第五次全国幽门螺杆菌感染处理共识报告

中华医学会消化病学分会幽门螺杆菌和消化性溃疡学组 全国幽门螺杆菌研究协作组

刘文忠1 谢 勇2 陆 红1 成 虹3 曾志荣4 周丽雅5 陈 烨6 王江滨7 杜奕奇8 吕农华2*

上海交通大学医学院附属仁济医院消化科1(200001) 南昌大学第一附属医院消化科2北京大学第一医院消化科3 中山大学附属第一医院消化科4 北京大学第三医院消化科5南方医科大学南方医院消化科6 吉林大学中日联谊医院消化科7 第二军医大学附属长海医院消化科8

·共识与指南·

第五次全国幽门螺杆菌感染处理共识报告

中华医学会消化病学分会幽门螺杆菌和消化性溃疡学组 全国幽门螺杆菌研究协作组

刘文忠1谢 勇2陆 红1成 虹3曾志荣4周丽雅5陈 烨6王江滨7杜奕奇8吕农华2*

上海交通大学医学院附属仁济医院消化科1(200001) 南昌大学第一附属医院消化科2北京大学第一医院消化科3中山大学附属第一医院消化科4北京大学第三医院消化科5南方医科大学南方医院消化科6吉林大学中日联谊医院消化科7第二军医大学附属长海医院消化科8

由中华医学会消化病学分会幽门螺杆菌(Hp)和消化性溃疡学组主办的“幽门螺杆菌感染处理Maastricht-5共识研讨会暨第五次全国幽门螺杆菌感染处理共识会” 于2016年12月15~16日在浙江杭州召开。我国消化病学和Hp 研究领域的专家和学组成员共80余人出席了会议。

自2012年第四次全国Hp感染处理共识会议以来[1],国际上先后发表了3个重要的相关共识,分别是《幽门螺杆菌胃炎京都全球共识》[2](以下简称京都共识)、《多伦多成人幽门螺杆菌感染治疗共识》[3](以下简称多伦多共识)和《幽门螺杆菌感染处理的Maastricht-5共识》[4](以下简称Maastricht-5共识)。京都共识强调了Hp胃炎是一种感染性疾病,Hp相关消化不良是一种器质性疾病,根除Hp可作为胃癌一级预防措施。多伦多共识是成人根除Hp治疗的专题共识。Maastricht-5共识是最具影响的国际共识,内容涉及Hp感染处理各个方面。国内举行了相应的研讨会[5]借鉴学习这些国际共识,在借鉴这些共识的基础上,结合我国国情,制订了我国第五次Hp感染处理共识。制定本共识的方法如下:

1. 成立共识筹备小组:按照中华医学会相关要求[6],成立第五次全国Hp感染处理共识会议工作小组,设立首席专家、组长、副组长和组员,分工负责共识会议筹备工作。

2. 共识相关“陈述(statements)”的构建:通过系统的文献检索,结合Hp感染处理中的关键或热点问题,构建了相关“陈述”。“陈述”起草过程中参考了PICO(population, intervention, comparator, outcome)原则[6],并借鉴了国际相关共识[2-4]。

3. 证据质量和推荐强度的评估:采用GRADE (grading of recommendations assessment, development, and evaluation) 系统评估证据质量(quality of evidence)和推荐强度(strength of recommendation)[7]。证据质量分为高质量、中等质量、低质量和很低质量4级,推荐强度分为强推荐(获益显著大于风险,或反之)和条件推荐(获益大于风险,或反之)2级。证据质量仅是决定推荐强度的因素之一,低质量证据亦有可能获得强推荐[3]。

4. 共识达成过程:采用Delphi方法达成相关“陈述”的共识。构建的“陈述”先通过电子邮件方式征询相关专家意见,通过两轮征询后,初步达成共识的“陈述”在2016年12月16日会议上逐条讨论,并进行了必要的修改。参会人员中21位核心成员参加了“陈述”条款的最终表决。应用电子系统采用无记名投票表决,表决意见分成6级:①完全同意;②同意, 有小保留意见;③同意,有大保留意见;④反对,有大保留意见;⑤反对,有小保留意见;⑥完全反对。表决意见①+②>80%属于达成共识。

本共识内容分为Hp根除指征、诊断、根除治疗、Hp感染与胃癌、特殊人群Hp感染、Hp感染与胃肠道微生态6部分,共48条“陈述”。

一、Hp根除指征

【陈述1】不管有无症状和并发症,Hp胃炎是一种感染性疾病。

证据质量:高;推荐强度:强;共识水平:100%。

尽管Hp感染者中仅约15%~20%发生消化性溃疡[8],5%~10%发生Hp相关消化不良[9],约1%发生胃恶性肿瘤[胃癌、黏膜相关淋巴样组织(MALT)淋巴瘤][10],多数感染者并无症状和并发症,但所有Hp感染者几乎均存在慢性活动性胃炎(chronic active gastritis),亦即Hp胃炎[11-12]。Hp感染与慢性活动性胃炎之间的因果关系符合Koch原则[13-14]。Hp感染可在人-人之间传播[15]。因此Hp胃炎不管有无症状和(或)并发症,是一种感染性疾病,根除治疗对象可扩展至无症状者[2,4]。

【陈述2】根除Hp的获益在不同个体之间存在差异。

证据质量:中;推荐强度:强;共识水平:100%。

根除Hp可促进消化性溃疡愈合和降低溃疡并发症发生率[16],根除Hp可使约80%早期胃MALT淋巴瘤获得缓解[17]。与无症状和并发症的Hp感染者相比,上述患者根除Hp的获益显然更大。胃癌发生高风险个体[有胃癌家族史、早期胃癌内镜下切除术后和胃黏膜萎缩和(或)肠化生等]根除Hp预防胃癌的获益高于低风险个体。多次根除治疗失败后治疗难度增加,应再次评估治疗的获益-风险比,进行个体化处理[1]。

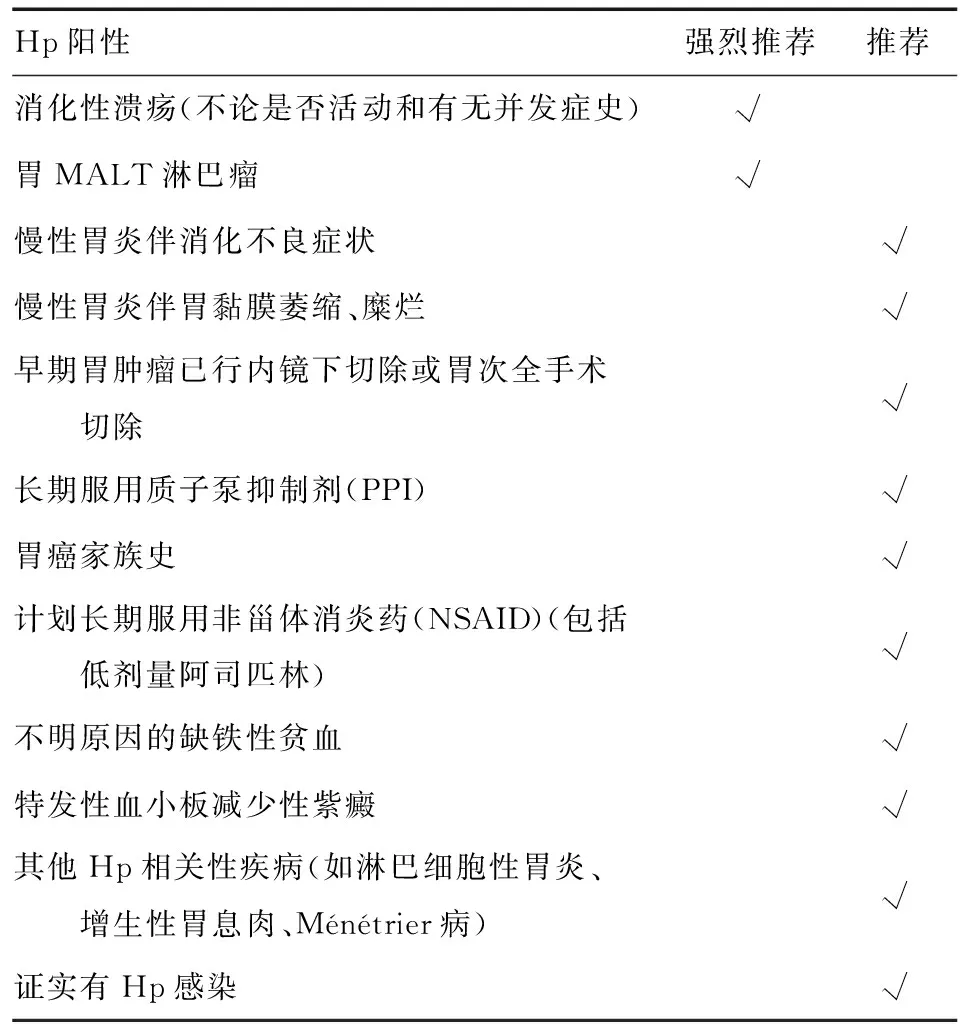

Hp胃炎作为一种感染性疾病,似乎所有Hp阳性者均有必要治疗。但应该看到,目前我国Hp感染率仍达约50%[18],主动筛查所有Hp阳性者并进行治疗并不现实。现阶段仍然需要根除指征(表1),以便主动对获益较大的个体进行Hp“检测和治疗(test and treat)”。

表1 Hp根除指征

【陈述3】Hp “检测和治疗”策略对未经调查消化不良(uninvestigated dyspepsia)处理是适当的。这一策略的实施应取决于当地上消化道肿瘤发病率、成本-效益比和患者意愿等因素。该策略不适用于年龄>35岁、有报警症状、有胃癌家族史或胃癌高发区患者。

证据质量:中;推荐强度:条件;共识水平:100%。

Hp “检测和治疗”是一种用非侵入性方法(尿素呼气试验或粪便抗原试验)检测Hp,阳性者即给予根除治疗的策略,国际上广泛用于未经调查消化不良的处理[19]。这一策略的优点是无需胃镜检查,缺点是有漏检上消化道肿瘤风险。在胃镜检查费用高和上消化道肿瘤发病率低的地区实施有较高成本-效益比的优势[20]。这一策略也是根除Hp作为消化不良处理一线治疗的措施之一[2,21]。我国胃镜检查费用较低,胃癌发病率存在显著的地区差异。这一策略不适用于胃癌高发区消化不良患者。在胃癌低发区实施这一策略,排除有报警症状和胃癌家族史者,并将年龄阈值降至<35岁可显著降低漏检上消化道肿瘤的风险[22]。我国胃镜检查普及度广,胃镜检查作为备选或首选,可取决于患者意愿。

