Impact and Friction Sensitivity of Energetic Materials:Methodical Evaluation of Technological Safety Features

Aleksandr Smirnov, Oleg Voronko, Boris Korsunsky, Tatyana Pivina

(1. Bakhirev State Scientific Research Institute of Mechanical Engineering, Dzerzhinsk, Nizhny Novgorod Region,

606002, Russia; 2. Institute of Problems of Chemical Physics, Russian Academy of Sciences, Chernogolovka, Moscow

Region, 142432, Russia; 3. Zelinsky Institute of Organic Chemistry, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, 119991, Russia)

Impact and Friction Sensitivity of Energetic Materials:Methodical Evaluation of Technological Safety Features

Aleksandr Smirnov1, Oleg Voronko1, Boris Korsunsky2, Tatyana Pivina3

(1. Bakhirev State Scientific Research Institute of Mechanical Engineering, Dzerzhinsk, Nizhny Novgorod Region,

606002, Russia; 2. Institute of Problems of Chemical Physics, Russian Academy of Sciences, Chernogolovka, Moscow

Region, 142432, Russia; 3. Zelinsky Institute of Organic Chemistry, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, 119991, Russia)

Abstract:Key methods developed and used in the USSR and in the Russian Federation to determine the impact and friction sensitivity of energetic materials and explosives have been discussed. Experimental methodologies and instruments that underlie the assessment of their production and handling safety have been described. Studies of a large number of compounds have revealed relationships between their sensitivity parameters and structure of individual compounds and compositions. The range of change of physical and chemical characteristics for the compounds we examined covers the entire region of their existence. Theoretical methodology and equations have been formulated to estimate the impact and friction sensitivity parameters of energetic materials and to evaluate the technological safety in use. The developed methodology is characterized by high-accuracy calculations and prediction of sensitivity parameters.

Keywords:energetic materials; experimental testing; friction sensitivity; impact sensitivity; regressive analysis; safety in use; methodical evaluation

Received date:2015-03-10;Revised date:2015-03-14

Biography:Aleksandr Smirnov, male, Ph.D, research field: experimental and theoretical investigations of energetic materials.

CLC number:TJ55;O645Document Code:AArticle ID:1007-7812(2015)03-0001-08

Introduction

Impact and friction sensitivity testing, along with the thermostability researches, sets the stage for all other performance and operability tests of energetic materials. A reason is that exactly these parameters underline safety rules of energetic materials handling both in the laboratory setting and in preparing their pilot and commercial batches, as well as munitions loading. The experimental measurement of sensitivity parameters and their computational evaluation options have been discussed in many papers internationally[1-13]. According to them, the sensitivity is primarily dependent on the oxidizer-propellant balance in an explosive. Also, in some of these papers, it is pointed out that a possible phase transfer of an explosive during impact sensitivity testing dramatically affects the resulting values.

Our paper review presents the Soviet and Russian researchers whose contribution to the understanding of these issues has been invaluable though actually unknown to the global professional community. Their findings supplemented and evolved by us served as a basis for our developments in this area.

Methods of sensitivity testing are numerous. They differ across instrumental designs, substance amounts needed for measurements as well as in the accuracy of theoretical evaluations. Furthermore, a rather correct risk-based categorization of substances is merely achievable through a comparison of generic characteristics in sequences of molecules with account of the existing diversity in instrumentation designs and computational methodologies. Therefore one of the key objectives of this research was to elaborate on specific methodological details of experimental methods for sensitivity assessment practiced in Russia and to develop a classification of substances by a degree of risk in their handling.

There are some by-country distinctions in the methodical approaches, however general impact sensitivity values for particular high energy materials obtained by different methods basically coincide with each other. The UN Recommendations on the Transport of Dangerous Goods[14]summarize globally recognized test methods for a relative impact sensitivity evaluation, some of which are similar to those set forth in Russian regulations.

In the USSR, N.A. Kholevo[15], Yu.B. Khariton[16], A.Ye. Pereverzev, K.K. Andreev[17]and many others created a foundation for various bench methods of the impact sensitivity measurement. In the 60-80s, a great contribution to the studies on the explosive sensitivity and improvement of the tests was made by V.S. Kozlov, S.M. Muratov, D.S. Avanesov, L.G. Bolkhovitinov[18], A.G. Merzhanov[19], G.T. Afanas′ev[20], A.V. Dubovik[21]and F.T. Khvorov. Although a scope of sensitivity parameters experimentally determined in Russia is rather wide, our paper focuses chiefly on the methodological specificity of drop weight tests and their results.

Impact and friction sensitivity parameters (impact sensitivity and friction sensitivity) were initially regarded as a basis of risk assessment for energetic materials, including as munition ingredients during the life cycle. It is known that drop weight tests simulate relatively slow impacts that are likely to occur in the technological processing and, due to the insufficient accuracy, are not used to predict the sensitivity of various energetic materials to shock waves and penetrative impacts, being the most hazardous in the munition transportation and in alert. That is why the impact sensitivity and friction sensitivity parameters, along with thermal stability data, are mainly utilized to determine acceptable process conditions and, in fact, should be attributed to industrial safety. Internal regulations in various explosives-producing countries commonly agree at the critical role of impact sensitivity parameters in risk assessment for the container transportation of powder explosives.

