Parental perceptions of the effects of exercise on behavior in children and adolescents w ith ADHD

Jennifer I.Gapin,Jennifer L.Etnier

aDepartment of Kinesiology and Health Education,Southern Illinois University at Edwardsville,Edwardsville,IL 62026,USA

bDepartment of Kinesiology,University of North Carolina at Greensboro,Greensboro,NC 27412,USA

Parental perceptions of the effects of exercise on behavior in children and adolescents w ith ADHD

Jennifer I.Gapina,*,Jennifer L.Etnierb

aDepartment of Kinesiology and Health Education,Southern Illinois University at Edwardsville,Edwardsville,IL 62026,USA

bDepartment of Kinesiology,University of North Carolina at Greensboro,Greensboro,NC 27412,USA

Background:Anecdotally,parents often report thatchildren w ith attention deficithyperactivity disorder(ADHD)who engage in regularphysical activity(PA)experience positive behavioralchanges.The purpose of this study was to exam ine this anecdotal relationship to provide prelim inary evidence relevant to the potential benefi ts of PA on ADHD symptoms.

Methods:Parents(n=68)of children diagnosed w ith ADHD completed an Internet survey assessing perceptions of how PA influences their child’s symptoms.

Results:A significantly greater percentage of parents reported that regular PA positively impacted symptoms.However,there were no uniform effects for all types of ADHD symptoms.The results indicate that there may be more positive benefi ts for symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity than for those of impulsivity.

Conclusion:This is the fi rst study to empirically document parents’perceptions of how PA influences ADHD and suggests that PA can be a viable strategy for reducing symptoms.PA may have greater benefi ts for specific symptoms of ADHD,providing critical information for developing PA interventions for children and adolescents.

CopyrightⒸ2013,Shanghai University of Sport.Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.A ll rights reserved.

Attention defi cit;Behavior;Pediatrics;Physical activity

1.Introduction

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder(ADHD)is one of the leading childhood psychiatric disorders in America and is a costly major public health problem.ADHD affects approximately 3%—7%of schoolage children1and successful school outcomes for children w ith ADHD depend upon the degree to which treatment components meet the needs of a particular child.ADHD is characterized by age-inappropriate core symptoms of inattention,hyperactivity,and/or impulsivity which occur for at least 6 months in at least two domains of life,beginning prior to the age of 7 years.1These core symptoms persist into adulthood and can cause numerous impairments in a host of life domains.ADHD is most commonly treated through the use of stimulant medications, primarily methylphenidate(e.g.,Ritalin)and amphetam ines (e.g.,Adderall).The second most common form of treatment is the use of behavioral interventions such as parent training and contingency management.Both pharmacological(e.g., stimulant medications)and behavioral interventions are effective in m itigating symptoms of ADHD,2,3however both have their limitations suggesting that research on alternative and/or complementary treatments is necessary.One lim itation is that while both treatment types have proven efficacious intreating the core symptoms of ADHD in the short-term,there are few long-term benefi ts3,4and poor compliance rates.5,6An additional lim itation of pharmacological treatment are side effects such as sleep disturbance,appetite suppression,headaches,and stomachaches,which all can negatively influence health outcomes and academ ic performance.7

Given thatpharmacologicalinterventions are noteffective or viable options for some patients in managing their ADHD symptoms and that currentbehavioral treatments have limitations,the identification ofother formsof treatmentiswarranted. Previous research has identified desirable characteristics of effective treatments which include that the treatmentis socially valid and acceptable,8functionally based,9applied w ith a high degree of treatment integrity,10and has a benign side effect profi le.Physicalactivity(PA)appearsto fi tthese characteristics welland may be an effective adjunctive treatment intervention for ADHD.Anecdotally,parents and teachers often report that children w ith ADHD who are physically active experience positive changes in behavior patterns.However,PA has been relatively unexplored empirically as a behavioral treatment for children w ith ADHD.