【陈述4】Hp胃炎可在部分患者中引起消化不良症状。

证据质量:高;推荐强度:强;共识水平:100%。

【陈述5】在作出可靠的功能性消化不良诊断前,必须排除Hp相关消化不良。

证据质量:高;推荐强度:强;共识水平:100%。

【陈述6】Hp胃炎伴消化不良症状的患者,根除Hp后可使部分患者的症状获得长期缓解,是优选选择。

证据质量:中;推荐强度:强;共识水平:100%。

Hp胃炎可在部分患者中产生消化不良症状,主要证据包括:①Hp感染者消化不良发生率高于无感染者[9];②志愿者吞服Hp后诱发胃炎和消化不良症状[13-14];③根除Hp可使部分患者的消化不良症状缓解,疗效高于安慰剂[23];④ Hp胃炎存在胃黏膜炎性反应、胃肠激素和胃酸分泌水平改变,影响胃十二指肠敏感性和运动[24],与消化不良症状产生相关。

Hp胃炎伴消化不良症状患者根除Hp后消化不良变化可分成三类:①症状得到长期(> 6个月)缓解;②症状无改善;③症状短时间改善后又复发。目前认为第一类患者应属于Hp相关消化不良(Hp-associated dyspepsia),这部分患者的Hp胃炎可以解释其消化不良症状,应属于器质性消化不良[2,25-26]。后两类患者虽然有Hp感染,但根除Hp后症状无改善或仅有短时间改善(后者不排除根除方案中PPI作用),因此仍可作为功能性消化不良。

2005年美国胃肠病学会消化不良处理评估报告[23]指出:总体而言,在功能性消化不良治疗中已确立疗效(与安慰剂治疗相比)的方案是根除Hp和PPI治疗;对于Hp阳性患者根除治疗是最经济有效的方法,因为一次治疗可获得长期效果。功能性胃肠病罗马Ⅳ也接受上述观点[26]。京都共识推荐根除Hp作为消化不良处理的一线治疗[2],因为这一策略不仅疗效相对较高,而且可以预防消化性溃疡和胃癌,减少传染源。

【陈述7】Hp感染是消化性溃疡的主要病因,不管溃疡是否活动以及是否有并发症史,均应检测和根除Hp。

证据质量:高;推荐强度:强;共识水平:100%。

消化性溃疡包括十二指肠溃疡和胃溃疡,是1994年全球首次Hp感染处理共识推荐的根除指征[27]。Hp感染是90%以上十二指肠溃疡和70%~80%胃溃疡的病因,根除Hp可促进溃疡愈合,显著降低溃疡复发率和并发症发生率[16,28]。根除Hp使Hp阳性消化性溃疡不再是一种慢性、复发性疾病,而是可以完全治愈[29]。

【陈述8】根除Hp是局部阶段(Lugano Ⅰ/Ⅱ期)胃MALT淋巴瘤的一线治疗。

证据质量:中;推荐强度:强;共识水平:100%。

Hp阳性的局部阶段胃MALT淋巴瘤根除Hp后,60%~80%的患者可获得缓解[18],因此根除Hp是局部阶段胃MALT淋巴瘤的一线治疗。有t (11;18) 易位的胃MALT淋巴瘤根除Hp后多数无效,这些患者需要辅助化学治疗和(或)放射治疗[30-31]。所有患者根除Hp后均需密切随访。如根除Hp治疗后胃MALT淋巴瘤无应答或发生进展,则需要化学治疗和(或)放射治疗。

【陈述9】服用阿司匹林或NSAID增加Hp感染患者发生消化性溃疡的风险。

证据质量:高;推荐强度:强;共识水平:100%。

阿司匹林、NSAID和Hp感染是消化性溃疡和溃疡并发症发生的独立危险因素[32]。Meta分析结果显示,服用NSAID可增加Hp感染者发生消化性溃疡风险;服用NSAID前根除Hp可降低溃疡发生的风险[33-35]。服用低剂量阿司匹林是否增加Hp感染者溃疡发生风险的结论不一[34],多数研究结果提示增加溃疡发生风险,长期服用前根除Hp可降低溃疡发生的风险[36-37]。

【陈述10】长期服用PPI会使Hp胃炎分布发生改变,增加胃体胃炎发生的风险,根除Hp可降低这种风险。

证据质量:中;推荐强度:强;共识水平:100%。

Hp胃炎一般表现为胃窦为主胃炎。长期服用PPI者胃酸分泌减少,Hp定植从胃窦向胃体位移,发生胃体胃炎[38],增加胃体黏膜发生萎缩的风险[39]。胃体黏膜萎缩可显著增加胃癌发生风险[2]。根除Hp可降低或消除长期服用PPI者胃体胃炎的发生风险[40]。

【陈述11】有证据显示Hp感染与不明原因的缺铁性贫血、特发性血小板减少性紫癜、维生素B12缺乏症等疾病相关。在这些疾病中,应检测和根除Hp。

证据质量:低;推荐强度:条件;共识水平:100%。

Hp感染与成人和儿童的不明原因缺铁性贫血密切相关,根除Hp可提高血红蛋白水平,在中-重度贫血患者中更为显著,与铁剂联合应用可提高疗效[41-43]。

Hp阳性特发性血小板减少性紫癜患者根除Hp后,约50%的成人和约39%的儿童患者血小板水平可得到提高[44-45],检测和根除Hp已被国际相关共识推荐[46],但美国血液病学会相关指南并不推荐儿童患者常规检测和根除Hp[47]。

有研究显示,Hp感染可能与维生素B12吸收不良相关,但维生素B12缺乏者多与自身免疫相关,根除Hp仅起辅助作用[48]。

【陈述12】Hp胃炎可增加或减少胃酸分泌,根除治疗可逆转或部分逆转这些影响。

证据质量:高;推荐强度:强;共识水平:100%。

Hp胃炎中,胃窦为主的非萎缩性胃炎胃酸分泌常增加,这些患者发生十二指肠溃疡的风险增加;而累及胃体的胃炎尤其是伴有胃黏膜萎缩者胃酸分泌减少,这些患者发生胃癌的风险增加[49]。根除Hp消除了胃炎,可逆转或部分逆转上述胃酸分泌改变[50-51]。伴有下食管括约肌功能不全的胃体胃炎者根除Hp后胃酸恢复性增加,可增加胃食管反流病发生的风险[52]。但这些患者如不根除Hp则发生胃癌的风险增加。“两害相权取其轻”,应根除Hp[1]。

【陈述13】Hp与若干胃十二指肠外疾病呈正相关或负相关,但这些相关的因果关系尚未证实。

证据质量:中;推荐强度:条件;共识水平:90.5%。

除上述胃肠外疾病外,Hp感染还被报道可能与其他若干疾病呈正相关或负相关。呈正相关的疾病包括冠状动脉粥样硬化性心脏病、脑卒中、阿尔茨海默病、帕金森病、肥胖、结肠肿瘤和慢性荨麻疹等[53-58];呈负相关的疾病包括哮喘、食管腺癌和肥胖等[59-61]。但这些报道的相关性并不完全一致,其因果关系尚不明确。

【陈述14】根除Hp可显著改善胃黏膜炎性反应,阻止或延缓胃黏膜萎缩、肠化生的发生和发展,部分逆转萎缩,但难以逆转肠化生。

证据质量:中;推荐强度:强;共识水平:100%。

Hp感染诱发慢性活动性胃炎,根除Hp使胃黏膜活动性炎性反应消退,慢性炎性反应亦可不同程度消退[62]。Hp感染诱发的炎性反应与胃黏膜萎缩和(或)肠化生发生、发展密切相关[63],因此根除Hp可延缓或阻止胃黏膜萎缩和(或)肠化生发生、发展[64-65]。根除Hp可使部分患者的胃黏膜萎缩逆转[66],但肠化生似乎难以逆转[66-67]。

二、Hp感染的诊断

【陈述1】临床应用的非侵入性Hp检测试验中,尿素呼气试验是最受推荐的方法,单克隆粪便抗原试验可作为备选,血清学试验限于一些特定情况(消化性溃疡出血、胃MALT淋巴瘤和严重胃黏膜萎缩)。

证据质量:中;推荐强度:条件;共识水平:100%。

非侵入性Hp检测试验包括尿素呼气试验、粪便抗原试验和血清学试验。尿素呼气试验包括13C-尿素呼气试验和14C-尿素呼气试验,是临床最常应用的非侵入性试验,具有Hp检测准确性相对较高,操作方便和不受Hp在胃内灶性分布影响等优点[68-69]。但当检测值接近临界值(cut-off value)时,结果并不可靠[70],可间隔一段时间后再次检测或用其他方法检测。胃部分切除术后患者用该方法检测Hp准确性显著下降[71],可采用快速尿素酶试验和(或)组织学方法检测。

基于单克隆抗体的粪便抗原试验检测Hp准确性与尿素呼气试验相似[72-73],在尿素呼气试验配合欠佳人员(儿童等)检测中具有优势。

常规的血清学试验检测Hp抗体IgG,其阳性不一定是现症感染,不能用于根除治疗后复查[69,73],因此其临床应用受限。消化性溃疡出血、胃MALT淋巴瘤和胃黏膜严重萎缩等疾病患者存在Hp检测干扰因素或胃黏膜Hp菌量少,此时用其他方法检测可能会导致假阴性[4],而血清学试验则不受这些因素影响[69,73],阳性可视为现症感染。

【陈述2】若患者无活组织检查(以下简称活检)禁忌,胃镜检查如需活检,推荐快速尿素酶试验作为Hp检测方法。最好从胃窦和胃体各取1块活检。不推荐快速尿素酶试验作为根除治疗后的评估试验。

证据质量:中;推荐强度:条件;共识水平:100%。

快速尿素酶试验具有快速、简便和准确性相对较高的优点[74],完成胃镜检查后不久就能得出Hp检测结果,阳性者即可行根除治疗。Hp在胃内呈灶性分布,多点活检可提高检测准确性[69,73]。根除治疗后Hp密度降低,在胃内分布发生改变,易造成检测结果假阴性,因此不推荐用于根除治疗后Hp状态的评估[4]。

【陈述3】因消化不良症状行胃镜检查无明显胃黏膜病变者也应行Hp检测,因为这些患者也可能有Hp感染。

证据质量:中;推荐强度:强;共识水平:100%。

京都共识推荐,根除Hp是Hp阳性消化不良患者的一线治疗[2]。这一推荐的主要依据是部分有消化不良症状的Hp胃炎患者根除Hp后症状可获得长期缓解。慢性胃炎常规内镜诊断与组织学诊断符合率不高,诊断主要依据组织学检查[75]。内镜检查观察胃黏膜未发现黏膜可见病变(visible lesions)者不能排除存在Hp胃炎[76]。美国胃肠病学会提出,这一情况下如果Hp状态未知,推荐常规活检行Hp检测[77]。

【陈述4】多数情况下,有经验的病理医师行胃黏膜常规染色(HE染色)即可作出Hp感染诊断。存在慢性活动性胃炎而组织学检查未发现Hp时,可行特殊染色检查。

证据质量:中;推荐强度:条件;共识水平:100%。

慢性胃炎组织学诊断和分类的“悉尼系统(Sydney system)”包含了Hp这项观察指标,这一系统要求取5块组织(胃窦2块、胃角1块和胃体2块)行胃黏膜活检[75,78-79]。基于这一标准,有经验的病理医师行胃黏膜常规染色(HE染色)即可作出有无Hp感染的诊断[80]。活动性炎性反应的存在高度提示Hp感染,如常规组织学染色未发现Hp,可行特殊染色检查[80],包括Giemsa染色、Warthin-Starry银染色或免疫组化染色等[80-81],也可酌情行尿素呼气试验。

