Effects of two different tranexamic acid administration methods on perioperative blood loss in total hip arthroplasty: study protocol for a prospective, open-label, randomized, controlled clinical trial

Zhen-yang Hou, Yi-ling Sun, Tao Pang, Dong Lv, Biao Zhu, Zhen Li, Xing-yu Chai, Zheng-wen Xu,Chang-zheng Su, *

1 Department of Joint Surgery, Tengzhou Central People’s Hospital, Tengzhou, Shandong Province, China

2 Second Department of Oncology, Tengzhou Central People’s Hospital, Tengzhou, Shandong Province, China

Introduction

Background

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is commonly performed to treat various hip diseases. The abundant blood supply of the bone at the surgical area, extensive intraoperative lavage,acetabular formation, femoral expansion, and medullary cavity and bone wound bleeding all cause considerable intraoperative and postoperative blood loss. The rate of blood transfusion associated with THA is high, which affects patients’ rehabilitation. Previous studies have shown that 16% to 69% of patients require blood transfusion after first THA1-3, which greatly affects their rehabilitation and increases the risk of transfusion-related infection, hemolysis, immunosuppression, acute lung injury, and death.Reducing perioperative blood loss in THA has become a hot topic for joint surgeons.4

The anti fibrinolytic drug tranexamic acid is a synthetic analog of the amino acid lysine. Its mechanisms of action are the competitive inhibition of fibrinolytic zymogens and noncompetitive inhibition of fibrinolytic enzymes.Tranexamic acid strongly inhibits plasmin-induced fibrin decomposition and reduces fibrinolytic system activity to achieve local hemostasis and reduce bleeding.5,6However, there are several possible routes of administration of tranexamic acid and the best method of administration is not clear.7,8Many studies have con firmed that intravenous administration of tranexamic acid during total knee arthroplasty and THA can signi ficantly reduce postoperative blood loss, blood transfusion volume and need for blood transfusion.9-11Intra-articular application of tranexamic acid can reduce the drainage volume, total blood loss,blood transfusion volume and need for blood transfusion after joint arthroplasty. Moreover, hemoglobin levels are markedly higher after surgery in patients receiving intraarticular tranexamic acid than in those not receiving the drug. An increasing number of studies and meta-analyses have veri fied that tranexamic acid has a “target effect”.Reasonable use of tranexamic acid does not increase the risk of deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolism after hip or knee arthroplasty.12In addition, tranexamic acid has a good potency ratio.4

Main objective

The aim of this prospective study is to compare two administration methods of tranexamic acid in patients undergoing a first unilateral THA to explore the effects of the drug on perioperative blood loss, including visible blood loss,hidden blood loss, need for blood transfusion, mean blood transfusion volume, and safety. This information will further clarify which administration method is more effective in THA patients.

Methods/Design

Study design

Prospective, single-center, open-label, randomized, controlled, clinical trial.

Study setting

Tengzhou Central People’s Hospital, Tengzhou, Shandong Province, China.

Study procedures

For patients with femoral head necrosis with bilateral indications for THA, after arthroplasty on one side, the contralateral arthroplasty will be performed at an appropriate time and as physical condition allows. Among current studies on the different uses of tranexamic acid in preventing perioperative blood loss during total hip replacement,prospective randomized controlled clinical trials have seldom been reported.

