早产与儿童急性白血病发生风险的Meta分析

黄艳 马倩倩 黄启涛 钟梅 周琳 佘秋敏 胡佳 梁小珍

早产是一个全球突出的公共健康问题,也是新生儿发病和死亡最常见的原因之一[1]。由于新生儿护理技术,包括产前糖皮质激素和表面活性剂的应用以及高频通气的进步,使早产儿存活数量得到了前所未有的提高[2]。目前,早产已被确认为多个非传染性疾病发生的危险因素之一。越来越多证据表明,早产儿在其今后成长过程中,出现糖尿病、心血管疾病、呼吸系统疾病以及神经和精神疾病的风险较正常儿童大大增加[3-7]。急性白血病是儿童最常见的癌症,但其病因还未完全阐明[8- 9]。近来研究表明,各种围产期因素,如产前父母吸烟以及胎儿早产可能会增加儿童白血病的发生风险[10-11]。由于早产儿成活率的提高,早产对儿童长远期健康的影响及其因果关系更值得关注。虽然早产和部分非传染性疾病(如哮喘、I型糖尿病等)之间的关联已经非常明确,但早产和儿童急性白血病发生风险的相关性尚未明确[12-24]。例如,部分研究表明,早产儿与对照组相比,结果显示急性白血病的发病率提高,而一些研究未能证明早产和儿童急性白血病发生风险的相关性。这种差异可能来源于每个单独研究中样本大小的不同。由于早产和儿童急性白血病发生风险之间的相关性还未明确,所以本研究系统回顾了目前的文献进行Meta分析,探讨早产与儿童急性白血病发生风险的相关性。

资料与方法

一、纳入与排除标准

纳入标准:(1)研究类型:病例对照研究、队列研究和横截面研究;(2)研究对象: 儿童,且经临床诊断为急性白血病的儿童患者; (3)暴露因素:早产;(4)结局指标: 早产儿在儿童期是否诊断为急性白血病。排除标准:(1)无对照组;(2)没有匹配的队列;(3)没有报告白血病发病率;(4)病例和病例报告。

二、文献检索

计算机检索PubMed、Web of Science 和 Embase等数据库并辅以文献追溯、手工检索等方法,收集建库至2015年12月国内外公开发表的关于早产和儿童急性白血病发生风险研究的文献,同时通过文献追溯法查找可能符合要求的研究。英文检索词包括preterm、acute lymphoblastic leukemia、acute myeloid leukemia、children。中文检索词包括早产、急性淋巴细胞白血病、急性髓系白血病、白血病、癌症、儿童。以PubMed为例,其具体检索策略见图1。

图1 PUbMed 检索策略

三、文献筛选、资料提取和纳入研究的偏倚风险评价

由2位研究者独立筛选文献、提取资料和评价纳入研究的偏倚风险,如遇分歧,通过讨论解决或咨询第三方协助判断。采用事先制定的资料提取表提取资料,主要提取内容包括:(1)纳入研究的基本信息,包括第一作者的姓氏、出版年、国籍等;(2)研究对象的基本特征,包括样本量、研究人群的年龄分布、病例编码、调整的混杂因素;(3)研究设计类型和质量评价的关键因素;(4)干预措施的具体细节;(5)研究关注的结局指标和结果测量数据。

四、纳入研究的方法学质量评价

纳入研究的偏倚风险采用Cochrane手册5.0 版针对RCT的偏倚风险评估工具进行评价。队列研究的偏倚风险采用(NOS)[25]评分表(Newcastle-Ottawa Scale)进行评价。

五、统计学方法

采用Stata 10.0和RevMan 5.3软件进行Meta分析。依据OR值及其95%CI评估早产和儿童急性白血病发生风险的相关性,纳入研究结果间的异质性分析采用 χ2检验(检验水准为α=0.1),并结合I2定量判断异质性的大小[26]。P<0.10 或I2>50%认为异质性有显著的统计学意义,可采用随机效应模型进行合并分析。若不存在异质性或异质性较小,可采用固定效应模型进行数据合并。采用漏斗图的对称性初步判断发表偏移,并采用Egger’s线性回归法进一步评估漏斗图的对称性[27]。对于计数资料计算OR值及其95%CI,P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

结 果

一、文献检索结果

初检共获得相关文献1 596篇,经逐层筛选后,最终纳入文献共12篇[12-23],共计2 786 687 名参与者,13 319名病例。 文献筛选流程及结果见图2。

