冠状动脉造影检查疑似冠心病患者6040例合并传统心血管病危险因素的临床分析

江立生 邵琴 卜军 何奔

·临床研究·

冠状动脉造影检查疑似冠心病患者6040例合并传统心血管病危险因素的临床分析

江立生邵琴卜军何奔

目的对临床上冠心病患者合并传统心血管病危险因素进行分析。方法纳入本中心2013年1月至2015年2月因冠心病或疑似冠心病行冠状动脉造影(CAG)检查的住院患者,将存在严重冠心病并接受经皮冠状动脉介入治疗(PCI)的患者归为PCI组(2808例),不存在严重冠心病且未行PCI/冠状动脉旁路移植术(CABG)的患者归为No-PCI/CABG组(3232例)。PCI组再分为急性ST段抬高心肌梗死(STEMI)组、非ST段抬高急性心肌梗死/不稳定型心绞痛(NSTEMI/UA)组和稳定型心绞痛(SA)组。对临床上合并的传统心血管病危险因素进行回顾性分析。结果(1)PCI组患者男性比例(75.4%比53.1%,P<0.0001)、平均年龄[(64.83±0.20)岁比(63.39±0.18)岁,P<0.0001]、高血压病(66.7%比54.7%,P<0.0001)、糖尿病/糖耐量异常(37.0%比20.8%,P<0.0001)、卒中(7.0%比5.4%,P=0.0098)和慢性肾病(4.3%比2.8%,P=0.001)比例显著高于No-PCI/CABG组;而两组间高脂血症的比例,差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。(2)PCI组中女性高血压病(74.1%比64.3%,P<0.0001)、糖尿病/糖耐量异常(42.5%比35.3%,P=0.0007)和卒中(9.4%比6.2%,P=0.0054)比例均显著高于男性,差异均有统计学意义;无论PCI组还是No-PCI/CABG组,女性高脂血症比例均显著高于男性。(3)对PCI组进行亚组分析发现,STEMI组男性比例显著高于NSTEMI/UA组和SA组(83.9%比72.9%比72.3%,P<0.0001),而发病年龄显著小于NSTEMI/UA组和SA组[(62.54±0.45)岁比(65.15±0.28)岁比(66.17±0.34)岁,P<0.0001]。SA组高血压病(71.9%比66.9%比60.0%,P<0.0001)和既往靶血管血运重建(PCI/CABG)(33.9%比18.7%比7.2%,P<0.0001)比例显著高于STEMI组和NSTEMI/UA组;NSTEMI/UA组糖尿病/糖耐量异常比例显著高于STEMI组和SA组(39.7%比35.1%比34.4%,P<0.0001),差异均有统计学意义;而高脂血症、慢性肾病和卒中的比例三亚组间差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。结论高血压病和糖尿病是冠心病最重要的危险因素,既往靶血管血运重建是SA和NSTEMI/UA患者靶血管再次血运重建的重要原因;行PCI的严重冠心病患者中,男性比例高于女性,但女性合并高血压病、糖尿病/糖耐量异常和卒中的比例高于男性。

冠心病;介入治疗;危险因素;回顾性分析

冠状动脉粥样硬化性心脏病(冠心病)仍然是全球范围内首屈一指的公共卫生问题。近年来,欧美等发达国家冠心病死亡率呈逐年下降趋势[1-2], 然而这种令人鼓舞的趋势在中国却并未出现,反而出现了更加严重的情况。根据《中国心血管病报告2014》数据,从2002年到2013年,中国冠心病和心肌梗死的死亡率仍逐年上升,2013年同2002年相比,中国农村和城市冠心病的死亡率分别增加了3.6倍和2.5倍,急性心肌梗死的死亡率分别增加了4倍和4.3倍,而且预测未来10年中国冠心病的发病率和死亡率仍然上升[3]。

