老年骨肉瘤患者的临床特征与预后

王倩荣 吴晋 刘文超 王臻 张红梅

. 骨肿瘤 Bone neoplasms .

老年骨肉瘤患者的临床特征与预后

王倩荣 吴晋 刘文超 王臻 张红梅

目的 探讨老年骨肉瘤患者的临床特点及预后。方法 收集 2010 至 2013 年我院收治的 30 例老年人 ( ≥60 岁 ) 骨肉瘤病例进行回顾性分析,运用 SPSS 13.0 软件进行统计学分析,预后因素采用 χ2检验;根据相关随访资料统计生存率。结果 30 例中,男 19 例,女 11 例,年龄 60~86 岁,平均 70 岁。28 例平均随访 25 个月,2 例失访,随访率为 93.3%。28 例获随访者均经手术治疗,其中单纯手术治疗 13 例,术后辅助放疗 6 例,术后辅助放化疗 9 例。28 例获随访者中,1 年生存率约 67.8%;3 年生存率为 35.7%。单纯手术切除组与手术联合放化疗组,生存差异有统计学意义 ( P<0.01 )。血清碱性磷酸酶 ( AKP ) 升高者较正常者预后差,差异有统计学意义 ( P<0.05 )。结论 对于老年性骨肉瘤患者手术联合放化疗对改善预后有益。AKP 可作为预测患者预后的指标之一。

骨肉瘤;老年人;术后辅助放疗;术后辅助化疗;外科手术;预后

骨肉瘤是我国最常见的恶性骨肿瘤,以儿童、青少年及年轻成年人为多,统计显示,大约 60% 的骨肉瘤发生于 20 岁以下,发生于 60 岁以上者的骨肉瘤患者大约 10%[1]。骨肉瘤通常多发生于长管状骨的干骺端,最常见于膝关节周围。成人可累及中轴骨和颌面部骨[2]。一直以来,对于中老年骨肉瘤的相关研究甚少。2010 年至 2013 年,我院收治的30 例年龄>60 岁的老年骨肉瘤患者,现就其临床特点及预后回顾分析如下。

资料与方法

一、纳入标准与排除标准

1. 纳入标准:( 1 ) 2010 年至 2013 年,在我院就诊的老年者 ( 年龄≥60 岁 );( 2 ) 病理诊断为骨肉瘤者;( 3 ) 血清碱性磷酸酶 ( AKP ) 正常者 ( 15~120 U / L )。

2. 排除标准:( 1 ) 合并其它器官恶性肿瘤者;( 2 ) 伴有严重内脏器官疾病者。

二、临床资料

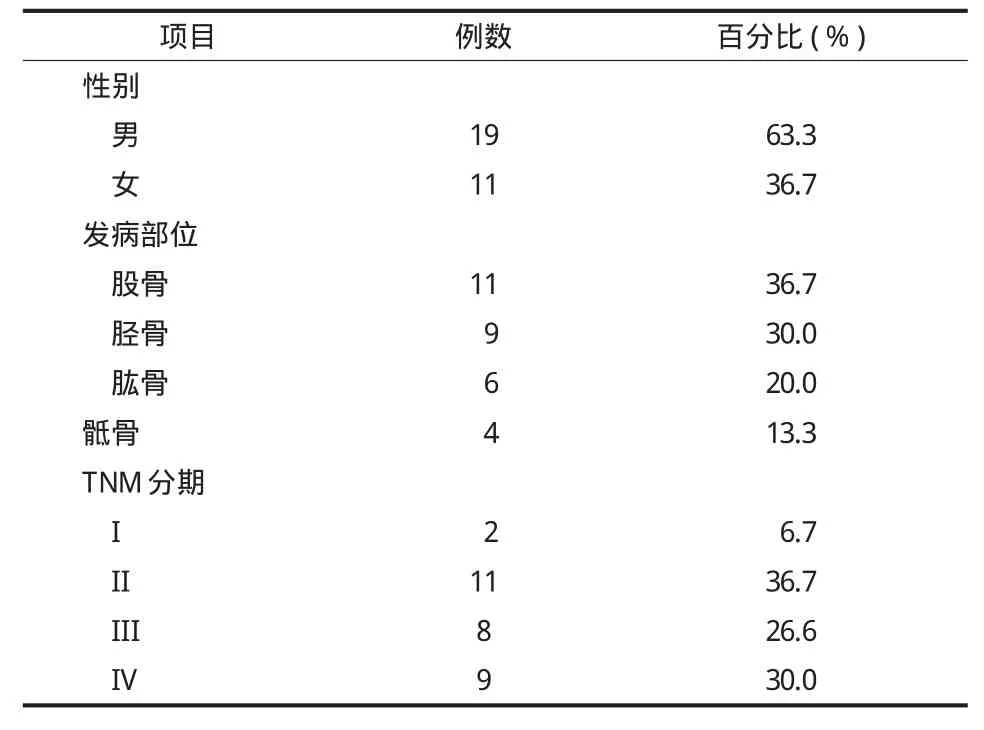

本组共纳入 30 例,男 19 例,女 11 例;年龄60~86 岁,平均 70 岁。发病部位和 TNM 分期见表1。组织学类型参照 WHO 骨肿瘤分类方法[3],TNM 分期参照 UICC 最新骨肉瘤的分期标准[4]。本组 30 例均由经治医师回顾患者的一般资料、手术记录、病理报告,并进行电话随访。

