2015年Banff会议肾移植报告解读

王政禄(天津市第一中心医院病理科,天津 300192)

The Banff 2015 Kidney Meeting Report:Current Challenges in Rejection Classification and Prospects for Adopting Molecular Pathology

The ⅩⅢ Banff meeting, held in conjunction the Canadian Society of Transplantation in Vancouver,Canada, reviewed the clinical impact of updates of C4d-negative antibody-mediated rejection (ABMR)from the 2013 meeting, reports from active Banff Working Groups, the relationships of donor-specific antibody tests (anti-HLA and non-HLA) with transplant histopathology, and questions of molecular transplant diagnostics. The use of transcriptome gene sets, their resultant diagnostic classifiers, or common key genes to supplement the diagnosis and classification of rejection requires further consensus agreement and validation in biopsies. Newly introduced concepts include the i-IFTA score, comprising inflammation within areas of fibrosis and atrophy and acceptance of transplant arteriolopathy within the descriptions of chronic active T cell-mediated rejection (TCMR) or chronic ABMR. The pattern of mixed TCMR and ABMR was increasingly recognized. This report also includes improved definitions of TCMR and ABMR in pancreas transplants with specification of vascular lesions and prospects for defining a vascularized composite allograft rejection classification. The goal of the Banff process is ongoing integration of advances in histologic,serologic, and molecular diagnostic techniques to produce a consensus-based reporting system that offers precise composite scores, accurate routine diagnostics,and applicability to next-generation clinical trials.

Abbreviations: aah, hyaline arteriolar thickening;ah, arteriorlar hyalinosis; ABMR, antibody-mediated rejection ; ASHI, American Society for Histocompatibility and Immunogenetics; BWG, Banff Working Groups;cg, glomerular double contours; ci, interstitial fibrosis;ct, tubular atrophy ; cv, vascular fibrous intimal thickening; DGF, delayed graft function ; DSA,donor-specific antibody; DSAST, donor-specific antibody-specific transcript; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; EM,electron microscopy;FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration ; FFPE,for-malin-fixed, paraffin-embedded; g, glomerulitis;GBM, glomerular basement membrane; HS, highly sensitized ; i, inflammation ; IFTA, interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy; i-IFTA, interstitial inflammation in areas of interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy; IHC, immunohistochemistry; IVIG,intravenous immunoglobulin ; mRNA, messenger RNA ; miRNA, microRNA ; MPGN, membranoproliferative glomeru-lonephritis; MVI, microvascular invasion; PAS, periodic acid-Schiff; PCR, polymerase chain reaction ; ptc, peritubular capillaritis; PTC,peritubular capillary ; t, tubulitis; TCMR, T cellmediated rejection ; TG, transplant glomerulopathy;ti, total inflammation; TMA, thrombotic microangiopathy;v,intimal arteritis; VCA, vascularized composite allograft.

Introduction

The ⅩⅢ Banff meeting was held October 5~10, 2015,in Vancouver, Canada, in conjunction with the annual meeting of the Canadian Society of Transplantation. A total of 451 delegates from 28 countries attended the conference, including pathologists, immunologists,physicians, surgeons, and immunogeneticists. The main aims of the 2015 conference were to review the clinical impact of the 2013 changes related to the new diagnostic criteria for antibody-mediated rejection (ABMR)1and to identify the next set of challenges in transplant diagnostics. Given the limitations of the current Banff system, a need for a more integrated diagnostic system,including complementary approaches as a companion to the current morphologic gold standard, are needed.Consequently, the prospects for introducing molecular diagnostics into the Banff classification were a main focus. Accordingly, the Banff 2015 conference was preceded by a full-day premeeting on “Precision Diagnostics” in transplantation. This included presentations from key opinion leaders of the American Society for Histocompatibility and Immunogenetics (ASHI)with the aim to foster collaboration between the societies in transplant diagnostics. This meeting report summarizes the main outcomes from the Banff kidney,pancreas, and vascularized com-posite allograft(VCA) sessions; the main conclusions from the 2015 Banff liver, heart, and lung sessions will be published elsewhere. The XIV Banff meeting will be held jointly with the Catalan Society of Transplantation in Barcelona, Spain, March 27 ~ 31, 2017.