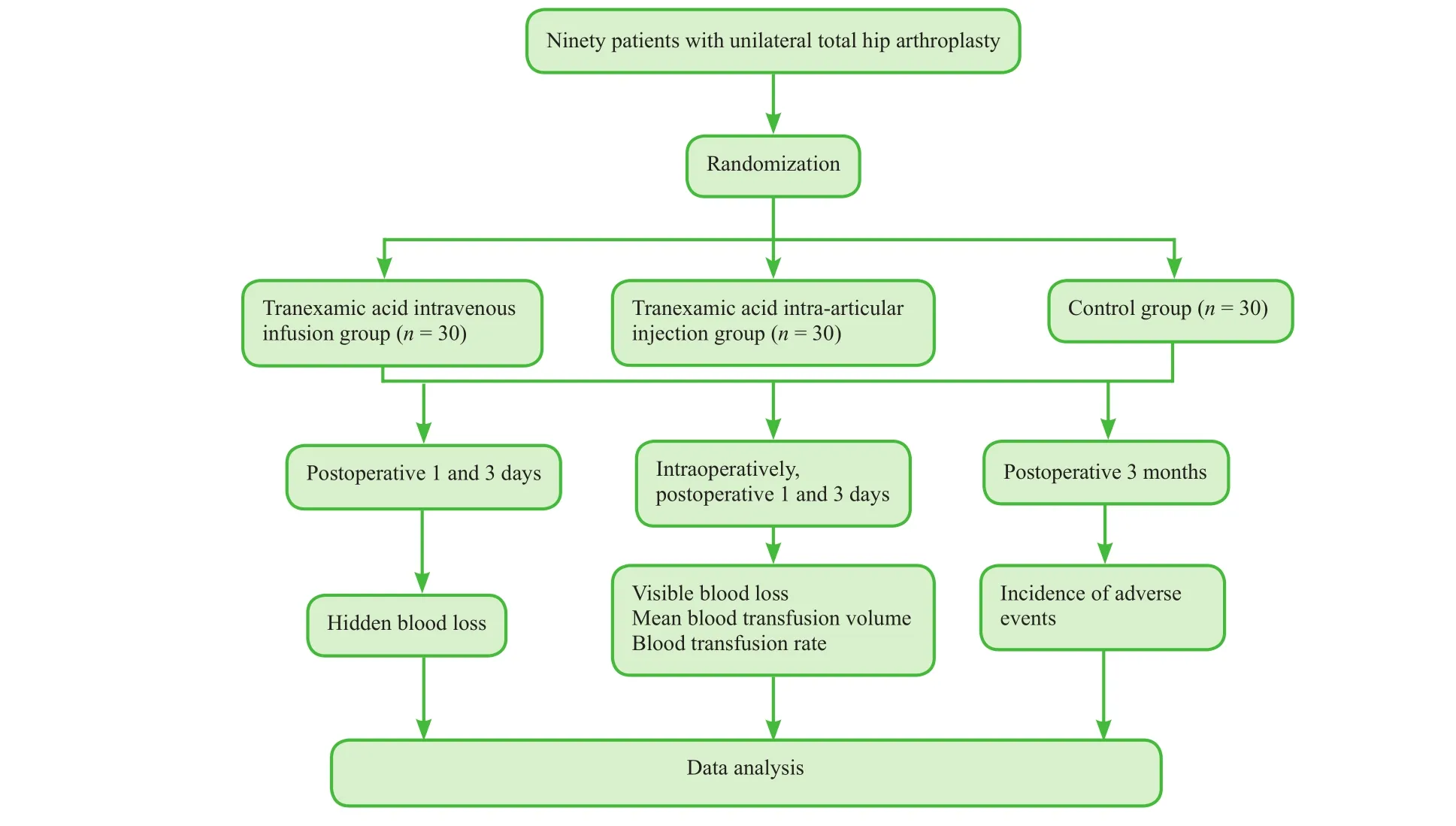

We recruited 90 patients undergoing a first unilateral THA at the Tengzhou Central People’s Hospital from July 2015 to November 2016. Patients were equally and randomly assigned to one of three groups, according to route of tranexamic acid adm finistration during THA: intravenous infusion at the beginning of surgery, intra-articular injection after suturing of deep fascia, or no tranexamic acid administration (control group). Visible blood loss, hidden blood loss, blood transfusion rate, mean blood transfusion volume, and incidence of adverse events at postoperative days 1 and 3 were evaluated.

The trial aims to clarify the more effective method of administering tranexamic acid in first THA and will provide quantitative clinical reference data for safe, rational, and effective use of the drug.

The trial flow chart is shown in Figure 1.

Ethical requirements

The study protocol has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Tengzhou Central People’s Hospital of China,approval number 2015-026.

All protocols will be performed in accordance with the Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects in the Declaration of Helsinki.

The writing and editing of the article will be performed in accordance with the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) (Additional file 1).

This trial has been registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier: NCT03157401).

Written informed consent was provided by each patient and their family members after they indicated that they fully understood the treatment plan.

Figure 1: Flow chart of the trial.

