Concussion management in soccer

Jason P.M ihalik,Robert C.Lynall,Elizabeth F.Teel,Kevin A.Carneiro

aMatthew Gfeller Sport-Related Traumatic Brain Injury Research Center,Department of Exercise and Sport Science,The University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill,NC 27599,USA

bCurriculum in Human Movement Science,Department of Allied Health Sciences,School of Medicine,The University of North Carolina,

Chapel Hill,NC 27599,USA

cInjury Prevention Research Center,The University of North Carolina,Chapel Hill,NC 27599,USA

dDepartment of Physical Medicine&Rehabilitation,The University of North Carolina,Chapel Hill,NC 27599,USA

Concussion management in soccer

Jason P.M ihalika,b,c,*,Robert C.Lynalla,b,Elizabeth F.Teela,b,Kevin A.Carneirod

aMatthew Gfeller Sport-Related Traumatic Brain Injury Research Center,Department of Exercise and Sport Science,The University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill,NC 27599,USA

bCurriculum in Human Movement Science,Department of Allied Health Sciences,School of Medicine,The University of North Carolina,

Chapel Hill,NC 27599,USA

cInjury Prevention Research Center,The University of North Carolina,Chapel Hill,NC 27599,USA

dDepartment of Physical Medicine&Rehabilitation,The University of North Carolina,Chapel Hill,NC 27599,USA

Brain injuries in sports drew more and more public attentions in recent years.Brain injuries vary by name,type,and severity in the athletic setting.Itshould be noted,however,that these injuries are not isolated to only the athletic arena,as non-athletic mechanisms(e.g.,motor vehicle accidents)are more common causes of traumatic brain injuries(TBI)among teenagers.Notw ithstanding,as many as 1.6 to 3.8 m illion TBIresult from sports and recreation each year in the United States alone.These injuries are extremely costly to the globalhealth care system,and make TBI among the most expensive conditions to treat in children.This article serves to define common brain injuries in sport;describe their prevalence,what happens to the brain follow ing injury,how to recognize and manage these injuries,and what you can expect as the athlete recovers.Some return-to-activity considerations for the brain-injured athlete w ill also be discussed.

Concussion;Football;Futbol;Injury management;M ild traumatic brain injury;Soccer

1.Introduction

Soccer is the most popular sport in the world,w ith participation exceeding 265 million people.1Although not considered a full contact sport like American footballor ice hockey, collisions frequently occur in soccerbetween players.It is not uncommon for ball and object(goalposts)to collide w ith players.These collisions often lead to injuries including concussions.The general epidem iology of soccer-related concussions is unknown.In the American collegiate setting,men’s and women’s soccer trails only American footballw ith regard to concussion injury rates,2and concussions in soccer accounts for approximately 5%of total injuries in any given collegiate season.3It is reported over 50,000 concussions occur annually in men’s and women’s high school soccer alone in the United States.2Concussion in high school women’s soccer has been reported ata rate of 3.4 injuries per 10,000 athlete exposures, trailing only high school football,men’s ice hockey,and men’s and women’s lacrosse.4

It has traditionally been thought concussions in soccer occur from player to player collisions involving the upper body of the involved players.5This has led to the adoption of stricter enforcement policies amongst soccer governing bodies in regards to elbow,arm,and head to head contact.It should be noted,however,more recent research has suggested almost one third of soccer related concussions occur after a player deliberately strikes the ball w ith their head.6This is alarm ing as heading is an important soccer skill and is employed up to 800 times in a single season at the professional level.7Due to the prevalence of concussion andcollision nature of soccer,it is imperative for coaches at all age levels to understand the basic principles of proper concussion recognition and management.

2.Definition of concussion

The most common type of sports-related traumatic brain injury(TBI)is cerebral concussion.Although the term concussion is w idely used,there is no universally agreed upon definition of concussion.Despite this,concussions are often defined as a brain injury,induced by biomechanical forces, which results in a complex pathophysiological process affecting the brain.Additionally,the resulting clinical,pathological,and biomechanical features of the injury are often used to define concussion.Concussions are the resultof forces transmitted to the head,through direct contact w ith the head, face,chestorelsewhere on the body.In soccer,another player, the ground,the goal post or the soccer ball itself can create these concussive forces.Concussions often result in rapid,but short-lived,impairment of neurological function.These clinical symptoms are often the result of functional disturbances and not structural injury.Thus,traditional imaging modalities (e.g.,magnetic resonance imaging(MRI)or computed tomography(CT)scans)often result in negative findings when diagnosing a soccer player w ith concussion.8

Concussions are a form of diffuse brain injury,such that concussive injuries result in w idespread disruption of neurologic functioning.A severe type of diffuse brain injury involves damage to the neuronal axons,which may lead to deficits in cognitive functioning such as difficulty remembering or concentrating.In its mostsevere form,diffuse axonal injury can result in the disruption of brainstem centers responsible for heart rate,breathing,and consciousness.9,10However,even w ith this information in m ind,it is important to understand that concussive injuries rarely result in sudden death.Additionally,the overwhelm ing numbers of concussions do not result in a loss of consciousness(LOC).More typically,concussive injuries catalyze a neurometabolic cascade in the brain.It is through this combination of axonal injury and neurometabolic dysfunction that gives rise to the common signs and symptoms associated w ith concussion.