表1 30 例患者的一般资料Tab.1 Baseline characteristics of 30 patients

三、治疗方式

所有随访患者均以手术治疗为首次治疗方式。其中行局部瘤灶切除术 15 例,局部扩大切除术5 例,局部扩大切除加皮瓣移植 3 例,扩大切除加筋膜成型术 3 例,截肢术 2 例 ( 表2 )。

表2 28 例首次手术治疗方式Tab.2 Surgical treatment or other treatment modalities in 28 cases

四、统计学处理

基本资料采用传统的统计学方法 ( SPSS 13.0 软件 ) 进行描述,预后因素的单变量分析采用 χ2检验,P<0.05 为差异有统计学意义。

结 果

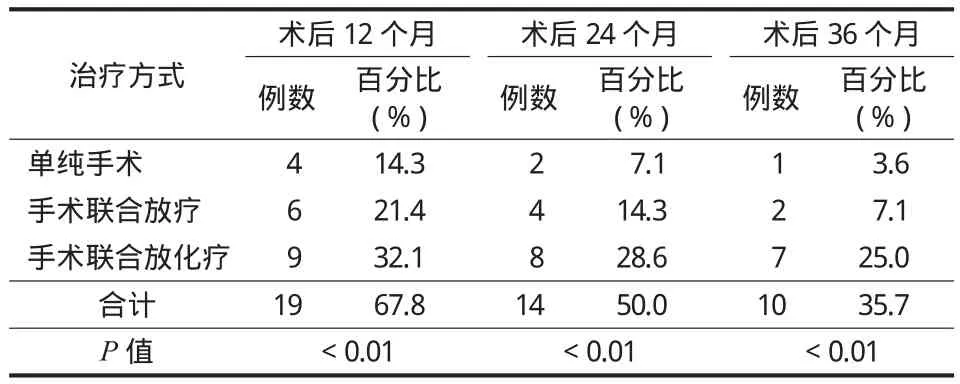

本组 30 例中,28 例随访 4~48 个月,平均25 个月,2 例失访,随访率为 93.3%。28 例获随访者均经手术治疗,其中单纯手术治疗 13 例,术后辅助放疗 6 例,术后辅助放化疗 9 例。术后复发 17 例( 包括单纯手术组 10 例,手术联合放疗组 3 例,手术联合放化疗组 4 例,表3 ),未复发 11 例,复发率60.7%。表4 所示,获随访的 28 例中,1 年、2 年和3 年生存的患者分别为 19 例、14 例和 10 例,存活率分别为 67.8%、50% 和 35.7%,1 年、2 年和 3 年死亡的患者分别为 9 例、14 例和 18 例,病死率分别为 32.1%、50% 和 64.3%。单纯手术切除组与手术联合放化疗组的生存差异有统计学意义 ( P<0.01 )。并且 AKP 升高者较正常者预后差,差异有统计学意义( P<0.05 )。

表3 28 例获随访者的预后情况Tab.3 The prognosis of 28 patients with follow-up information

表4 28 例获随访者术后不同时间的生存情况Tab.4 Overall survival of 28 patients with follow-up at different time points

讨 论

原发性骨肉瘤发病年龄有两个高峰,分别是10~20 岁 ( >80% ) 和>60 岁 ( 约为 13% )。既往报道显示,与青少年骨肉瘤患者相比,老年骨肉瘤四肢骨发病率下降,中轴部位骨骼发病率上升。既往研究认为,大剂量化疗相关不良反应限制了新辅助化疗在老年骨肉瘤患者中的应用,患者预后较差[5-6]。近期观点认为:积极调整化疗方案,可使老年骨肉瘤取得较好的疗效[7-8]。Bacci 等[9]报道了对 29 例位于中老年肢体部位原发性骨肉瘤的治疗情况:25 例 ( 86% )实施保肢手术,4 例 ( 14% ) 实施截肢手术;术前用顺铂、阿霉素;对化疗反应较差的患者术后加用异环膦酰胺、依托泊苷;平均随访 8 年,无瘤存活率达 57%,整体存活率为 62%,没有 1 例死于化疗相关不良反应,取得了良好的长期临床结果。因此,对于老年原发性骨肉瘤的治疗应积极主动[9]。

