转基因油菜与野芥菜混作对土壤线虫群落的影响

肖能文, 刘勇波, 陈群英, 付梦娣, 叶 瑶, 李俊生,*

1 中国环境科学研究院, 环境基准与风险评估国家重点实验室, 北京 100012 2 中国科学院动物研究所, 农业虫鼠害综合治理研究国家重点实验室, 北京 100080

转基因油菜与野芥菜混作对土壤线虫群落的影响

肖能文1, 刘勇波1, 陈群英2, 付梦娣1, 叶 瑶1, 李俊生1,*

1 中国环境科学研究院, 环境基准与风险评估国家重点实验室, 北京 100012 2 中国科学院动物研究所, 农业虫鼠害综合治理研究国家重点实验室, 北京 100080

随着转基因作物在全球的广泛种植,转基因作物对非靶标生物的影响受到人们的广泛关注。转Bt基因抗虫作物与非转基因作物种间混作是避免昆虫产生抗性的一种生态防御策略,但混作对非靶标生物尤其是土壤线虫影响研究较少。设置不同比例的转基因油菜(Brassicanapus)与野芥菜(B.juncea)混作5种处理,包括处理A、B、C、D、E分别为转基因油菜和野芥菜比例0∶100;25∶75;50∶50;75∶25;100∶0,调查不同生育期土壤线虫种类与数量变化。结果表明,在油菜与野芥菜生育期内,不同处理线虫优势类群均为拟丽突属Acrobeloides和真滑刃属Aphelenchus,各处理线虫属数由多到少顺序为处理B(30属)>处理C(28属)>处理A(26属)>处理D和处理E(25属)。线虫生活史策略(c-p值)组成一致,各处理间线虫生活史组成不存在明显差异。不同处理的线虫总数以及各营养类群均无显著差异,线虫群落生态指数亦无显著差异,但不同采样时期间线虫Shannon-Wiener多样性指数、Simpson优势度指数、均匀度指数、成熟度指数和线虫通路指数差异显著。结果表明转基因油菜与野芥菜单作和混作短期内不影响土壤线虫群落结构。

转基因油菜; 野芥菜; 种间混作; 土壤线虫; 群落结构

随着转基因作物在全球的广泛种植[1],靶标昆虫对抗虫基因的适应以及次生害虫的爆发成为转基因作物安全性评价的重要内容[2]。通常用种内混作或者建立避难所来延缓靶标害虫抗性的产生[3-4]。转基因作物种子与非转基因种内混作因为容易操作,被推荐为昆虫减小或者避免抗性产生的一种策略[5]。不同品种作物间按不同行相间种植的“种间混作”模式可提高光能和土地的利用率,达到稳产保收,同时能改变害虫与天敌群落结构[6],成为一种在中国常见的耕作模式[7]。

线虫是土壤动物区系中最为丰富的无脊椎动物,其营养类群多样,在土壤食物网中占有重要位置[8]。线虫具有培养分离鉴定相对简便、敏感性良好、以及对环境变化能做出迅速反应等特点。线虫群落研究发展相对成熟的计算方法,如成熟度指数(MI)能直接地反映线虫群落的演替状态,敏感地反映土壤环境的受胁迫程度[9]。线虫通路指数(NCR)能表示土壤有机质的分解途径[10],因此常被广泛地应用于土壤质量以及土壤污染的研究[11-12]。

自1986年Mathew等首先将新霉素磷酸转移酶(neomycin phosphotransferase gene,NPT-Ⅱ)基因利用农杆菌介导法转入芥菜型油菜以来,开始对包括从细菌Bacillusthuringiensis[Berliner](Bt)获得的转基因油菜进行种植与研究[13]。转Bt油菜能有效控制小菜蛾PlutellaxylostellaL.和美洲棉铃虫HelicoverpazeaBoddie[14]。但转基因油菜也存在一定安全风险。如转Bt油菜花粉逃逸能与野芥菜Brassicarapa杂交。Burgio等认为转基因油菜Bt蛋白能残留在非靶标昆虫桃蚜Myzuspersicae体内[15]。但Pierre等认为转基因油菜对4种蜜蜂无显著影响[16]。Howald等在油菜叶蜂Athaliarosae体内检测到Bt蛋白,但是对其生活史没有影响[17]。

Bt毒素能通过花粉、作物残体以及根分泌物进入土壤环境[18-19],可能对土壤环境以及土壤生物产生潜在风险,因此转基因作物是否影响土壤生物多样性及群落结构受到社会广泛关注[7, 20]。Zwahlen等用转基因玉米喂食蚯蚓Lumbricusterrestris200 d后,蚯蚓体重显著减少[19]。转基因作物对线虫影响也有广泛报道。某些Bt蛋白,如Cry5B、Cry6A、Cry14A和Cry21A发现对某些线虫有直接毒性[21]。但Yang等调查了连续种植转基因棉田土壤线虫,并认为无明显影响[7],Höss等也认为转基因玉米对土壤自由生活线虫无显著影响[20]。转基因作物与常规物种“种间混作”常改变农田害虫与天敌群落结构,因此需要对转基因作物生态安全进行进一步研究,但转基因油菜与野芥菜之间混作是否影响土壤线虫群落结构的研究未见报道。

本文选择转基因油菜与野芥菜为研究对象,按照不同比例移栽转基因油菜与野芥菜幼苗,在不同时期对土壤进行采样,调查转基因油菜与野芥菜种间混作对线虫群落结构的影响,以期更全面地了解转基因油菜与其他植物混作对非靶标土壤动物的影响,为转基因油菜的潜在非靶标生物生态风险评价提供科学依据。

1 材料与方法

1.1 实验材料

野芥菜(Brassicajuncea, 2n= 36, AABB)为十字花科植物,是油菜(Brassicanapuscv “Westar”, 2n=38, AACC)的近缘种,可与油菜进行杂交,种子由南京农业大学提供,从当地田间收集[22]。转基因油菜为 pSAM 12质粒转化,包含CaMV 35S启动子控制编码绿色荧光蛋白(Green fluorescent protein, GFP)和Bt(Bacillusthuringiensis) Cry1Ac蛋白基因油菜[23]。