3.Signs and symptom s of concussion

There are many signs and symptoms associated w ith concussive injuries.Signs of concussion are those defi cits that can be observed by other individuals,specifically medical personnel.Concussive symptoms are deficits that we rely on the athlete to report to us.A non-exhaustive list of common concussion signs and symptoms are as follows:headache, nausea,dizziness,vision problems,difficulty concentrating, changes in sleep patterns/drowsiness,emotional changes(irritability,sadness),sensitivity to light/noise,LOC,amnesia (retrograde and/or anterograde),unstable walking/balance problems,general confusion/disorientation,difficulty remembering,vomiting,combativeness,and/or changes in behavior/ personality.While these signs and symptoms are some of the more common deficits post-concussion,it is important to understand that these signs and symptoms 1)are not specific to only concussion,2)do notallhave to be present in order for a concussion diagnosis to be made,and 3)should prompt immediate removal of an athlete from play until such time as they can be evaluated by a medical professional.

LOCand amnesia are often thoughtto be common indicators of concussive injuries,butin reality do notadequately represent the complexity of concussion.LOC occurs in less than 10%of all concussive injuries.11Amnesia,along w ith confusion,is considered to be a hallmark of concussion and may appear directly after the trauma or have a delayed onset.12While LOC and amnesia are relatively rare,these signs may be indicative of more serious brain injury,13and athletes experiencing these signs should be further evaluated to rule out more severe and potentially catastrophic brain injuries.Headache,balance problems,and slow mental processing are the most frequently reported concussion symptoms.14,15Approximately 85%of concussed athletes report a headache after injury,while 77% reportsymptoms of dizziness and balance problems.15

Concussive symptoms are an individualized phenomenon, meaning that the number and severity vary greatly between individuals and are influenced by many factors.While most athletes report symptoms at the time of injury,it can take severalhours after injury for some athletes to feel the onsetof symptoms.8,13,15Therefore,athletes should be monitored carefully during the acute stages of injury in order to properly identify and manage delayed symptoms.While there have been no obvious differences in pre-injury symptom reporting between males and females,16women typically reporta higher frequency and overall symptom severity post-concussion.17Lastly,many concussive symptoms are similar to those of attention deficits disorders,anxiety,or depression.Individuals w ith pre-existing mentalhealth disorders should be monitored carefully because concussions may exacerbate those symptoms.Allof these factors relating to concussive symptoms are importantand may play a role into predicting recovery.While complex,referring the players you suspectof having sustained a concussion to the appropriately trained medicalprofessionals in your jurisdiction w ill help you better care for your athletes.

4.Concussion recognition

The fi rststep in caring forathletes suffering a concussion is recognizing the injury has occurred.Unless the athlete experienced LOC,recognizing a concussion may be a challenging task.It is likely that the athlete w ill appear dazed,dizzy,and disoriented follow ing a concussion.In more obvious injuries, coaches and other personnelmay recognize that the athlete is having difficulty standing on his or her own,or that they are unable to properly follow instructions(e.g.,what play to run, or whatposition to be in).In cases where there are no obvious signs of concussion and the athlete does not immediately reportor recognize symptoms,it is possible for concussions to go undiagnosed at the time of injury.To minim ize this risk,it is imperative for coaches to be welleducated aboutconcussion signs and symptoms,in hopes of being able to recognize themif the athlete is not forthcom ing.Youth coaches who are more educated about concussions are better able to recognize the signs and symptoms,18which decreases the risk of subsequent concussion or potential catastrophic injury for the athlete. Once any concussion signs or symptoms have been identified, the athlete should be removed from the field of play and undergo further evaluation to determine if a concussive injury has occurred.

