Principles and practices of training for soccer

Ryland Morgans,Patrick Orme,Liam Anderson,Barry Drust

aLiverpool Football Club,Melwood Training Ground,Deysbrook Lane,Liverpool,L12 8SY,UK

bSchool of Sport,Cardiff Metropolitan University,Cardiff,CF23 6XD,UK

cResearch Institute for Sport and Exercise Sciences,Liverpool John Moores University,Liverpool,L3 3AF,UK

Review

Principles and practices of training for soccer

Ryland Morgansa,b,*,Patrick Ormea,c,Liam Andersona,c,Barry Drusta,c

aLiverpool Football Club,Melwood Training Ground,Deysbrook Lane,Liverpool,L12 8SY,UK

bSchool of Sport,Cardiff Metropolitan University,Cardiff,CF23 6XD,UK

cResearch Institute for Sport and Exercise Sciences,Liverpool John Moores University,Liverpool,L3 3AF,UK

The complexity of the physical demands of soccer requires the completion of a multi-component training programme.The development, planning,and implementation of such a programme are difficultdue partly to the practical constraints related to the competitive schedule at the top level.The effective planning and organisation of training are therefore crucial to the effective delivery of the training stimulus for both individualplayers and the team.The aim of this article is to provide an overview of the principles of training thatcan be used to prepare players for the physical demands of soccer.Information relating to periodisation is supported by an outline of the strategies used to deliver the acute training stress in a soccer environment.The importance of monitoring to support the planning process is also reviewed.

Monitoring;Periodisation;Soccer;Small-sided games;Training

1.Introduction

The physiological demands of soccer are complex.This complexity is partly a consequence of the nature of the exercise pattern.The requirement for frequentchangesin both the speed ofmovement(e.g.,walking,jogging,high intensity running,and sprinting)and direction,makes the activity profi le intermittent. The interm ittent exercise associated w ith soccer necessitates contributions from both the aerobic and the anaerobic energy systems.Training programmes forplayersw illtherefore need to include activities and exercise prescriptions that stress these systems.Players also need to possess muscles that are both strong and flexible.These attributes are important for the successful completion of the technical actions(e.g.,passing, shooting,etc.)which ultimately determ ine the outcome of the match.Effective ways to develop both strength and range of movement,especially in the lower limbs,also needs to be systematically planned and performed in training.

Theneed to includeanumberofcomponentsof fi tnessinto the training programmes of soccer players would indicate that the exercise prescription should be multi-dimensional.The inclusion of specific training plans for the development of a number of energy systemsaswellasspecificmuscleexerciseswould lead to a need for multiple types of physical training sessions.The completion of a large numberof such training sessions is problematic in a sportsuch as soccer forvarious reasons.The need to include training that is focussed on the development/practice of technical skills and sessions that impact on the tactical requirements of soccer prevent the completion of numerous physical training sessions.Technical/tactical sessions are frequently the priority in the training plan and w illtherefore often take precedentoverallother training activities.The large number of competitive fixtures,as well as the need for frequent travel, further limits the time that is available to undertake physical training in thecompetitiveseason.These restrictionspromotethe need for a more global approach to the training of players by devising sessions thatpromote the simultaneous developmentof physical,technical,tactical,and mentalqualities.

The restrictive framework that governs the inclusion of sessions focussed on purely physical conditioning makes planning a priority.Detailed planning of both the acute and chronic physical training sessions ensures that training is efficient in its delivery.This will help to maxim ise the performance improvements associated with the training completed by the players.This article aims to outline the theoreticalapproach used to plan physical training in soccer.It also includes important information on the sport-specific way to deliver a physical training stimulus.A short section on the importance of monitoring the activity completed by players w ill also be included as such strategies are vital to performance,especially for the modern elite player.

2.Planning training for soccer:the im portance of periodisation

Periodisation is a theoreticalmodel thatoffers a framework for the planning and systematic variation of an athlete’s training prescription.1Periodisation was originally developed to support the training process in track and field or sim ilar sports in which there is a clear overall objective such as training tailored towards a major championship such as the Olympics.2The inclusion of variation in the prescribed training load is thought to be a fundamentally important concept in successful training programmes.3This is a consequence of the sustained exposure to the same training load failing to elicit further adaptations.Sustained training loads, especially if they are high,can also lead to mal-adaptations such as fatigue and injury.Both these outcomes would result in ineffective training sessions and a failure to benefi t performance of both the individual athlete and the team.

