脂多糖对甲状腺上皮细胞增殖、吞噬及胞内活性氧产生的影响

罗旋, 牟笑, 郑婷婷, 董昕, 刘宝翠, 毛朝明

(江苏大学附属医院核医学科, 江苏 镇江 212001)

桥本甲状腺炎是一种常见的器官特异性自身免疫性疾病,主要特点是甲状腺特异性T淋巴细胞和其他免疫细胞大量浸润甲状腺组织,以及甲状腺上皮细胞(thyroid follicular cells, TFCs)的破坏,最终导致甲状腺功能减退[1]。近年来研究表明,该病的发生与遗传、吸烟、过量碘的摄入及感染等有密切的关系[2-6]。

脂多糖是革兰阴性细菌细胞壁的主要致病成分,可以诱发多种炎性反应。已有实验证明脂多糖可以破坏T、B淋巴细胞对鼠甲状腺免疫蛋白的耐受进而促进桥本甲状腺炎的发生[7-8],但是确切的机制尚不清楚。本研究分析脂多糖对TFCs的增殖、凋亡、吞噬及胞内活性氧产生的影响,探讨脂多糖在桥本甲状腺炎发病中的作用。

1 材料与方法

1.1 材料

TFCs系Nthy-ori 3-1细胞购于ECACC细胞中心。胎牛血清、RPMI-1640培养基(Gibco公司)。脂多糖(Sigma公司),荧光微球(nile red fluorescent FluoSpheres® beads)为BD公司产品,MTT(上海碧云天生物公司),AnnexinV Alexa Fluor 647/PI凋亡检测试剂盒(南京福麦斯生物公司)。

1.2 方法

1.2.1 细胞培养 Nthy-ori 3-1细胞用含10%胎牛血清的RPMI-1640培养基(含100 μg·L-1链霉素、100 IU·L-1青霉素),置于37 ℃、5% CO2的培养箱培养。

1.2.2 MTT法检测Nthy-ori 3-1细胞增殖活性 将处于对数生长期的Nthy-ori 3-1细胞以每孔3.5×103个接种于96孔板中,每组设5个复孔,每孔加入200 μL含10%胎牛血清的RPMI-1640培养基(含100 μg·L-1链霉素、100 IU·mL-1青霉素),置于5% CO2培养箱培养。第2天,浓度梯度组分别加入0、10、20、100、150 ng·mL-1的脂多糖处理Nthy-ori 3-1细胞48 h;时间梯度组加入100 ng·mL-1的脂多糖分别处理Nthy-ori 3-1细胞24 h和48 h。处理结束后,弃去上清液,每孔加入终浓度为0.5 mg·L-1的MTT培养基100 μL,置于5% CO2培养箱孵育4 h。弃去上清液,每孔加入100 μL DMSO振荡5~10 min,使结晶充分溶解。用酶联免疫分析仪(EXL800)测定490 nm波长各孔光密度(D)值。每组实验重复3次,计算细胞增殖率,细胞增殖率(%)=D实验组/D对照组×100%。

1.2.3 流式细胞术检测Nthy-ori 3-1细胞的凋亡 根据细胞增殖的实验结果,选择100 ng·mL-1的脂多糖处理Nthy-ori 3-1细胞48 h,无EDTA的胰酶消化收集细胞,250×g,离心5 min。用100 μL缓存液悬浮细胞,加入5 μL AnnexinV Alexa Fluor 647和10 μL 20 μg·mL-1的PI溶液,混匀室温避光孵育15 min。孵育结束后,加400 μL PBS混匀,流式细胞仪检测分析。

1.2.4 荧光微球摄入实验评估Nthy-ori 3-1细胞的吞噬功能 实验前1天将Nthy-ori 3-1细胞以5×105个/孔接种于6孔板中,每孔加入2 mL含0.5%胎牛血清的RPMI-1640培养基(含100 μg·L-1链霉素、100 IU·mL-1青霉素),再分别加入0、10、20、100 ng·mL-1脂多糖,随后将6孔板置于5% CO2培养箱培养12 h后,每孔加入荧光微球4 μL(终浓度为7.2×105个/mL),置于5% CO2培养箱孵育4 h后,PBS洗3遍,收集细胞,流式细胞仪检测荧光强度。