Results From the Banff Working Groups and New Developments

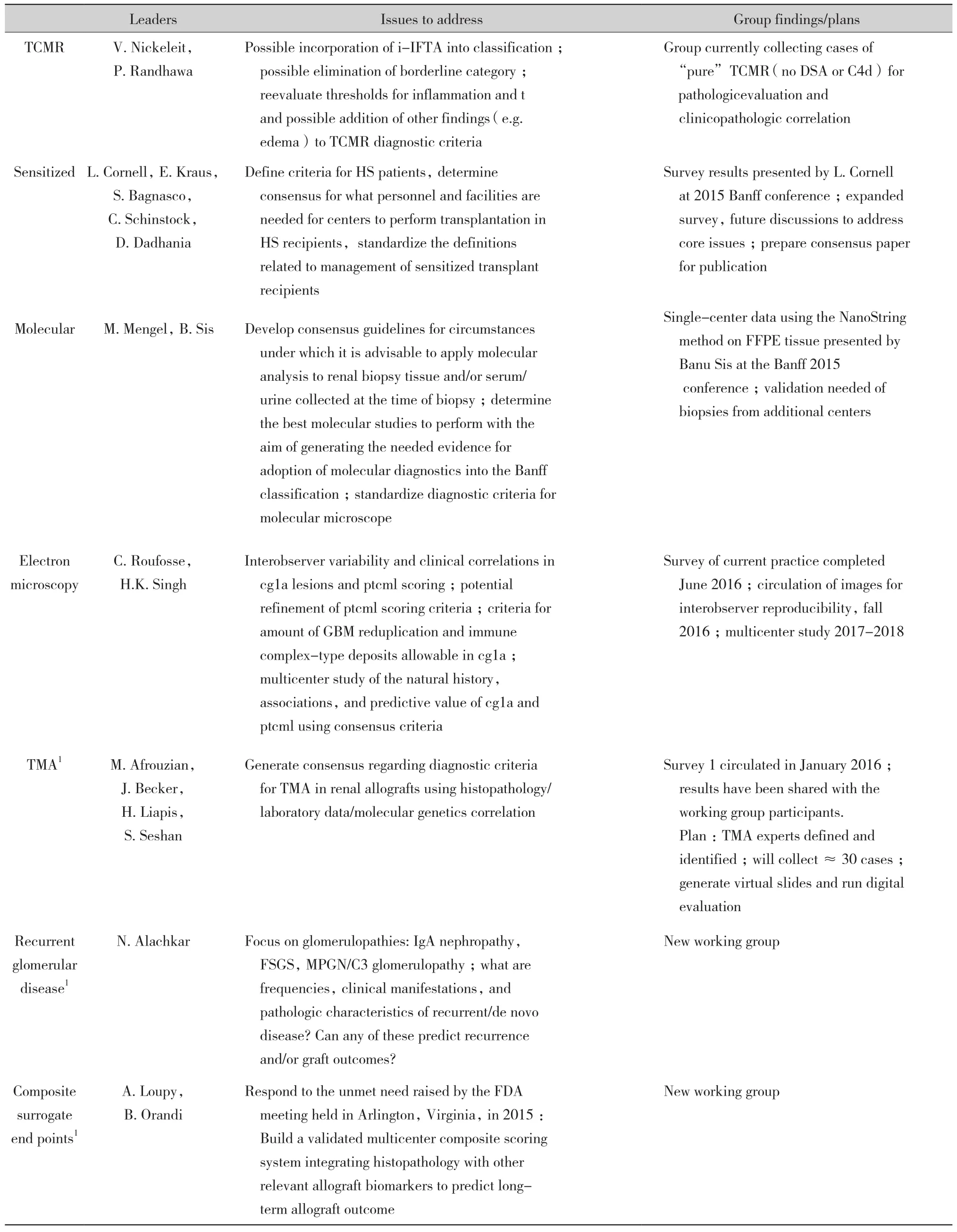

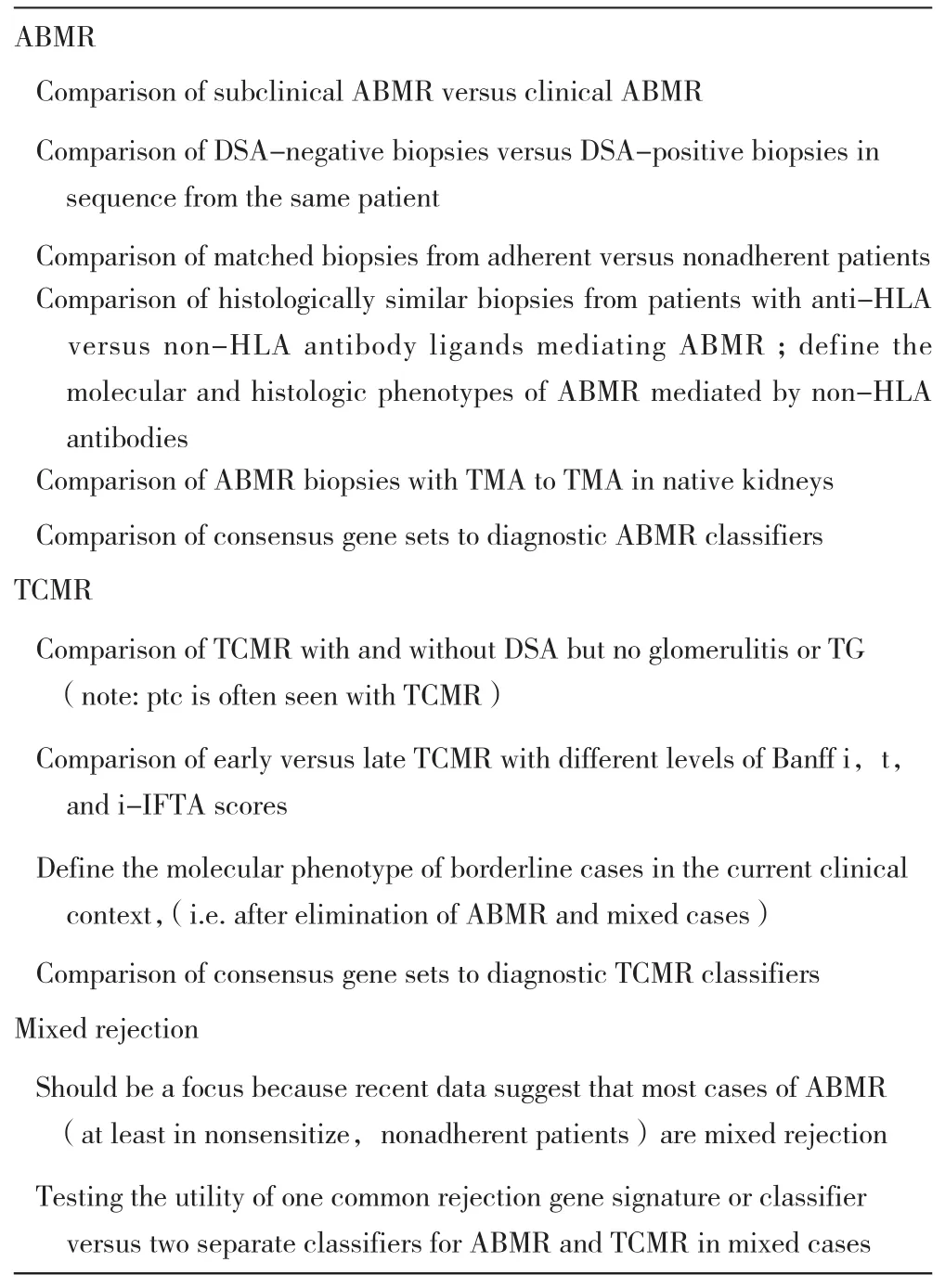

Banff Working Groups (BWGs) have been formed at each of the last four Banff conferences to address and potentially modify specific aspects of the classification2.Their activities are dynamic and goal directed;therefore, the Banff community decided during the 2015 conference to close or suspend working groups whose work has been completed and published, in press, and/ or incorporated into the classification(isolated endarteritis, Banff Initiative for Quality Assurance in Transplantation, fibrosis, implantation biopsy, polyoma virus, C4d-negative ABMR, and glomerular lesions BWGs)1,3-7. The BWG on highly sensitized patients presented the results of three surveys of pathologists, clinicians, and histocompatibility laboratory directors, comprising 193 centers from six continents, and revealed wide heterogeneity among participating centers regarding immune modulation/desensitization practices, timing of kidney allograft protocol biopsies, and testing and reporting of HLA antibody and donor-specific antibody (DSA) levels.The TCMR working group's main aims and related ongoing studies are detailed in Table 1 and are expected to provide novel insights by the next Banff meeting.

Four new BWGs have been formed: (i) thrombotic microangiopathy, (ii) recurrent glomerular diseases,(iii) diagnostic electron microscopy, and (iv)composite surrogate end points. The aim of the latter BWG is to build and validate a composite scoring system integrating histopathology with other relevant allograft biomarkers to predict long-term allograft outcome as a potential end point for next-generation clinical trials in the area. The currently active and new working groups and their aims, leaders, initial findings(if appropriate), and ongoing work are listed in Table 1.As an outlook on future challenges, the Banff process founder Kim Solez gave a keynote address on tissue engineering pathology, a new pathology discipline that will likely play an increasing role in future Banff meetings, as transplant pathologists need to embrace tissue engineering pathology in the era of regenerative medicine8.