1.2 实验处理

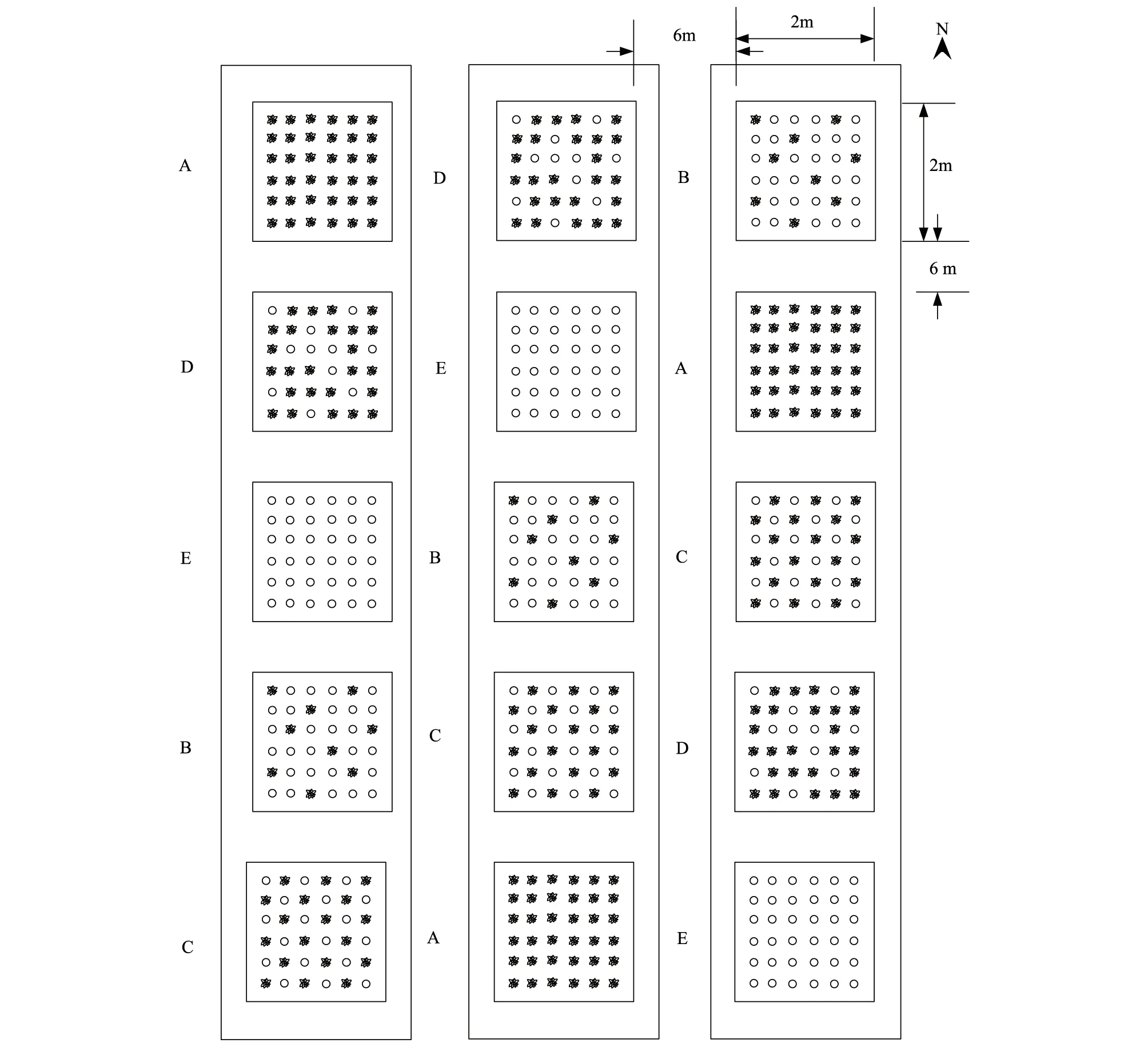

实验在北京顺义实验基地进行,按照随机区组设计3个平行小区,每小区完全随机设置转基因油菜和野芥菜按照0∶100(处理A);25∶75(处理B);50∶50(处理C);75∶25(处理D);100∶0(处理E)不同比例5个处理。处理设置在2 m×2 m×2 m的50目尼龙网纱罩中,处理间距离6 m。转基因油菜和野芥菜按比例相间排列,种植密度为6×6株(图1)。转基因油菜和野芥菜2012年4月16日温室播种,5月20日移栽至试验地。每处理移栽灌溉以及杂草处理实行一致的管理方法,全生育期不施药。

于2012年移栽前(5月20日),以及移栽后按照生育期花期(7月4日)和收获期(8月14日)分别采样。在样方内选择3个点取土,用土钻采集深度为0—10 cm的表土,将其均匀混合后制成约500 mL混合土样带回实验室分离线虫和进行理化分析。土壤pH值为7.3±0.5,有机碳含量为(6.8±0.4)mg/g。

1.3 线虫分离、鉴定

每个土样取土100 cm3,3 d内用改进的Baermann漏斗法分离线虫48 h[24],收集线虫悬浮液并浓缩至2 mL,用4%福尔马林溶液固定。光学显微镜下参照Goodey的分类系统[25]和《中国土壤动物检索图鉴》[26]以及《植物线虫志》[27],将线虫鉴定到属,并统计各属线虫数量。

图1 转基因油菜与野芥菜单作以及混作实验设计布局图Fig.1 Experimental design layout for sole cropping or mixed intercropping between transgenic oilseed rape and wild mustard

1.4 线虫群落结构分析

土壤线虫依据Yeates等分为4个营养类型[10],分别为食细菌类(Ba)、食真菌类(Fu)、植物寄生类(PP)和杂食捕食类(OP)。根据线虫不同的生活史策略,将线虫划分为5个类群,即不同的colonizer persister (c-p)类群[28]。

研究采用生态学评价指数:Shannon-Wiener多样性指数H′,H′=-∑PilnPi,Pi=ni/N,式中Pi为样品中属于第i种的个体的比例;ni为第i类群的个体数;N为所有类群的个体总数[29]。Pielou均匀度指数J′,J′=H′/lnS,式中S为类群数[30]。Simpson优势度指数λ,λ=∑(ni/N)2,λ=∑H′2[31]。线虫成熟指数,MI=∑v(i)f(i),式中v(i)是第i种线虫的c-p值;f(i)第i种线虫的个体数占自由生活线虫数量的比例[9]。线虫通路比值(NCR),NCR=NBa/(NBa+NFu),式中NBa为食细菌线虫数量;NFu为食真菌线虫数量[10]。

1.5 数据分析

数据分析采用SPSS 软件(16.0版, SPSS Inc.)。采样双因子方差分析(Two-way ANOVA)不同处理与采样时期间线虫数量以及多样性指数差异,处理组间差异显著性采用Duncan检验(P<0.05)。