骨肉瘤通常表现为病变部位酸痛或隐痛,疼痛呈进行性加重,往往由间断性过渡至持续性发作。老年性骨肉瘤患者相对于年轻患者表现出症状轻,病程长,进展相对缓慢的特点。成骨细胞的活性及成骨作用的变化与 AKP 活力密切相关,AKP 水平可以反映成骨细胞活性、手术后病灶有无残留或复发、化疗效果等[10]。文献报道,青少年骨肉瘤患者 AKP 通常明显升高,而成年患者 AKP 多在正常范围内或轻度升高[2],本组 11 例 AKP 升高,约占 36.7%。进一步对预后因素分析显示,AKP 升高者较 AKP 正常患者预后差,差异有统计学意义 ( P=0.01 )。

结合相关文献可以总结出老年骨肉瘤患者与青年骨肉瘤患者的差异为:( 1 ) 临床症状较轻,病程长,进展缓慢;( 2 ) 老年骨肉瘤组织学类型发病顺序大致为混合性、成骨性、溶骨性,本组患者与大宗文献报道一致;( 3 ) 膝关节周围及肱骨近段是骨肉瘤最为好发部位,老年人发生于典型部位者相对较少,本组患者肱骨、胫骨、肱骨及骶骨分别为 11 例 ( 36.67% )、 9 例 ( 30.00% )、6 例 ( 20.00% )、4 例 ( 13.34% ),而Naka 等报告典型部位发生率为 37.5%[11];Huvos 等[12]报告为 14.5%。

Liveestrong 青年联盟根据骨肉瘤新辅助化疗相关前瞻性研究以及注册信息,对骨肉瘤患者性别、年龄及毒性与生存的关系进行了一项荟萃分析[13]。数据包括来自 5 个国际合作团体的 4838 例。结果显示女性患者的总生存率高于男性 ( P=0.005 );儿童患者预后好于青少年及成人 ( P=0.002 )。术后多变量分析表明,化疗诱导后较高的肿瘤坏死率与较长的生存时间相关 ( P<0.001 ),在取得较佳肿瘤坏死结局方面,女性患者高于男性患者 ( P=0.002 ),儿童患者高于成人 ( P<0.001 )。

对本组老年患者的预后相关因素分析结果显示:根治性手术联合放化疗组较单纯手术治疗组预后更好 ( P=0.035 );AKP 升高者较 AKP 正常患者预后差,差异有统计学意义 ( P=0.01 )。

对于中心性骨肉瘤和皮质旁骨肉瘤等低度恶性骨肉瘤,可采用单纯手术治疗。化疗对皮质旁骨肉瘤和颅面部骨肉瘤的作用尚无明确定论。复发性骨肉瘤一般采用手术治疗,预后差,复发后长期生存率<20%。二次手术完全切除后有近 1 / 3 的患者至少存活 5 年。转移性骨肉瘤的治疗同局限性骨肉瘤相似,要求尽量通过手术切除所有转移灶。有 30%转移性骨肉瘤患者和超过 40% 接受较为全面手术的患者可以长期存活[14-16]。

影响预后的不良因素主要包括:( 1 ) 肿瘤位于中轴骨及四肢近端;( 2 ) 肿瘤负荷大;( 3 ) 血 ALP和 LDH;( 4 ) 肿瘤转移灶比肿瘤原发灶对术前化疗的反应性差[17-19]。

总之,老年恶性骨肿瘤患者因年龄大、合并多脏器病变、手术难度大、术中及术后合并症多,须严格掌握手术指征、科学评估患者条件、制订合理的治疗方案,才能获得延长生存期、缓解症状的效果,达到改善生存质量的目的。

[1] He JP, Hao Y, Wang XL, et al. Review of the molecular pathogenesis of osteosarcoma[J]. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev, 2014, 15(15):5967-5976.

[2] Bielack SS, Carrle D, Hardes J, et al. Bone tumors in adolescents and young adults[J]. Curr Treat Options Oncol, 2008, 9(1):67-80.

[3] 张景峰, 王跃. WHO 骨肿瘤分类第四版: 解读与比较[J]. 中华骨科杂志, 2015, 35(9):975-979.

[4] Nimhuircheartaigh J, Browne AM, English C, et al. A Primer and Quiz of the New 7th Edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual/UICC TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours/ Radiological Society of North America 2010 Scientific Assembly and Meeting.

[5] 牛晓辉, 徐海荣. 骨肉瘤的化疗[J]. 中国癌症杂志, 2010, 20(2):81-85.

[6] 杨迪生, 高翔. 老年患者若干骨恶性肿瘤的治疗进展[J]. 老年医学与保健, 2007, 13(6):332-335.

[7] 于晓勇, 曹红霞, 罗真. 骨肉瘤治疗的研究进展[J]. 中国医药指南, 2014(26):77-78.

