甘肃、宁夏奶牛新孢子虫血清流行病学调查及风险因素分析

谭启东,魏邦香,陈 兵,张晓轩,杨言川,秦思源,朱兴全,徐前明,周东辉

(1. 中国农业科学院兰州兽医研究所 家畜疫病病原生物学国家重点实验室,兰州 730046;2. 北京出入境检验检疫局动物隔离场,北京 101312;3. 安徽农业大学动物科技学院,合肥230036;4.榆中县动物疾病预防与控制中心,榆中730000)

·研究论文·

甘肃、宁夏奶牛新孢子虫血清流行病学调查及风险因素分析

谭启东1,2,3,魏邦香4,陈 兵4,张晓轩1,杨言川1,秦思源1,朱兴全1,徐前明3,周东辉1

(1. 中国农业科学院兰州兽医研究所 家畜疫病病原生物学国家重点实验室,兰州 730046;2. 北京出入境检验检疫局动物隔离场,北京 101312;3. 安徽农业大学动物科技学院,合肥230036;4.榆中县动物疾病预防与控制中心,榆中730000)

本研究旨在查明甘肃省与宁夏回族自治区奶牛新孢子虫的感染情况并分析影响其感染的风险因素。采用酶联免疫吸附试验(enzyme linked immunosorbent assay,ELISA)方法检测了甘肃省榆中县、宁夏青铜峡市和宁夏吴忠市3个地方总计1657份奶牛血清样品,并应用流行病学调查及统计学方法对影响奶牛新孢子虫感染的因素进行了分析。流行病学调查结果显示,奶牛新孢子虫抗体总阳性率为8.93%;应用Logistic回归分析评估奶牛新孢子虫感染的风险因素,结果显示奶牛所处地区是影响新孢子虫感染的风险因素(P<0.05)。调查分析表明,甘肃和宁夏地区奶牛新孢子虫普遍流行。应当提高对调查地区奶牛新孢子虫感染的重视,采取适当的综合控制方法和有效的管理措施以防控奶牛新孢子虫病,以保证奶牛养殖业的经济效益。

新孢子虫;ELISA;流行病学;奶牛;甘肃;宁夏

新孢子虫是一种细胞内寄生的原生病原体,在全世界范围内流行,主要引起奶牛流产、死胎以及犬科动物的致命神经系统疾病[1-3]。感染新孢子虫会导致奶牛体重和产奶量下降,从而过早被淘汰,造成重大的经济损失[4-6]。1984年在挪威报道了第1例因狗感染新孢子虫引起神经肌肉病变,从而导致后肢瘫痪的病例[7],随后确定犬科动物是新孢子虫的终末宿主[8,9]。该病原体的传播途径分为垂直传播和水平传播,而经胎盘的垂直传播是奶牛新孢子虫主要传播途径[2]。

许多国家都已经报道了关于奶牛和肉牛新孢子虫病的血清学调查结果[10-16],中国部分地区也进行了新孢子虫感染的相关调查研究[17-21],但是在西北地区甘肃省和宁夏回族自治区,新孢子虫感染情况的调查尚未有报道。本研究的目的是调查甘肃和宁夏地区奶牛新孢子虫感染情况并分析影响其感染的风险因素,以期能为防控奶牛新孢子虫的感染提供依据,从而降低该疾病对畜牧业的危害。

1 材料与方法

1.1 调查区域 选取宁夏回族自治区吴忠市和青铜峡市以及甘肃省榆中县作为奶牛新孢子虫感染情况的调查区域。吴忠市坐落于宁夏的中部地区(35°14′~39°23′N,104°17′~107°39′E),温带大陆性半干旱季风气候,年平均气温为9.4°C。青铜峡市(37°36′~38°15′N,105°21′~106°21′E)为县级市,盛行气候与吴忠市相仿,年平均气温为9.2°C。榆中县位于甘肃省的中部(35°34′~36°26′N,103°49′~104°34′E),大陆性气候显著,年平均气温为6.7°C。奶牛养殖业在这些区域的畜牧业中占有重要地位。