1.2.5 荧光探针DCFH-DA法检测Nthy-ori 3-1胞内活性氧的水平 将Nthy-ori 3-1细胞以5×105个/孔接种于6孔板中,每孔加入2 mL含10%胎牛血清的RPMI-1640培养基(含100 μg·L-1链霉素、100 IU·mL-1青霉素),将6孔板置于5%CO2培养箱培养过夜。第2天,分别加入0、10、20、100 ng·mL-1脂多糖,4 h后每孔加入终浓度为10 μmol·L-1的DCFH-DA无血清RPMI-1640培养基1 mL,37 ℃培养箱孵育20 min。用无血清RPMI-1640培养基洗涤细胞3次。收集细胞,立即用流式细胞仪检测。

1.3 统计学分析

2 结果

2.1 脂多糖促进Nthy-ori 3-1细胞的增殖

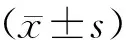

用0、10、20、100、150 ng·mL-1脂多糖分别作用Nthy-ori 3-1细胞48 h后,MTT检测结果显示,与0 ng·mL-1脂多糖对照组比较,各处理组Nthy-ori 3-1细胞的增殖率明显增加(F=11.43,P<0.01;图1A),在100 ng·mL-1脂多糖作用时增殖明显(t=5.115,P<0.01),且在0~100 ng·mL-1浓度范围内呈现一定的剂量依赖性。用100 ng·mL-1脂多糖分别作用Nthy-ori 3-1细胞24 h和48 h后,与对照组相比,细胞增殖明显(F=16.25,P<0.01;图1B),其中以48 h时尤甚(t=7.01,P<0.01)。

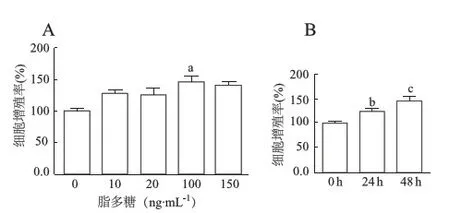

2.2 脂多糖对Nthy-ori 3-1细胞凋亡无明显影响

用100 ng·mL-1脂多糖作用Nthy-ori 3-1细胞48 h后,流式细胞术检测结果显示,与0 ng·mL-1脂多糖对照组比较,100 ng·mL-1脂多糖处理组细胞凋亡率降低,但差异无统计学意义(t=1.697,P>0.05;图2)。

A:脂多糖作用细胞48 h;B:100 ng/mL脂多糖处理细胞24 h和48 h;a:P<0.01,与0 ng/mL组比较;b:P<0.05,c:P<0.01,与0 h组比较

图1MTT法检测脂多糖处理后Nthy-ori3-1细胞的增殖率

图2 流式细胞术检测脂多糖对Nthy-ori 3-1细胞凋亡的影响

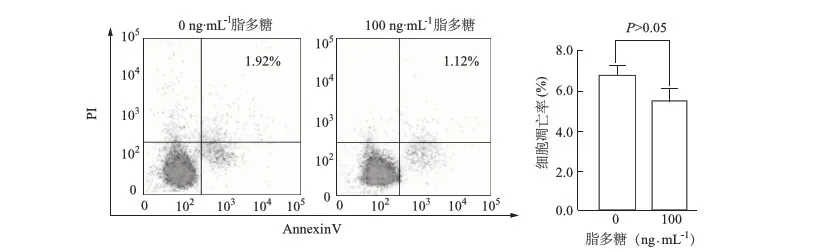

2.3 脂多糖促进Nthy-ori 3-1细胞的吞噬功能

荧光微球摄入实验结果表明,用0、10、20、100 ng·mL-1脂多糖分别作用12 h后,Nthy-ori 3-1细胞的吞噬率明显高于0 ng·mL-1脂多糖对照组(F=10.21,P<0.01;图3),在脂多糖20 ng·mL-1时达到最高峰(t=29.44,P<0.01),提示脂多糖能促进Nthy-ori 3-1细胞的吞噬且呈一定的剂量依赖性。

a:P<0.01,b:P<0.05,与0 ng·mL-1脂多糖比较

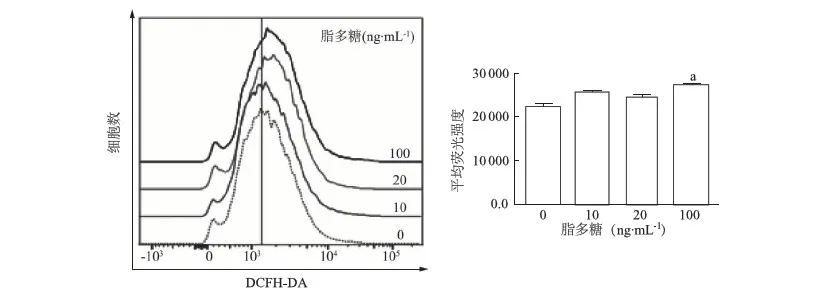

2.4 脂多糖促进Nthy-ori 3-1细胞活性氧的产生

用活性氧检测探针DCFH-DA的平均荧光强度(MFI)反映Nthy-ori 3-1胞内活性氧的水平。结果如图4所示,10、20、100 ng·mL-1脂多糖作用4 h后,Nthy-ori 3-1细胞胞内活性氧水平明显高于0 ng·mL-1脂多糖对照组(F=21.67,P<0.01),其中以100 ng·mL-1脂多糖时最为明显(t=10.65,P<0.01),显示胞内活性氧水平明显上升。

