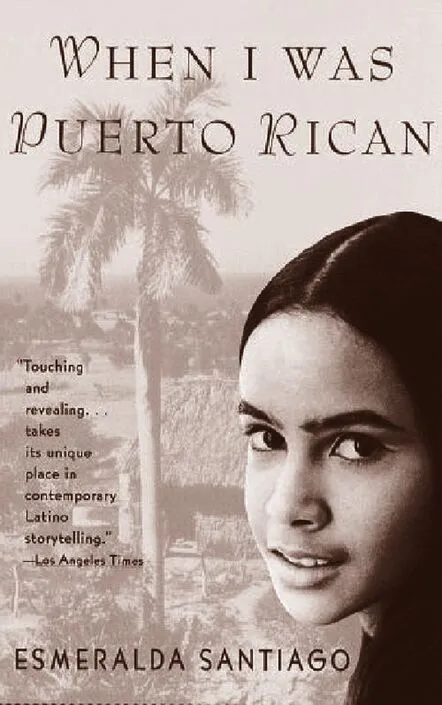

When I Was Puerto Rican

By Esmeralda Santiago

My parents probably argued before Héctor was born. Mami was not one to hold her tongue when she was treated unfairly. And while Papi was easygoing and cheerful most of the time,his voice had been known to rise every so often, sending my sisters and me scurrying(急跑)for cover(躲避)behind the annatto(胭脂树)bushes or under the bed.But the year that Héctor was born their fights grew more frequent and sputtered(喷溅)into our lives like water on a hot skillet(平底锅).

“Where’s my yellow shirt?” Papi asked one Sunday morning as he rummaged(到处翻寻)through the clothes rack he’d put up near the bed.

“I haven’t ironed it yet.” Mami rocked on her chair,nursing Héctor. “Where are you going?”

“Into town for some things.” Papi kept his back to her as he tucked a blue shirt into his pants.

“What things?”

“Plans for the new job.” He shook cologne(古龙香水)into his hands and slapped it around his face and behind his ears.

“When will you be back?”

Papi sighed loud and deep. “Monín, don’t start with me.”

“Start what? I asked you a simple question.” She leveled her eyes(眼睛平视)and set her lips into a straight line.

“I don’t know when I’ll be back. I’ll stop in to see Mamá,so I’ll probably have dinner there.”

“Fine.” She got up from her chair and walked out of house, Héctor attached to her breast.

Papi brushed his leather shoes and stuffed them inside a plaid(格子的)zippered(拉链式的)duffel bag(圆筒状行李袋). He put on canvas(帆布)loafers(休闲鞋) that had once been white but had yellowed with the dirt of the road.He unhooked his straw hat(草帽)from nail by the door and left without kissing us good-bye.

I went looking for Mami behind the house. She sat on a stump(树桩)under the breadfruit tree, her back to me.Her shoulders bobbed up and down, and she whimpered(啜泣)quietly, every so often wiping her face with the edge of Hector’s baby blanket. I walked to her, tears stinging the rims of my eyes. She turned around with an angry face.

“Leave me alone! Get away from me.”

I froze. She seemed so far away, yet I sensed the heat from her body, smelled the rosemary(迷迭香)oil she rubbed on her hair. I didn’t want to leave her but was afraid to come closer, so I leaned against a mango tree and stared at my toes against the moriviví(含羞草)weed.Every so often she looked over her should, and I turned my eyes to the front yard, where Delsa and Norma chased one another, a cloud of dust painting their legs up to their droopy(下垂的)panties(女式短裤).

波多黎各作家埃斯梅拉达·圣地亚哥是拉美作家群中一颗闪亮的明珠。她创作于1994年的When I was Puerto Rican(《当我还是个波多黎各人》)是一部个人回忆录,埃斯梅拉达以抑扬顿挫的文字以及充满画面感的笔触,讲述了她在波多黎各童年生活的贫困以及12岁随母亲移居美国布鲁克林后的彷徨和抗争的生活经历。作者独特的写作风格赋予作品强大的感染力,一旦开卷,难以释手。本期选登的这一片段描写了作者父母之间的矛盾和争吵。已经生育了6个孩子的母亲又怀孕了,而父亲却又有了外遇。

“Here,” Mami stood over me, holding a drowsy(昏昏欲睡的)Héctor, “put him to bed while I heat you kids some lunch.”

Her face was swollen(肿胀的), her lashes(睫毛)clumped(凝结)into spikes. I slung Hector over my shoulder, his baby body yielding onto mine. Mami raked her fingers through my hair with a sad smile then walked away, the hem of her dress swinging in rhythm to her rounded hips.

Papi didn’t come home for days. Then one night he appeared, kissed us hello, put on his work clothes, and began hammering on the walls. When he’d finished, he washed his hands and face at the barrel near the back door, sat at the table, and waited for Mami to serve him supper. She banged a plateful of rice and beans in front of him, a fork, a glass of water. He didn’t look at her; she didn’t look at him. While he ate, Mami told us to get ready for bed, and Delsa, Norma, and I scrambled into our hammocks(吊床). She nursed Hector and put him to sleep. Papi’s newspaper rustled, but I didn’t dared poke my head out.

I drifted into(不知不觉陷入)a dream in which I climbed a tall tree whose lower branches disappeared the moment I scaled the higher ones. The ground moved farther and farther away, and the top of the tree stretched into the clouds, which were pink. I woke up sweating, my arms stretched over my head and gripping the rope of my hammock. The quinqué’s(煤油灯) flame threw orange shadows onto the curtain stretched across the room.