1.2 血清样品 2013年在选取的调查区域共采集1657份奶牛血清样品,其中甘肃省榆中县751份,宁夏回族自治区吴中市456份,青铜峡市450份。血清样品经500×g离心10 min后转移到新的离心管中,-20℃保存待用。记录奶牛的年龄、胎次等重要基本信息。

1.3 血清学检查 血清样品采用酶联免疫吸附试验(ELISA)检测新孢子虫抗体,按照美国IDEXX新孢子虫抗体检测ELISA试剂盒(批号:99-09566)说明书操作。每板设阴、阳性对照,若有可疑孔则进行复检。

1.4 数据分析 采用二元logistic回归分析方法研究采样地区、年龄和胎次3个与新孢子虫感染有关的潜在的风险因素,以P<0.05为具有显著统计学意义的判断标准。所有的数据采用统计软件PASW Statistics 18.0(SPSS Inc., IBM Corporation, Somers, NY)进行分析,并提供结果的优势比(odds ratio,OR)和95%的置信区间(95% confidence interval,95% CI)。当OR值等于1,表示该因素对疾病的发生不起作用;OR值大于1,表示该因素是一个危险因素;OR值小于1,表示该因素是一个保护因素。

2 结果

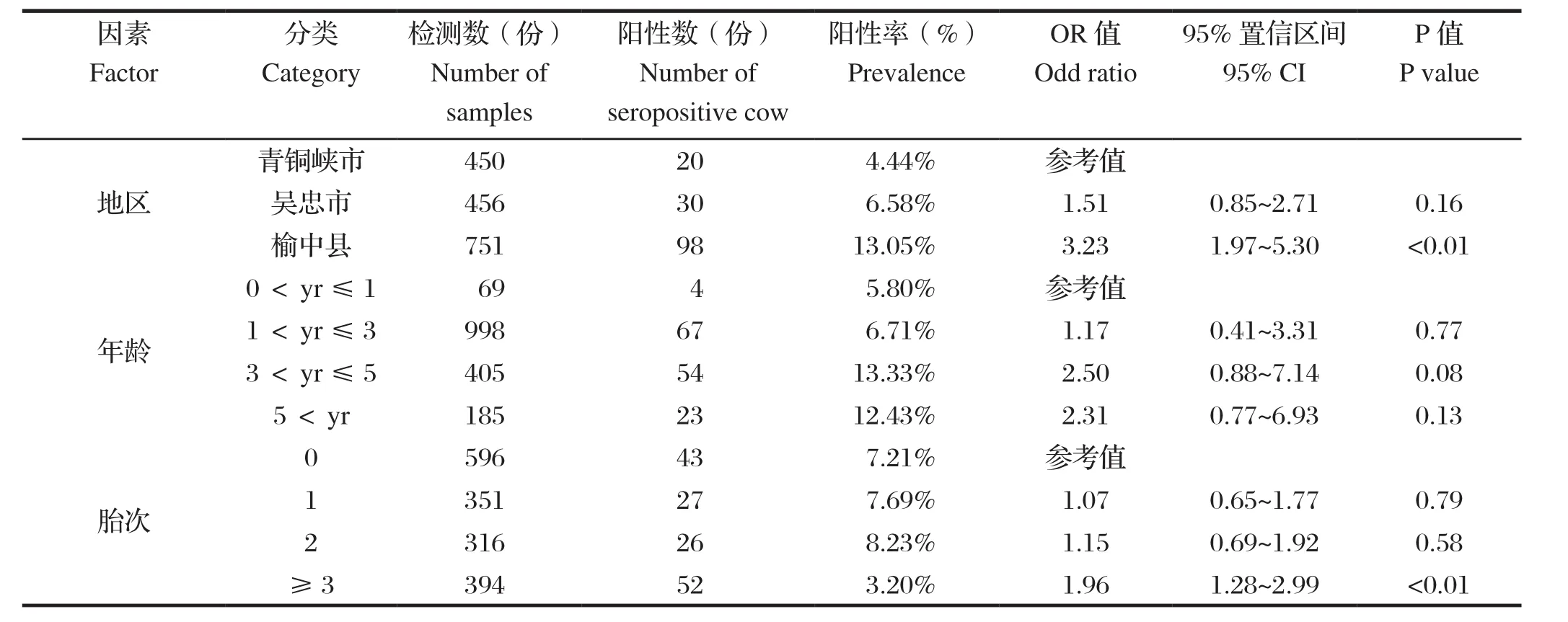

2.1 不同地区奶牛新孢子虫感染结果 检测的1657份奶牛血清样品中,共有148份新孢子虫抗体呈阳性,阳性率为8.93%。甘肃省榆中县、宁夏回族自治区青铜峡市和吴忠市奶牛衣原体阳性率分别为13.05%、4.44%和6.58%(表1)。

2.2 不同年龄奶牛新孢子虫感染结果 4组年龄段奶牛中均发现有阳性样品,阳性率从5.80%到13.33%不等,其中3~5岁的奶牛新孢子虫阳性率最高,其次是大于5岁的年龄段的奶牛,感染率为12.43%,小于1岁的犊牛感染率最低,为5.80%(表1)。

2.3 不同胎次奶牛新孢子虫感染结果 在不同的胎次分组中,产胎多于等于3胎次的的奶牛感染新孢子虫的阳性率最高为13.20%,其次是产胎2次的奶牛,阳性率为8.23%,产胎0次的奶牛感染新孢子虫的阳性率最低,为7.21%(表1)。