影响冠心病发病和死亡的因素有很多种,除与经济状况、治疗方式、生活习惯及种族等有关外,也与高血压病、糖尿病、高脂血症等传统心血管病危险因素密切相关[4-6]。近年来,有研究报道显示,冠心病患者合并传统心血管病危险因素在部分东亚国家与欧美等西方国家相比存在一定差异[7-12]。在PLATO-ACS研究[7]中,亚裔患者并发糖尿病的比率高于非亚裔患者,而并发高脂血症的比率则低于非亚裔患者。换言之,与欧美等发达国家相比,近年来中国逐年升高的冠心病死亡率也可能与中国人合并心血管病危险因素情况及治疗水平与欧美等发达国家不同有关。

本研究针对本中心经冠状动脉造影(coronary angiography,CAG)证实存在严重阻塞性冠状动脉病变并接受经皮冠状动脉介入治疗(percutaneous coronary intervention,PCI)的冠心病患者和CAG检查结果正常或仅提示轻度病变的住院患者合并传统心血管病危险因素的状况进行回顾性分析,以明确不同严重程度的冠心病合并传统心血管病危险因素的状况,为科学管理冠心病危险因素和降低冠心病发病率、死亡率提供依据。

1 对象与方法

1.1研究对象

本研究以上海交通大学医学院附属仁济医院2013年1月至2015年2月住院行CAG检查的冠心病和疑似冠心病患者为研究对象。在总共6862例行CAG检查的患者中,2808例存在严重冠心病(冠状动脉狭窄≥75% 或50%<狭窄<75%但介入医师认为有PCI适应证)并接受PCI的患者作为PCI组;3232例CAG结果正常或不存在严重冠心病[冠状动脉正常,或存在狭窄<70%非左主干病变,或存在狭窄<50%左主干病变]且不需要行PCI或冠状动脉旁路移植术(coronary artery bypass grafting,CABG)的患者作为非PCI/CABG组(No-PCI/CABG组);不需要行PCI的822例患者因既往曾接受PCI或CABG,或存在严重冠状动脉病变接受CABG或药物保守治疗未纳入本研究。PCI组患者再根据临床类型分为急性ST段抬高心肌梗死(ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction,STEMI)组、非ST段抬高心肌梗死(non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction,NSTEMI)/不稳定型心绞痛(unstable angina,UA)组和稳定型心绞痛(stable angina, SA)组。研究中使用的传统心血管病危险因素和伴发疾病的诊断标准如下:(1)存在既往病史并正在接受相应药物治疗;(2)住院期间新发现的心血管病危险因素和伴发疾病根据我国现行诊疗指南进行诊断[13]。

1.2研究方法

对各组/亚组患者的年龄、性别等人口学数据,伴发的高血压病、糖尿病/糖耐量异常、高脂血症、慢性肾病、卒中等传统心血管病危险因素情况,以及PCI各亚组的住院期间死亡率、住院时间和住院费用进行回顾性分析和比较。