【陈述5】如准备行Hp药物敏感试验,可采用培养或分子生物学方法检测。

证据质量:中;推荐强度:强;共识水平:95.2%。

培养诊断Hp感染特异性高,培养出的Hp菌株可用于药物敏感试验和细菌学研究。但培养有一定技术要求,敏感性偏低,因此不推荐单纯用于Hp感染的常规诊断[69,73]。随着分子生物学技术的发展,用该技术检测Hp耐药基因突变预测耐药的方法已具有临床实用价值[82]。

【陈述6】随着内镜新技术的发展,内镜下观察Hp感染征象已成为可能。但这些方法需要相应设备,检查医师需接受相关培训,其准确性和特异性也存在较大差异,因此目前不推荐常规应用。

证据质量:低;推荐强度:强;共识水平:100%。

常规内镜观察到的结节状胃炎(nodular gastritis)被认为高度提示Hp感染;放大内镜和窄带成像技术可观察到一些Hp感染的特殊征像,包括胃小凹和(或)汇集小静脉、上皮下毛细血管网等改变[83-84]。但这些方法的应用需要相应设备,判断需要经验,报道的敏感性和特异性也有较大差异,因此目前不推荐常规应用[69]。

【陈述7】除血清学和分子生物学检测外,Hp检测前必须停用PPI至少 2周,停用抗菌药物、铋剂和某些具有抗菌作用的中药至少 4周。

证据质量:低;推荐强度:条件;共识水平:100%。

抗菌药物、铋剂和某些具有抗菌作用的中药可抑制Hp生长,降低其活性。PPI抑制胃酸分泌,显著提高胃内pH值,从而抑制Hp尿素酶活性。Hp检测前服用这些药物可显著影响基于尿素酶活性(快速尿素酶试验、尿素呼气试验)试验的Hp检出,造成假阴性[4,69]。H2受体拮抗剂对检测结果有轻微影响,抗酸剂则无影响[4]。血清学试验检测Hp抗体和分子生物学方法检测Hp基因不受应用这些药物的影响。

【陈述8】Hp根除治疗后,应常规评估其是否根除。

证据质量:中;推荐强度:强;共识水平:100%。

鉴于目前Hp根除率正处下降趋势,以及未根除者仍存在发生严重疾病的风险,因此推荐所有患者均应在根除治疗后行Hp复查[2]。

【陈述9】评估根除治疗后结果的最佳方法是尿素呼气试验,粪便抗原试验可作为备选。评估应在治疗完成后不少于4周进行。

证据质量:高;推荐强度:强;共识水平:100%。

多数患者根除治疗后无需复查胃镜,可采用非侵入性方法检测Hp,尿素呼气试验是其中的最佳选择[69,73]。评估应在根除治疗结束后4~8周进行,此期间服用抗菌药物、铋剂和某些具有抗菌作用的中药或PPI均会影响检测结果。

三、Hp的根除治疗

【陈述1】Hp对克拉霉素、甲硝唑和左氧氟沙星的耐药率(包括多重耐药率)呈上升趋势,耐药率有一定的地区差异。

证据质量:中;推荐强度:强;共识水平:100%。

我国根除Hp的抗菌药物耐药率未纳入相关权威机构的系统监测,因此其耐药率的资料主要来自各项研究报道。Hp耐药可分原发耐药(primary resistance)和继发耐药(second resistance),后者指治疗失败后耐药。我国Hp对克拉霉素、甲硝唑和左氧氟沙星(氟喹诺酮类)的耐药率呈上升趋势[85],近年报道的Hp原发耐药率克拉霉素为20%~50%,甲硝唑为40%~70%,左氧氟沙星为20%~50%[85-92]。Hp可对这些抗菌药物发生二重、三重或更多重耐药[85-87],报道的克拉霉素和甲硝唑双重耐药率>25%[88-90]。总体上,这些抗菌药物的耐药率已很高,但存在一定的地区差异[92-93]。

【陈述2】目前Hp对阿莫西林、四环素和呋喃唑酮的耐药率仍很低。

证据质量:中;推荐强度:强;共识水平:100%。

与上述3种抗菌药物高耐药率相反,目前我国Hp对阿莫西林(0%~5%)、四环素(0%~5%)和呋喃唑酮(0%~1%)的耐药率仍很低[85-86,94-95]。目前应用这些抗菌药物根除Hp尚无需顾虑是否耐药。这些抗菌药物应用后不容易产生耐药,因此治疗失败后仍可应用。

【陈述3】Hp对克拉霉素和甲硝唑双重耐药率>15%的地区,经验治疗不推荐含克拉霉素和甲硝唑的非铋剂四联疗法。

证据质量:高;推荐强度:强;共识水平:100%。

随着克拉霉素三联疗法根除率下降,Hp Maastricht-4共识已推荐用非铋剂四联方案(PPI+阿莫西林+克拉霉素+甲硝唑)替代前者[96]。非铋剂四联方案根据其给药方法不同分为序贯疗法(前5 d或7 d口服PPI+阿莫西林,后5 d或7 d口服PPI+克拉霉素+甲硝唑)、伴同疗法(10 d或14 d 同时服用4种药物)和混合疗法(前5 d或7 d与序贯疗法相同,后5 d或7 d与伴同疗法相同)。这3种疗法中,伴同疗法服用药物数量最多,相对疗效最高[97]。克拉霉素或甲硝唑单一耐药即可降低序贯疗法疗效[88],该方案在成人中的应用已被摒弃[3-4]。当克拉霉素和甲硝唑双重耐药时,该四联疗法事实上成了PPI+阿莫西林两联疗法,降低伴同疗法根除率[89,97]。当克拉霉素和甲硝唑双重耐药率>15%时,伴同疗法也难以获得高根除率,故Maastricht-5共识不予推荐[4]。我国报道的克拉霉素和甲硝唑双重耐药率已超过这一阈值[88-90]。

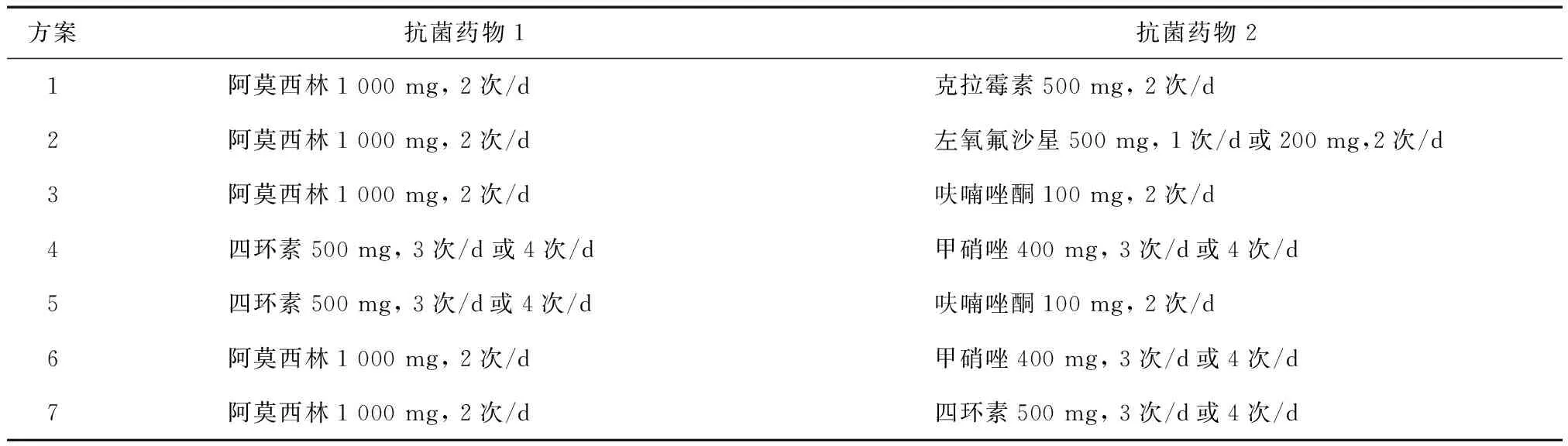

【陈述4】目前推荐铋剂四联(PPI+铋剂+2种抗菌药物)作为主要的经验治疗根除Hp方案(推荐7种方案)。

证据质量:低;推荐强度:强;共识水平:100%。

经典铋剂四联方案由PPI+铋剂+四环素+甲硝唑组成,这一方案确立于1995年[98],先于1996年确立的标准克拉霉素三联方案[99]。由于后者疗效高、服用药物少和不良反应率低,因此很快就替代前者作为一线方案[100]。随着克拉霉素耐药率上升,后者疗效不断下降[101-102],前者重新受到重视[96]。目前已有将铋剂、四环素和甲硝唑置于同一胶囊中的新型制剂(Pylera),在全球推广应用[97]。

我国的相关研究拓展了铋剂四联方案[94,103-106],在第四次全国Hp感染处理共识报告中已推荐了包括经典铋剂四联方案在内的5种方案[107]。此后,我国的研究又拓展了2种铋剂四联方案(PPI+铋剂+阿莫西林+甲硝唑,PPI+铋剂+阿莫西林+四环素)[91,94,108]。这些方案的组成、药物剂量和用法见表2。这些方案的根除率均可达到85%~94%,绝大多数研究采用14 d疗程,含甲硝唑方案中的甲硝唑剂量为1 600 mg/d[91,94-95,103-106]。我国拓展的部分铋剂四联方案疗效已被国外研究验证[109-111],被Maastricht-5共识和多伦多共识推荐[3-4],统称为含铋剂的其他抗菌药物组合。

在克拉霉素、左氧氟沙星和甲硝唑高耐药率情况下,14 d 三联疗法(PPI+阿莫西林+克拉霉素, PPI+阿莫西林+左氧氟沙星,PPI+阿莫西林+甲硝唑)加入铋剂仍能提高根除率[91,103-104]。铋剂的主要作用是对Hp耐药菌株额外地增加30%~40%的根除率[112]。

尽管非铋剂四联方案的伴同疗法仍有可能获得与铋剂四联方案接近或相似的根除率。但与前者相比,选择后者有下列优势:铋剂不耐药[112],铋剂短期应用安全性高[113],治疗失败后抗菌药物选择余地大。因此,除非有铋剂禁忌或已知属于低耐药率地区,经验治疗根除Hp应尽可能应用铋剂四联方案。

某些中药或中成药可能有抗Hp的作用,但确切疗效和如何组合根除方案,尚待更多研究验证。

【陈述5】除含左氧氟沙星的方案不作为初次治疗方案外,根除方案不分一线、二线,应尽可能将疗效高的方案用于初次治疗。初次治疗失败后,可在其余方案中选择一种方案进行补救治疗。 方案的选择需根据当地的Hp抗菌药物耐药率和个人药物使用史,权衡疗效、药物费用、不良反应和药物可获得性。