New Challenges in Rejection Diagnosis and Classification

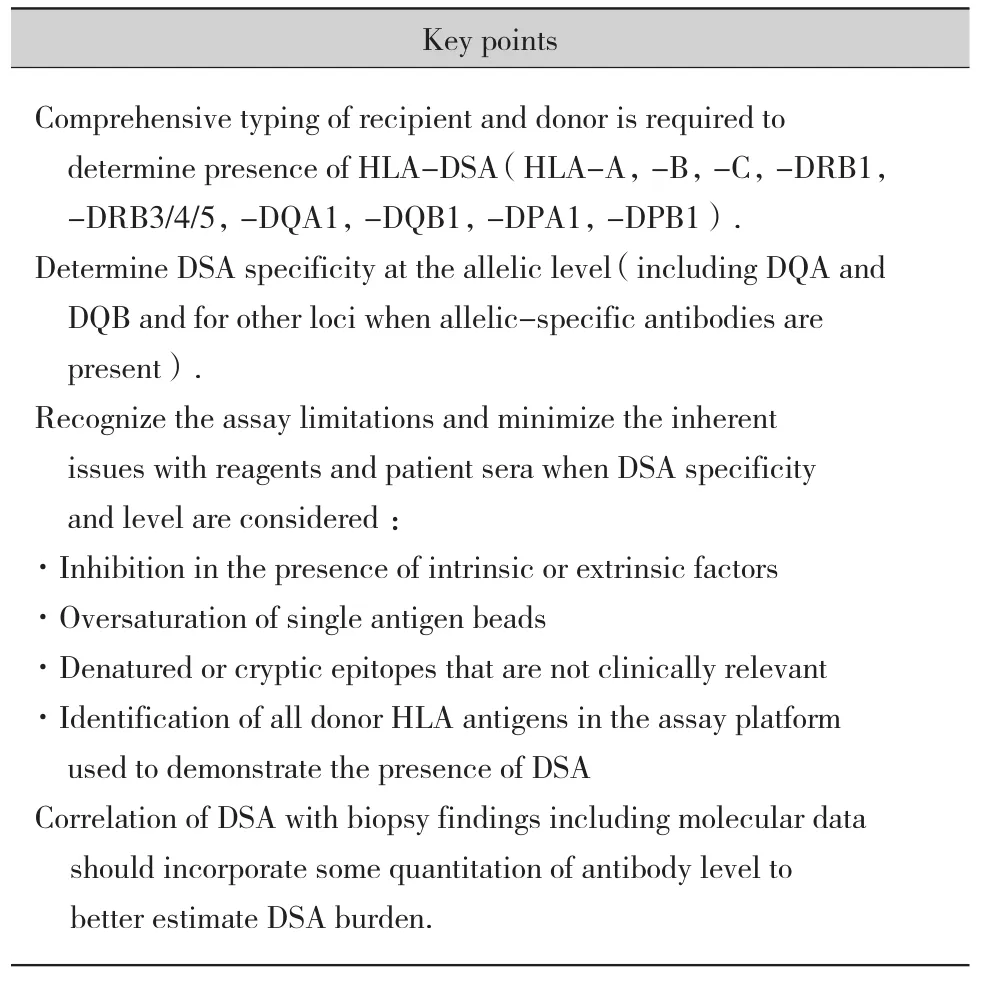

During the 2015 Banff conference, there was lively discussion about diagnostic concerns regarding ABMR, T cell-mediated rejection (TCMR), and mixed rejection in renal allografts. Important new data were presented revealing the heterogeneity of clinical expression of ABMR with consequent difficulties for diagnosis. In addition, important insights were presented by ASHI members on how testing for DSAs and interpretation of results should be included in the Banff classification (Table 2).

Table 1 Summary of active Banff 2015 working groups

Table 2 Key points addressed by the American Society for Histocompatibility and Immunogenetics expert panel during the Banff 2015 conference for improving the current diagnostic system

Recent evidence indicates that subclinical ABMR has important clinical implications, even in non-highly sensi- tized patients with de novo DSAs9. As noted by Orandi et al, “Increasing numbers of transplant physicians are encountering this problem, which may become more common given new therapeutic agents and new organ allocation policies”10.

A growing number of centers perform high-risk renal transplants, thereby intensifying the need for improved assessment of subclinical ABMR11and the clinical implications of its kinetics and response to therapy10.Advances in antibody testing by multiplex bead array assays have greatly enhanced the sensitivity and precision of detection of circulating DSAs12.Accumulating evidence supports the concept that not all DSAs are equivalent and that DSA properties(ability to bind complement or IgG subclass), beyond simple positivity and mean fluorescence intensity,are associated with distinct outcomes and injury phenotypes in preexisting or recurrent as well as de novo DSAs13-20. These distinct DSA properties and their relationship with distinct allograft injury patterns is also increasingly demonstrated in other solid organ transplants such as liver21and heart22. It was also noted that time course, kinetics, and properties of DSA fluctuate15,23. Consequently, interpretation of studies evaluating sera at a single time point, especially late after transplantation, should be interpreted with caution because of potential selection bias24-25. Despite the usefulness of multiplex bead array assays, inherent limitations, technical issues, and lack of available DSA data at the time of biopsy make diagnoses complex.It was reemphasized that non-anti-HLA DSAs can produce allograft injury alone or together with anti-HLA DSAs26-28. These observations raise the question of whether ABMR can be diagnosed in the absence of documented DSAs based on ABMR-related pathology only, namely, microcirculation inflammation, C4d deposition, and vasculitis with or without increased expression of DSA-associated gene sets29-30.

Furthermore, many cases of ABMR in renal allografts,particularly late ABMR associated with de novo DSAs,can present as mixed ABMR and TCMR31. Renal allograft biopsies with microvascular inflammation plus intimal arteritis also frequently show tubulointerstitial TCMR changes9,32. These cases likely represent mixed ABMR and TCMR and, not surprisingly, are often not responsive to treatment for either ABMR or TCMR alone32-33. This may be related in large part to the fact that many cases of late ABMR are associated with nonadherence34. TCMR is also a documented predisposing factor for the future development of de novo DSAs, as demonstrated in two recent studies9,11.More data are needed regarding transplant glomerulopathy (TG) or double contours with or without microcirculation inflammation in terms of disease activity and progression and thus necessity of treatment.A key question discussed during the meeting was whether patients with TG should be treated for active ABMR or whether it should be accepted that these patients will progress to graft loss regardless of treatment. A study by Kahwaji et al35showed in a small cohort of patients, all with TG, that those with active microvascular invasion (MVI) were significantly more likely to show stabilization of graft function with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and rituximab than patients with similar histology who were not treated, whereas patients with TG without active MVI did not benefit from treatment with IVIG and rituximab.The findings suggest that the decision as to whether to treat patients with TG, particularly those with DSAs,should depend on whether there is concurrent active MVI. More recently, a pilot randomized control trial showed that patients with chronic ABMR that responded to complement blockade eculizumab by improved GFR were the ones that had complement (C1q binding)circulating anti-HLA DSAs at the time of diagnosis36.This important issue will be addressed further at Banff 2017.