1.3统计学分析

2 结果

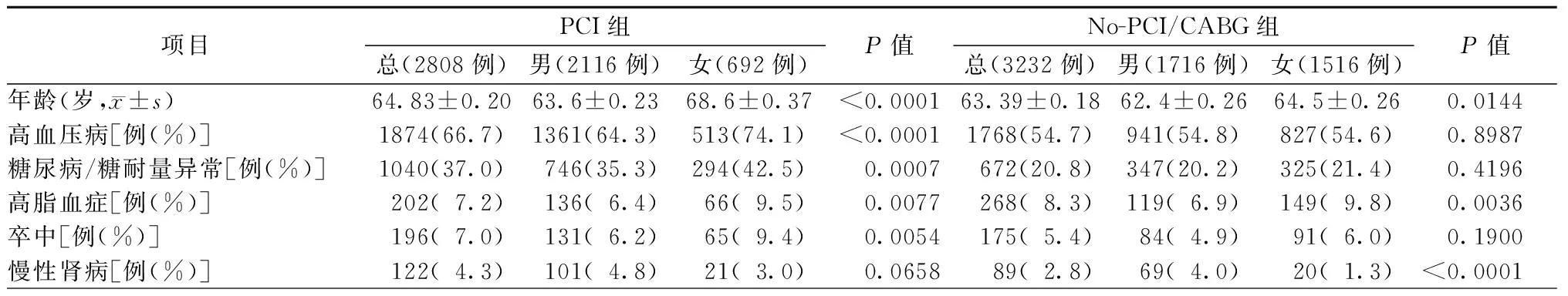

2.1PCI组和No-PCI/CABG组人口学资料和心血管病危险因素分析(表1)

PCI组患者男性比例[75.4%(2116/2808)比53.1%(1716/3232),P<0.0001]、平均年龄[(64.83±0.20)岁 比(63.39±0.18)岁,P<0.0001]均显著高于No-PCI/CABG组,差异均有统计学意义。无论PCI组还是No-PCI/CABG组,女性平均年龄均高于男性,分别为PCI组[(68.6±0.37)岁比(63.6±0.23)岁,P<0.0001]和No-PCI/CABG组[(64.5±0.26)岁比(62.4±0.26)岁,P=0.0144],差异均有统计学意义。

PCI组患者合并高血压病(66.7%比54.7%,P<0.0001)、糖尿病/糖耐量异常(37.0%比20.8%,P<0.0001)、卒中(7.0%比5.4%,P=0.0098)和慢性肾病(4.3%比2.8%,P=0.001)的比例均显著高于No-PCI/CABG组,差异均有统计学意义;而两组间高脂血症比较(7.2%比8.3%,P=0.2206),差异无统计学意义。在PCI组中,女性合并高血压病(74.1%比64.3%,P<0.0001)、糖尿病/糖耐量异常(42.5%比35.3%,P=0.0007)、高脂血症(9.5%比6.4%,P=0.0077)和卒中(9.4%比6.2%,P=0.0054)的比例均显著高于男性,差异均有统计学意义;在No-PCI/CABG组中女性高脂血症比例显著高于男性(9.8%比6.9%,P=0.0036),而慢性肾病比例显著低于男性(1.3%比4.0%,P<0.0001),差异均有统计学意义。

2.2PCI组中各亚组人口学资料和心血管病危险因素分析(表2)

亚组分析发现,STEMI组患者男性比例显著高于NSTEMI/UA组和SA组(83.9%比72.9%比72.3%,P<0.0001),而发病年龄则显著低于后两组[(62.54±0.45)岁比(65.15±0.28)岁比(66.17±0.34)岁,P<0.0001)],差异均有统计学意义;但NSTEMI/UA组和SA组两组间性别和发病年龄比较,差异均无统计学意义(均P>0.05)。在合并传统心血管病危险因素方面,SA组高血压病(71.9%比66.9%比60.0%,P<0.0001)和既往靶血管血运重建(PCI/CABG)(33.9%比18.7%比7.2%,P<0.0001)比例显著高于NSTEMI/UA组和STEMI组,NSTEMI/UA组也显著高于STEMI组(18.7%比7.2%,P<0.0001),差异均有统计学意义。NSTEMI/UA组糖尿病/糖耐量异常比例显著高于STEMI组和SA组(39.7%比35.1%比34.4%,P<0.0001),而STEMI组和SA组差异无统计学意义(35.1%比34.4%,P>0.05)。三亚组间合并高脂血症、慢性肾病和卒中的比例比较,差异均无统计学意义(均P>0.05)。STEMI患者平均住院时间[(11.14±0.22)d比(7.68±0.14)d比(6.65±0.14)d,P<0.0001]、住院费用[(60 812±980)元比(53 743±615)元比(50 461±788)元,P<0.0001]和住院期间死亡率(3.1%比0.2%比0,P<0.0001)均显著高于NSTEMI/UA组和SA组;NSTEMI/UA组平均住院时间[(7.68±0.14)d比(6.65±0.14)d,P<0.0001]、住院费用[(53 743±615)元比(50 461±788)元,P<0.001]也均显著高于SA组,差异均有统计学意义;但NSTEMI/UA组与SA组住院期间死亡率则差异无统计学意义。

