间充质干细胞改善实体器官移植效果的临床研究

谭建明 王萍

·专家论坛·

间充质干细胞改善实体器官移植效果的临床研究

谭建明 王萍

综述在临床实体器官移植(SOT)中使用间充质干细胞(MSC)的临床试验结果和研究进展。现已发现从人体不同组织中获得的MSC均有组织修复与免疫调节的功能。以MSC为基础的治疗方法旨在减少缺血-再灌注性损伤和促进免疫耐受。目前的临床研究结果显示:在SOT中使用自体或异体MSC是安全有效地。整体而言,活体亲属肾移植受者使用MSC与改善移植后肾功能、减少排斥反应等密切相关,并可替代免疫诱导和降低免疫抑制剂用量。目前已完成的改善SOT预后的临床试验以评估包括使用MSC的细胞治疗方法的安全性、可行性和有效性。结果支持基于MSC的细胞治疗具有安全性并证实可改善移植后近期疗效。

间质干细胞; 器官移植; 组织疗法; 临床试验

细胞、组织与器官移植的目标是最大程度的恢复基因遗传缺陷,炎症、中毒或外伤造成的器官失功。细胞治疗作为改善、减少、修复和治疗疾病的方法而出现。间充质干细胞(mesenchymal stem cells,MSC)由于具备组织修复与免疫调节的潜在功能[1-2],而成为最主要的参与者。本文旨在综述和探讨MSC在实体器官移植(solid organ transplantation,SOT)中应用的临床试验结果与进展[3-17]。

一、MSC在SOT中的应用原理

MSC由同源的细胞群体组成[18-21]。在2006年《国际细胞治疗(International Society for Cellular Therapy,ISCT)指导方针》中指出,MSC的特性包括:(1)贴壁生长;(2)在MSC群体中≥95﹪的细胞均表达CD155,CD73与CD90,必须缺少表达(≤2﹪)CD45,CD34,CD14/CD11b,CD79a/人类白细胞抗原(human leukocyte antigen,HLA)-Ⅱ型;(3)多能分化性(在体外特定的分化条件下可以分化为成骨细胞、脂肪细胞与成软骨细胞)[19]。有益的MSC来源于骨髓,脂肪组织,脐带以及他人的人体组织[22-24],原因是这些均起源于血管周(外皮)

细胞[25-29]。

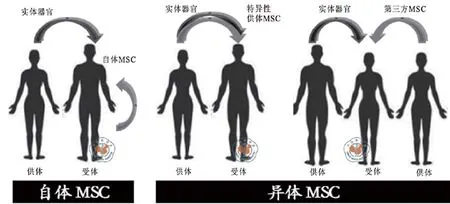

自体的MSC是从患者自身的组织或者与患者HLA完全相同的亲属组织中获得。异体的MSC可以从特定的捐赠者(如果捐赠的是实体器官)或者是与患者HLA相匹配(不相匹配)的第三方个体获

得(图1)。还可以使用先前从活体移植供者或者受者的体内获得冻存的MSC。当没有别的选择时,第三方(库存)同种异体MSC也是一个选择[23-30]。

图1 MSC的来源示意图

在SOT中缺血—再灌注损伤是由大脑、心脏和器官死亡引起的,这一损伤会导致缺氧介导的细胞死亡同时激活在血管内皮与实体器官的薄壁组织中压力介导的信号转导途径。缺血—再灌注损伤的后果包括:作用延迟与原发性的失功、器官免疫原性提高(由于增加相容性复合物分子)炎症介质的表达增加与适应性免疫的激活。事实上,尸体器官捐赠的排斥发生概率大于活体捐赠[29-30]。

体内输注MSC后,MSC首先定居于血管损伤与发生炎症的部位,这些轻微的损伤部位作为MSC天然的居住地[31-32]。MSC的这些特点会帮助缓和免疫排斥反应[33-34],拯救边缘捐赠器官,减低自体免疫激活所致的组织纤维化进程,并且阻断导致免疫耐受的“危险通路”。

免疫抑制的发生通常会结合一些因子,包括淋巴细胞清除因子[如:淋巴细胞球蛋白兔抗(RATG),抗CD25抗体(白介素2受体的靶点),抗CD52抗体(阿伦佐单抗),CD3抗体等],钙神经素抑制剂(calcineurin inhibitor,CNI)[环孢素A(Cyclosporin A,CsA),他克莫司],雷帕霉素的分子靶点抑制剂(西罗莫司与依维莫司),嘌呤/嘧啶合成抑制剂[(麦考酚酯-MMF,霉酚酸-MPA,硫唑嘌呤-AZA),环磷酰胺(Cyp)和甾体类药物]。免疫抑制会增加机会性感染或器官中毒的危险[35-36],同时影响移植后患者的生存质量与移植存活率。移植受体获得永久性免疫耐受,且不需要长时间的抗排斥反应治疗,那就代表移植免疫生物学的“圣杯”,但是这种报道是很少的,并且是在有限的群体中[37-43]。

