视觉单通道还是视听双通道?

——通道效应的元分析*

王福兴 谢和平 李 卉

(1青少年网络心理与行为教育部重点实验室; 华中师范大学心理学院, 武汉 430079)

(2天津师范大学心理与行为研究院, 天津 300074)

1 引言

多媒体技术的发展与应用在向学习者提供前所未有的契机与便利之时, 也为实现高效学习提出了一定的挑战。相比传统的学习方式, 尽管多媒体教学能够有效地利用视觉或听觉材料传递更为生动逼真的信息, 帮助学习者建构概念性或过程性心理表征(Leopold & Mayer, 2015; Mayer,2009), 但往往也具有信息量大、元素的时空变化关系复杂等特点(Höffler & Leutner, 2007; Tversky,Morrison, & Betrancourt, 2002), 可能产生较高的认知负担。因此, 如何采用科学合理的指导性教学设计(instructional design)提高学习效果, 引起了多媒体学习研究者的关注(Clark & Mayer, 2011)。

1.1 通道效应与多媒体学习认知理论

信息呈现通道是在进行多媒体设计时需要考虑的一项重要因素。多媒体学习材料由画面和语词共同组成(Mayer, 2009)。其中, 画面主要通过视觉通道呈现, 如:图片、视频、动画等; 而语词既可通过视觉通道呈现, 如:屏幕文本、打印文本等, 也可采用听觉通道呈现, 如:声音解说。“画面+视觉文本”形成视觉单通道材料, 而“画面+声音解说”组成视听双通道材料。因此, 从这个意义上讲, 多媒体学习是对来自视觉单通道或视听双通道图文信息的选择、组织与整合的高级加工过程。那么, 不同通道对多媒体学习效果的影响是否存在差异?围绕该问题, 许多研究者进行了大量实证探索(Moreno & Mayer, 1999; Mousavi, Low,& Sweller, 1995; Schüler, Scheiter, Rummer, &Gerjets, 2012; Schmidt-Weigand, Kohnert, &Glowalla, 2010a; Tabbers & van der Spoel, 2011)。

多媒体学习领域的研究发现, 学习者学习由“画面+声音解说”组成的视听双通道材料的效果要好于学习由“画面+视觉文本”组成的视觉单通道材料, 表现为相对更高的保持测验或迁移测验成绩, 该现象即被称为通道效应(modality effect)(Mayer, 2009)。目前, 视听双通道相对视觉单通道的优势已经得到来自生理学(Brünken & Leutner,2001; Park, Moreno, Seufert, & Brünken, 2011)、气象学(Craig, Gholson, & Driscoll, 2002; Mayer &Moreno, 1998)、生物学(Moreno & Mayer, 2002)、数学(Kalyuga, Chandler, & Sweller, 2000)、统计学(Tindall-Ford & Sweller, 2006)、机械工程学(Kalyuga, Chandler, & Sweller, 1999; Mayer, Dow,& Mayer, 2003)等众多学科材料的实证支持。

关于通道效应产生的原因, 研究者多从多媒体学习认知理论(Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning, CTML)的视角进行解释(Mayer, 2009)。该理论提出了双通道假设(dual-channel assumption)和容量有限假设(limited-capacity assumption)等基本观点。双通道假设认为, 个体对视觉和听觉表征的学习材料分别拥有单独的信息加工通道; 容量有限假设进一步认为, 个体在每个通道中单位时间内加工的信息是有限的。综合以上观点, 当学习材料为“画面+声音解说”时, 加工画面信息更多消耗视觉通道中的工作记忆资源, 加工声音解说信息更多消耗听觉通道中的工作记忆资源(Leahy, Chandler, & Sweller, 2003), 各通道容量超载的可能性均相对较小, 外在认知负荷相对较低;反之, 当学习材料为“画面+视觉文本”时, 加工视觉文本同加工画面一样会更多消耗视觉通道中的资源, 此时学习者需要同时在视觉通道中加工画面和语词信息, 容易在图文之间分离注意, 所以与“画面+声音解说”相比, 工作记忆资源有限的视觉通道此时更容易超出认知负荷(Park et al.,2011; Sweller, van Merriënboer, & Paas, 1998)。由此, 在多媒体学习的图文整合过程中, 声音解说相比视觉文本更具优势。

1.2 逆转通道效应与文本加工策略

尽管大量研究结果支持了通道效应, 但近年来仍有不少研究者发现了相反的结果, 出现了所谓的逆转通道效应(reverse modality effect) (Cheon,Crooks, Inan, Flores, & Ari, 2011; Sanchez & Garcia-Rodicio, 2008; Sullins, Craig, & Graesser, 2010;Tabbers, Martens, & van Merriënboer, 2004)。例如:Leahy和 Sweller (2011)研究发现, 视觉单通道条件下的学习效果比视听双通道更好。随后, Crooks,Cheon, Inan, Ari和Flores (2012)以及Inan等(2015)均发现视觉文本相比声音解说更能促进学习者对语词和画面的识记与理解等。

而关于逆转通道效应产生的原因, 可从文本加工策略(text processing strategies)角度加以解释(Crooks, Inan, Cheon, Ari, & Flores, 2009; Inan et al., 2015)。文本加工策略包括主动控制阅读速度、返回阅读、重读关键文本、略读非关键文本或在文本间来回跳读等策略(Furnham, de Siena, &Gunter, 2002)。在视觉文本条件下, 即使不能控制学习进程, 学习者也拥有相对较多的时间运用文本加工策略(Kühl, Eitel, Damnik, & Körndle, 2014),而这些策略的灵活使用有助于学习者积极建构语词和画面信息之间的丰富联结, 优化学习效果(Cheon et al., 2011); 相对而言, 声音解说则具有天然的线性特征, 不易灵活采用上述文本加工策略以深入理解学习材料(Crooks et al., 2012)。从这一角度看, 视觉文本在多媒体环境中可能存在潜在的优越性。

针对通道效应和逆转通道效应的不一致结果,Ginns (2005)早在十年前就对其进行了元分析, 并发现了通道效应的稳健性(d综合=0.72)。但该元分析在单个实验的结果变量选取上是唯一的, 且存在以下优先选择标准:(1)按照迁移测验、保持测验、问题解决时间以及主观认知负荷等指标的先后顺序优先选取; (2)结果显著的指标优先选取。例如:若某项实验中的因变量为保持测验和主观认知负荷, 但前者不显著, 后者显著, 则只将后者纳入元分析。显然, 这种选取方法可能导致对效应量的高估, 且丢失了许多有价值的数据。此外, 保持测验或迁移测验普遍被研究者分别用来考察学习者的浅层识记或深层理解效果(Mayer,2009), 但 Ginns (2005)仅在迁移测验上发现了较强的通道效应(d迁移=0.76), 而非保持测验(d保持=0.01)。这可能是由于上述优先选取标准导致该研究在保持测验上生成的独立效应量较少(n保持=6,n迁移=25), 从而影响了结果的精确性(Borenstein,Hedges, Higgins, & Rothstein, 2009)。再者, Ginns(2005)并未进行发表偏差检验, 结果可靠性有待商榷。近十年来, 国内外研究者继续就多媒体学习中的通道效应进行了大量深入研究, 因此有必要针对以上缺陷重新对其进行元分析。根据CTML, 本研究预期:在保持测验上, 视听双通道(画面+声音解说)比视觉单通道(画面+视觉文本)更能提高学习成绩(假设 1); 在迁移测验上, 同样存在稳定的通道效应, 但其效应量比Ginns (2005)的研究结果低(假设2)。

1.3 通道效应的重要边界条件

Mayer (2010)认为, 多媒体学习中的原则或效应可能受其他因素的调节, 这些调节因素即为该效应的边界条件(boundary condition)。综述先前研究发现, 呈现步调、画面动态性以及材料时长可能是通道效应的重要潜在边界条件。

1.3.1 呈现步调

呈现步调可分为学习者步调(learner-paced)和系统步调(system-paced) (Tabbers & De Koeijer,2010)。前者指学习进程可由学习者自行控制(如:播放、暂停、回放、终止等), 具有一定的交互性;后者指学习进程由多媒体系统控制, 交互性较低。因此, 对呈现步调的操纵主要涉及学习者与多媒体平台的交互性或学习者对学习进程的控制能力, 而这种交互性或控制能力可能影响通道效应的强弱。以往许多研究发现, 系统步调条件下的通道效应较强(Kalyuga et al., 1999; Moreno &Mayer, 2002); 而学习者步调条件下, 该效应则会减小或消失(Harskamp, Mayer, & Suhre, 2007;Wouters, Paas, & van Merriënboer, 2008), 甚至出现逆转(Crooks et al., 2012; Tabbers et al., 2004)。Ginns (2005)也发现系统步调下的通道效应高于学习者步调(d系统=0.93,d学习者=−0.14)。可能的原因是:材料为系统步调时, 视觉单通道比视听双通道需要更多的认知资源以在图文元素间进行转换加工, 易产生注意分离和更高的外在认知负荷(Ginns, 2005), 因此声音解说在认知负荷及学习成绩上相对视觉文本更具优势; 若材料为学习者步调, 则无论是视觉单通道还是视听双通道,学习者均有足够的时间和资源整合图文信息, 认知负荷均较低, 甚至前者更有利于文本加工策略的充分发挥(Inan et al., 2015), 故二者差距减小,甚至反转。由此, 本研究预期:系统步调条件下通道效应的效应量显著高于学习者步调(假设3)。