图2 文献筛选流程及结果

二、纳入研究的基本特征和偏倚风险评价结果

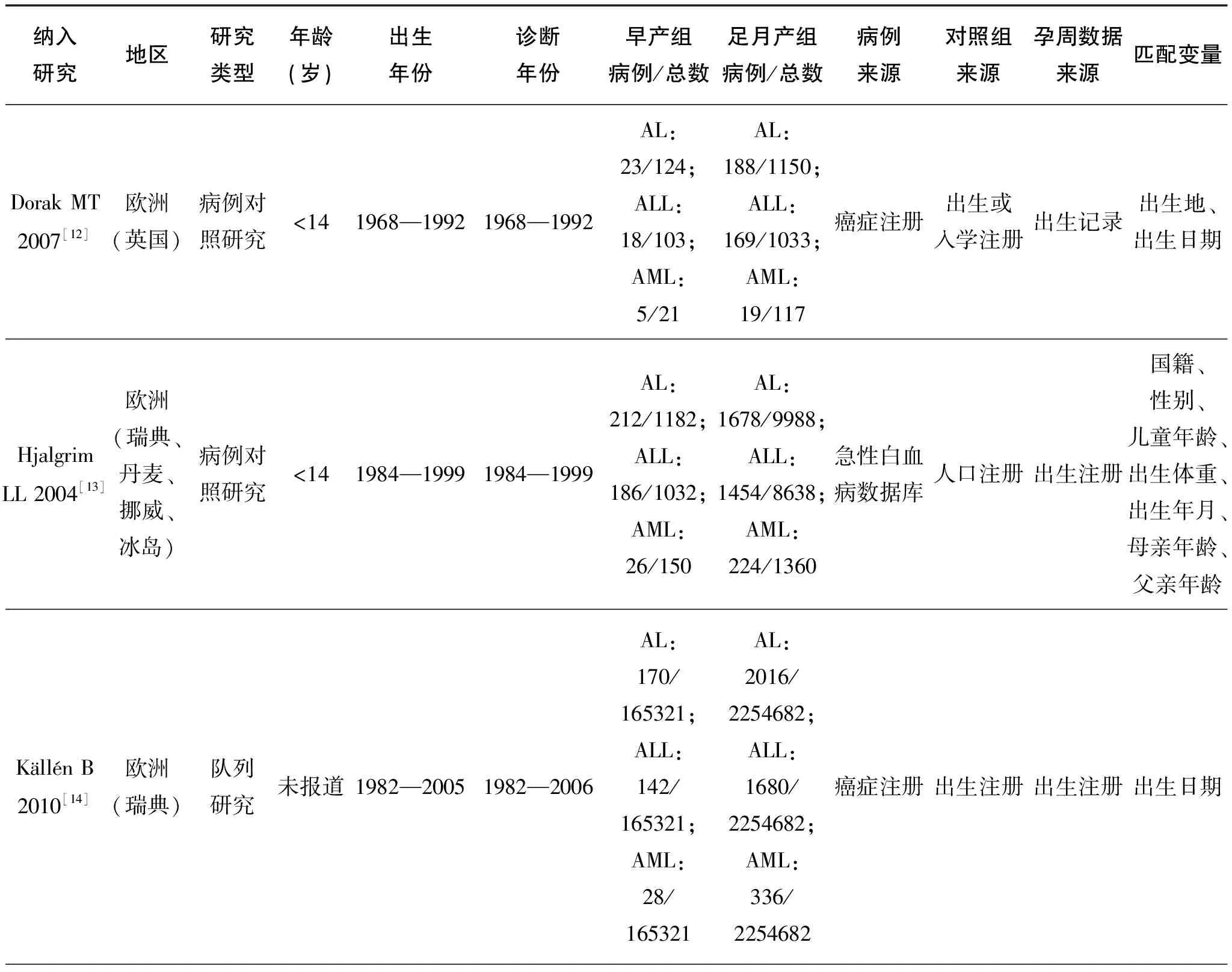

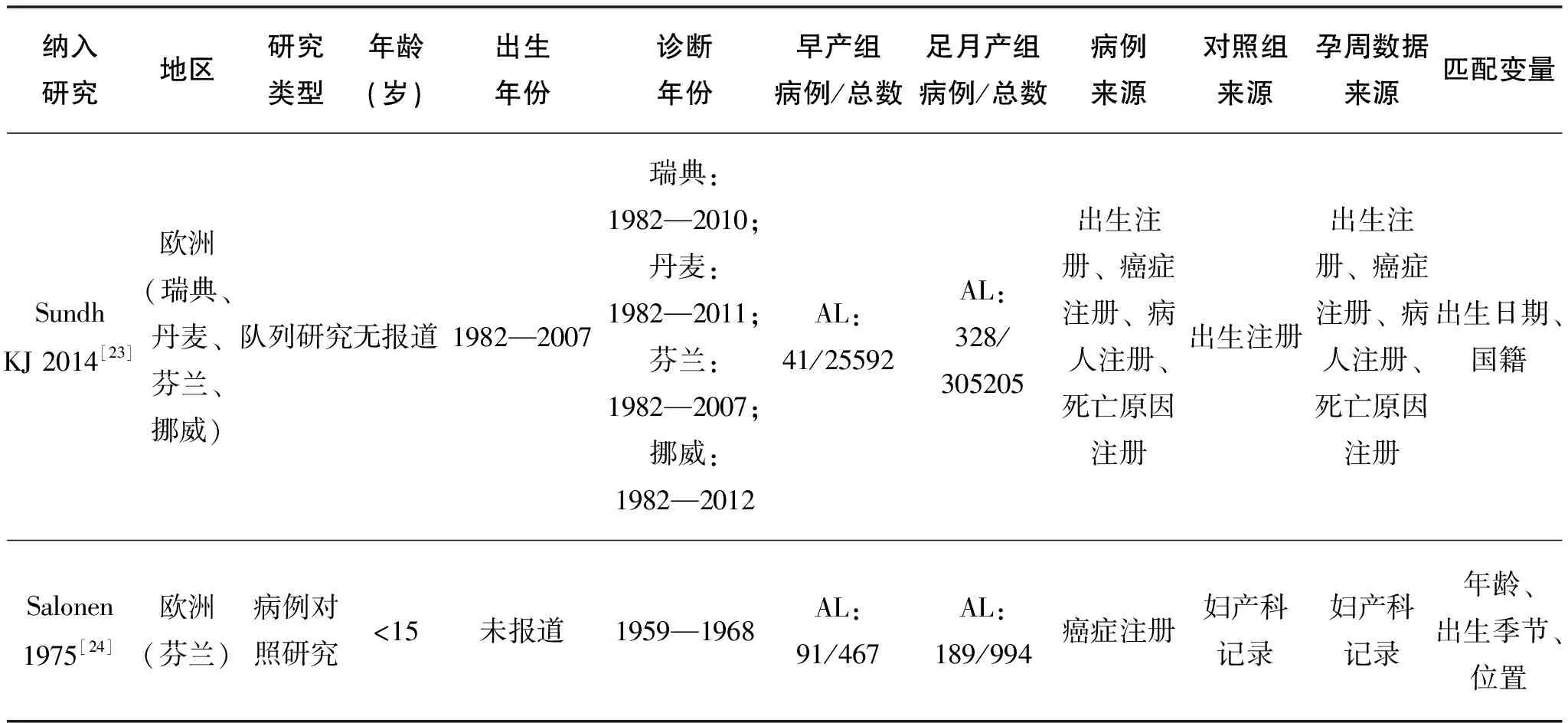

纳入研究的基本特征见表 1,偏倚风险评价结果见表 2。

表1 纳入研究的基本特征

(续表)

纳入研究地区研究类型年龄(岁)出生年份诊断年份早产组病例/总数足月产组病例/总数病例来源对照组来源孕周数据来源匹配变量McLaughlinCC 2006[15]北美(美国)病例对照研究<=9(一个月内除外)1978—20011985—2001AL:130/1264;ALL:109/1243;AML:21/1155AL:729/7234;ALL:628/7133;AML:101/6606癌症注册出生档案出生证明出生日期、母亲年龄、出生体重、性别、孕周、种族特点Okcu MF2002[16]北美(美国)病例对照研究<5未报道1995AL:3/207;ALL:3/207;AML:0/204AL:96/2511;ALL:78/2492;AML:19/2433癌症注册出生档案出生证明儿童年龄、母亲年龄、吸烟史OksuzyanS 