5.Concussion evaluation

5.1.Examination

Once the decision has been made to remove the athlete from play for a suspected concussion,it is important to conduct a thorough exam ination.This evaluation should include an exam ination of the injured athlete’s cranial nerve function,balance,and cognition.While important to assess all cranial nerves,the exam iner should focus on cranialnerves II, III,and IV in order to elim inate the possibility of a more severe brain injury.Cranial nerve II(optic nerve;visual acuity) is assessed by having the athlete read or identify selected objects at near and far ranges.Cranial nerves III(oculomotor nerve)and IV(trochlear nerve),both of which control eye movement,can be evaluated by determ ining visual coordination and asking the athlete to track a moving object.It is also important to observe the athlete’s pupils to determine if they are equal in size and equally reactive to light.An abnormal testwould result in eitherorboth of the athlete’s pupils failing to constrictwhen a lightsource is pointed directly into them.It is important to recognize thatabnormalmovementof the eyes, irregular changes in pupil size,or atypical reaction to light often indicate increased intracranial pressure,and require an immediate referral to an advanced medical care facility(e.g., emergency room).

It is essential to note the athlete’s condition early in the evaluation process.If they appear to worsen over time,both pulse and blood pressure should be taken.Recognizing an athlete in medical decline is imperative.Developing an unusually slow heart rate or an increased pulse pressure after removal from activity may be signs the athlete is suffering from increasing intracranial pressures.These are important considerations for detecting a more serious and potentially life threatening injury.If any deficiencies are noted during the cranial nerve assessment or the athlete’s condition appears to be worsening rapidly,an emergency medical situation should be assumed and the athlete should immediately be transported to an emergency or neurosurgical department.

It is important to keep in m ind throughout the evaluation that an athlete should never be returned to play on the same day as a suspected concussion.“Suspected”is a keyword,as the examiner should always err on the side of caution and assume a concussion if objective measures are unable to completely rule out the possibility a brain injury has been sustained.Once all potential for life threatening injuries has been ruled out,it is necessary to proceed w ith additional testing to identify potential deficits in balance and/or cognition,as it is possible either of these domains may be affected even in the absence of reported symptoms.19,20

5.2.Objective measures of balance

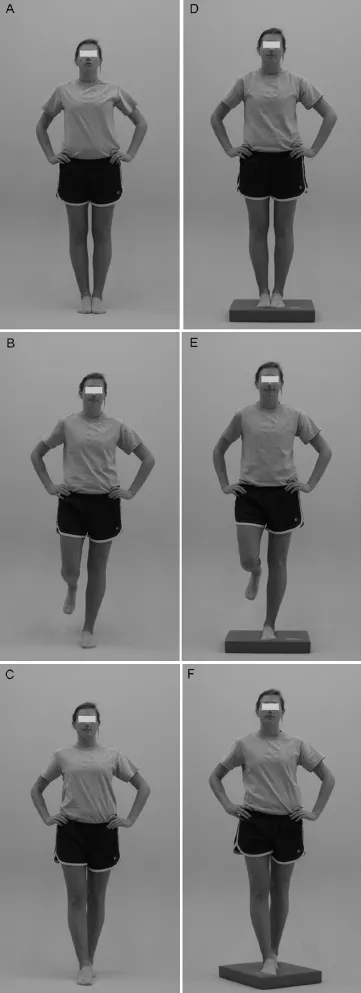

Balance deficits have been shown to persist up to 72-h follow ing concussion.21,22Therefore,it is important to include some measure of balance in a thorough concussion evaluation. The Balance Error Scoring System(BESS)23was developed to provide sports medicine professionals with a rapid and costeffective method of objectively assessing balance in athletes on the sideline orathletic training room follow ing a suspected concussion.The BESS consists of three different stances—double leg,single leg,and tandem—performed on two different surfaces—fi rm and foam—for a total of six conditions(Fig.1).The BESS trials require the athlete to balance for 20 s w ith their eyes closed and hands on their iliac crests. During the single-leg balance tasks,the athlete should balance on their non-dom inant leg(dom inant leg defined as the leg in which the athlete would kick a soccer ball),w ith their contralateral leg in 20°hip flexion and 30°knee flexion. During each of the 20-s tests,athletes should be instructed to stand quietly and motionless in the stance position,keeping their hands on the iliac crests w ith their eyes closed.If the athlete loses their balance at any point during the test,they should make any necessary adjustments and return to the initial testing position as quickly as possible.Participants are scored by adding one error point for each error committed during each of the six balance tasks(w ith a maximum of 10 errors allotted for any single trial).Errors include lifting their hands off their iliac crest,opening their eyes,stepping, stumbling,or falling,moving their non-stance hip into more than 30°abduction,lifting their forefoot or heel,and remaining out of the test position for more than 5 s.It is beneficial to compare this post-injury assessmentof balance to a baseline measure if it is available,although normative data have been published for healthy subjects.24,25

5.3.Objective measures of cognition

Several cost-effective tools have been developed for use on the sideline to screen for potential cognitive deficits follow ing a suspected concussion.The Standardized Assessment of Concussion(SAC)has been developed and validated in the literature as an effective means of assessing cognitive function quickly and easily on the sideline.26,27The SAC requires approximately 6—7 m in to adm inister and assesses four domains of cognition including orientation,immediate memory, concentration,and delayed recall.A composite total score of 30 possible points is summed to provide an overall index of cognitive impairment and injury severity.As practice effects are of concern w ith repeat testing,multiple equivalent forms of the SAC have been developed.The SAC is capable of identifying significant differences between concussed athletes and non-injured controls,and is also capable of distinguishing between pre-season baseline and post-injury scores.28,29

Fig.1.The Balance Error Scoring System consists of three stances(double-leg, single-leg,and tandem)performed on two differentsurfaces(fi rm and foam).