表1 甘肃省和宁夏回族自治区奶牛新孢子虫感染阳性率及风险因素的优势比Table 1 Seroprevalence of Neospora caninum infection and odds ratios of risk factors in dairy cattle in Gansu and NXHAR

2.4 影响奶牛新孢子虫的风险因素 运用Logistic回归分析评估影响奶牛新孢子虫感染的风险因素,结果显示奶牛所处的地区是影响新孢子虫感染的一个重要的风险因素,而年龄和胎次不是显著风险因素。榆中市的奶牛感染新孢子虫的风险大约是青铜峡市的3.2倍(OR = 3.23,95% CI = 1.97~5.30, P <0.01),然而吴忠市和青铜峡市之间不存在显著的地区差异(表1)。

3 讨论

犬科动物作为新孢子虫的终末宿主,一经感染,便可持续不断的向外界环境排放卵囊[22]。其他哺乳类动物经摄入被卵囊污染的水或食物从而被感染[5]。奶牛一旦感染新孢子虫,可以通过胎盘传播给后代,不仅给畜牧养殖业带来重大的经济损失,同时还可间接威胁到当地居民的身体健康。

本次调查显示奶牛新孢子虫总体感染率为8.93%,相较于已报道的西班牙(24.1%)[23]、罗马尼亚(27.7%)[13]、巴西(21.6%)[16]等国及我国广东(18.9%)[20]、广西壮族自治区(15.07%)[21]等地区的感染率低,但和伊朗(10.5%)[7]的感染率较为接近。不同地区之间的饲养条件、动物福利和接触污染源的机会等都存在差异,并且各个奶牛场的环境卫生状况、管理模式、防疫情况以及研究所采用的检测方法的敏感性等情况的差别都会影响奶牛新孢子虫的感染状况[1]。

本研究显示榆中县奶牛新孢子虫感染率显著高于青铜峡市和吴忠市,揭示了地区因素是奶牛新孢子虫感染的主要风险因素。由于本次调查的区域气候较为接近,均无相关的免疫措施[24],同时奶牛场内及周边未发现有饲养狗和流浪狗,所以推测调查农场的卫生条件是造成感染率存在差异的主要原因。奶牛可通过摄入被感染犬类排出的卵囊污染的食物或水而感染,同样,犬可通过吞食奶牛的死胎、胎膜等而感染[1],这样就形成了一个恶性循环。消除环境中的流浪狗,定期打扫牛舍并进行彻底消毒可有效降低新孢子虫感染的风险。采样时,我们发现榆中县农场的卫生条件明显较差,奶牛新孢子虫的感染率显著高于青铜峡市和吴忠市。