The potential of PA as a treatment for ADHD is supported by the fact that PA has been found to positively impactmany of the same neurobiological factors that are implicated in ADHD.An extensive body of evidence com ing from animal models and recent studies w ith humans supports this statement.First,fMRI studies of individuals w ith ADHD show reduced cerebral blood flow and reduced activation in prefrontal and striatal areas of the brain for behavioral control tasks.11,12Animal models show that PA results in increased cerebralblood flow13,14and in human studies participants that are more aerobically fi t show benefi ts in brain activity within regions associated w ith behavioral confl ict and attentional control processes.15Additionally,PA increases the availability of dopam ine and norepinephrine in synaptic clefts of the central nervous system.16,17These neurotransm itters play essential roles in attention,maintaining alertness,increasing focus,and sustaining thought,effort,and motivation.Consequently,albeit indirect,this evidence suggests the possibility that for children w ith ADHD,PA may be beneficial in reducing symptom severity.

Only a few studies have exam ined the impact of PA on ADHD and the focus has been on acute exercise and its effects on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis18or dopam inergic responses.19Only one study has exam ined the impactof PA on behavioral symptoms in children w ith ADHD and results demonstrated that behavior,as measured by parent ratings on the Conners Parent Rating Scale,improved after a 5-week exercise program.20Further,no studies have explored the possible impact of chronic or regular exercise on behavioral symptoms of ADHD.Therefore the purposes of this study were two-fold.The primary purpose was to exam ine the anecdotal relationship between PA and ADHD symptoms to provide prelim inary evidence for the benefi ts of regular PA in reducing ADHD symptoms.The second purpose was to collect qualitative data aboutparents’perceptions of the effects of PA on ADHD symptoms.

2.M aterials and methods

2.1.Participants

Participants were recruited via email and Internetmessage boards affi liated w ith Children and Adults w ith Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder(CHADD)regional chapters in the month of September.The study was also posted on the CHADD website.In order to be included in the study participants had to be parents and/or guardians of a child or adolescentbetween the ages of5—18 who had been diagnosed w ith ADHD by a medical professional.