1.3.2 画面动态性

根据画面材料的动态性, 可分静态和动态两类(Tversky et al., 2002)。静态画面中材料的元素以相对静止的形式呈现给学习者, 而动态画面中的材料元素在空间位置上具有运动性。因此, 画面动态性主要与画面中元素的运动属性有关。有研究者认为, 通道效应的产生并不能仅仅归于声音解说相对于视觉文本的通道优势(Kühl, Scheiter,Gerjets, & Edelmann, 2011), 画面动态性可能也起到了重要的调节作用。而这一点并没有受到应有的重视(Ginns, 2005)。动态画面往往转瞬即逝, 相对更为复杂(Höffler & Leutner, 2007), 学习者对视觉通道资源的依赖性较强, 若动态画面与视觉文本相结合, 则在视觉通道中的资源竞争相比声音解说更高, 产生更强的分离注意效应(splitattention effect) (Sweller et al., 1998)和更高的认知负荷, 不利于学习; 相反, 若材料画面为静态, 画面的视觉复杂性降低, 即使语词也以视觉形式呈现, 学习者对视觉通道资源的依赖性并不会像动态画面那样强烈, 因此, 声音解说和视觉文本条件下的认知负荷均可能较低, 学习效果均较好。综合而言, 当画面材料为动态时, 声音解说与视觉文本之间的效果差异相比静态画面更大, 通道效应更强。因此, 本研究预期:动态画面条件下通道效应的效应量显著高于静态画面(假设4)。

1.3.3 材料时长

在众多有关通道效应的研究中, 多媒体学习材料的时间长度通常情况下即为学习者的学习时间, 但往往时长不等, 短则近百秒(Rummer,Schweppe, Fürstenberg, Seufert, & Brünken, 2008),长则数十分钟(Erlandson, Nelson, & Savenye,2010)。有研究者认为, 材料时长是通道效应另一重要的潜在边界条件(Kalyuga, 2012; Schweppe &Rummer, 2014), 但该因素同样未受到Ginns (2005)元分析的关注。Tabbers (2002)观察发现, 那些验证了通道效应的研究所采用的材料往往较短, 而未发现通道效应的研究中学习材料相对较长。这已得到Harskamp等人(2007)以及Leahy和Sweller(2011)的研究结果的支持。原因可能在于:当学习材料较长时, 为实现有效识记和理解, 学习者需在工作记忆中对先前呈现的知识进行较长时间的表征维持(representational holding) (Mayer &Moreno, 2003), 即使是声音解说, 也较难弥补长时间的表征维持所带来的高认知负荷, 因此不利于有效发挥声音解说相对于视觉文本的潜在优势;而材料时长较短时则相反。鉴于许多学习材料时长较短的研究通常低于10分钟(Moreno & Mayer,1999; Tindall-Ford & Sweller, 2006), 本研究尝试以10分钟为长短界限(10分钟以下为短, 10分钟及以上为长), 考察材料时长对通道效应的调节作用。研究推测:短时材料条件下通道效应的效应量显著高于长时材料(假设5)。

1.4 研究假设

综上, 根据 CTML, 呈现画面和声音解说不存在通道资源的竞争, 而呈现画面和视觉文本则可能存在视觉通道资源的竞争和超负荷, 因此本研究预期:在保持测验(假设 1)和迁移测验(假设2)上均会发现通道效应, 且与以往元分析结果存在一定差异; 此外, 由于通道效应可能在系统步调、动态画面、短时材料等条件下更强, 因此本研究还认为:系统步调条件下通道效应的效应量高于学习者步调(假设3), 动态画面条件下通道效应的效应量高于静态画面(假设4), 而短时材料条件下通道效应的效应量高于长时材料(假设5)。

2 方法

2.1 文献检索

采用英文和中文文献搜索方式获取通道效应的实证研究。对于英文文献, 主要将关键词“modality effect”、 “modality principle”、 “text modality”、“on-screen text and narration”、“written and spoken text”分别与“multimedia learning”、“animation”、“visualization”进行联合搜索, 搜索数据库包括 PsycINFO、Education Research Complete、Science Direct、PubMed、ERIC、ProQuest博硕士论文全文数据库等。对于中文文献, 主要将关键词“通道效应”、“通道原则”、“文本通道”、“屏幕文本和声音解说”、“书面文本和口语文本”分别与“多媒体学习”、“动画”、“可视化”进行联合搜索, 搜索数据库包括中国知网学术期刊网络出版总库、中国知网优秀博硕论文全文数据库、万方数据库、维普电子期刊等。同时通过文献回溯及Google scholar搜索方式进行补查。

2.2 文献纳入与排除

经文献检索后, 进一步按下列标准对其纳入与排除:(1)研究需为实证, 非实证研究予以排除;(2)根据多媒体学习定义(Mayer, 2009), 研究所用材料还需包含画面(如:图表、照片、视频、录像、动画), 纯文本(仅含语词)的阅读研究予以排除; (3)研究需为“画面+声音解说”与“画面+视觉文本”对比, 否则予以排除; (4)研究应报告可生成效应量的完整数据(如:平均数、样本量、标准差或t值、p值等), 否则予以排除; (5)研究中因变量应至少含保持测验、迁移测验中的一种, 否则予以排除;(6)研究数据不应重复, 重复研究予以排除。

经文献纳入后, 进一步按以下变量逐条进行编码:(1)基本信息(作者、时间、样本量); (2)呈现步调(学习者步调、系统步调); (3)画面动态性(静态、动态); (4)材料时长(长、短); (5)结果变量(保持测验、迁移测验); (6)效应量; (7) 95% CI。

选取保持测验和迁移测验作为结果变量的原因在于, 二者均为多媒体学习研究关注的与学习效果有关的重要后测指标(Mayer, 2009)。而对二者进行单独编码和分析的原因在于, 它们在测验方式和目的上均有所不同:保持测验通常要求学习者学习完材料之后对材料内容尽可能多的进行回忆,测验答案往往为学习材料本身, 由于该测验可能存在死记硬背的现象, 因此主要用以考察学习者的浅层识记效果; 而迁移测验通常是在学习者学习完材料之后要求其回答或解决与材料相关的另一些迁移性问题, 测验答案需要学习者主动从材料中加以推理, 该测验能较好地避免死记硬背的现象, 因此主要用来考察学习者的深层理解效果。

采用CMA 2.0 (Comprehensive Meta-Analysis 2.0)进行元分析。以“画面+声音解说”视听双通道为实验组, “画面+视觉文本”视觉单通道为控制组计算各研究效应量。由于所纳入文献的数据均为单位不统一的连续型数据, 且为了方便与以往研究(Ginns, 2005)进行对比, 本研究采用Cohen’sd作为效应量指标(Cohen, 1988)。为避免单篇文献因含多个实验或多个条件而生成过多效应量, 占用过多权重, 从而导致一定的结果偏差(Borenstein et al.,2009), 研究采用CMA 2.0对可事先进行数据合并的文献经过合并处理后, 再将该合并效应量(pooled effect size)作为该文献的最终样本。

2.4 模型选定

元分析结果的计算可采用固定效应模型(fixed-effects model)或随机效应模型(random-effects model)。不同的模型由于存在权重分配的差异, 最后得到的效应量结果也可能有所不同(Borenstein et al., 2009)。固定效应模型假定所有纳入元分析的研究都拥有同一真实效应量, 其研究对象、研究方法等均相同, 仅基于研究内变异计算权重,倾向于赋予小样本研究较小权重, 赋予大样本研究较大权重; 随机效应模型则允许研究间真实效应量的不同, 其研究对象、研究方法等也均各异,基于研究内和研究间变异计算权重, 权重分配较固定效应模型更为平衡。对于模型的选择, 可采用异质性检验(heterogeneity test)判定。若效应量异质, 适合采用随机效应模型。

2.5 发表偏差

从文章发表来看, 有统计学意义的研究往往更容易发表, 而发表后的研究更容易被纳入元分析。这可能导致实际纳入的研究与理应被纳入的研究之间存在系统性误差, 从而出现发表偏差,影响元分析结果(Borenstein et al., 2009)。本研究采用失安全系数(Rosenthal’s fail-safe number,Nfs)、Egger线性回归检验(Egger linear regression test)以及剪补法(trim and fill method)评价发表偏差。