证据质量:中;推荐强度:强;共识水平:100%。

表2 推荐的Hp根除四联方案中抗菌药物组合、剂量和用法a

注:a标准剂量(PPI+铋剂)(2次/d,餐前半小时口服)+ 2种抗菌药物(餐后口服)。标准剂量PPI为艾司奥美拉唑20 mg、雷贝拉唑10 mg(或20 mg)、奥美拉唑20 mg、兰索拉唑30 mg、泮托拉唑40 mg、艾普拉唑 5 mg,以上选一;标准剂量铋剂为枸橼酸铋钾 220 mg(果胶铋标准剂量待确定)

经验治疗推荐了7种铋剂四联方案,除含左氧氟沙星的方案外(作为补救治疗备选),方案不分一线和二线。所有方案中均含有PPI和铋剂,因此选择方案就是选择抗菌药物组合。

根除方案中抗菌药物组合的选择应参考当地人群中监测的Hp耐药率和个人抗菌药物使用史[4,114]。无论是用于其他疾病或根除Hp治疗,对曾经使用过克拉霉素、喹诺酮类药物和甲硝唑者,其感染的Hp有潜在的耐药可能。此外,方案的选择应该权衡疗效、费用、潜在不良反应和药物可获得性,做出个体化抉择。

【陈述6】含左氧氟沙星的方案不推荐用于初次治疗,可作为补救治疗的备选方案。

证据质量:很低;推荐强度:强;共识水平:95.2%。

左氧氟沙星属氟喹诺酮类药物,与其他喹诺酮类药物有交叉耐药。喹诺酮类药物在临床应用甚广,不少患者在根除Hp前就很可能已用过这类药物。目前我国Hp左氧氟沙星耐药率已达20%~50%[85-86]。尽管左氧氟沙星三联方案联合铋剂可在一定程度上克服其耐药[104],但高耐药率势必降低其根除率。为了尽可能提高初次治疗根除率,借鉴国际共识不推荐含左氧氟沙星方案用于初次治疗[3-4]。

【陈述7】补救方案的选择应参考以前用过的方案,原则上不重复原方案。如方案中已应用克拉霉素或左氧氟沙星则应避免再次使用。

证据质量:低;推荐强度:强;共识水平:100%。

经验治疗推荐7种铋剂四联方案,初次治疗可选择6种方案(不选含左氧氟沙星方案);初次治疗失败后,补救治疗避免选择已用过的方案,可选含左氧氟沙星方案,因此仍有6种方案可供选择。克拉霉素和左氧氟沙星应避免重复使用[4,97]。本共识推荐的含克拉霉素或左氧氟沙星方案无重复;但含甲硝唑的方案有2种,会有重复应用可能。重复应用甲硝唑需优化剂量[3](甲硝唑增加至1 600 mg/d), 如初次治疗已用了优化剂量,则不应再次使用。上述方案选择原则也适用于第二次补救治疗。

【陈述8】推荐经验性铋剂四联治疗方案疗程为10 d或14 d。

证据质量:低;推荐强度:强;共识水平:100%。

本共识推荐的7种经验治疗方案的临床试验均采用了14 d疗程,根除率>90%[91,94-95,103-104],因此尽可能将疗程延长至14 d应该是合适的选择。但鉴于我国Hp耐药率有可能存在显著的地区差异,如果能够证实当地某些方案10 d疗程的根除率接近或达到90%,则仍可选择10 d疗程。

【陈述9】不论初次治疗或补救治疗,如需选择含克拉霉素、甲硝唑或左氧氟沙星的三联方案,应进行药物敏感试验。

证据质量:低;推荐强度:强;共识水平:95.2%。

Hp对抗菌药物耐药率上升是其根除率下降的主要原因。耐药对根除率影响较大的是3种三联疗法(PPI+阿莫西林+克拉霉素,PPI+阿莫西林+左氧氟沙星,PPI+阿莫西林+甲硝唑)。目前我国Hp对阿莫西林耐药率很低,可基本忽略,但对克拉霉素、左氧氟沙星和甲硝唑的耐药率已很高。用上述3种方案,敏感菌株感染者14 d疗程的根除率>95%,而耐药菌株感染者的根除率仅为20%~40%[97]。因此在高耐药率地区(如克拉霉素耐药率>15%[4],左氧氟沙星耐药率>10%[115])应用上述方案前行克拉霉素、左氧氟沙星和甲硝唑3种药物的药物敏感试验具有相对优势[116-117]。

然而,目前采用以下策略的经验治疗也能获得高根除率:①选择低耐药率抗菌药物(阿莫西林、四环素和呋喃唑酮)组成的方案;②上述3种三联方案中加上铋剂,可将耐药菌株的根除率额外提高30%~40%[112];③优化甲硝唑剂量[3]。

与经验治疗四联方案相比,基于药物敏感试验的三联方案应用药物数量少,不良反应可能会降低。但药物敏感试验增加了费用,其准确性和可获得性也是影响其推广的因素。因此药物敏感试验在根除Hp治疗中的成本-效益比尚需行进一步评估,其适用于一线、二线还是三线治疗仍有争议[4,117-120]。

【陈述10】抑酸剂在根除方案中起重要作用,选择作用稳定、疗效高、受CYP2C19基因多态性影响较小的PPI,可提高根除率。

证据质量:低;推荐强度:条件;共识水平:100%。

目前推荐的根除Hp方案均含有PPI[3-4]。PPI在根除Hp治疗中的主要作用是抑制胃酸分泌、提高胃内pH值从而增强抗菌药物的作用,包括降低最小抑菌浓度、增加抗菌药物化学稳定性和提高胃液内抗菌药物浓度[121-122]。PPI的抑酸作用受药物作用强度、宿主参与PPI代谢的CYP2C19基因多态性等因素影响[123-125]。选择作用稳定、疗效高、受CYP2C19基因多态性影响较小的PPI,可提高Hp根除率[93,126-127]。新的钾离子竞争性酸阻滞剂(potassium-competitive acid blocker) Vonoprazan抑酸分泌作用更强,其应用有望进一步提高Hp根除率[128]。

【陈述11】青霉素过敏者推荐的铋剂四联方案抗菌药物组合为: ①四环素+甲硝唑;②四环素+呋喃唑酮;③四环素+左氧氟沙星;④克拉霉素+呋喃唑酮;⑤克拉霉素+甲硝唑;⑥克拉霉素+左氧氟沙星。

证据质量:低;推荐强度:条件;共识水平:100%。

在推荐的7种铋剂四联方案中,5种方案抗菌药物组合中含有阿莫西林。阿莫西林抗Hp作用强,不易产生耐药,不过敏者不良反应发生率低,是根除Hp治疗的首选抗菌药物。青霉素过敏者可用耐药率低的四环素替代阿莫西林。四环素与甲硝唑或呋喃唑酮的组合方案已得到推荐[1],与左氧氟沙星的组合也被证实有效[129]。难以获得四环素或四环素有禁忌时,可选择其他抗菌药物组合方案,包括克拉霉素+呋喃唑酮[130]、克拉霉素+甲硝唑[131]和克拉霉素+左氧氟沙星[132]。注意方案⑤和⑥组合的2种抗菌药物Hp耐药率已很高,如果选用,应尽可能将疗程延长至14 d。

四、Hp感染与胃癌

【陈述1】目前认为Hp感染是预防胃癌最重要的可控危险因素。

证据质量:高;推荐强度:强;共识水平:95.2%。

早在1994年世界卫生组织(WHO)下属的国际癌症研究机构(International Agency for Research on Cancer, IARC)就将Hp定为胃癌的Ⅰ类致癌原。大量研究证据显示,肠型胃癌(占胃癌大多数)的发生是Hp感染、环境因素和遗传因素共同作用的结果[133-135]。据估计,约90%非贲门部胃癌的发生与Hp感染相关[135-136];环境因素在胃癌发生中的总体作用次于Hp感染;遗传因素在约1%~3%的遗传性弥漫性胃癌发生中起决定作用[137]。因此Hp感染是目前预防胃癌最重要且可控的危险因素,根除Hp应成为胃癌的一级预防措施[2,4,134]。

【陈述2】胃黏膜萎缩和(或)肠化生发生前实施Hp根除治疗可更有效地降低胃癌发生风险。

证据质量:中;推荐强度:强;共识水平:100%。

根除Hp可改善胃黏膜炎性反应,阻止或延缓胃黏膜萎缩、肠化生的发生和发展,部分逆转萎缩,但难以逆转肠化生[62-67]。在胃黏膜萎缩和(或)肠化生发生前根除Hp,消除了炎性反应,胃黏膜不再发生萎缩和(或)肠化生,阻断了Correa模式“肠型胃癌演变”的进程,几乎可完全消除肠型胃癌发生的风险[138-139]。已发生胃黏膜萎缩和(或)肠化生者根除Hp可延缓胃黏膜萎缩、肠化生发展,也可不同程度地降低胃癌发生风险[140-141]。

【陈述3】血清胃蛋白酶原和Hp抗体联合检测可用于筛查有胃黏膜萎缩的胃癌高风险人群。

证据质量:低;推荐强度:强;共识水平:95.2%。

包括胃蛋白酶原(Ⅰ和Ⅱ)、Hp抗体和胃泌素-17在内的一组血清学试验已被证实可筛查胃黏膜萎缩,包括胃窦或胃体黏膜萎缩[142-143],被称为“血清学活检”(serological biopsy)[4,143]。胃黏膜萎缩特别是胃体黏膜萎缩者是胃癌发生高危人群,非侵入性血清学筛查与内镜检查结合,有助于提高胃癌预防水平[144]。

【陈述4】根除Hp预防胃癌在胃癌高发区人群中有成本-效益比优势。

证据质量:中;推荐强度:强;共识水平:100%。

【陈述5】在胃癌高发区人群中,推荐Hp“筛查和治疗”策略。

证据质量:中;推荐强度:强;共识水平:95.2%。

【陈述6】推荐在胃癌高风险个体筛查和根除Hp。

证据质量:中;推荐强度:强;共识水平:100%。

【陈述7】根除Hp后有胃黏膜萎缩和(或)肠化生者需要随访。

证据质量:低;推荐强度:强;共识水平:100%。

根除Hp不仅可降低胃癌发生风险,也可有效预防消化性溃疡[145]和Hp相关消化不良。相关资料分析显示,在亚洲胃癌高发国家,实施根除Hp预防胃癌策略具有成本-效益比优势[135,146]。我国内镜检查和Hp检测费用均较低;多数根除Hp的药物价格低廉;早期胃癌检出率低[147],晚期胃癌预后差;根除Hp是短期治疗,但预防Hp相关疾病可获得长期效果。因此,在我国胃癌高发区实施根除Hp预防胃癌策略具有成本-效益比优势。

