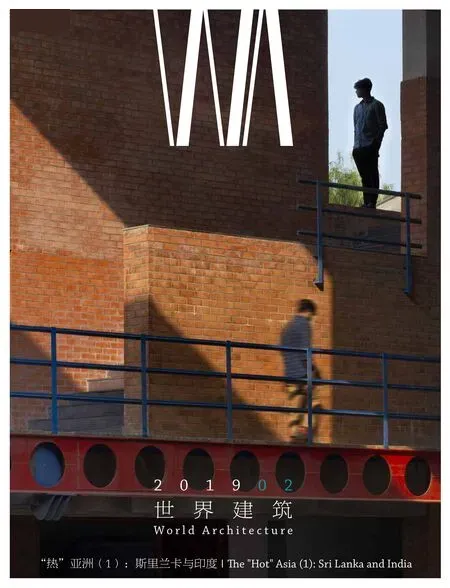

印度建筑

——多元化的关注点及诸多实践

A·斯里瓦桑/A.Srivathsan

天妮 译/Translated by TIAN Ni

从很多方面来说,2010年代对于印度建筑都是重要的10年。印度经济比以往任何时候都更加全球化、网络化并且活跃——增幅从2017年的6.7%增长到2019年的7.8%[1]——其影响是显而易见的。房地产业正在急速扩张,预计2028年的投资额将超过8500亿美元[2]。如果建筑院校的数量是反映建筑服务需求的一个指标,那么在过去70年中,该数值已经翻了100倍。印度在1929年仅有158名注册建筑师,如今,这一数量已经超过60,000人,且市场需求还在不断增长。然而,快速的城市化进程也带来了诸多挑战,如保障性住房短缺、环境压力、人口流动性问题、日益扩大的贫富差距、资源减少以及城市缺乏社会包容性等等。

当代境遇之下,多种多样的建筑实践应运而生,其中相当一部分是新生代建筑师完成的。在全部印度注册建筑师中,40岁以下的占70%以上[3]。不再被旧有观念约束,不再背负着自我施加的压力,建筑师们已经接受了当前挑战和机遇的新格局。或许印度建筑实践没有引发任何引人注目的先锋运动,也没有带来重大的理论转折,但它们同样具有思辨性、批判性和实用性。建筑师们已经意识到该行业的多元化需求及其所处环境的特殊性,并渴望通过创新途径作出回应。然而,一切并不尽如人意。挑战和阻碍比比皆是,例如亟需更多认同高设计品质的客户群,建筑设计的公共影响也需要再三重申。与创造性实践蕴含的可能性相比,意义深远的设计占比甚少。这些问题将留待后文讨论,先来谈谈多样性实践过程中的那些重大进程。

1 传承

自印度建筑学生协会在孟买成立以来,印度的现代建筑行业已有约100年历史了。这个由学生组成的小团体快速成长为印度建筑师学会——一个国家级的专业组织,旨在对该行业进行定义并构建该行业的宏观价值体系。英国建筑师克劳德·巴特利曾在孟买执业,并在印度第一所建筑学院任教。1942年他曾忧心忡忡地说,当时的首要挑战是建立起建筑这一行业,并通过制定严格的专业标准来保护其不受低劣和鼓吹的影响。建筑师的自我提升可经由3种途径完成:教育、司法体系及专业实践。事实证明,建筑师通过专业实践所取得的成就似乎比他们在其他两个领域所取得的成就具有更大意义和更大的影响力。

对于很多人来说,除了近年来的建筑实践以外,印度当代建筑可谓是乏善可陈。尽管种种迹象表明,许多评论都是以默认的分类方式——如现代派或后现代派——来描述印度建筑,并有结论认为,印度建筑实践在1980年代呈现出其自身特色之前都是拙劣的模仿。诸如此类的评论有失偏颇,正如谢尔登·帕洛克在思想文化史研究中敏锐指出的那样,评论者试图形成一种与西方建筑运动“在概念上的对偶”,而这种呼应其实并不存在[4]。

这并不是说大规模的国际建筑运动对印度建筑的实践没有影响。建筑师并不是被动的接受者,他们的反应也各不相同。正如克劳德·巴特利在其评论中总结的那样,印度建筑受到了“世界运动”的一定影响,但各种不同的气候条件和地方性需求也对这种形势有所调和[5]。本土的现代性、装饰艺术的杂糅、建筑实践、优质的资源和工匠们在同一时期出现并协同作用。在印度独立后的1950年代——也就是勒·柯布西耶和路易·康前来印度的时期——也出现了类似的发展轨迹。二人都为印度建筑带来了不可磨灭的影响,但紧随其后的并不是对他们遗留理念的盲目模仿。有的建筑师追随勒·柯布西耶和他的昌迪加尔规划,还有一些人,如查尔斯·柯里亚,则在甘地纪念馆等项目中探索着不同的风格体例;在德里,纳里·甘地创作了一系列对环境有所回应且令人回味的作品;约瑟夫·斯坦因在其建筑设计中将气候条件与景观精妙整合;北方有本杰明·波尔克和比诺伊·查特吉在加尔各答忙着用建筑干预解决区域性问题;南方有劳里·贝克潜心建造着具有社会意识的建筑——他以一己之力推动了一场运动,主张建造低成本且环境友好的住房。