MSC对免疫调节的影响被认为是基于T细胞,B细胞,NK细胞,树突状细胞以及单核细胞的功能,同时诱导调节免疫循环[35-38]。Therasse等[35]描述了在同种异体非人类灵长类动物皮肤移植中MSC的免疫调节作用。Gao[47]和LeBlanc等[48]证实,如不考虑MSC捐赠者的HLA是否匹配,骨髓间充质干细胞(bone marrow - mesenchymal stem cells,BM-MSC)调控作用能够有效地治疗耐甾体类药物受体在造血干细胞(hematopoietic stem cell,HSC)移植后严重移植物抗宿主病(graft-versus host disease,GVHD)。在SOT中,MSC治疗可帮助减少免疫抑制的负担,治疗排斥反应,促进诱导免疫耐受[40-46]。

二、MSC与SOT的临床试验

多种MSC在SOT中的应用已经注册在ClinicalTrials.gov[3-17],但是全世界范围内的数字可能会更高[13]。MSC应用于SOT的临床试验主要集中在肾脏移植,其他SOT,如肝脏、心脏移植中也有涉及,其结果令人鼓舞。

Vanikar等[3]首先报道了使用供者特异脂肪来源的MSC作为非随机试验的一部分,主要的目标是诱导100例终末期肾病患者活体捐赠肾移植

(living donor kidney transplantation,LDKT)的免疫低反应性。治疗包括:供者特异白细胞输注(DST;移植前25 ~ 27 d);抗CD20抗体(利妥昔单抗,6 mg/kg,移植前18 d);兔抗人胸腺细胞球蛋白(ATG 1.5 mg/kg,移植前1 ~ 7 d);未处理的供者骨髓造血干细胞(HSC 200 ml,移植前16 d);非清髓条件下的全身辐照(TBI;定位于隔膜下的淋巴结、脾脏、骨盆和腰椎;200 CGy,5 d);输注细胞包括供者特异脂肪来源的MSC;培养10 d的骨髓细胞和外周血干细胞;前3个月免疫抑制剂:甲基强的松龙(500 mg IV,移植前1 d,0 d,移植后1 d);环孢素(CsA 3 mg•kg-1•d-1)加泼尼松20(mg/d);然后硫唑嘌呤加泼尼松(5 ~ 10 mg/d)维持。对照组(100例)接受相同的治疗,没有使用供者特异脂肪来源的MSC。经过18个月的随访,与对照组相比较,供者特异脂肪来源的MSC组显示移植物生存改善,持续产生低水平的免疫抑制作用。在4年随访时间内也观察到类似的结果[4]。使用供者特异脂肪来源的MSC,606例患者与310例应用三联免疫抑制治疗方案的对照组比较,也能诱导出免疫低反应性。尽管缺乏随机化的分组,缺少没有接受供者特异脂肪来源的MSC的并行对照,但是研究结果仍然具有价值。

Perico等[4]观察自体BM-MSC用于2例晚期肾病患者接受LDKT后的效果。LDKT 1周后,静脉注射BM-MSC(1.7 ~ 2.0)×106个/kg,常规ATG(0.5 mg/kg,移植前0 ~ 6 d)、抗CD25抗体(巴利昔单抗20移植前0 d,移植前4 d)诱导,CNI(CsA)、霉酚酸酯(mycophenolate mofetil,MMF)加泼尼松维持治疗。虽然接受治疗的2例患者血肌酐都有短暂的升高,但1年后均有更好的移植肾功能。与历史对照相比(接受相同的免疫抑制剂而没有应用MSC),2例患者均表现出CD4+CD25highFoxP3+CD127免疫调节细胞(Regulatory cell,Treg)增加,而CD8+CD45 RO+RA–T记忆细胞减少。另2例患者的配对研究以评估在标准免疫抑制方案条件下,给予自体BM-MSC[3]和不使用CD25拮抗剂[10]的效果。在LKDT前1 d,给予BM-MSC(2.0×106个/kg),1例HLA高度错配的患者术后两周出现血肌酐升高,病理证实为急性细胞性排斥,予以激素冲击治疗而愈。体外CD8阳性T细胞功能检测显示,对供者的抑制强度大于第三方抗原,表现为对供者抗原的反应递增,然后回到基线值。经过12个月免疫抑制治疗的历史对照组,应答第三方抗原不受影响。在标准免疫抑制治疗(加抗CD25抗体)的历史对照组中,T-记忆/效应细胞的比例随着时间的增加而增加,而BM-MSC治疗者,术后第7天显著降低,并在持续一年的随访中仍然低于移植前的水平。与之前的实验结果不同的是[4],除移植后早期有短暂的减少外,Treg细胞没有受到MSC输注的影响[12]。尽管样本量小,缺乏随机对照分配,但这2个实验初步确认了输注自体MSC在SOT中的应用是安全的,并且提供了一个合理的作用机制的实验依据。