鉴于根除Hp预防胃癌在胃癌高发区人群中有成本-效益比优势,因此推荐在胃癌高发区实施Hp “筛查和治疗”策略。这一策略应与内镜筛查策略相结合,以便提高早期胃癌检出率和发现需要随访的胃癌高风险个体[144,146]。

除在胃癌高发区实施根除Hp“筛查和治疗”策略外,也有必要在胃癌高风险个体中实施这一策略。早期胃癌内镜下切除术后、有胃癌家族史、已证实有胃黏膜萎缩和(或)肠化生或来自胃癌高发区等均属于胃癌高风险个体。

在胃黏膜发生萎缩和(或)肠化生前根除Hp几乎可完全预防肠型胃癌发生,但已发生胃黏膜萎缩和(或)肠化生时根除Hp就不足以完全消除这一风险[148-149],因此需要对这些个体进行随访。慢性胃炎OLGA(Operative Link for Gastritis Assessment)或OLGIM(Operative Link for Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia Assessment)分期系统有助于预测胃癌发生风险[2,150-151],Ⅲ期和Ⅳ期的高风险个体需要定期内镜随访[152-153]。

【陈述8】应提高公众预防胃癌的知晓度。

证据质量:低;推荐强度:强;共识水平:100%。

让公众知晓胃癌的危害和预防胃癌的相关知识,有助于推动胃癌预防。公众需要知晓的是:我国是胃癌高发国家[154];我国发现的胃癌多数处于晚期,预后差,早期发现、治疗的预后好[147];早期胃癌无症状或症状缺乏特异性,内镜检查是早期发现胃癌的主要方法;根除Hp可降低胃癌发生率,尤其是早期根除;有胃癌家族史者是胃癌发生高风险个体;纠正不良环境因素(高盐、吸烟等)和增加新鲜蔬菜、水果摄入也很重要[155-156]。

【陈述9】有效的Hp疫苗将是预防感染的最佳措施。

证据质量:低;推荐强度:强;共识水平:100%。

Hp胃炎作为一种感染性疾病,用有效疫苗预防感染无疑是最佳选择[3,152]。但有效的Hp疫苗研制并不容易,直至最近才看到了疫苗预防Hp感染的曙光[157]。

五、特殊人群Hp感染

【陈述1】不推荐对14岁以下儿童行常规检测Hp。推荐对消化性溃疡儿童行Hp检测和治疗,因消化不良行内镜检查的儿童建议行Hp检测和治疗。

证据质量:低;推荐强度:强;共识水平:100%。

与成人相比,儿童Hp感染者发生严重疾病包括消化性溃疡、萎缩性胃炎和胃癌等疾病的风险低[158];但根除治疗不利因素较多,包括抗菌药物选择余地小(仅推荐阿莫西林、克拉霉素和甲硝唑)[159]和对药物不良反应耐受性低。此外,儿童Hp感染有一定自发清除率[160],根除后再感染率也可能高于成人[161-162]。因此不推荐对14岁以下儿童常规检测Hp。

消化性溃疡根除Hp获益大,有消化性溃疡的儿童推荐行Hp检测和治疗;根除Hp可能对部分消化不良儿童的症状有效,已接受内镜检查的儿童建议行Hp检测和治疗[163]。

【陈述2】老年人(年龄>70岁)根除Hp治疗药物不良反应风险增加,因此对老年人根除Hp治疗应进行获益-风险综合评估,个体化处理。

证据质量:低;推荐强度:强;共识水平:100%。

目前国际上缺乏老年人Hp感染处理共识。问卷调查显示,多数临床医师对老年人根除Hp治疗的态度趋向保守[164]。一般而言,老年人对根除Hp治疗药物的耐受性和依从性降低[165],发生抗菌药物不良反应的风险增加[166];另一方面,非萎缩性胃炎或轻度萎缩性胃炎患者根除Hp预防胃癌的潜在获益下降。老年人中相对突出的服用阿司匹林/NSAID和维生素B12吸收不良等已列入成人Hp根除指征[4]。老年人身体状况不一,根除Hp获益各异,因此对老年人Hp感染应进行获益-风险综合评估,个体化处理。

六、Hp感染与胃肠道微生态

【陈述1】Hp根除治疗可短期影响肠道菌群,其远期影响尚不明确。

证据质量:低;推荐强度:条件;共识水平:95.2%。

目前推荐的根除Hp治疗方案中至少包含2种抗菌药物,抗菌药物的应用会使肠道菌群发生短期改变[167-168],但其长期影响尚不清楚。对一些胃肠道微生物群不成熟(幼童)或不稳定者(老年人、免疫缺陷者等)根除Hp抗菌药物应用需谨慎[167,169]。必要时可在根除Hp治疗同时或根除治疗后补充微生态制剂,以降低抗菌药物对肠道微生态的不良影响[170-171]。

【陈述2】某些益生菌可在一定程度上降低Hp根除治疗引起的胃肠道不良反应。

证据质量:中;推荐强度:强;共识水平:95.2%。

【陈述3】益生菌是否可提高Hp根除率尚有待更多研究证实。

证据质量:低;推荐强度:条件;共识水平:100%。

益生菌种类多,应用剂量不一,与根除Hp治疗联合的用药方法也未统一(根除治疗前、后或同时服用)。目前益生菌在根除Hp治疗中的辅助作用尚有争议,相关meta分析得出的结论不同[172-173],共识报告也有不同观点[3-4]。某些益生菌可减轻根除Hp治疗时胃肠道不良反应少有争议,但是否可提高Hp根除率则尚需更多设计良好的研究证实[174-175]。

参与表决的专家(按姓氏汉语拼音排序):陈旻湖(中山大学附属第一医院消化科);陈烨(南方医科大学南方医院消化科);成虹(北京大学第一医院消化科);杜勤(浙江大学医学院附属第二医院消化科);杜奕奇(上海长海医院消化科);房静远(上海交通大学医学院附属仁济医院消化科);兰春慧(第三军医大学大坪医院消化科);李岩(中国医科大学附属盛京医院消化科);刘文忠(上海交通大学医学院附属仁济医院消化科);陆红(上海交通大学医学院附属仁济医院消化科);吕农华(南昌大学第一附属医院消化科);王江滨(吉林大学中日联谊医院消化科);王学红(青海大学附属医院消化科);谢勇(南昌大学第一附属医院消化科);许建明(安徽医科大学第一附属医院消化科);徐三平(华中科技大学同济医学院附属协和医院消化科);杨云生(解放军总医院消化科);曾志荣(中山大学附属第一医院消化科);张建中(中国疾病预防控制中心传染病预防控制所);郑鹏远(郑州大学第二附属医院消化科);周丽雅(北京大学第三医院消化科)

1 中华医学会消化病学分会幽门螺杆菌学组/全国幽门螺杆菌研究协作组; 刘文忠, 谢勇, 成虹, 等. 第四次全国幽门螺杆菌感染处理共识报告[J]. 胃肠病学, 2012, 17 (10): 618-625.

2 Sugano K, Tack J, Kuipers EJ, et al; faculty members of Kyoto Global Consensus Conference. Kyoto global consensus report onHelicobacterpylorigastritis[J]. Gut, 2015, 64 (9): 1353-1367.

3 Fallone CA, Chiba N, van Zanten SV, et al. The Toronto Consensus for the Treatment ofHelicobacterpyloriInfection in Adults[J]. Gastroenterology, 2016, 151 (1): 51-69.

4 Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, et al; European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study Group and Consensus panel. Management ofHelicobacterpyloriinfection-the Maastricht Ⅴ/Florence Consensus Report[J]. Gut, 2017, 66 (1): 6-30.

5 中华医学会消化病学分会幽门螺杆菌学组. 幽门螺杆菌胃炎京都全球共识研讨会纪要[J]. 中华消化杂志, 2016, 36 (1): 53-57.

6 蒋朱明, 詹思延, 贾晓巍, 等. 制订/修订《临床诊疗指南》的基本方法及程序[J]. 中华医学杂志, 2016, 96 (4): 250-253.

7 Qaseem A, Snow V, Owens DK, et al; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. The development of clinical practice guidelines and guidance statements of the American College of Physicians: summary of methods[J]. Ann Intern Med, 2010, 153 (3): 194-199.

8 Sipponen P. Natural history of gastritis and its relationship to peptic ulcer disease[J]. Digestion, 1992, 51 Suppl 1: 70-75.

9 Moayyedi P, Forman D, Braunholtz D, et al. The proportion of upper gastrointestinal symptoms in the community associated withHelicobacterpylori, lifestyle factors, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Leeds HELP Study Group[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2000, 95 (6): 1448-1455.

10 Sugano K. Screening of gastric cancer in Asia[J]. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol, 2015, 29 (6): 895-905.

11 Sonnenberg A, Lash RH, Genta RM. A national study ofHelicobactorpyloriinfection in gastric biopsy specimens[J]. Gastroenterology, 2010, 139 (6): 1894-1901.

12 Warren JR. Gastric pathology associated withHelicobacterpylori[J]. Gastroenterol Clin North Am, 2000, 29 (3): 705-751.

13 Marshall BJ, Armstrong JA, McGechie DB, et al. Attempt to fulfil Koch’s postulates for pyloric Campylobacter[J]. Med J Aust, 1985, 142 (8): 436-439.

14 Morris A, Nicholson G. Ingestion of Campylobacter pyloridis causes gastritis and raised fasting gastric pH[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 1987, 82 (3): 192-199.

15 Leja M, Axon A, Brenner H. Epidemiology ofHelicobacterpyloriinfection[J]. Helicobacter, 2016, 21 Suppl 1: 3-7.

16 Van der Hulst RW, Tytgat GN.Helicobacterpyloriand peptic ulcer disease[J]. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl, 1996, 220: 10-18.

17 Nakamura S, Sugiyama T, Matsumoto T, et al; JAPAN GAST Study Group. Long-term clinical outcome of gastric MALT lymphoma after eradication ofHelicobacterpylori: a multicentre cohort follow-up study of 420 patients in Japan[J]. Gut, 2012, 61 (4): 507-513.

18 Nagy P, Johansson S, Molloy-Bland M. Systematic review of time trends in the prevalence ofHelicobacterpyloriinfection in China and the USA[J]. Gut Pathog, 2016, 8: 8.

19 Gisbert JP, Calvet X.Helicobacterpylori"Test-and-Treat" Strategy for Management of Dyspepsia: A Comprehensive Review[J]. Clin Transl Gastroenterol, 2013, 4: e32.

20 Ford AC, Qume M, Moayyedi P, et al.Helicobacterpylori“test and treat” or endoscopy for managing dyspepsia: an individual patient data meta-analysis[J]. Gastroenterology, 2005, 128 (7): 1838-1844.

21 刘文忠. 重视根除幽门螺杆菌在消化不良处理中的应用[J]. 中华消化杂志, 2016, 36 (1): 2-4.

22 Chen SL, Gwee KA, Lee JS, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: prompt endoscopy as the initial management strategy for uninvestigated dyspepsia in Asia[J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2015, 41 (3): 239-252.