a:P<0.01,与0 ng·mL-1脂多糖比较

3 讨论

桥本甲状腺炎是一种多因素诱导的自身免疫紊乱性疾病,机体针对自身抗原发生免疫应答,大量的淋巴细胞浸润甲状腺组织,导致甲状腺功能受损,甲状腺肿大、纤维化最终导致甲状腺功能减退[9-10]。TFCs是构成甲状腺组织的主要细胞,感染和过量碘的摄入可以诱导TFCs表达MHCⅡ,使其变成抗原提呈细胞,促进桥本甲状腺炎的发生发展[11-12]。研究表明脂多糖可以促进naïve CD4+T细胞向针对甲状腺抗原的特异性Th17细胞分化,导致TFCs的免疫损伤,从而参与桥本甲状腺炎的发病过程[13-14]。本研究通过体外实验研究脂多糖对TFCs的增殖、吞噬和胞内活性氧产生能力的影响,探讨脂多糖在桥本甲状腺炎发病过程中的作用。

细胞增殖在一定程度上是细胞分化为多种功能表型的前提和基础。在桥本甲状腺炎的发病过程中,TFCs增殖能力的变化与发病密切相关。我们的实验证明在100 ng·mL-1浓度范围内脂多糖能够促进TFCs的增殖,对TFCs的凋亡无显著影响。这与脂多糖对免疫细胞等的促凋亡作用是不一致的。已有报道[15],脂多糖可以活化肝癌细胞表面的TLR4受体信号通路,促进肝癌细胞的生存和增殖。出现两种相反结论的原因可能与不同的细胞类型和不同的脂多糖作用浓度等因素相关。

高等动物的吞噬细胞通过吞噬作用,摄取和消灭感染的细菌,病毒以及损伤、衰老的细胞,是机体免受外来感染的第一道防线[16-17]。脂多糖可以增强单核-巨噬细胞的吞噬能力[18-19],然而脂多糖对正常上皮细胞的吞噬功能的影响却少有研究。本研究用荧光微球摄入法结合流式细胞术评价脂多糖对TFCs吞噬功能的影响,结果表明脂多糖能够增强TFCs的吞噬功能,提示在炎症介质介导下TFCs参与了炎症局灶部位的炎症反应。然而脂多糖促进TFCs吞噬功能的机制尚需进一步探讨。

活性氧是超氧阴离子、过氧化氢、羟自由基、一氧化氮等一类具有很高生物活性的含氧化合物的总称,参与细胞的增殖、凋亡、免疫及抗微生物等过程[20-21]。大量研究表明脂多糖能诱导巨噬细胞及上皮细胞产生大量的活性氧等炎性介质,进而加重局部炎性反应[22]。我们的研究结果显示,100 ng/mL脂多糖作用4 h能明显提高TFCs胞内活性氧的水平,从而加剧细胞的自身损伤,有助于桥本甲状腺炎的炎症反应和疾病发展。

综上所述,脂多糖通过促进TFCs增殖、上调TFCs的吞噬活性和提高胞内活性氧水平从而促进桥本甲状腺炎的炎症反应过程,显示了脂多糖在桥本甲状腺炎发生、发展中的重要致病作用。

[ 1 ] Weetman AP. Autoimmune thyroid disease: propagation and progression[J]. Eur J Endocrinol, 2003, 148(1): 1-9.

[ 2 ] Carlé A, Bülow Pedersen I, Knudsen N, et al. Smoking cessation is followed by a sharp but transient rise in the incidence of overt autoimmune hypothyroidism-a population-based, case-control study[J]. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf), 2012, 77(5): 764-772.

[ 3 ] Luo Y, Kawashima A, Ishido Y, et al. Iodine excess as an environmental risk factor for autoimmune thyroid disease[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2014, 15(7): 12895-12912.

[ 4 ] McLeod DS, Caturegli P, Cooper DS, et al. Variation in rates of autoimmune thyroid disease by race/ethnicity in US military personnel[J]. JAMA, 2014, 311(15): 1563-1565.