3 结果

3.1 文献纳入及编码

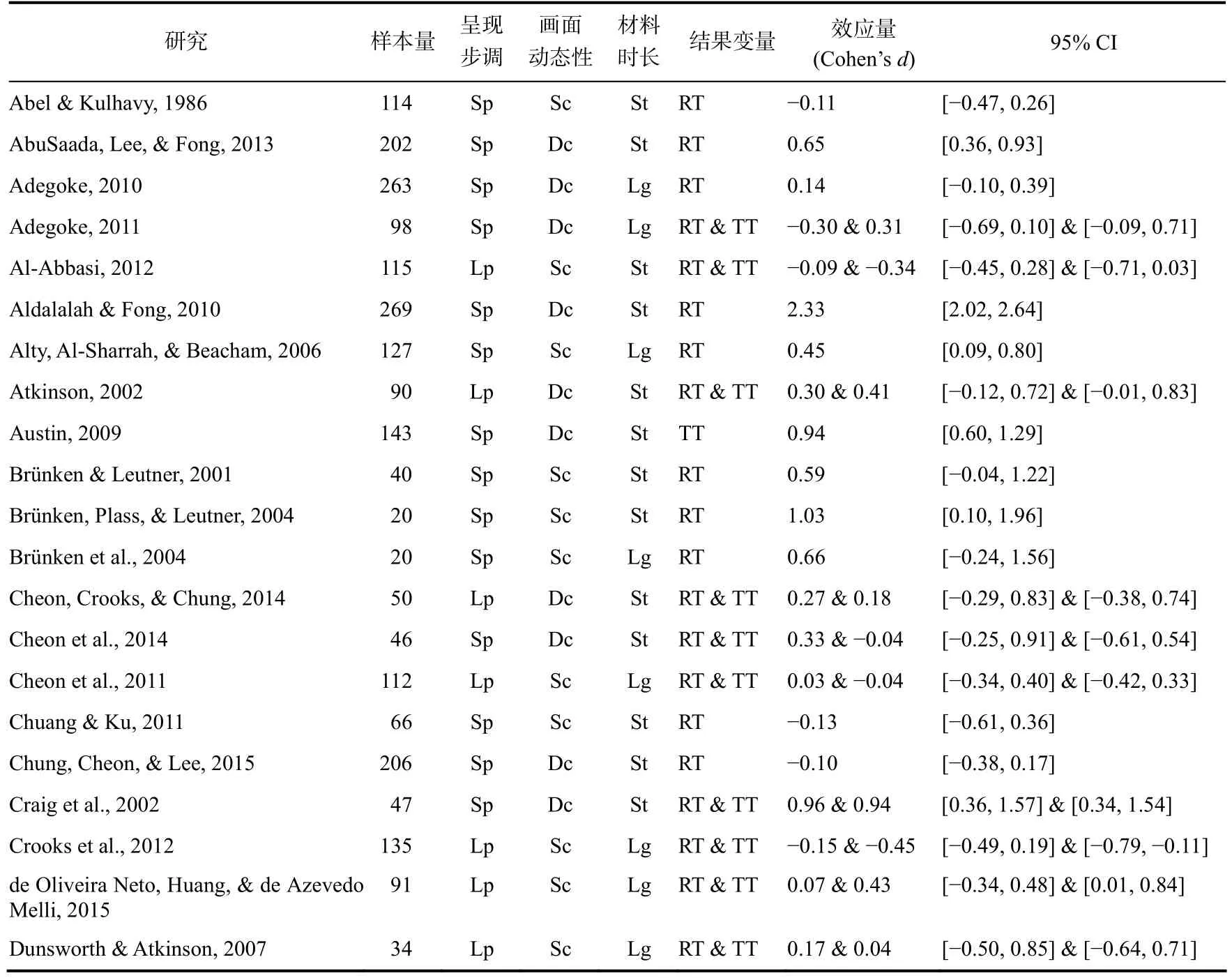

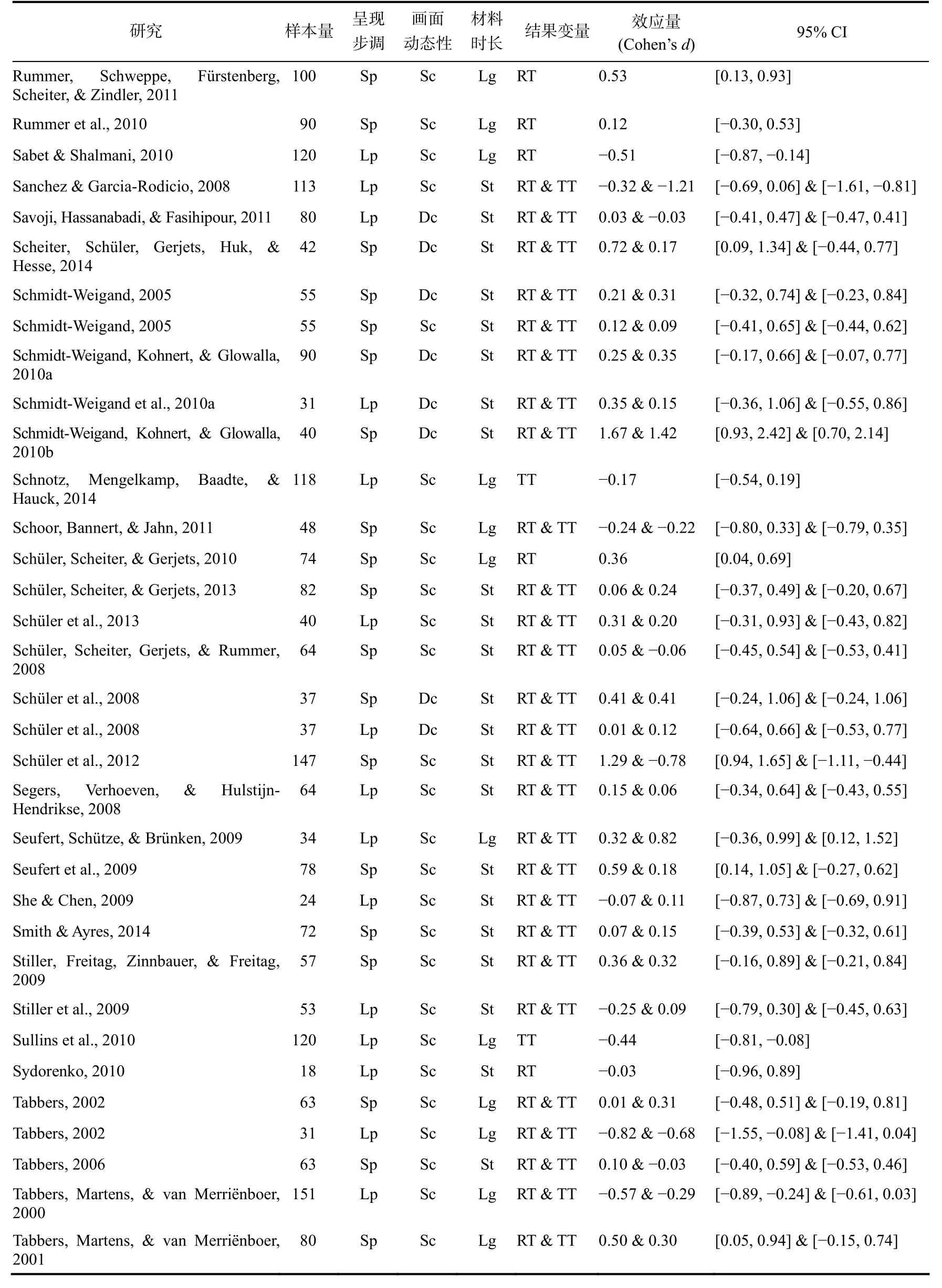

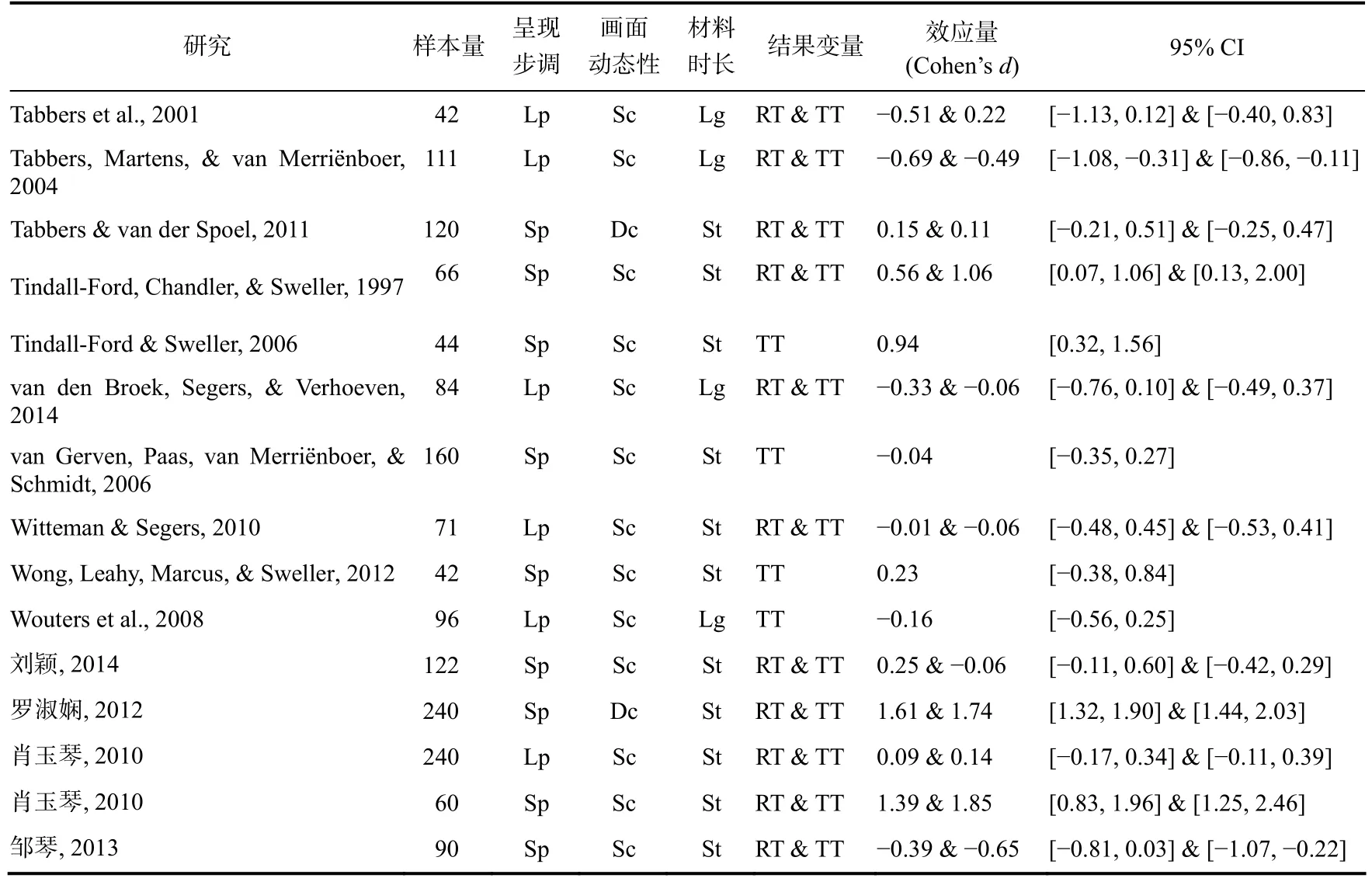

为尽量避免不必要的数据丢失并保证结果的精确性, 本研究在结果变量的选取上并未像Ginns (2005)那样设置优先选择标准, 而是将保持测验和迁移测验分别进行单独编码和分析, 故单篇文献的效应量可能并不唯一。经文献检索和排除后, 共有91篇符合标准的文献纳入元分析, 其中77篇含保持测验(被试8088人), 68篇含迁移测验(被试 6664人)。经效应量合并等处理后, 最终保持测验共生成94个独立效应量, 迁移测验共生成83个独立效应量。文献编码结果见表1。

表1 多媒体学习中通道效应的元分析

续表1

续表1

续表1

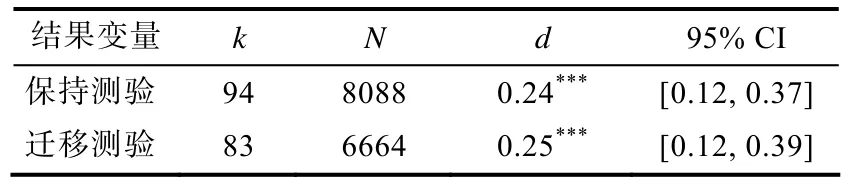

3.2 主效应检验

选择随机效应模型(下同)分别对保持测验和迁移测验下的通道效应进行主效应检验(见表2)。结果发现, 二者的平均效应量d分别为 0.24和0.25。若将0.2、0.5、0.8分别看作效应量小、中、大的界限(Cohen, 1992), 那么通道效应在两个结果变量上的效应量均较小。