2012[17]北美(美国)病例对照研究<151986—20071988—2008AL:586/1114;ALL:466/907;AML:120/207AL:4248/8507;ALL:3629/7231;AML:619/1276癌症注册出生注册出生记录儿童年龄、性别PodvinD 2006[18]北美(美国)病例对照研究<201980—20021981—2003AL:42/479AL:508/5561癌症注册癌症监督系统出生证明出生证明出生日期、母亲年龄ReynoldsR 2002[19]北美(美国)队列研究<51987—19971988—1997AL:129/395AL:1058/3187癌症注册出生注册出生证明出生日期、性别SavitzDA 1994[20]北美(美国)病例对照研究<15未报道1976—1983ALL:4/16ALL:50/205拨号调查拨号调查拨号调查性别、年龄、吸烟史、诊断年龄Silva NJ2004[21]欧洲(法国)病例对照研究<151990—1995—1998AL:46/136;ALL:41/86;AML:5/50AL:45/448;ALL:300/748;AML:45/493国家儿童白血病和淋巴瘤注册调查问卷调查问卷性别、年龄、位置SpectorLG 2007[22]北美(美国)病例对照研究<1未报道1996—2002AL:12/32AL:228/463儿童肿瘤组数据库拨号调查拨号调查出生日期、出生体重