The variation in training load important for periodisation is obtained by the use of a number of structural units that are used to fulfi l the specific aim(s)associated w ith a training programme.4While the specific term inology to name these units can vary w ithin the literature the nature of the units is inherently similar.The three most important sub-divisions are termed by Cissik4as the phase of training,the macro-cycle, and the micro-cycle.The major difference between these three sub-divisions is the time period associated w ith each other(6—30 weeks for the phase of training;2—6 weeks for a macro-cycle,1 week for a m icro-cycle).This difference in duration enables easier planning as well as an increased flexibility to respond to the athlete(s)reaction to the recently completed training sessions.While different models of periodisation are available(these in simple terms utilise different approaches to vary the training load)they all employ sim ilar structural training units and conceptual approaches to planning.The specific choice of periodisation model w ill be dictated by factors such as the training requirements of the athlete and the competition schedule that is needed to be fulfi lled.5

Despite the popularity of periodisation w ith conditioning coaches in the USA,3there is lim ited research to support this model as the most effective theoretical framework to train athletes especially soccer players.In addition,a lack of evidence prevents the direct application of traditional periodisation models to team sports such as soccer.3These challenges centre around the need for soccer players to attain multiple physical training goals within sim ilar time periods and a competitive fixture schedule that requires multiple (around 40—50)peaks across a large number of months (n=10).While it is clear that some general concepts associated w ith periodisation(for example,the division of the year into phases of training,namely pre-season,the competitive season,and the off-season)are applied within the elite professional game,there is little evidence for the wholesale application of the principles of periodisation.Relatively little information is available,either in the peer reviewed scientific literature or applied professional journals,that provides a detailed outline of the longitudinal training loads experienced by players in soccer.Recent unpublished research from our group6has attempted to characterise such training load patterns in an elite Prem ier League soccer team.The data have illustrated small variations in training load across both phases of training and macro-cycles indicating that the loading patterns completed by these players does not comply w ith that which would be expected if the principles of periodisation was applied.While the data are limited to the training load prescription of one team and its coaches it is likely to reflect a common occurrence w ithin the sport.This is a direct consequence of an inability to systematically manipulate loading patterns across long periods of time due to the requirement to play competitive fixtures in both domestic and international league and cup competitions.Variations in training load are, however,much more frequently seen w ithin the smallest structural planning unit of the m icro-cycle.While the m icrocycle is traditionally associated w ith a 7-day period it can easily be manipulated to reflect the number of days between competitive fixtures.In this way practitioners are able to use the basic principles of periodisation to plan training loads that provide a physical training stimulus to the players as well as facilitate recovery and regeneration from/for competitive matches.

Effective training requires a structured approach to plan the variation in training load albeit across relatively short time periods in soccer.The recognition of a number of key principles when planning facilitates the adaptive process.The importance of progressive overload has already been discussed above.As the improvement in performance is a direct resultof the quantity and quality ofwork completed,a gradual increase in the training load is required to underpin an increase in the body’s capacity to do work.7The progression of load is obtained through subtle changes in factors such as volume(the total quantity of the activity performed),intensity(the qualitative component of the exercise)and the frequency(the number of sessions in a period of time-balance between exercise and recovery)7of training.The approach to such progressions in training should ideally be individualised as each athlete w illbe unique in their currentability and theirpotential to improve.Such individualisation is frequently ignored in team sports such as soccer where the training prescription is often focused on the group.Specificity is widely identified as afundamental factor in shaping the training response.3The term specificity,in the context of training,is related to both the physiological nature of training stimulus and the degree to which training resembles actual competition.3The importance of specificity is based on the notion that the transferof training performance is dependent on the degree to which training replicates the competitive conditions.As such all sessions included in the training programme should have relevance to both the energetic and metabolic requirements and movement patterns of the sport.

3.Practical considerations in delivering soccer-specific training

In order to optimally prepare players to undertake the different positional match demands,specific physical and technical soccer drills and practices that have key physiological objectives need to be regularly implemented.An appropriate training stimulus,to achieve the required physiological objectives,has traditionally been delivered through athletic type running activities.A global training methodology,that incorporates soccer specific activities that not only complementbutphysically contrasteach other,as wellas support the team’s tactical strategy,can promote the development of the technical,tactical,physical,and mental capacities of players simultaneously.