23 Talley NJ, Vakil NB, Moayyedi P. American gastroenterological association technical review on the evaluation of dyspepsia[J]. Gastroenterology, 2005, 129 (5): 1756-1780.

24 Suzuki H, Moayyedi P.Helicobacterpyloriinfection in functional dyspepsia[J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2013, 10 (3): 168-174.

25 Sugano K. Should we still subcategorizeHelicobacterpylori-associated dyspepsia as functional disease? [J]. J Neurogastroenterol Motil, 2011, 17 (4): 366-371.

26 Stanghellini V, Chan FK, Hasler WL, et al. Gastroduodenal Disorders[J]. Gastroenterology, 2016, 150 (6): 1380-1392.

27 NIH Consensus Conference.Helicobacterpyloriin peptic ulcer disease. NIH Consensus Development Panel onHelicobacterpyloriin Peptic Ulcer Disease[J]. JAMA, 1994, 272 (1): 65-69.

28 Gisbert JP, Calvet X, Cosme A, et al;H.pyloriStudy Group of the Asociación Espaola de Gastroenterología (Spanish Gastroenterology Association). Long-term follow-up of 1,000 patients cured ofHelicobacterpyloriinfection following an episode of peptic ulcer bleeding[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2012, 107 (8): 1197-1204.

29 Enserink M. Physiology or medicine. Triumph of the ulcer-bug theory[J]. Science, 2005, 310 (5745): 34-35.

30 Nakamura S, Matsumoto T. Treatment Strategy for Gastric Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue Lymphoma[J]. Gastroenterol Clin North Am, 2015, 44 (3): 649-660.

31 Fischbach W. Gastric MALT lymphoma - update on diagnosis and treatment[J]. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol, 2014, 28 (6): 1069-1077.

32 Huang JQ, Sridhar S, Hunt RH. Role ofHelicobacterpyloriinfection and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in peptic-ulcer disease: a meta-analysis[J]. Lancet, 2002, 359 (9300): 14-22.

33 Vergara M, Catalán M, Gisbert JP, et al. Meta-analysis: role ofHelicobacterpylorieradication in the prevention of peptic ulcer in NSAID users[J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2005, 21 (12): 1411-1418.

34 Melcarne L, García-Iglesias P, Calvet X. Management of NSAID-associated peptic ulcer disease[J]. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2016, 10 (6): 723-733.

35 Sostres C, Carrera-Lasfuentes P, Benito R, et al. Peptic Ulcer Bleeding Risk. The Role ofHelicobacterpyloriInfection in NSAID/Low-Dose Aspirin Users[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2015, 110 (5): 684-689.

36 Hunt RH, Bazzoli F. Review article: should NSAID/low-dose aspirin takers be tested routinely forH.pyloriinfection and treated if positive? Implications for primary risk of ulcer and ulcer relapse after initial healing[J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2004, 19 Suppl 1: 9-16.

37 Chan FK, Ching JY, Suen BY, et al. Effects ofHelicobacterpyloriinfection on long-term risk of peptic ulcer bleeding in low-dose aspirin users[J]. Gastroenterology, 2013, 144 (3): 528-535.

38 Kuipers EJ, Uyterlinde AM, Pea AS, et al. Increase ofHelicobacterpylori-associated corpus gastritis during acid suppressive therapy: implications for long-term safety[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 1995, 90 (9): 1401-1406.

39 Lundell L, Havu N, Miettinen P, et al; Nordic Gerd Study Group. Changes of gastric mucosal architecture during long-term omeprazole therapy: results of a randomized clinical trial[J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2006, 23 (5): 639-647.

40 Schenk BE, Kuipers EJ, Nelis GF, et al. Effect ofHelicobacterpylorieradication on chronic gastritis during omeprazole therapy[J]. Gut, 2000, 46 (5): 615-621.

41 Yuan W, Li Yumin, Yang Kehu, et al. Iron deficiency anemia inHelicobacterpyloriinfection: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials[J]. Scand J Gastroenterol, 2010, 45 (6): 665-676.

42 Queiroz DM, Harris PR, Sanderson IR, et al. Iron status andHelicobacterpyloriinfection in symptomatic children: an international multi-centered study[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8 (7): e68833.

43 Goddard AF, James MW, McIntyre AS, et al; British Society of Gastroenterology. Guidelines for the management of iron deficiency anaemia[J]. Gut, 2011, 60 (10): 1309-1316.

44 Stasi R, Sarpatwari A, Segal JB, et al. Effects of eradication ofHelicobacterpyloriinfection in patients with immune thrombocytopenic purpura: a systematic review[J]. Blood, 2009, 113 (6): 1231-1240.

45 Russo G, Miraglia V, Branciforte F, et al; AIEOP-ITP Study Group. Effect of eradication ofHelicobacterpyloriin children with chronic immune thrombocytopenia: a prospective, controlled, multicenter study[J]. Pediatr Blood Cancer, 2011, 56 (2): 273-278.

46 Provan D, Stasi R, Newland AC, et al. International consensus report on the investigation and management of primary immune thrombocytopenia[J]. Blood, 2010, 115 (2): 168-186.

47 Neunert C, Lim W, Crowther M, et al; American Society of Hematology. The American Society of Hematology 2011 evidence-based practice guideline for immune thrombocytopenia[J]. Blood, 2011, 117 (16): 4190-4207.

48 Stabler SP. Clinical practice. Vitamin B12deficiency[J]. N Engl J Med, 2013, 368 (2): 149-160.

49 Malfertheiner P. The intriguing relationship ofHelicobacterpyloriinfection and acid secretion in peptic ulcer disease and gastric cancer[J]. Dig Dis, 2011, 29 (5): 459-464.

50 Haruma K, Mihara M, Okamoto E, et al. Eradication ofHelicobacterpyloriincreases gastric acidity in patients with atrophic gastritis of the corpus-evaluation of 24-h pH monitoring[J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 1999, 13 (2): 155-162.

51 Iijima K, Ohara S, Sekine H, et al. Changes in gastric acid secretion assayed by endoscopic gastrin test before and afterHelicobacterpylorieradication[J]. Gut, 2000, 46 (1): 20-26.

52 Kandulski A, Malfertheiner P.Helicobacterpyloriand gastroesophageal reflux disease[J]. Curr Opin Gastroenterol, 2014, 30 (4): 402-407.

53 Franceschi F, Tortora A, Gasbarrini G, et al.Helicobacterpyloriand extragastric diseases[J]. Helicobacter, 2014, 19 Suppl 1: 52-58.

54 Hughes WS. An hypothesis: the dramatic decline in heart attacks in the United States is temporally related to the decline in duodenal ulcer disease andHelicobacterpyloriinfection[J]. Helicobacter, 2014, 19 (3): 239-241.

55 Bu XL, Yao XQ, Jiao SS, et al. A study on the association between infectious burden and Alzheimer’s disease[J]. Eur J Neurol, 2015, 22 (12): 1519-1525.

56 Bu XL, Wang X, Xiang Y, et al. The association between infectious burden and Parkinson’s disease: A case-control study[J]. Parkinsonism Relat Disord, 2015, 21 (8): 877-881.

57 Papastergiou V, Karatapanis S, Georgopoulos SD.Helicobacterpyloriand colorectal neoplasia: Is there a causal link? [J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2016, 22 (2): 649-658.

58 Zhang Y, Du T, Chen X, et al. Association betweenHelicobacterpyloriinfection and overweight or obesity in a Chinese population[J]. J Infect Dev Ctries, 2015, 9 (9): 945-953.

59 Daugule I, Zavoronkova J, Santare D.Helicobacterpyloriand allergy: Update of research[J]. World J Methodol, 2015, 5 (4): 203-211.

60 Rokkas T, Pistiolas D, Sechopoulos P, et al. Relationship betweenHelicobacterpyloriinfection and esophageal neoplasia: a meta-analysis[J]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2007, 5 (12): 1413-1417.

61 Lender N, Talley NJ, Enck P, et al. Review article: Associations betweenHelicobacterpyloriand obesity -- an ecological study[J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2014, 40 (1): 24-31.

62 Hojo M, Miwa H, Ohkusa T, et al. Alteration of histological gastritis after cure ofHelicobacterpyloriinfection[J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2002, 16 (11): 1923-1932.

63 Asaka M, Sugiyama T, Nobuta A, et al. Atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia in Japan: results of a large multicenter study[J]. Helicobacter, 2001, 6 (4): 294-299.

64 Venerito M, Malfertheiner P. Preneoplastic conditions in the stomach: always a point of no return? [J]. Dig Dis, 2015, 33 (1): 5-10.

65 Zhou L, Lin S, Ding S, et al. Relationship ofHelicobacterpylorieradication with gastric cancer and gastric mucosal histological changes: a 10-year follow-up study[J]. Chin Med J (Engl), 2014, 127 (8): 1454-1458.

66 Wang J, Xu L, Shi R, et al. Gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia before and afterHelicobacterpylorieradication: a meta-analysis[J]. Digestion, 2011, 83 (4): 253-260.

67 Liu KS, Wong IO, Leung WK.Helicobacterpyloriassociated gastric intestinal metaplasia: Treatment and surveillance[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2016, 22 (3): 1311-1320.

68 Ferwana M, Abdulmajeed I, Alhajiahmed A, et al. Accuracy of urea breath test inHelicobacterpyloriinfection: meta-analysis[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2015, 21 (4): 1305-1314.

69 Wang YK, Kuo FC, Liu CJ, et al. Diagnosis ofHelicobacterpyloriinfection: Current options and developments[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2015, 21 (40): 11221-11235.

70 Gisbert JP, Pajares JM. Review article:13C-urea breath test in the diagnosis ofHelicobacterpyloriinfection -- a critical review[J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2004, 20 (10): 1001-1017.

71 Tian XY, Zhu H, Zhao J, et al. Diagnostic performance of urea breath test, rapid urea test, and histology forHelicobacterpyloriinfection in patients with partial gastrectomy: a meta-analysis[J]. J Clin Gastroenterol, 2012, 46 (4): 285-292.

72 Gisbert JP, de la Morena F, Abraira V. Accuracy of monoclonal stool antigen test for the diagnosis ofH.pyloriinfection: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2006, 101 (8): 1921-1930.

73 Atkinson NS, Braden B.HelicobacterpyloriInfection: Diagnostic Strategies in Primary Diagnosis and After Therapy[J]. Dig Dis Sci, 2016, 61 (1): 19-24.

74 Uotani T, Graham DY. Diagnosis ofHelicobacterpyloriusing the rapid urease test[J]. Ann Transl Med, 2015, 3 (1): 9.

75 中华医学会消化病学分会; 房静远, 刘文忠, 李兆申,等. 中国慢性胃炎共识意见(2012年,上海)[J]. 中华消化杂志, 2013, 33 (1): 5-16.

76 Lahner E, Esposito G, Zullo A, et al. Gastric precancerous conditions andHelicobacterpyloriinfection in dyspeptic patients with or without endoscopic lesions[J]. Scand J Gastroenterol, 2016, 51 (11): 1294-1298.