(续表)

纳入研究地区研究类型年龄(岁)出生年份诊断年份早产组病例/总数足月产组病例/总数病例来源对照组来源孕周数据来源匹配变量SundhKJ 2014[23]欧洲(瑞典、丹麦、芬兰、挪威)队列研究无报道1982—2007瑞典:1982—2010;丹麦:1982—2011;芬兰:1982—2007;挪威:1982—2012AL:41/25592AL:328/305205出生注册、癌症注册、病人注册、死亡原因注册出生注册出生注册、癌症注册、病人注册、死亡原因注册出生日期、国籍Salonen1975[24]欧洲(芬兰)病例对照研究<15未报道1959—1968AL:91/467AL:189/994癌症注册妇产科记录妇产科记录年龄、出生季节、位置

注:AL: 急性白血病;ALL: 急性淋巴细胞白血病;AML: 急性髓系白血病。

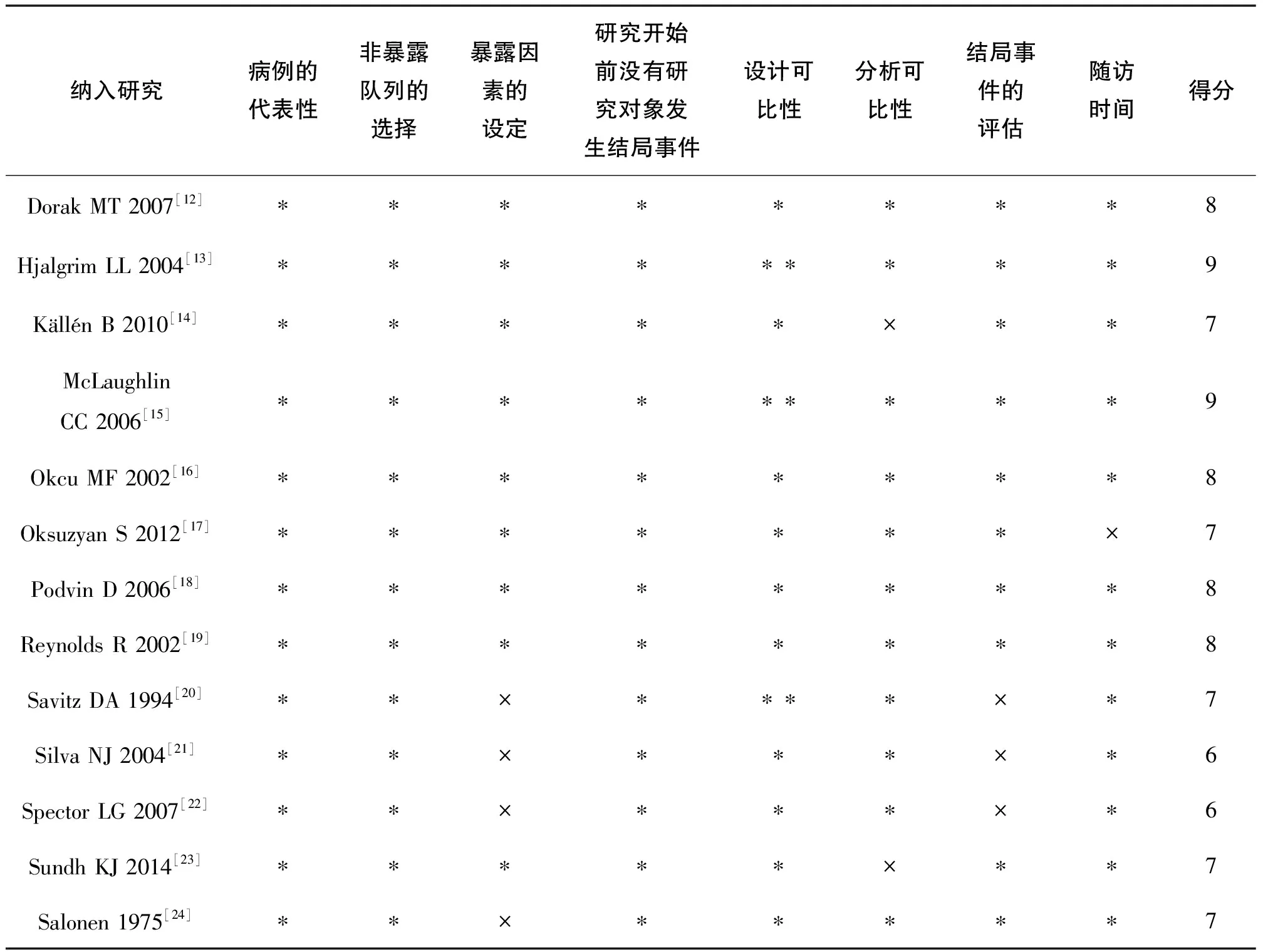

表2 纳入研究的偏倚风险评价结果

* ,该特征存在。×,该特征不存在。设计可比性的得分可分为0分(×)、1分(*)和最高得分2分(**)。

三、Meta分析结果

1.儿童急性白血病:本研究共纳入儿童急性白血病相关文献12篇,2 786 687 名参与者, 13 319 名病例[12-23]。Meta分析表明,与足月顺产相比,早产与儿童急性白血病发生风险有显著相关性(OR=1.09, 95%CI=1.02-1.17)和轻度异质性(I2=12.0%,P=0.33)(图2)。

2.急性淋巴细胞白血病:共纳入有关ALL的文献8篇,2 447 691名参与者, 9 237 名病例[12-17, 20-21]。结果显示,与足月顺产相比,早产与ALL发生风险没有显著相关性(OR=1.04, 95%CI=0.96-1.13),也没有异质性(I2=0.0 %,P=0.77)(图3)。