近年来,特别是1990年经济自由化之后,印度的建筑实践百花齐放。近期,一场名为“建筑现状”的展览(由拉胡尔·迈赫罗特拉、卡万·梅塔和兰吉特·霍斯科特策展)清晰地表明,印度建筑弥漫着一种“合鸣之音”。 因此,为了更好地了解当前印度建筑发展所处的状态,较为明智的做法是摒弃默认的分类方式,转而透过一系列并置的建筑快照来勾勒全局。

2 剖析

孟买工作室的比乔伊·杰恩与萨姆普·帕多拉及合伙人事务所的萨姆普·帕多拉,他们都对现有工艺和建造技术有着同样的关注,这些都是方法多样性的例证。孟买工作室设计的恒河真木纺织工作室(图1,见52页),是喜玛拉雅山脚下一个根植于当地、居民和手工艺的小型纺织设计和生产车间。平面布局很简单,4个设置有存储、服务和工作区的L形转角空间围合成五边形的庭院。建筑外观是手工精心堆砌的,巧妙结合了当地盛产的传统材料,如砖、石、大理石和竹子。设计师的多次引导加之工匠们灵巧的手工艺让材料呈现出诗意之美。比乔伊·杰恩认为手工艺不仅仅是对材料的镶嵌,还关乎情感与沟通。对于材料和技术的运用他一向目的明确,美学的考虑渗透在他所有的决定之中。建造这样一个项目的过程是缓慢且谨慎的,例如,一个10m2的石灰混凝土屋顶花了5天时间才完成。

萨姆普·帕多拉也非常关注材料和建筑技术,但他不像杰恩那样在工艺理念的相关问题上那么一成不变。他以多种方式寻求切实的材料表达和材料利用率。他设计的祇园——一个位于马哈拉施特拉邦瓦里村的佛学中心——创造性地使用了玄武岩石粉和粉煤灰废料制成的夯土材料。他与昆纳什勒建筑技术与创新基金会合作(一个位于喀奇县致力于传统建筑技术服务的机构),以可再利用的木材和回收的粘土砖片为贫困人士提供住房和基础服务。另一方面,在沙尔达学校玛雅·索马亚图书馆 (图2,见58页)中,他选用了地中海的建筑技术——加泰罗尼亚砖拱系统。帕多拉在传统拱顶的基础上进行了创新,将苏黎世联邦理工学院建筑技术学院区块研究团队的研究和算法应用其中。基于这种便捷的算法,他设计出了舒展平滑的建筑形态和流动的室内阅读空间。屋顶是一个令人印象深刻的纤薄结构,由3层20mm厚的砖材组成,垂直铺设并用砂浆粘在一起。帕多拉对工艺理念呈开放态度,并根据场地、特殊情况和成本来选择适宜的技术。

另一个建筑师们非常关注的问题是如何让建筑设计根植于其所建造的场所中。许多人借由历史先例来解决这个问题,但并非总能成功。蒂洛森曾批判性地指出,有些设计师已经退而求其次,选择了仿制和令人失望的技巧拼凑[6]。对真实性的渴望应优先于对创造性解决方案的追求。而最近,一些建筑师开始更深入地关注这个问题,并提出了细致入微的解决方案。

浦那建筑师吉里什·多西,他以人们所熟知的借鉴历史先例的方式解决问题,但他很谨慎,不允许自己的作品以失真的象征性符号告终。其设计风格让人想起印度教的寺庙和马哈拉施特拉邦的传统房屋“瓦达斯”,但他并不主张追求真实感的再现。吉里什将自己的实践称为“传统的当代性”,并试图在历史对策和现代风格体例之间建立对话。在他近期项目浦那砖砌建筑学校(图3,见64页)中,多西运用了围绕轴线展开的对称布局以塑造空间的层次感,这种手法在印度寺庙中比较常见。他甚至直接借鉴了“哥普拉斯”(一种有华丽装饰的神庙大门)和金字塔的形制,但他选择的又是当代的建筑材料和结构,功能排布十分务实。他倾向于使用纯粹的形式和真材实料来赋予空间灵活性。他颠覆了传统的观念,这种运用裸露砖块和粗糙混凝土的风格在多西求学的昌迪加尔和艾哈迈达巴德比较常见。

1恒河真木纺织工作室,北阿坎德邦,印度/Ganga Maki Textile Studio, Uttarakhand, India(摄影/Photo: Studio Mumbai Architects)

2沙尔达学校玛雅·索马亚图书馆,戈伯尔冈,马哈拉施特拉邦,印度/Maya Somaiya Library, Sharda School, Kopergaon,Maharashtra, India(摄影/Photo: Edmund Sumner)

3砖砌建筑学校,浦那,马哈拉施特拉邦,印度/Brick School of Architecture, Pune, Maharashtra, India(摄影/Photo:Hemant Patil)