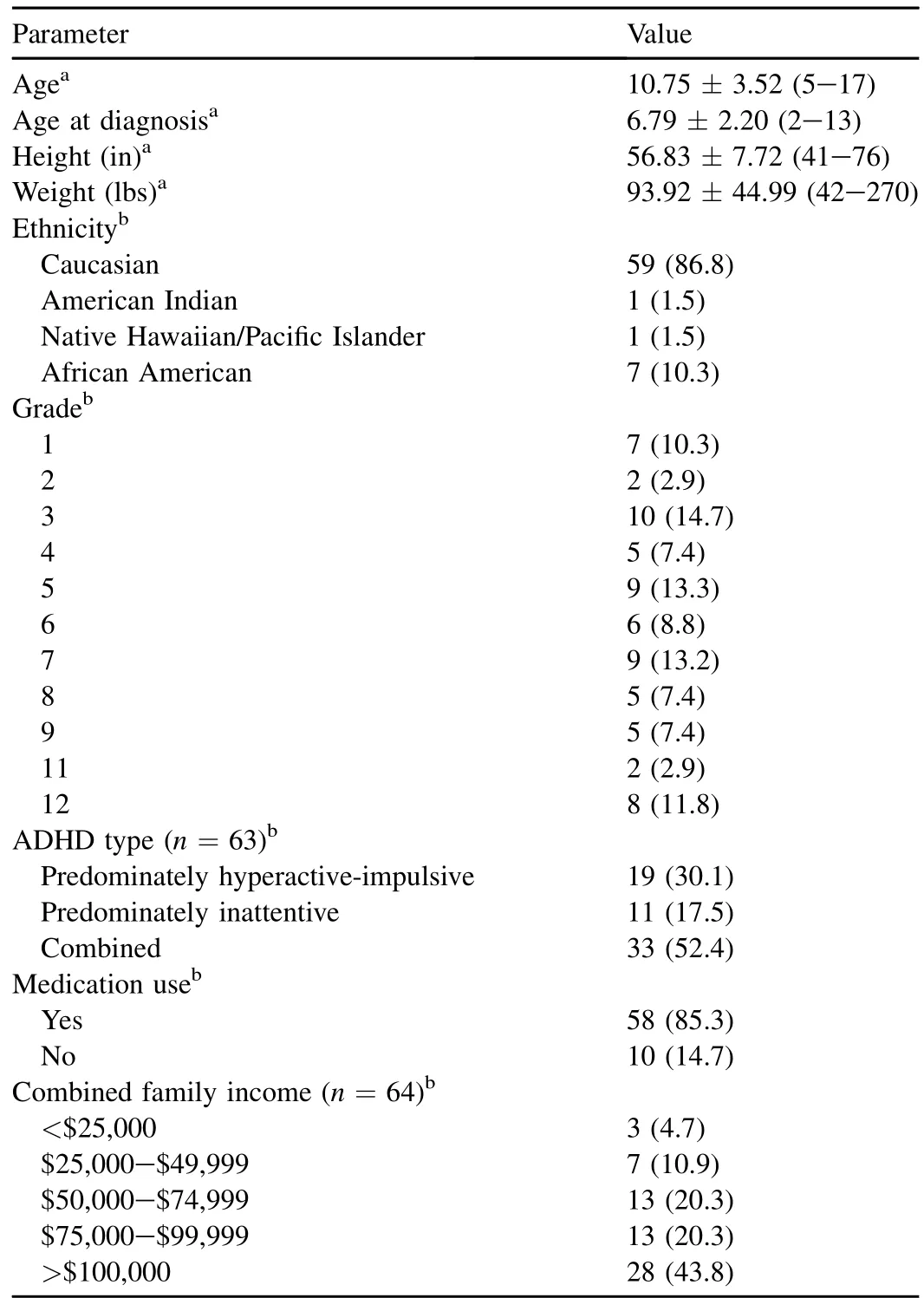

Since this was a pilot exploratory study and we had a lim ited time frame of 1 month to collect data,we aimed to recruit 100 participants.A total of 96 participants completed the survey,however only 68 participants provided complete data and met the requirements of the study.The final sample consisted of 68 parents of children diagnosed w ith ADHD. Descriptive information for the children are summarized in Appendix.Based on parent report,all participants were previously diagnosed w ith ADHD by a medical professional. The majority of the sample(85%)reported using medication to treat ADHD.

2.2.Procedure and measures

This project involved using a web based survey to collect information from parents of children w ith ADHD relative to how PA impacts ADHD symptoms.The Internet survey assessed demographic information,ADHD diagnosis and history,PA participation and questions that obtained the parent(s)perceptions of how PA affects their child’s ADHD symptoms.These questions were generated by the research team to assess perceptions of how PA influences their child’s ADHD symptoms.These were exploratory and used for descriptive purposes.More specifically,parents were asked if when their child was physically active,they noticed a difference in ADHD symptoms broadly;in symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity,or impulsivity specifically;and in academic performance.Ifa difference was reported(participants marked“yes”),then they were asked to indicate how and whether the difference was positive or negative or both positive and negative.For example,to assess symptoms broadly the question stated:“Very broadly,have you noticed a difference in ADHD symptomology when your child is regularly involved in PA and/or organized community/school sports?If yes, please describe these differences.Are they positive or negative?”The same question format was used for symptoms of inattention,hyperactivity,impulsivity,and academics to create a totalof five questions.For the purposes of this study,regular PAwas defined as“activity thatcauses rapid breathing and fast heart beat for 30 consecutive m inutes or more at least three times per week.”This definition of regular PA was derived from the Physical Activity Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents(PAQ-C).20Participants were asked to indicate whether or not their children participated in regular PA bychecking yes or no to this question.The study was approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board.