Inclusion criteria

Patients presenting with all of the following criteria were considered for study inclusion:

· Patients with femoral head necrosis or femoral neck fracture undergoing a first unilateral THA

· Signed informed consent

Exclusion criteria

Patients with one or more of the following conditions were excluded from this study:

· Coagulation disorders

· Anemia

· History of infection in the affected extremity

· History of vascular embolism

· Long-term oral anticoagulant drugs

· Contraindications for tranexamic acid or anticoagulant drugs

Sample size

In accordance with our experience, we hypothesized that hidden blood loss would be 560 mL lower in the tranexamic acid intra-articular injection group and 460 mL lower in the tranexamic acid intravenous infusion group than in the control group at postoperative day 1. The standard deviation of hidden blood loss was 300 mL. Taking β = 0.2 and Power = 80% with a signi ficance level of α = 0.05, the final effective sample size of n = 112 patients per group was calculated with PASS 11.0 software (PASS, Keysville, UT,USA). Assuming a patient loss rate of 20%, we required 135 patients per group, for a total of 405 patients. After screening according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria,90 patients were included in the trial (n = 30 per group).

Recruitment

Recruitment information was posted on the Tengzhou Central People’s Hospital bulletin boards. Notice information clari fied the content and risks of the study. Patients contacted the project leader by telephone. After providing informed consent, potential participants who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were enrolled.

Randomization and blinding

This is an open-label trial. Patients, physicians, and assessors were not blinded to group information or therapeutic regimen. Because of differences in the number of males and females and the small sample size, the strati fied randomization method was used to exclude the possible effects of sex.A random number table was generated by computer. Patients were assigned a number. Ninety patients (33 males and 57 females) were randomized into three groups to achieve the same sex ratio in each group (n = 30 per group,including 11 males and 19 females).

Intervention

Tranexamic acid intravenous infusion group: 15 mg/kg tranexamic acid diluted in 100 mL physiological saline was infused intravenously at the beginning of surgery. After suturing of the deep fascia, 20 mL of physiological saline was injected intra-articularly.

Tranexamic acid intra-articular injection group: 100 mL of physiological saline was infused intravenously at the beginning of surgery. After suturing of the deep fascia, a mixture of 1.5 g tranexamic acid and 20 mL physiological saline was injected intra-articularly.

Control group: 100 mL of physiological saline was infused intravenously at the beginning of surgery. After suturing of the deep fascia, 20 mL of physiological saline was injected intra-articularly.

Surgeons: All operations were performed by the same group of doctors.

Hip prosthesis source: Hip prostheses (Stryker Corporation, Kalamazoo, MI, USA) were used for replacement.

Surgical methods: A posterolateral approach was used for hip arthroplasty. Operation time was controlled at 50 to 60 minutes.

Hip arthroplasty: After induction of anesthesia, patients were placed in lateral recumbency. The surgical area was routinely aseptically prepared and covered with a surgical towel. An incision was made posterior to the affected hip.The skin, subcutaneous tissue, and fascia lata were incised sequentially. After incising the gluteus maximus fascia,the gluteus maximus was split in an anterograde direction,exposing the proximal femur. Along the rear of the hip, the quadratus femoris, piriformis, and partial gluteus minimus were incised to expose the posterior acetabular wall and ischial tuberosity. After dislocation of the hip, femoral neck osteotomy was performed. The acetabulum was exposed.Soft tissues of the acetabular rim and acetabular floor were incised to expose the horseshoe-shaped hollow. The acetabulum was filed with an acetabular file until extensive subchondral bleeding was achieved. An acetabular cup was inserted and fixed by tapping. The ceramic lining was placed. The femoral end was expanded with reaming. The femoral prosthesis stem was implanted at approximately 15° of anteversion and secured. The ceramic ball head was placed, followed by traction reduction.

Arthroplasty materials were provided by the Stryker Corporation. The hip stem was made of titanium-6 aluminum-4 vanadium alloy. The middle of the hip stem was coated with hydroxyl-tricalcium phosphate (cementless). The outer acetabular cup was made of titanium. The acetabular lining and femoral head were made of OXINIUM (TM) zirconia,which has the advantages of super wear resistance, high strength, stable chemical properties, anti-aging properties,good biocompatibility and durability, and high stability; in addition, the material cannot cause allergies.