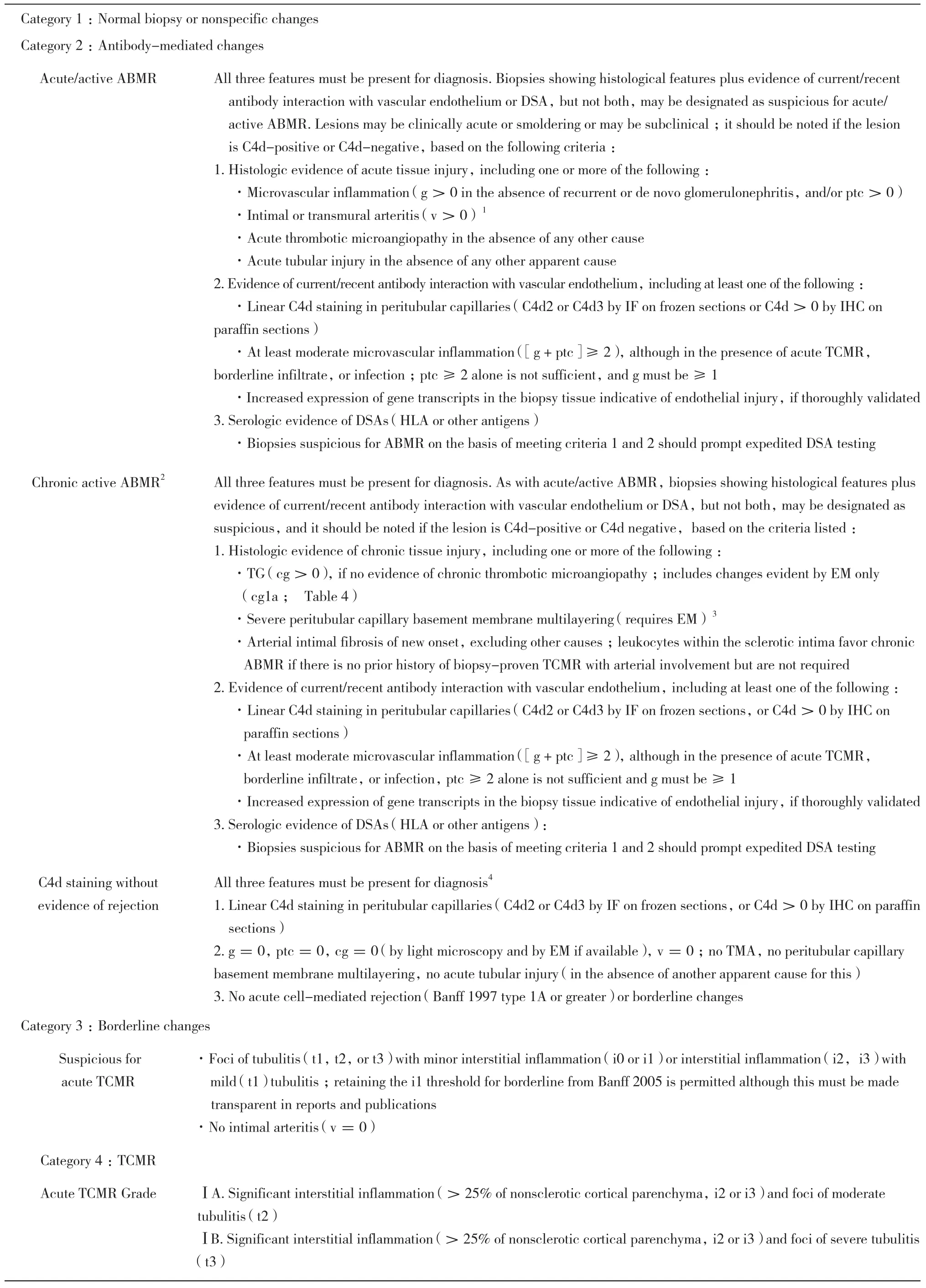

DSA Against HLA or Other Antigens in the Diagnosis of ABMR

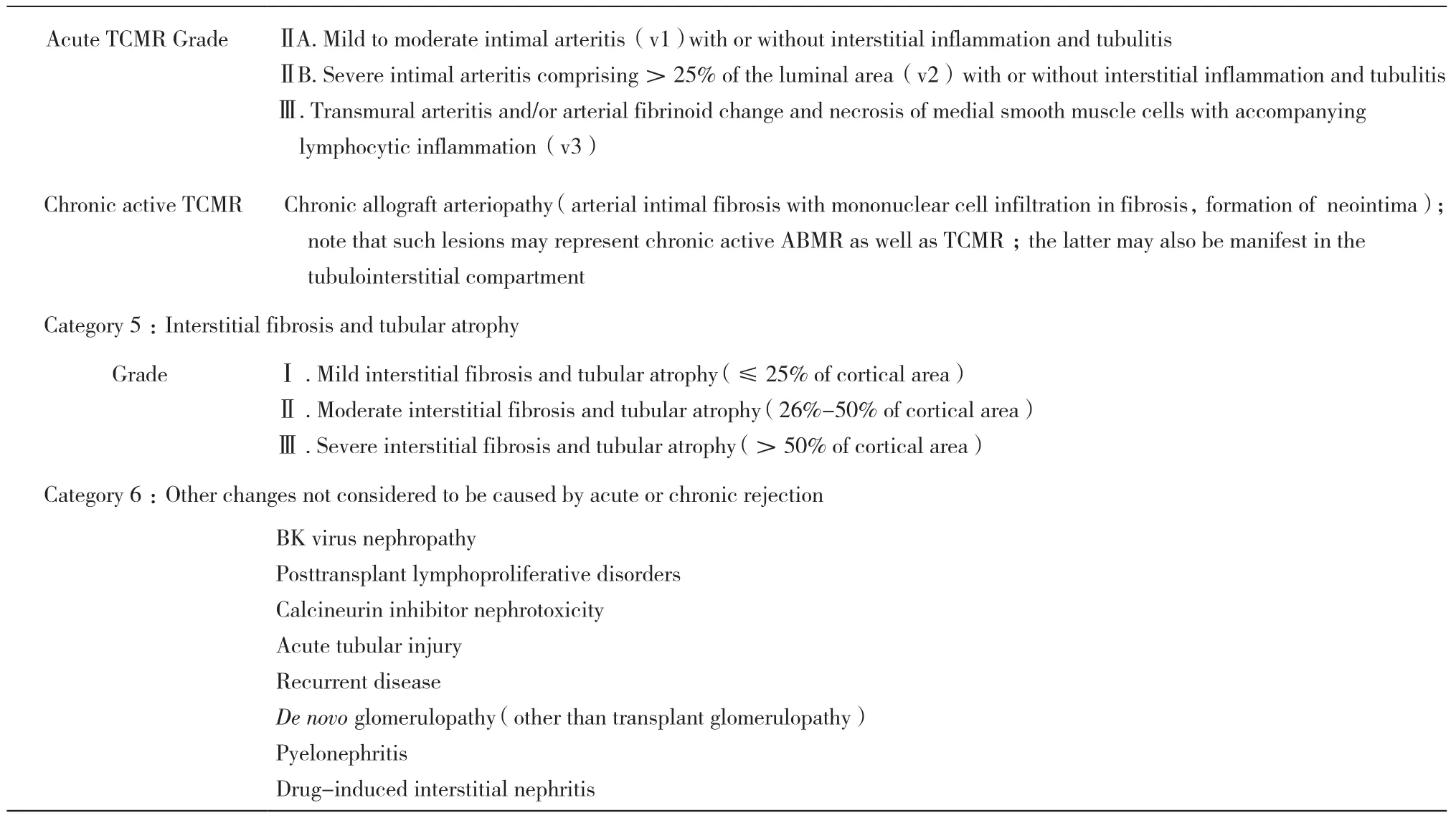

The Banff 2013 classification requires the presence of “serologic evidence of DSA against HLA or other antigens” (criterion 3) for diagnosis of both acute/active and chronic active ABMR; however, peritubular capillary C4d deposition is highly specific for DSA and potentially identifies antibodies against endothelial antigens and DSA currently not tested for in many laboratories (e.g. antibodies to HLA DP, non-HLA antigens). Furthermore, a recent study showed similar graft outcomes, at least in chronic active ABMR, in cases with C4d or DSA and those with C4d and DSA37.The attendees of kidney-specific sessions at Banff 2015 were polled as to whether the requirement for DSA for diagnosis of ABMR can be waived in biopsies showing both morphologic evidence of acute or chronic tissue injury (as defined in criterion 1 of the Banff 2013 classification for acute/active and chronic active ABMR, respectively) and C4d staining in peritubular capillaries; however, the opinion of the majority of the Banff panel (with some dissenters) was that this was not warranted by the current data. It was instead decided to add the following phrase to the classification for both acute/active and chronic active ABMR, as a corollary to criterion 3: “Biopsies meeting the above histologic criteria and showing diffuse or focal linear peritubular capillary C4d staining on frozen or paraffin sections are associated with a high probability of ABMR and should[undergo] prompt expedited DSA testing.” Table 3 summarizes this new addition to the classification, and the complete and most updated Banff classifications for renal allograft diagnoses are shown in Table 3.

A set of transcripts (DSA-specific transcripts [DSASTs])was determined to be differentially expressed in renal allograft biopsies from DSA-positive versus-negative patients29, a finding that was later confirmed independently at a different center30. Consequently,DSASTs have the potential to identify cases of ABMR in patients with non-detectable HLA DSA. It is not clear to what extent, if any, transcript patterns will be affected by prognostically different DSAs,including anti-HLA class Ⅰ versusclass Ⅱ ; antibodies with high versus low mean fluorescence intensity;complement-binding versus non-complement-binding antibodies15-17,19; and antibodies of different IgG subclasses24. Further prospective validation is required.

Chronic Active TCMR and Interstitial Inflammation in Areas of Interstitial Fibrosis and Tubular Atrophy