Tan团队[6-7]完成了为期1年的前瞻性、非盲、随机化的临床试验。本实验通过随访观察159例终末期肾病LKDT病例,比较自体BM-MSC输注与抗CD25抗体(巴利昔单抗)诱导治疗的利弊[5]。对照组(n = 51)接受抗CD25抗体与标准剂量的CNI(CsA或者他克莫司)联合治疗。在2个实验组中,抗CD25抗体治疗被BM-MSC输注(肾移植开放血流前和移植后第14天,静脉注射(1 ~ 2)×106个/kg所替代,再加上标准剂量(n = 52)与低剂量CNI(标准剂量的80﹪;n = 52)的三联免疫抑制治疗。采用低剂量免疫抑制剂目的是为了减少其肝肾等靶器官的毒性损害[49-50]。主要目标是为期一年经活检确诊的急性排斥发病率和估算的肾小球的滤过率(eGFR)。次要目标是移植物和患者的一年存活率与不良事件发生的概率。结果显示LKDT受者输注MSC替代抗CD25抗体诱导治疗后明显改善移植效果并有良好的安全性,与对照组比较:(1)明显改善移植后前1个月以及移植后1年随访期移植肾功能(可能的影响因素是降低了缺血—再灌注损伤和急性排斥这两个影响移植失败的公认危险因素)[29,51]。(2)明显降低急性排斥反应发生率及排斥的严重程度(实验组没有激素抵抗型并需要ATG治疗的急性排斥,而在对照组中7.8﹪)。(3)低剂量的CNI和较少的不良事件发生率,特别是机会性感染(opportunistic infections,OI)。类似的低剂量CNI结合各种类型来源的MSC在肾移植中的临床试验中也有相同结果的报道[52,54]。

MSC分泌的免疫调节分子(如:抗菌肽hCAP-18/LL-37)[55]可能是导致OI发生率明显减少的因素之一。之前的报道指出,在持续CNI治疗的活体移植受者只有接受全部或者部分的供体特异性BM细胞移植或者使用抗CD25抗体(缺少细胞治疗)才有相似的肾存活率,而后者的使用会增加严重的OI发生率[56]。在中国的肾移植受体中OI的

发生大多数在术后半年内,并增加了病死率[57]。

Peng等[8]评估了使用供体BM-MSC在活体肾移植的安全性与有效性(非随机试验)。所有患者均接受环磷酰胺与甾体类药物诱导,随后使用MMF联合泼尼松维持免疫抑制治疗。CNI(他克莫司)在移植后的第4天开始使用;对照组接受标准剂量(0.07 ~ 0.08 mg•kg-1•d-1;n = 6),实验组(n = 6)接受低剂量(0.04 ~ 0.05 mg/kg)。肾动脉再灌注时输注BM-MSC 5×106个/kg,一个月后再次静脉输注2× 106个/kg。将MSC直接从肾动脉输注也是可以的。在为期1年的随访中,接受MSC与低剂量CNI维持的实验组,移植器官的功能良好,并连续3个月出现高数量的外周B-记忆细胞(CD27+细胞)。没有观察到其他指标之间的差异(比如:淋巴细胞表型、细胞因子、体外单向混合淋巴细胞反应和嵌合现象等)。

Lee等[9]将供体BM-MSC输注到7位HLA不匹配的活体肾移植受者,常规免疫抑制治疗包括ATG(8 ~ 10 d,1.5 mg•kg-1•d-1)诱导,CNI、MMF与甾类药物三联疗法。肾移植当天,骨内输注(IO:输注到受体的右侧髂骨)BM-MSC1×106个/kg。2例患者出现体内供者特异淋巴细胞和丝裂原诱导的T细胞增殖减少,但无嵌合现象。极少患者中观察到供者特异淋巴细胞或者T细胞增殖和Treg细胞应答。3例患者出现组织活检证实的急性细胞性排斥反应,使用甾体类药物控制;1例患者移植后9 d出现抗体介导的急性排斥反应,经静脉注射免疫球蛋白(IVIG)和血浆置换术获得逆转。对激素敏感的急性排斥反应发生在术后第43天和第613天,另1例在12个月程序性活检时发现,2例患者表现为排斥临界改变、无临床体征、未予治疗。研究者认为内源性BM调控MSC是可行的,将来需要大样本对照研究以确定异体BM-MSC对移植效果的影响。