1Impact Sensitivity Tests

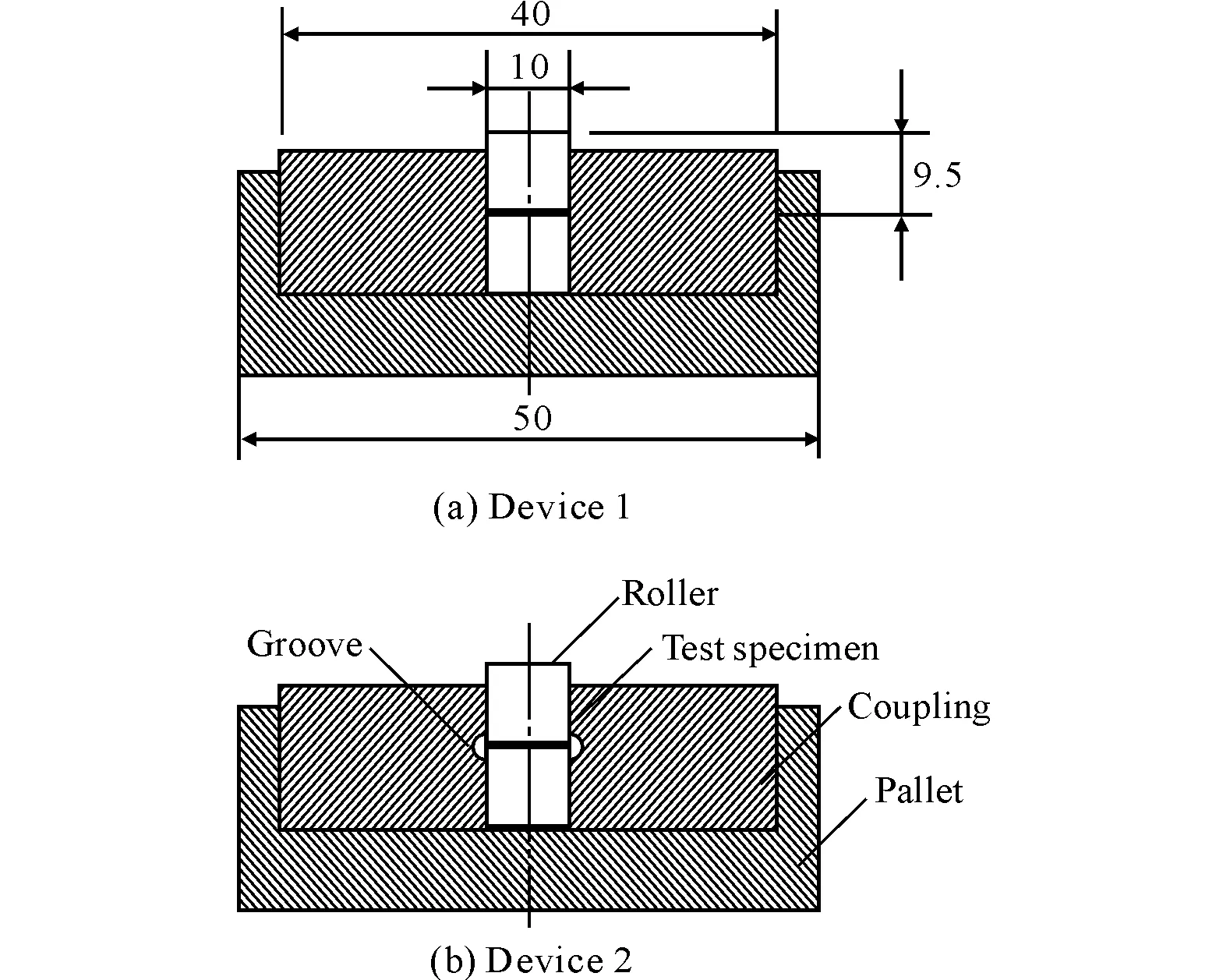

In Russia, the impact sensitivity of energetic materials and explosives is tested on drop weight machines designed at High Technical School in Kuibyshev (at present Samara Polytechnic University). Impact sensitivity tests are performed to determine the relative sensitivity of solid, liquid and paste materials on an impact device with 10 and 2kg weights that drop vertically (Fig.1). The maximum drop height for 10 kg weights is 0.5 m and for 2 kg weights is 1.0 m.

Fig.1 Schemes of roller drop weight machines forimpact sensitivity tests

The measured impact sensitivity parameters:

LL:impact sensitivity lower limit for solid explosives on Devices 1 and 2. It is evaluated from the maximum drop height of a 10 or 2 kg weight per a test specimen with the mass (0.100 ± 0.005) g, at which no explosion occurs in 25 tests;

Ad1,Ad2:explosion frequency for solids on Devices 1 and 2 (only for explosives with the impact sensitivity lower limit 50 mm and higher for a 10 kg weight). It is evaluated from the number of explosions in 25 tests for a 10 or 2kg weight per a test specimen with the mass (0.050±0.005)g dropped from the 250 mm height;

A50 d1,A50 d2:height, at which explosion occurs with 50% probability on Devices 1 and 2 (for solid energetic materials). It is calculated from a drop height-explosion frequency curve.

For the joint account of the data obtained during dumping loads weighing 2kg and 10kg, the results are considered as multiplying the drop height of load and its mass.

An explosion is defined as an explosive transformation accompanied by a sound effect or flame, or burn marks on the rollers or coupling of the machine. The substance′s color change is disregarded. Explosion frequency is a relative number of explosions over 25 tests of specimens compressed under the preset pressure between two steel planes at shock shift. Plastic deformation of red-hot rollers is observed where a 10kg weight drops from a height above 0.5m. Therefore it is determined by extrapolation to 50% explosion frequency for energetic materials whose 50% probability initiation height exceeds 0.5m.