77 Yang YX, Brill J, Krishnan P, et al; American Gastroenterological Association Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on the Role of Upper Gastrointestinal Biopsy to Evaluate Dyspepsia in the Adult Patient in the Absence of Visible Mucosal Lesions[J]. Gastroenterology, 2015, 149 (4): 1082-1087.

78 Sipponen P, Price AB. The Sydney System for classification of gastritis 20 years ago[J]. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2011, 26 Suppl 1: 31-34.

79 Lash JG, Genta RM. Adherence to the Sydney System guidelines increases the detection of Helicobacter gastritis and intestinal metaplasia in 400738 sets of gastric biopsies[J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2013, 38 (4): 424-431.

80 Panarelli NC, Ross DS, Bernheim OE, et al. Utility of ancillary stains forHelicobacterpyloriin near-normal gastric biopsies[J]. Hum Pathol, 2015, 46 (3): 397-403.

81 Batts KP, Ketover S, Kakar S, et al; Rodger C Haggitt Gastrointestinal Pathology Society. Appropriate use of special stains for identifyingHelicobacterpylori: Recommendations from the Rodger C. Haggitt Gastrointestinal Pathology Society[J]. Am J Surg Pathol, 2013, 37 (11): e12-e22.

82 Smith SM, O’Morain C, McNamara D. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing forHelicobacterpyloriin times of increasing antibiotic resistance[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2014, 20 (29): 9912-9921.

83 Ji R, Li YQ. DiagnosingHelicobacterpyloriinfectioninvivoby novel endoscopic techniques[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2014, 20 (28): 9314-9320.

84 Qi Q, Guo C, Ji R,et al. Diagnostic Performance of Magnifying Endoscopy forHelicobacterpyloriInfection: A Meta-Analysis[J]. PLoS One, 2016, 11 (12): e0168201.

85 Zhang YX, Zhou LY, Song ZQ, et al. Primary antibiotic resistance ofHelicobacterpyloristrains isolated from patients with dyspeptic symptoms in Beijing: a prospective serial study[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2015, 21 (9): 2786-2792.

86 Su P, Li Y, Li H, et al. Antibiotic resistance ofHelicobacterpyloriisolated in the Southeast Coastal Region of China[J]. Helicobacter, 2013, 18 (4): 274-279.

87 Bai P, Zhou LY, Xiao XM, et al. Susceptibility ofHelicobacterpylorito antibiotics in Chinese patients[J]. J Dig Dis, 2015, 16 (8): 464-470.

88 Zhou L, Zhang J, Chen M, et al. A comparative study of sequential therapy and standard triple therapy forHelicobacterpyloriinfection: a randomized multicenter trial[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2014, 109 (4): 535-541.

89 Zhou L, Zhang J, Song Z, et al. Tailored versus Triple plus Bismuth or Concomitant Therapy as InitialHelicobacterpyloriTreatment: A Randomized Trial[J]. Helicobacter, 2016, 21 (2): 91-99.

90 Song Z, Zhou L, Zhang J, et al. Hybrid Therapy as First-Line Regimen forHelicobacterpyloriEradication in Populations with High Antibiotic Resistance Rates[J]. Helicobacter, 2016, 21 (5): 382-388.

91 Zhang W, Chen Q, Liang X, et al. Bismuth, lansoprazole, amoxicillin and metronidazole or clarithromycin as first-lineHelicobacterpyloritherapy[J]. Gut, 2015, 64 (11): 1715-1720.

92 Xie C, Lu NH. Review: clinical management ofHelicobacterpyloriinfection in China[J]. Helicobacter, 2015, 20 (1): 1-10.

93 Hong J, Shu X, Liu D, et al. Antibiotic resistance and CYP2C19 polymorphisms affect the efficacy of concomitant therapies forHelicobacterpyloriinfection: an open-label, randomized, single-centre clinical trial[J]. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2016, 71 (8): 2280-2285.

94 Liang X, Xu X, Zheng Q, et al. Efficacy of bismuth-containing quadruple therapies for clarithromycin-, metronidazole-, and fluoroquinolone-resistantHelicobacterpyloriinfections in a prospective study[J]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2013, 11 (7): 802-807.

95 Chen Q, Zhang W, Fu Q, et al. Rescue Therapy forHelicobacterpyloriEradication: A Randomized Non-Inferiority Trial of Amoxicillin or Tetracycline in Bismuth Quadruple Therapy[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2016, 111 (12): 1736-1742.

96 Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, et al; European Helicobacter Study Group. Management ofHelicobacterpyloriinfection -- the Maastricht Ⅳ/ Florence Consensus Report[J]. Gut, 2012, 61 (5): 646-664.

97 Graham DY, Dore MP.Helicobacterpyloritherapy: a paradigm shift[J]. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther, 2016, 14 (6): 577-585.

98 Graham DY, Lee SY. How to Effectively Use Bismuth Quadruple Therapy: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly[J]. Gastroenterol Clin North Am, 2015, 44 (3): 537-563.

99 Lind T, Veldhuyzen van Zanten S, Unge P, et al. Eradication ofHelicobacterpyloriusing one-week triple therapies combining omeprazole with two antimicrobials: the MACH Ⅰ Study[J]. Helicobacter, 1996, 1 (3): 138-144.

100Current European concepts in the management ofHelicobacterpyloriinfection. The Maastricht Consensus Report. EuropeanHelicobacterpyloriStudy Group[J]. Gut, 1997, 41 (1): 8-13.

101Graham DY, Fischbach L.Helicobacterpyloritreatment in the era of increasing antibiotic resistance[J]. Gut, 2010, 59 (8): 1143-1153.

102Wang B, Lv ZF, Wang YH, et al. Standard triple therapy forHelicobacterpyloriinfection in China: a meta-analysis[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2014, 20 (40): 14973-14985.

103Sun Q, Liang X, Zheng Q,et al. High efficacy of 14-day triple therapy-based, bismuth-containing quadruple therapy for initialHelicobacterpylorieradication[J]. Helicobacter, 2010, 15 (3): 233-238.

104Liao J, Zheng Q, Liang X, et al. Effect of fluoroquinolone resistance on 14-day levofloxacin triple and triple plus bismuth quadruple therapy[J]. Helicobacter, 2013, 18 (5): 373-377.

105Lu H, Zhang W, Graham DY. Bismuth-containing quadruple therapy forHelicobacterpylori: lessons from China[J]. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2013, 25 (10): 1134-1140.

106Xie Y, Zhu Y, Zhou H, et al. Furazolidone-based triple and quadruple eradication therapy forHelicobacterpyloriinfection[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2014, 20 (32): 11415-11421.

107Chinese Society of Gastroenterology, Chinese Study Group onHelicobacterpylori; Liu WZ, Xie Y, Cheng H, et al. Fourth Chinese National Consensus Report on the management ofHelicobacterpyloriinfection[J]. J Dig Dis, 2013, 14 (5): 211-221.

108Lv ZF, Wang FC, Zheng HL, et al. Meta-analysis: is combination of tetracycline and amoxicillin suitable forHelicobacterpyloriinfection? [J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2015, 21 (8): 2522-2533.

109Gisbert JP, Romano M, Gravina AG, et al.Helicobacterpylorisecond-line rescue therapy with levofloxacin- and bismuth-containing quadruple therapy, after failure of standard triple or non-bismuth quadruple treatments[J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2015, 41 (8): 768-775.

110Ergül B, Dogˇ an Z, Sarikaya M, et al. The efficacy of two-week quadruple first-line therapy with bismuth, lansoprazole, amoxicillin, clarithromycin onHelicobacterpylorieradication: a prospective study[J]. Helicobacter, 2013, 18 (6): 454-458.

111Srinarong C, Siramolpiwat S, Wongcha-um A, et al. Improved eradication rate of standard triple therapy by adding bismuth and probiotic supplement forHelicobacterpyloritreatment in Thailand[J]. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev, 2014, 15 (22): 9909-9913.

112Dore MP, Lu H, Graham DY. Role of bismuth in improvingHelicobacterpylorieradication with triple therapy[J]. Gut, 2016, 65 (5): 870-878.

113Ford AC, Malfertheiner P, Giguere M, et al. Adverse events with bismuth salts forHelicobacterpylorieradication: systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2008, 14 (48): 7361-7370.

114Lim SG, Park RW, Shin SJ, et al. The relationship between the failure to eradicateHelicobacterpyloriand previous antibiotics use[J]. Dig Liver Dis, 2016, 48 (4): 385-390.

115Chen PY, Wu MS, Chen CY, et al; Taiwan Gastrointestinal Disease and Helicobacter Consortium. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the efficacy of levofloxacin triple therapy as the first- or second-line treatments ofHelicobacterpyloriinfection[J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2016, 44 (5): 427-437.

116Cosme A, Lizasoan J, Montes M, et al. Antimicrobial Susceptibility-Guided Therapy Versus Empirical Concomitant Therapy for Eradication ofHelicobacterpyloriin a Region with High Rate of Clarithromycin Resistance[J]. Helicobacter, 2016, 21 (1): 29-34.

117Graham DY, Laine L. The TorontoHelicobacterpyloriConsensus in Context[J]. Gastroenterology, 2016, 151 (1): 9-12.

118López-Góngora S, Puig I, Calvet X, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: susceptibility-guided versus empirical antibiotic treatment forHelicobacterpyloriinfection[J]. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2015, 70 (9): 2447-2455.

119Puig I, López-Góngora S, Calvet X, et al. Systematic review: third-line susceptibility-guided treatment forHelicobacterpyloriinfection[J]. Therap Adv Gastroenterol, 2016, 9 (4): 437-448.

120Chen H, Dang Y, Zhou X, et al. Tailored Therapy Versus Empiric Chosen Treatment forHelicobacterpyloriEradication: A Meta-Analysis[J]. Medicine (Baltimore), 2016, 95 (7): e2750.

121Labenz J. Current role of acid suppressants inHelicobacterpylorieradication therapy[J]. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol, 2001, 15 (3): 413-431.

122Gisbert JP. Potent gastric acid inhibition inHelicobacterpylorieradication[J]. Drugs, 2005, 65 Suppl 1: 83-96.

123Kuo CH, Lu CY, Shih HY, et al. CYP2C19 polymorphism influencesHelicobacterpylorieradication[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2014, 20 (43): 16029-16036.

124Uotani T, Miftahussurur M, Yamaoka Y. Effect of bacterial and host factors onHelicobacterpylorieradication therapy[J]. Expert Opin Ther Targets, 2015, 19 (12): 1637-1650.

125Sahara S, Sugimoto M, Uotani T, et al. Twice-daily dosing of esomeprazole effectively inhibits acid secretion in CYP2C19 rapid metabolisers compared with twice-daily omeprazole, rabeprazole or lansoprazole[J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2013, 38 (9): 1129-1137.