2 结果与分析

2.1 线虫科属及营养类群

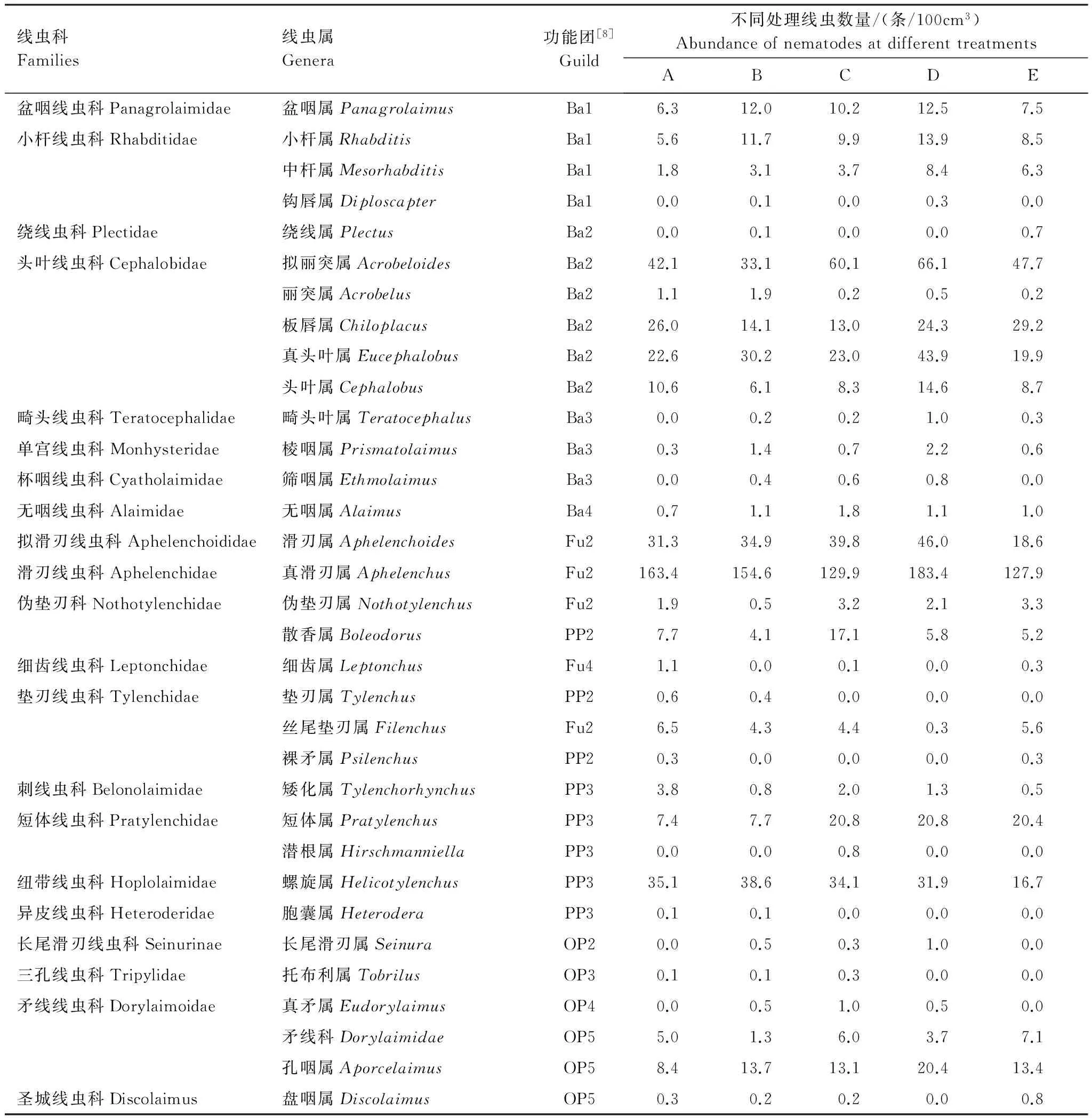

在所采集的45个土壤样品中,土壤线虫分属21科33属 (表1),其中食细菌类15属、食真菌类5属、植物寄生类8属和杂食捕食类5属。各处理线虫属数:处理B(30属)>处理C(28属)>处理A(26属)>处理D和处理E(25属)。在所有处理中,优势类群为拟丽突属Acrobeloides和真滑刃属Aphelenchus,分别占总数的12.3%和37.4% (表1)。常见类群有13属,占总数的47.9%,而稀有类群19属,占总数的2.39%。潜根属Hirschmanniella仅出现在处理C中。垫刃属Tylenchus和胞囊属Heterodera仅在处理A和处理B中出现。按照线虫功能类群,食真菌线虫所占比例最大,为47.5%,其次为食细菌线虫,所占比例为33.7%,植食性线虫,占14.0%和捕食杂食性线虫,占线虫总数4.8%。