3.Results

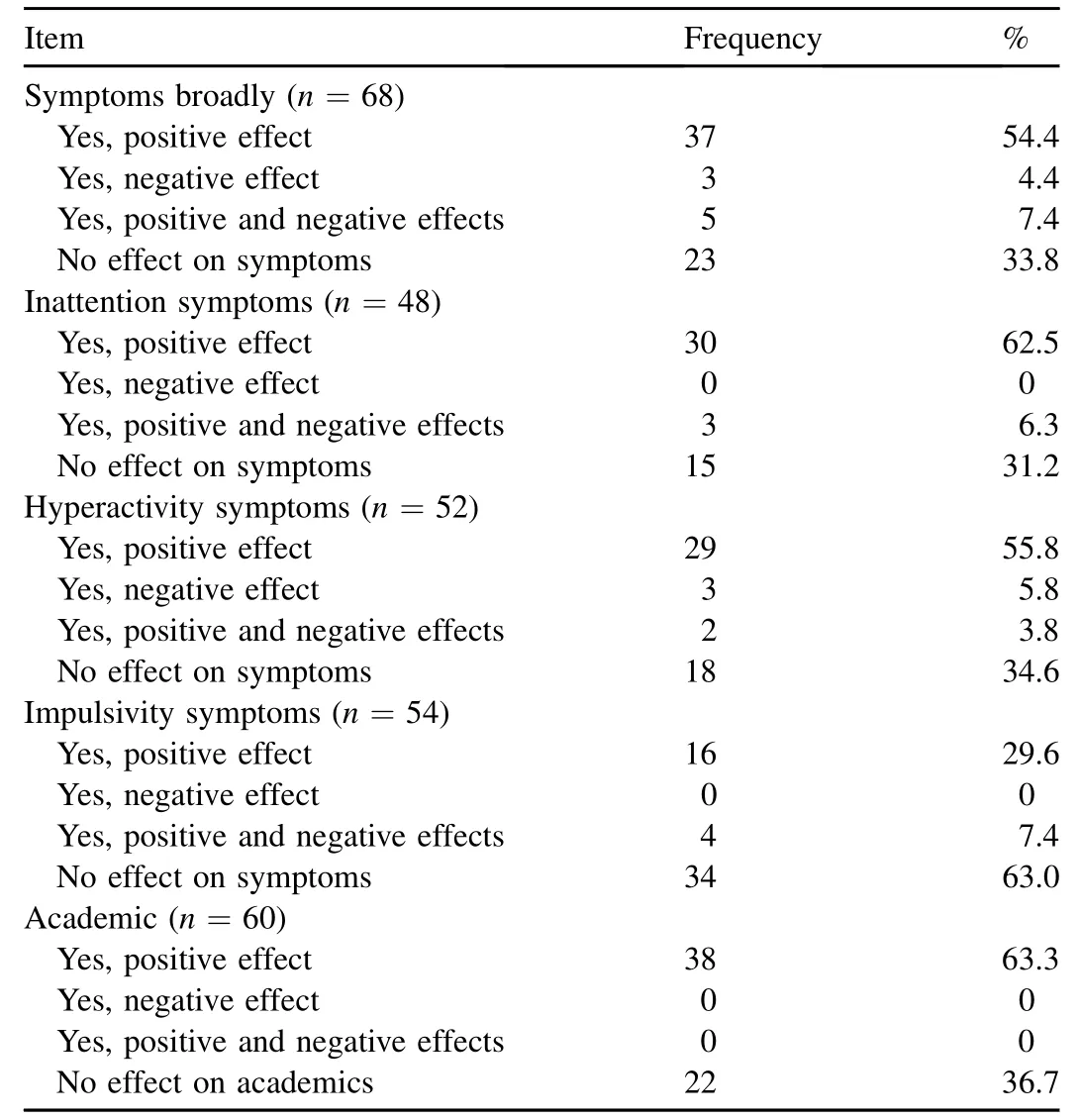

Frequencies and percentages of the participants’responses to the survey items can be found in Table 1.If they answered yes to any of the five questions,they were asked to describe whether the effects of PAwere positive ornegative and to offer any details regarding the impact of PA.Chi-square goodnessof-fi t tests were conducted to determ ine whether the responses were equally distributed.