3.急性髓系白血病:共纳入AML相关文献7篇,2 432 599 名参与者,1 413 名病例[12-17, 21]。结果表明,与足月顺产相比,早产与AML发生风险有显著相关性(OR=1.42, 95%CI=1.21-1.67),但没有异质性 (I2=0.0%,P=0.49)(图4)。

4.亚组分类情况及结果: (1)研究类型 (AL: 队列研究或 病例对照研究[12-13, 15-18, 20-22, 24]; ALL: 队列研究[14]或病例对照研究[12, 13, 15-17, 20-21]; AML: 队列研究[14]或 病例对照研究[12-13, 15-17, 21]);(2)研究位置(AL: 欧洲[12-14, 21, 23-24]或 北美[15-20, 22]; ALL: 欧洲[12-14, 21]或 北美[15-17, 20]; AML: 欧洲[12-14, 21]或 北美[15-17]);(3)儿童性别 (AL: 混合[13, 17, 19-21],在男孩高[12, 15-16, 18, 23-24],在女孩高[22],或 不明确[14]; ALL: 混合[12, 17, 20-21],在男孩高[12, 15-16],在女孩高,或 不明确[14]; AML: 混合[13, 17, 21],在男孩高[12, 15-16],在女孩高,或 不明确[14]);(4)儿童白血病诊断的年龄(AL:<5 岁[12, 15-19, 21-22]或 不明确[13-14, 20, 23-24];ALL:<5 岁[12, 15-17, 21]或 不明确[13-14, 20]; AML:<5 岁[12, 15-17, 21]或 不明确[13-14]) ;(5)胎龄数据的来源(AL: 注册或记录[12-19, 23-24]或 拨号或问卷调查[1, 2, 4-7, 9-11, 13]; ALL: 注册或记录[12-17]或 拨号或问卷调查[20-21];;AML: 注册或记录[12-17]或 拨号或问卷调查[21])。汇总结果见表3。