Postoperative management: The drainage tube was temporarily closed for 2 hours in each group, and was removed on the morning after surgery. Blood tests were performed in the morning on postoperative days 1 and 3. All patients underwent comprehensive anticoagulant therapy.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measure

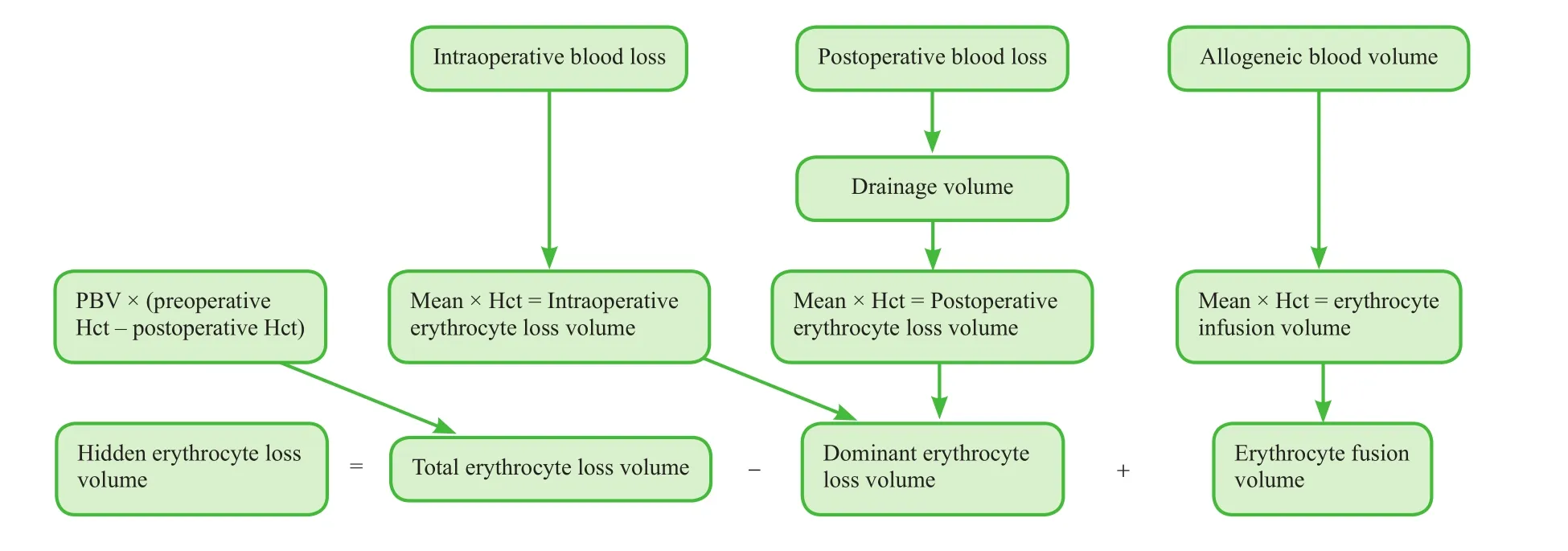

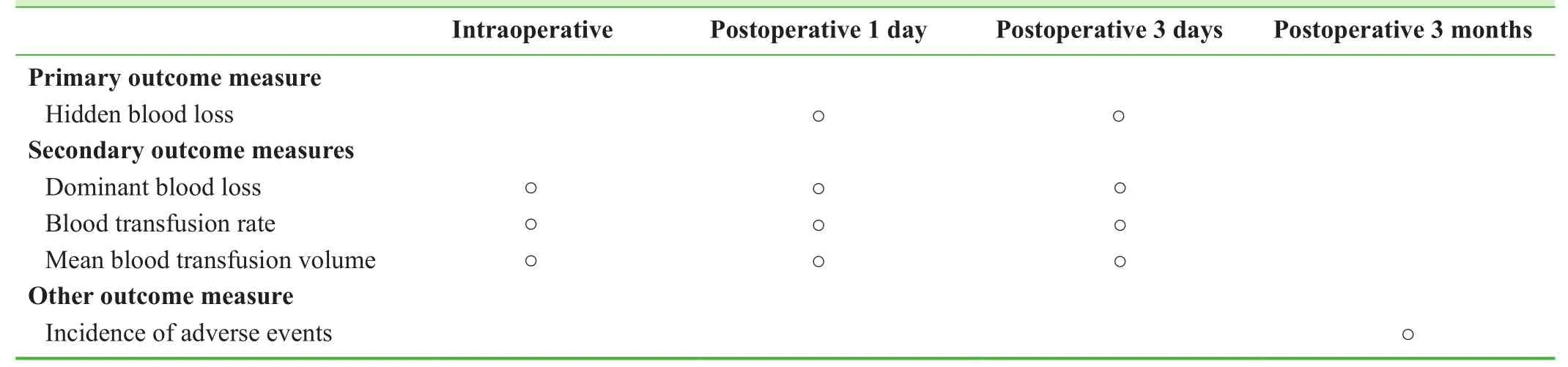

Changes in hidden blood loss at postoperative days 1 and 3: Calculation methods are shown in Figure 2. Hidden blood loss is calculated according to the circulation volume proposed by Gross, i.e.,13total erythrocyte loss is equal to preoperative total blood volume × (preoperative hematocrit– hematocrit 3 days postoperatively). Hidden erythrocyte loss is equal to total erythrocyte loss – visible erythrocyte loss + erythrocyte infusion volume (blood transfusion volume). Hidden erythrocyte loss is converted into hidden blood loss according to perioperative mean hematocrit.

Figure 2: Calculation of dominant and hidden erythrocyte loss volume.

Secondary outcome measures

Visible blood loss intraoperatively and on postoperative days 1 and 3: Calculation methods are shown in Figure 2. Visible blood loss includes intraoperative blood loss and postoperative blood loss. Intraoperative blood loss is quanti fied by measuring irrigation fluid and weighing surgical sponges. Postoperative blood loss is quanti fied by measuring wound drainage volume and weighing surgical sponges. Visible blood loss (i.e., erythrocyte loss) is equal to (intraoperative blood loss + postoperative blood loss) ×(preoperative hematocrit + hematocrit 3 days postoperatively)/2.

Blood transfusion rate intraoperatively and on days 1 and 3 postoperatively: On postoperative days 1 and 3, if hemoglobin levels were lower than 70 g/L and patients showed signi ficant anemia symptoms, leukocyte-free erythrocyte suspension was infused intravenously. During blood transfusion, patients’vital signs and transfusion reactions were closely monitored.Blood testing was performed after transfusion. The incidence of blood transfusion is calculated as the number of patients requiring blood transfusion in each group/the number of patients in each group × 100%. High blood transfusion incidence indicates high postoperative blood loss volume.

Mean blood transfusion volume intraoperatively and at days 1 and 3 postoperatively: Mean blood transfusion volume at postoperative days 1 and 3 re flects postoperative blood loss volume.