126Anagnostopoulos GK, Tsiakos S, Margantinis G, et al. Esomeprazole versus omeprazole for the eradication ofHelicobacterpyloriinfection: results of a randomized controlled study[J]. J Clin Gastroenterol, 2004, 38 (6): 503-506.

127McNicholl AG, Linares PM, Nyssen OP,et al. Meta-analysis: esomeprazole or rabeprazolevs. first-generation pump inhibitors in the treatment ofHelicobacterpyloriinfection[J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2012, 36 (5): 414-425.

128Akazawa Y, Fukuda D, Fukuda Y. Vonoprazan-based therapy forHelicobacterpylorieradication: experience and clinical evidence[J]. Therap Adv Gastroenterol, 2016, 9 (6): 845-852.

129Hsu PI, Chen WC, Tsay FW, et al; Taiwan Acid-Related Disease (TARD) Study Group. Ten-day Quadruple therapy comprising proton-pump inhibitor, bismuth, tetracycline, and levofloxacin achieves a high eradication rate forHelicobacterpyloriinfection after failure of sequential therapy[J]. Helicobacter, 2014, 19 (1): 74-79.

130刘文忠, 吕宝妹, 萧树东, 等. 含克拉霉素的短程三联疗法根除幽门螺杆菌[J]. 中华内科杂志, 1996, 35 (12): 803-806.

131Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain C, et al. Current concepts in the management ofHelicobacterpyloriinfection: the Maastricht Ⅲ Consensus Report[J]. Gut, 2007, 56 (6): 772-781.

132Assem M, El Azab G, Rasheed MA, et al. Efficacy and safety of Levofloxacin, Clarithromycin and Esomeprazol as first line triple therapy forHelicobacterpylorieradication in Middle East. Prospective, randomized, blind, comparative, multicenter study[J]. Eur J Intern Med, 2010, 21 (4): 310-314.

133Fock KM, Talley N, Moayyedi P, et al; Asia-Pacific Gastric Cancer Consensus Conference. Asia-Pacific consensus guidelines on gastric cancer prevention[J]. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2008, 23 (3): 351-365.

134Shiotani A, Cen P, Graham DY. Eradication of gastric cancer is now both possible and practical[J]. Semin Cancer Biol, 2013, 23 (6 Pt B): 492-501.

135Herrero R, Park JY, Forman D. The fight against gastric cancer - the IARC Working Group report[J]. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol, 2014, 28 (6): 1107-1114.

136Plummer M, de Martel C, Vignat J, et al. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2012: a synthetic analysis[J]. Lancet Glob Health, 2016, 4 (9): e609-e616.

137Tan RY, Ngeow J. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: What the clinician should know[J]. World J Gastrointest Oncol, 2015, 7 (9): 153-160.

138Wong BC, Lam SK, Wong WM, et al; China Gastric Cancer Study Group.Helicobacterpylorieradication to prevent gastric cancer in a high-risk region of China: a randomized controlled trial[J]. JAMA, 2004, 291 (2): 187-194.

139Ford AC, Forman D, Hunt RH, et al.Helicobacterpylorieradication therapy to prevent gastric cancer in healthy asymptomatic infected individuals: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials[J]. BMJ, 2014, 348: g3174.

140Ma JL, Zhang L, Brown LM, et al. Fifteen-year effects ofHelicobacterpylori, garlic, and vitamin treatments on gastric cancer incidence and mortality[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2012, 104 (6): 488-492.

141Li WQ, Ma JL, Zhang L, et al. Effects ofHelicobacterpyloritreatment on gastric cancer incidence and mortality in subgroups[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2014, 106 (7). pii: dju116.

142曹勤, 冉志华, 萧树东. 血清胃蛋白酶原、胃泌素-17和幽门螺杆菌 IgG抗体筛查萎缩性胃炎和胃癌[J]. 胃肠病学, 2006, 11 (7): 388-394.

143Agréus L, Kuipers EJ, Kupcinskas L, et al. Rationale in diagnosis and screening of atrophic gastritis with stomach-specific plasma biomarkers[J]. Scand J Gastroenterol, 2012, 47 (2): 136-147.

144Yamaguchi Y, Nagata Y, Hiratsuka R, et al. Gastric Cancer Screening by Combined Assay for Serum Anti-HelicobacterpyloriIgG Antibody and Serum Pepsinogen Levels -- The ABC Method[J]. Digestion, 2016, 93 (1): 13-18.

145Lee YC, Chen TH, Chiu HM, et al. The benefit of mass eradication ofHelicobacterpyloriinfection: a community-based study of gastric cancer prevention[J]. Gut, 2013, 62 (5): 676-682.

146Ford AC, Forman D, Hunt R, et al.Helicobacterpylorieradication for the prevention of gastric neoplasia[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2015 (7): CD005583.

147中华医学会消化内镜学分会, 中国抗癌协会肿瘤内镜专业委员会. 中国早期胃癌筛查及内镜诊治共识意见[J]. 中华消化杂志, 2014, 34 (7): 433-448.

148Shichijo S, Hirata Y, Niikura R, et al. Histologic intestinal metaplasia and endoscopic atrophy are predictors of gastric cancer development afterHelicobacterpylorieradication[J]. Gastrointest Endosc, 2016, 84 (4): 618-624.

149Rugge M. Gastric Cancer Risk in Patients withHelicobacterpyloriInfection and Following Its Eradication[J]. Gastroenterol Clin North Am, 2015, 44 (3): 609-624.

150Zhou Y, Li HY, Zhang JJ, et al. Operative link on gastritis assessment stage is an appropriate predictor of early gastric cancer[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2016, 22 (13): 3670-3678.

151Rugge M, de Boni M, Pennelli G, et al. Gastritis OLGA-staging and gastric cancer risk: a twelve-year clinico-pathological follow-up study[J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2010, 31 (10): 1104-1111.

152Graham DY.Helicobacterpyloriupdate: gastric cancer, reliable therapy, and possible benefits[J]. Gastroenterology, 2015, 148 (4): 719-731.

153Lage J, Uedo N, Dinis-Ribeiro M, et al. Surveillance of patients with gastric precancerous conditions[J]. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol, 2016, 30 (6): 913-922.

154Forman D, Sierra MS. The current and projected global burden of gastric cancer (IARC Working Group Reports, No.8) [A]//IARCHelicobacterpyloriWorking Group.Helicobacterpylorieradication as a strategy for preventing gastric cancer[R]. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2014: 5-15.

155Kamada T, Haruma K, Ito M, et al. Time Trends inHelicobacterpyloriInfection and Atrophic Gastritis Over 40 Years in Japan[J]. Helicobacter, 2015, 20 (3): 192-198.

156Wang T, Cai H, Sasazuki S, et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption,Helicobacterpyloriantibodies, and gastric cancer risk: A pooled analysis of prospective studies in China, Japan, and Korea[J]. Int J Cancer, 2017, 140 (3): 591-599.

157Zeng M, Mao XH, Li JX, et al. Efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of an oral recombinantHelicobacterpylorivaccine in children in China: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial[J]. Lancet, 2015, 386 (10002): 1457-1464.

158Razavi A, Bagheri N, Azadegan-Dehkordi F, et al. Comparative Immune Response in Children and Adults withH.pyloriInfection[J]. J Immunol Res, 2015, 2015: 315957.

159中华医学会儿科学分会消化学组.儿童幽门螺杆菌感染诊治专家共识[J]. 中华儿科杂志, 2015, 53 (7): 496-498.

160Malaty HM, Graham DY, Wattigney WA, et al. Natural history ofHelicobacterpyloriinfection in childhood: 12-year follow-up cohort study in a biracial community[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 1999, 28 (2): 279-282.

161Sivapalasingam S, Rajasingham A, Macy JT, et al. Recurrence ofHelicobacterpyloriinfection in Bolivian children and adults after a population-based "screen and treat" strategy[J]. Helicobacter, 2014, 19 (5): 343-348.

162Vanderpas J, Bontems P, Miendje Deyi VY, et al. Follow-up ofHelicobacterpyloriinfection in children over two decades (1988-2007): persistence, relapse and acquisition rates[J]. Epidemiol Infect, 2014, 142 (4): 767-775.

163Koletzko S, Jones NL, Goodman KJ,et al;HpyloriWorking Groups of ESPGHAN and NASPGHAN. Evidence-based guidelines from ESPGHAN and NASPGHAN forHelicobacterpyloriinfection in children[J]. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, 2011, 53 (2): 230-243.

164Matsuzaki J, Hayashi R, Arakawa T, et al; IGICS (The International Gastroenterology Consensus Symposium) Study Group. Questionnaire-Based Survey on Diagnostic and Therapeutic Endoscopies andH.pyloriEradication for Elderly Patients in East Asian Countries[J]. Digestion, 2016, 93 (1): 93-102.

165Salles N, Mégraud F. Current management ofHelicobacterpyloriinfections in the elderly[J]. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther, 2007, 5 (5): 845-856.

166Pea F. Antimicrobial treatment of bacterial infections in frail elderly patients: the difficult balance between efficacy, safety and tolerability[J]. Curr Opin Pharmacol, 2015, 24: 18-22.

167Yap TW, Gan HM, Lee YP, et al.HelicobacterpyloriEradication Causes Perturbation of the Human Gut Microbiome in Young Adults[J]. PLoS One, 2016, 11 (3): e0151893.

168Ladirat SE, Schols HA, Nauta A, et al. High-throughput analysis of the impact of antibiotics on the human intestinal microbiota composition[J]. J Microbiol Methods, 2013, 92 (3): 387-397.

169Blaser MJ. Antibiotic use and its consequences for the normal microbiome[J]. Science, 2016, 352 (6285): 544-545.

170Imase K, Takahashi M, Tanaka A, et al. Efficacy ofClostridiumbutyricumpreparation concomitantly withHelicobacterpylorieradication therapy in relation to changes in the intestinal microbiota[J]. Microbiol Immunol, 2008, 52 (3): 156-161.

171Oh B, Kim JW, Kim BS. Changes in the Functional Potential of the Gut Microbiome Following Probiotic Supplementation duringHelicobacterpyloriTreatment[J]. Helicobacter, 2016, 21 (6): 493-503.

172Zhang MM, Qian W, Qin YY, et al. Probiotics inHelicobacterpylorieradication therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2015, 21 (14): 4345-4357.

173Lu C, Sang J, He H, et al. Probiotic supplementation does not improve eradication rate ofHelicobacterpyloriinfection compared to placebo based on standard therapy: a meta-analysis[J]. Sci Rep, 2016, 6: 23522.

174Goli YD, Moniri R. Efficacy of probiotics as an adjuvant agent in eradication ofHelicobacterpyloriinfection and associated side effects[J]. Benef Microbes, 2016, 7 (4): 519-527.

175McFarland LV, Huang Y, Wang L, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: Multi-strain probiotics as adjunct therapy forHelicobacterpylorieradication and prevention of adverse events[J]. United European Gastroenterol J, 2016, 4 (4): 546-561.

(2017-04-30收稿)

10.3969/j.issn.1008-7125.2017.06.006

*本文通信作者,Email: lunonghua@163.com