表3 早产与白血病亚组分析结果

注:AL: 急性白血病;ALL: 急性淋巴细胞白血病;AML: 急性髓系白血病。大数据显示P<0.05。

讨 论

许多研究表明,早产儿童在其今后成长生活中,发生糖尿病、心血管疾病、呼吸系统疾病以及神经和精神疾病的风险增加[3-7],但是早产和儿童急性白血病发生风险的研究仍没有明确的定论。鉴于早产患儿的生存率越来越高[28],早产和儿童白血病之间任何潜在的因果关系都可能对公共健康问题产生深远的影响。本研究分析表明,早产与儿童急性白血病发生风险显著相关。此外亚组分析进一步证实了早产和AML之间的正相关关系,但在早产与ALL发生风险之间没有观察到显著的关联。

我们推测早产和儿童AML之间关联可能的生物学解释。首先,儿童白血病是免疫系统的癌症。因此,在儿童时期免疫发育异常或免疫系统功能障碍可能在白血病的发病中起了至关重要的作用[29- 30]。越来越多的研究表明,早产增加了儿童发生免疫相关疾病(如过敏,哮喘以及Ⅰ型糖尿病等)的风险[3, 31-32]。其次,由于婴儿早产通常具有低出生体重,以前的荟萃分析研究评估了白血病及其亚型(ALL和AML)与低和高出生体重的关联[11]。其结果表明,高出生体重增加了AL和ALL的发生风险,而AML的发生风险在低和高出生体重中都有增加,呈现“U形”相关关系。低出生体重和白血病发生风险的相关性的假设是基于2项证据:(1)胰岛素样生长因子(insulin-like growth factor, IGFs)与胎儿生长发育的许多方面呈显著正相关;(2)IGFs在肿瘤发生中起重要作用[10, 33-39]。之前的实验研究表明,IGF-1可促进淋巴和骨髓细胞的生长[40]。此外,过度的IGF-2增加了AML和ALL的发生风险[41-42]。虽然早产儿在子宫中可能不会出现IGF的过度刺激,但其出生后,由于早产儿的追赶性增长可导致IGF的过量[43-44]。之前的研究文献也支持我们的假设,它表明早产儿比足月婴儿产生更多的IGF-2并且尿量也显著增加,并提出IGF-2的持续抬高可能是由于早产儿的追赶性增长[45]。最近的研究也提示血清IGF-1的水平与早产儿早期加速增长密切相关[46- 47]。此外,Kistner的研究发现早产儿直到9岁时体内IGF-1的浓度依旧比同龄人更高[48]。

本次Meta分析是研究早产和儿童白血病发生风险相关性的一个全面系统的回顾。它有一定的优势:(1)大量的参与者和病例数量保证了统计资料和结论的可靠性。(2)研究结果为研究早产与儿童白血病发生风险相关性提供了一个良好估计。本研究没有发表偏倚,而且异质性也很低,可以提供更高的参考价值。(3)研究结果可以避免回忆偏倚,因为依据所有的注册表或记录,测量胎龄的亚组分析也证明早产与AL和AML发生风险有显著的关联。

本Meta分析的局限性:(1)纳入的研究主要是在美国和欧洲完成的,因此结论可能不适合应用于其他国家或种族。(2)虽然研究结果表明,早产儿在5岁以下发生AML的风险最高,但是不同的年龄与儿童急性白血病发生风险相关性差异比较大。例如,一些研究在目前的研究中包含了从0到16岁的病例,但是没有详细信息。因此无法进行更精确的分析,来评估早产和白血病的特定年龄范围的发生风险之间的相关性。(3)只有少数研究记录了极为早产的婴幼儿(<28孕周)发生儿童白血病的发病率,无法明确极早的孕周与儿童白血病发生风险的相关性。(4)另外,由于研究对象的地区、诊断时间、发病年龄等临床异质性性较高,我们对此进行了亚组分析。尽管结果提示不同地区早产儿发生白血病类型存在差异。并且年龄<5岁发生AML的风险更高。但其机制及可能的生物学解释尚不明确,需要更多的基础实验及大样本前瞻性队列研究进一步明确。

综上所述,本研究分析表明,早产是儿童白血病特别是AML发生风险危险因素之一。加强孕妇保健,延长孕周,降低早产发生率,对于儿童长远期健康有重大意义。

[1]Blencowe H, Cousens S, Oestergaard MZ, et al.National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: a systematic analysis and implications [J].Lancet, 2012,379(9832):2162-2172.