Reinders等[10]研究发现可以使用自体BMMSC治疗急性细胞性排斥反应和肾间质纤维化与肾小管萎缩(IF/TA)。研究对象为6个HLA不匹配的活体肾移植受体,抗CD25抗体(巴利昔单抗)免疫诱导,三联免疫抑制治疗:CNI(他克莫司或者CsA)+MMF+泼尼松,并经3个月抗病毒药物预防性治疗。与4周组织活检比较,在6个月程序性活检时出现急性细胞性排斥反应或IF/TA升高,1周内给予BM-MSC(1×106个/kg),未改变免疫治疗方案。2例活检证实的排斥反应(分别为Banff 1A mild IF/TA和Banff 1B),经MSC治疗后活检显示排斥与小管炎消失,未出现IF/TA。1例发生在21周的BK-病毒相关性肾病,经输注MSC后治愈,且没有减少免疫抑制剂。输注MSC后二周(终止CMV预防治疗后6周)出现新发CMV感染,在未减少免疫抑制的情况下恢复。1例患者输注MSC后尽管减少了免疫抑制剂,仍持续出现数月的低滴度CMV病毒负载。在输注MSC后12周,体外检测白细胞增殖应答减少。实验结果显示:MSC可用于治疗临床自体肾移植后出现的排斥反应。

Baulier等[11]在猪的肾移植模型中也证实,采用从羊水中分离出来的MSC,经肾动脉输注。3个月后肾功能完全恢复、肾纤维化消除。但仍需要大规模对照临床试验确定MSC的治疗效果,同时定义其与肾纤维化和机会性病毒感染之间的关系。

有证据表明移植MSC可以使得心脏移植造成的心肌损伤恢复[58]。一个可能的机制是在输注MSC后,MSC与受体心肌细胞在MSC介导的修复下进行重塑。作者使用cre/lopx荧光霉素标记注射入靶器官的MSC在活体小鼠体内。人类MSC瞬时表达病毒促溶剂通过胶原被传送到鼠类的心脏。在移植后1 d与1周,探针发现在活体小鼠体内存在生物发光标志的细胞融合,并传送到靶器官(心脏)与远端组织中(比如:胃、小肠与肝脏)。显示出MSC或者MSC扩散后的产物有能力通过循环系统迁移入远端器官与移植物细胞中。

MSC移植入心脏,软骨与其他组织中,可恢复组织功能或者限制免疫系统过度应答。从而修复损伤的心脏组织,改善心脏功能。

有几个MSC在肝移植中应用的临床试验仍在进行中[59]。Obermajer等[59]综述了在短期内使用MSC与低剂量的免疫抑制药物联合促进移植物耐受与潜在再生功能的利益与机制。同时,展现了作者第一例肝脏移植患者使用干细胞产品的临床试验。长期观察发现最小化的使用免疫抑制药物是安全的,并获得了移植后的长期存活与部分耐受。结果提示:基于MSC细胞治疗作为长期减少免疫抑制药物治疗的一个手段之一,它是肝脏移植领域重要的技术进步。

三、关于临床SOT中使用MSC的思考

获取MSC的方法,包括分离(酶促与非酶促)、筛选(如贴壁,基于表皮标志因子的富集等)、扩增(如培养基与补充成分,氧含量等)、评估,还没有完全标准化的设施与解剖来源[23]。2006年ISCT

指导方针[19]提出了改进MSC分离与表面标志物的标准[60-62]。

供体或者受体存在其他复合疾病时(如慢性药物耐受患者:糖尿病,终末期肾病等),是否会对MSC的效果和效力产生负面的影响[63],以及这些影响是否在适当的条件下可以恢复[64-67],目前还没完全阐明。

对一个免疫抑制受体而言,具有多能分化与免疫调节的MSC可能是机体的一个安全隐患。虽然至今为止还没有报道,但MSC在人体内成瘤也成为一种可能[68]。一组历时10年、1 012例的临床试验Meta分析已经证实,尽管这些研究的医疗条件与治疗方案不同,但MSC的临床应用是安全的[69]。MSC可以增加免疫抑制作用,此作用可能会增加病毒感染、淋巴增殖性疾病和渐进性脑白质病等的发生危险。传统预防、密切监测和仔细评估受体的免疫和病毒状态可以及时干预,旨在最大限度地减少风险[15]。

MSC的伴随治疗作用(协同或拮抗)包括MSC活性、潜能和有效性正在研究中。初步建议,CNI与mTOR抑制剂可能会干扰MSC的免疫调节功能,而嘌呤(嘧啶)类的抑制剂(MMF与MPA)则不会[4,70-73],ATG与MSC在体外结合会出现剂量依赖现象[4,73],并与MSC凋亡、体外免疫抑制减弱,以及细胞毒性激活CD8+细胞和NK细胞的溶细胞毒性功能减低等相关[73]。人类MSC暴露于接受ATG治疗的肾移植受者血液中,MSC仅与ATG极少接触,在体外淋巴细胞混合培养并不影响其免疫调节功能[4];添加CsA、MMF或者甾体类药物体外培养,会干扰MSC抑制T细胞应答抗CD3/CD28抗体促有丝分裂反应,但观察到MSC与MMF具有协同作用[4]。