但双尾检验发现p值都小于0.001, 表明视听双通道比视觉单通道更能提高保持和迁移成绩, 促进学习者的识记和理解效果。95%置信区间的下限均大于0, 说明该效应量由偶然因素引起的可能性非常小。

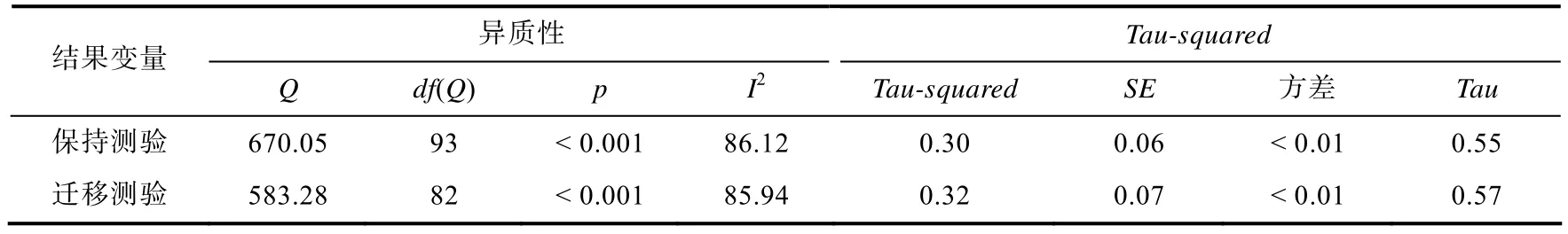

3.3 异质性检验

分别对保持测验和迁移测验进行异质性检验(见表3)。结果发现, 二者Q检验均显著(p< 0.001),这表明效应量是异质的, 因此选择随机效应模型比较合理。从二者的I2值来看, 保持测验为86.12%,迁移测验为85.94%, 表明两个结果变量中由效应量的真实差异造成的变异分别占总变异的86.12%和85.94%。元分析时, 25%、50%、75%大致可看作异质性低、中、高的界限(Higgins,Thompson, Deeks, & Altman, 2003), 且根据Cochrane系统评价, 只要I2不大于 50%, 其异质性便可以接受(Higgins & Green, 2011)。由此, 本研究中效应量的异质性均较高, 且都不可忽视。此外, 效应量的高异质性还意味着通道效应可能存在重要的潜在调节变量(Cooper, 1989), 需进一步进行调节效应检验。

表2 通道的主效应检验(随机效应模型)