[2]Crump C.Medical history taking in adults should include questions about preterm birth [J].BMJ, 2014,349:g4860.

[3]Li S,Zhang M, Tian H,et al.Preterm birth and risk of type 1 and type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis [J].Obes Rev, 2014,15(10):804-811.

[4]Li S, Xi B.Preterm birth is associated with risk of essential hypertension in later life [J].Int J Cardiol, 2014,172(2):e361-e363.

[5]Parkinson JR, Hyde MJ, Gale C, et al.Preterm birth and the metabolic syndrome in adult life: a systematic review and meta-analysis [J].Pediatrics, 2013,131(4):e1240-e1263.

[6]Burnett AC, Anderson PJ, Cheong J, et al.Prevalence of psychiatric diagnoses in preterm and full-term children, adolescents and young adults: a meta-analysis [J].Psychol Med, 2011,41(12):2463-2474.

[7]Been JV, Lugtenberg MJ, Smets E, et al.Preterm birth and childhood wheezing disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis [J].PLoS Med, 2014,11(1):e1001596.

[8]Puumala SE, Ross JA, Aplenc R, et al.Epidemiology of childhood acute myeloid leukemia [J].Pediatr Blood Cancer, 2013,60(5):728-733.

[9]Wiemels J.Perspectives on the causes of childhood leukemia [J].Chem Biol Interact, 2012,196(3):59-67.

[10]Milne E, Greenop KR, Scott RJ, et al.Parental prenatal smoking and risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia [J].Am J Epidemiol, 2012,175(1):43-53.

[11]Caughey RW, Michels KB.Birth weight and childhood leukemia: a meta-analysis and review of the current evidence [J].Int J Cancer, 2009,124(11):2658-2670.

[12]Dorak MT, Pearce MS, Hammal DM, et al.Examination of gender effect in birth weight and miscarriage associations with childhood cancer (United Kingdom) [J].Cancer Causes Control, 2007,18(2):219-228.

[13]Hjalgrim LL, Rostgaard K, Hjalgrim H, et al.Birth weight and risk for childhood leukemia in Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Iceland [J].J Natl Cancer Inst, 2004,96(20):1549-1556.

[14]Kallen B, Finnstrom O, Lindam A, et al.Cancer risk in children and young adults conceived by in vitro fertilization [J].Pediatrics, 2010,126(2):270-276.

[15]McLaughlin CC, Baptiste MS, Schymura MJ, et al.Birth weight, maternal weight and childhood leukaemia [J].Br J Cancer, 2006,94(11):1738-1744.

[16]Okcu MF, Goodman KJ, Carozza SE, et al.Birth weight, ethnicity, and occurrence of cancer in children: a population-based, incident case-control study in the State of Texas, USA [J].Cancer Causes Control, 2002,13(7):595-602.

[17]Oksuzyan S, Crespi CM, Cockburn M, et al.Birth weight and other perinatal characteristics and childhood leukemia in California J].Cancer Epidemiol, 2012,36(6):e359-e365.

[18]Podvin D, Kuehn CM, Mueller BA, et al.Maternal and birth characteristics in relation to childhood leukaemia [J].Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol, 2006,20(4):312-322.

[19]Reynolds P, Von Behren J, Elkin EP.Birth characteristics and leukemia in young children [J].Am J Epidemiol, 2002,155(7):603-613.

[20]Savitz DA, Ananth CV.Birth characteristics of childhood cancer cases, controls, and their siblings [J].Pediatr Hematol Oncol, 1994,11(6):587-599.

[21]Jourdan-Da SN, Perel Y, Mechinaud F, et al.Infectious diseases in the first year of life, perinatal characteristics and childhood acute leukaemia [J].Br J Cancer, 2004,90(1):139-145.

[22]Spector LG, Davies SM, Robison LL, et al.Birth characteristics, maternal reproductive history, and the risk of infant leukemia: a report from the Children's Oncology Group [J].Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2007,16(1):128-134.

[23]Sundh KJ, Henningsen AK, Kallen K, et al.Cancer in children and young adults born after assisted reproductive technology: a Nordic cohort study from the Committee of Nordic ART and Safety (CoNARTaS) [J].Hum Reprod, 2014,29(9):2050-2057.

[24]Salonen T, Saxen L.Risk indicators in childhood malignancies [J].Int J Cancer, 1975,15(6):941-946.

[25]Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al.The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration [J].Ann Intern Med, 2009,151(4):W65-W94.