More recently,the Sport Concussion Assessment Tool 3 (SCAT3)and Child-SCAT3 have been developed.8These new tools incorporate the SAC and fi rm-surfaced BESS conditions along w ith several other sideline-based tests including a symptom checklist and coordination exam ination.Both the SCAT3 and Child-SCAT3 take approximately 12—14 min to complete.The Child-SCAT3 is nearly identical to the SCAT3 and was designed for adm inistration to children under 13 years of age.Modifications include a different symptom evaluation and slightchanges to the SAC and BESS.The authors of these tools recommend pre-season baseline testing be performed if possible.

Additionally,another inexpensive clinical tool has recently been established to investigate reaction time follow ing a potential concussion.This clinical measure of reaction time (RTclin)has been shown to be positively correlated with more expensive computer based measures of reaction time30and sensitive to reaction time deficits follow ing concussion.31The RTclininstrumentconsists of a thin,rigid cylinder attached to a weighted disk(e.g.,an ice hockey puck).The instrument is then released and allowed to free fall towards the ground while the athlete is instructed to catch itas quickly as possible.The distance the instrument was allowed to fall is measured, recorded,and converted via mathematical formula into a clinicalmeasure of reaction time.The test takes approximately 3 m in to complete and the RTclininstrument can be manufactured via readily available commercialmaterials by anyone interested in including RTclinin a concussion management program.

Prior to return to full activity,it is necessary to repeat the above battery of tests as thoroughly as possible.While all assessments discussed above are intended to screen athletes suspected of concussion on the sideline immediately follow ing injury,several tools are available which may provide a more in-depth assessment of any lingering deficits even in the absence of reported symptoms.A number of computerized neurocognitive testing platforms have been used to evaluate athletes follow ing concussion.The Automated Neuropsychological Assessment Metrics(ANAM),CNS Vital Signs,Cog-Sport(marketed in North America as Axon Sport), HeadM inder Concussion Resolution Index,and the Immediate Postconcussion Assessmentand Cognitive Test(ImPACT)are all currently available and have demonstrated tolerable reliability and validity.32—37A lthough more expensive and timely to adm inister,the advantages of computerized testing include the ability to assess additional neuropsychological domains (such as processing speed and visual memory),the ability to adm inister baseline testing to large groups of athletes in a short period of time,and the multiple forms used w ithin the testing paradigm to reduce the practice effects.It should also be noted there are many traditional(paper and pencil based) neuropsychological tests available.While these tests collectively take longer to administer,they may be administered w ithout the need for computers or Internet,but do require highly trained personnel.Computerized test manufacturers often advocate the collection of baseline testing;however, recent scientific evidence and consensus recommendationshave questioned the need for this time consum ing and costly process.8,38,39Each organization should carefully consider the need for large scale baseline testing based on available resources.

6.Concussion management

The majority of athletic concussions typically resolve in 5—7 days for collegiate athletes,15,40but on average take longer for high school athletes.41It is important to note these averages represent aggregate data based primarily on college American football players,and may not represent the full recovery spectrum one m ightsee w ith athletes of differing ages and sports.Regardless,it is important to evaluate the athlete regularly throughout the course of recovery w ith graded symptom checklists and objective measures of postural stability and cognition.One in 10 concussions take longer to resolve,and clinicians must recognize that in some cases,it may take weeks or months—or sometimes longer—for symptoms to resolve and for athletes to begin feeling better.It is critical that coaches ensure athletes are fully recovered to protect them from adverse and potentially catastrophic outcomes like second impact syndrome.

Symptoms that can be commonly prolonged for concussed athletes include headaches,dizziness,and mood disturbances. Headaches are notall created equally,and representa complex range of conditions that each requires individualized attention and care.They can range from being so severe that the athlete has a difficult time getting out of bed,to mild tightness and pressure around the head.Bright lights and loud noises may make headaches worse,so coaches should shield players from noisy game environments or night games w ith bright lights if the athletes have these symptoms.Headaches related to concussion may be migraine-like in nature,a tension-type headache,or secondary to cervical spine-related pain or visual disturbances.If a clinician is able to characterize the specific headache type,he or she can initiate the appropriate pharmacological treatment or lifestyle modifications to best enhance recovery.Physical therapy and vision therapy may be indicated in some more severe cases.

