Healthcare waste management in selected government and private hospitals in Southeast Nigeria

Healthcare waste management in selected government and private hospitals in Southeast Nigeria

Tel: +234 8056306927

E-mail: a.n.oli@live.com

Peer review under responsibility of Hainan Medical University.

Angus Nnamdi Oli1*, Callistus Chibuike Ekejindu1, David Ufuoma Adje2, Ifeanyi Ezeobi3,

Obiora Shedrack Ejiofor4, Christian Chibuzo Ibeh5, Chika Flourence Ubajaka51Department of Pharmaceutical Microbiology and Biotechnology, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Nnamdi Azikiwe

University, Agulu Campus, Anambra State, Nigeria

2Department of Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacy Administration, Faculty of Pharmacy, Delta State University, Abraka,

Nigeria

3Department of Surgery, Anambra State University Teaching Hospital, Amaku Awka, Anambra State, Nigeria

4Department of Pediatrics, Anambra State University Teaching Hospital, Amaku Awka, Anambra State, Nigeria

5Department of Community Medicine, College of Health Sciences, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Nnewi Campus, Anambra State, Nigeria

ARTICLE INFO

Article history:

Received 24 Jun 2015

Receivedinrevisedform12 Aug,2nd revised form 17 Aug 2015

Accepted 20 Sep 2015

Available online 10 Nov 2015

Keywords:

Healthcare waste

Waste disposal system

Government

Private hospitals

South-east

Nigeria

ABSTRACT

Objective: To assess healthcare workers' involvement in healthcare waste management in public and private hospitals.

Methods: Validated questionnaires (n = 660) were administered to randomly selected healthcare workers from selected private hospitals between April and July 2013.

Results: Among the healthcare workers that participated in the study, 187 (28.33%) were medical doctors, 44 (6.67%) were pharmacists, 77 (11.67%) were medical laboratory scientist,35(5.30%)werewastehandlersand317(48.03%)werenurses.Generally,thenumber of workers that have heard about healthcare waste disposal system was above average 424 (69.5%). More health-workers in the government (81.5%) than in private (57.3%) hospitals were aware of healthcare waste disposal system and more in government hospitals attended training on it. The level of waste generated by the two hospitals differed significantly (P = 0.0086) with the generation level higher in government than private hospitals. The materials for healthcare waste disposal were significantly more available (P = 0.001) in government than private hospitals. There was no significant difference (P = 0.285) in syringes and needles disposal practices in the two hospitals and they were exposed to equal risks(P=0.8510).Fifty-six(18.5%)and140(45.5%)ofthestudyparticipantsinprivateand government hospitals respectively were aware of the existence of healthcare waste management committeewith134(44.4%) and 19(6.2%)workers confirmingthat itdidnotexist in their institutions. The existence of the committee was very low in the private hospitals.

Conclusions: The availability of material for waste segregation at point of generation, compliance of healthcare workers to healthcare waste management guidelines and the existence of infection control committee in both hospitals is generally low and unsatisfactory.

1. Introduction

Healthcare activities, although protect and restore health as well as save lives, generate a lot of wastes and by-products that can impact on both health and environment[1]. Healthcare waste is a by-product of healthcare that includes sharps, non-sharps, blood, body parts, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, medical devices and radioactive materials [2]. Of the total amount of wastegenerated by health-care activities, about 80% is general waste. The remaining 20% is considered as hazardous material that may be infectious, toxic or radioactive [3]. Every year, an estimated 16000 million injections are administered worldwide, but not all of the needles and syringes are properly disposed of afterward. Health-care waste contains potentially harmful microorganisms which can infect hospital patients, health-care workers and the general public.