[26]Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al.Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses [J].BMJ, 2003,327(7414):557-560.

[27]Egger M, Smith GD.Bias in location and selection of studies [J].BMJ, 1998,316(7124):61-66.

[28]Morken NH.Preterm birth: new data on a global health priority [J].Lancet, 2012,379(9832):2128-2130.

[29]Lion E, Willemen Y, Berneman ZN, et al.Natural killer cell immune escape in acute myeloid leukemia [J].Leukemia, 2012,26(9):2019-2026.

[30]Campos-Sanchez E, Toboso-Navasa A, Romero-Camarero I, et al.Acute lymphoblastic leukemia and developmental biology: a crucial interrelationship [J].Cell Cycle, 2011,10(20):3473-3486.

[31]Jaakkola JJ, Ahmed P, Ieromnimon A, et al.Preterm delivery and asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis [J].J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2006,118(4):823-830.

[32]Buske-Kirschbaum A, Krieger S, Wilkes C, et al.Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function and the cellular immune response in former preterm children [J].J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2007,92(9):3429-3435.

[33]Milne E, Greenop KR, Metayer C, et al.Fetal growth and childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: findings from the childhood leukemia international consortium [J].Int J Cancer, 2013,133(12):2968-2979.

[34]Papadopoulou C, Antonopoulos CN, Sergentanis TN, et al.Is birth weight associated with childhood lymphoma? A meta-analysis [J].Int J Cancer, 2012,130(1):179-189.

[35]Harder T, Plagemann A, Harder A.Birth weight and subsequent risk of childhood primary brain tumors: a meta-analysis [J].Am J Epidemiol, 2008,168(4):366-373.

[36]Cao H, Wang G, Meng L, et al.Association between circulating levels of IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 and lung cancer risk: a meta-analysis [J].PLoS One, 2012,7(11):e49884.

[37]Chen W, Wang S, Tian T, et al.Phenotypes and genotypes of insulin-like growth factor 1, IGF-binding protein-3 and cancer risk: evidence from 96 studies [J].Eur J Hum Genet, 2009,17(12):1668-1675.

[38]Elhddad AS, Lashen H.Fetal growth in relation to maternal and fetal IGF-axes: a systematic review and meta-analysis [J].Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand, 2013,92(9):997-1006.

[39]Agrogiannis GD, Sifakis S, Patsouris ES, et al.Insulin-like growth factors in embryonic and fetal growth and skeletal development (Review) [J].Mol Med Rep, 2014,10(2):579-584.

[40]Alpdogan O, Muriglan SJ, Kappel BJ, et al.Insulin-like growth factor-I enhances lymphoid and myeloid reconstitution after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation [J].Transplantation, 2003,75(12):1977-1983.

[41]Wu HK, Weksberg R, Minden MD, et al.Loss of imprinting of human insulin-like growth factor II gene, IGF2, in acute myeloid leukemia [J].Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 1997,231(2):466-472.

[42]Vorwerk P, Wex H, Bessert C, et al.Loss of imprinting of IGF-II gene in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia [J].Leuk Res, 2003,27(9):807-812.

[43]Tinnion R, Gillone J, Cheetham T, et al.Preterm birth and subsequent insulin sensitivity: a systematic review [J].Arch Dis Child, 2014,99(4):362-368.

[44]Hansen-Pupp I, Lofqvist C, Polberger S, et al.Influence of insulin-like growth factor I and nutrition during phases of postnatal growth in very preterm infants [J].Pediatr Res, 2011,69(5 Pt 1):448-453.

[45]Quattrin T, Albini CH, Sportsman C, et al.Urinary insulin-like growth factor-II excretion in healthy infants and children with normal and abnormal growth [J].Pediatr Res, 1993,34(4):435-438.

[46]van de Lagemaat M, Rotteveel J, Heijboer AC, et al.Growth in preterm infants until six months postterm: the role of insulin and IGF-I [J].Horm Res Paediatr, 2013,80(2):92-99.

[47]Hansen-Pupp I, Hovel H, Lofqvist C, et al.Circulatory insulin-like growth factor-I and brain volumes in relation to neurodevelopmental outcome in very preterm infants.Pediatr Res, 2013,74(5):564-569.

[48]Kistner A, Deschmann E, Legnevall L, et al.Preterm born 9-year-olds have elevated IGF-1 and low prolactin, but levels vary with behavioural and eating disorders [J].Acta Paediatr, 2014,103(11):1198-1205.