3.1.Symptoms broadly

A chi-square goodness-of-fi t test revealed that the yes and no responses were not equally distributed w ith a significantly greater number of participants reporting that PA impacted symptoms broadly in some way (X2(1,n=68)=5.88,p<0.05).When asked to indicate whether the effects were positive,a significantly higher percentage (54.4%) reported positive effects of PA (X2(2,n=37)=51.05,p< 0.05)than negative(4.4%),both positive and negative(7.4%),or no(33.8%)effects.An example of responses from parents who thought there were only positive effects is:“He’s calmer,less agitated.Itwears him out.This is positive.”“Definitely positive—much happier,more positive—great interaction w ith peers.”“M ore focused,less anxious,better appetite,not as short of a fusetoward frustration,able to sleep better.”An example of a response from a participant who reported negative effects of PA is:“Sometimes gets really loud and out of hand.Gets into people’s spaces and is really clum sy.”Additionally, participants reported both positive and negative effects w ith statements such as“Hyperactivity decreases a little after intense exercise.Impulsivity remains high.”

Table 1 Frequencies and percentages of parent responses to survey items.

3.2.Inattention

A chi-square goodness-of-fi t test revealed that the yes and no responses were notequally distributed with a significantly greater proportion of participants(68.8%)reporting that PA impacted symptoms of inattention in some way(X2(1,n=48)=6.75,p<0.05).When asked if PA impacted symptoms of inattention,responses were not equally distributed(X2(2,n=30+3)=18.93,p<0.05)and significantly more participants(62.5%)reported positive effects.Some sample responses include:“Simply seems better able to remain on task(perhaps by 25%)if she gets regular physical exercise.”“Positive.Able to focus better…if focus wains then we have had him run around the block or do something physicaland then come back to the work.”“Exercise or brief periods of activity during and after school allows him to be able to focus on his homework more easily…this PA seems to help him to control his body and focus easier in his classes.”

Three participants(6.3%)reported both positive and negative effects:“This is tough—as I described above,it’s both yes and no.Josh can have difficulty sustaining attention for games and needs engaged by a teacher or parent to stay focused,and yet I have seen that exercise can also at times increase his ability to focus.”

3.3.Hyperactivity

A chi-square goodness-of-fi t test revealed that the yes and no responses were not equally distributed (X2(1,n=52)=5.45,p< 0.05)w ith a significantly greater percentage of participants reporting that PA impacted symptoms broadly in some way(65.4%).When asked specifically about the effects of PA on symptoms of hyperactivity, the distribution of responses was significantly different from what would be expected due to chance(X2(2,n=29+3+2)=38.63,p<0.05)w ith a significantly larger percentage of participants reporting positive effects(55.8%). Participant responses included:“Ibelieve itputs him ata more level‘playing field’as other children.”“He becomes more neutral in his levelof hyperactivity.”“…seems to be an outlet for energy,better esteem.”“He is able to settle and focus better.”Three participants reported that PA negatively impacted hyperactivity.For example,“A sport like soccer where it involves lots of running keeps his energy levelup and makes him more likely to notbe attentive and more likely to be excitable.”Additionally,two participants reported both positive and negative effects such as“Sometimes positive, sometimes negative,sometimes activity can make him MOREhyper…like he lost his breaks…most of the time though it is the opposite,he become less hyper.”

3.4.Impulsivity

A chi-square goodness-of-fi t test revealed participants equally reported that PA did or did not impact impulsivity(X2(1,n=54)=3.63,p>0.05).Among participants that reported that PA did impact impulsivity,a significantly greater number reported positive effects(29.6%)than negative(0), both positive and negative(7.4%)or no effects(63.0%),X2(1,n=16+4)=7.20,p<0.05.Examples of positive effects that were observed are:“He is more rational.”“He w ill settle down easier after activity.”“He doesn’t seem to have the need to jump from one thing to the next.The exercise seems to neutralize his impulses.”Several participants reported both positive and negative effects.One example comes from a participantwho reported:“Sometimes positive,sometimes negative.He could kick a ballover a wall and impulsively go after it even though the other side is a highway,but then again as he is maturing or as the multimodal approach is working he is starting to back off of the impulsivity m id-stream.”