2.2 土壤线虫群落c-p值变化

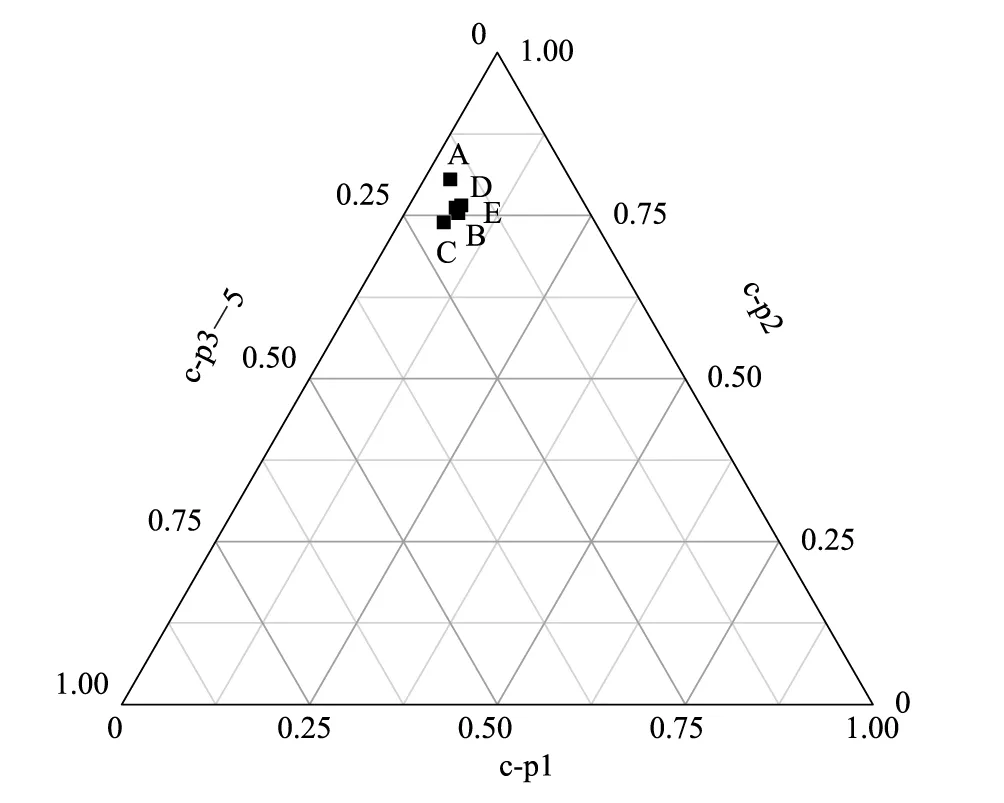

在不同c-p中,以c-p 2所占比例最高,为77.7%,其次是c-p 3,占11.2%,c-p 1占5.88%,c-p 5和c-p 4类群较少,分别占4.86%和0.35%。De Goede等认为线虫主要为c-p 2—4的类群,而c-p1和c-p5相对较少,可以用对c-p 2, c-p 3和c-p 4类群按比例做成三角形图[33]。调查结果表明c-p 1, c-p 2和c-p 3类群较多,而c-p 4和c-p 5类群较少,c-p 1, c-p 2和c-p 3类群所占比例作图(图2),结果表明,几个处理线虫c-p值比例差异不大,基本生活史类型组成相似,说明不同处理类型在生活史组成没有差异。

2.3 不同处理线虫总量以及各营养类型线虫数量比较

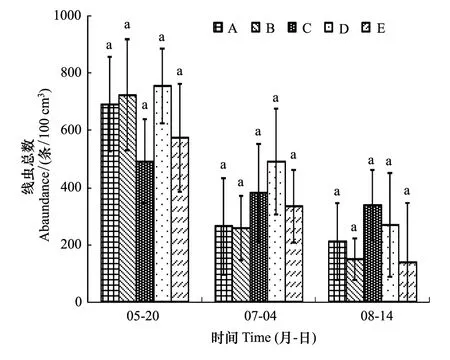

方差分析结果表明,不同处理间土壤线虫总量差异不显著,但不同取样时间线虫总数差异显著(表2),实验开始时数量最多,随后在花期和收获期线虫总数减少(图3)。取样时间与处理间不存在相互作用(表2)。不同营养类型的线虫数量在不同采样时期间有显著差异,但处理与时间之间的交互作用不显著(表2)。

表1 不同处理线虫科属丰富度与功能类群

试验开始时,处理D线虫总数为(756±131)条/100 cm3,而处理C线虫数量最少,为(493±147)条/100 cm3。但到花期7月4日,各处理线虫总数有所下降,但仍以处理D线虫数量最多,但处理间差异缩小。到成熟期,线虫总数进一步减少,处理C线虫总数最多,为(339±123)条/100 cm3,处理E线虫最少,仅(141±205)条/100 cm3。多重比较表明,处理间均无显著差异(图3)。

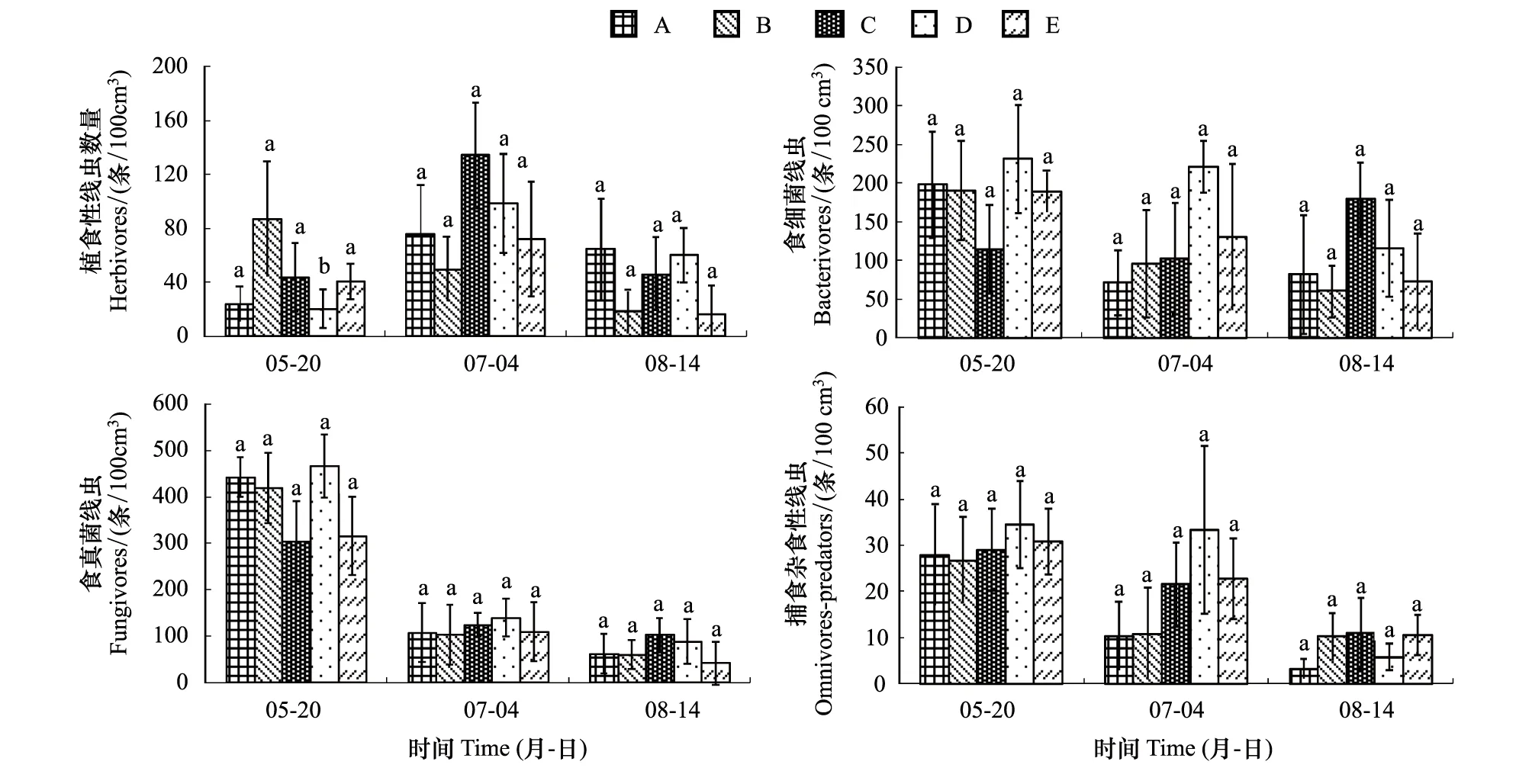

对不同营养类型的线虫数量进行了进一步的比较,植食性线虫在5月20日差异显著(P<0.05,图4 I),处理B数量最高,达(87±37)条/100 cm3,而处理D植食性线虫数量最少,仅(20±14)条/100 cm3。其他时间段不同处理间差异均不显著(P>0.05,图4)。

