中国郑州儿童炎症性肠病与欧洲、韩国儿童炎症性肠病对比分析

冯永星,李建生,李东颖

郑州大学第一附属医院消化内科,河南 郑州 450052

炎症性肠病(inflammatory bowel diseases,IBD)是一种特发性、慢性胃肠道炎症,包括克罗恩病(Crohn’s disease,CD)、溃疡性结肠炎(ulcerative colitis, UC)。欧美地区儿童IBD(pediatric-onset IBD, PIBD)发病率较高,因此,关于PIBD的相关报道,欧美地区远高于亚洲地区。PIBD发病率逐年上升,英国HENDERSON等[1]对PIBD长达40年的研究显示,PIBD的发病率逐年增高,尤其是CD患儿,16岁以下IBD的发病率从每年4.45/10万(1990-1995年)增长至每年7.82/10万(2003-2008年)。随着生活环境及饮食习惯改变,亚洲地区PIBD发病率逐渐升高,中国香港威尔斯亲王医院的队列研究[2]显示,1990-2001年CD和UC的发病率增长迅速,分别从0.4/10万、0.8/10万增长至1.0/10万、1.2/10万。本研究统计中国郑州地区PIBD发病情况,并分别与韩国[3]、欧洲(EUROKIDS)[4-5]PIBD性别、发病年龄、发病部位、病理改变及肛周病变进行对比分析,得出亚洲地区与欧洲地区PIBD发病特点,更科学地指导临床诊断与治疗。

1 资料与方法

1.1一般资料收集2011年5月至2016年10月就诊于郑州大学第一附属医院的年龄<18岁PIBD患者,根据蒙特利尔分类[6]对发病部位进行统计,由于LEVINE等[5]对于UC的研究方法根据巴黎分类进行发病部位分类,因此,为进行部位比较分析,将巴黎分类E2、E3与左侧UC进行比较,E4与弥漫性UC进行比较。剔除临床资料不全的患者,共收集21例CD、32例UC共53例IBD患者。

1.2方法统计分析患者性别、年龄、发病部位、病理改变、肛周病变等,并与欧洲及韩国相关研究进行对比分析。

1.3统计学分析采用SPSS 21.0对数据进行统计分析,采用χ2检验或Fisher精确检验对分类变量进行检验,P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果

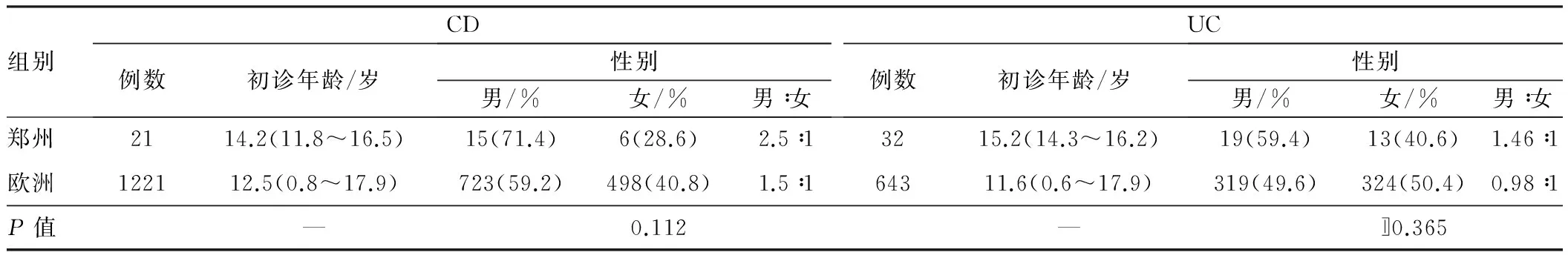

2.1与欧洲PIBD患者发病年龄及性别比例比较入选CD患者21例、UC患者32例。如表1所示,与欧洲CD、UC患者比较,中国郑州地区PIBD发病平均年龄较大(CD:14.2岁vs12.5岁;UC:15.2岁vs11.6岁),男女比例相比,差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。

表1 中国郑州地区与欧洲PIBD患者发病年龄及性别比例比较 Tab 1 Comparison of the age and sex ratio of PIBD patients in Zhengzhou of China and Europe