移植MSC(供者特异或者第三方供体)的免疫原性可能负面影响SOT存活。Griffi n等[74]收集到的文献证据显示,给予非工程化、γ-干扰素激活而分化的MSC,可以产生针对供体抗原的细胞(T细胞)和体液(B细胞/抗体)免疫应答。这一重要发现,有待于将来在临床中进一步证实。

虽然现有关于SOT临床试验的设计方案不尽相同(MSC的来源、给予的途径与时间、伴随的免疫治疗与研究终点等),但结果已证实MSC治疗是安全的。

临床广泛使用的细胞出自各个实验室,而标准化的MSC产品包括较高的成本。值得注意的是:现在的管理部门要求细胞治疗在新药安全性、有效性评价前,需要从监管机构获得一个生物许可证,这一过程造成了细胞治疗从基础理论到临床应用过渡中的巨大障碍,并加重了巨大的经济负担。这个问题已经引起了激烈的争论,高成本会阻碍细胞治疗的发展,而这一发展对人类的造福超越了SOT本身[75]。

患者的安全是首要的。临床试验的进行与完成应该在伦理委员会批准和安全监测委员会的监督下进行。建立“细胞治疗应用于SOT”的登记表,收集所有的临界参数与结果,这对细胞治疗应用于SOT的安全性和有效性具有很大的帮助,并且可指导后续的实验设计。选择标准化的测试和跨中心的合作将促进这一领域的发展。

目前正处于一个采用MSC改善SOT临床效果,旨在建立安全、可行与有效的细胞治疗的新型临床试验关键时期。最初的临床试验均强力支持在SOT应用MSC的安全性和有效性,并且具有广阔的发展前景。

1 Uccelli A, Moretta L, Pistoia V. Mesenchymal stem cells in health and disease[J]. Nat Rev Immunol, 2008, 8(9):726-736.

2 Cheng K, Rai P, Plagov A, et al. Transplantation of bone marrowderived MSCs improves cisplatinum-induced renal injury through paracrine mechanisms[J]. Exp Mol Pathol, 2013, 94(3):466-473.

3 Vanikar AV, Trivedi HL, Feroze A, et al. Effect of co-transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells and hematopoietic stem cells as compared to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation alone in renal transplantation to achieve donor hypo-responsiveness[J]. Int Urol Nephrol, 2011, 43(1):225-232.

4 Perico N, Casiraghi F, Introna M, et al. Autologous mesenchymal stromal cells and kidney transplantation: a pilot study of safety and clinical feasibility[J]. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol, 2011, 6(2):412-422.

5 Vanikar AV, Trivedi HL. Stem cell transplantation in living donor renal transplantation for minimization of immunosuppression[J]. Transplantation, 2012, 94(8):845-850.

6 Tan JM, Wu W, Xu X, et al. Induction therapy with autologous mesenchymal stem cells in living-related kidney transplants: a randomized controlled trial[J]. JAMA, 2012, 307(11):1169-1177.

7 Tan JM, Pileggi A, Ricordi C. Stem cell therapy in kidney transplantation reply[J]. JAMA, 2012, 308(2):130-131.

8 Peng YW, Ke M, Xu L, et al. Donor-Derived mesenchymal stem cells combined with Low-Dose tacrolimus prevent acute rejection after renal transplantation: a clinical pilot study[J]. Transplantation, 2013, 95(1):161-168.

9 Lee H, Park JB, Lee S, et al. Intra-osseous injection of donor mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) into the bone marrow in living donor kidney transplantation; a pilot study[J]. J Transl Med, 2013, 11:96.

10 Reinders ME, De Fijter JW, Roelofs H, et al. Autologous bone marrow-

derived mesenchymal stromal cells for the treatment of allograft rejection after renal transplantation: results of a phase I study[J]. Stem Cells Transl Med, 2013, 2(2):107-111.

11 Baulier E, Favreau F, Le Corf A, et al. Amniotic fluid-derived mesenchymal stem cells prevent fi brosis and preserve renal function in a preclinical porcine model of kidney transplantation[J]. Stem Cells Transl Med, 2014, 3(7):809-820.

12 Perico N, Casiraghi F, Gotti E, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells and kidney transplantation: pretransplant infusion protects from graft dysfunction while fostering immunoregulation[J]. Transpl Int, 2013, 26(9):867-878.

13 Squillaro T, Peluso G, Galderisi U. Clinical trials with mesenchymal stem cells: an update[J]. Cell Transplant, 2016, 25(5):829-848.