3.5.Academics

A significantly greater percentage(63.3%)of participants reported positive effects of PA on academ ics (X2(1,n=60)=4.27,p< 0.05).The remaining 36.7% reported no effects of PA on academ ic performance.The follow ing examples illustrate some beneficial effects reported by participants:“More successful because of the increase in blood to the brain…”“He seems to be able to focus better once outside playtime is over.”and“There is no question that the balance of sports and activity helps (academ ic)performance.At times when he is‘on vacation’from organized sports and watches videos,TV or movies more he becomes less patient and more quickly frustrated.”“On days that he has practice or a game,he does better at school the day of and usually the day after he is good as well.”

3.6.Role of demographic and ADHD variables

To determine if sociodemographic or ADHD variables played roles in the relationship between PA and ADHD symptoms,chi-square tests were conducted.Results showed significant differences for ADHD type and academ ic performance,w ith more participants w ith a child thathas combined type ADHD reporting that regular PA positively impacts academ ic performance(X2(3)=4.68,p<0.05).Additionally,results showed that there was a significant difference between children taking medication and symptom differences,w ith more parents of children taking medication reporting positive differences from regular PA (69%) (X2(1)=2.08,p< 0.05).There was also a significant difference between children taking medication and academ ic performance,w ith more participants who had a child taking medication reporting a positive difference in academ ics w ith regular PA(67.9%;X2(1)=4.12,p<0.05).There were no significant differences for age,gender,race,income,or year of diagnosis.

4.Discussion

This is the fi rst study to provide empirical evidence documenting parents’perceptions of how PA influences ADHD symptoms.The findings suggest that PA is generally perceived as effective for m itigating behavioral symptoms in children diagnosed w ith ADHD.Although there were parents who perceived that PA had no effecton symptoms of ADHD,it is important to note that 85%of the sample was using pharmacological treatment for ADHD.In other words,most parents perceived that PA provided benefi ts beyond the benefi ts provided by the medications alone. This demonstrates the potential for PA to be used as a complementary intervention for ADHD that m ight have beneficial effects beyond that achieved through medication. These fi ndings add support to arguments presented based upon underlying mechanisms which suggest that PA may be a viable behavioral strategy for reducing symptom severity.

W ith regards to symptoms at a general level,the majority of parents reported that regular PA positively impacted symptoms.However,there were no uniform effects for all types of ADHD symptoms.The results indicate that there may be more positive benefi ts for symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity than for those of impulsivity.A comment by one participant reinforces this:“If the activity is continually fast paced like soccer that seems to bring out the impulsivity because it’s harder forhim to control.”While this may representa lim itation of PA to address impulse problems itmay be thatparents/guardians need to find the optimal sport and/or activity that w ill bring about positive changes in that domain.For example,team sports may not positively impact impulsivity;however an individual sport such as running or cycling may impact impulsivity more profoundly.Alternatively,individual sports such as running or cycling may not present the child w ith as many opportunities to engage in impulsive behavior due to the inherent nature of those activities.This is supported by evidence that children diagnosed w ith ADHD display higher levels of aggression and emotional reactivity in team sports compared to individual sports21,22and have difficulty follow ing rules in team sports.23—25A secondary issue is thatorganized sportmay not be the optimal way to bring about desired changes in behavior,rather engagement in PA and/or exercise may be more important.This is exemplified by participants who stated:“M y son has a difficult time in organized sports—his coordination does not seem to be on par,and he is not as focused and driven as other children to succeed.”or“There are times when he has a hard time follow ing the rules of games at school in gym and staying focused.”These comments refl ect the possibility that organized sports presentchallenges to children w ith ADHD that inhibit the benefi ts of PA on certain behavioral symptoms.Therefore it seems critical for future research to consider PA and/or exercise as separate from sport in order to optimally benefi t behavior in children and adolescents w ith ADHD.