Other outcome measure

Incidence of adverse events at postoperative 3 months: To evaluate the occurrence of complications, the incidence is de fined as the number of patients with adverse events in each group/the number of patients in each group.

The schedule of outcome measurement assessments is shown in Table 1.

Adverse events

We recorded adverse events during follow-up, including incision pain, infection, hip pain, peripheral nerve injury,pulmonary embolism, lower extremity hematoma, deep vein thrombosis, and implant loosening.

If severe adverse events occur, investigators report details, including the date of occurrence and measures taken to treat the adverse events, to the principle investigator and the institutional review board within 24 hours.

Data collection, management, analysis, and open access

Data collection: Case report forms were collected and processed using Epidata software (Epidata Association,Odense, Denmark). These data were recorded electronically.

Data management: Tengzhou Central People’s Hospital,China will preserve all data regarding this trial. Only the project manager has the right to query the database file.This arrangement will not be altered.

Data analysis: A professional statistician will statistically analyze the electronic database and create an outcome analysis report. An independent data monitoring committee will supervise and manage the trial data.

Data open access: Anonymized trial data will be published at www. figshare.com.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis will be performed with SPSS 19.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and will follow the intention-to-treat principle.

Normally distributed measurement data will be expressed as the mean ± standard deviation and minimums and maximums. Non-normally distributed measurement data will be expressed as the lower quartile (q1) and median and upper quartiles (q3). Counted data will be expressed as a percentage.

Differences in hidden blood loss, visible blood loss, and mean blood loss in each group intraoperatively and at days 1 and 3 postoperatively will be compared with one-way analysis of variance. Paired comparisons of intergroup data will be conducted with least signi ficant difference test. The incidence of blood transfusion and adverse events in each group will be compared with Pearson χ2test.The signi ficance level will be α = 0.05.