Table 3 Updated 2015 Banff classification categories

Continued table 3

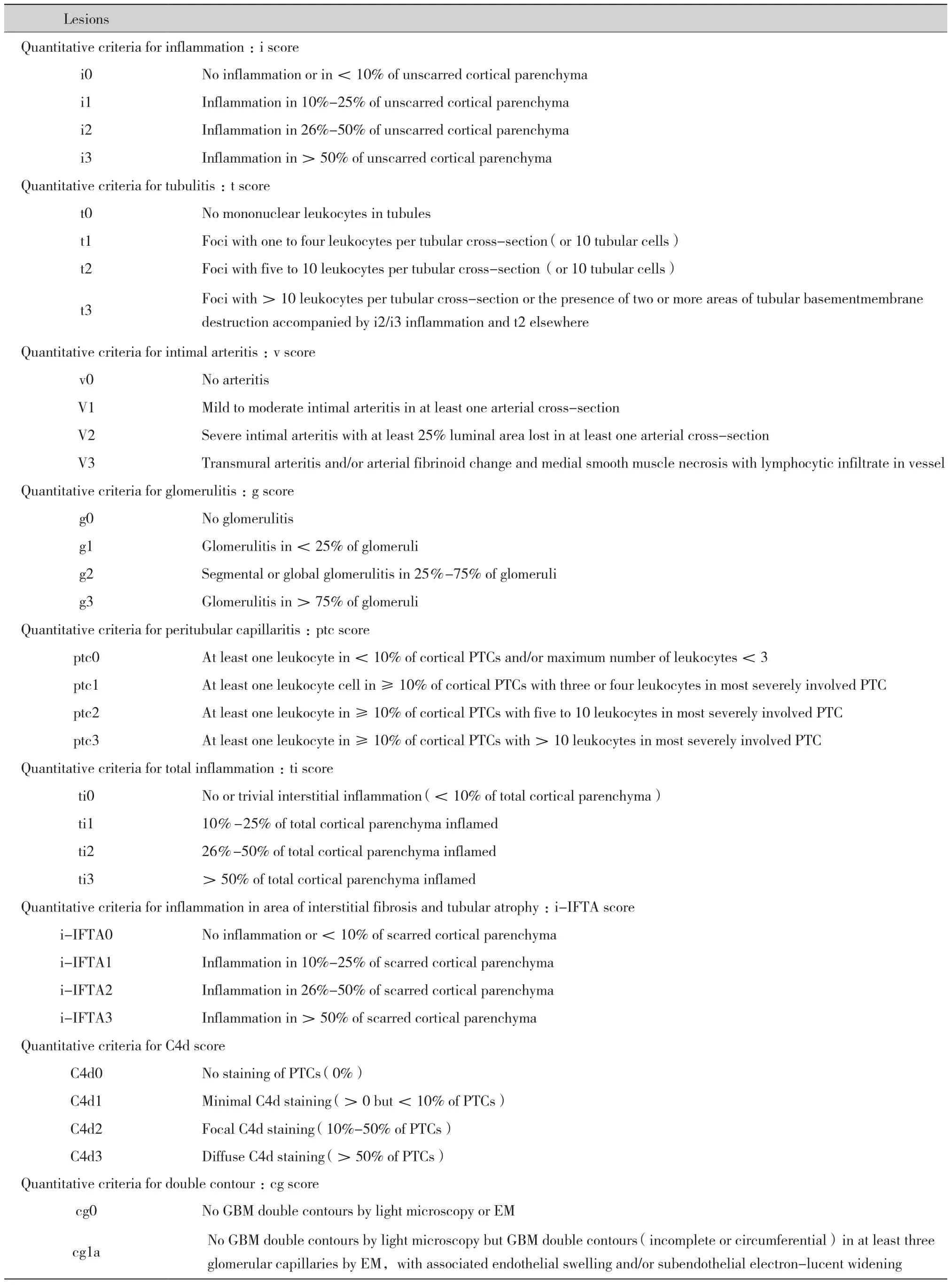

The most recent Banff criteria for chronic active TCMR 38 list only vascular lesions (arterial intimal fibrosis with mononuclear cell infiltration within the sclerotic intima;transplant arteriopathy, Table 3). This is likely neither complete nor fully accurate ; however,sufficient data are currently not available to properly define this diagnosis. Interstitial inflammation in areas of interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy (i-IFTA)was discussed among participants of the Banff meeting as a potential lesion of chronic active TCMR. Although the association of i-IFTA with decreased graft survival is well documented39-41, the pathogenesis of i-IFTA and to what extent this represents a manifestation of TCMR is much less clear. Similarly, the significance of tubulitis in atrophic tubules is unclear. Gene expression studies on microdissected foci of i-IFTA might help assess this. In light of the established deleterious effect on graft survival of i-IFTA and IFTA with Banff inflammation (i) score>0, it was agreed that i-IFTA should be included as part of the Banff lesion scoring. Moreover, i-IFTA should be graded as mild,moderate, or severe based on whether it involves 10%-25%,26%-50%, or > 50%, respectively, of the scarred cortical tissue (Table 4, and supplementary material for scoring criteria). Note that the extent of i-IFTA is not analogous to the Banff total inflammation score, the latter representing the sum of inflammation in scarred and non-scarred areas of the cortex.Consequently, it was decided to modify the Banff 2007 criteria by adding a statement (Table 3, category 4),reflecting findings that lesions of transplant arteriopathy may represent chronic active ABMR42as well as TCMR—also shown in experimental studies43—and that chronic active TCMR may also be manifest in the tubulointerstitial compartment.

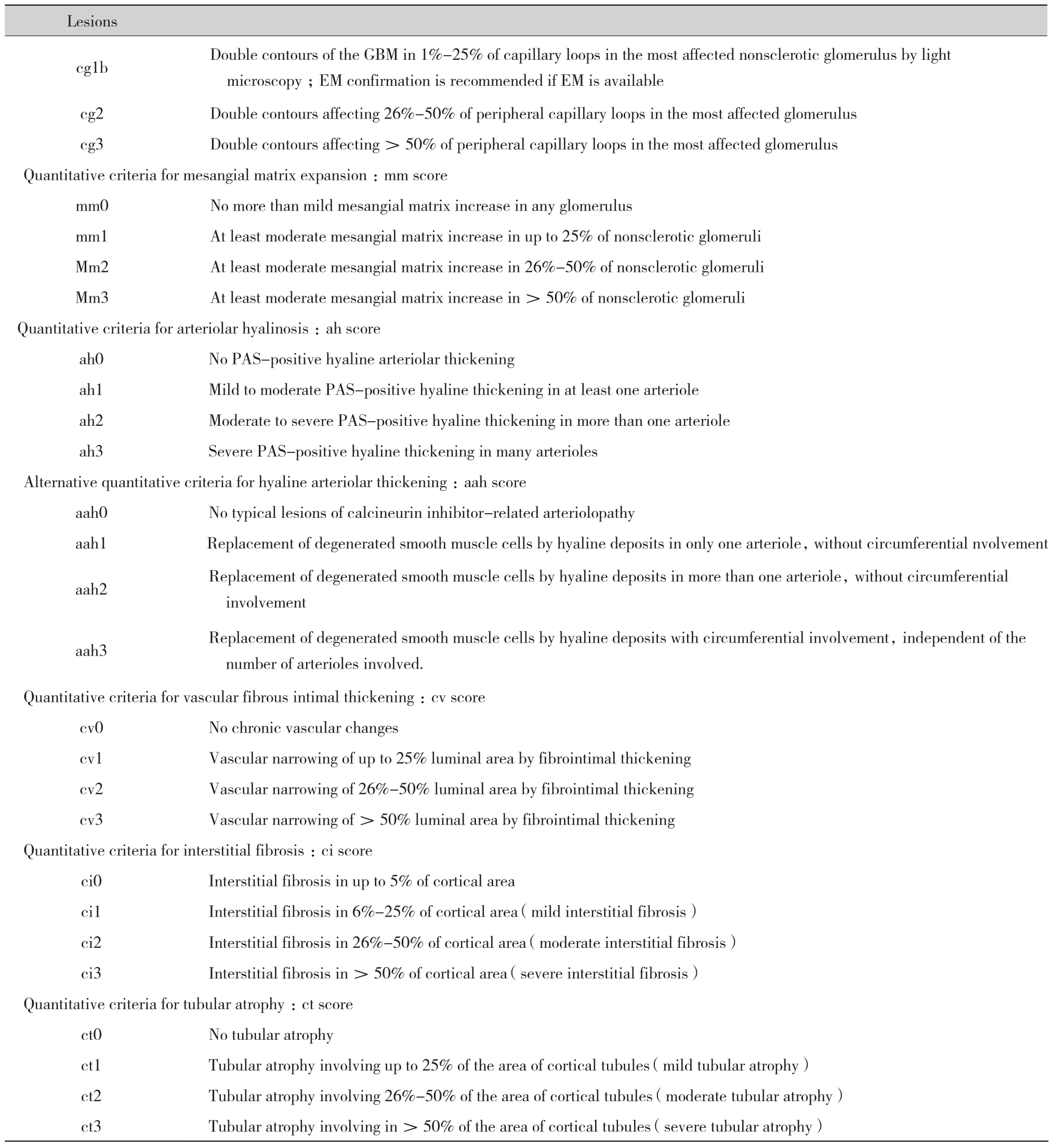

Table 4 Banff lesion grading system

Continued Table 4

During the postmeeting discussion, it was clearly articulated that further studies are needed to understand the significance of i-IFTA in the context of chronic active TCMR before i-IFTA can be included as a diagnostic criterion. In particular, the ongoing work of the borderline/TCMR BWG is expected to generate relevant data in this context.