图2 不同处理线虫c-p值相对丰富度 Fig.2 Relative abundances of nematode taxa classified as c-p 1, c-p 2 and c-p 3—5数据点代表5个不同处理(A、B、C、D、E)平均值

图3 不同处理线虫总量 Fig.3 The total number of nematodes at different treatments图中数据为平均值±标准误,小写字母相同表示组间无显著性差异,字母不同表示有显著性差异,α=0.05

方差分析结果表明,食细菌线虫、食真菌线虫与捕食杂食性线虫在不同处理间均无显著差异(P>0.05)(图4)。

图4 不同处理线虫各营养类型数量比较Fig.4 The number of four feeding types of nematode against different treatments at three sampling times字母相同表示组间无显著性差异,字母不同表示有显著性差异,α=0.05

2.4 不同处理线虫群落结构比较

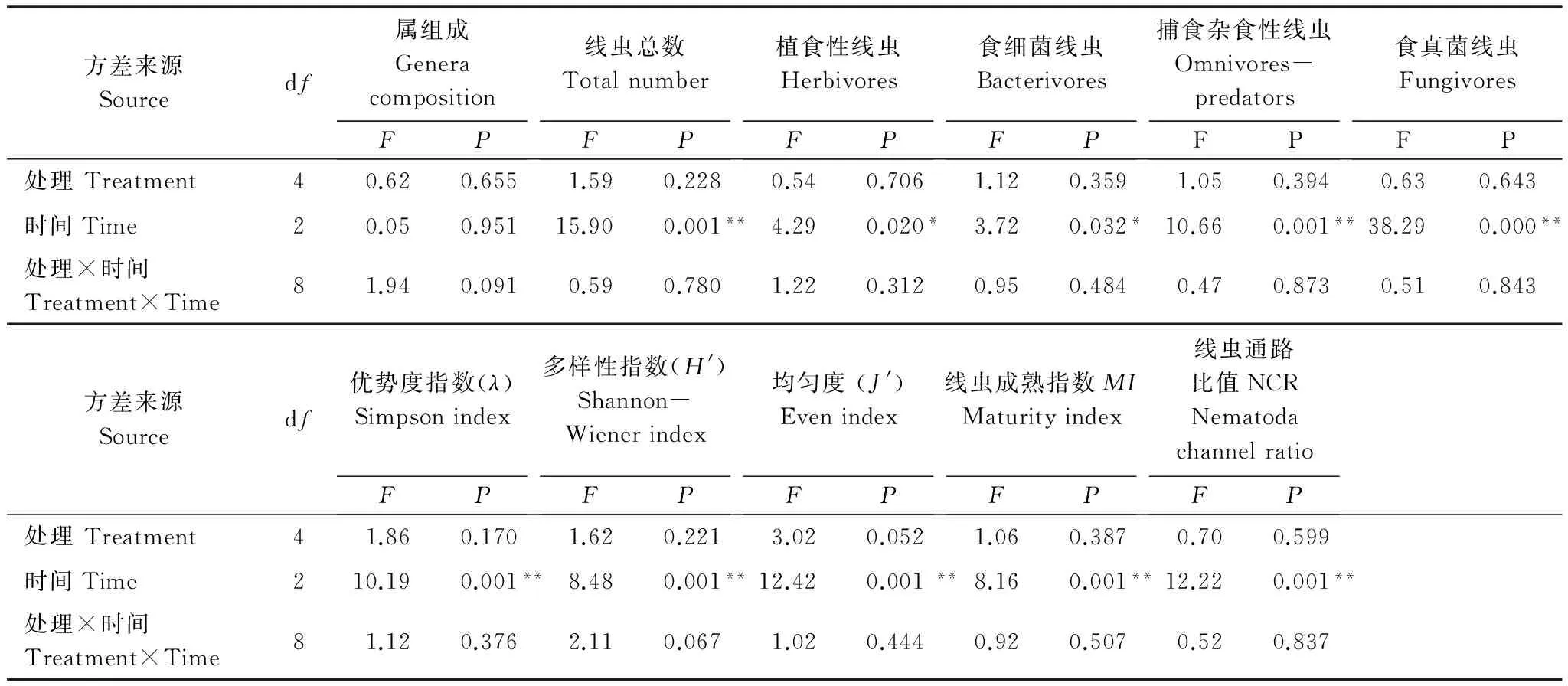

方差分析结果表明,各处理间多样性、优势度、均匀度、成熟度和线虫通路比值(NCR)差异不显著,不同采样时期间差异显著,但处理与时间不存在交互作用(表2)。

表2 不同处理线虫数量组成及群落结构方差分析结果

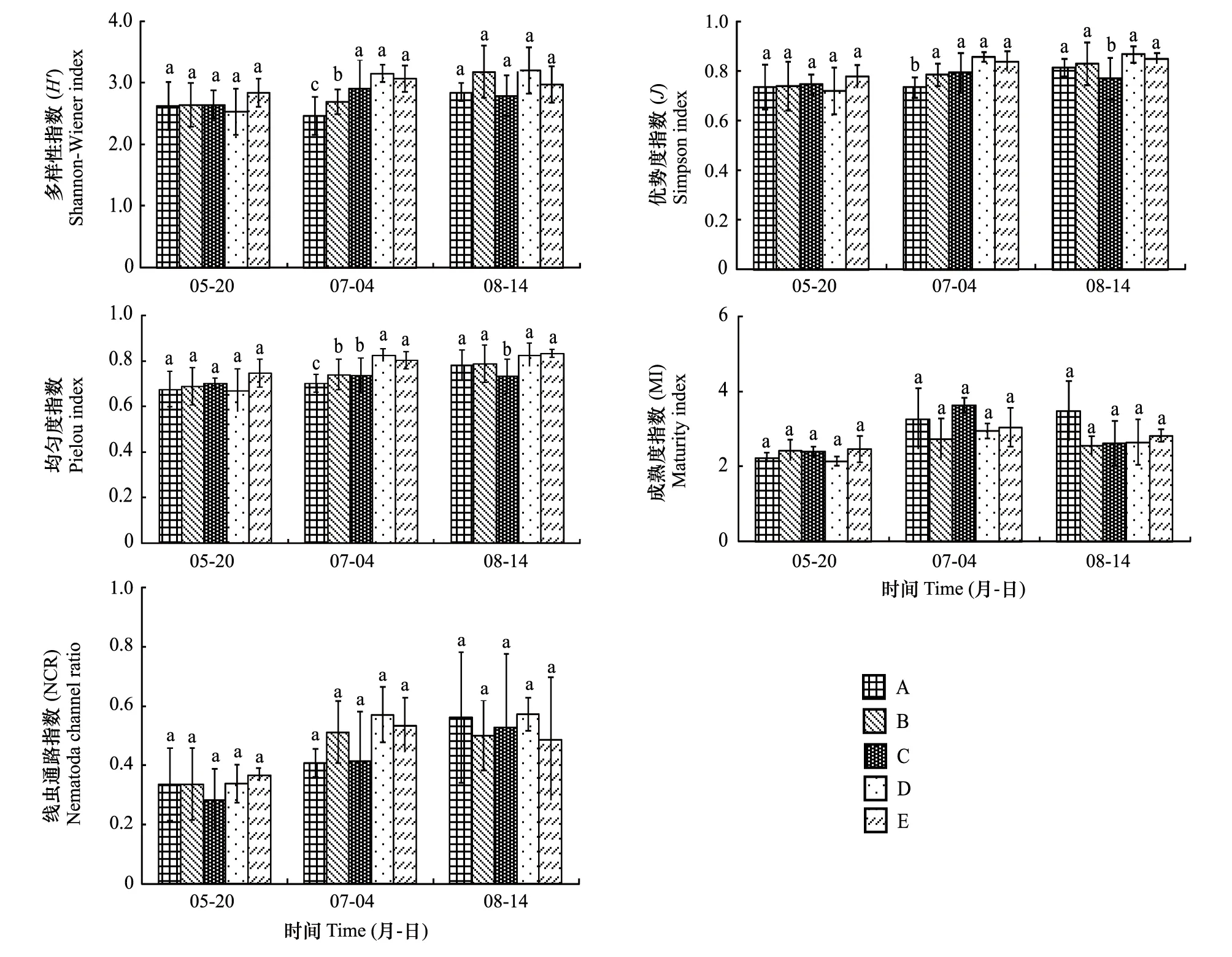

对不同处理线虫数量群落多样性分析(图5),线虫群落Shannon-Wiener多样性指数(H′)、Simpson优势度指数(λ)和均匀度指数(J′)在5月20日处理间无显著差异(图4)。到7月4日,指数间均出现差异,处理D有更高的多样性指数、优势度和均匀度,而处理A多样性、优势度和均匀度均最低,且与处理D存在显著差异(P<0.05)(图5)。到油菜成熟期,处理间多样性差异不显著。但是各处理间优势度与均匀度仍然存在显著差异,处理D优势度与均匀度最高,处理C的优势度与均匀度最低。

各处理线虫成熟度指数(MI)在2.15—3.63之间,NCR(图5)在0.28—0.57之间,在3个取样时间成熟度指数和NCR差异均不显著(P>0.05)。但方差分析结果表明,不同取样时间差异极显著(P<0.01),不同时间与处理间对线虫MI和NCR指数均不存在相互作用(P>0.05)。

图5 不同处理土壤线虫群落多样性分析Fig.5 The diversity of soil nematode communities at different treatments

3 讨论

抗虫转Bt基因作物种植能控制靶标害虫并减少杀虫剂的使用[34-35],减少杀虫剂进入土壤环境,从而减少对土壤生物的环境压力。转基因植物的毒蛋白能通过植物残体和根基分泌物等土壤环境[36-37]。混作常用于提高作物产量,也是常见的控制害虫的耕作模式,混作可以提高作物光能和土地的利用率,增加田间生物多样性。