Concussions often lead to persistent dizziness,which is another common concussion symptom.Athletes w ill feel dizzy because of a disturbance in their vestibular system, which affects their balance.Athletes w ill often describe feeling“foggy”or unsteady when standing,walking,or changing positions(e.g.,from seated to standing).Dizziness is often successfully treated w ith vestibular rehabilitation and rarely requires pharmacological interventions.Trained physical therapists typically implement vestibular rehabilitation, consisting of gaze and gait stabilization exercises.

If a patient/athlete is experiencing cognitive or mood issues,he or she can experience anxiety,have difficulty paying attention,or become depressed.Sometimes it is necessary to start medical treatment or psychotherapy.42,43Coaches and athletic trainers should keep players engaged w ith team activities,though they should not take part in formalpractice and game play while still recovering.It is important to make the athlete feel like he or she is still“part of the team”to reduce the emotional impact of not getting to be physically involved in the sport.Adequate sleep is also important for cognitive recovery and improved mood.Coaches should be aware that maintaining proper sleep hygiene is one way of regulating sleep.For example,concussed athletes should not be woken up for early morning team meetings at the expense of restful sleep.A number of things can be done during the day to promote sleep hygiene including,butnot lim ited to,waking up at the same time every morning,promoting some sun exposure,exercise as prescribed w ithout worsening symptoms, lim iting television and socialmedia use,and limiting daytime naps.At night,patients should go to bed at the same time everyday,take a warm shower before going to bed,do not go to bed too hungry or too full,avoid television or social media use prior to sleep,sleep in a dark and cool room,and avoid electronic devices and television should the athlete wake during the night.

An important consideration in an overwhelm ing number of concussions is the recognition that a return-to-academ ics often precedes(and is more important)than a return-tosport.Thus,coaches need to be aware of a concussed athlete’s return to the classroom,as their cognitive rehabilitation can impact symptom resolution and their return to athletics. A lthough initially cognitive rest is recommended,managing cognitive exertion is often directed by symptom improvement.The basic tenets of cognitive management are 1)a“slow and steady”return,2)sub-symptom level of activity, and 3)a team approach.The slow and steady“return to learn approach”involves completing schoolwork at home before reintroducing the athlete into a classroom environment.44Athletes should gradually increase their homework to 3 or 4 h daily before returning to the classroom.At school, teachers and professors—and school nurses and counselors when present—should be aware of the student’s situation, and to allow for accommodations as necessary.This m ight include accommodating rest periods during the day,extra time for assignments,extended testing time,excused absences from certain classes and reduced non-essential schoolwork.45Physical education courses should be abandoned until an athlete is clear to return to full physical activity.Initially,cognitive rest typically means a student should avoid activities that cause symptoms.Students should be excused from classes and avoid other forms of cognitive exertion.This means they should avoid activities like reading,watching television,or using electronics until their symptoms improve.As students return to a normal workload, they should try to work in quietand com fortably litspaces to keep symptoms at bay.

In the best situations,the entire academ ic team around a concussed athlete works together to provide an environment conducive to athlete recovery from symptoms in the athlete’s own time.This academic team includes teachers,guidance counselors,schoolnurses,coaches,athletic trainers,and team/ personal physicians and necessitates a cohesive communication network so that all are capable of communicating w ith others.It is paramount that physicians frequently assess anathlete’s progress and make adjustments to the athlete’s management plan accordingly.

As discussed earlier,it can take varied amounts of time to recover from a concussion.With stable post concussive symptoms,athletes can return to a graded exercise program to improve exercise tolerance and even improve symptoms.46Athletes can also begin to exercise w ith team members,but coaches should monitor their heart rate throughout practices. Being able to physically return to their sportw ill likely make athletes happy and boost their overall sense of well-being. Athletes who complete a graded exercise program,followed by the Zurich return to play protocolhave a high likelihood of returning to play successfully.47