4CARE 集团,蒂鲁吉拉伯利,泰米尔纳德邦,印度/The CARE Group of Institutions, Tiruchirappalli, Tamil Nadu,India(图片来源/Source: Sanjay Mohe/Mindspace)

5印度管理学院教学综合体,班加罗尔,卡纳塔克邦,印度/Class Room Complex, Indian Institute of Management,Bengaluru, Karnataka, India(摄影/Photo: PHX India)

6国际管理学院,布巴内斯瓦尔,奥里萨邦,印度/International Management, Bhubaneswar, Orissa, India(摄影/Photo: Pradip Sen)

另一方面,来自班加罗尔的建筑师桑杰·摩诃和加尔各答建筑师阿宾·钱瑞的实践呈现出了不同的建筑情境。他们在借鉴历史先例的同时也关注着区域气候条件。摩诃常以富有表现力的庭院、便于交流的体系以及水体等元素来创造空间层次和局部联系。同样重要的是,这些特性也作为热带高效能的调节装置发挥着作用,创造了人们可以聚集在一起轻松交谈的公共空间。他设计的蒂鲁吉拉伯利CARE集团项目(图4)与班加罗尔印度管理学院教学综合体(图5)清楚地呈现了他的理念。阿宾·钱瑞也用到了类似的“调节装置”,但他有自己的建筑语言。例如,在布巴内斯瓦尔国际管理学院项目(图6)中,他用铁矾土这种当地材料和庭院、水体等设计元素将建筑与场所联系在了一起。这些装置调节了场地的微气候,遮挡了眩光,减少了热增量。对环境问题的考虑已然成为当务之急,同时,建筑表达也不再像前文案例那样受到限制,而是更具标志性且建筑规模更加宏大。

另一方面,居住在喀拉拉邦特里苏尔的年轻建筑师利乔·乔斯和雷利·利乔在面对类似问题时则较为激进。他们对建筑语境的定义不依赖曾经的理念,而是基于当下所面临的问题。通过借鉴先例来处理问题不一定是最适宜的方式。例如,喀拉拉邦以木建筑、铁矾土建筑和坡屋顶而闻名,而利乔和雷利却并没有运用这些形制。对他们来说,地域问题更为重要。喀拉拉邦正面临沙土、铁矾土严重稀缺的问题,木材也越来越珍贵。这种情况下,如仍在设计中沿用一直以来的形制和传统材料,环境问题并不会得到改善。因此,他们大胆地在苍翠的景观中置入了混凝土拱顶结构和呼吸式幕墙(图7)。对环境危机的应对和效能使该建筑在场所中有了立足之地,没有仅停留在对符号或形制的表面运用。

持有同样理念的还有什姆尔·贾瓦里·卡德里的作品,注意力集中于对文化和气候环境的适应。在该事务所的许多高端项目中——如位于蒂鲁帕蒂的马拉萨萨罗瓦酒店(图8,见70页)——她们虽然选用了传统的寺庙,却对其形制进行了深远地重新诠释,并没有过多沿用历史风格。对于借鉴历史先例的探讨暂且停留在概念形制层面,紧随其后的是审慎地选择关乎气候和功能的当代建筑材料。SJK建筑事务所对材料的运用与杰恩或帕多拉迥然不同,既没有刻意考虑成本,也不为提升趣味性,但却高度唯美和奢华。此外,她们倾向于以折衷的策略解决问题。

值得一提的是,印度当代的建筑实践并不仅仅关注工艺和场所营造,许多主流设计师也在对城市环境作出回应,为城市化问题寻求上乘的解决方案是关注点之一。来自金奈的建筑师团队architectureRed设计了一系列令人印象深刻的高层建筑,如金奈新月大学的教学楼(图9-11)。他们创造性地将楼板层叠、精心打造门窗、围合出室内庭院、提供宽敞的聚会空间并引入良好的照明系统。拉胡尔·迈赫罗特拉在海得拉巴为KMC公司总部大楼(图12,见76页)所做的设计则更胜一筹。在垂直的办公楼建筑结构普遍比较单调的时期,该建筑因种种原因脱颖而出。它通过设置双层表皮的立面,有效解决了气候和社会问题,使其他许多高层建筑望尘莫及。它的内表皮由混凝土框架和标准铝合金窗组成,外表皮则是可种植各种植物、附带有水培托盘的铝合金网状结构。灌溉系统与智能表皮合二为一,需要浇灌时可以适量放水。该体系不仅浇灌了植物,还能为建筑内部的空气加湿,这正是海得拉巴炎热气候条件下亟需的解决方案。园艺维护人员则可以穿行在双层表皮之间的空隙进行维护。迈赫罗特拉高度评价这种做法并认为这将有助于“提供一个社会界面,软化印度一种典型的企业组织中由阶级差异造成的常见的等级划分”。

