout South and Southeast Asia, with robust conversations on the role of architecture and the development of country-specific design ideologies.

We might periodise the architecture of Sri Lanka into 3 phases based on that legacy. The first period of decolonisation, described above, strengthened both national and cultural themes. The second period,following economic liberalisation in 1977, saw the creation of the new capital and parliament at Sri Jayewardenepura, displacing Colombo (the colonial capital) as the preferred administrative centre for the nation and opening up land for suburban development. Government- led urban rejuvenation and rural social housing became possible with injections of foreign aid. But within five years, the country was wracked by civil war which lasted from 1983 to 2009. Aesthetic talent was increasingly diverted towards hospitality architectures and a split occurred between these and urban commercial programmes. As a consequence of wartime insularity,design culture was increasingly diverted towards elite homes and the tourism industry, which occupied a greater representative space than other more socially sensitive programmes. Outside this tourism bubble, the violence and destitution of the war zone continued. Commercial developments persisted as agglomerations that filled out formerly low scale suburban areas.

Destruction in the war zone was mirrored by increasing fortification of urban dwellings and the multi storey apartments that rose to accommodate war-displaced refugees. Public spaces were barricaded and public life eroded by militancy and militarisation. This climate of ongoing catastrophe was compounded by the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami that devastated coastal villages and towns. The injection of international aid for Tsunami relief witnessed resurgence in socially oriented settlement projects.

The architects in this issue fall under the third phase in this periodisation with the ending of the civil war in 2009. A flurry of architectural activity followed. Reconstruction of the wardevastated north and east, and resettlement of the predominantly Tamil and Muslim, minority populations remains a major concern. Among these, Sumangala Jayatillaka's design for SOS International's Children's Village in Jaffna (Fig. 1,page 24) is a significant socially-oriented project.It continues a pattern of similar orphanages built in Sri Lanka and other impoverished or emerging economies by an international NGO, one that has developed a highly successful model for social service provision. Jayatillaka who has also built for SOS in other parts of the country, approaches each project with a view to continuing the local vernacular, as required by the INGO, so that the village may be seamlessly emplaced in its host context. In translating this desire into architecture,he has recreated a village setting, evocative of theagrarian settlements familiar to the children, still visible to them through the "natural (planted) fence"around the perimetre, although the houses are more robust than those around them. Given the high numbers of children orphaned at the end of the war,an empathetic architecture that ensures the safety of the family unit within a surrounding community recognises the need for social integration.

RAW, Robust Architecture Workshop, explores spatial continuity through the hospitality brief. A boutique hotel in the hill town of Kandy (Fig. 2, page 28) appears not as a stand-alone construction but as a natural, suppliant, extension of both city and hillscape. The complex accedes to its steep topography and scenic views of lake and mountain that orient it. Ignoring formal and material design constraints,the buildings twist and soar; their light- weight steel constructions akin to informal urban or industrial structures; integral to the acts of architecture that shape them. At times they clamber up the hill side or open to the street, disarmingly, in a manner reminiscent of the Kandy vernacular, but at no point do they bow to the formal geometries of colonial or cultural buildings. Milinda Pathiraja and his team have set aside the staid legacy of the picturesque that stultified hospitality architecture in the past.

Two projects by Hirante Welendawe, both in the commercial capital, Colombo, occupy tight urban sites.Nelung Arts Centre (Fig. 3, page 34), a teaching and performing arts facility, maintains the desire for social integration, described above, by inserting recreational and public gathering spaces in a congested urban area.The four storey building is designed in an L-shaped formation flanking these open areas with multilevel, vertical timber trusses shielding balconies that overlook them. The building form clearly expresses the forces needed to make room for public engagement;it is inspired by the way in which performances are traditionally staged in open air spaces, attracting a larger public audience, and designed to enable similar interactions in the city.

At Manel Nivasa (Fig. 4, page 38), the home of a self-made businessman rooted to his Sinhala-Buddhist and rural origins the same architect is inspired by Maduwa (paddy storage/barn)architecture, familiar to villagers, reworking them as modernist forms. The flexibility of these large rectangular volumes, and containment of few service spaces create a very different reading of vernacular architecture to the traditional courtyard structures reintroduced into the city by pioneering architects.The client is closer to those vernacular roots than most urban elites, and adjustment to these flexible spaces is not artificial. The building does not occupy the site perimetre like contiguous urban architecture but sits easily on the site.

The end of the war accelerated commercial development creating new opportunities for architects in every dimension of building, but it also blurred the clarity of that original indigenous script.Today, as an emergent economy, aspiring to middle income status, Sri Lanka's inspirations appear regional. Countries like Singapore and Malaysia to which Lankans have easy access offer acclimatised precedents for both commercial development and urban planning. "Beverley Street", in Rajagiriya(Fig. 5, page 42) a lakeside shopping complex in the vicinity of the Sri Lankan parliament caters to the growing ambitions and desires of cosmopolitan suburban consumers. The project is bold, given the neglect of aesthetic precedents for commercial architecture in the previous decades, and the inward orientation and consequent segregation of this building typology. Softening the superfluity of consumer driven agendas through place-making is difficult. Godridge Samuel and his team have used tactile materials and selective visual connections in crafting multiple public and open areas with fleeting views to the surrounding context. They have selected textured surfaces over the synthetic interiors typically found in Western style shopping complexes elsewhere in the city.

Urban architectures like these continue a fortified stealth typology that emerged during the civil war era as a response to external threats.Verticality, volumetric atriums, and roof terraces are its defining features. Despite the relatively low rise surrounds, a defensive inward orientation obviates traffic, dust and the forms of social intrusion that might disrupt middle income consumers. These design choices are symptomatic of a development stage manifest in architectural form.

Palinda Kannangara's studio dwelling in Rajagiriya (Fig. 6, page 48), a sensitive rendering of Brutalism, makes this pattern of fortification explicit. The building's unforgiving exterior preserves its micro climate from noise and dust.The multistorey, single unit, mixed use dwelling responds to land scarcity in urban areas and the need to maximise volumetric spaces on a small footprint. The building is futuristic as it anticipates densification, although at present adjacent open areas offer borrowed views into gardens and fields.Crafted rawfinishes and the play of light upon them are a source of visual delight. As in the commercial project above, formal constraints are artificially imposed in a version of modernist abstraction,but these forms have emerged out of Sri Lanka's troubled past.

High-end projects, such as these, with their exquisite aesthetics stand out against haphazard commercial growth and unplanned development in suburban areas. But as with Asian cities elsewhere,which grow by accretion, eroding public amenities,architects contribute to piecemeal densification.The struggle for Sri Lankan architects has been to design for social engagement following decades of defensive construction shaped by civil strife. With economic empowerment, rising self-confidence and greater aesthetic cross-fertilisation, delivering such opportunities equitably will prove to be the greatest challenge.□

5贝弗利商业街,拉夏吉里雅,斯里兰卡/Beverly Street,Rajagiriya, Sri Lanka(摄影/Photo: Eresh Weerasuriya)

6工作室住宅,拉夏吉里雅,斯里兰卡/Studio Dwelling,Rajagiriya, Sri Lanka(摄影/Photo: Sebastian Posingis)