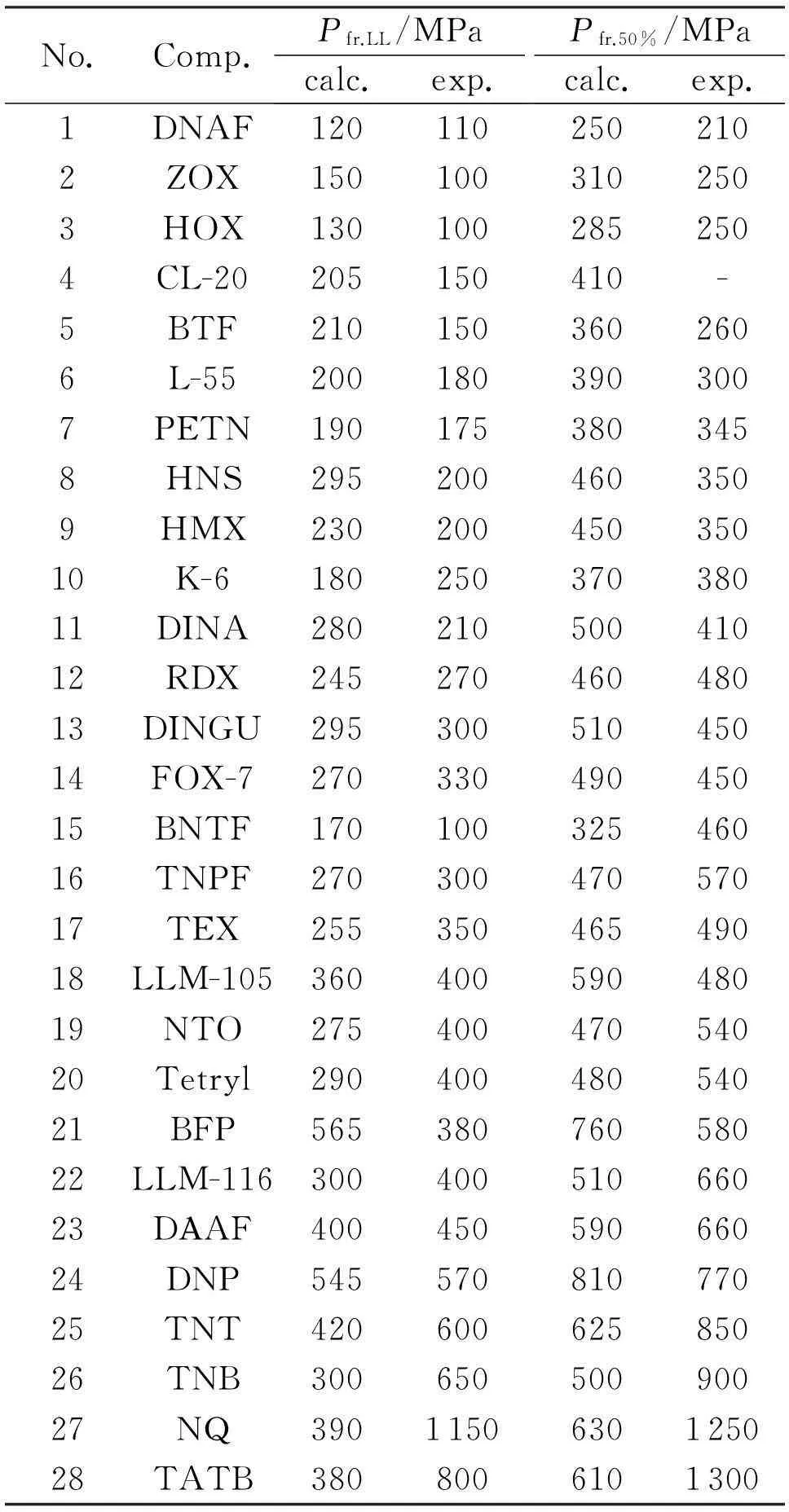

Table 1 shows impact sensitivity values measured experimentally for a number of explosives from different chemical classes. Description of the methods for calculations of sensitivity parameters is presented below.

Table 1 Impact sensitivity parameters of some explosives

Table 1 (Continued)

Note:1-DNAF 4,4′-dinitro-azofuroxan[22]; 2-HNB hexanitrobenzene[23]; 3-ZOX bis(2,2,2-trinitroethyl-n-nitro)ethylenediamine[24]; 4-PETN pentaerythritol tetranitrate; 5-CL-20 hexanitrohexaazaisowurtzitane[25]; 6-Sorguil 1,3,4,6-tetranitroglycoluril[26]; 7-L-55 2,4,6,8-tetranitro-2,4,6,8-tetraazabicyclo(3.3.0)octane[27]; 8-K-6 2-oxo-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazacyclohexane[28]; 9-BTF benzotrifuroxan[29]; 10-HOX bis(2,2,2-trinitroethyl)nitramine[30-31]; 11-HMX cyclotetramethylene tetranitramine; 12-BNTF 3,4-bis (4-nitrofurazan-3-yl) furazan[32]; 13-RDX cyclotrimethylenetrinitramine; 14-HNS 2,2′,4,4′,6,6′-hexanitrostilbene; 15-Tetryl 2,4,6-trinitrophenylmethylnitramine; 16-TNPF trinitropropylnitrofuroxanyl[33]; 17-TNAZ 1,3,3-trinitroazetidine[34]; 18-BFP bifurazanilpiperazine[35-36]; 19-LLM-105 2,6-diamino-3,5-dinitropyrazine-1-oxide[37]; 20-TEX 4,10-dinitro-2,6,8,12-tetraoxa-4,10-diazatetracyclo-(5.5.0.05,9 03,11)dodecane[38]; 21-TNB 1,3,5-trinitrobenzene; 22-DAAF 3,3′-diamino-4,4′-azoxyfurazan[39]; 23-NTO 3-nitro-1,2,4-triazole-5-one[38]; 24-FOX-7 1,1-diamino-2,2-dinitro-ethylene[38]; 25-LLM-116 3,5-dinitro-4-aminopyrazole[37]; 26-DINGU dinitroglycoluril; 27-DINA nitrodiethanolamine dinitrate; 28-DNP 1,4-dinitropiperazine[40]; 29-TNT 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene; 30-NQ nitroguanidine; 31-TATB 1,3,5-triamino-2,4,6-trinitrobenzene.