对很多建筑师来说,其建筑实践以商业和居住类的项目居多,但也有少数设计师致力于解决一些日常问题,为城市和居民带来改变。古吉特·辛格·马塔鲁在苏拉特设计的阿什温尼库玛火葬场(图13,见80页)即是如此。1994年,以钻石贸易和纺织工业闻名的苏拉特爆发了严重的瘟疫,居民的死亡和疫情给政府和社区敲响了警钟,继而开始大力整治该市的公共卫生。疫情发生后,一家私人信托机构决定采用更清洁、更高效的方式来火化死者,并采纳了马塔鲁的设计方案,修建一个专供火化和哀悼的肃穆之地。火葬场在2000年开始动工,除了空间的功能性,用空间来承载情感也是该设计的可取之处。空间的组织逻辑结合了哀悼者及举办殡葬相关仪式的共同需求。看似冰冷的混凝土表皮包覆着主体,却把内部进行了恰当的分区。入口走廊通向一个可以放置焚化炉和柴堆的宽敞空间,哀悼者可以在焚化炉前的庭院聚集、静坐或唱祈祷歌。该场所向所有人免费开放,人们会互相提供力所能及的帮助。

另一个关注社会问题和环境条件的创新项目是象村(图14,见86页)。这个由拉胡尔·迈赫罗特拉设计的居住与旅游目的地位于斋浦尔的阿米尔堡山麓,约100头大象和驯象人常住于此。该项目对那些服务于旅游活动却在没有使用价值后便无人看管的大象进行了照料。大力支持该项目的州政府选择了迈赫罗特拉的设计,他为大象庇护所和驯象人居所设计了建筑组团。住宅单元和庇护所围合出一个共享空间,每个庇护所虽然只有18.5m2,却并没有被设计成局促的小空间。相反地,还有很多宽敞的户外空间,为加建留有余地。正在为旅游业服务或处于康复期的大象都可以受到照料。对景观的关注是另一个设计亮点。景观设计师穆哈·拉奥提出了一系列关于雨水收集和水循环的举措。自然界的水经由洼地、盆地、池塘和相连的蓄水池被收集起来。设计旨在尽可能地重建大象的栖息地,同时防止水土流失。

尽管非宗教领域的建筑造诣有很多亮点,但仍有不少宗教类的项目正在修建,印度建筑师们依然在努力为此寻求一种适宜的当代建筑语言。那些介于传统与现代性之间的实践危机四伏,似乎沿用已有的先例才是更为稳妥的做法。在此情境下,萨姆普·帕多拉在马哈拉施特拉邦设计的湿婆神庙(图15,见92页)具有重要的意义。有人将该项目视作创造力的原点。帕多拉认为印度传统的建筑形制将永远是设计语汇的基石——如室内圣域“咖巴格利哈”和外堂“曼达帕”—— 而建筑师的职责是将这些语汇融会贯通之后再创造性地用精准有力的方式呈现出来。该设计遵循了传统寺庙的空间逻辑,并将 “锡克哈拉” 式寺庙的装饰特征进行了简化。与典型的密闭式做法有所不同,该寺庙顶部微微开了一个小窗,以天光净化着内室。

3 挑战

印度当代的建筑实践当然也有不足之处。主要的建筑类型是私人委托、企业客户和部分国家级的项目。这里仅列举几个并不引以为傲的案例。拉胡尔·梅赫罗特拉、彼得·史克瑞沃和阿米特·斯里瓦斯塔瓦近日发表评论指出,目前的建筑实践只涉足了印度的极少数地区,“当代城市中有许多同质化的空间”还未被建筑实践潜在的新机遇所涵盖[7]。绝大多数的实践都发生在大都市,而发展中的二三线城市更需要优质且专业的建筑服务。此外,我们还面临着其他一些较为复杂的问题——如建筑师自身的局限性、没有赞助商以及缺乏追求高建筑品质的客户群——这些因素都导致了社会构筑物的品质良莠不齐。建筑实践一方面依赖于承建私人宅邸或委托机构给予的佣金是否充足,另一方面,社会住房的建造虽然是一项由国家支持的行为,却身陷在官僚体制的规章制度及未必富于远见的政策洪流之中。或许住房委员会还未意识到,建筑设计和建设是大幅提升经济适用房覆盖率的有效途径。就部分建筑师而言,他们也还没有尝试解决这些问题。

尽管可持续的建筑实践由来已久,但环境危机仍是一个尚未得到充分关注的问题,这方面还未取得长足的进展。最新情况仅限于LEED评价体系倡议的那些空泛举措。经济自由化带来了一系列未必节能环保的新材料,使这个问题愈发严重。虽然政府制定了能源法规和相关政策来解决这些问题,但并没有显著的变化。

安得拉邦的新首府阿马拉瓦蒂,是近年来最令人失望的建设项目之一。在昌迪加尔建成近60年后,人们自然对这个项目寄予了很大期望,它被视为新规划与新建筑理念最具潜力的试验田。问题的关键并不在于政府把项目委托给了一位外国建筑师,而是推进项目的方式不太可取。它为青年建筑师设置了不合常理的门槛,导致了操作层面不那么透明[8]。除了一些效果图,并没有公开过多的项目细节。阿马拉瓦蒂规划不仅没有像昌迪加尔那样让整个国家都充满朝气,甚至都没有在相关领域及业内人士当中产生涟漪。在当代创造性建筑实践正大步向前并谋求新机遇之时,诸如此类的项目着实会拖行业的后腿。