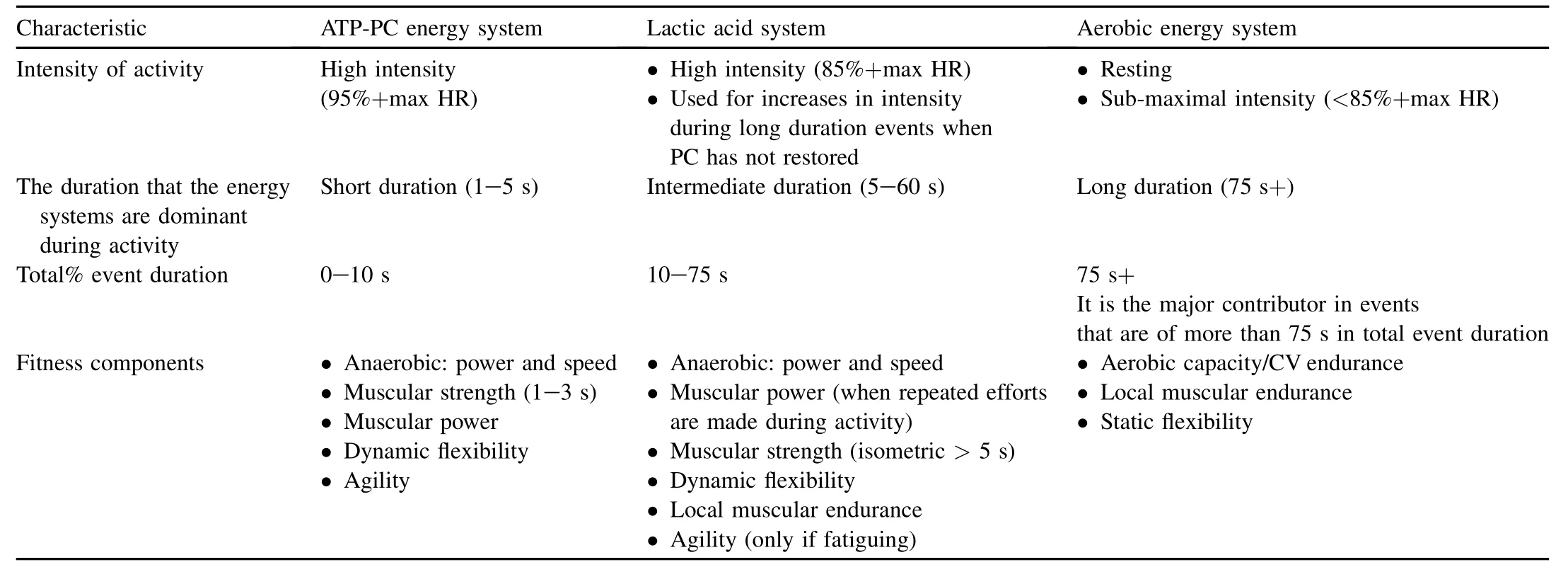

A variety of soccer drills and running protocols have been designed to train metabolic systems important to soccer.These primarily target the development of the aerobic and anaerobic systems.As a consequence the manipulation of running speeds during practices is important(Table 1).The delivery of these practices needs to adhere to basic principles of training,as previously mentioned;frequency,intensity,time,type,specificity,progressive overload,reversibility,and the player’s ability to tolerate training load to ensure fi tness development. A ll conditioning drills,whether soccer specific or running,can achieve a required physical outcome,although the specific choice of drill may be dependent on the philosophy of the manager as much as the conditioning staff.

Of particular interestin the developmentofa globalmethod of training is the utilisation of small-sided games(SSG)as a means of training physical and technical parameters.In using SSG,coaches have the opportunity to maximise their contact time w ith players,increase the efficiency of training,and subsequently reduce the total training time because of their multifunctionalnature.8It is believed that this type of training is particularly beneficial for those elite players who have lim ited training time as a resultof intense fixture schedules.In addition to being an extremely effective use of training time and sport-specific physical load,the use of soccer drills for physiological development may have several advantages over traditional physical training w ithout the ball(running protocols).One of the main differences between traditional and more contemporary soccer-specific training methods is that the presence of the ball during SSG allows the simultaneous improvement of technical and tactical skills.It also provides greater motivation for the players w ithin any given activity.9Nevertheless,players are relatively free during SSG and their effort is highly dependent on their level of individual motivation.During SSG,coaches cannot control the activity levelof their players,and so it is not very clear to whatextent this training modality has on the potential to produce the same physiological responses as short duration intermittent running often produced in matches.This is one of the major lim itations of using such specific forms of training.