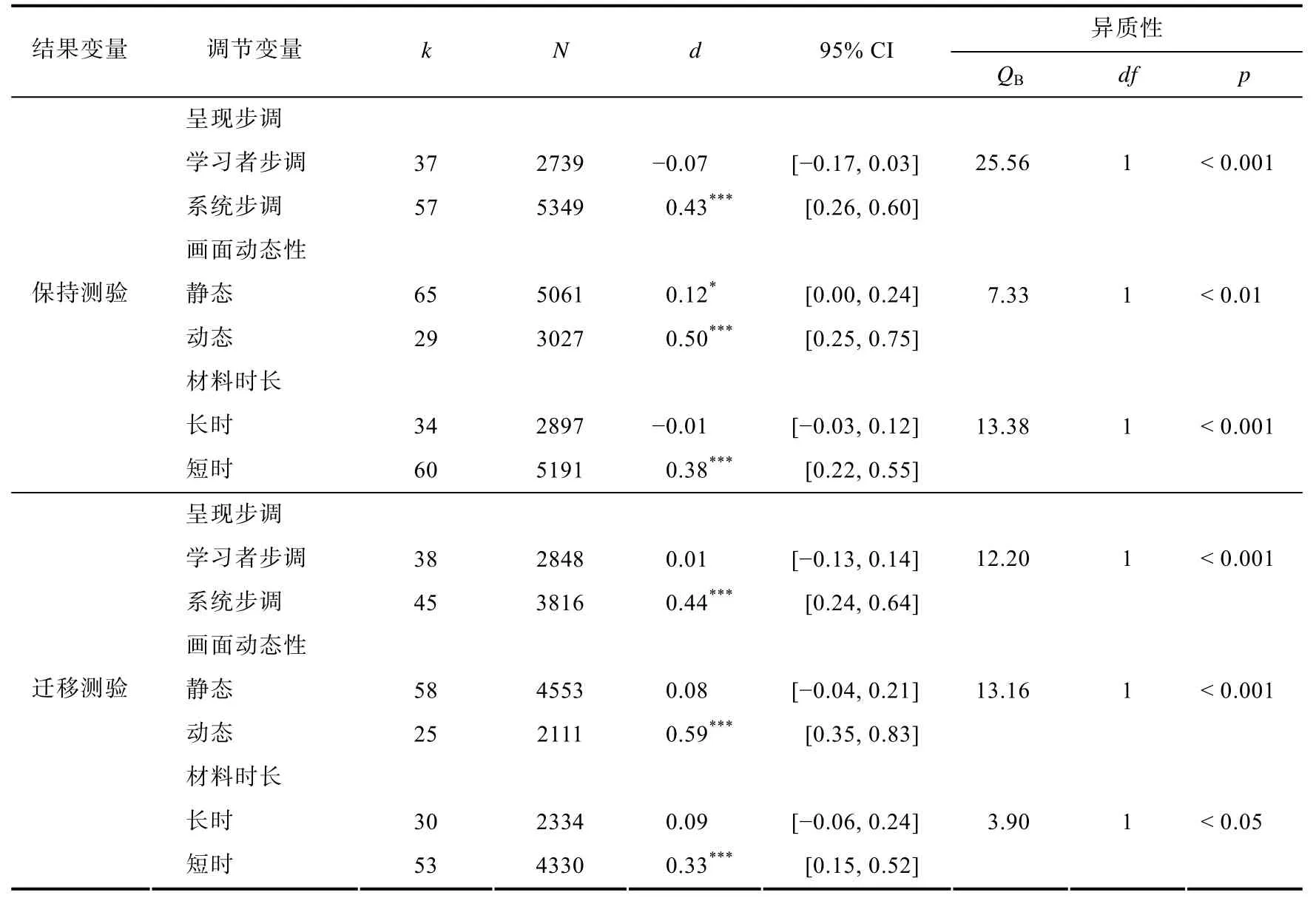

3.4 调节效应检验

分别对呈现步调、画面动态性和材料时长是否调节通道效应进行检验(见表4)。

从保持测验上看:呈现步调对通道效应起显著调节作用, 系统步调(d系统=0.43)高于学习者步调(d学习者=−0.07),QB(1)=25.56,p< 0.001; 画面动态性对通道效应起显著调节作用, 动态画面(d动态=0.50)高于静态画面(d静态=0.12),QB(1)=7.33,p< 0.01; 材料时长对通道效应也起到显著调节作用, 短时材料(d短时=0.38)高于长时材料(d长时=−0.01),QB(1)=13.38,p< 0.001。

表3 效应量异质性检验

表4 多媒体学习中通道效应的调节效应检验(随机效应模型)

从迁移测验上看:呈现步调对通道效应起显著调节作用, 系统步调(d系统=0.44)高于学习者步调(d学习者=0.01),QB(1)=12.20,p< 0.001; 画面动态性对通道效应起显著调节作用, 动态画面(d动态=0.59)高于静态画面(d静态=0.08),QB(1)=13.16,p< 0.01; 材料时长对通道效应也起到显著调节作用, 短时材料(d短时=0.33)高于长时材料(d长时=0.09),QB(1)=3.90,p< 0.05。

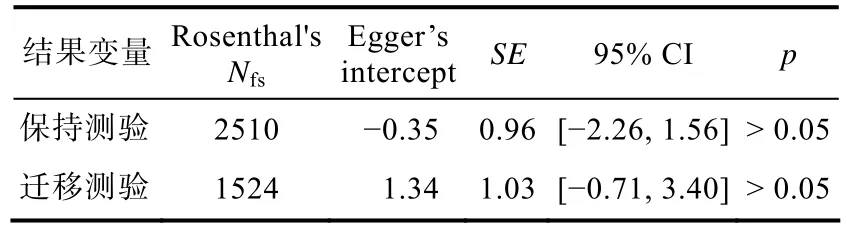

3.5 发表偏差检验

研究采用以下方法检验发表偏差(见表5)。首先, 如果失安全系数(Rosenthal'sNfs)小于临界值5k+ 10 (k指纳入元分析的独立效应量个数), 则表明可能存在发表偏差(Rothstein, Sutton, &Borenstein, 2005)。本研究中在保持测验和迁移测验上该系数均超过 1500, 远远大于临界值, 因此该指标表明本研究存在发表偏差的可能性较小。其次, 如果 Egger线性回归检验的回归方程截距(Egger’s intercept)越接近0, 则存在发表偏差的可能性越小(Egger, Smith, Schneider, & Minder,1997)。本研究中在两结果变量上该值分别为−0.35、1.34, 接近0, 且95% CI均包含0,p值不显著, 因此该指标也表明本研究存在发表偏差的可能性较小。最后, 采用剪补法对效应量左右两边文献进行剪补后, 发现效应量仍显著。综上所述, 本研究并不存在不可忽视的发表偏差。

表5 发表偏差检验

4 讨论

针对以往研究(Ginns, 2005)可能存在的缺陷,本研究重新对多媒体学习中的通道效应进行了元分析。结果证实, 视听双通道比视觉单通道更能促进保持测验和迁移测验成绩, 但通道效应主要在系统步调、动态画面及短时材料条件下出现。因此, 通道效应稳定存在, 支持了多媒体学习认知理论, 且呈现步调、画面动态性和材料时长是通道效应的重要边界条件。

4.1 视觉单通道还是视听双通道?

主效应检验结果显示, “画面+声音解说”比“画面+视觉文本”更能提高保持测验和迁移测验成绩, 验证了假设1和假设2中预期的通道效应。因此, 在多媒体学习的图文整合过程中, 视听双通道比视觉单通道更具优势, 这与多媒体学习认知理论的观点一致(Mayer, 2009)。

画面和语词是多媒体学习的基本元素, 画面仅以视觉表征形式呈现, 而语词不仅能以视觉形式呈现(视觉文本), 也能以听觉形式呈现(声音解说)。根据CTML, 个体拥有单独的视觉信息加工通道和听觉信息加工通道, 不同表征形式的信息主要在各自对应的通道中得以加工(Mayer, 2009)。所以当画面和视觉文本相结合时, 学习者仅在视觉单通道中选择、组织和整合图文信息; 而当同时呈现画面和声音解说时, 学习者可分别在视觉和听觉双通道中理解材料。然而, 每个通道中资源容量的有限性导致视觉单通道和视听双通道两种情况下的信息加工效率产生差异(She & Chen,2009)。当呈现画面和视觉文本时, 二者在早期的信息选择阶段共同竞争有限的注意资源, 可能产生分离注意效应, 而在后期的信息组织和整合阶段则易导致视觉通道中工作记忆的超负荷(Rummer et al., 2011; Rummer et al., 2010); 反之,画面和声音解说在早期注意阶段并不存在资源竞争, 二者互不干扰, 后期各通道超载的几率也相对较小。

需要指出的是, 本研究结果与 Ginns (2005)的元分析在效应量上存在差异。首先, 在保持测验上, 本研究得出的效应量为 0.24 (p< 0.001),而Ginns (2005)的结果仅为0.01 (p> 0.05)。其次,在迁移测验上, 本研究的效应量为 0.25, 远低于Ginns (2005)得到的值 0.76。因此证实了研究预期。我们认为, 这些效应量上的差异可能是因为Ginns (2005)研究中结果变量的选取缺陷导致的,即 Ginns的刻意选择其实夸大了迁移测验上通道效应的效力并影响了保持测验的结果。

4.2 通道效应的边界条件

调节效应检验结果证实, 呈现步调、画面动态性、材料时长是通道效应的重要边界条件。

首先, 系统步调在保持测验和迁移测验上的通道效应的效应量分别为0.43和0.44, 均显著高于学习者步调, 验证了假设3。由于学习者步调条件下的效应量均不显著, 因此通道效应主要在系统步调条件下出现。在多媒体学习中, 当学习进程由系统控制时, 学习者的可学习时间往往固定,人机交互性较低, 注意资源的竞争及视觉通道容量的有限性使得学习者在加工“画面+视觉文本”时相对更容易分离注意, 并产生较高的认知负荷(Rummer et al., 2011), 因此不如“画面+声音解说”的效果好; 而如果在有限的时间内给予学习者对学习进程的主动控制权, 那么无论语词以何种通道呈现, 学习者均可以根据当前学习状况调整学习策略, 例如:略过已掌握的知识、重播难点知识等, 而这些对信息的组织和整合具有重要的意义(Kalyuga, 2012; Tabbers et al., 2004)。不过, 需要说明, 虽然本研究系统步调在通道效应上的优势与 Ginns (2005)的研究结果存在一致性, 但在效应量上较其研究(d=0.93)仍然要低, 因此本研究结果可能相对更为谨慎和严格。这也体现了重新纳入最近 10年新的研究并重新进行通道效应元分析的价值。