When hazardous health care wastes are not properly managed, exposure to them could lead to infections, infertility, genital deformities, hormonally triggered cancers, mutagenicity, dermatitis, asthma and neurological disorders in children; typhoid, cholera, hepatitis, AIDS and other viral infections through sharps contaminated with blood [1,4]. The people at risk of healthcare hazardous waste include healthcare workers, patients, visitors to healthcare establishments, workers in support services, workers in waste disposal facilities, fetuses in the wombs of mothers, members of public and scavengers [2,5]. Unfortunately, the adverse effects of healthcare hazardous wastes are usually not attributed to them unless a careful and thorough investigation is carried out. Improper handling of solid waste in the hospital may increase the airborne pathogenic bacteria, which could adversely affect the hospital environment and community at large. Improper medical management has serious impact on human environment. Apart from risk of water, air and soil pollution, it hasconsiderableimpactonhumanhealthduetoestheticeffects[6].

The hazard in a healthcare setting includes exposure to blood, saliva, or other body fluids or aerosols that may carry infectious materials such as hepatitis C, HIV or other blood-borne or body fluid pathogens [7].

This research is a comparative study on healthcare waste management in selected public and private hospitals in Southeast Nigeria.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study participants

A total of 1000 healthcare workers, belonging to different fields, were administered validated questionnaires out of which 660questionnaireswererecovered.Theinclusioncriteriawerethat the participants must have worked in the hospital for at least one full year in the case of government hospitals and 6 full months in the case of private hospitals and may be working in any of the following areas of the hospital: the medical, surgical, surgery/gynecology, neonatology/pediatrics, wards, the theater, intensive care unit, blood bank/hematology, chemical pathology, bacteriology/parasitology,histopathologylaboratories,the HIVcareunit, wastehandlingunitandthecompoundingordispensingpharmacy units. The study participants (n = 660) were administered personally to healthcare workers consisting of 101 doctors, 159 nurses, 30 pharmacists, 20 waste handlers and 40 medical laboratory scientists from selected government hospitals and 86 doctors,158nurses,14pharmacists,15wastehandlersand37medical laboratory scientists from selected private hospitals.

2.2. Ethical consideration

Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital, Nnewi and Anambra State University Teaching Hospital Amaku, Awka Ethics Committees approved the study protocols (approval numbers: NAUTH/CS/66/Vol.4/53 and ANSUTH/AA/ECC/29 respectively) and permission to carry out the study was obtained.

2.3. Method of data analysis

Data was analyzed using SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, United States of America). Comparative statistics was used for quantitative data. Frequency distribution of variables was calculated. Chi-square was used to test association between the independent variables and their outcomes. The cut-off point for statistical significance was set at 5% (P<0.05).

3. Results

Among the healthcare workers that participated in the study, 187 (28.33%) were medical doctors, 44 (6.67%) were pharmacists, 77 (11.67%) were medical laboratory scientist, 35 (5.30%) were waste handlers and 317 (48.03%) were nurses.