2.2与欧洲CD患者发病部位比较如表2所示,与欧洲PIBD对比分析,中国郑州地区CD患儿回肠末端发病率较高(38.1%vs16.3%,P=0.018),回结肠发病率较低(14.3%vs52.8%,P=0.001),并发或孤立上消化道疾病的患儿较低(14.3%vs46.2%,P=0.003)。病理表现中,中国郑州地区CD患儿并发肠道狭窄的发病率较高(33.3%vs13.2%,P=0.018),而欧洲患儿无狭窄、无浸润的病理表现较多见(61.9%vs82.0%,P=0.04),肛周病变相比,差异无统计学意义(P=0.690)。

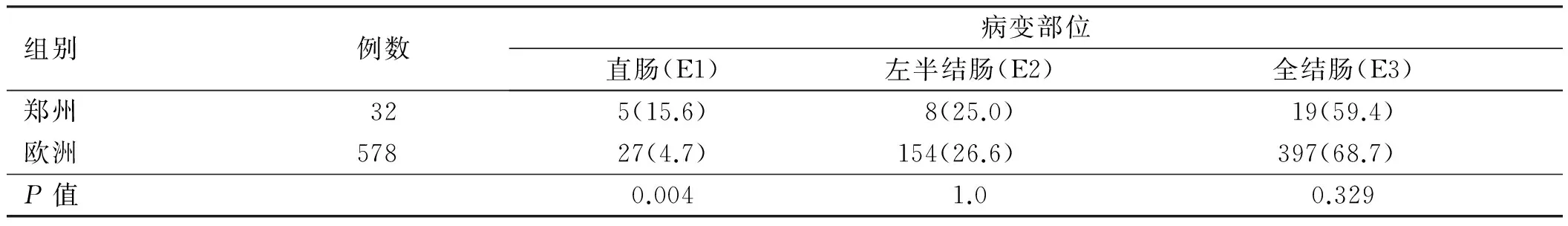

2.3与欧洲UC患者发病部位比较如表3所示,与欧洲UC患儿比较,中国郑州地区儿童直肠病变发病率较高(15.6%vs4.7%,P=0.004)。其余结肠病变部位差异未见明显统计学意义(P>0.05)。