其次, 动态画面在保持测验和迁移测验上的通道效应的效应量达到中等偏大水平, 分别为0.50和 0.59, 显著高于静态画面, 故当画面为动态时, 视听双通道更有利于促进对材料的识记和理解, 与假设 4一致。尽管动态可视化材料能够更好地模拟或真实再现物体的运动特征(如:速度、移动方向等) (Mayer & Moreno, 2002), 但其转瞬即逝以及高元素交互性的特点使得它对视觉通道资源的依赖性也更强(Kühl et al., 2011), 因此相比声音解说而言, 当语词以视觉文本信息呈现时,图文信息的注意资源竞争性增强(Sweller et al.,1998), 视觉通道易超载; 而静态画面对视觉通道资源的依赖并没有动态画面高, 因此可留出更多的资源加工语词信息, 即使是与静态画面竞争注意资源的视觉文本。故视听双通道与视觉单通道在静态画面条件下的差距比动态画面更小。然而意外的是, 当画面为静态时, 在保持测验而非迁移测验上发现了显著的通道效应, 这可能与保持测验和迁移测验的差别有关。保持测验仅涉及对材料的浅层识记、回忆或再认, 测验答案通常为材料内容本身; 而迁移测验需要在识记材料的基础上进行深层理解, 并运用到其他类似的问题解决过程中去(Mayer, 2009)。能够识记或回忆学习内容, 并不代表已经理解透彻并触类旁通; 但深入理解了材料之后, 往往会更容易再认和回忆。换言之, 保持比迁移可能相对容易。因此, 静态材料中, 视听双通道比视觉单通道的浅层识记效果更好, 保持测验比迁移测验更易发现通道效应。这得到了Dunsworth和Atkinson (2007)研究结果的支持。

最后, 短时材料在两个结果变量上的通道效应的效应量分别达0.38和0.33, 也都显著高于长时材料, 验证了假设5。由于长时材料条件下的效应量均不显著, 因此通道效应主要在短时材料条件下出现。这与先前研究者的观点或结果具有一致性(Harskamp et al., 2007; Kalyuga, 2012; Tabbers,2002)。例如:Leahy和Sweller (2011)发现, 在学习较短的材料时, 视听双通道条件下的理解效果比视觉单通道更好; 但将同样的材料延长时间后,通道效应消失。一般认为, 在多媒体学习中, 原本有限的认知资源除了需要用于对材料的选择、组织和整合等基本加工(essential processing)外, 还要用于表征维持。所谓表征维持, 是指在一段时间段内将多媒体材料的心理表征维持于工作记忆中以保证高效学习的认知过程(Mayer & Moreno,2003)。当材料稍短时, 表征维持难度较低, 无需消耗过多资源, 基本加工过程的资源相对充足,因此易于发挥声音解说相对于视觉文本的潜力;若持续学习时间过长, 表征维持难度增大, 该过程的工作记忆负荷相应增加(Kalyuga, 2012), 从而占用基本加工过程中的认知资源, 即使语词以听觉形式呈现, 也可能因资源不足而降低加工效率, 因而抑制了通道效应的产生。

需要注意的是, 一方面, 无论是主效应检验,还是调节效应检验, 本研究均没有发现逆转通道效应, 并未支持文本加工策略在视觉文本中的加工优势的观点。因此, 关于文本加工策略在多媒体学习中的适用范围和适应力, 还有待深入研究。另一方面, 尽管本研究结果支持了多媒体学习认知理论, 但通道效应产生的具体原因仍不明确。Rummer等人(2010)为更好地理解通道效应,总结了两种假说:分离注意假说(split attention assumption)认为, 早期感觉记忆阶段的注意资源竞争导致通道效应; 而视觉空间负荷假说(visuospatial load hypothesis)认为, 后期工作记忆阶段的通道资源超载是通道效应产生的原因。那么,到底是分离注意, 还是视觉空间负荷, 抑或二者的共同作用?后续研究需要借助更为合适的方法和技术(如:眼动)深入探讨。

另外, 结合以往的理论观点来看, 多媒体学习中通道效应的理论解释本身至少存在以下两方面值得思考的问题:第一, 视、听通道的交互作用对各通道本身资源消耗的影响没有引起多媒体学习研究者的足够重视。个体对视、听通道的信息加工并不是绝对相互独立、互不干扰的(Driver& Spence, 2000), 而这种视听交互到底是促进认知还是干扰认知也未成定论(Stein, London, Wilkinson,& Price, 1996; Tata, Prime, McDonald, & Ward,2001)。从这一角度讲, 视、听通道中所消耗的资源量在特定条件(如:“画面+视觉文本”或“画面+声音解说”)下是否一定会超过(或不超过)通道资源总量仍待商榷和深入考证。第二, 多媒体学习认知理论认为, 视觉文本易引起视觉通道超载,而这一观点与Baddeley的工作记忆模型并不一致(Crooks et al., 2012; Rummer et al., 2011), 因为最初的工作记忆模型(Baddeley & Hitch, 1974)认为所有的语词(视觉文本和声音解说)都是在语音环路(phonological loop) (即听觉通道)中得到加工的,而非视觉空间模板(visuo-spatial sketchpad) (即视觉通道)。总之, 多媒体学习的通道效应还需要在理论上进一步强化研究。

5 结论

研究结论如下:(1)相比视觉单通道, 当图文信息以视听双通道呈现时更有利于促进对多媒体学习材料的识记和理解, 保持测验和迁移测验成绩更高, 支持了多媒体学习认知理论; (2)呈现步调、画面动态性以及材料时长是通道效应的重要边界条件, 系统步调、动态画面以及短时材料条件下的通道效应更强。

*为纳入元分析文献

*刘颖.(2014).感知学习风格对通道效应的影响研究(硕士学位论文).河北大学, 保定.

*罗淑娴.(2012).通道效应在老年人多媒体学习中的有效性研究(硕士学位论文).湖南师范大学, 长沙.

*肖玉琴.(2010).通道效应在交互性多媒体学习环境中的有效性研究(硕士学位论文).湖南师范大学, 长沙.

*邹琴.(2013).内外部线索对多媒体学习效果的影响: 来自眼动的证据(硕士学位论文).华中师范大学, 武汉.

*Abel, R.R., & Kulhavy, R.W.(1986).Maps, mode of text presentation, and children’s prose learning.American Educational Research Journal, 23(2), 263–274.

*AbuSaada, A.H., Lee, L.P.L., & Fong, S.F.(2013).Effects of modality principle in tutorial video streaming.International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 3(5), 456–466.

*Adegoke, B.A.(2010).Integrating animations, narratives and textual information for improving physics learning.Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology,8(2), 725–748.

*Adegoke, B.A.(2011).Effect of multimedia instruction on senior secondary school students’ achievement in Physics.European Journal of Educational Studies, 3(3), 537–550.

*Al-Abbasi, D.(2012).The effects of modality and multimedia comprehension on the performance of students with varied multimedia comprehension abilities when exposed to high complexity, self-paced multimedia instructional materials.Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia, 21(3), 215–239.

*Aldalalah, O.M., & Fong, S.F.(2010).Effects of modality and redundancy principles on the learning and attitude of a computer-based music theory lesson among Jordanian primary pupils.International Education Studies, 3(3),52–64.

*Alty, J.L., Al-Sharrah, A., & Beacham, N.(2006).When humans form media and media form humans: An experimental study examining the effects different digital media have on the learning outcomes of students who have different learning styles.Interacting with Computers,18(5), 891–909.

*Atkinson, R.K.(2002).Optimizing learning from examples using animated pedagogical agents.Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(2), 416–427.

*Austin, K.A.(2009).Multimedia learning: Cognitive individual differences and display design techniques predict transfer learning with multimedia learning modules.Computers & Education, 53(4), 1339–1354.

Baddeley, A.D., & Hitch, G.J.(1974).Working memory.In G.H.Bower (Ed.),The psychology of learning and motivation: Advances in research and theory(pp.47–89).New York: Academic Press.

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L.V., Higgins, J.P.T., & Rothstein,H.R.(2009).Introduction to meta-analysis.Chichester,UK: Wiley.

*Brünken, R., & Leutner, D.(2001).Aufmerksamkeitsverteilung oder Aufmerksamkeitsfokussierung? Empirische Ergebnisse zur "Split-Attention-Hypothese" beim Lernen mit Multimedia.(Attention Splitting or Attention Focussing? Empirical Results Concerning the "Split-Attention Hypothesis" in Learning with Multimedia).Unterrichtswissenschaft, 29(4),357–366.

*Brünken, R., Plass, J.L., & Leutner, D.(2004).Assessment of cognitive load in multimedia learning with dual-task methodology: Auditory load and modality effects.Instructional Science, 32(1–2), 115–132.

*Cheon, J., Crooks, S.M., & Chung, S.(2014).Does segmenting principle counteract modality principle in instructional animation?British Journal of Educational Technology, 45(1), 56–64.

*Cheon, J., Crooks, S.M., Inan, F.A., Flores, R., & Ari, F.(2011).Exploring the instructional conditions for a reverse modality effect in multimedia instruction.Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia, 20(2), 117–133.

*Chuang, H.-Y., & Ku, H.-Y.(2011).The effect of computerbased multimedia instruction with Chinese character recognition.Educational Media International, 48(1), 27–41.

*Chung, S., Cheon, J., & Lee, K.-W.(2015).Emotion and multimedia learning: An investigation of the effects of valence and arousal on different modalities in an instructional animation.Instructional Science, 43(5), 545–559.