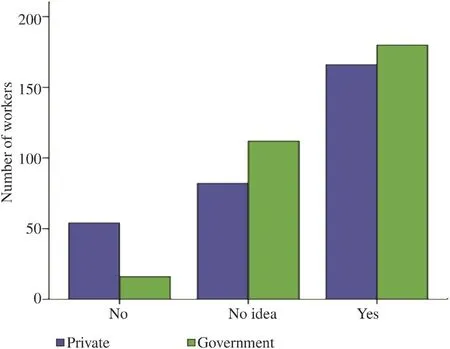

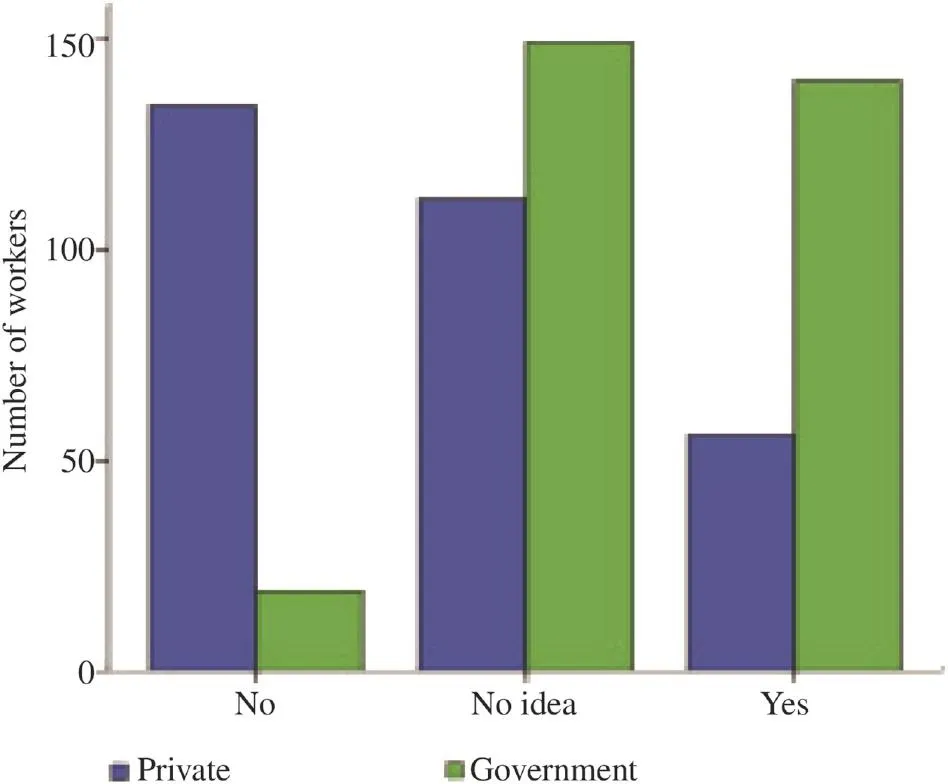

Figure 1 shows the number of healthcare workers that have heard of healthcare waste disposal system (HCWDS). From the study, the awareness of HCWDS was greater in government hospitals 251 (81.5%) when compared with that of private hospitals at 173 (57.3%). Generally, the number of workers that have heard about it was above average 424 (69.5%). There was significant difference (P = 0.001) in the level of knowledge of workers between the institutions being compared.

Figure 2 shows the analysis of healthcare workers that have attended training on HCWDS. The study showed that only 71 (11.6%) participants in the study had attended training on HCWDS. The number that have attended training on HCWDS in private and government hospitals were 21 (7.0%) and 50 (16.2%) respectively showing that significant difference (P = 0.001) existed between them.