作为法律纲领的《建筑师法》,其修正草案也并不鼓舞人心。草案中的变革并不符合当前的经济形势,且仍是对过度管控的旧事重提。这些政策既不能提高建筑教育水平,也无法振兴建筑实践。

建筑从业者非常清楚,尽管存在诸多阻碍,但他们没有退路。这个过程中,乐观、希望与未知、疑虑并存。或许印度当代建筑实践唯一可能的发展方式,就是构建该行业的宏观价值体系。正如尤哈尼·帕拉斯马所言,兴建具有“更深远意义和从更深层面解决问题”的项目才应是建筑师的心之所向。□

In many ways, the current decade is a momentous one for Indian architecture. The Indian economy is globally networked and buoyant than ever before, growing from 6.7% (2017) to 7.8%(2019)[1]and the impact of this is visible. The real estate sector is expanding and the investment is estimated to exceed 850 billion USD by 2028[2]. If the number of architecture colleges is any indicator of demand for architectural services, it has multiplied a hundred fold in the last 70 years. From a meagre 158 registered members in 1929, the number of registered architects has exceeded 60,000, and more are needed. However, the rapid rate of urbanisation has also brought forth challenges such as a shortage of affordable housing, environmental distress,mobility issues, increasing wealth gap, dwindling resources and a lack of social inclusiveness of cities.

An overwhelming variety of architectural practices have emerged in response to these contemporary conditions, and a sizeable number of them are young. More than 70% of the registered architects in the country are less than 40 years of age[3]. Unfettered and unburdened by old perceptions and self-imposed categories, architects have embraced the current landscape of challenges and opportunities. Indian practices may not have thrown up any seductive avant-garde movements or offered major theoretical turns, but they are no less speculative, critical and pragmatic. They are conscious of the multiple demands made on the profession and the specificities of the context in which they are building and aspire to respond through creative approaches. However, all is not well. Challenges and impediments abound as the number of meaningful practices compared to the possibilities created are disproportionately less.The constituency for good design has to widen, and the public consequence of architecture has to be repeatedly reiterated. However, these issues are to be discussed later; first the significant strides that have resulted in the diversity of practices.

1 Legacy

It is about 100 years since the modern architecture profession emerged in India with the establishment of the Architecture Student's Association in Bombay. This small group of graduates soon grew into Indian Institute of Architects, a national level professional organisation tasked with defining the profession and establishing its relevance. As Claude Batley, the English architect who practiced out of Bombay and taught at the first school of architecture in India, worriedly remarked in 1942, the primary challenge of the time was to establish the profession and protect it from quacks by setting strict professional standards. Architects worked on three tracks to develop themselves:education, legal framework, and profession.Upon reflection, it appears that what they have accomplished through professional practice is more significant and impactful than what they have achieved in the other two.

在台北迎接跨年,有很多民众涌上街头,看台北市政府前广场举办的免费的跨年演唱会;在101大楼周围的大街小巷穿梭逛夜景,品尝夜市香飘四溢的小吃;在街头看艺人的花式表演……这一切,都是为了等待101大楼的烟火秀和新年的到来。

For many, contemporary architecture in India before recent times is not a story worthy of telling.Despite compelling evidence, many narratives describe architecture in India through universal categories such as modern and postmodern and conclude that Indian architecture was a poor imitation until it came on its own in the 1980s. Such commentaries are problematic, as Sheldon Pollock would incisively point out in the case of intellectual history, since they try to force a "conceptual symmetry" with the western architectural movements which did not exist[4].

It is not that the larger international movements did not cast impact on Indian practices.However, architects were not passive receivers nor were their responses uniform. As Claude Batley summed up in his comments, architecture in India was influenced "by the world movement", but various climatic and local demands also tempered it[5]. Homegrown modernity, art deco hybrids and practices working with optimal resources and artisans were simultaneously present. A similar trajectory followed in the post-Independence period when Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn arrived in India.Both left an indelible impact, but what followed was not a blind imitation of ideas left behind. If some followed Chandigarh and Le Corbusier, a few others such as Charles Correa explored different idioms in projects such as the Gandhi Ashram. Nari Gandhi created evocative works with a new material sensibility while in Delhi, Joseph Stein carefully integrated climatic conditions and landscape in his buildings. While Chatterjee and Polk in Kolkata were looking at how to address regional issues, in the south, Laurie Baker was quietly building socially conscious architecture and single-handedly inspired a movement for affordable and environmentally sensible buildings.

A thousand more flowers have bloomed in recent times, particularly after the economic liberalisation in 1990. As a recent exhibition titled the State of Architecture (curated by Rahul Mehrotra, Kaiwan Mehta, and Ranjit Hoskote) clearly showed, Indian architecture is sufiused with a "polyphony of voices."Hence, to get a better picture of the current state, it would be wise to drop categorisations, and, instead,portray a panoramic view by placing a series of snapshots next to one another.