Clark, R.C., & Mayer, R.E.(2011).E-learning and the science of instruction: Proven guidelines for consumers and designers of multimedia learning(3rd ed.).Hoboken,NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Cohen, J.(1988).Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences(2nd ed.).New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cohen, J.(1992).A power primer.Psychological Bulletin,112(1), 155–159.

Cooper, H.M.(1989).Integrating research: A guide forliterature reviews(2nd ed.).Newbury Park, CA: SAGE.

*Craig, S.D., Gholson, B., & Driscoll, D.M.(2002).Animated pedagogical agents in multimedia educational environments: Effects of agent properties, picture features and redundancy.Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(2),428–434.

*Crooks, S.M., Cheon, J., Inan, F., Ari, F., & Flores, R.(2012).Modality and cueing in multimedia learning:Examining cognitive and perceptual explanations for the modality effect.Computers in Human Behavior, 28(3),1063–1071.

Crooks, S.M., Inan, F., Cheon, J., Ari, F., & Flores, R.(2009).When text should be seen and not heard: An instance of the reverse modality effect in multimedia learning.InProceeding of the annual convention of the association for educational communications and technology(Vol.1, pp.91–93).Louisville, KY.

*de Oliveira Neto, J.D., Huang, W.D., & de Azevedo Melli,N.C.(2015).Online learning: Audio or text?Educational Technology Research and Development, 63(4), 555–573.

Driver, J., & Spence, C.(2000).Multisensory perception:Beyond modularity and convergence.Current Biology,10(20), R731–R735.

*Dunsworth, Q., & Atkinson, R.K.(2007).Fostering multimedia learning of science: Exploring the role of an animated agent’s image.Computers & Education, 49(3),677–690.

Egger, M., Smith, G.D., Schneider, M., & Minder, C.(1997).Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test.British Medical Journal, 315(7109), 629–634.

*Erlandson, B.E., Nelson, B.C., & Savenye, W.C.(2010).Collaboration modality, cognitive load, and science inquiry learning in virtual inquiry environments.Educational Technology Research and Development, 58(6), 693–710.

*Fiorella, L., Vogel-Walcutt, J.J., & Schatz, S.(2012).Applying the modality principle to real-time feedback and the acquisition of higher-order cognitive skills.Educational Technology Research and Development, 60(2), 223–238.

*Flores, R., Coward, F., & Crooks, S.M.(2010).Examining the influence of gender on the modality effect.Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 39(1), 87–103.

Furnham, A., de Siena, S., & Gunter, B.(2002).Children's and adults’ recall of children's news stories in both print and audio-visual presentation modalities.Applied Cognitive Psychology, 16(2), 191–210.

*Gerjets, P., Scheiter, K., Opfermann, M., Hesse, F.W., &Eysink, T.H.S.(2009).Learning with hypermedia: The influence of representational formats and different levels of learner control on performance and learning behavior.Computers in Human Behavior, 25(2), 360–370.

Ginns, P.(2005).Meta-analysis of the modality effect.Learning and Instruction, 15(4), 313–331.

*Grimley, M.(2007).Learning from multimedia materials:The relative impact of individual differences.Educational Psychology, 27(4), 465–485.

*Gyselinck, V., Jamet, E., & Dubois, V.(2008).The role of working memory components in multimedia comprehension.Applied Cognitive Psychology, 22(3), 353–374.

*Harskamp, E.G., Mayer, R.E., & Suhre, C.(2007).Does the modality principle for multimedia learning apply to science classrooms?Learning and Instruction, 17(5),465–477.

*Hassanabadi, H., Robatjazi, E.S., & Savoji, A.P.(2011).Cognitive consequences of segmentation and modality methods in learning from instructional animations.Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 30, 1481–1487.

Higgins, J.P.T., & Green, S.(2011).Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0[updated March 2011]: The Cochrane Collaboration.Retrieved August 22, 2015, from www.cochrane-handbook.org.

Higgins, J.P.T., Thompson, S.G., Deeks, J.J., & Altman, D.G.(2003).Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses.British Medical Journal, 327(7414), 557–560.

Höffler, T.N., & Leutner, D.(2007).Instructional animation versus static pictures: A meta-analysis.Learning and Instruction, 17(6), 722–738.

*Hoogerheide, V., Loyens, S.M.M., & van Gog, T.(2014).Comparing the effects of worked examples and modeling examples on learning.Computers in Human Behavior, 41,80–91.

*Inan, F.A., Crooks, S.M., Cheon, J., Ari, F., Flores, R.,Kurucay, M., & Paniukov, D.(2015).The reverse modality effect: Examining student learning from interactive computerbased instruction.British Journal of Educational Technology,46(1), 123–130.

*Jeung, H.J., Chandler, P., & Sweller, J.(1997).The role of visual indicators in dual sensory mode instruction.Educational Psychology, 17(3), 329–345.

Kalyuga, S.(2012).Instructional benefits of spoken words:A review of cognitive load factors.Educational Research Review, 7(2), 145–159.

*Kalyuga, S., Chandler, P., & Sweller, J.(1999).Managing split-attention and redundancy in multimedia instruction.Applied Cognitive Psychology, 13(4), 351–371.

*Kalyuga, S., Chandler, P., & Sweller, J.(2000).Incorporating learner experience into the design of multimedia instruction.Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(1), 126–136.

*Koroghlanian, C., & Klein, J.D.(2004).The effect of audio and animation in multimedia instruction.Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia, 13(1), 23–46.

Kühl, T., Eitel, A., Damnik, G., & Körndle, H.(2014).The impact of disfluency, pacing, and students’ need for cognition on learning with multimedia.Computers in Human Behavior, 35, 189–198.

*Kühl, T., Scheiter, K., Gerjets, P., & Edelmann, J.(2011).The influence of text modality on learning with static and dynamic visualizations.Computers in Human Behavior,27(1), 29–35.

*Leahy, W., Chandler, P., & Sweller, J.(2003).When auditory presentations should and should not be a component of multimedia instruction.Applied Cognitive Psychology, 17(4), 401–418.

*Leahy, W., & Sweller, J.(2011).Cognitive load theory,modality of presentation and the transient information effect.Applied Cognitive Psychology, 25(6), 943–951.

Leopold, C., & Mayer, R.E.(2015).An imagination effect in learning from scientific text.Journal of Educational Psychology, 107(1), 47–63.

*Levin, J.R., & Divine-Hawkins, P.(1974).Visual imagery as a prose-learning process.Journal of Literacy Research,6(1), 23–30.

*Lindow, S., Fuchs, H.M., Fürstenberg, A., Kleber, J.,Schweppe, J., & Rummer, R.(2011).On the robustness of the modality effect: Attempting to replicate a basic finding.Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psychologie, 25(4), 231–243.

*Main, R.E., & Griffiths, B.(1977).Evaluation of audio and pictorial instructional supplements.AV Communication Review, 25(2), 167–179.

*Mann, B.L.(1997).Evaluation of presentation modalities in a hypermedia system.Computers & Education, 28(2),133–143.

*Mann, B.L., Newhouse, P., Pagram, J., Campbell, A., &Schulz, H.(2002).A comparison of temporal speech and text cueing in educational multimedia.Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 18(3), 296–308.

Mayer, R.E.(2009).Multimedia learning(2nd ed.).New York: Cambridge University Press.

Mayer, R.E.(2010).Unique contributions of eye-tracking research to the study of learning with graphics.Learning and Instruction, 20(2), 167–171.

*Mayer, R.E., Dow, G.T., & Mayer, S.(2003).Multimedia learning in an interactive self-explaining environment:What works in the design of agent-based microworlds?Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(4), 806–813.

*Mayer, R.E., & Moreno, R.(1998).A split-attention effect in multimedia learning: Evidence for dual processing systems in working memory.Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(2), 312–320.

Mayer, R.E., & Moreno, R.(2002).Animation as an aid to multimedia learning.Educational Psychology Review,14(1), 87–99.

Mayer, R.E., & Moreno, R.(2003).Nine ways to reduce cognitive load in multimedia learning.Educational Psychologist, 38(1), 43–52.

*Mayrath, M.C., Nihalani, P.K., & Robinson, D.H.(2011).Varying tutorial modality and interface restriction to maximize transfer in a complex simulation environment.Journal of Educational Psychology, 103(2), 257–268.

*McNeill, A.L.(2004).The effects of training, modality, and redundancy on the development of a historical inquiry strategy in a multimedia learning environment(Unpublished master’s thesis).Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

*Moreno, R., & Mayer, R.E.(1999).Cognitive principles of multimedia learning: The role of modality and contiguity.Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(2), 358–368.

*Moreno, R., & Mayer, R.E.(2002).Learning science in virtual reality multimedia environments: Role of methods and media.Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(3),598–610.

*Moreno, R., Mayer, R.E., Spires, H.A., & Lester, J.C.(2001).The case for social agency in computer-based teaching: Do students learn more deeply when they interact with animated pedagogical agents?Cognition and Instruction, 19(2), 177–213.