Mami and Papi lay in bed talking.

“You haven’t given me money for this week’s groceries.”

The bed creaked as Papi turned away from Mami. “I had to buy materials. And one of the men that works with me had an emergency. I gave him an advance(预付款).”

“An advance?!”

Mami had a way of making a statement with a question.From my hammock on the other side of the curtain I envisioned(想象) her face: eyes round, pupils large, her eyebrows arched to the hairline. Her lips would be half open, as if she’d been interrupted in the middle of an important word. When I saw this expression on her face and heard that tone of voice, I knew that whatever I’d said was so far from the truth, there was no use trying to argue with her. Even if what I said was true, that tone of voice told me she didn’t believe me, and I’d better come up with a more convincing story. Papi either couldn’t think of another story or was too tired to try, because he didn’t say anything. I could have told him that was a mistake.

“You gave him an advance?! An advance??”

Her voice had gone from its “I don’t believe you” tone to its“How dare you lie to me” sound.

“Monín,” the bed creaked as Papi turned to her. “Can we talked about this in the morning? I need to sleep.”

His voice was calm. When Mami was angry, she argued in a loud voice that reached higher pitches the more nervous she became. When Papi argued, he put all his energy into holding himself erect, maintaining a steady calm that was chilling to us children but had the opposite effect on Mami.

“No, we can’t talk about this in the morning. You leave before the sun comes up, and you don’t show up until all hours,your clothes stinking like that puta (妓女).

……

Another time they were arguing, and I heard Mami accuse Papi, as she often did, of seeing another woman behind her back when he said he was going to see Abuela(外婆).

“For God’s sake, Monn. You know I have no interest in Provi. But how can you object to my wanting to see Margie?”Papi asked.

“I know it’s not Margie you want to see. It’s her mother.”

“Monín, please. That’s been over for years.”

And on they went, Mami accusing Papi and Papi defending himself. When they’d reached a truce(停止争吵)and I had a few moments alone with Papi, I asked him, “Who’s Margie?”

He looked at me with a scared expression.

“She’s my daughter,” he said after a pause. My heart shrank. Having to share my father with Delsa, Norma,and Hector was bad enough. I waited for him to say more,but he didn’t. He sat on a stump and stared at his hands,calloused(长茧的)where the hammer and saw handles rubbed against his skin. He looked so sad, it made me want to cry. I sat next to him.

“Where does she live?”

He seemed to have just remembered I was there. “In Santurce.”

“How old is she?”

“Just a year older than you.”

An older sister! I’d wondered what it would be like not to be the oldest, the one who set an example for the little ones.

“How come she’s never been to see us?”

“Her mother and your mother don’t get along.”

That much I figured out. “You can just bring her sometime. Her mother doesn’t have to come.”

Papi sighed then chuckled. “That’s a good idea,” he said and stood up. “I have to get some work done. Can you help me mix concrete?”

I poured the water for him while he stirred cement and sand together. I asked him many questions about Margie,and he answered them in short phrases that didn’t tell me much. If we were talking about her and Mami came near,he’d put his hand to his mouth so I’d quiet, and we’d work in silence until she was out of earshot .

At night I tried to imagine what Margie looked like. I envisioned her skin the same carob color as my father’s, her eyes as black and her lips as full as his. Her hair kinky(卷曲的)like his, not lanky(细长的)like mine. I imagined her voice to be musical, lilting(抑扬顿挫的), the way his was when he read poetry to us.

What times we could have it if we were together! She’d be someone I could have fun with, not be responsible for. She’d be able to keep up with me when we ran across the field. She’d climb a tree without being helped. We could play hide-and-seek in the jungled back yard. We’d climb the fence behind the house and steal into Lalao’s grapefruit grove to fill our faces with the bittersweet pulp while juice dribbled(滴下)down our chins and our fingers got sticky. I swayed in my hammock dreaming about Margie, determined to talk my mother into asking Papi to bring her to live with us.

……

The next day I stood on a stool while Mami pinned the hem on my school uniform.

“Mami, why don’t you like Margie’s mother?”

“Who?”

“Provi, my sister Margie’s mother.”

“Negi, I never want to hear you mention that woman’s name again, you hear me?”

“But Mami…”“I mean it.”

“But Mami…”

“Stand still or I’m going to have an accident with these pins.”

I stood still as a statue while she finished.

……

Men, I was learning, were sinvergüenzas(不知羞耻的), which meant they had no shame and indulged(沉溺)in behavior that never failed to surprise women but caused them much suffering. Chief among the sins of men was the other woman, who was always a puta,a whore. My image of these women was fuzzy, since there were none in Macún, where all the females were wives or young girls who would one day be wives.Putas, I guessed, lived in luxury in the city on the money that sinvergüenza husbands did not bring home to their long-suffering wives and barefoot children.Putas wore lots of perfume, jewelry, dresses cutlow to show off their breasts, high heels to pump up their calves(小腿), and hair spray(发胶). All this was paid for with money that should have gone into repairing the roof or replacing the dry palm fronds(叶子)enclosing the latrine(坑厕)with corrugated(波纹的)steel sheets. I wanted to see a puta close up, to understand the power she held over men, to understand the sweet-smelling spell she wove around the husbands, brothers, and sons of the women whose voices cracked with pain, defeat, and simmering(即将爆发的)anger.

作者