7.Return-to-activity progression

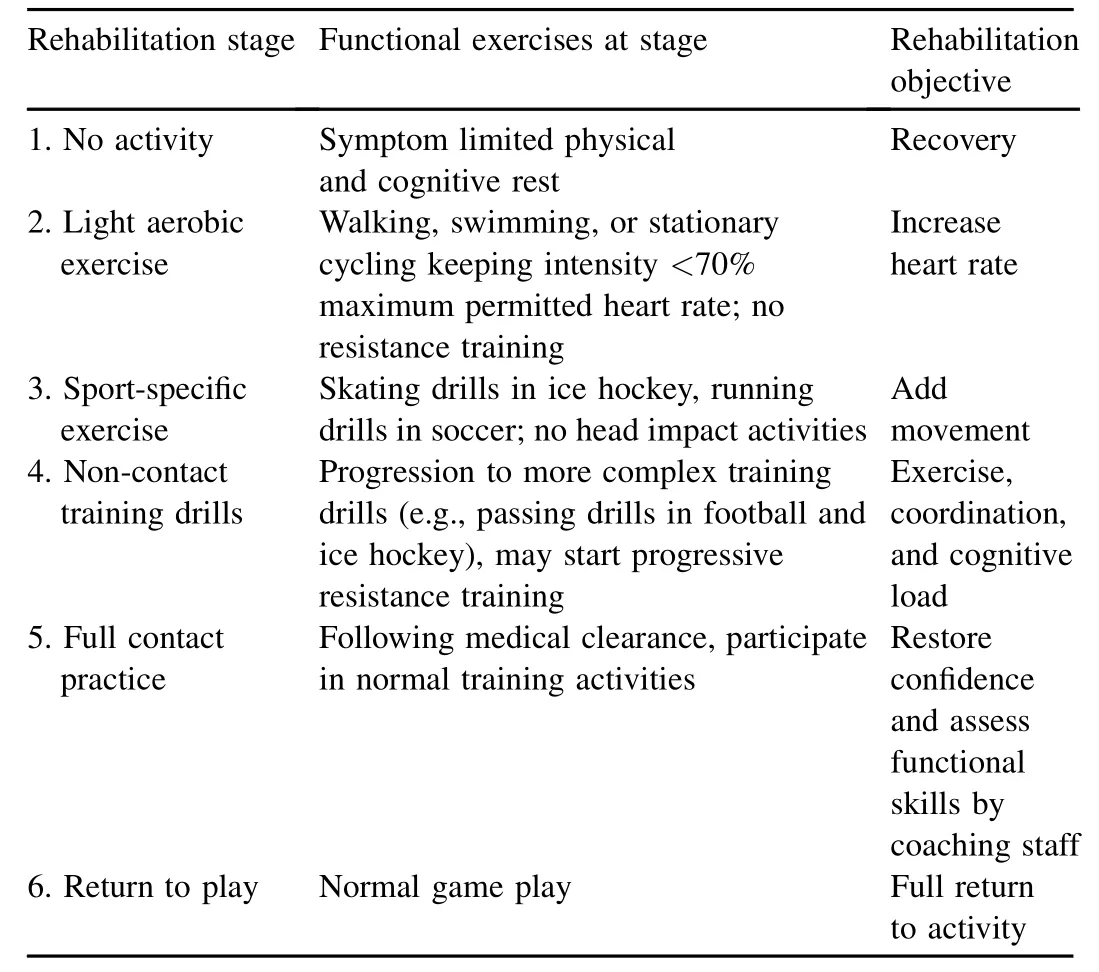

There are many keys to a successful recovery,but the fi rst and most important is that no athlete should return to participation while still symptomatic.Athletes should undergo a stepw ise return-to-activity process once they are symptomfree,and other objective measures(e.g.,balance and cognitive testing)have returned to w ithin normal lim its(Table 1). Each step of the return-to-activity progression should typically take 24 h,allow ing coaches and the sports medicine team time to determ ine whether an athlete’s symptoms were exacerbated during a particular stage.Assum ing no adverse events,the return-to-activity process should take approximately 5—7 days from the time an athlete is deemed symptom-free.

An athlete’s readiness to return-to-activity may be affected by a number of factors.These include the athlete’s previous history of concussion,the nature of the sport(contactvs.noncontact),and whether there are signs the athlete’s condition is deteriorating.In the event of a more serious and potentiallycatastrophic brain injury(i.e.,epiduralorsubduralhematoma), proper management should be supervised by a neurosurgeon, and full clearance to begin a graduated return-to-activity protocol should be authorized by the attending neurosurgeon.These cases are often more complicated than concussions,and decisions as to whether to disqualify athletes from further competition or return them to play safely should be carried out on an individual basis,and only follow ing input from several members of the athlete’s medical team.It is important for coaches and parents to work w ith their athletes’medical professional throughout this return-to-activity process.

Table 1 Typical graduated return-to-activity protocol that begins when athletes report being symptom-free w ith rest and cognitive exertion.8Modified w ith perm ission.