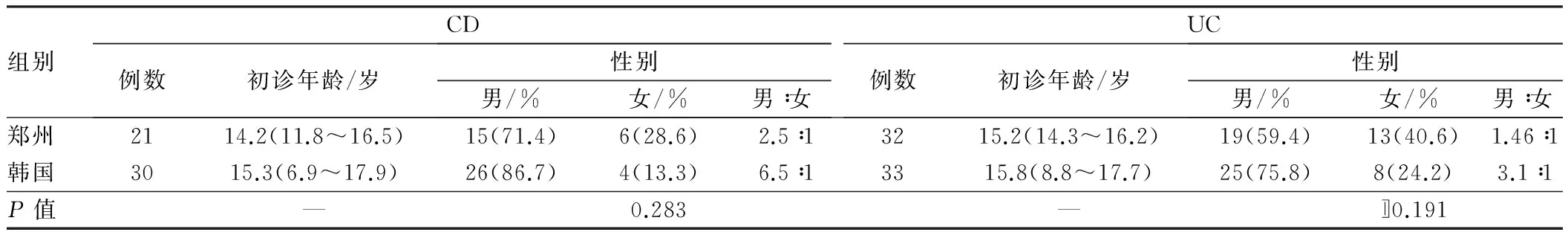

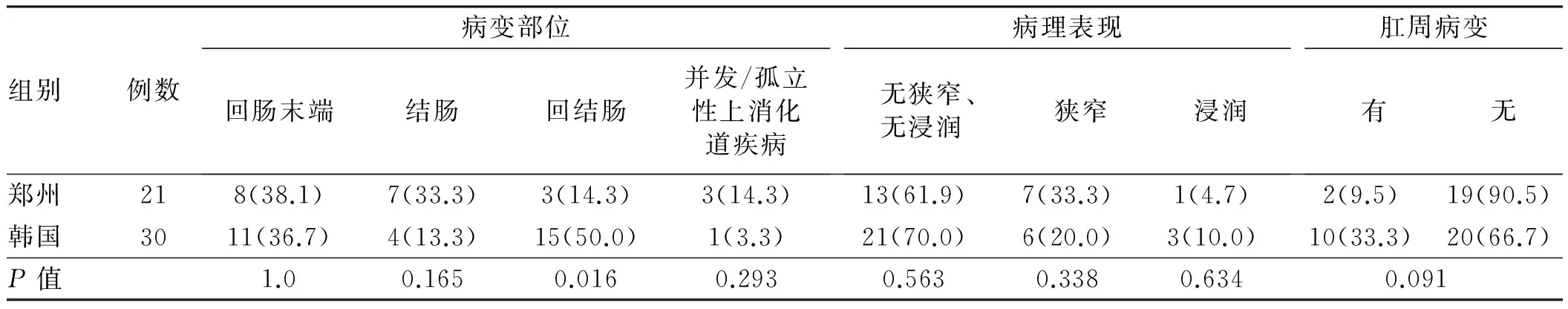

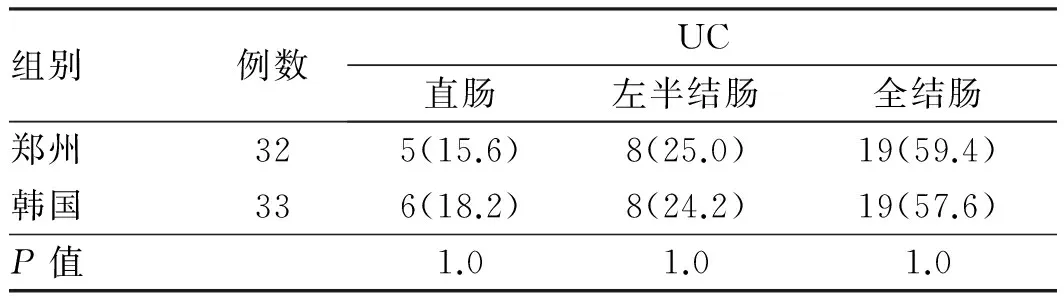

2.4与韩国PIBD患者一般资料比较如表4~6所示,与韩国PIBD相比,中国郑州地区PIBD发病年龄稍早(CD:14.2岁vs15.3岁;UC:15.2岁vs15.8岁),但相差不大;中国郑州地区PIBD回结肠发病率较低(14.3%vs50.0%,P=0.016),其余发病部位及病理改变相比,差异均无统计学意义(P>0.05)。

表2 中国郑州地区与欧洲儿童CD临床特点对比结果 Tab 2 Comparison of the characteristics of pediatric-onset CD patients in Zhengzhou of China and EUROKIDS by the montreal classification 比例/%

表3 中国郑州地区与欧洲儿童UC发病部位对比结果 Tab 3 Comparison of the characteristics of pediatric-onset UC patients in Zhengzhou of China and EUROKIDS by the montreal classification 比例/%

表4 中国郑州地区与韩国PIBD的分布特点对比结果 Tab 4 Patients demographics of PIBD in Zhengzhou of China and Korea

表5 中国郑州地区与韩国儿童CD的临床特点对比 Tab 5 Comparison of the characteristics of pediatric-onset CD patients in Zhengzhou of China and Korea by the montreal classification 比例/%

表6中国郑州地区与韩国儿童UC发病部位对比结果

Tab6Comparisonofthecharacteristicsofpediatric-onsetUCpatientsinZhengzhouofChinaandKoreabythemontreal

classification 比例/%

3 讨论

中国郑州与欧洲PIBD对比分析中,CD及UC男女发病比例差异未见统计学意义,其中CD表现出男性发病比例较高(男∶女=2.5∶1),该统计结果与之前相关研究结果一致,其中中国香港统计报道[2]指出,CD发病比例为男∶女=2.5∶1,同样,韩国相关报道指出,CD的发病比例为男∶女分别为6.5∶1[3]、2∶1[6]、2.2∶1[7],本文再次证实,在CD发病比例中男性占优势的现状,然而欧洲关于儿童CD相关报道并未见明显男女发病比例差异[8-10]。UC发病比例男女差异虽不如CD男女差异明显,但仍表现出男性发病占优势,男∶女=1.46∶1。欧洲地区与亚洲地区不同,欧洲PIBD发病比例为男∶女=1∶1[4],甚至有关研究表明欧洲地区UC女性发病比例占优势,VIND等[11]报道指出,IBD男女比例为1∶1.21。因此,结合上述研究结果,亚洲地区IBD男性发病比例较女性高,欧洲地区IBD男性发病比例未见明显优势,甚至欧洲某些地区女性发病比例较男性稍高。