Table 1: Timing of outcome assessments

Table 2: Visible blood loss, hidden blood loss, incidence of blood transfusion, and mean blood transfusion volume

Trial Status

Patient recruitment began in July 2015 and finished in November 2016. Partial data analysis has been finished at the time of submission. Partial results are as follows.

Effects of tranexamic acid on visible blood loss, hidden blood loss, incidence of blood transfusion, and mean transfusion volume after cementless THA

Visible blood loss, hidden blood loss, incidence of blood transfusion, and mean blood transfusion volume were lower in both tranexamic acid groups than in the control group during surgery (P < 0.05). Hidden blood loss was lower in the intravenous tranexamic acid infusion group than in the intra-articular tranexamic acid injection group (P < 0.05;Table 2).

Comparison of the incidence of adverse events in each group

No infection, pulmonary embolism, joint hematoma, or deep vein thrombosis of the lower extremity occurred during hospital stay in any group. Sutures were removed from all patients and patients were discharged within 14 days after surgery. Incisions healed well. At 3 months after surgery, no deep vein thrombosis of the lower extremity or pulmonary embolism occurred.

Discussion

Significance of this study

THA is extensively used to treat various hip disorders,including femoral neck fracture, femoral head necrosis,and congenital acetabular dysplasia. Moreover, surgical skills are becoming more advanced. However, considerable perioperative bleeding occurs with the procedure. If blood transfusion is indicated to ensure the safety of patients in the perioperative period, allogeneic blood is required, incurring the risk of complications of blood transfusion and increased medical costs. Anti fibrinolytic agents can reduce perioperative bleeding, but may increase the risk of deep vein thrombosis after surgery.

Tranexamic acid is a commonly used anti fibrinolytic drug that competitively inhibits plasminogen binding to fibrin,preventing fibrin degradation and dissolution by plasmin,thereby preserving hemostasis.14Our results demonstrate that both intravenous administration of tranexamic acid at the beginning of surgery and intra-articular injection of tranexamic acid after suturing of the deep fascia can effectively decrease the visible blood loss, incidence of blood transfusion, and mean blood transfusion volume in a first unilateral THA. Previous studies have con firmed that tranexamic acid effectively reduced total blood loss after THA, with an especially obvious effect on reducing visible blood loss, and also reduced the need for allogeneic blood transfusion and volume postoperatively,15,16findings consistent with our results. In this trial, perioperative visible blood loss, incidence of blood transfusion, and mean blood transfusion volume were not signi ficantly different between the intravenous tranexamic acid and intra-articular injection groups.

For patients undergoing THA the decrease in postoperative hemoglobin resulting from hidden blood loss often exceeds clinical expectations. A previous study veri fied that hidden blood loss accounts for 60% of total blood loss during THA.17The mechanisms of hidden blood loss include hemolysis, increased erythrocyte destruction, and interstitial fluid exudation. Details of these mechanisms remain unclear, but strategies to control perioperative blood loss in THA, especially hidden blood loss, have become an important issue. This trial includes hidden blood loss as a research indicator; initial results show that either intravenous administration of tranexamic acid at the beginning of surgery or intra-articular injection of tranexamic acid after suturing of the deep fascia can signi ficantly diminish hidden blood loss after a first unilateral THA.

Tranexamic acid is administered in a variety of ways,including intravenously, intramuscularly, by intra-articular injection, and orally.18-21Previous studies have mainly been controlled trials of tranexamic acid monotherapy at different doses or different time points; few have evaluated different administration methods. In this study, we evaluated two dif-ferent modes of tranexamic acid administration; our results will further clarify the ideal use of the drug. To minimize the heterogeneity of the two tranexamic acid groups and to strengthen the results, all patients in this study received both intravenous and intra-articular administration of either tranexamic acid or physiological saline. We also had a control group. All surgeries were performed by the same senior surgical team. All prostheses are cementless. There were no signi ficant differences in the volume of fluids infused during surgery, so bias caused by surgical techniques and other operations on the study results are minimized. Our results are highly reliable.

Our preliminary findings demonstrate that compared with intra-articular injection of tranexamic acid, intravenous administration signi ficantly reduced postoperative mean hidden blood loss (by approximately 131.19 mL).This finding may be associated with the pharmacokinetics of tranexamic acid. Tranexamic acid administered intravenously can quickly spread to the joint synovial fluid and synovial membrane. Its concentrations there are possibly consistent with serum levels. The half-life of the drug in the synovial fluid is about 3 hours. Tranexamic acid maintains an effective concentration throughout the surgery. Intra-articular injection of tranexamic acid after suturing of the deep fascia cannot achieve effective drug concentration in a timely manner. The different time of administration of these two methods may be the main reason for the difference in hidden blood loss between the methods.