本研究显示奶牛在3~5岁这个年龄段的新孢子虫感染率最高,为13.33%;其次是大于5岁的年龄段的奶牛,其感染率为12.43%;小于1岁的犊牛感染率最低,为5.80%。但Logistic回归分析显示年龄因素与新孢子虫阳性率之间没有必然联系,年龄因素不是新孢子虫感染的显著风险因素,这与之前Xia等[20]和Wouda等[25]的报道相一致。

本研究同样分析了新孢子虫感染率与胎次间的关系,结果显示,随着生育次数的增加,新孢子虫的阳性率也在逐步增加,但感染率与胎次之间没有显著联系。

综上所述,甘肃省和宁夏回族自治区受调查地区奶牛新孢子虫感染普遍存在,总的阳性率为8.93%。因此,应当提高对调查地区奶牛新孢子虫病的重视,采取适当的综合控制方法和有效的管理措施以防控奶牛新孢子虫病,以保证奶牛养殖业的经济效益。

[1] Dubey J P. Review of Neospora caninum and neosporosis in animals[J]. Korean J Parasitol, 2003, 41(1): 1-16.

[2] Dubey J P, Schares G, Ortega-Mora L M. Epidemiology and control of neosporosis and Neospora caninum[J]. Clin Microbiol Rev, 2007, 20(2): 323-367.

[3] Yildiz K, Kul O, Babur C, et al. Seroprevalence of Neospora caninum in dairy cattle ranches with high abortion rate: special emphasis to serologic co-existence with Toxoplasma gondii, Brucella abortus and Listeria monocytogenes[J]. Vet Parasitol, 2009, 164(2-4): 306-310.

[4] Sedlák K, Bártová E. Seroprevalences of antibodies to Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii in zoo animals[J]. Vet Parasitol, 2006, 136(3-4): 223-231.

[5] Dubey J P, Schares G. Neosporosis in animals--the last five years[J]. Vet Parasitol, 2011, 180(1-2): 90-108.

[6] Woodbine K A, Medley G F, Moore S J, et al. A four year longitudinal sero-epidemiology study of Neospora caninum in adult cattle from 114 cattle herds in south west England: associations with age, herd and dam-offspring pairs[J]. BMC Vet Res, 2008, 4: 35.

[7] Nematollahi A, Jaafari R, Moghaddam G. Seroprevalence of Neospora caninum infection in dairy cattle in Tabriz, northwest Iran[J]. Iran J Parasitol, 2011, 6(4): 95-98.

[8] McAllister M M, Dubey J P, Lindsay D S, et al. Dogs are definitive hosts of Neospora caninum[J]. Int J Parasitol, 1998, 28(9): 1473-1478.

[9] Gondim L F, McAllister M M, Pitt W C, et al. Coyotes (Canis latrans) are definitive hosts of Neospora caninum[J]. Int J Parasitol, 2004, 34(2): 159-161.

[10] Eiras C, Arnaiz I, Alvarez-García G, et al. Neospora caninum seroprevalence in dairy and beef cattle from the northwest region of Spain, Galicia[J]. Prev Vet Med, 2011, 98(2-3): 128-132.

[11] Gavrea R R, Iovu A, Losson B, et al. Seroprevalence of Neospora caninum in dairy cattle from north-west and centre of Romania[J]. Parasite, 2011, 18(4): 349-351.

[12] Cardoso J M, Amaku M, Araújo A J, et al. A longitudinal study of Neospora caninum infection on three dairy farms in Brazil[J]. Vet Parasitol, 2012, 187(3-4): 553-557.

[13] Imre K, Morariu S, Ilie M S, et al. Serological survey of Neospora caninum infection in cattle herds from Western Romania[J]. J Parasitol, 2012, 98(3): 683-685.

[14] Nasir A, Lanyon S R, Schares G, et al. Sero-prevalence of Neospora caninum and Besnoitia besnoiti in South Australian beef and dairy cattle[J]. Vet Parasitol, 2012, 186(3-4): 480-485.

[15] Asmare K, Regassa F, Robertson L J, et al. Seroprevalence of Neospora caninum and associated risk factors in intensive or semi-intensively managed dairy and breeding cattle of Ethiopia[J]. Vet Parasitol, 2013, 193(1-3): 85-94.