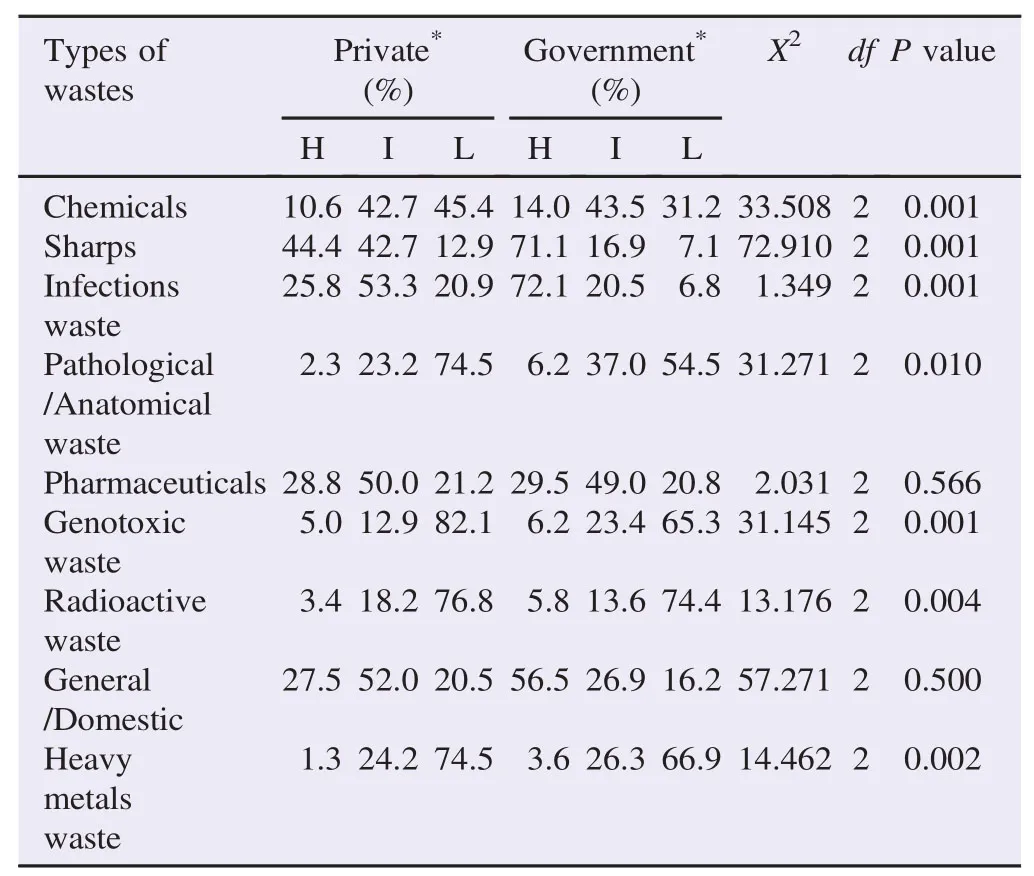

The study showed (Table 1) that the level of waste generated by the two hospitals differed significantly (P = 0.0086) with the generation level in government hospitals higher than that in private hospitals. In public hospitals, the wastes generation level in descending order was as follows: infectious waste (72.1%), sharps (71.1%), general/domestic (56.5%), pharmaceutical (29.5%), chemicals (14.0%), pathological (6.2%), genotoxic (6.2%), radioactive (5.8%), heavy metal waste (3.6%). For private hospitals, the wastes generation level was in the following order: sharps (44.4%), pharmaceutical (28.8%), general (27.5%), infectious (25.8%), chemicals (10.6%), genotoxic (5.0%), radioactive (3.4%), pathological (2.3%), heavy metals (1.3%).

Figure 1. Analysis of the knowledge of healthcare workers on HCWDS.

Table 2 assesses the risks associated with the healthcare waste in the hospitals. Our findings showed that both hospitalswere exposed to equal risks (P = 0.8510). The risks associated with the healthcare wastes were categorized as high risks, intermediate risks and low risks for the study. Similarly, pharmaceuticals were chosen to pose intermediate risk with a percentage of 35.6% and general or domestic waste possessing the least level of risk with an average percentage of 91.6%. There was no significant difference (all P values>0.05) in the participants' knowledge (private vs. government hospitals) about the risks posed by healthcare waste.

Figure 2. Analysis on number of healthcare workers that have attended training on HCWDS.

Table 1Analysis of waste generation level in the institutions.

Table 2Analysis on level of risks associated with different wastes.

Figure 3. Analysis on existence of HCWDS in the hospitals.

Figure 3 shows the participants' knowledge of the existence of HCWDS in their hospitals. The study showed that 166 (55.0%) and 180 (55.4%) of workers in private and public hospitals respectively confirmed the existence of HCWDS in their hospitals with 54 (17.9%) and 16 (5.2%) of the study participants saying that HCWDS did not exist. Generally, the percentage that answered yes was 56.7% which was above average, indicating the existence of HCWDS in the hospitals. There was significant difference (P = 0.001) in the existence of HCWDS in the two hospitals with the existence more in government hospitals.