14 Benseler V, Obermajer N, Johnson CL, et al. MSC-based therapies in solid organ transplantation[J]. Hepatol Int, 2014, 8(2):179-184.

15 Mudrabettu C, Kumar V, Rakha A, et al. Safety and efficacy of autologous mesenchymal stromal cells transplantation in patients undergoing living donor kidney transplantation: a pilot study[J]. Nephrology (Carlton), 2015, 20(1):25-33.

16 Bank JR, Rabelink TJ, De Fijter JW, et al. Safety and efficacy endpoints for mesenchymal stromal cell therapy in renal transplant recipients[J]. Journal of immunology research, 2015 (15):391797.

17 Detry O, Jouret F, Vandermeulen M, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells and organ transplantation[J]. Rev Med Liege, 2014, 69 Spec No(9):53-56.

18 Caplan AI, Correa D. The MSC: an injury drugstore[J]. Cell Stem Cell, 2011, 9(1):11-15.

19 Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, et al. Minimal criteria for defi ning multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells[J]. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement.Cytotherapy, 2006, 8(4):315-317.

20 Ricordi C. Back to the future:mesenchimal stem cells[J]. CellR4, 2013, 1(2):152-154.

21 Hoogduijn MJ, Betjes MG, Baan CC. Mesenchymal stromal cells for organ transplantation: different sources and unique characteristics?[J]. Curr Opin Organ Transplant, 2014, 19(1):41-46.

22 Strioga M, Viswanathan S, Darinskas A, et al. Same or not the same Comparison of adipose tissue-derived versus bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem and stromal cells[J]. Stem Cells Dev, 2012, 21(14):2724-2752.

23 Menard C, Pacelli L, Bassi G, et al. Clinical-grade mesenchymal stromal cells produced under various good manufacturing practice processes differ in their immunomodulatory properties: standardization of immune quality controls[J]. Stem Cells Dev, 2013, 22(12):1789-1801.

24 De CP. Regenerative medicine for congenital malformation:new opportunities for therapy[J]. CellR4, 2013, 1(2):123-127.

25 Crisan M, Deasy B, Gavina M, et al. Purifi cation and long-term culture of multipotent progenitor cells affi liated with the walls of human blood vessels: myoendothelial cells and pericytes[J]. Methods Cell Biol, 2008, 86:295-309.

26 Crisan M, Yap S, Casteilla L, et al. A perivascular origin for mesenchymal stem cells in multiple human organs[J]. Cell Stem Cell, 2008, 3(3):301-313.

27 Corselli M, Crisan M, Murray IR, et al. Identifi cation of perivascular mesenchymal stromal/stem cells by fl ow cytometry[J]. Cytometry A, 2013, 83(8):714-720.

28 Reinders ME, Dreyer GJ, Bank JR, et al. Safety of allogeneic bone marrow derived mesenchymal stromal cell therapy in renal transplant recipients: the Neptune study[J]. J Transl Med, 2015, 13(13/34):344.

29 Rowart P, Erpicum P, Detry O, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cell therapy in ischemia/reperfusion injury[J]. Journal of immunology research, 2015 (10):602597.

30 Cornelissen AS, Maijenburg MW, Nolte MA, et al. Organ-specific migration of mesenchymal stromal cells: Who, when, where and why?[J]. Immunol Lett, 2015, 168(2):159-169.

31 Chen Y, Xiang LX, Shao JZ, et al. Recruitment of endogenous bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells towards injured liver[J]. J Cell Mol Med, 2010, 14(6B):1494-1508.

32 Cortinovis M, Casiraghi F, Remuzzi G, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells to control donor-specific memory T cells in solid organ transplantation[J]. Curr Opin Organ Transplant, 2015, 20(1):79-85.

33 De Vries DK, Schaapherder AF, Reinders ME. Mesenchymal stromal cells in renal ischemia/reperfusion injury[J]. Front Immunol, 2012, 3:162.

34 Souidi N, Stolk M, Seifert M. Ischemia-reperfusion injury: benefi cial effects of mesenchymal stromal cells[J]. Curr Opin Organ Transplant, 2013, 18(1):34-43.

35 Therasse A, Wallia A, Molitch ME. Management of post-transplant diabetes[J]. Curr Diab Rep, 2013, 13(1):121-129.

36 Guerra G IA, Kidney T. Present,and future[J]. Curr Diab Rep, 2012, 12(5):597-603.

37 Vanikar AV, Trivedi HL, Gopal SC, et al. Pre-transplant co-infusion of donor-adipose tissue derived mesenchymal stem cells and hematopoietic stem cells May help in achieving tolerance in living donor renal transplantation[J]. Ren Fail, 2014, 36(3):457-460.

38 Casiraghi F, Remuzzi G, Perico N. Mesenchymal stromal cells to promote kidney transplantation tolerance[J]. Curr Opin Organ Transplant, 2014, 19(1):47-53.