关于近年来亚洲地区IBD发病率增加的原因,中国相关报道[12-13]指出,中国南部与北部IBD发病率不同,NG等[14]研究表明,亚洲IBD发病率增加原因可能与西式化的饮食方式、吸烟、城市化的社会环境、抗生素的应用及免疫状态有关。亚洲地区IBD男性发病比例较高,其原因可能是男性吸烟率较高及西方化饮食方式比例较高,其次,免疫、社会环境影响等均可能是亚洲地区与欧洲地区男女发病比例不同的原因[15]。PRIDEAUX 等[16]荟萃分析表明,基因、遗传异质性及环境在IBD的发病中起着至关重要的作用,该研究结果表明,英国移民的亚洲人群中,印度教徒与锡克教徒UC发病率高于欧洲种族,CD发病率等于或低于欧洲种族。出生在英国的南亚移民子女UC的病变范围与当地居民相似甚至病情比当地居民重。

对于IBD的发病年龄统计结果表明,中国郑州地区与韩国PIBD发病年龄均比欧洲PIBD偏大,中、韩PIBD发病年龄相仿。

CD发病部位统计结果表明,中、韩、欧儿童CD结肠L2发病率约占总数的1/3,差异无统计学意义。中国郑州地区、韩国儿童CD回肠末端L1发病比例均较欧洲儿童高,对比分析结果,差异有统计学意义,其次,韩国、欧洲儿童回结肠L3发病比例较高,约占总数的1/2。中国郑州地区儿童CD发病部位最常见为回肠末端L1,累及回结肠L3发病比例较低,刘爱琴等[17]研究结果也表明,年龄<17岁组CD回肠末端L1发病率较高,为50.0%,而回结肠L3发病部位发病率为0。韩国肠道病协会[18]关于成人CD长达20年的研究结果表明,CD发生于回结肠的发病比例有逐渐升高的趋势。多数关于成人CD发病部位的研究表明,亚洲地区成人CD发病部位主要为回结肠L3,中国广东相关报道[12]指出,CD发生于回结肠部位L3的发病比例约为70.6%,中国香港研究[19]结果表明,CD发生于回结肠L3部位的发病比例为50.5%。中国武汉[20]对于IBD的前瞻性研究结果表明,发生于回结肠L3的CD发病比例约为61%。然而西方国家[21-23]对于成人CD发病部位的研究结果表明,结肠发病率较高。因此,关于CD发病部位仍需更多的临床研究。中国郑州地区与韩国儿童CD并发或孤立上消化道疾病L4的发病率远低于欧洲儿童,中、韩儿童CD并发或存在孤立上消化道疾病L4的发病比例差异未见明显统计学意义,表明亚洲地区儿童CD存在上消化道疾病L4的发病率低于欧洲地区,本研究结果与中国广东ZENG等[12]研究结果相似,该研究结果表明,CD患者中孤立或并发上消化道疾病L4的发病比例为23.5%,然而韩国KIM等[24]研究表明,并发或孤立上消化道疾病L4的CD所占比例为44%,较本研究中亚洲地区CD L4发病比例高。因此,关于儿童及成人CD并发或孤立上消化道疾病L4的发病率仍需进一步大样本研究。

关于CD发病部位病理改变的研究,中国与韩国儿童CD病变部位狭窄(B2)发生率均较欧洲儿童高,中国与欧洲病变部位狭窄发生率对比分析结果为(33.3%vs13.2%,P=0.018),此研究结果与PRIDEAUX等[25]对香港与墨尔本的IBD对比分析研究结果一致,香港CD患者病变部位狭窄发生率较墨尔本CD患者病变部位狭窄发生率高(11.5%vs5.8%,P=0.003),表明亚洲地区儿童CD病变部位狭窄发生率较西方国家低。