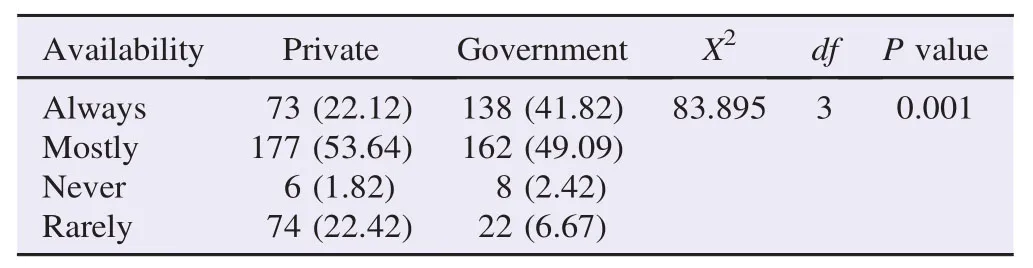

Table 3 shows the analysis of the availability of materials for healthcare waste disposal in institutions visited. The study showed that 73 (22.12%) and 138 (41.82%) of the workers answered‘always’, 177 (53.64%) and 162 (49.09%) workers answered‘mostly’, 6 (1.82%) and 8 (2.42%) workers answered ‘never’, while 74 (22.42%) and 22 (6.67%) workers answered ‘rarely’in private and government hospitals respectively. This result showed it was more available in government hospitals than private hospitals and significant difference (P = 0.001) existed in the institutions compared.

Table 3Analysis on availability of materials for healthcare waste disposal. n (%).

Generally, the availability for healthcare waste disposal in both government and private hospitals was poor. Materials for waste disposal should be always available. It was indispensable in hospitals for proper disposal and segregation of wasteso as to reduce the effect of nosocomial infections in the hospital [8].

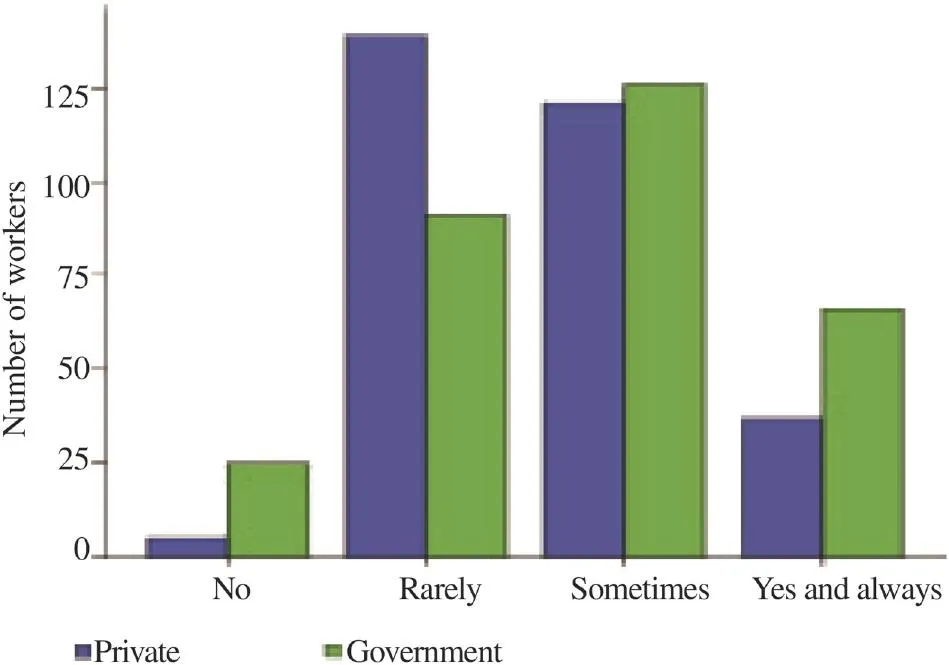

Figure 4 shows the rate and application of waste segregation at the point of generation in the hospital visited. The study showed that 37 (12.3%) and 66 (21.4%) of the study participants in private and government hospitals respectively practiced waste segregation always at point of generation in their day-to-day work.

Figure 4. The practice of waste segregation at the point of generation in hospitals visited.