It is commonly supposed that an energy buildup in a molecule leads to a higher risk. Let us see whether this is consistent with impact sensitivity testing data. The tabulated substances can be conventionally split to 4 groups by sensitivity: (1)more sensitive than PETN (comp.1-3); (2)comparable with PETN (comp.4-10); (3)comparable with HMX (comp.11-28); (4)comparable with TNT (comp.29-31).

No questions arise regarding the assignment of the explosives to groups 1 and 2 whereas group 3 is rather controversial. For example, in accordance with the impact sensitivity values group 3 includes both TNAZ and TEX, although the explosion heat of TNAZ is 1.5-fold higher than that of TEX. Reasoning for such low selectivity of drop weight tests will be given below, after a joint discussion of impact sensitivity and friction sensitivity parameters and detonability.

Device 1 has a small linear size (roller Φ10mm) that restricts the motion of a specimen in the plane perpendicular to the impact line. Device 2 was designed by Kholevo[15]with a view to provide more room for the motion and is capable of a more correct simulation of the molecule′s behavior at impact and does not limit its moving sideways from under the striking surface. Noteworthy is that impact sensitivity values for low-melting substances obtained on Device 1, as a rule, are higher than those measured on Device 2 whereas impact sensitivity parameters for higher melting substances with strong crystals on Device 1 are normally lower relative to same characteristics obtained from Device 2.

The set of compounds under our consideration represents various classes of organic compounds and therefore drop weight test results only qualitative conclusions concerning the influence of individual functional groups of atoms or particular atoms on impact sensitivity. Below we will elaborate at a reason why available data is not reliable enough to judge on a functional relationship between the molecular structure and impact sensitivity.

2Friction Sensitivity Tests

Russia has special regulations that establish a standard for testing of the energetic materials friction sensitivity (friction sensitivity) at shock shift. It is a small-scale impact friction test for powder, granulated, elastic, cast, pressed, and paste energetic materials. A roller machine used here is similar to Device 1 for impact sensitivity tests differing in the impact direction-vertical onto the roller in impact sensitivity tests and horizontal onto the test piece under pressure (p) in friction sensitivity tests (Fig. 2). In operation, the coupling goes down approximately to the center of the bottom roller to ensure a free lateral displacement under impact (Fig.2). The test specimen mass is (0.020+0.002)g.

Fig.2 Scheme of the roller machine ready for the sideimpact on the test piece in a friction sensitivity test

The measured friction sensitivity parameters:

Pfr.LL:friction sensitivity lower limit (basic parameter) that corresponds to the maximum pressure applied to the test specimen (2, Fig.2), at which no explosion occurs in 25 tests at a shock shift of one plane relative to the other at the 1.5mm distance.

Pfr.50%:50% probability initiation pressure calculated from a pressure-explosion frequency curve.

To ensure the constant velocity and value of the top roller shift relative to the bottom roller, a drop angle of the pendulum that strikes the top roller is set depending on the jam pressure of the specimen. The pressure varies in a range from 30 to 1200MPa.

Table 2 shows the friction sensitivity values obtained experimentally for a number of compounds from different chemical classes. Here the substances in group 1 and 2 differ sequentially from those in Table 1, however even the addition of group 5 does not allow an assignment of TNPF and TEX, because in accordance with features of the experimental determination, which basically correspond to effects during technological processing TNPF TEX, they fall under the same group by handling risk.

Drop weight tests were not actually intended for any categorization of explosives by their handling risk. In industry, they are trivially divided to two groups in terms of their permissibility for a particular process-whether they are operable in pressing or not, permitted for ball mill grinding or not, etc. For that, limiting values of each impact sensitivity and friction sensitivity parameters were approved and specified in standard manufacturing procedures. For instance, to undergo pressing the substance′s friction sensitivity lower limit (PfrL) has to be minimum 200 MPa, no matter how higher this value is. Accordingly, the required accuracy of impact sensitivity and friction sensitivity parameter measurements relies on these. In practice, the accuracy is not very high. Low reproducibility of drop weight test results for TNT was shown in[3]. The drop height, corresponding to 50% explosion frequency, was found as 100-250cm in different sets of tests for double- crystallization TNT. Such dispersion of data is usually attributed to the methodological specificity, particle size distribution, air humidity, etc. Thus drop weight test results cannot be utilized for a precise estimation of the energetic material response to various impacts and low selectivity is the most significant disadvantage of the tests.