表1 介入治疗患者同非介入治疗患者间传统心血管病危险因素的差别

注:PCI,经皮冠状动脉介入治疗;No-PCI,非经皮冠状动脉介入治疗;CABG,冠状动脉旁路移植

表2 PCI组患者亚组分析

注:STEMI,ST段抬高心肌梗死;NSTEMI,非ST段抬高心肌梗死;UA,不稳定型心绞痛;SA,稳定型心绞痛;PCI,经皮冠状动脉介入治疗;CABG,冠状动脉旁路移植术

3 讨论

本中心的临床结果分析显示,PCI组患者合并高血压病、糖尿病/糖耐量异常、卒中和慢性肾病的比例显著高于No-PCI/CABG组患者,这与国外研究结果相一致[7-9]。此外,本研究结果还显示,PCI组患者合并糖尿病/糖耐量异常的比例高于欧美等西方国家,而合并高脂血症的比例却显著低于欧美等西方国家,与No-PCI/CABG组患者相当[7-9]。日本及中国台湾等东亚国家和地区的研究结果与本研究也基本相一致[14-15],进一步表明东亚国家和地区的冠心病患者在合并传统心血管病危险因素方面与欧美国家存在一定差别。

对PCI组患者进行亚组分析发现,STEMI患者发病年龄低于NSTEMI/UA组和SA组患者,而住院时间、住院费用和住院期间死亡率均显著高于NSTEMI/UA组和SA组患者。本研究中住院期间死亡率与欧美发达国家相近甚至更低[16-17]。此外,本研究数据还显示,接受PCI的SA患者合并高血压病和既往靶血管血运重建(PCI/CABG)史的比例最高,而NSTEMI/UA患者合并糖尿病/糖耐量异常比例最高。然而,STEMI组、NSTEMI/UA组和SA组三亚组间在合并高脂血症、慢性肾病和卒中方面却差异无统计学意义。国外PL-ACS研究[18]和GRACE研究[9]也显示,NSTEMI/UA患者合并高血压病、糖尿病和既往靶血管血运重建的比例高于STEMI患者,这与本研究结果相一致。

近年来有较多研究显示,男、女性冠心病患者在合并传统心血管病危险因素和预后方面存在一定差异,女性患者合并高血压病、糖尿病、慢性肾病及高脂血症的比例高于男性[19-22],这可能是女性患者在预后方面比男性差的重要原因[23]。本研究结果也显示,接受PCI/CABG的冠心病患者中,女性合并高血压病、糖尿病/糖耐量异常和卒中的比例均高于男性,而未接受PCI/CABG的患者男、女间则差异无统计学意义,这与国外报道基本一致[24-25]。然而,两组患者中,女性合并高脂血症的比例均高于男性。

总之,高血压病和糖尿病是冠心病最重要的危险因素;由于PCI/CABG在冠心病治疗中的广泛应用,既往靶血管血运重建也成为SA和NSTEMI/UA患者靶血管再次血运重建的重要原因。需要接受PCI的严重冠心病患者在卒中发生率和传统心血管病危险因素方面存在性别差异,男性发生需要行PCI的严重冠心病比例高于女性,而女性合并高血压病、糖尿病/糖耐量异常和卒中的比例则高于男性。

[1] Ivanovic J. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2008 Update. Circulation, 2008, 117(4): e25-e146.

[2] National Institutes for Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Morbidity and Mortality: 2007 Chartbook on Cardiovascular, Lung, and Blood Disease. Available at http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/resources/docs/07-chtbk.pdf

[3] 陈伟伟,高润霖,刘力生,等.《中国心血管病报告2014》概要.中国循环杂志,2015,30(7):617-622.