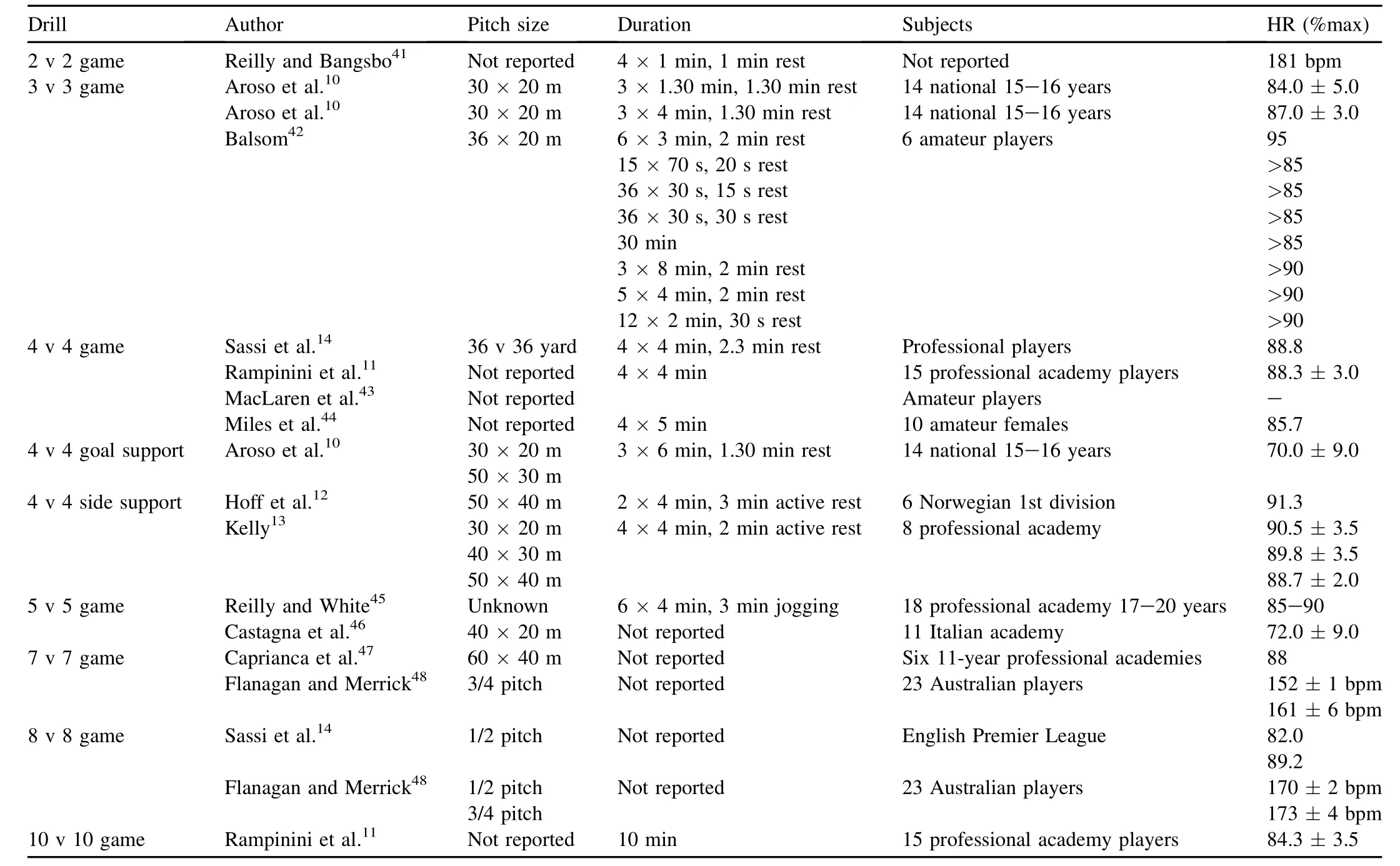

It appears that in general SSG,such as 2 v 2 up to 4 v 4 (plus goalkeepers(GKs))and medium-sided games(MSG), such as 5 v 5 up to 8 v 8(plus GKs),produce intensities that are considered optimal to improving endurance parameters.10—14Practices involving large-sided games(LSG),such as 9 v 9 and 10 v 10(plus GKs),can also result in specific movement patterns that incorporate stretch-shortening-cycle (SSC)activities as well as energy systems that are important to the physiological development for soccer and position-specific capabilities based around the team’s tactical strategy. As training intensity is the primary focus for training adaptations coaches can influence the intensity of SSG through altering the numberof players,pitch size,9,15game rules,9,16,17and/or the duration of individual games(Table 2).The frequency of specific skills thatare performed by the players may also influence the training intensity.16

Table 1 Simple overview of the relationship between different physiological systems and the development of different fi tness components.