2 Perspectives

Bijoy Jain of Mumbai Studio and Sameep Padora of sP+a architects (Sameep Padora & Associates),both of whom share the same concern for living crafts and building techniques, are illustrative examples of the diversity of approaches. In Ganga Maki Textile Studio (by Studio Mumbai,fig. 1, page 52), a small textile design and production facility at the foothills of Himalayas is rooted in place, people and craft. The plan is a simple arrangement of four L-shaped rectangular boxes around a courtyard with storage, service, and workspaces buttressing them. The buildings are carefully handmade, and it sensitively combines traditional materials such as locally harvested bricks, stone and marble, and bamboo. The materials gained poetic quality in the considerate hands of the craftsmen while also being continuously guided by the designer. Bijoy Jain believes that craft is not just embedded in materials,but is also about sensibilities and communication.Jain's use of materials and techniques have a clear destination, and aesthetic consideration permeates all decisions. The process of building such a project is slow and requires care. For example, a 10m2lime concrete roof took about 5 days to complete.

Sameep Padora too pays careful attention tomaterials and building techniques, but he is not as fixed as Jain regarding the provenance of techniques.He seeks tangible expression and material effciency in multiple ways. In his project Jetvan, a Buddhist Centre in Wari village, Maharashtra, he innovatively used rammed earth made from basalt stone dust and fly ash waste. He also chose repurposed timber, and salvaged clay roof tiles, and collaborated with the Hunnarshala Foundation for Building Technology and Innovations, an institution based in Bhuj that supports traditional techniques. On the other hand,in Maya Somaiya Library (Fig. 2, page 58) built in Kopergaon, a village near Jetavan, he preferred the brick Catalan Vault, a Mediterranean construction technique. Padora innovated on the traditional vault using the research knowledge and computational methods developed by the Block Research Group at the Institute of Technology in Architecture at ETH Zürich. The improvised method allowed him to design a free-flowing form and a fluid space inside to house books and reading spaces. The roof was an impressive thin structure made of 3 layers of 20 mm brick tiles, laid perpendicular to each other and held together by mortar. Padora is open about the idea of the craft and chooses his techniques based on the site, contingencies and cost considerations.

One of the issues that architects are still obsessively concerned about is to invent ways to root their buildings in the places they build. Many resort to historical precedents to achieve this and not all have been successful. As Tillotson would critically point out, some have slipped and settled for pastiches and disappointing collages[6]. Anxiety for authenticity has often taken the better of the quest for creative solutions. However, in recent times, a few architects are beginning to understand the issue better and have proposed nuanced solutions.

Girish Doshi, an architect, based in Pune goes down the familiar route of excavating historical precedents, but he is careful not to end up with a cardboard of symbolic elements. His rhetoric evokes Hindu temples and wadas (traditional houses of Maharashtra) but stops short of making naïve claims of recreating authentic experiences. Girish who calls his practice "traditional contemporary"tries to set a dialogue between historical strategies and modern idioms. In his recent project, Brick School of Architecture in Pune (Fig. 3, page 64),Doshi evokes the spatial layering and symmetrical arrangement around an axis commonly found in Hindu temples. He even makes formal references to gopuras (temple gateways) and pyramidal profiles. However, his materials and constructional choices are contemporary, and the arrangement of programmes are pragmatic. He prefers pure forms and authentic use of materials and configures his spaces to provide flexibility. By choosing the worn look of exposed bricks and rough concrete, which is common in Chandigarh and Ahmedabad where he trained, he unsettles traditional references.

On the other hand, architects such as Sanjay Mohe based in Bangalore and Abin Chaudhuri based in Kolkata demonstrate different ways of contextualising buildings.As much as they look to historical precedents, they also pay attention to climatic considerations. Mohe's designs use expressive courtyards, communicative frames, and elements such as water bodies and levels to create spatial layering and local connection. Equally important, the features also work as effective tropical devices and create collective spaces where people effortlessly gather to converse. His design for the CARE Group of Institutions,Tiruchirappalli (Fig. 4) and Class Room Complex,Indian Institute of Management, Bengaluru (Fig. 5) are clear demonstrations of his approach. Abin Chaudhuri also similar devices, but his architectural language is different. For example, in his design for International Management, Bhubaneswar (Fig. 6) also uses local materials such as laterite, and elements such as courtyards and water bodies to anchor the building with the place. These devices modulate the microclimate, cut harsh light and reduce heat gain, which are beginning to become imperatives. However, the architecture expression is not restrained as in the earlier examples but more iconic of a monumental scale.

On the other hand, Lijo Jos and Reny Lijo(young architects based in Thrissur, Kerala) who also engage with similar questions, take a radical route.To them, addressing context through precedents is not necessarily the best approach. They define context not as historical ideas, but based on issues faced. For example, Kerala is known for wood and laterite buildings and pitched roofs. However, Lijo and Reny's buildings do not make any reference to them. To both, issues of the place matter more.Kerala faces a severe shortage of sand and scarce laterite, and wood is getting precious. In such a situation, designing using historical references and traditional materials is unhelpful. They have boldly inserted concrete vaulted structures and breathing wall buildings in the verdant landscape (Fig. 7).Thus, performance and response to contextual challenges anchors the building to the place more than symbolic or formal references.