[4] Canto JG, Kiefe CI, Rogers WJ, et al. Number of coronary heart disease risk factors and mortality in patients with first myocardial infarction. JAMA,2011,306(19):2120-2127.

[5] 姚远,梁峰,沈珠军.经皮冠状动脉介入治疗后冠心病心绞痛患者生存质量影响因素的分析.中国介入心脏病学杂志,2015,23(9):508-511.

[6] Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet, 2004,364(9438):937-952.

[7] Kang HJ, Clare RM, Gao R, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in Asian patients with acute coronary syndrome: A retrospective analysis from the Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial. Am Heart J, 2015,169(6): 899-905.e1.

[8] Owsiak M, Pelc-Nowicka A, Badacz L, et al. Increased prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with acute coronarysyndrome and indications for treatment with oral anticoagulation. Kardiologia Polska, 2011, 69(9): 907-912.

[9] Avezum A, Makdisse M, Spencer F, et al. Impact of age on management and outcome of acute coronary syndrome: observations from the global registry of acute coronary events (GRACE). Am Heart J, 2005, 149(1): 67-73.

[10] 刘军,赵冬,刘群,等.中国多省市急性冠状动脉综合征住院患者高胆固醇血症患病现况.中华心血管病杂志,2009,37(5):449-453.

[11] Hao K, Yasuda S, Takii T, et al.Urbanization, life style changes and the incidence/in-hospital mortality of acute myocardial infarction in Japan:report from the MIYAGI-AMI Registry Study. Circ J, 2012,76(5): 1136-1144.

[12] Yang HY, Huang JH, Hsu CY, et al. Gender differences and the trend in the acute myocardial infarction: a 10-year nationwide population-based analysis. SCI WORLD J, 2011, 2012(8):184075.

[13] 中华医学会心血管病学分会,中华心血管病杂志编辑委员会. 中国心血管病预防指南. 中华心血管病杂志, 2011, 39(1): 263-279.

[14] Nishiyama S, Watanabe T, Arimoto T, et al. Trends in coronary risk factors among patients with acute myocardial infarction over the last decade: the Yamagata AMI registry.J Atheroscler Thromb, 2010,17(9):989-998.

[15] Yayan J. Association of traditional risk factors with coronary artery disease in nonagenarians: the primary role of hypertension. Clin Interv Aging, 2014,9(9):2003-2012.

[16] Nallamothu BK, Normand SLT, Wang Y, et al. Relation between door-to-balloon times and mortality after primary percutaneous coronary intervention over time: a retrospective study. Lancet, 2015, 385(9973):1114-1122.

[17] Sugiyama T, Hasegawa K, Kobayashi Y, et al. Differential time trends of outcomes and costs of care for acute myocardial infarction hospitalizations by ST elevation and type of intervention in the United States, 2001-2011. J Am Heart Assoc, 2015, 4(3):e001445.

[18] Owsiak M, Pelc-Nowicka A, Badacz L, et al. Increased prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with acute coronary syndrome and indications for treatment with oral anticoagulation. Kardiol Pol, 2011,69(9):907-912.

[19] Nguyen HL, Ha DA, Phan DT, et al. Sex differences in clinical characteristics, hospital management practices, and in-hospital outcomes in patients hospitalized in a Vietnamese hospital with a first Aacute myocardial infarction. PLoS One, 2014,9(4): e95631.

[20] Roffi M, Radovanovic D, Erne P, et al. Gender-related mortality trends among diabetic patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: insights from a nationwide registry 1997-2010. Euro Heart J, 2013,2(4):342-349.

[21] Papakonstantinou NA, Stamou MI, Baikoussis NG, et al. Sex differentiation with regard to coronary artery disease. J Cardiol,2013,62(1):4-11.

[22] Kytö V, Sipilä J, Rautava P. Gender and in-hospital mortality of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (from a multihospital nationwide registry study of 31,689 patients).Am J Cardiol, 2015,115(3):303-306.