39 English K, Wood KJ. Mesenchymal stromal cells in transplantation rejection and tolerance[J]. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, 2013, 3(5): a015560.

40 Locascio SA, Morokata T, Chittenden M, et al. Mixed chimerism, lymphocyte recovery, and evidence for early donor-specific unresponsiveness in patients receiving combined kidney and bone marrow transplantation to induce tolerance[J]. Transplantation, 2010, 90(12):1607-1615.

41 Starzl TE. Immunosuppressive therapy and tolerance of organ allografts[J]. N Engl J Med, 2008, 358(4):407-411.

42 Leventhal J, Abecassis M, Miller J, et al. Tolerance induction in HLA disparate living donor kidney transplantation by donor stem cell infusion: durable chimerism predicts outcome[J]. Transplantation, 2013, 95(1):169-176.

43 Leventhal J, Abecassis M, Miller J, et al. Chimerism and tolerance without GVHD or engraftment syndrome in HLA-Mismatched combined kidney and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation[J]. Sci Transl Med, 2012, 4(124):124-128.

44 Bartholomew A, Sturgeon C, Siatskas M, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells suppress lymphocyte proliferation in vitro and prolong skin graft survival in vivo[J]. Exp Hematol, 2002, 30(1):42-48.

45 Hoogduijn MJ, Popp FC, Grohnert A, et al. Advancement of mesenchymal stem cell therapy in solid organ transplantation (MISOT)[J]. Transplantation, 2010, 90(2):124-126.

46 Franquesa M, Hoogduijn MJ, Reinders ME, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells in solid organ transplantation (MiSOT) fourth meeting: lessons learned from first clinical trials[J]. Transplantation, 2013, 96(3):234-238.

47 Gao L, Liu F, Tan L, et al. The immunosuppressive properties of noncultured dermal-derived mesenchymal stromal cells and the control of graft-versus-host disease[J]. Biomaterials, 2014, 35(11):3582-3588.

48 Le Blanc K, Frassoni F, Ball L, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of steroid-resistant, severe, acute graft-versus-host disease: a phase II study[J]. Lancet, 2008, 371(9624):1579-1586.

49 Ekberg H, Tedesco-Silva H, Demirbas A, et al. Reduced exposure to calcineurin inhibitors in renal transplantation[J]. N Engl J Med, 2007, 357(25):2562-2575.

50 Zhao WY, Zhang L, Han S, et al. Evaluation of living related kidney donors in China: policies and practices in a transplant center[J]. Clin Transplant, 2010, 24(5):E158-E162.

51 Morigi M, Imberti B, Zoja C, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells are renotropic, helping to repair the kidney and improve function in acute renal failure[J]. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 2004, 15(7):1794-1804.

52 Pan GH, Chen Z, Xu L, et al. Low-dose tacrolimus combined with donor-derived mesenchymal stem cells after renal transplantation: a prospective, non-randomized study[J]. Oncotarget, 2016, 7(11):12089-12101.

53 Reinders ME, Bank JR, Dreyer GJ, et al. Autologous bone marrow derived mesenchymal stromal cell therapy in combination with everolimus to preserve renal structure and function in renal transplant recipients[J]. J Transl Med, 2014, 12(10):331.

54 Vanikar AV, Trivedi HL, Kumar A, et al. Co-infusion of donor adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal and hematopoietic stem cells helps safe minimization of immunosuppression in renal transplantation - single center experience[J]. Ren Fail, 2014, 36(9):1376-1384.

55 Krasnodembskaya A, Song Y, Fang X, et al. Antibacterial effect of human mesenchymal stem cells is mediated in part from secretion of the antimicrobial peptide LL-37[J]. Stem Cells, 2010, 28(12):2229-2238.

56 Hanaway MJ, Woodle ES, Mulgaonkar S, et al. Alemtuzumab induction in renal transplantation[J]. N Engl J Med, 2011, 364(20):1909-1919.

57 Tan J, Qiu J, Lu T, et al. Thirty years of kidney transplantation in two Chinese centers[J]. Clin Transpl, 2005:203-207.

58 Freeman BT, Kouris NA, Ogle BM. Tracking fusion of human mesenchymal stem cells after transplantation to the heart[J]. Stem Cells Transl Med, 2015, 4(6):685-694.

59 Obermajer N, Popp FC, Johnson CL, et al. Rationale and prospects of mesenchymal stem cell therapy for liver transplantation[J]. Curr Opin Organ Transplant, 2014, 19(1):60-64.

60 Bourin P, Bunnell BA, Casteilla LA, et al. Stromal cells from the adipose tissue-derived stromal vascular fraction and culture expanded adipose tissue-derived stromal/stem cells: a joint statement of the International Federation for Adipose Therapeutics and Science (IFATS) and the International So[J]. Cytotherapy, 2013, 15(6):641-648.