Prospects for Adopting Molecular Pathology in Renal Allograft Diagnosis

As part of the 2013 revision of the Banff classification for diagnosing ABMR, molecular assessment of transcripts indicative of endothelial injury in the renal allograft biopsy was added as a potential diagnostic criterion1; however, there is no consensus on which transcripts are diagnostic or on the criteria for positivity.Standards for platforms, methods, and reproducibility for such molecular diagnostic assays have not yet been set; such standards are a requirement for robust clinical validation and adoption in diagnostic pathology laboratories. During the 2015 Banff premeeting on“Precision Diagnostics in Transplantation,” current knowledge in the area of molecular transplant diagnostics was reviewed. State-of- the-art presentations on molecular diagnostics in allograft biopsies and body fluids revealed that significant commonalities exist with regard to the molecular phenotype in transplant biopsies from different organ types44. In addition,overlap exists with molecular signatures found in body fluids45. In contrast, there is considerableheterogeneity among published studies with regard to how the molecular phenotype has been assessed and applied as a potential diagnostic and/or predictive tool46.Over the last decade, transplant biopsies, blood,and urine have been studied comprehensively,primarily using transcriptomics, and have led to novel insights into the molecular phenotypes of organ transplants47-53. Current ongoing studies—for example, the INTERCOM studies47-48—are assessing a molecular microscope approach in real time for examining kidney allograft biopsies and comparing the gene expression classifiers and diagnosis to the current gold standard histopathology. This represents a step forward and will generate important results to help guide integration of molecular analysis with morphology. Accordingly, at the 2015 Banff meeting,converging opinion was supported by recent data50,53that molecular transplantation pathology is at the point where it can be translated into clinically relevant and applicable diagnostic tools. The obstacles to be overcome lie in (i) the lack of a true diagnostic gold standard against which new molecular diagnostics can be compared and calibrated (there is no gold standard for serology or histology either); (ii) the fact that data have been generated from heterogeneous cohorts with diagnostic labels assigned based on different iterations of the Banff classification; (iii)the absence of completed prospective, controlled,randomized validation studies; and (iv) the lack of agreement on the transcripts to be measured and how to measure them.

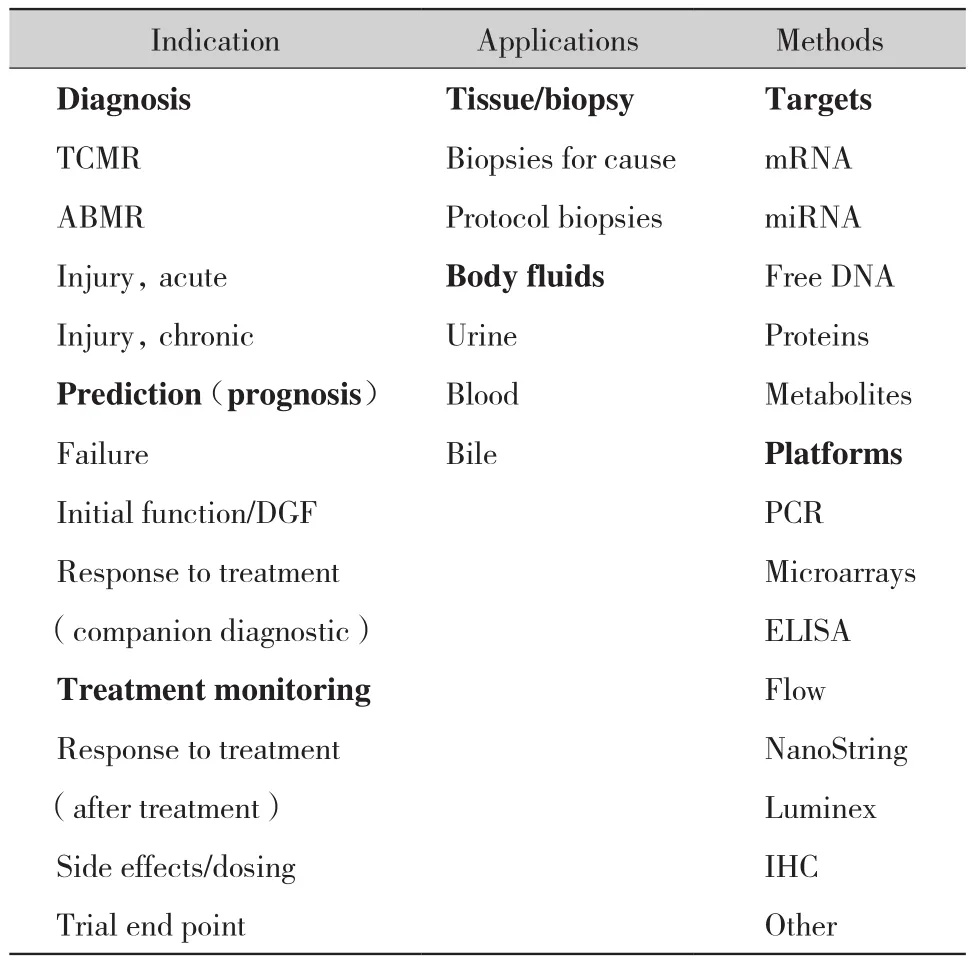

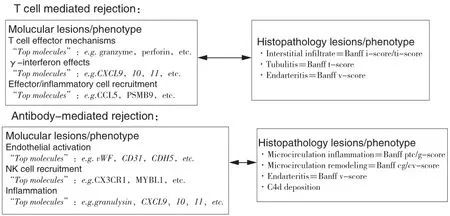

Most disease processes operating in organ transplants represent a spectrum of certain biological processes.Accordingly, our current diagnostic criteria (e.g.for TCMR and ABMR) are built on semiquantitative diagnostic thresholds of lesions associated with a certain phenotype. Such thresholds aim to represent the optimal trade-off between side effects of enhanced treatment (i.e. overimmunosuppression) and the detrimental impact of further disease progression(i.e. underimmunosuppression). A potential path forward would be to generate consensus in molecular transplant diagnostics regarding which molecules are assessed or quantified in what settings(Table 5) and then to develop clinically relevant diagnostic thresholds through retrospective and prospective multicenter validation studies based on standardized assessment of the same molecular lesions in the same clinical context. This approach would be analogous to the Banff consensus process in 1991 for morphologic lesions.Previous research revealed strong associations between certain molecular pathways and well-established Banff histologic lesions (Figure 1). These key molecular pathways can be represented and thus assessed by relatively few molecules from each pathway, either through quantification of respective gene sets or through summarizing such genes in weighted equations as diagnostic classifiers. Generating consensus for sets of molecules or classifiers reflecting certain biological or disease processes related to the established histologic Banff lesions would enable us to assess and validate their clinical value. In this regard, the most robust evidence is currently available for the association among antibody-mediated injury; microcirculation inflammation; and increased expression of endothelial,NK cell, and inflammation-associated transcripts in the allograft29,54-56.

Table 5 Key areas for which consensus needs to be generatedand validated to adopt molecular diagnostics into the Banff classification

Figure 1 Molecular lesions and their corresponding histologic lesions in T cell-mediated rejection and antibody-mediated rejection in kidney allografts. cg, glomerular double contours;cv,vascular fibrous intimal thickening;i,inflammation;ptc,peritubular capillaritis;ti,total inflammation ; v,intimal arteritis.

Discussion of the above approach took place at the 2015 Banff meeting and continued afterward via e-mail exchange among the key opinion leaders. From these interactions, key next steps toward adopting molecular diagnostics into transplantation pathology were identified and are summarized (Table 6):

Table 6 Identified knowledge gap in the adoption process for molecular transplant diagnostics

1. The overwhelming majority of those who commented support pursuing the generation of molecular consensus gene sets (or classifiers) from the overlap between published gene lists, adding key genes based on pathogenesis-based association with the main clinical indications and phenotypes (TCMR, ABMR).