利用转基因油菜与野芥菜混作,鉴定出土壤线虫33属,线虫总数范围为在141.5—756.0条/100 cm3。线虫总数以及不同营养类型线虫数量均无显著差异。虽然在5月20日处理B(转基因油菜∶野芥菜25∶75)植食性线虫数量显著高于处理D(75∶25)。但本次采样为作物移栽时土壤本底的差异,而本次采样其他处理间不存在显著差异。在随后的2次采样中,不同处理间不存在差异。本文结果说明转基因油菜、野芥菜以及两种作物混作,土壤线虫数量不存在显著差异,说明混作以及单作不影响土壤线虫的数量。其结果与Li和Liu等结论一致,认为长期种植转基因棉花对土壤线虫总数影响很小[38]。Höss等也认为表达Cry1Ab和Cry3Bb1蛋白的Bt玉米对土壤线虫多样性无显著影响[20]。Griffiths等调查欧洲3个研究区表达CryIAb蛋白的转基因玉米(ZeamaysL.)土壤线虫,认为对线虫的动态变化在正常农业变化范围内[39]。Al-Deeb等也证明转Bt基因玉米与非转基因玉米土壤中的线虫数量相当[40]。这些结果均表明,大田种植的不同转Bt作物,对土壤线虫数量影响均不显著。

研究表明转基因油菜单作以及与野芥菜混作不改变线虫生活史组成和群落组成。不同比例转基因油菜与野芥菜混作以及单作处理,土壤线虫中优势类群均为拟丽突属Acrobeloides和真滑刃属Aphelenchus,土壤线虫群落组成变化较小;且5个处理线虫c-p值组成一致(图1),聚成一类,转基因油菜单作以及与野芥菜混作后,各处理间线虫群落组成不存在明显差异。结果与Yang等结论一致[12],认为转基因棉花的种植不影响土壤线虫群落组成。但不同作物农田土壤线虫优势类群不一样,Yang等棉田中优势类群为拟丽突属Acrobeloides、真头叶属Eucephalobus, 和真滑刃属Aphelenchus。但Li和Liu调查多年转基因棉种植田间主要类群为螺旋属Helicotylenchus、丝尾垫刃属Filenchus和拟丽突属Acrobeloides,不同作物种植类型和不同种植年限,可能导致线虫优势类群不同。

转基因油菜与野芥菜混作不改变土壤线虫多样性。虽然在7月4日,线虫多样性指数、优势度指数和均匀度指数在100%野芥菜处理A和转基因油菜与野芥菜75∶25处理D间存在显著差异,8月14日,处理D的优势度与均匀度明显高于处理C,但在整体方差分析结果表明各指数在处理间无线虫差异(表3)。在成熟度MI指数与线虫通路指数NCR指数也有着相似的变化规律。其结果与转基因棉田土壤线虫一致[12, 38]。转基因油菜与野芥菜混作不影响土壤线虫群落结构。时培建等认为作物物种丰富度显著性影响害虫物种丰富度,混栽田中节肢动物群落稳定性高于单一种植田中节肢动物群落稳定性[41]。但本实验表明单作以及混作处理后,植食性土壤线虫数量没有发生显著变化,不同营养类型线虫数量不存在显著差异,转基因油菜与野芥菜混作与单作相比并没有增加土壤线虫多样性。

本文实验结果表明,转基因油菜与野芥菜按不同比例混作,土壤线虫优势类群相同,线虫总数与不同营养类型线虫数量不存在显著差异,线虫生活史策略(c-p值)组成相似。线虫群落参数亦不存在显著差异,转基因油菜与野芥菜混作短期内没有使土壤线虫群落结构发生明显改变。

[1] James C. Global Status of Commercialized Biotech/GM Crops: 2012. The International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications Briefs No. 44. Ithaca, NY, 2012: 1-18.