Theoretically, intravenous administration of tranexamic acid should increase the fibrin content in the blood, increasing the risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, whereas intra-articular administration of tranexamic acid should be safer. Several studies have demonstrated that the use of tranexamic acid during THA does not increase the risk of deep vein thrombosis.11,22-26None of the patients in the three groups in the present study had clinical symptoms of deep vein thrombosis, a finding that supports the safety of intravenous and intraarticular use of tranexamic acid. Given the same safety and effectiveness findings of intravenous and intra-articular injection of tranexamic acid, intravenous administration at the beginning of the surgery is simpler and has more clinical value.

Limitations of this study

The sample size of this study is small and the outcome measures are limited, which may induce bias and affect the reliability and accuracy of the results. The results need to be con firmed in future studies with a larger sample size.27,28

Evidence for contribution to future studies

We hope to identify the effects of intravenous infusion of tranexamic acid at the beginning of surgery versus intra-articular injection after suturing of the deep fascia on perioperative blood loss during THA, and to clarify the differences between the two administration routes to provide a scienti fic and rational basis for the use of tranexamic acid in THA. Our preliminary findings suggest that both intravenous infusion of tranexamic acid at the beginning of THA and intra-articular injection of tranexamic acid after suturing of the deep fascia can effectively reduce visible blood loss,hidden blood loss, incidence of blood transfusion, and mean blood transfusion volume, while not increasing the risk of deep vein thrombosis. Intravenous administration is more effective than intra-articular administration in reducing hidden blood loss.

Additional file

Additional file 1: SPIRIT checklist (PDF 52.0 kb).

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patients have given their consent for their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Author contributions

Study design and concept, manuscript writing, critical revision of the manuscript and publication approval: ZYH. Surgery implement and data collection: CZS. Data statistics: YLS. Case data collection: TP, DL and BZ. Literature retrieval and data collection: ZL, XYC and ZWX. Critical revision and evaluation of the manuscript: CZS.

Plagiarism check

This paper was screened twice using CrossCheck to verify originality before publication.

Peer review

This paper was double-blinded and stringently reviewed by international expert reviewers.

1. Alshryda S, Mason J, Sarda P, et al. Topical (intra-articular)tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and transfusion rates following total hip replacement: a randomized controlled trial(TRANX-H). J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:1969-1974.

2. Bruce W, Campbell D, Daly D, Isbister J. Practical recommendations for patient blood management and the reduction of perioperative transfusion in joint replacement surgery. ANZ J Surg. 2013;83:222-229.

3. Zhao J, Li J, Zheng W, Liu D, Sun X, Xu W. Low body mass index and blood loss in primary total hip arthroplasty: results from 236 consecutive ankylosing spondylitis patients. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:742393.

4. Gandhi R, Evans HM, Mahomed SR, Mahomed NN. Tranexamic acid and the reduction of blood loss in total knee and hip arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:184.

5. McCormack PL. Tranexamic acid: a review of its use in the treatment of hyper fibrinolysis. Drugs. 2012;72:585-617.

6. Panteli M, Papakostidis C, Dahabreh Z, Giannoudis PV. Topical tranexamic acid in total knee replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee. 2013;20:300-309.

7. Georgiadis AG, Muh SJ, Silverton CD, Weir RM, Laker MW.A prospective double-blind placebo controlled trial of topical tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty.2013;28:78-82.

8. Konig G, Hamlin BR, Waters JH. Topical tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and transfusion rates in total hip and total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28:1473-1476.

9. Soni A, Saini R, Gulati A, Paul R, Bhatty S, Rajoli SR. Comparison between intravenous and intra-articular regimens of tranexamic acid in reducing blood loss during total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29:1525-1527.

10. Patel JN, Spanyer JM, Smith LS, Huang J, Yakkanti MR, Malkani AL. Comparison of intravenous versus topical tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomized study.J Arthroplasty. 2014;29:1528-1531.

11. Zhou XD, Tao LJ, Li J, Wu LD. Do we really need tranexamic acid in total hip arthroplasty? A meta-analysis of nineteen randomized controlled trials. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2013;133:1017-1027.