2. More collaborative multicenter studies are needed(Table 6) to close existing knowledge gaps before Banff can “officially” adopt specific molecular diagnostics as part of the classification.

3. Consensus must be generated on gene sets, which can be studied further in a multicenter setting.

4. Results from such studies should be reviewed at future Banff meetings as part of an ongoing consen- sus process for molecular diagnostics.

Once consensus for gene sets and/or classifiers for molecular biopsy assessment is achieved, prospective and retrospective validation trials can be initiated.Similar to the validation of histologic Banff lesions and diagnostic rules established in 1991, only multicenter validation of different diagnostic approaches with hard clinical end points (e.g. allograft survival, response to treatment) can establish clinically useful diagnostic thresholds. In the absence of a true diagnostic gold standard, adoption of molecular diagnostics can only be accomplished in a stepwise and iterative approach over time including constant revisiting and refinement of current molecular consensus as new knowledge emerges.

Summary of the Banff Pancreas Session

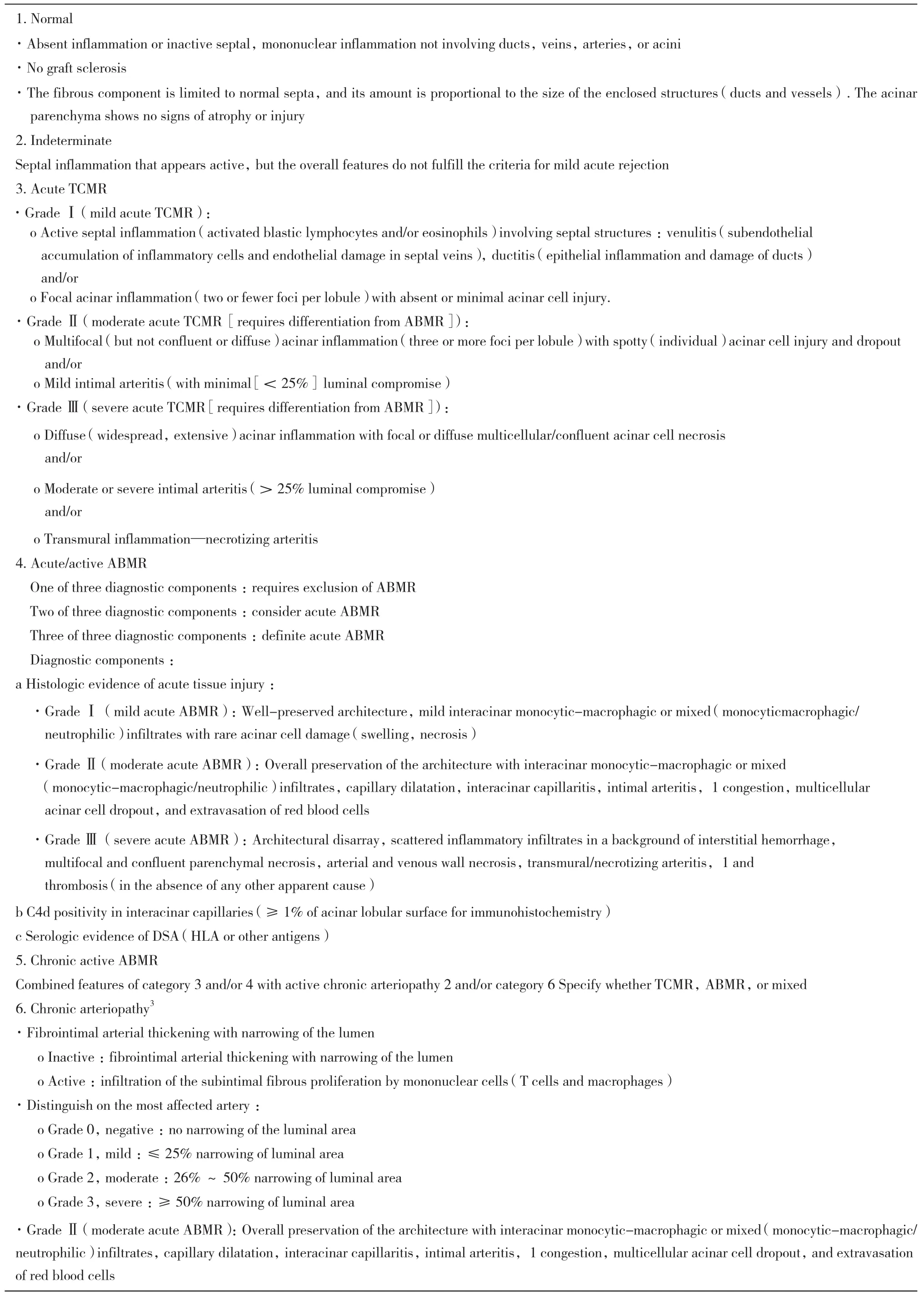

Three main topics (Table 7) were emphasized at the pancreas transplant session: (i) discussion of controversial morphologic aspects, (ii) progress made with the working groups since the 2013 meeting,and (iii) encouragement of data regarding the utility of endoscopic duodenal cuff biopsies as surrogates of biopsies of the pancreas transplant. Data were presented showing that a normal duodenal cuff biopsy accurately predicts absence of TCMR in the pancreas parenchyma. A study of duodenal cuff biopsies showed a high incidence of cytomegalovirus infection in these samples that we do not know how to interpret at this stage. Furthermore, data from detailed morphologic studies on pale acinar nodules in native and transplant pancreas biopsies, which are still of unclear etiology and clinical significance,were presented57. A study was presented at the Banff session that showed simultaneous pancreas and kidney transplant biopsies demonstrating high concurrence between acute ABMR in both organs and significant discrepancy between organs for TCMR. Modifications to the Banff pancreas allograft pathology schema were made after consensus was reached following e-mail circulation to the BWG for Pancreas Pathology and via discussions during the meeting. Main updates include incorporation of acute ABMR grading, improved definitions for TCMR and ABMR, specifica tion of vascular lesions, and inclusion of b cell islet toxicity in the category of islet pathology. In the second part of the session, key opinion leaders discussed morphologic and clinical aspects of graft loss in whole pancreas transplants as well as islet transplantation. It was concluded that better understanding of the etiology of graft loss represents an unmet need. This will require systematic integration of morphologic (pathology),serologic (DSAs and autoantibodies), and clinicalfunctional (e.g. oral glucose tolerance test) parameters for studying the cause and incidence of pancreas transplant failure.

Summary of the VCA Session

The VCA session included speaker presentations and discussion. Focal points of the former were ABMR after face transplantation58, graft vasculopathy in the skin59, cutaneous changes among transplant patients,and the expansion of the Banff VCA scoring system.The discussion included challenges to the Banff VCA system, immunohistochemistry markers, specimen adequacy, and differential diagnoses. Collaborative efforts were discussed, and the working group concentrated on the standardization of a document for the retrospective and prospective collection of data.The group will reconvene at an international workshop on VCA histopathology with the goals of continuing discussions of the refinement of the Banff VCA system, the standardized form, and the development of a consensus document that would be accessible worldwide. The goal is to compile data and to review it at the Banff 2017 meeting.

Table 7 Updated Banff pancreas allograft rejection grading schema

Continued Table 7

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the instrumental support from the Roche Organ Transplantation Research Foundation Grant 608390948 awarded to Dr. Kim Solez, which allowed establishing the Banff Foundation for Allograft Pathology. The joint 2015 Banff and Canadian Transplant Society meeting acknowledges the receipt of sponsorship from Astellas, Alexion,Novartis, One Lambda, Renal Pathology Society,American Society of Transplantation, Wiley, Qiagen,Canadian Institute for Health Research, Immucor,Bridge to Life, Organ Recovery Systems, Transplant Connect, Glycorex Transplantation, Transpath Inc.,and the University of Alberta.