中国郑州地区与欧洲儿童CD肛周病变发生率差异未见明显统计学意义,然而韩国儿童CD肛周病变发生率较高,LEE等[26]研究表明,16岁以下的CD患儿肛周病变发生率为31.3%,因此,关于儿童CD肛周病变仍需进一步临床研究。

UC发病部位的统计分析结果表明,中国郑州地区儿童UC直肠(E1)发病率远高于欧洲儿童(15.6%vs4.7%,P=0.004),中国郑州地区儿童UC发病部位与韩国儿童比较,差异未见明显统计学意义,该统计结果与KIM等[24]研究结果相似,其结果表明,儿童UC直肠发病率为21.0%,同样中国广东[12]关于IBD的研究结果表明,UC直肠炎发病率为35.5%,中、韩、欧研究结果均表明,PIBD发病率最高的部位为全结肠,英国VAN等[27]统计分析儿童与成人UC发病部位,研究结果表明,儿童及成人IBD发病最常见部位均为全结肠,且儿童CD全结肠炎发病率比成年人全结肠炎发病率高。

患有IBD的儿童中,炎症反应与低营养状态均会导致儿童生长速度降低,增加的细胞因子产物作用于肝脏表达的胰岛素样生长因子(IGF-1)与长骨的软骨板,且免疫功能紊乱导致的生长激素不敏感,是生长速度迟缓的主要机制[28],IBD严重影响儿童的生长速度及生活质量。本研究结果表明,东西方PIBD发病部位、病理学改变及临床特点不同,对于PIBD的治疗方案及预后的研究仍需进一步大样本研究。

[1] HENDERSON P, WILSON D C. The rising incidence of paediatric-onset inflammatory bowel disease [J]. Arch Dis Child, 2012, 97(7): 585-5866. DOI: 10.1136/archdischild-2012-302018.

[2] LEONG R W, LAU J Y, SUNG J J. The epidemiology and phenotype of Crohn’s disease in the Chinese population [J]. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2004, 10(5): 646-651. DOI: 10.1097/00054725-200409000-00022.

[3] LEE H A, SUK J Y, CHOI S Y, et al. Characteristics of Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Korea: Comparison with EUROKIDS Data [J]. Gut Liver, 2015, 9(6): 756-760. DOI: 10.5009/gnl14338.

[4] DE BIE C I, PAERREGAARD A, KOLACEK S, et al. Disease phenotype at diagnosis in pediatric Crohn's disease: 5-year analyses of the EUROKIDS registry [J]. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2013, 19(2): 378-85. DOI: 10.1002/ibd.23008.

[5] LEVINE A, DE BIE C I, TURNER D, et al. Atypical disease phenotypes in pediatric ulcerative colitis: 5-year analyses of the EUROKIDS Registry [J]. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2012, 6(2): 370-377. DOI: 10.1002/ibd.23013.

[6] KIM B J, SONG S M, KIM K M, et al. Characteristics and trends in the incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in Korean children: a single-center experience [J]. Dig Dis Sci, 2010, 55(7): 1989-1995. DOI: 10.1007/s10620-009-0963-5.

[7] LEE N Y, PARK J H. Clinical features and course of Crohn disease in children [J]. Religion in Communist Lands, 2008, 14(2):210-211.

[8] KUGATHASAN S, JUDD R H, HOFFMANN R G, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of children with newly diagnosed inflammatory bowel disease in Wisconsin: a statewide population-based study [J]. J Pediatr, 2003, 143(4): 525-531. DOI: 10.1067/S0022-3476(03)00444-X.

[9] OUYANG Q, TANDON R, GOH K L, et al. The emergence of inflammatory bowel disease in the Asian Pacific region [J]. Curr Opin Gastroenterol, 2005, 21(4): 408-413.

[10] LOFTUS E V, SCHOENFELD P, SANDBORN W J. The epidemiology and natural history of Crohn’s disease in population-based patient cohorts from North America: a systematic review [J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2002, 16(1): 51-60. DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01140.x.

[11] VIND I, RIIS L, JESS T, et al. Increasing incidences of inflammatory bowel disease and decreasing surgery rates in Copenhagen City and County, 2003-2005: a population-based study from the Danish Crohn colitis database [J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2006, 101(6): 1274-1282. DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01140.x.