Table 2 Friction sensitivity parameters of some explosives

The tabulated compounds (for full forms see Table 1) can be conventionally split to 5 groups by sensitivity: (1)more sensitive than PETN (comp.1-6); (2)comparable with PETN (comp.7); (3)comparable with HMX (comp.8-12); (4)comparable with TNT (comp.13-25); (5)less sensitive than TNT (comp.26-27).

Meanwhile one should not underestimate the value of these tests since they had allowed a number of suppositions on the detonation process emergence and development, which in turn gave an impetus to the evolvement of the detonation theory for condensed explosives. These particular tests revealed an essential decrease in the impact and friction sensitivity due to the use of phlegmatizers. Furthermore, they provided the substantiated key parameters for munition loading with high performance RDX and HMX formulations. In addition, they allow certain ranking of high explosives by risk in handling and for the selection of process conditions in manufacturing of energetic materials, which is fairly satisfactory for most

operations.

3Systemization of Experimental Results

3.1Equations for Sensitivity Parameters Evaluation

In this work, we used our experimental data on the energetic materials sensitivity to external factors and findings of Semenov Institute of Chemical Physics of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Samara State Technical University, St.-Petersburg Technical University, and some other research centers.

Equations for a relation between the explosive parameters and the chemical composition and structure of a molecule were derived on the regressive analysis basis. The most significant parameters were singled out by “inclusion-exclusion” and stepwise regression methods to afford interpolation dependencies. Apart from that, inapplicable experimental data was rejected. We did not account for an effect of particle sizes and shape due to insufficient data. Of note is that, in most cases (52% of the substances we examined), the particle size was in a range of ~100-300μm and, moreover, the fineness of 14 substances was 50μm and less and of 5 substance -400μm and more. Particle size data for 48 molecules was unavailable. Despite that the dispersity effect is meaningful, it is not determinant in valuing the impact sensitivity, as was shown by our computations. The number of the rejected statistics in the analysis of each parameter did not exceed 10% of the initial data body.

Previously, a method of atomic contributions[41]was implemented to calculate impact sensitivity and friction sensitivity parameters[42]. It builds on an assumption on the additivity and transferability (from one molecule to the other) of explosive parameters in relation to contributions of the finite number of atoms incorporated in the starting molecule. Atoms are assigned to different types in accordance with their pertinence to functional groups. 35 types of atomic contributions were sorted out for C,H,N, O-containing compounds, including three types for carbon atoms -C1, C2, C3, twelve for nitrogen atoms -N1, N2… . N12, fourteen for oxygen -O1, O3…. O14, and for atoms of hydrogen, fluorine, bromine, and chlorine-one type each. This approach was developed by Prof. S.P. Smirnov (Dzerzhinsk Chemical and Technological Research Institute, Russia) to calculate the monocrystal density, detonation velocity and enthalpy of formation. Further on it was enhanced by his fellow researchers with a view to estimate the external impact sensitivity and some other energetic parameters of individual explosives.

We used Smirnov′s method to calculate the monocrystal density and enthalpy of formation[41, 42], elaborated on its shortcomings with respect to impact sensitivity and friction sensitivity that could lead to false cause-and-effect relationships. Here we highlight a few major irrelevances of the method.

To develop computational methods for the density and enthalpy of formation of molecules we made up a dataset of 1000 parameters sourced from data on the properties both of explosive and of non-explosives. Basically, data on explosives would be sufficient to design computational schemas for explosive properties. However, due to relatively scarce data on compounds of some chemical classes and differences in approaches to estimating impact sensitivity and friction sensitivity, evaluations of contributions from different atom types dramatically differ in accuracy. Given that, we considered impact sensitivity and friction sensitivity parameters as functions of gross ratios of chemical elements, the energy content, density, and other integral properties of the chemical composition and structure.

The equations for explosive sensitivity calculations were derived on the basis of the available data analysis. The key parameters responsible for the insensitivity of molecules to external impact included the monocrystal density (ρ, g/cm3), gross sum (B, quantity of gram-atoms of chemical elements in a kilogram of a substance, g-atom/kg), maximum heat of explosion (Qmax, kcal/kg), oxidizer excess coefficient (α), and melting point (Mp).

Below are given the equations for calculating the impact sensitivity and friction sensitivity parameters along with statistical indicators and parameters from the datasets.

Explosion frequency (Ad1) in Device 1 varied in the range of 0-100; the number of tests was 119, the average deviation -9.08, dispersion - 553, and the correlation factor -0.971:

Ad1=(ρ·B)-1.270Qmax2.801α1.380(500-Mp)-1.644[%]

(1)

Explosion frequency (Ad2) in Device 2 varied in the range of 0-100; the number of tests was 112, average deviation -16.03, dispersion -851, and the correlation factor -0.941:

Ad2=(ρ·Qmax)2.786α0.9801(500-Mp)-3.134[%]

(2)

The impact sensitivity low limit (LL) varied in the range of 0.1-5.0; the number of tests was 110, average deviation -1.03, dispersion -3.04, and the correlation factor -0.989:

LL=0.1(ρ·B/Qmax)1.699α-1.013(500-Mp)1.351[kg·m]

(3)

The 50%-probability initiation height (A50 (d1)) in Device 1 varied in the range of 0.27-11.5; the number of tests was 120, average deviation -0.23, dispersion -2.49, and the correlation factor -0.994:

A50 (d1)=0.01(ρ·B)1.617(α·Qmax)-0.9022(500-Mp)0.565[kg·m]

(4)