12. Aguilera X, Martinez-Zapata MJ, Bosch A, et al. Ef ficacy and safety of fibrin glue and tranexamic acid to prevent postoperative blood loss in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:2001-2007.

13. Cross JB. Esti mating allowable blood loss:corrected for dilution. Anesthesiology. 1983,58:277-280.

14. Panteli M, Papakostidis C, Dahabreh Z, et al. Topical tranexamic acid in total knee replacement: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Knee. 2013;20:300-309.

15. McConnell JS, Shewale S, Munro NA, et al. Reduction of bloodloss in primary hip arthroplasty with tranexamic acid or fibrin spray. A randomized controlled trial. Acta Orthop.2011;82:660-663.

16. Zhao QB, Ren JD, Zhang XG, et al. Comparison of perioperative blood loss and transfusion rate in primary unilateral total hip arthroplasty by topical, intravenous application or combined application of tranexamic acid. Zhongguo Zuzhi Gongcheng Yanjiu. 2016;20:459-464.

17. Martin JG, Cassatt KB, Kincaid-Cinnamon KA, et al. Topical administration of tranexamic Acid in primary total hip and total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29:889-894.

18. Oremus K, Sostaric S, Trkulja V, Haspl M. In fluence of tranexamic acid on postoperative autologous blood retransfusion in primary total hip and knee arthroplasty; a randomized controlled trial. Transfusion. 2014;54:31-41.

19. Wong J, Abrishami A, El BH, et al. Topical application of tranexamic acid reduces postoperative blood loss in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:2503-2513.

20. Maniar RN, Kumar G, Singhi T, et al. Most effective regimen of tranexamic acid in knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomized controlled study in 240 patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res.2012;470:2605-2612.

21. Gandhi R, Evans HM, Mahomed SR, et al. Tranexamic acid and the reduction of blood loss in total knee and hip arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:184.

22. Xie JW, Yue C, Pei FX, et al. A retrospective study on the efficacy and safety of tranexamic acid for reducing perioperative bleeding during primary cementless total hip arthroplasty.Zhongguo Gu yu Guanjie Waike. 2014;7:481-485.

23. Yue C, Kang P, Pei F, et al. Topical application of tranexamic acid in primary total hip arthroplasty: a randomized doubleblind controlled trial. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29:2452-2456.

24. Alshryda S, Sukeik M, Sarda P, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the topical administration of tranexamic acid in total hip and knee replacement. Bone Joint J. 2014;96:1005-1015.

25. Singh J, Ballal MS, Mitchell P, et al. Effects of tranexamic acid on blood loss during total hip arthroplasty. J Orthop Surg.2010;18:282.

26. Kazemi SM, Mosaffa F, Eajazi A, et al. The effect of tranexamic acid on reducing blood loss in cementless total hip arthroplasty under epidural anesthesia. Orthopedics. 2010;33:17.

27. Wu T, Zhang GQ (2016) Minimally invasive treatment of proximal humerus fractures with locking compression plate improves shoulder function in older patients: study protocol for a prospective randomized controlled trial. Clin Transl Orthop.1:51-57

28. Yin PB, Long AH, Shen J, et al (2016) Treatment of intertrochanteric femoral fracture with proximal femoral medial sustainable intramedullary nails: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Clin Transl Orthop. 1:44-50.

Clinical Trials in Orthopedic Disorder2017年2期

Clinical Trials in Orthopedic Disorder2017年2期

- Clinical Trials in Orthopedic Disorder的其它文章

- Efficacy of endoscopic transantral versus transorbital surgical approaches in the repair of orbital blowout fractures: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial

- Platelet-rich plasma combined with conventional surgery in the treatment of atrophic nonunion of femoral shaft fractures: study protocol for a prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trial

- Effects of lumbar plexus-sciatic nerve block combined with sevoflurane on cognitive function in elderly patients after hip arthroplasty: study protocol for a prospective, single-center,open-label, randomized, controlled clinical trial

- Supercapsular percutaneously-assisted total hip approach for the elderly with femoral neck fractures: study protocol for a prospective, open-label, randomized, controlled clinical trial

- Should angiography be done in suspected tuberculosis of spine in an endemic country? – Hemangioma masquerading as tuberculosis of spine