Placed in this continuum is the work of Shimul Javeri who is keen on accommodating culture and climate. In many of the firm's high-end projects such as the Marasa Sarovar Premiere (Fig. 8, page 70) in Tirupati, they chose traditional idioms, a temple in this case, and vastly reinterpret them leaving a minimal trace of its source. References to historical precedents stop at the conceptual stage and what follows is a careful choice of contemporary materials related to climate and function. Their use of materials is vastly different from that of Jain or Padora. It is neither cost conscious nor playful, but highly aestheticised and sumptuous. Moreover, their strategies are eclectic.

It is important to also register that contemporary practice in India is not all about crafts and placemaking. A good number of them are in the mainstream and respond to urban conditions. One of their key concerns is to find elegant solutions to vertical living. architectureRed based in Chennai has created a set of impressive tall buildings such as the one in Crescent University, Chennai (Fig. 9-11). They have creatively stacked floors, sculpted forms, created inner courts, provided generous gathering spaces andmade ways for good light. Rahul Mehrotra's design for KMC Corporate Offce in Hyderabad (Fig. 12, page 76)pushes the envelope further. Against the backdrop of mundane vertical offce structures, this building stands out for various reasons. It addresses the climatic and social concerns that daunt many tall buildings by putting in place a double skinned façade. While the inner skin is made of a concrete frame and standard aluminum windows, the outer one is of the aluminum trellis with hydroponic trays used for growing a variety of plants. The exterior façade works intelligently, and the misting system integrated with it releases water in a suitable amount if required. It not only takes care of the plants but also humidifies the air that enters the building inside, a much-needed solution for the hot climate of Hyderabad. The space between the two skins allows for the gardeners to walk and mend the pants. Mehrotra values such gestures and sees them as attempts to "provide a social interface that softens the common hierarchical divisions created by class differences in a typical corporate organisation in India."

7墙与拱的住宅,坎吉拉帕里,喀拉拉邦,印度/The Walls and Vaults House, Kanjirappally, Kerala, India(摄影/Photo:Praveen Mohandas)

8马拉萨萨罗瓦酒店,蒂鲁帕蒂,安得拉邦,印度/Marasa Sarovar Premiere, Tirupati, Andhra Pradesh, India(摄影/Photo: Rajesh Vora)

9.10新月大学航空学院,金奈,泰米尔纳德邦,印度/Department of Aeronautics, Crescent University, Chennai,Tamil Nadu, India

11新月大学生命科学院,金奈,泰米尔纳德邦,印度/School of Life Sciences, Crescent University, Chennai, Tamil Nadu,India(9-11图片来源/Sources: architectureRed)

For many, commercial and residential buildings are the mainstay of their practice, but a few have also tried to engage with everyday problems to make a difference in the city and for its people.Ashwinikumar Crematorium in Surat (Fig. 13, page 80) designed by Gurjit Singh Matharoo is clear a demonstration of this intention. In 1994, Surat, a city known for diamond trade and textile industry was severely affected by the plague. The deaths and trials that followed galvanised the state and communities to improve public health in the city.A private trust, following the disaster, decided to adopt cleaner and efficient ways to cremate the dead and chose the proposal by Matharoo, which created a dignified place to cremate and mourn. The crematorium is in operation since 2000. The success of this design is not only in its functionality but also in the manner in which it escapes the burdens of representation. It weaves spaces with needs of the mourners and the rituals associated with death. A grim concrete skin wraps the building and comfortingly isolates the areas within. The entrance corridor leads to an ample space that shelters the furnaces and the burning pyres. The garden in front of the furnaces allows the mourners to gather collect and sit in silence or sing bhajans (devotional songs).The whole facility is free and open to anyone who wishes to use it. People offer what they can or what they desire.

Another innovative project that is socially and environmentally conscientious is Hathi Gaon or Elephant Village (Fig. 14, page 86). Located at the foothills of Amer Fort, Jaipur, this residential enclave and tourist destination designed by Rahul Mehrotra houses 100 elephants and their mahouts.It takes care of elephants which are often exploited for tourist activities and left uncared after the purpose is served. Mehrotra's design, which was chosen by the State government that supported the project, created elephant shelters and mahout housing in the form of clusters. Dwelling units and elephant pavilions are organised around shared spaces. Shelters though small, about 18.5m2, are not built as timid boxes. Instead, they have generous outdoor areas and allows for incremental addition.The upgraded facility accommodates elephants in active use and also those convalescing. An equally important aspect of the design is the care bestowed on the landscape. Mohan Rao, the landscape architect who collaborated in this project, proposed a series of steps to harvest rainwater and recycled water. Through a series of swales, retention basins,ponds and interlinked reservoirs, water were collected. The planting strategy tried to recreate an elephant habitat as far as possible, while also preventing soil erosion.