The 50%-probability initiation height (A50 (d1)) in Device 2 varied in the range of 0.27-14.0; the number of tests was 103, average deviation -0.40, dispersion -4.28, and the correlation factor -0.990:

A50(d1)=0.01(ρ·B)0.8902(α·Qmax)-0.9383(500-Mp)1.218[kg·m]

(5)

The friction sensitivity low limit (Pfr LL) varied in the range of 500-11,500; the number of tests was 136, average deviation -182, dispersion -2.21×106, and the correlation factor -0.999:

Pfr LL=(ρ·B)1.616(α·Qmax0.5)-0.8618(500-Mp)0.4016[kgf·m2]

(6)

The 50%-probability initiation pressure (Pfr.50%) varied in the range of 1700-3000; the number of tests was 110, average deviation -102, dispersion -2.12×106, and the correlation factor -0.999:

Pfr.50%=(ρ·B)1.647(α·Qmax0.5)-0.5646(500-Mp)0.3138[kgf·m2]

(7)

In Tables 1 and 2 the calculated (equation 1-7) data are compared with the experimental results for compounds of different classes over the entire range of experimental characteristics.

3.2Analysis of the Statistic Models

Quite difficult to choose the appropriate coordinates for graphical analysis of the calculated dependences we obtained. This is primarily due to the strong pair correlation of all the main parameters of the initial compound. Such a correlation can often result in false conclusions about cause and effect relationships between the characteristics of explosives. That′s why for the graphical representation of dependencies, we used the combined parameters similar to those obtained by us for the regression equations (1-7). As coordinates on the x-axis we used the multiplication of the density of matter and of the gross amount (ρ·B), on the y-axis we selected the multiplication of the oxidizer excess coefficient and the maximum heat of explosion, and on the z-axis the parameter of sensitivity was used. The multiplicationα·Qmaxis considered by us as a characteristic of the maximum energy capacity of the reacting layer of explosive, and the value ofρ·Bis seen as a characteristic defining difficulties for heating of initiated layer.

Figure 3 shows the isolines of the explosion frequency in the device 1 (Ad1) along the axesρ·B-α·Qmax.

Fig.3 Isolines of the explosion frequency at the device1(Ad1) in the axes ρ·B-α·Qmax

The analysis of the diagram shows that up to the value of 1000 on thex-axis the frequency of explosions at the device 1 decreases with increasing of theρ·Bvalues. After the value of 1000 the relative frequency is almost independent of the multiplicationρ·B. However, it should be remembered that the accuracy of the experimental determination ofAd1can not be higher than 8%. The surface passing through the isolines of Figure 3 can be conditionally considered as the “middle” of the bulk region ofAd1points. Although Figure 3 reflects some general trend of joint influence ofρ·Bandα·Qmax, but more correctly their influence should be considered taking into account the energy loss of a possible phase transition.

Figure 4 shows the isolines of height for 50% probabilities of triggering at the device 1 in the axesρ·B-α·Qmax. Height of 50% probability of triggering is a more statistically reliable parameter of sensitivity than others. The combined influence ofρ·B-α·Qmaxis adequately traced on all the graphic space. However, as in the case of Figure 3, here we also should not forget that the surface passing through the isolines is the “middle” of the space of points, and the diagram does not take into account the effect of the phase transition.

Fig.4 Isolines of height for 50% probabilities of triggering atthe device 1 (Ad1) in the axes ρ·B-α·Qmax

Figure 5 shows the isolines of pressure for 50% probability of response when tests for sensitivity to friction under shock shift (Pfr.50%) in axesρ·B-α·Qmax.

Fig.5 Isolines of pressure for 50% probability(Pfr.50%) in the axes ρ·B-α·Qmax

In our opinion, the pressure of 50% probability of response when tested for sensitivity to friction under shock shift (Pfr.50%) is the most accurate and statistically reliable parameter of all the indicators defined in the drop weight machines. The relative height of the space of points at this diagram is the lowest in comparison with the diagrams of Fig. 3 and 4.

As follows from equations 1-7, the impact of the phase transition loss forPfr.50%is the smallest here. That is why the relationship of friction sensitivity with energy content of the reacting layer (α·Qmax) and the inputs for heating of initiated layer (ρ·B) is the most clearly presented in Figure 5. A distinctive feature of the interpolation Equations (1-7) for the impact sensitivity and friction sensitivity characterization is that the melting point (Mp) is regarded to be an essential factor. Under a relatively slow impact inherent to drop weight tests, substances withMpbelow 100℃ start melting, which negatively tells on the resulting risk assessment based on the impact sensitivity and friction sensitivity parameters. That is why the well-known powerful fusible explosive trinitroazetidine (TNAZ), by its impact sensitivity and friction sensitivity test results, can be attributed to low sensitivity substances.

Also, for explosives withMpabove 200℃ (such as nitrotriazolone (NTO) or bifurazanilpiperazine (BFP)), the impact sensitivity and friction sensitivity values tend to be understated: e.g. the frequency value for BFP (Device 1) is 48%, which is close to Tetryl. For NTO (Device 2) -84%, it corresponds to the PETN level. BFP and NTO-type explosives have a relatively high susceptibility to impact and at the same time do not enhance the excitation focus development onto the surrounding explosive mass.