3.1.Number of players and pitch size

The general finding in the literature is that as player numbers increase,exercise intensity decreases.This relationship is,however,partly dependent on whether the pitch size also increases.In practices w ith lower player numbers,relatively more time is spentperform ing higher intensity activities such as sprinting,cruising,and turning,while less time is spent standing still.18—20Drills w ith a low number of players involve more continual activity and therefore general activity levels are also high.In drills w ith higher player numbers,and concom itantly larger pitch sizes,movement and physical loadings become more position-specific.If pitch size is not increased as player numbers increase,there is less area per player so the area in which players become involved w ill decrease.Although,these practices w illpromote various types of soccer strength(for example,repeated SSC activity from numerous accelerations and decelerations,isometric strength from shielding the ball)and speed(perception,reaction,and acceleration speed)due to more players on a smaller pitch size,the emphasis(strength or speed)is determ ined by the duration of games(i.e.,>3 min for strength and<3 min for speed).SSG as 4 v 4 on a 30× 20 yard pitch allow for maximum technical involvementand 7 v 7 on a 55×35 yard pitch allow the most ball contacts regardless of playing position.18—20Previous results18—21suggest that SSG(3 v 3 and 4 v 4)allow greater technical developmentw ith more time in possession,more passing,shooting,and 1 v 1 situations than drills w ith more players.Furthermore,it may also be recommended that these lower player number practices completed in small to moderate pitch sizes are most suitable for the development of soccer-specific strength.This is a direct consequence of the repeated bouts of SSC actions acquired through a greater exposure to acceleration and deceleration opportunities.These small/moderate pitch sizes w ill also develop isometric strength through the completion of more opportunities to undertake technical actions such as shielding of the ball.Soccer-specific strength and power w ill also be promoted via a greater number of tackling,heading,and bodily contacts.

LSG w ill provide more specific technical and tactical development for match-play and w ill involve more long-rangepassing and movement patterns such as over/under-lapping forward runs.From a physical perspective,LSG can promote the development of position-specific movement patterns as more opportunities to cover greater distances at submaximal and maximal velocities are provided due to greater pitch size.Examples of such opportunities would include a full-back performing an over-lapping run covering approximately 70—80 yards at 80%of peak running speed.Previous research has shown that SSG elicit higher heart rate(HR) responses and number of ball contacts per game when compared to LSG.22In general,increasing the size of the pitch w ill increase certain physical parameters,namely total distance and high intensity running(>5.5 m/s).The specifics of these changes w ill depend on the positional demands and tactical strategy of the team when in and out of ball possession.The intensity of play(as measured by metres per m in) has also been shown to significantly increase between SSG (198.5 m/m in)and LSG(120.4 m/m in)and the greater intensity of play is associated w ith smaller pitch size,lim ited time in possession23and moderate to high game duration (>5 m in).This decrease in intensity from SSG to LSG has been attributed to fewer opportunities to apply pressure on opponents and greater passing options23due to larger numbers per team,which also lowers total distance.

Table 2 Review of physiological loads associated w ith various soccer training drills.

3.2.Duration of games

Changing the duration of SSG,MSG,or LSG has a corresponding effect on the overall activity and the associated physiological stress.The duration of games w ill determ ine which physical parameters,such as total distance,high intensity distance,intensity(m/m in),total HR,minutes above 85%of maximum HR,number of maximum and medium accelerations and decelerations,w ill increase.Therefore, regardless of other session variables,the duration of games w ill dictate the totalphysical load as more time w illultimately increase any physical parameter monitored.Lim ited studies have investigated the effects of external factors such as duration of game on physical and technical variables.Such investigations would allow a better integration of SSG into the global training process.24Furthermore,the manipulation of the duration of the exercise bout may also elicit changes in quantity and quality of technicalactions aswellas the physical outcomes.24When a 3 v 3(plus GKs)was examined using 2—6 m in games on the same pitch size,there was a significant decrease in intensity,as measured by HR,during the 6 m in game versus the 2 and 4 min games.However,the technical actions were not affected indicating that in practical terms coaches may use game durations ranging from 2 to 6 min w ithoutaffecting the quantity and quality of technical actions whilst gaining a physical stimulus.24