[16] Bruhn F R, Daher D O, Lopes E, et al. Factors associated with seroprevalence of Neospora caninum in dairy cattle in southeastern Brazil[J]. Trop Anim Health Prod, 2013, 45(5): 1093-1098.

[17] Yu J, Xia Z, Liu Q, et al. Seroepidemiology of Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii in cattle and water buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis) in the People’s Republic of China[J]. Vet Parasitol, 2007, 143(1): 79-85.

[18] Liu J, Cai J Z, Zhang W, et al. Seroepidemiology of Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii infection in yaks (Bos grunniens) in Qinghai, China[J]. Vet Parasitol, 2008, 152(3-4): 330-332.

[19] Wang C, Wang Y, Zou X, et al. Seroprevalence of Neospora caninum infection in dairy cattle in northeastern China[J]. J Parasitol, 2010, 96(2): 451-452.

[20] Xia H Y, Zhou D H, Jia K, et al. Seroprevalence ofNeospora caninum infection in dairy cattle of Southern China[J]. J Parasitol, 2011, 97(1): 172-173.

[21] Xu M J, Liu Q Y, Fu J H, et al. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum infection in dairy cows in subtropical southern China[J]. Parasitology, 2012, 139(11): 1425-1428.

[22] Corbellini L G, Smith D R, Pescador C A, et al. Herdlevel risk factors for Neospora caninum seroprevalence in dairy farms in southern Brazil[J]. Prev Vet Med, 2006, 74(2-3): 130-141.

[23] Panadero R, Painceira A, López C, et al. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum in wild and domestic ruminants sharing pastures in Galicia (Northwest Spain)[J]. Res Vet Sci, 2010, 88(1): 111-115.

[24] Innes E A, Andrianarivo A G, Bj-rkman C, et al. Immune responses to Neospora caninum and prospects for vaccination[J]. Trends Parasitol, 2002, 18(11): 497-504.

[25] Wouda W, Bartels C J, Moen A R. Characteristics of Neospora caninum-associated abortion storms in diary herds in the Netherlands (1995 to 1997)[J].Theriogenology, 1999, 52(2): 233-245.

SEROPREVALENCE AND RISK FACTORS OF NEOSPORA CANINUM INFECTION IN DAIRY CATTLE IN GANSU AND NINGXIA AREAS

TAN Qi-dong1,2,3, WEI Bang-xiang4, CHEN Bing4, ZHANG Xiao-xuan1,5, YANG Yan-chuan1, QIN Si-yuan1,ZHU Xing-quan1, XU Qian-ming3, ZHOU Dong-hui1

(1. State Key Laboratory of Veterinary Etiological Biology, Lanzhou Veterinary Research Institute, CAAS, Lanzhou 730046, China; 2. Animal Quarantine Station of Beijing Entry-Exit Inspection and Quarantine Bureau, Beijing 101312, China; 3. College of Animal Science and Technology, Anhui Agricultural University, Hefei 230036, China; 4. Yuzhong Animal Disease Prevention and Control Center, Yuzhong 730000, China)

The objective of the present investigation was to examine seroprevalence of N. caninum in dairy cattle in Gansu province and Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region (NXHAR), Northwest China for assessment of the associated risk factors. In this study, a total of 1657 serum samples were collected and tested for the antibodies of N. caninum using a commercially available ELISA kit. The seropositive percentage was 8.93% (148/1657). Then, multiple logistic regression was used to analyze the risk factors associated with seroprevalence.The results of the present survey indicated the widespread of N. caninum infection in Gansu and NXHAR. Thus, comprehensive control strategies and efficient management measures for N. caninum infection should be implemented to increase profit of the dairy cattle industry.

Neospora caninum; ELISA; seroprevalence; dairy cattle; Gansu; Ningxia

S852.723

A

1674-6422(2016)05-0046-05

2016-02-19

国家科技支撑计划项目(2012BAD12B07);甘肃省创新研究群体计划项目(1210RJIA006)

谭启东,男,硕士,主要从事兽医寄生虫病学及分子生物学方面研究

周东辉,E-mail:zhoudonghui@caas.cn