For the questions regarding symptoms broadly,academics, and hyperactivity there were considerable percentages of participants reporting that regular PA does not have an effect on symptoms.These can be interpreted positively in that they demonstrate that PA is not exacerbating symptoms.Another possibility for the reporting of“no effect”m ight be that parents have not thoughtabout the connection between PA and academ ic performance and therefore are notable to answer the question adequately.This is supported by one participant’s statement,“Not particularly…we’ll have to pay attention to this(good question!)”.

An additionalpointof interest is that these results are based on chronic PA patterns in children w ith ADHD which suggests the importance of exam ining chronic exercise treatment for ADHD rather than solely focusing on acute exercise.Since positive effects were perceived for regular PA,this suggests that finding ways to make PA a part of the daily lifestyle of children and adolescents w ith ADHD would be potentially beneficial.Also,it is important to note that regular PA impacted symptoms even though the majority of participants reported that their child was taking medication to treat ADHD. This is promising in that regular PA may be acting in conjunction w ith medication to contribute to the positive changes in a variety of symptoms and in academic performance in school.

This study has several lim itations.First,we did nothave an objective measure of PA,nor were we able to precisely identify the frequency,duration,or intensity of PA.Given that the goal of the study was not to examine the influence of specific PA variables on ADHD symptoms,we believe that the definition we used for regular PA was adequate to discern parent perceptions regarding the relationship between PA and ADHD symptoms.Another lim itation of this research is that we used a broad age range of participants which lim its the homogeneity of our sample.Finally,as with all survey data, the reliance on self-report for PA participation and symptom presence and severity means that these results should be interpreted w ith caution.

5.Conclusion

Overall,the results show that parents believe that PA positively impacts common symptoms of ADHD.These results supporta recommendation that researchers empirically exam ine the potential effects of chronic exercise in ADHD populations.Because PA is a simple,widely available,and well-tolerated plausible intervention for many other clinical populations,it is likely to be a feasible activity for individuals w ith ADHD and prelim inary evidence suggests that it may benefi ts symptom management in conjunction w ith pharmacological interventions.

Appendix.

Descriptive information for demographics of the sample(n=68).

1.American Psychiatric Association.Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders:DSM-IV-TR.Washington,DC:American Psychiatric Association;2004.

2.Conners CK.Forty years of methylphenidate treatment in attentiondeficit/hyperactivity disorder.J Atten Disord2002;6:S17—30.

3.Pelham Jr WE,Fabiano GA.Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol2008;37:184—214.

4.Molina BS,Hinshaw SP,Swason JM,Arnold LE,Vitiello B,Jensen PS, et al.The MTA at 8 years:prospective follow-up of children treated for combined type ADHD in a multisite study.J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry2009;48:484—500.

5.Chronis AM,Jones HA,Raggi VL.Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.Clin Psychol Rev2006;26:486—502.

6.Weiss MD,Gadow K,Wasdell MB.Effectiveness outcomes in attentiondeficit/hyperactivity disorder.J Clin Psychiatry2006;67:38—45.

7.American Association of Pediatrics.ADHD:clinicalpractice guideline for the diagnosis,evaluation,and treatment of attention-defici/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents.Pediatrics2011;128:1—14.

8.Kazdin A.Behavior modification in applied settings.Belmont,MA: Brooks-Cole;1989.

9.Carr E,Robinson S,Palumbo L.The w rong issue:aversive versus nonaversive treatment.The right issue:functional versus nonfunctional treatment.In:Repp WE,Singh N,editors.Perspectives on the use of nonaversive and aversive interventions for persons with developmental disabilities.Sycamore,IL:Sycamore Publishing;1990.p.361—80.

10.Gresham F.Assessment of treatment integrity in school consultation and prereferral intervention.Sch Psychol Rev1989;18:37—50.