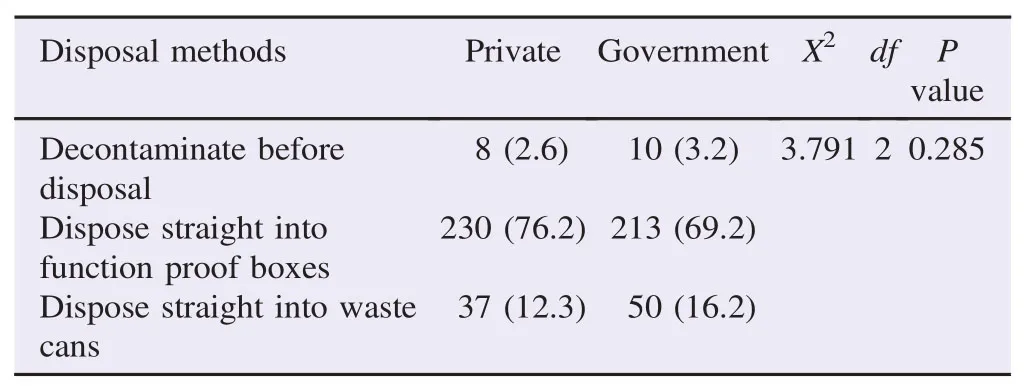

Table 4 shows the method used by the healthcare workers to dispose used needles and syringes. The result showed that 8 (2.6%) and 10 (3.2%) workers decontaminated before disposal, 230 (76.2%) and 213 (69.2%) workers disposed straight into puncture proof boxes while 37 (12.3%) and 50 (16.2%) workers disposed straight into waste cans in private and government hospitals respectively.

World Health Organization guideline for disposal of sharps said that it should be disposed in puncture proof containers with yellow color marked“sharps”[9]. The study showed that 72.6% of workers disposed straight into puncture proof boxes which complied with the rule. There was no significant difference (P = 0.285) in syringes and needles disposal practices in the two kinds of hospitals. However, highly infectious wastes should be sterilized and contaminated before use to reduce the spread of infection that come from that.

Figure 5 shows the knowledge of the study participants on the existence of healthcare waste management/infection control committee in their hospitals. Infection control was the series of activities or procedures put in place especially in hospitals, which discouraged or prevented the establishment of pathogenic organisms within the body to prevent them from gaining access into the host [10].

Table 4Ways adopted by healthcare workers in disposing used syringe and needles. n (%).

Figure 5. Existence of healthcare waste management committee and/or infection control committee.

The study showed that 56 (18.5%) and 140 (45.5%) of the study participants in private and government hospitals respectively were aware of the existence of healthcare waste management committee with 134 (44.4%) and 19 (6.2%) workers confirming that it did not exist in their institutions. The study showed that the existence of the committee was very low in the private hospitals. There was significant difference (P = 0.001) in the existence of the committee in the two institutions with the infection committee being higher in government hospitals.

4. Discussion

There is limited knowledge of the healthcare workers on HCWDS (Figure 2) and reveals lack of waste segregation, improper handling and disposal of waste. Therefore, training and seminars should be organized so as to educate the healthcare workers on safe management of waste so as to reduce the incidence of nosocomial infections in the hospitals. Also, this reveals the quality of healthcare workers in the two hospitals and means that workers in government hospitals in Southeast Nigeria are better equipped than those in private hospitals. This may be due to some reasons ranging from enhanced income to greater quest for personal improvement.

World Health Organization guidelines predicted that hazardous waste should be between 10% and 25% generation levels [10]; this means that the level of waste generated (Table 1) is higher and above the specification. This can increase the risks and prevalence of nosocomial infection.

A work on improving the management of solid hospital waste in Nigeria tertiary hospital using questionnaire showed that 4.5% were pathological, 20% were infectious, 1.6% were sharps while 73.9% were non-infectious or general waste [11].

The high generation level witnessed in the hospitals visited means effort is needed to control the waste generation and proper training of healthcare workers and waste handlers are needed so as to prevent spread of infections emanating from this healthcare waste.

Our study (Table 2) agrees with previous publications showing that infectious wastes pose the highest risk (70.7%) of hazard both to the community and the environment [1,10,12,13].

Generally, the rate of segregation of waste always at the point of generation is poor or very low (Figure 4) in both thegovernment and private institutions (with 16.9% compliance). This is contrary with the finding of Shalini et al. in similar setting [14]. Wastes should be segregated at the point of generation before treatment and disposal to protect both humans and the environment. Segregation of waste would result in a clean solid waste stream which could be easily, safely and cost effectively managed through recycling, composting and landfilling[15].