8.Conclusion

The keys to a successful concussion management program are:1)objective evaluation,2)coaches’role in preventing concussion,and 3)importance of medical team.Objective testing methods have evolved over the last 2 decades to offer clinicians a more meaningful way of diagnosing athletes w ith neurological deficits and preventing catastrophic outcomes. Coaches are uniquely positioned to recognize the subtle signs and symptoms of concussions,and to play an integral role in preserving long-term neurological health in their athletes. Coaches must recognize that recovery and return-to-activity considerations involve many factors,and that it may be dangerous to rely solely on symptom self-reports.The presence of trained emergency care providers(e.g.,physicians, athletic trainers,emergency medical services,etc.)is essential to facilitate injury recognition of all soccer injuries including concussion.Coaches must recognize the contributions they can make to promote a safe playing environment,and to enrich an athlete’s injury recovery through sound and conservative approaches to managing potential injuries in sessions they supervise.The recommendations provided herein should not replace the independent evaluation of a physician.A llathletes suspected of suffering from a concussion should be removed from participation and referred to the appropriate medical professional in their respective jurisdiction.

1.Kunz M.265 million playing football.Zurich,Sw itzerland:FIFA;2007. p.5.

2.Gessel L,Fields S,Collins C,Dick R,Comstock RD.Concussions among united states high school and collegiate athletes.JAthl Train2007;42:495—503.

3.Hootman J,Dick R,Agel J.Epidem iology of collegiate injuries for 15 sports:summary and recommendations for injury prevention initiatives.J Athl Train2007;42:311—9.

4.Marar M,McIlvain N,Fields S,Comstock RD.Epidemiology of concussions among united states high school athletes in 20 sports.Am J Sports Med2012;40:747—55.

5.Andersen TE,Arnason A,Engebretsen L,Bahr R.Mechanisms of head injuries in elite football.Br J Sports Med2004;38:690—6.

6.O’Kane JW,Spieker A,Levy MR,Neradilek M,Polissar NL,Schiff MA. Concussion among female m iddle-school soccer players.JAMA Pediatr2014;168:258—64.

7.Matser JT,Kessels AG,Jordan BD,Lezak MD,Troost J.Chronic traumatic brain injury in professionalsoccer players.Neurology1998;51:791—6.

8.M cCrory P,Meeuw isse WH,Aubry M,Cantu B,Dvorak J, Echemendia RJ,etal.Consensus statementon concussion in sport:the 4th international conference on concussion in sportheld in Zurich,November 2012.Br J Sports Med2013;47:250—8.

9.Gennarelli TA.Mechanisms of brain injury.JEmergMed1993;11(Suppl.1):5—11.

10.Schneider RC.Head and neck injuries in football:mechanisms,treatment, and prevention.Baltimore,MD:Williams&Wilkins;1973.

11.Guskiew icz KM,Weaver NL,Padua DA,Garrett Jr WE.Epidem iology of concussion in collegiate and high school football players.Am J Sports Med2000;28:643—50.

12.Kelly JP,Rosenberg JH.Diagnosis and management of concussion in sports.Neurology1997;48:575—80.

13.Halstead ME,Walter KD,American Academy of Pediatrics.Clinical report-sport-related concussion in children and adolescents.Pediatrics2010;126:597—615.

14.Mansell JL,Tierney RT,Higgins M,M cDevitt J,Toone N,Glutting J. Concussive signs and symptoms follow ing head impacts in collegiate athletes.Brain Inj2010;24:1070—4.

15.Guskiew icz KM,M cCrea M,Marshall SW,Cantu RC,Randolph C, Barr W,et al.Cumulative effects associated w ith recurrent concussion in collegiate football players:the NCAA Concussion Study.JAMA2003;290:2549—55.

16.Covassin T,Schatz P,Swanik CB.Sex differences in neuropsychological function and post-concussion symptoms of concussed collegiate athletes.Neurosurgery2007;61:345—50.

17.Harmon KG,Drezner JA,Gammons M,Guskiew icz KM,Halstead M, Herring SA,et al.American Medical Society for Sports Medicine position statement: concussion in sport.BrJSportsMed2013;23:1—18.

18.Valovich M cLeod TC,Schwartz C,Bay RC.Sport-related concussion m isunderstandings among youth coaches.ClinJSportMed2007;17:140—2.

19.Fait P,Swaine B,Cantin JF,Leblond J,M cFadyen BJ.A ltered integrated locomotorand cognitive function in elite athletes 30 days postconcussion: a prelim inary study.J Head Trauma Rehabil2013;28:293—301.

20.Peterson C,Ferrara M,M razik M,Piland S,Elliott R.Evaluation of neuropsychological domain scores and postural stability follow ing cerebral concussion in sports.Clin J Sport Med2003;13:230—7.

21.Guskiew icz KM.Assessment of postural stability follow ing sport-related concussion.Curr Sports Med Rep2003;2:24—30.

22.Guskiew icz KM,Ross SE,Marshall SW.Postural stability and neuropsychological deficits after concussion in collegiate athletes.J Athl Train2001;36:263—73.