It is clear that the explosion excitation and hence the sensitivity of explosives in general should be governed both by thermodynamic and by kinetic factors. The above Equations relate solely to the thermodynamics of explosion. TheMpeffect on the sensitivity is more likely to depend on the fact that anMprise is caused by a higher strength of the intermolecular bonds and therefore by a higher thermodynamic stability. Thus the obtained results point out a decisive role of the thermodynamic factor in the explosion initiation. Note that the importance of this factor was mentioned earlier in[43]. Meanwhile it is impossible to completely deny the kinetic factor′s role in the process. It is known that e.g. organic azides, having approximately the same energy content as nitro compounds, are characteristic of a much higher sensitivity, which could be related to the special kinetics of the azide decomposition in “hot spots”.

4Conclusions

The laboratory methodologies utilized in Russia to measure the impact and friction sensitivity of high energy materials in terms of operational risk assessment have been described.

The computational methods for the key sensitivity parameters have been developed on the basis of drop weight test results for several explosives that represent different classes of C,H,N,O-containing organic molecules. The analysis of the datasets allowed the identification of the major processes that determine a safety level of high energy materials as well as, inter alia, the quantification of the effect of their melting on sensitivity values through the account of melting points. At a relatively slow impact inherent to drop weight tests, substances with melting points below ~100℃ partly melt on the outer surface of particles in contact points, which distorts safety assessment results based on the impact sensitivity.

Explosion frequency values adequately characterize operational risk. According to Equation 1 and 2, the 10% buildup of the energy content (Qmax) increases risk of explosive handling by 30%, i.e. a rise in risk dramatically outruns a rise in capacity.

Drop weight tests for the explosive sensitivity will be practiced for a long time ahead, despite their relatively low accuracy, primarily because these have been stipulated in Russian regulations on the commercial synthesis of explosive formulations and manufacture of munition charges.

A distinctive feature of the parameters yielded by drop weight tests is that they are appreciably affected by the melting process, which is responsible for low selectivity in testing of fusible explosives capable of melting at a slow impact or low sensitivity explosives that have a low capacity of the propagation from the source to the surrounding mass. However there is a large scope of formulations that incorporate neither fusible nor low explosives, for which drop weight tests remain relevant.

Reference:

[1]Kamlet M J. The relationship of impact sensitivity with structure of organic high explosives. Part I. polynitroaliphatic explosives∥ Process of the 6th Symposium (International) on Detonation, Report # ACR 221. Washington D C: Office of Naval Research, 1976:312-322.

[2]Keshavarz M H, Pouretedal H R, Semnani A. Novel correlation for predicting impact sensitivity of nitroheterocyclic energetic molecules[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2007 (141) :803-807.

[3]Kamlet M J, Adolph H G. The relationship of impact sensitivity with structure of organic high explosives. Part II. Polynitroaromatic Explosives[J]. Propellants, Explosives, Pyrotechnics, 1979(4):30-34.

[4]Storm C B, Stine J R, Kramer J F. Sensitivity relationships in energetic materials in chemistry and physica of energetic materials[J]. NATO ASI Series C, 1990, 309:605-639.

[5]Sharma J, Beard B C, Chaykovsky M. Correlation of impact sensitivity with electronic levels and structure of molecules[J]. J Phys Chem, 1991, 95:1209-1213.

[6]Politzer P, Murray J S, Lane P, et al. Shock-sensitivity relationships for nitramines and nitroaliphatics[J]. Chem, Phys, Lett, 1991, 181:78-82.

[7]Cooper P W. Explosives Engineering[M]. New York: Wiley-VCH, 1996:312.

[8]Zeman S, Krupka M. Study of the impact reactivity of polynitro compounds, Part I: Impact sensitivity as "The First Reaction" of polynitroarenes[C]∥Proc of the 5th Seminar on New Trends in Research of Energetic Materials. Pardubice:[s.n.], 2002:407-415.

[9]Akhavan J. The Chemistry of Explosives[M]. 2nd ed. Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry, 2004.

[10]Rice B M, Byrd E F C. Theoretical chemical characterization of energetic materials[J] J Mater Res, 2006, 21:2444-2452.

[11] Alouaamari M, Lefebvre M H, Perneel C, et al. Statistical assessment methods for the sensitivity of energetic materials[J]. Propellants, Explosives, Pyrotechnics, 2008, 33 (1):60-65.

[12]Keshavarz M H. Simple Relationship for predicting impact sensitivity of nitroaromatics, nitramines, and nitroaliphatics[J]. Propellants, Explosives, Pyrotechnics, 2010, 35: 175-181.

[13] Mathieu D. Toward a physically based quantitative modeling of impact sensitivities[J]. Journal of Physical Chemistry, 2013:2253-2259.

[14]Recommendations on the Transportation of Dangerous Cargoes, Management and Criteria of Tests, (ST/SG/AC.10/11/Rev. 4)[S]. New York: [s.n.]2003.

[15]Kholevo N A. Impact Sensitivity of Explosives (Russ.)[M]. Moscow: Mechanical Engineering, 1974: 135.

[16]Khariton Y B. Theory of Explosives (Russ.)[M]. Moscow: GNTI OBORONGIZ, 1940:270.

[17]Andreev K К, Belyaev A F. Theory of Explosives (Russ.)[M]. Moscow:GNTI OBORONGIZ, 1960:595.

[18]Bolkhovitinov L G. Relation between the impact sensitivity of explosive materials and the flash point[J]. Zhurnal Fizicheskoi Khimii (Russ.), 1960, 34:476-484.

[19]Merzhanov A G, Barzykin V V, Gontovskaya V T. The problem of a local thermal explosion[J]. Doklady Akademii Nauk SSSR (Russ.), 1963, 148:380-388.

[20]Afanas’ev G T, Bobolev V К. Initiation of Solid Explosives by Impact (Russ.) [M]. Moscow: Nauka, 1968:120.