[2] Lu Y H, Wu K M, Jiang Y Y, Xia B, Li P, Feng H Q, Wyckhuys K A G, Guo Y Y. Mirid bug outbreaks in multiple crops correlated with wide-scale adoption of Bt cotton in China. Science, 2010, 328(5982): 1151-1154.

[3] Ramachandran S, Buntin G D, All J N, Raymer P L, Stewart C N. Intraspecific competition of an insect-resistant transgenic canola in seed mixtures. Agronomy Journal, 2000, 92(2): 368-374.

[4] Wu K, Feng H, Guo Y. Evaluation of maize as a refuge for management of resistance to Bt cotton byHelicoverpaarmigera(Hübner) in the Yellow River cotton-farming region of China. Crop Protection, 2004, 23(6): 523-530.

[5] Hokkanen H M T, Wearing C H. Assessing the risk of pest resistance evolution toBacillusthuringiensisengineered into crop plants: a case study of oilseed rape. Field Crops Research, 1996, 45(1/3): 171-179.

[6] Yang B, Ge F, Ouyang F, Parajulee M. Intra-species mixture alters pest and disease severity in cotton. Environmental Entomology, 2012, 41(4): 1029-1036.

[7] Yang B, Parajulee M, Ouyang F, Wu G, Ge F. Intraspecies mixture exerted contrasting effects on nontarget arthropods ofBacillusthuringiensiscotton in northern China. Agricultural and Forest Entomology, 2014, 16(1): 24-32.

[8] Yeates G W, Bongers T, De Goede R G M, Freckman D M, Georgieva S S. Feeding habits in soil nematode families and genera -an outline for soil ecologists. Journal of Nematology, 1993, 25(3): 315-331.

[9] Bongers T. The maturity index: an ecological measure of environmental disturbance based on nematode species composition. Oecologia, 1990, 83(1): 14-19.

[10] Yeates G W. Nematodes as soil indicators: functional and biodiversity aspects. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 2003, 37(4): 199-210.

[11] 肖能文, 谢德燕, 王学霞, 闫春红, 胡理乐, 李俊生. 大庆油田石油开采对土壤线虫群落的影响. 生态学报, 2011, 31(13): 3736-3744.

[12] Yang B, Chen H, Liu X H, Ge F, Chen Q Y. Bt cotton planting does not affect the community characteristics of rhizosphere soil nematodes. Applied Soil Ecology, 2014, 73: 156-164.

[13] Stewart Jr C N, Adang M J, All J N, Raymer P L, Ramachandran S, Parrott W A. Insect control and dosage effects in transgenic canola containing a syntheticBacillusthuringiensiscryIAc gene. Plant Physiology, 1996, 112(1): 115-120.

[14] Stewart C N, All J N, Raymer P L, Ramachandran S. Increased fitness of transgenic insecticidal rapeseed under insect selection pressure. Molecular Ecology, 1997, 6(8): 773-779.

[15] Burgio G, Lanzoni A, Accinelli G, Dinelli G, Bonetti A, Marotti I, Ramilli F. Evaluation of Bt-toxin uptake by the non-target herbivore,Myzuspersicae(Hemiptera: Aphididae), feeding on transgenic oilseed rape. Bulletin of Entomological Research, 2007, 97(2): 211-215.

[16] Pierre J, Marsault D, Genecque E, Renard M, Champolivier J, Pham-Delègue M H. Effects of herbicide-tolerant transgenic oilseed rape genotypes on honey bees and other pollinating insects under field condtions. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 2003, 108(3): 159-168.

[17] Howald R, Zwahlen C, Nentwig W. Evaluation of Bt oilseed rape on the non-target herbivoreAthaliarosae. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 2003, 106(2): 87-93.

[18] Saxena D, Stotzky G.Bacillusthuringiensis(Bt) toxin released from root exudates and biomass of Bt corn has no apparent effect on earthworms, nematodes, protozoa, bacteria, and fungi in soil. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2001, 33(9): 1225-1230.

[19] Zwahlen C, Hilbeck A, Howald R, Nentwig W. Effects of transgenic Bt corn litter on the earthwormLumbricusterrestris. Molecular Ecology, 2003, 12(4): 1077-1086.

[20] Höss S, Nguyen H T, Menzel R, Pagel-Wieder S, Miethling-Graf R, Tebbe C C, Jehle J A, Traunspurger W. Assessing the risk posed to free-living soil nematodes by a genetically modified maize expressing the insecticidal Cry3Bb1 protein. Science of the Total Environment, 2011, 409(13): 2674-2684.

[21] Wei J Z, Hale K, Carta L, Platzer E, Wong C, Fang S C, Aroian R V.Bacillusthuringiensiscrystal proteins that target nematodes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2003, 100(5): 2760-2765.

[22] Liu Y B, Tang Z X, Darmency H, Stewart C N Jr, Di K, Wei W, Ma K P. The effects of seed size on hybrids formed between oilseed rape (BrassicaNapus) and wild brown mustard (B.Juncea). PLoS ONE, 2012, 7(6): e39705.

[23] Halfhill M D, Richards H A, Mabon S A, Stewart C N. Expression of GFP and Bt transgenes inBrassicanapusand hybridization withBrassicarapa. Theoretical and Applied Genetics, 2001, 103(5): 659-667.

[24] Ingham R E. Nematodes. Methods of Soil Analysis. Part 2. Microbiological and Biochemical Properties//Weaver R W, Angle S, Bottomley P, Bezdicek D, Smith S, Tabatabai A, Wollum A, eds. Society of America Book Series: Madison, WI.1994, 459-490.

[25] Goodey T. Soil and Freshwater Nematodes. New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc., 1963.

[26] 尹文英. 中国土壤动物检索图鉴.北京: 科学出版社, 1998.

[27] 刘维志. 植物线虫志.北京: 中国农业出版社, 2004.

[28] Neher D A. Role of nematodes in soil health and their use as indicators. Journal of Nematology, 2001, 33(4): 161-168.

[29] Shannon C E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell System Technical Journal, 1948, 27(3):379-423.

[30] Pielou E C. Mathematical Ecology. New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc., 1977.

[31] Simpson E H. Measurement of diversity. Nature, 1949, 163(4148): 688-688.