[ 5 ] Xu C, Wu F, Mao C, et al. Excess iodine promotes apoptosis of thyroid follicular epithelial cells by inducing autophagy suppression and is associated with Hashimoto thyroiditis disease[J]. J Autoimmun, 2016, 75:50-57.

[ 6 ] Caselli E, Zatelli MC, Rizzo R, et al. Virologic and immunologic evidence supporting an association between HHV-6 and Hashimoto′s thyroiditis[J]. PLoS Pathog, 2012, 8(10): e1002951.

[ 7 ] Esquivel PS, Rose NR, Kong YC, et al. Induction of autoimmunity in good and poor responder mice with mouse thyroglobulin and lipopolysaccharide[J]. J Exp Med, 1977, 145(5): 1250-1263.

[ 8 ] Flynn JC, Meroueh C, Snower DP, et al. Depletion of CD4+CD25+regulatory T cells exacerbates sodium iodide-induced experimental autoimmune thyroiditis in human leucocyte antigen DR3 transgenic classⅡ-knock-out non-obese diabetic mice[J]. Clin Exp Immunol, 2007, 147(3): 547-554.

[ 9 ] Antonelli A, Ferrari SM, Corrado A, et al. Autoimmune thyroid disorders[J]. Autoimmun Rev, 2015, 14(2): 174-180.

[10] Stassi G, De Maria R. Autoimmune thyroid disease: new models of cell death in autoimmunity[J]. Nat Rev Immunol, 2002, 2(3): 195-204.

[11] Zheng T, Xu C, Mao C, et al. Increased interleukin-23 in Hashimoto′s thyroiditis disease induces autophagy suppression and reactive oxygen species accumulation[J]. Front Immunol, 2018, 9:96.

[12] Kostic I, Toffoletto B, Fontanini E, et al. Influence of iodide excess and interferon-γ on human primary thyroid cell proliferation, thyroglobulin secretion, and intracellular adhesion molecule-1 and human leukocyte antigen-DR expression[J]. Thyroid, 2009, 19(3): 283-329.

[13] Kristensen B, Hegedus L, Madsen HO, et al. Altered balance between self-reactive T helper (Th)17 cells and Th10 cells and between full-length forkhead box protein 3 (FoxP3) and FoxP3 splice variants in Hashimoto′s thyroiditis[J]. Clin Exp Immunol, 2015, 180(1): 58-69.

[14] McAleer JP,Liu B,Li Z,et al. Potent intestinal Th17 priming through peripheral lipopolysaccharide-based immunization[J]. J Leukoc Biol, 2010, 88(1): 21-31.

[15] Wang L, Zhu R, Huang Z, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced toll-like receptor 4 signaling in cancer cells promotes cell survival and proliferation in hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Dig Dis Sci, 2013, 58(8): 2223-2236.

[16] Thomas CA, Li Y, Kodama T, et al. Protection from lethal gram-positive infection by macrophage scavenger receptor-dependent phagocytosis[J]. J Exp Med, 2000, 191(1): 147-156.

[17] Bi WJ, Li DX, Xu YH, et al. Scavenger receptor B protects shrimp from bacteria by enhancing phagocytosis and regulating expression of antimicrobial peptides[J]. Dev Comp Immunol, 2015, 51(1): 10-21.

[18] Kobayashi Y, Inagawa H, Kohchi C, et al. Lipopolysaccharides derived from pantoea agglomerans can promote the phagocytic activity of amyloid β in mouse microglial cells[J]. Anticancer Res, 2017, 37(7): 3917-3920.

[19] Zhou J, Tai G, Liu H, et al. Activin A down-regulates the phagocytosis of lipopolysaccharide-activated mouse peritoneal macrophagesinvitroandinvivo[J]. Cell Immunol, 2009, 255(1/2): 69-75.

[20] Kiselyov K, Jennigs JJ Jr, Rbaibi Y, et al . Autophagy, mitochondria and cell death in lysosomal storage diseases[J]. Autophagy, 2007, 3(3): 259-262.

[21] Inoue M, Sato EF, Nishikawa M, et al. Mitochondrial generation of reactive oxygen species and its role in aerobic life[J]. Curr Med Chem, 2003, 10(23): 2495-2505.

[22] Fan J, Frey RS, Malik AB, et al. TLR4 signaling induces TLR2 expression in endothelial cells via neutrophil NADPH oxidase[J]. J Clin Invest, 2003, 112(8): 1234-1243.