3.3.Monitoring soccer training

Soccer training that has a physical training focus can be described in terms of its process(the nature of the exercise)or its outcome(anatom ical,physiological,biochem ical,and functional adaptations).25—27The training process is relatively easy to evaluate as it is represented by the activity that is prescribed by the coaches(i.e.,conditioning drills,technical drills,or SSG).These aspects of training are also referred to as the external training load.The training outcome is a consequence of this external training load and the associated level of physiological stress that it imposes on any given individual player(which is referred to as the internal training load).25It is particularly important to assess internal training load as it is this component of physical training that actually produces the stimulus for adaptations.25,28In soccer,as the external training load placed on players tends to be sim ilar due to the use of group training sessions,it is important to monitor the internal training load as this w ill vary for any individual player.29This would suggest that it is important to quantify both the externaland internal training load in order to assess the relationship between them30and fully evaluate the training process.

There are a variety of differentmethods that can be used to quantify both the internal and external training load in soccer.31Internal training load measures such as HR assess the cardiovascular stress imposed on players.32,33The validity of HR has been established through substantial research.34,35New technologies such as Global Positioning Systems(GPS) are now frequently used concomitantly with HR to provide a more detailed assessment of the training load placed on players.36,37GPS devices provide a betterunderstanding of the individual training load placed upon the players by enabling detailed data to be collected,such as distance covered and the speed at which these distance are covered.38The accuracy of data that can be collected is dependent on the sampling frequency(5—15 Hz)for both GPS and accelerometer data (~100 Hz).Considerable research has confi rmed the validity of GPS monitoring in soccer training.36,39Other approaches that can be used to evaluate training load are not reliant on expensive technicalequipment.The use of subjective scales to evaluate the individual perception of training intensity such as the rating of perceived exertion(RPE)proposed by Foster et al.40have been w idely used in soccer.These subjective approaches have been validated against various internal and external training load measures26,37and ithas been suggested that these approaches can lead to valid data collation.

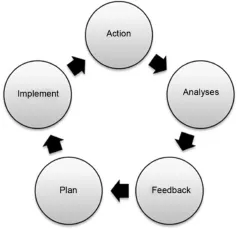

Data obtained through the monitoring of training can be used to enhance training content and subsequently improve performance.This improvement is partly dependent on the effective analysis and feedback to coaches and players. Feedback is a vital part of the coaching process(Fig.1).The methods in which feedback can be delivered can vary significantly and depend on the individual preferences of both coaches and/or players.Reports that include both graphical and/or numerical representations of data are examples of such methods.Reports can also include an analysis of individual exercises(e.g.,conditioning drills,technical practices)w ithin the training session.Modern technology also enables the streaming of“real-time”data allowing the instantaneous monitoring of players’activities during sessions.While such approaches have the potential to be useful in the structuring oftraining sessions as they occur,they are lim ited by the reliability of the data that can be provided.The benefi ts for coaches of such feedback is the ability to adapt the training plan and the management of individual players to improve performance.As such this forms a vital part of the clubs performance strategy.

Fig.1.Diagrammatic representation of the feedback cycle.

1.Brown LE,Greenwood M.Periodization essentials and innovations in resistance training protocols.Strength Cond J2005;27:80—5.

2.Reilly T.The science of training—soccer:a scientific approach to developing strength,speed and endurance.Abingdon:Routledge;2007.

3.Gamble P.Strength and conditioning for team sports:sport-specific physical preparation for high performance.Abingdon:Routledge;2010.

4.Cissik J.Strength and conditioning:a concise introduction.Abingdon: Routledge;2012.

5.Wathen D,Baechle TR,Earle RW.Training variation:periodization.In: Baechle TR,Earle RW,editors.Essentials of strength training and conditioning.Champaign,IL:Human Kinetics;2000.p.519—28.

6.Malone JJ.An examination of the training loads within elite professional football. Liverpool: Liverpool John Moores University; 2014. [Dissertation].

7.Bompa TO.Theory and methodology of training:the key to athletic performance.Kendall:Hunt;1994.

8.Dellal A,Chamari K,Pintus A,Girard O,Cotte T,Keller D.Heart rate responses during small-sided games and short intermittent running training in elite soccer players:a comparative study.J Strength Cond Res2008;22:1449—57.