Disclosure

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Data S1 :The Banff Manual: Definitions and Rules

This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License, which permits use and distribution in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, the use is non-commercial and no modifications or adaptations are made.

第十三届Banff会议在加拿大温哥华举行,来自28个国家的共计451名病理学家、免疫学家、临床及外科专家参加本次会议。会议首先回顾分析了2013年修改的抗体介导性排斥(antibodymediated rejection,ABMR)诊断标准对临床的影响,随后,指出了目前Banff诊断标准存在的一定局限性并讨论将“分子诊断”引入分类标准的前景。会议对Banff工作组(Banff work group, BWG)的工作进行总结和规划,指出:BWG在连续4次的工作会议中制定和修改了包括孤立性动脉炎、初始移植物质量,纤维化、供肾活检、多瘤病毒、C4d阴性的ABMR以及肾小球病变等诊断及分类的具体标准,因此,会议决定暂停上述小组的工作。“高致敏患者”工作组,提出了关于免疫调节/脱敏、活检时间以及人类白细胞抗原(human leukocyte antigen, HLA)抗体和供者特异性抗体(donor specific antibody, DSA)水平相关报告 ;“TCMR”工作组报告了研究情况和主要目标(原文表2),预计将在2017年Banff会议上提供新的结论。本次会议形成4个新BWG,包括“血栓性微血管病变”、“复发性肾小球疾病”、“电子显微镜诊断”和“综合替代终点”。 BWG的最终目标是整合病理学和相关生物标志物,建立一个综合评分系统,以预测移植物长期结果。新BWG的目标、领导者、初步结果和正在进行的工作(原文表2)。BWG的创始人Kim Solez认为“组织工程病理学”是一个崭新的病理学,可能会在未来发挥更大的作用。

1 排斥反应诊断和分类的新挑战

会议期间对ABMR、T细胞介导的排斥(T-cell mediated rejection, TCMR)和混合性排斥的诊断进行了讨论,提出由于ABMR的临床表现具有异质性,会给诊断带来困难。美国组织相容性和免疫遗传学协会(American Society for Histocompatibility and Immunogenetics, ASHI)提出了对DSA检测结果以及其在Banff分类中的解释(原文表2),表明在非高致敏患者中,新发DSA在亚临床的ABMR具有重要意义,因此,有必要加强对亚临床ABMR的观察以及对治疗效果的评估,进一步明确其临床意义。由于多重微珠阵列的抗体检测的进展,提高了对循环DSA检测的敏感性和准确性,发现并非所有的DSA都具有同等效应,除了DSA的阳性和强度之外,DSA的性质(结合补体或IgG亚型的能力)和预先存在或复发以及新生的抗体与损伤存在关联,这些现象在其他实体器官移植(肝脏、心脏)中得到证实。报告中还提到DSA的持续时间、动力学和性质具有波动性,因此,在单个时间点(特别是移植后期),对于检测结果的解释应谨慎。由于非抗HLA-DSA可以单独或与抗HLADSA共同对移植物造成损伤,因此,在仅有ABMR相关的病理表现(如微循环炎症、C4d沉积和血管炎)而没有DSA结果时ABMR能否被诊断仍需讨论。此外,在肾移植中,特别是与新发DSAs相关的晚期病例,ABMR可以混合TCMR共同存在,在出现微血管炎和动脉内膜炎的活检中也常常出现小管/间质性TCMR的病变,这些病例可能代表混合性ABMR和TCMR,通常对单一的ABMR或TCMR治疗无效。会议认为移植肾小球病 (transplant glanerulopathy, TG)患者是否需要接受积极的抗ABMR治疗,特别是存在DSA的患者中,应该取决于是否伴有活动性MVI。

2 针对HLA或其他抗原的DSA对ABMR诊断的影响

Banff 2013分类标准中提出:针对HLA或其他抗原的DSA可作为急/慢性活动性ABMR诊断的血清学证据。然而,肾小管周围毛细血管的C4d沉淀,是DSA高度特异指证,本次会议对DSA和肾小管周围毛细血管C4d染色作为诊断ABMR的必要性进行了讨论,多数研究者认为目前的数据不能证实,进而增加“活检符合组织学诊断标准和肾小管周围毛细血管C4d的染色阳性的患者有极大可能诊断ABMR,但需要进一步行DSA检测”并总结了新的诊断标准(原文表3)。DSASTs在DSA阳性和阴性患者中表达差异在许多中心被证实,因此,DSASTs可识别哪些未检测出HLA DSA的ABMR患者。目前,转录模式、抗HLA Ⅰ类和Ⅱ类、 平均荧光强度,补体/非补体结合抗体以及不同IgG亚类等对不同DSA患者预后的影响有待进一步研究。

3 慢性活动性TCMR与间质纤维化和肾小管萎缩区域的炎症

Banff标准对慢性活动TCMR仅列出血管病变(单个核细胞浸润纤维化动脉),这既不完整也不准确,提出并讨论了间质纤维化和肾小管萎缩区域的炎 症(interstitial inflammation in areas of interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy, i-IFTA)应作为慢性活动性TCMR的潜在病变,应作为Banff病变评分一部分,并依据i-IFTA占皮质纤维化区域分为轻度(≤25%)、中度(26%~50%)和重度(>50%),需要注意的是i-IFTA和i评分标准于不一致,其炎症评估是以纤维化区域为主。

4 分子病理学在肾移植诊断中的前景

在2013 ABMR Banff诊断标准中提出了内皮损伤的分子学评估可作为潜在标准,但由于目前对于分子诊断的标准化平台、方法和可重复性尚未建立,因此,尚未达成诊断共识。在会议前的“移植精准医疗”讨论中,对目前分子学领域进行了综述,研究提示不同器官移植组织的分子表型存在共性,而且在体液中发现重叠的分子指征,但以现有研究结论尚难以作为一个潜在的评估和应用标准。利用转录组学在活检、血液和尿液进行了全面研究,发现了器官移植中的新的分子表型,有助于指导分子分析与形态学的整合。目前,移植分子/病理学研究转化为临床诊断工具还解决一些难题。当前的诊断标准(例如,TCMR和ABMR)是建立在与某种表型相关的病变的半定量诊断阈值上,未来方向是在分子诊断中产生共识(原文表5),然后,通过基于相同分子标准化评估的回顾性和前瞻性多中心验证研究,在相同的临床背景下明确临床相关的诊断阈值。某些分子途径和组织学病变之间的关联(见原文图1),最有力的证据可用于抗体介导的损伤之间的关联,微循环炎症以及内皮细胞,NK细胞和炎症相关转录物在同种异体移植物中的表达增加。在没有真正的诊断“金标准“下,分子诊断的采用只能在逐步完成,包括新知识的出现和对当前分子共识的不断认识和优化。

5 胰腺和血管化复合同种异体移植物(vascularized composite allograft,VCA)

胰腺移植会议讨论了形态学、工作进展和内窥镜活检3个主题(原文表7),提出十二指肠套囊活检能够准确地预测胰腺实质中TCMR和发现巨细胞病毒(cytomegaoviyns virus, CMV)感染率很高。对自体和移植胰腺的淡然腺泡结节进行了详细的形态学描述,但仍然不清楚其病因和临床意义。研究表明,胰腺和肾脏联合移植后的活检显示两种器官急性ABMR之间是高度一致,TCMR存在显着差异。对胰腺移植病理学诊断模式进行了修改,包括急性ABMR分级,完善TCMR和ABMR的定义、血管损伤定义以及胰岛细胞病理学中胰岛B细胞毒性的研究(原文表5)。通过形态学(病理学),血清学(DSA和自身抗体)和临床功能(例如口服葡萄糖耐量试验)参数的统一结合来研究胰腺移植失败的原因和发生率,这样可以更好地理解移植失

VCA重点讨论了面部移植后的ABMR、血管病变、皮肤变化以及Banff VCA评分系统的扩充,包括免疫组织化学标志物、样本充足性和鉴别诊断。工作组将继续讨论Banff VCA系统的改进,采用标准化的形式,制定可获得共识的文件及数据并在2017年Banff会议上进行审定。