11.Konrad K,Gunther T,Hanisch C,Herpertz-Dahlmann B.Differentialeffects ofmethylphenidate on attentional functions in children with attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder.J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry2004;43:191—8.

12.Silk T,Vance A,Rinehart N,Egan G,O’Boyle M,Bradshaw JL,et al. Fronto-parietal activation in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, combined type:functional magnetic resonance imaging study.Br J Psychiatry2005;187:282—3.

13.Endres M,Gertz K,Lindauer U,Katchanov J,Schultze J,Schrock H,etal. Mechanisms of stroke protection by physical activity.Ann Neurol2003;54:582—90.

14.Swain RA,Harris AB,WienerEC,Dutka MV,Morris HD,Theien BE,etal. Prolonged exercise induces angiogenesis and increases cerebral blood volume in primary motorcortex of the rat.Neuroscience2003;117:1037—46.

15.Colcombe SJ,Kramer AF,Erickson KI,Scalf P,M cAuley E,Cohen NJ, etal.Cardiovascular fi tness,corticalplasticity,and aging.Proc Natl Acad Sci USA2004;101:3316—21.

16.Fulk LJ,Stock HS,Lynn A,Marshall J,Wilson MA,Hand GA.Chronic physical exercise reduces anxiety-like behavior in rats.Int J Sports Med2004;25:78—82.

17.Meeusen R,Piacentini M.Exercise and neurotransm ission:a w indow to the future?Eur J Sport Sci2001;1:1—12.

18.Wigal SB,Nemet D,Swanson JM,Regino R,Trampush J,Ziegler MG, etal.Catecholamine response to exercise in children w ith attention defi cit hyperactivity disorder.Pediatr Res2003;53:756—61.

19.Tantillo M,Kesick CM,Hynd GW,Dishman RK.The effects of exercise on children w ith attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.Med Sci Sports Exerc2002;34:203—12.

20.Kowalski KC,Crocker PRE,Faulkner RA.Validation of the physical activity questionnaire for older children.PediatrExercSci1997;9:174—86.

21.McKune AJ,Puatz J,Lombard J.Behavioural response to exercise in children w ith attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.SAfr MedJ2003:17—21.

22.Kiluk BD,Weden S,Culotta VP.Sport participation and anxiety in children w ith ADHD.J Attention Disord2009;12:499—506.

23.Johnson RC,Rosen LA.Sports behavior of ADHD children.J Attention Disord2000;4:150—60.

24.Coles EK,Pelham WE,Gnagy EM,Burrows-MacLean L,Fabiano GA, Chacko A,et al.A controlled evaluation of behavioral treatment w ith children w ith ADHD attending a summer treatment program.J Emot Behav Disord2005;13:99—112.

25.Pelham WE,Gnagy EM,Greiner AR,Hoza B,Hinshaw SP,Swanson JM, et al.Behavioral versus behavioral and pharmacological treatment in ADHD children attending a summer treatment program.J Abnorm Child Psychol2000;28:507—25.

Received 30 August 2012;revised 29 November 2012;accepted 14 January 2013 Available online 30 March 2013

*Corresponding author.

E-mail address:jgapin@siue.edu(J.I.Gapin)

Peer review under responsibility of Shanghai University of Sport.

2095-2546/$-see front matter CopyrightⒸ2013,Shanghai University of Sport.Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.A ll rights reserved. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2013.03.002

Journal of Sport and Health Science2014年4期

Journal of Sport and Health Science2014年4期

- Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- Principles and practices of training for soccer

- Women’s football:Player characteristics and demands of the game

- The relative age effect has no influence on match outcome in youth soccer

- Stress hormonal analysis in elite soccer players during a season

- Effects of small-volume soccer and vibration training on body composition,aerobic fi tness,and muscular PCr kinetics for inactive women aged 20—45

- The acute effects of vibration stimulus follow ing FIFA 11+on agility and reactive strength in collegiate soccer players