9.Hill-Haas SV,Dawson BT,Coutts AJ,Rowsell GJ.Physiological responses and time-motion characteristics of various small-sided soccer games in youth players.J Sports Sci2009;27:1—8.

10.Aroso J,Rebelo AN,Gomes-Pereira J.Physiological impact of selected game-related exercises.J Sports Sci2004;22:522.

11.RampininiA,Sassi A,Impellizzeri FM.Reliability of heart rate recorded during soccer training.In:Fifth World Congress of Science and Football. Abingdon:Routledge;2003.

12.Hoff J,W isløff U,Engen LC,Kem i OJ,Helgerud J.Soccer specifi c aerobic endurance training.Br J Sports Med2002;36:218—21.

13.Kelly DM.Physiological and technical responses during 4 v 4 soccer drills on different sized pitches.Liverpool:Liverpool John Moores University;2005.[Dissertation].

14.Sassi R,Reilly T,Impellizzeri F.A comparison of small-sided games and interval training in elite professional soccer players.In:Reilly T,Cabri J, Araujo D,editors.Science and football V.Oxon:Routledge;2005. p.352—4.

15.Kelly DM,Drust B.The effects of pitch dimensions on heart rate responses and technical demands of small-sided soccer games in elite players.J Sci Med Sport2009;12:475—9.

16.Dellal A,ChamariC,Wong DP,AhmaidiS,Keller D,Barros MLR,etal. Comparison of physical and technical performance in European professional soccer match-play:the FA Prem ier League and La LIGA.Eur J Sports Sci2010;25:93—100.

17.Hill-Haas SV,Coutts AJ,Dawson BT,Rowsell GJ.Time-motion characteristics and physiological responses of small-sided games in elite youth players:the infl uence of player number and rule changes.J Strength Cond Res2010;24:2149—56.

18.Platt D,Maxwell A,Horn R,Williams M,Reilly T.Physiological and technical analysis of 3 v 3 and 5 v 5 youth football matches.Insight FA Coaches Assoc J2005;4:23—4.

19.Grant A,W illiams M,Dodd R,Johnson S.Physiological and technical analysis of 11 v 11 and 8 v 8 youth footballmatches.Insight FA Coaches Assoc J1999;2:29—30.

20.GrantA,Williams M,Dodd R,Johnson S.Technicaldemandsof7 v 7 and 11 v 11 youth footballmatches.Insight FA Coaches Assoc J1999;4:26—8.

21.Fenoglio R.The Manchester United 4 v 4 pilot scheme for U9’s.Insight FA Coaches Assoc J2004;3:21—4.

22.Owen AL,Wong DP,M cKenna M,Dellal A.Heart rate responses and technical comparison between small-vs.large-sided games in elite professional soccer.J Strength Cond Res2011;25:2104—10.

23.Owen AL,Wong DP,Paul D,Dellal A.Physical and technical comparisons between various-xided games w ithin professionalsoccer.Int J Sports Med2013;34:1—7.

24.Fanchini M,Azzalin A,Castagna C,Schena F,McCall A, Impellizzeri FM.Effect of bout duration on exercise intensity and technical performance of small-sided games in soccer.J Strength Cond Res2011;25:453—8.

25.Viru A,Viru M.Nature of training effects.In:Garret Jr WE, Kirkendall DT,editors.Exercise and sport science.Philadelphia:Lippincott W illiams Wilkins;2000.p.67—95.

26.Impellizzeri FM,Rampnini E,Coutts AJ,Sassi A,Marcora SM.The use of RPE-based training load in soccer.MedSci SportsExerc2004;36:1042—7.

27.Impellizzeri FM,Rampinini E,Marcora SM.Physiological assessmentof aerobic training in soccer.J Sports Sci2005;23:583—92.

28.Booth FW,Thomason DB.Molecularand cellular adaptation ofmuscle in response to exercise:perspectives of various models.Physiol Rev1991;71:541—85.

29.Manzi V,D’Ottavio S,Impellizzeri FM,Chaouachi A,Chamari K, Castagna C.Profi le of weekly training load in elite male professional basketball players.J Strength Cond Res2010;24:1399—406.

30.Scott BR,Locki RG,Knight TJ,Clark AC,Janse de Jonge XAK.A comparison of methods to quantify the in-season training load in professional soccer players.IntJSportsPhysiolPerform2013;8:195—202.