[32] Neher D A, Peck S L, Rawlings J O, Campbell C L. Measures of nematode community structure and sources of variability among and within agricultural fields. Plant and Soil, 1995, 170(1): 167-181.

[33] De Goede R G M, Bongers T, Ettema C H. Graphical presentation and interpretation of nematode community structure: c-p triangles. Medical Faculty Landbouww University of Gent, 1993, 58(2b): 743-750.

[34] Lu Y H, Wu K G, Jiang Y Y, Guo Y, Desneux N. Widespread adoption of Bt cotton and insecticide decrease promotes biocontrol services. Nature, 2012, 487(7407): 362-365.

[35] Cattaneo M G, Yafuso C, Schmidt C, Huang C Y, Rahman M, Olson C, Ellers-Kirk C, Orr B J, Marsh S E, Antilla L, Dutilleul P, Carrière Y. Farm-scale evaluation of the impacts of transgenic cotton on biodiversity, pesticide use, and yield. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2006, 103(20): 7571-7576.

[36] Wang Y M, Hu H W, Huang J C, Li J H, Liu B, Zhang G. Determination of the movement and persistence of Cry1Ab/1Ac protein released from Bt transgenic rice under field and hydroponic conditions. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2013, 58: 107-114.

[37] Saxena D, Stotzky G. Insecticidal toxin fromBacillusthuringiensisis released from roots of transgenic Bt corn in vitro and in situ. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2000, 33(1): 35-39.

[38] Li X G, Liu B. A 2-year field study shows little evidence that the long-term planting of transgenic insect-resistant cotton affects the community structure of soil nematodes. PLoS ONE, 2013, 8(4): e61670.

[39] Griffiths B S, Caul S, Thompson J, Birch A N E, Scrimgeour C, Andersen M N, Cortet J, Messéan A, Sausse C, Lacroix B, Krogh P H. A comparison of soil microbial community structure, protozoa and nematodes in field plots of conventional and genetically modified maize expressing theBacillusthuringiensis CryIAb toxin. Plant and Soil, 2005, 275(1/2): 135-146.

[40] Al-Deeb M A, Wilde G E, Blair J M, Todd T C. Effect of Bt corn for corn rootworm control on nontarget soil microarthropods and nematodes. Environmental Entomology, 2003, 32(4): 859-865.

[41] 时培建, 惠苍, 门兴元, 赵紫华, 欧阳芳, 戈峰, 金显仕, 曹海锋, Larry L B. 作物多样性对害虫及其天敌多样性的级联效应. 中国科学: 生命科学, 2014, 44(1): 75-84.

Effect of interspecific mixed cropping between transgenic oilseed rape and wild mustard on soil nematode communities

XIAO Nengwen1, LIU Yongbo1, CHEN Qunying2, FU Mengdi1, YE Yao1, LI Junsheng1,*

1StateKeyLaboratoryofEnvironmentalCriteriaandRiskAssessment,ChineseResearchAcademyofEnvironmentalSciences,Beijing100012,China2StateKeyLaboratoryofIntegratedManagementofPestInsectsandRodents,InstituteofZoology,ChineseAcademyofSciences,Beijing100080,China

As genetically modified (GM) crops are cultivated worldwide, the effects of GM crops on non-target organisms are of concern. Interspecific mixed cropping between transgenic and non-transgenic crops is generally regarded as a strategy against insects to minimize the development of resistance to otherwise insect-resistant transgenic crops. The toxin fromBacillusthuringiensis(Bt) is introduced into the soil primarily through root exudates and by the incorporation of plant residues after harvest, with probable help from pollen. Such incorporation of the toxin poses potential risks to soil organisms, including microbes, nematodes, collembolans, and other invertebrates. However, its effects on non-target soil organisms have rarely been assessed. We evaluated the effect on soil nematodes of mixed cropping with transgenic canolaBrassicanapusL. expressing Bt and wild brown mustardB.juncea. The abundance and genera composition of soil nematodes in the flowering and fruiting period of canola were investigated in five mixed proportions of transgenic canola and wild brown mustard: 0∶100 (A), 25∶75 (B), 50∶50 (C), 75∶25 (D), and 100∶0 (E). The results showed the following order of genera composition with each treatment: B (30 genera) > C (28 genera) > A (26 genera) > D and E (25 genera). The dominant nematode genera wereAcrobeloidesandAphelenchus, accounting for 37.4% and 12.3% of total abundance, respectively. The common and rare groups belonging to 13 and 19 genera accounted for 47.9% and 2.39% of the total, respectively.Hirschmanniellaappeared only in treatment C.TylenchusandHeteroderaappeared only in treatments A and B. Depending on the trophic structure based on the functional group, fungivorous nematodes formed the largest proportion at 47.5%, followed by bacterivorous, herbivorous, and omnivorous-predatory nematodes at 33.7%, 14%, and 4.8% of the total, respectively. The colonizer-persister (c-p) values of nematodes had the same composition among the five treatments. Further, similar life histories were noted following the treatments. The total number of nematodes was in the range of 141.5—756.0/100 cm3. The total abundance and number of four feeding types of nematodes were not significantly different among treatments. The generic composition and community parameters of nematodes did not differ significantly among the five treatments. The Shannon-Wiener diversity index (H′), Simpson index (λ), and evenness index (J′) of soil nematode communities showed no significant differences among treatments on May 20. However, treatment D showed a high diversity index, dominance, and evenness index on July 4, and the highest Simpson index and evenness index on August 22. Nematode maturity index (MI) was in the range of 2.15—3.63; nematode channel ratio (NCR) was 0.28—0.57 for the three sampling times in each treatment. Thus, theH′,λ,J′,MI, and NCR of the nematodes varied with time. These results suggest that sole cropping or mixed cropping of transgenic canola with wild brown mustard had no short-term impact on the soil nematode community.

transgenic canola; wild brown mustard; interspecific mixed cropping; soil nematodes; community structure

中央级公益性科研院所基本科研业务专项(2013-YSKY-16); 国家自然科学基金青年项目(31200288)

2014-01-21;

日期:2014-11-19

10.5846/stxb201401210157

*通讯作者Corresponding author.E-mail: lijsh@craes.org.cn

肖能文, 刘勇波, 陈群英, 付梦娣, 叶瑶, 李俊生.转基因油菜与野芥菜混作对土壤线虫群落的影响.生态学报,2015,35(18):6189-6198.

Xiao N W, Liu Y B, Chen Q Y, Fu M D, Ye Y, Li J S.Effect of interspecific mixed cropping between transgenic oilseed rape and wild mustard on soil nematode communities.Acta Ecologica Sinica,2015,35(18):6189-6198.