[23] Pancholy SB, Shantha GP, Patel T,et al. Sex differences in short-term and long-term all-cause mortality among patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated by primary percutaneous intervention: a meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med,2014,174(11):1822-1830.

[24] Mega JL, Hochman JS, Scirica BM,et al. Clinical features and outcomes of women with unstable ischemic heart disease: observations from metabolic efficiency with ranolazine for less ischemia in non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes-thrombolysis in myocardial infarction 36 (MERLIN-TIMI 36). Circulation, 2010,121(16):1809-1817.

[25] Kambara H, Yamazaki T, Hayashi D, et al. Gender differences in patients with coronary artery disease in Japan: the Japanese Coronary Artery Disease Study (the JCAD study). Circ J, 2009, 73(5):912-917.

Real world analysis of traditional cardiovascular risk factors in 6040 patients with suspected coronary heart disease undergoing angiography

JIANGLi-sheng,SHAOQin,BUJun,HEBen.

DepartmentofCardiology,RenjiHospital,SchoolofMedicine,ShanghaiJiaotongUniversity,Shanghai200127,China

ObjectiveTo analyze the real world status of traditional known cardiovascular risk factors in patients with coronary heart disease (CHD). Methods6040 in-hospital patients with CHD or suspected CHD undergoing angiography from 01/01/2013 to 02/28/2015 were retrospectively analyzed. According to angiography result, patients with severe coronary artery lesion and undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) were enrolled in the PCI group(n=2808) and patients without severe coronary artery lesion and not undergoing PCI or CABG were enrolled in the No-PCI/CABG group (n=3232). Patients in the PCI group were further divided into 3 subgroups which were STEMI group, NSTEMI/UA group and stable angina (SA) group. Results(1) Compared with the No-PCI/CABG group, patients in the PCI group have higher ratio of male patients (75.4%vs. 53.1%,P<0.0001), older average age (64.83±0.20vs. 63.39±0.18 years old,P<0.0001), and higher existing rates of traditional risk factors including hypertension (66.7%vs. 54.7%,P<0.0001), diabetes/impaired glucose tolerance (IGT)(37.0%vs. 20.8%,P<0.0001), stroke(7.0%vs. 5.4%,P=0.0098)and chronic kidney disease (CKD) (4.3%vs. 2.8%,P=0.001), but there was no statistic difference in existing rates of dyslipidemia between the two groups. (2)In the PCI group,female patients had higher prevalence of hypertension (74.1%vs. 64.3%,P<0.001), diabetes/IGT (42.5%vs. 35.3%,P=0.0007) and stroke (9.4%vs. 6.2%,P=0.0054) than the male patients. There were no significant sex difference in these comorbidities as above in No-PCI/CABG group. Female patients had higher prevalence of dyslipidemia than male patients in both PCI and No-PCI/CABG groups. (3) Among all the 3 PCI subgroups, STEMI patients presented with youngest average age(62.54±0.45vs. 65.15±0.28vs. 66.17±0.34 years old,P<0.0001) and highest male patient ratio (83.9%vs. 72.9%vs. 72.3%,P<0.0001). Patients in the SA subgroup had the highest prevalence of hypertension and prior revascularization including PCI and CABG. Patients in the NSTEMI/UA subgroup had the highest rates of diabetes/IGT. No significant differences were observed in the prevalence of dyslipidemia, CKD and stroke among all the subgroups.ConclusionsHypertension and diabetes are the leading risk factors of coronary artery disease, and prior revascularization is also an important cause of stable angina and NSTEMI/UA undergoing PCI. Patients requiring PCI were found to be more of male gendor, but female patients has higher prevalence of traditional cardiovascular risk factors including hypertension, diabetes/IGT or stroke than male patients.

Coronary heart disease;Percutaneous coronary intervention;Risk factors; Retrospective analysis

10.3969/j.issn.1004-8812.2016.09.004

200127上海,上海交通大学医学院附属仁济医院心内科

R541.4

2016-05-29)