While a lot could be said about the accomplishments in the non-religious realm, Indian architects are still grappling tofind a contemporary language for the religious places that are still built in large numbers. Practices are perilously torn between tradition and modernity, and often gravitate towards historical modes of designing. It is in this context that the Wadeshwar Temple in Maharashtra(Fig. 15, page 92) designed by Sameep Padora assumes significance. To some, this marks a creative beginning. Padora thinks that tradition will always remain as the beginning and will provide design elements such as garabhagriha (sanctum)and mandapas (pillared pavilions). The task of the architect is then to articulate and juxtapose them inventively. The design dispenses with the traditional sequential spatial configuration and strips off ornamentation on the Shikara (tower over the sanctum). Unlike a typical temple tower which is sealed at the top, here it is gently opened to allow light to wash the inner sanctum.

Another impressive turn in this context is re-imagination of sacred places as the extension of social spaces. Sai Mandir (Fig. 16,17), a Hindu temple in Venncahed, a village in Andhra Pradesh by Hari Krishna and his firm Studio for Environment and Architecture, based in Hyderabad, is an illustrative example of refreshing thinking. At one level, the design tries to rethink the architectural language of a temple by abstracting the historical form and using new construction techniques. At the other level, through intelligent design moves,the inner sacred spaces connect and extend to the adjacent public place. The inside permeates toembrace the sizeable 100-year-old neem tree outside and shares its shade. The sound and light from the inside enliven the outside in the evening. The temple interior draws the villagers to worship and rest,while its exterior with raised and extended plinth affords a place for the community to gather, chat,and at a time for business.

12KMC公司办公楼,海得拉巴,安得拉邦,印度/KMC Corporate Offce, Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh, India(摄影/Photo: Tina Nandi)

13阿什温尼库玛火葬场,苏拉特,古吉拉特邦,印度/Ashwinikumar Crematorium, Surat, Gujarat, India(摄影/Photo: Matharoo Associates)

14象村,斋浦尔,拉贾斯坦邦,印度/The Elephant Village,Jaipur, Rajasthan, India(摄影/Photo: Rajesh Vora)

15湿婆神庙,瓦德什瓦尔,马哈拉施特拉邦,印度/Shiva Temple, Wadeshwar, Maharashtra, India(摄影/Photo:Edmund Sumner)

3 Challenges

Contemporary architecture in India also has its equal share of fallacies and flaws. It mostly services private interests, corporate clients, and a few state projects. There are several ignominious examples and indulgences. Further, recent commentaries by Rahul Mehrotra, Peter Scriver and Amit Srivastava have pointed out that practices have only touched a small percentage of the conditions in the country and"there are parallel places within the contemporary city", where the benefits of new opportunities have not reached[7]. Most of the practices are located in the metropolitan cities, while better professional services are more needed in the growing tier two and three cities. There are also other compounding issues such as the limitations of the architects, and the narrow patronage and limited constituency that demands good design. The absence of well-designed social housing is an example of this condition.On one level, practices are mostly engaged with commissions for private homes and institutions.On the other level, social housing which remains a state-sponsored activity is caught in the bureaucracy of protocols and standards, and myopic policies.The housing boards are yet to realise that design and construction could substantially improve the affordable housing conditions. Architects for their part are yet to take this up the issue.

Environmental issues are another concern that are yet to be adequately addressed, despite a rich history of sustainable practices. Impressive strides have not been made in this realm. Recent interest has been limited to LEED ratings and other superficial responses. The problem is exacerbated with economic liberalisation that has brought with it a new bag of materials which are not necessarily energy efficient. Though energy codes and policies are in place to address these issues, change is not yet visible.

One of the most disappointing developments in recent times is the making of Amaravati, a new capital city in And hra Pradesh. Coming as it does, almost 60 years after Chandigarh, hopes were pinned on this project. It was seen as a potential test bed for new planning ideas and architecture. The issue is not that the state government awarded the project to a foreign architect, but the whimsical manner in which the entire project was conducted. It placed steep entry barriers for young practices and led the exercises less transparently[8]. Barring a few seductive images,not many details of the projects are available in the public domain. Unlike Chandigarh that animated the whole county, Amaravati has not created even a ripple amidst the professionals and institutions. When creative practices today are moving forward and looking for opportunities, projects such as this pulls the profession backwards.

The proposed amendments to the Architects Act, which provides the legal frameworks, have also not been encouraging. Proposed changes are not in keeping with the current economic landscape and still harp on excessive controls. This neither improves education nor enables practices to fl ourish.

Architectural practices know well that despite impediments, they have to go forward. There is optimism and hope as much as there is skepticism.The only possible way to move ahead is to establish the relevance of the profession by striving, as Juhani Pallasamaa would encourage, to build structures that have "deeper significance and purpose". □

16.17圣曼地亚寺庙,维纳赫德,安得拉邦,印度/Sai Mandir, Venncahed, Andhra Pradesh, India(摄影/Photos: Ujjwal Sannala)