[12] ZENG Z, ZHU Z, YANG Y, et al. Incidence and clinical characteristics of inflammatory bowel disease in a developed region of Guangdong Province, China: A prospective population-based study [J]. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2013, 28(7): 1148-53. DOI: 10.1111/jgh.12164.

[13] ZHAO J, NG S C, LEI Y, et al. First prospective, population-based inflammatory bowel disease incidence study in mainland of China: the emergence of “western” disease [J]. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2013, 19(9): 1839-1845. DOI: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e31828a6551.

[14] NG S C, BERNSTEIN C N, VATN M H, et al. Geographical variability and environmental risk factors in inflammatory bowel disease [J]. Gut, 2013, 62(4): 630-649. DOI: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303661.

[15] WANG Y F, ZHANG H, OUYANG Q. Clinical manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease: East and West differences [J]. J Dig Dis, 2007, 8(3): 121-127. DOI: 10.1111/j.1443-9573.2007.00296.x.

[16] PRIDEAUX L, KAMM M A, DE CRUZ P P, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease in Asia: a systematic review [J]. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2012, 25(8): 436-438. DOI: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2012.07150.x.

[17] 刘爱琴, 黄文字, 李倩倩, 等. 不同年龄炎症性肠病临床特征单中心分析[J]. 世界华人消化杂志, 2016, 24(4): 623-630. DOI: 10.11569/wcjd.v24.i4.623.

LIU A Q, HUANG W Z, LI Q Q, et al. Single center analysis of clinical characteristics about inflammatory bowel disease in different age groups [J]. World Chinese Journal of Digestology, 2016, 24(4): 623-630. DOI: 10.11569/wcjd.v24.i4.623.

[18] YANG S K, YUN S, KIM J H, et al. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in the Songpa-Kangdong district, Seoul, Korea, 1986-2005: a KASID study [J]. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2008, 14(4): 542-429. DOI: 10.1002/ibd.20310.

[19] CHOW D K, LEONG R W, LAI L H, et al. Changes in Crohn’s disease phenotype over time in the Chinese population: Validation of the Montreal classification system [J]. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2008, 14(4): 536-541. DOI: 10.1002/ibd.20335.

[20] ZHAO J, NG S C, BURISCH J, et al. First prospective, population-based inflammatory bowel disease incidence study in China-the emergence of “western” disease [J]. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2013, 19(9): 1839-1845. DOI:10.1016/S0016-5085(12)63075-3.

[21] SJÖBERG D, HOLMSTRÖM T, LARSSON M, et al. Incidence and clinical course of Crohn’s disease during the first year-Results from the IBD Cohort of the Uppsala Region (ICURE) of Sweden 2005-2009 [J]. J Crohn's Colitis, 2014, 8(3): 215-222. DOI: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.08.009.

[22] LAPIDUS A. Crohn’s disease in Stockholm County during 1990-201: An epidemiological update [J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2006, 12(1): 75-81.

[23] WOLTERS F L, RUSSEL M G, SIJBRANDIJ J, et al. Phenotype at diagnosis predicts recurrence rates in Crohn’s disease [J]. Gut, 2006, 55(8): 1124-1130. DOI: 10.1136/gut.2005.084061.

[24] KIM B J, SONG S M, KIM K M, et al. Characteristics and trends in the incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in Korean children: a single-center experience [J]. Dig Dis Sci, 2010, 55(7): 1989-1995. DOI: 10.1007/s10620-009-0963-5.

[25] PRIDEAUX L, KAMM M A, DE CRUZ P, et al. Comparison of clinical characteristics and management of inflammatory bowel disease in Hong Kong versus Melbourne [J]. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2012, 27(5): 919-927. DOI: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06984.x.

[26] LEE E J, KIM T O, SONG G A, et al. Clinical features of Crohn’s disease in Korean patients residing in Busan and Gyeongnam [J]. Intest Res, 2016, 14(1): 30-36. DOI: 10.5217/ir.2016.14.1.30.

[27] VAN L J, RUSSELL R K, DRUMMOND H E, et al. Definition of phenotypic characteristics of childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease [J]. Gastroenterology, 2008, 135(4): 1114-22. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.06.081.

[28] SANDERSON I R. Growth problems in children with IBD [J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014, 11(10): 601-610. DOI:10.1038/nrgastro.2014.102.