Mousavi, S.Y., Low, R., & Sweller, J.(1995).Reducing cognitive load by mixing auditory and visual presentation modes.Journal of Educational Psychology, 87(2), 319–334.

*Nugent, G.C.(1982).Pictures, audio, and print: Symbolic representation and effect on learning.Educational Communication and Technology Journal, 30(3), 163–174.

*Park, B., Flowerday, T., & Brünken, R.(2015).Cognitive and affective effects of seductive details in multimedia learning.Computers in Human Behavior, 44, 267–278.

*Park, B., Moreno, R., Seufert, T., & Brünken, R.(2011).Does cognitive load moderate the seductive details effect?A multimedia study.Computers in Human Behavior, 27(1),5–10.

*Rias, R.M., Zaman, H.B., & Norhana.(2011).Modality effects in multimedia learning: A case study.Paper presented at the 2011 3rd International Congress on Engineering Education (ICEED).Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Rothstein, H.R., Sutton, A.J., & Borenstein, M.(2005).Publication bias in meta-analysis: Prevention, assessment and adjustments.Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

*Rummer, R., Schweppe, J., Fürstenberg, A., Scheiter, K., &Zindler, A.(2011).The perceptual basis of the modality effect in multimedia learning.Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 17(2), 159–173.

*Rummer, R., Schweppe, J., Fürstenberg, A., Seufert, T., &Brünken, R.(2010).Working memory interference during processing texts and pictures: Implications for the explanation of the modality effect.Applied Cognitive Psychology, 24(2), 164–176.

*Sabet, M.K., & Shalmani, H.B.(2010).Visual and spoken texts in MCALL courseware: The effects of text modalities on the vocabulary retention of EFL learners.English Language Teaching, 3(2), 30–36.

*Sanchez, E., & Garcia-Rodicio, H.(2008).The use of modality in the design of verbal aids in computer-based learning environments.Interacting with Computers, 20(6),545–561.

*Savoji, A.P., Hassanabadi, H., & Fasihipour, Z.(2011).The modality effect in learner-paced multimedia learning.Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 30, 1488–1493.

*Schüler, A., Scheiter, K., & Gerjets, P.(2010).Does spatialverbal information interfere with picture processing in working memory? The role of the visuo-spatial sketchpad in multimedia learning.Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 32nd Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society.

*Schüler, A., Scheiter, K., & Gerjets, P.(2013).Is spoken text always better? Investigating the modality and redundancy effect with longer text presentation.Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1590–1601.

*Schüler, A., Scheiter, K., Gerjets, P., & Rummer, R.(2008).The modality effect in multimedia learning: Theoretical and empirical limitations.Paper presented at the Eighth International Conference for the Learning Sciences-ICLS 2008, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

*Schüler, A., Scheiter, K., Rummer, R., & Gerjets, P.(2012).Explaining the modality effect in multimedia learning: Is it due to a lack of temporal contiguity with written text and pictures?Learning and Instruction, 22(2), 92–102.

*Scheiter, K., Schüler, A., Gerjets, P., Huk, T., & Hesse, F.W.(2014).Extending multimedia research: How do prerequisite knowledge and reading comprehension affect learning from text and pictures.Computers in Human Behavior, 31,73–84.

*Schmidt-Weigand, F.(2005).Dynamic visualizations in multimedia learning: The influence of verbal explanations on visual attention, cognitive load and learning outcome(Unpublished doctorial dissertation).Universitätsbibliothek Gieβen.

*Schmidt-Weigand, F., Kohnert, A., & Glowalla, U.(2010a).A closer look at split visual attention in system- and self-paced instruction in multimedia learning.Learning and Instruction, 20(2), 100–110.

*Schmidt-Weigand, F., Kohnert, A., & Glowalla, U.(2010b).Explaining the modality and contiguity effects: New insights from investigating students' viewing behaviour.Applied Cognitive Psychology, 24(2), 226–237.

*Schnotz, W., Mengelkamp, C., Baadte, C., & Hauck, G.(2014).Focus of attention and choice of text modality in multimedia learning.European Journal of Psychology of Education, 29(3), 483–501.

*Schoor, C., Bannert, M., & Jahn, V.(2011).Methodological constraints for detecting the modality effect.Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 9(3),1183–1196.

Schweppe, J., & Rummer, R.(2014).Attention, working memory, and long-term memory in multimedia learning:An integrated perspective based on process models of working memory.Educational Psychology Review, 26(2),285–306.

*Segers, E., Verhoeven, L., & Hulstijn-Hendrikse, N.(2008).Cognitive processes in children's multimedia text learning.Applied Cognitive Psychology, 22(3), 375–387.

*Seufert, T., Schütze, M., & Brünken, R.(2009).Memory characteristics and modality in multimedia learning: An aptitude–treatment–interaction study.Learning and Instruction, 19(1), 28–42.

*She, H.-C., & Chen, Y.-Z.(2009).The impact of multimedia effect on science learning: Evidence from eye movements.Computers & Education, 53(4), 1297–1307.

*Smith, A., & Ayres, P.(2014).Investigating the modality and redundancy effects for learners with persistent pain.Educational Psychology Review, 1–24.

Stein, B.E., London, N., Wilkinson, L.K., & Price, D.D.(1996).Enhancement of perceived visual intensity by auditory stimuli: A psychophysical analysis.Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 8(6), 497–506.

*Stiller, K.D., Freitag, A., Zinnbauer, P., & Freitag, C.(2009).How pacing of multimedia instructions can influence modality effects: A case of superiority of visual texts.Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 25(2),184–203.

*Sullins, J., Craig, S.D., & Graesser, A.C.(2010).The influence of modality on deep-reasoning questions.International Journal of Learning Technology, 5(4), 378–387.

Sweller, J., van Merriënboer, J.J.G., & Paas, F.G.W.C.(1998).Cognitive architecture and instructional design.Educational Psychology Review, 10(3), 251–296.

*Sydorenko, T.(2010).Modality of input and vocabulary acquisition.Language Learning & Technology, 14(2),50–73.

*Tabbers, H.K.(2002).The modality of text in multimedia instructions: Refining the design guidelines(Unpublished doctorial dissertation).Open University of the Netherlands,Heerlen, NL.

*Tabbers, H.K.(2006).Where did the modality effect go? A failure to replicate one of Mayer’s multimedia learning effects and why this still might make some sense.Paper presented at the Proceedings of the EARLI SIG 2 meeting“Learning by interpreting and constructing educational representations”, Nottingham, UK.

Tabbers, H.K., & De Koeijer, B.(2010).Learner control in animated multimedia instructions.Instructional Science,38(5), 441–453.

*Tabbers, H.K., Martens, R.L., & van Merriënboer, J.J.G.(2000).Multimedia instructions and cognitive load theory:Split-attention and modality effects.Paper presented at the National Convention of the Association for Educational Communications and Technology, Long Beach, CA.

*Tabbers, H.K., Martens, R.L., & van Merriënboer, J.J.G.(2001).The modality effect in multimedia instructions.Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 23rd annual conference of the Cognitive Science Society, Mahwah, NJ:Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

*Tabbers, H.K., Martens, R.L., & van Merriënboer, J.J.G.(2004).Multimedia instructions and cognitive load theory:Effects of modality and cueing.British Journal of Educational Psychology, 74(1), 71–81.

*Tabbers, H.K., & van der Spoel, W.(2011).Where did the modality principle in multimedia learning go? A double replication failure that questions both theory and practical use.Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psychologie, 25(4),221–230.

Tata, M.S., Prime, D.J., McDonald, J.J., & Ward, L.M.(2001).Transient spatial attention modulates distinct components of the auditory ERP.Neuroreport, 12(17),3679–3682.

*Tindall-Ford, S., Chandler, P., & Sweller, J.(1997).When two sensory modes are better than one.Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 3(4), 257–287.

*Tindall-Ford, S., & Sweller, J.(2006).Altering the modality of instructions to facilitate imagination: Interactions between the modality and imagination effects.Instructional Science, 34(4), 343–365.

Tversky, B., Morrison, J.B., & Betrancourt, M.(2002).Animation: Can it facilitate?International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 57(4), 247–262.

*van den Broek, G., Segers, E., & Verhoeven, L.(2014).Effects of text modality in multimedia presentations on written and oral performance.Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 30(5), 438–449.

*van Gerven, P.W.M., Paas, F., van Merriënboer, J.J.G., &Schmidt, H.G.(2006).Modality and variability as factors in training the elderly.Applied Cognitive Psychology,20(3), 311–320.

*Witteman, M.J., & Segers, E.(2010).The modality effect tested in children in a user-paced multimedia environment.Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 26(2), 132–142.

*Wong, A., Leahy, W., Marcus, N., & Sweller, J.(2012).Cognitive load theory, the transient information effect and e-learning.Learning and Instruction, 22(6), 449–457.

*Wouters, P., Paas, F., & van Merriënboer, J.J.G.(2009).Observational learning from animated models: Effects of modality and reflection on transfer.Contemporary Educational Psychology, 34(1), 1–8.