31.Borresen J,Lambert M I.The quantification of training load,the training response and the effect on performance.Sports Med2009;39:779—95.

32.Achten J,Jeukendrup AE.Heart rate monitoring:applications and lim itations.Sports Med2003;33:517—38.

33.A lexandre D,da Silva CD,Hill-Haas S,Wong del P,Natali AJ,De Lima JR,etal.Heart rate monitoring in soccer:interestand lim its during competitive match play and training,practical application.J Strength Cond Res2012;26:2890—906.

34.Terbizan DJ,Dolezal BA,A lbano C.Validity of seven commercially available heart rate monitors.Meas Phys Educ Exerc Sci2002;6:243—7.

35.Goodie JL,Larkin KT,Schauss S.Validation of the polar heart rate monitor for assessing heart rate during physical and mental stress.Int J Psychophysiol2010;14:159—64.

36.Coutts AJ,Duffield R.Validity and reliability of GPS devices for measuring movement demands of team sports.J Sci Med Sport2010;13:133—5.

37.Casam ichana D,Castellano J,Calleja-Gonzalez J,San Roma´n J, Castagna C.Relationship between indicators of training load in soccer players.J Strength Cond Res2013;27:369—74.

38.Cumm ins C,Orr R,O’Connor H,West C.Global positioning systems (GPS)and m icrotechnology sensors in team sports:a systematic review.Sports Med2013;43:1025—42.

39.Johnston RJ,Watsford ML,Pine MJ,Spurrs RW,Sporri D.Assessmentof 5 Hz and 10 Hz GPS units formeasuring athlete movementdemands.Int J Perform Anal Sport2013;13:262—74.

40.Foster C,Florhaug JA,Franklin J,Gottschal L,Hrovatin LA,Parker S, et al.A new approach to monitoring exercise training.J Strength Cond Res2001;15:109—15.

41.Reilly T,Bangsbo J.Anaerobic and aerobic training.In:Elliot B,editor.Applied sport science:training in sport.Chichester:John Wiley;1998. p.351—409.

42.Balsom P.Precision football.Kempele,Finland:Polar;1999.

43.MacLaren D,Davids K,Isokawa M,Mellor S,Reilly T.Physiological strain in 4-a-side soccer.In:Reilly T,Lees A,Davids K, Murphy WJ,editors.Science and football.London:E&FN Spon; 1988.p.76—80.

44.M iles A,MacLaren D,Reilly T,Yamanaka K.An analysisofphysiological strain in four-a-sidewomen’ssoccer.In:Reilly T,Clarys J,Stibbe A,editors.Science and football II.London:E&FN Spon;1993.p.140—5.

45.Reilly T,White C.Small-sided games as an alternative to interval-training for soccer players.In:Reilly T,Cabri J,Araujo D,editors.Science and football V.Oxon:Routledge;2005.p.355—9.

46.Castagna C,Belardinelli R,Abt G.The VO2and heart rate response to training w ith a ball in youth soccer players.J Sports Sci2004;22:532—3.

47.Caprianca L,Tessitore A,Guidetti L,Figura F.Heart rate and match analysis in pre-pubescent soccer players.J Sports Sci2001;19:379—84.

48.Flanagan T,Merrick E.Holistic training:quantifying the work-load of soccer players.In:Spinks W,Reilly T,Murphy A,editors.Science and football IV.London:Routledge;2002.p.341—9.

Received 22 March 2014;revised 23 May 2014;accepted 2 July 2014 Available online 31 July 2014

*Corresponding author.Melwood Training Ground,Deysbrook Lane,Liverpool,L12 8SY,UK.

E-mail address:ryland.morgans@liverpoolfc.com(R.Morgans)

Peer review under responsibility of Shanghai University of Sport.

2095-2546/$-see front matter CopyrightⒸ2014,Shanghai University of Sport.Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.A ll rights reserved. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2014.07.002

CopyrightⒸ2014,Shanghai University of Sport.Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.All rights reserved.

Journal of Sport and Health Science2014年4期

Journal of Sport and Health Science2014年4期

- Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- Women’s football:Player characteristics and demands of the game

- The relative age effect has no influence on match outcome in youth soccer

- Stress hormonal analysis in elite soccer players during a season

- Effects of small-volume soccer and vibration training on body composition,aerobic fi tness,and muscular PCr kinetics for inactive women aged 20—45

- The acute effects of vibration stimulus follow ing FIFA 11+on agility and reactive strength in collegiate soccer players

- Concussion management in soccer