[21]DubovikА V. Thermal instability of the axial deformation of a plastic layer and evaluation of the critical pressure for the shock initiation of the detonation of solid explosives[J]. Fizika Goreniya i Vzryva (Russ.), 1980, 16(4):103-109.

[22]Talawar M B, Sivabalan R, Mukundan T. Environmentally compatible next generation green energetic materials (GEMs) [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2009 (161):589-607.

[23]Nielsen A T, Atkins R L, Norris W P,et al. Synthesis of polynitro compounds. Peroxydisulfuric acid oxidation of polynitroarylamines to polynitro aromatics[J]. Journal of Organic Chemistry, 1980, 45(12):2341-2347.

[24] Dong H S. Properties of bis(2,2,2-trinitroethyl-n-nitro)-ethylendiamine and formulations of them∥ Proc of the 9-th International Symposium on Detonation. Portland:[s.n.],1989:112-124.

[25]Willer R. The true history of CL-20∥ Proc of the 16th Seminar on “New Trends in Research of Energetic Materials” [J]. Pardubice:[s.n.],2013:384-397.

[26] Boileau J, Carail M, Wimmer E, et al.Derives nitres acetyles du glycolurile[J]. Propellants, Explosives, Pyrotechnics, 1985, 10 :118-120.

[27]Wu X, Sun J, Xiao L J. The detonation parameters of new powerful explosive compounds predicted with a revised VLW equation of state[C]∥Proc of the 9th International Symposium on Detonation. Portland:[s.n.], 1989:245-259.

[28] Mitchell A R, Pagoria P F, Coon C L. Nitroureas: synthesis, scale-up and characterization of K-6[J].Propellants, Explosives, Pyrotechnics, 1994, 19: 232-239.

[29] Dobratz B M. Properties of Chemical Explosives & Explosive Simulants, Explosive Handbook[M]. Livermore: University of California, 1981:528.

[30] Kustova L V, Kirpichev E P, Rubtsov Y I, et al.Standard enthalpies of formation of some nitro compounds[J]. Izvestiya Akademii Nauk SSSR, Seriya Khimicheskaya (Russ.), 1981, 10:2232-2238.

[31] Yan Hong, Gao X P, Chen B R. Comparison of thermal stabilities of azidomethyl-gem-dinitromethyl compounds[C]∥ Proc of the 21st Int Pyrotechnics Seminar. Moscow:[s.n.], 1995:312-315.

[32] Astratiev A A, Melnikova S F, Dushenok S A, et al. Investigation of properties of NTF - new meltable HE[C]∥ Proc of the International Conference of Shock Waves in Condensed Matter. Kiev:[s.n.],2012: 380-387.

[33]Mikhailov A L, Vasipenko S A, Vakhmistrov S A,et al. Research of properties of powerful cast explosives TNAZ and TNPF-2[C]∥ Proc of the 9th Kharitonovsky Thematic Scientific Readings (Russ.). Sarov: RFJATS-VNIIEF, 2007:182-186.

[34] Stinecipher M M. Heat of formation determinations of nitroheterocycles[C]∥ Proc of the 49th Calorimeters Conference. Santa Fe:[s.n.], 1994:124-136.

[35] Sheremetev A B, Kulagina V O, Batog L V, et al. Furazan derivatives: High energetic materials from diaminofurazan[C]∥ Proc of the 22nd International Pyrotechnics Seminar. Fort Collins:[s.n.],1996:254-266.

[36] Voronko O V, Smirnov A S, Terent’yev A B, et al. Heat of explosive transformation of insensitive explosives and their mixtures with high explosives[C]∥Proc of the Conference “Combustion and explosion” (Russ.). Frolov: Тоrus Press, 2013:288-292.

[37] Pagoria P F, Lee G S, Mitchell A R, et al. The synthesis of amino- and nitro-substituted heterocycles as insensitive energetic materials[C]∥Proc “Insensitive Munitions & Energetic Materials”. Technical Symposium. Bordeaux:[s.n.], 2001:655-661.

[38]Badgujar D M, Talawar M B, Asthana S N, et al.Advances in science and technology of modern energetic materials: An overview[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2008 (151):289-305.

[39] Chavez D, Hill L, Hiskey M,et al. Preparation and explosive properties of azo- and azoxy-furazans[J]. Journal of Energetic Materials, 2000, 18(2/3):219-236.

[40] Pepekin V I, Makhov M N, Lebedev Y A.Heats of explosive decomposition of individual explosives[J]. Doklady Akademii Nauk SSSR (in Russian), 1977, 232(4):852-855.

[41] Smirnov A, Smirnov S, Pivina T, et al. The influence of calculation accuracy of formation enthalpy and monocrystal density estimations on some target parameters for energetic materials[C]∥ Proc of the 15th Seminar on “New Trends in Research of Energetic Materials”. Pardubice:[s.n.], 2012:280-291.

[42] Smirnov A S, Khvorov F T, Karachev A G. Development of calculation methods to estimate the sensitivity of explosives to shock and friction[C]∥ Proc “XI Haritonovsky Thematic Scientific Readings” (Russ.). Sarov:RFJATS-VNIIEF, 2009:89-95.

[43]Pepekin V I, Korsunskii B L, Denisaev A A. Excitation of explosion of solid explosives at mechanical effect[J]. Fizika Goreniya i Vzryva (Russ.), 2008, 44(5):101-105.

DOI:10.14077/j.issn.1007-7812.2015.03.001