[8] 耿磊, 陈继营, 许猛, 等. 骨肉瘤的治疗进展[J]. 中国矫形外科杂志, 2015, 23(21):1975-1978.

[9] Bacci G, Balladelli A, Palmerini E, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for osteosarcoma of the extremities in preadolescent patients: the Rizzoli Institute experience[J]. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol, 2008, 30(30):908-912.

[10] Moore DD, Luu HH. Osteosarcoma[J]. Cancer Treat Res, 2014, 162:65-92.

[11] Oda Y, Naka T, Takeshita M, et al. Comparison of histological changes and changes in nm23 and c-MET expression between primary and metastatic sites in osteosarcoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study[J]. Hum Pathol, 2000, 31(6):709-716.

[12] Huvos AG. Osteosarcoma in adolescents and young adults: new developments and controversies. Commentary on pathology[J]. Cancer Treat Res, 1993, 62:375-377.

[13] Collins M, Wilhelm M, Conyers R, et al. Benef ts and adverse events in younger versus older patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy for osteosarcoma: findings from a metaanalysis[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2013, 31(18):2303-2312.

[14] Bacci G, Rocca M, Salone M, et al. High grade osteosarcoma ofthe extremities with of primary lung metastases at presentation: treatment withneoadjuvant chemotherapy and simultaneous resection and metastatic lesions[J]. J Surg Oncol, 2008, 98(6):415-420.

[15] Chou AJ, Merola PR, Wexler LH, et al. Treatment of osteosarcoma at first recurrence after contemporary therapy: he Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center experience[J]. Cancer, 2005, 104(10):2214-2221.

[16] Hughes DP. Strategies for the targeted delivery of therapeutics for osteosarcoma[J]. Expert Opin Drug Deliv, 2009, 6(12): 1311-1321.

[17] Ferrari S, Briccoli A, Mercuri M, et al. Postrelapse survival in osteosarcoma of the extremities: prognostic factors for longterm survival[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2003, 21(4):710-715.

[18] Kager L, Zoubek A, Pötschger U, et al. Primary metastatic osteosarcoma: presentation and outcome of patients treated on neoadjuvant Cooperative Osteosarcoma Study Group protocols[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2003, 21(10):2011-2018.

[19] Mialou V, Philip T, Kalifa C, et al. Metastatic osteosarcoma at diagnosis: prognostic factors and long term outcome--the French pediatricexperience[J]. Cancer, 2005, 104(5): 1100-1109.

( 本文编辑:李贵存 )

Clinical features and prognosis of osteosarcoma in elderly patients

WANG Qian-rong, WU Jin, LIU Wen-chao,WANG Zhen, ZHANG Hong-mei. Department of Clinical Oncology, Xijing Hospital, the fourth Military Medical University, Xi’an, Shanxi, 710032, China

ZHANG Hong-mei, Email: zhm@fmmu.edu.cn

ObjectiveTo investigate the clinical features and prognosis of osteosarcoma in elderly patients.MethodsThe 30 elderly cases of osteosarcoma ( over 60 years old ) collected in our hospital from 2010 to 2013 were analyzed retrospectively. SPSS 13.0 software was applied for statistical analysis and the χ2test was performed for prognostic factors. The survival rate was calculated according to the follow-up information.ResultsThere were 19 males and 11 females, with a mean age of 70 years old ( range: 60 - 86 years ). Among the 30 cases, 28 cases were followed up for an average period of 25 months and the follow-up rate was 93.3%, with 2 cases of loss of follow-up. All the 28 cases received operation therapy, among whom only surgical treatment was performed in 13 cases, postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy in 6 cases, and postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy in 9 cases. The average one-year and 3-year survival rates of all the 28 targeted patients were about 67.8% and 35.7%, respectively. There were statistically signif cant differences in survival between the sole surgical resection group and postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy group ( P < 0.01 ). The patients with elevated alkline phosphatase ( AKP ) had poorer prognosis than normal subjects, with statistically signif cant differences ( P < 0.05 ).ConclusionsSurgery combined with radiotherapy and chemotherapy can help to improve the prognosis of elderly patients with osteosarcoma. AKP can be used as one of effective indicators to predict the prognosis of the patients with osteosarcoma.

Osteosarcoma; Aged; Postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy; Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy; Surgical operative; Prognosis

10.3969/j.issn.2095-252X.2017.02.004

R738.1

国家自然科学基金面上项目 ( 81572699 );陕西省科学技术研究发展计划项目( 2013KJXX-91 )

710032 西安,第四军医大学西京医院肿瘤科 ( 王倩荣、吴晋、刘文超、张红梅 ),骨肿瘤科 ( 王臻 )

张红梅,Email: zhm@fmmu.edu.cn

2016-11-08 )