A cross sectional study by Bassey et al. on 5 selected hospitals in Abuja found waste segregation to be zero [16]. Similar study also carried out by Longe and Williams in 4 selected hospitals in Lagos found 3 hospitals to practice waste segregation [17]. Also similar work on waste management in healthcare establishment within Jos metropolis in 6 major hospitals shows that none of the hospitals practice waste segregation [18].

Therefore, this shows that rules and regulations should be put in place and laws enacted so as to ensure proper waste segregation to prevent the rise in cases of nosocomial infection encountered in the hospitals. There is significant difference (P = 0.001) in the level of waste segregation in the hospitals with the government hospitals having higher waste generation as well as higher level of compliance to waste segregation.

Generally, the study (Figure 5) showed the existence of the infection control committee or person in both hospitals to be low (32.1%). Similar low level had been previously reported [19]. The infection control team or individual is responsible for the day-to-day functions of infection control, as well as preparing the yearly work plan for review by infection control committee and administration [20,21].

Therefore, effort to establish the committee in both private and government hospitals is needed so as to regulate the spread of infection within the hospital and also proper management of waste generated in the hospital.

The study revealed that healthcare workers in government hospitals have more knowledge on healthcare waste management system than those in private hospitals.

It also revealed that healthcare workers in government hospitals show more level of compliance to healthcare waste management guideline than those in private hospitals. Generally, the compliance level of the healthcare worker to the guidelines is poor as seen by the poor percentage of them that practice waste segregation. This is a major concern as poor compliance to the guidelines and other factors lead to the increase in nosocomial cases in the hospitals.

The study further showed that the existence of healthcare waste management/infection control committee is higher in government hospitals than private hospitals. However, the existence of committee in the two hospitals is generally low and unsatisfactory. This also contributes to the increase in cases of nosocomial infections, as the committee acts as surveillance to the activities in the hospitals to ensure that the healthcare waste management guideline is implemented.

The study also revealed that the existence of healthcare waste disposal in the two hospitals is above average but also showed that it is not always available in the units in the hospital. Adequate provision of materials for waste disposal ensures proper isolation, segregation and disposal of waste which helps to reduce the incidence of nosocomial infections in the hospitals. Poor availability of the materials for the disposal contributes to the cases of nosocomial infection in the hospital.

From the study, it was revealed that the availability of material for waste segregation at point of generation, the compliance of healthcare workers to healthcare guidelines and the existence of infection control committee is generally low and unsatisfactory. It is therefore recommended that: government should support hospitals with modern waste disposal systems and equipment and engage more persons for the day-to-day cleaning of the hospitals; government should enforce the preparation and implementation of institutional waste management plan in the hospitals; training of more hospital heath workers through attending conferences, seminars and workshops in order to increase their knowledge about hospital waste, its risks and sanitation; development of standards on healthcare waste management for hospitals, disseminate such standards to various hospitals and encourage various hospitals to conduct a critical self-appraisal on their healthcare in accordance with set standards.

Conflict of interest statement

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the financial support of Mr. and Mrs. Ekejindu in carrying out the study. The authors also wish to appreciate the co-operations of all the participants in the study as well as the management of the hospitals used in the study for allowing the study to be done.

References

[1] Manyele SV, Mujuni CM. Current status of sharps waste management in the lower-level health facilities in Tanzania. Tanzan J Health Res 2010; 12(4): 266-73.

[2] Rodriguez-Morales AJ. Current topics in public health. Rijeka: InTech; 2013.

[3] World Health Organization. Media centre. Waste from health-care activities. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Online] Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs253/ en/ [Accessed on 20th May, 2015]

[4] Adedigba MA, Nwhator SO, Afon A, Abegunde AA, Bamise CT. Assessment of dental waste management in a Nigerian tertiary hospital. Waste Manag Res 2010; 28: 769-77.