61 Grisendi G, Annerén C, Cafarelli L, et al. GMP-manufactured density gradient media for optimized mesenchymal stromal/stem cell isolation and expansion[J]. Cytotherapy, 2010, 12(4):466-477.

62 Krampera M, Galipeau J, Shi Y, et al. Immunological characterization of multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells--The International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) working proposal[J]. Cytotherapy, 2013, 15(9):1054-1061.

63 Crop MJ, Baan CC, Korevaar SS, et al. Inflammatory conditions affect gene expression and function of human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells[J]. Clin Exp Immunol, 2010, 162(3):474-486.

64 Yan J, Tie G, Wang S, et al. Type 2 diabetes restricts multipotency of mesenchymal stem cells and impairs their capacity to augment postischemic neovascularization in db/db mice[J]. J Am Heart Assoc, 2012, 1(6):e002238.

65 Liu Y, Li Z, Liu T, et al. Impaired cardioprotective function of transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells from patients with diabetes mellitus to rats with experimentally induced myocardial infarction[J]. Cardiovasc Diabetol, 2013, 12:40.

66 Roemeling-Van RM, Reinders ME, De Klein A, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells derived from adipose tissue are not affected by renal disease[J]. Kidney Int, 2012, 82(7):748-758.

67 Reinders ME, Roemeling-Van Rhijn M, Khairoun M, et al. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells from patients with endstage renal disease are suitable for autologous therapy[J]. Cytotherapy, 2013, 15(6):663-672.

68 Haarer J, Johnson CL, Soeder Y, et al. Caveats of mesenchymal stem cell therapy in solid organ transplantation[J]. Transpl Int, 2015, 28(1):1-9.

69 Lalu MM, Mcintyre L, Pugliese C, et al. Safety of cell therapy with mesenchymal stromal cells (SafeCell): a systematic review and metaanalysis of clinical trials[J]. PLoS One, 2012, 7(10):e47559.

70 Hoogduijn MJ, Crop MJ, Korevaar SS, et al. Susceptibility of human mesenchymal stem cells to tacrolimus, mycophenolic acid, and rapamycin[J]. Transplantation, 2008, 86(9):1283-1291.

71 Buron F, Perrin H, Malcus C, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells and immunosuppressive drug interactions in allogeneic responses: an in vitro study using human cells[J]. Transplant Proc, 2009, 41(8):3347-3352.

72 Eggenhofer E, Renner P, Soeder Y, et al. Features of synergism between mesenchymal stem cells and immunosuppressive drugs in a murine heart transplantation model[J]. Transpl Immunol, 2011, 25(2/3):141-147.

73 Franquesa M, Baan CC, Korevaar SS, et al. The effect of rabbit antithymocyte globulin on human mesenchymal stem cells[J]. Transpl Int, 2013, 26(6):651-658.

74 Griffi n MD, Ryan AE, Alagesan S, et al. Anti-donor immune responses elicited by allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells: what have we learned so far?[J]. Immunol Cell Biol, 2013, 91(1):40-51.

75 Ricordi C. Towards a constructive debate and collaborative efforts to resolve current challenges in the delivery of novel cell based therapeutic strategies[J]. CellR4, 2013, 1(1):e110.

Mesenchymal stem cells to improve solid organ transplant outcome: clinical trials

Tan Jianming,Wang Ping. Fujian Provincial Key Laboratory of Transplant Biology, Fuzhou General Hospital of Nanjing Military Command, Fuzhou 350025, China

We review the recent progress on the clinical use of mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) in solid organ transplantation(SOT). Tissue repairing and immunomodulatory properties have been well recognized for MSC obtained from different human tissues. MSC-based therapy has been proposed to reduce ischemia-reperfusion injury and to promote immune tolerance. The results of recent clinical trial support the safety and promising effects of autologous and allogeneic MSC in SOT. Collectively, the use of MSC in recipients of living donor kidney transplantation (LDKT) is associated with improved graft function and reduced rejection. Dose of maintenance immunosuppressants can also be rduced. The results of the initial clinical trials support the safety of MSC-based therapy and justifying cautious optimism for the immediate future.

Mesenchymal stem cells; Organ transplantation; Tissue therapy;Clinical trial

2016-07-23)

(本文编辑:陈媛媛)

10.3877/cma.j.issn.2095-1221.2016.05.001

国家自然科学基金(81370948);全军“十二五”重点项目(BWS11J004);福建省科技重大专项(2012YZ0001)

350025 福州,南京军区福州总医院 全军器官移植研究所

谭建明,Email:tanjm156@xmu.edu.cn

谭建明,王萍. 间充质干细胞改善实体器官移植效果的临床研究[J/CD].中华细胞与干细胞杂志:电子版, 2016, 6(5):263-269.