[5] Department of Health. Environment and sustainability Health Technical Memorandum 07-01: safe management of healthcare waste. United Kingdom: Department of Health; 2013. [Online] Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/ uploads/attachment_data/file/167976/HTM_07-01_Final.pdf [Accessed on 20th May, 2015]

[6] Ogbonna DN. Characteristics and waste management practices of medical wastes in healthcare institutions in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. J Soil Sci Environ Manag 2011; 2(5): 132-41.

[7] Bagheri Nejad S, Allegranzi B, Syed SB, Ellisc B, Pittet D. Healthcare-associated infection in Africa: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ 2011; 89: 757-65.

[8] Rasslan O, Seliem ZS, Ghazi IA, El Sabour MA, El Kholy AA, Sadeq FM, et al. Device-associated infection rates in adult and pediatric intensive care units of hospitals in Egypt. International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium (INICC)findings. J Infect Public Health 2012; 5: 394-402.

[9] World Health Organization. Management of solid healthcare waste at primary healthcare centres: a decision making guide. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. [Online] Available from: http:// www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/publications/manhcwm.pdf [Accessed on 20th May, 2015]

[10] Higgins A, Hannan MM. Improved hand hygiene technique and compliance in healthcare workers using gaming technology. J Hosp Infect 2013; 84: 32-7.

[11] Abah SO, Ohimain EI. Healthcare waste management in Nigeria: a case study. J Public Health Epidemiol 2011; 3(3): 99-110.

[12] World Health Organization. Management of waste from injection activities at district level. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Online] Available from: http://www.who.int/water_ sanitation_health/medicalwaste/mwinjections/en/ [Accessed on 20th May, 2015]

[13] Stanley HO, Okpara KE, Chukwujekwu DC, Agbozu IE, Nyenke CU. Health care waste management in Port Harcourt Metropolis. Am J Sci Ind Res 2011; 2(5): 769-73.

[14] Shalini S, Harsh M, Mathur BP. Evaluation of bio-medical waste management practices in a government medical college and hospital. Natl J Community Med 2012; 3(1): 80-4.

[15] Health Care without Harm. Eleven recommendations for improving medical waste management. Buenos Aires: Health Care Without Harm; 2002.

[16] Bassey BE, Benka-Coker MO, Aluyi HS. Characterization and management of solid medical wastes in the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja Nigeria. Afr Health Sci 2006; 6(1): 58-63.

[17] Longe EO, Williams A. A preliminary study on medical waste management in Lagos Metropolis, Nigeria. Iran J Environ Health Sci Eng 2006; 3: 133-9.

[18] Ngwuluka N, Ochekpe N, Odumosu P, John SA. Waste management in healthcare establishments within Jos Metropolis Nigeria. Afr J Environ Sci Technol 2009; 3(12): 459-65.

[19] Oli AN, Nweke JN, Ugwu MC, Anagu LO, Oli AH, Esimone CO. Knowledge and use of disinfection policy in some government hospitals in South-East, Nigeria. Br J Med Med Res 2013; 3(4): 1097-108.

[20] David OM, Famurenwa O. Toward effective management of nosocomial infections in Nigerian hospitals-a review. Academic Arena 2010; 2(5): 1-7.

[21] Sydnor ER, Perl TM. Hospital epidemiology and infection control in acute-care settings. Clin Microbiol Rev 2011; 24(1): 141-73.

Epidemiological investigation http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apjtb.2015.09.018

*Corresponding author:Angus Nnamdi Oli, Department of Pharmaceutical Microbiology and Biotechnology, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Agulu Campus, Anambra State, Nigeria.

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine2016年1期

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine2016年1期

- Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine的其它文章

- The antibacterial activity of selected plants towards resistant bacteria isolated from clinical specimens

- Isolation of aerobic bacteria from ticks infested sheep in Iraq

- Rhinacanthus nasutus leaf improves metabolic abnormalities in high-fat diet-induced obese mice

- Influence of extraction solvents on antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of the pulp and seed of Anisophyllea laurina R. Br. ex Sabine fruits

- Antifungal activity of plant extracts with potential to control plant pathogens in pineapple

- Potent water extracts of Indonesian medicinal plants against PTP1B