23.Riemann BL,Guskiew icz KM,Shields EW.Relationship between clinical and forceplate measures of postural stability.JSport Rehabil1999;8:71—82.

24.Iverson GL,Kaarto ML,Koehle MS.Normative data for the balance error scoring system:implications for brain injury evaluations.Brain Inj2008;22:147—52.

25.Iverson GL,Koehle MS.Normative data for the balance error scoring system in adults.Rehabil Res Pract2013;2013:846418.

26.M cCrea M.Standardized mental status assessment of sports concussion.Clin J Sport Med2001;11:176—81.

27.M cCrea M,Kelly JP,Randolph C,Kluge J,Bartolic E,Finn G,et al. Standardized assessment of concussion(SAC):on-site mental status evaluation of the athlete.J Head Traum Rehabil1998;13:27—35.

28.M cCrea M.Standardized mental status testing on the sideline after sportrelated concussion.J Athl Train2001;36:274—9.

29.M cCrea M,Kelly JP,K luge J,Ackley B,Randolph C.Standardized assessment of concussion in football players.Neurology1997;48:586—8.

30.Eckner JT,Kutcher JS,Richardson JK.Pilotevaluation of a novel clinical testof reaction time in NationalCollegiate Athletic Association Division I football players.J Athl Train2010;45:327—32.

31.Eckner JT,Kutcher JS,Broglio SP,Richardson JK.Effectof sport-related concussion on clinically measured simple reaction time.Br J Sports Med2014;48:112—8.

32.Bleiberg J,Cernich AN,Cameron K,Sun W,Peck K,Ecklund PJ,et al. Duration of cognitive impairment after sports concussion.Neurosurgery2004;54:1073—8.

33.Erlanger D,Saliba E,Barth J,A lmquist J,Webright W,Freeman J. Monitoring resolution of postconcussion symptoms in athletes:preliminary results of a web-based neuropsychological test protocol.J Athl Train2001;36:280—7.

34.LovellMR,Collins MW,Iverson GL,Field M,Maroon JC,Cantu R,etal. Recovery from m ild concussion in high school athletes.J Neurosurg2003;98:296—301.

35.Bleiberg J,Kane RL,Reeves DL,Garmoe WS,Halpern E.Factoranalysis of computerized and traditional tests used in mild brain injury research.Clin Neuropsychol2000;14:287—94.

36.Collie A,Darby D,Maruff P.Computerised cognitive assessment of athletes w ith sports related head injury.BrJSportsMed2001;35:297—302.

37.Collie A,Maruff P,Makdissi M,M cCrory P,M cStephen M,Darby D. Cogsport:reliability and correlation w ith conventionalcognitive testsused in postconcussion medicalevaluations.Clin J Sport Med2003;13:28—32.

38.Schm idt JD,Register-M ihalik JK,M ihalik JP,Kerr ZY,Guskiew icz KM. Identifying impairments after concussion:normative data versus individualized baselines.Med Sci Sports Exerc2012;44:1621—8.

39.Echemendia RJ,Bruce JM,Bailey CM,Sanders JF,Arnett P,Vargas G. The utility of post-concussion neuropsychological data in identifying cognitive change follow ing sports-related MTBIin the absence of baseline data.Clin Neuropsychol2012;26:1077—91.

40.M cCrea M,Guskiewicz KM,Marshall SW,Barr W,Randolph C, Cantu RC,etal.Acute effects and recovery time follow ing concussion in collegiate football players:the NCAA Concussion Study.JAMA2003;290:2556—63.

41.Field M,Collins MW,Lovell MR,Maroon J.Does age play a role in recovery from sports-related concussion?A comparison of high school and collegiate athletes.J Pediatr2003;142:546—53.

42.Petraglia AL,Maroon JC,Bailes JE.From the field of play to the field of combat:a review of the pharmacological management of concussion.Neurosurgery2012;70:1520—33.

43.Reddy CC.Postconcussion syndrome:a physiatrist’s approach.PMR2011;3(Suppl.2):S396—405.

44.Master CL,Gioia GA,Leddy JJ,Grady MF.Importance of“return-tolearn”in pediatric and adolescent concussion.Pediatr Ann2012;41:1—6.

45.M cGrath N.Supporting the student-athlete’s return to the classroom after a sport-related concussion.J Athl Train2010;45:492—8.

46.Leddy JJ,Kozlowski K,Donnelly JP,Pendergast DR,Epstein LH, Willer B.A prelim inary study of subsymptom threshold exercise training for refractory post-concussion syndrome.Clin J SportMed2010;20:21—7.

47.Darling SR,Leddy JJ,Baker JG,W illiams AJ,Surace A, M iecznikowski JC,etal.Evaluation of the Zurich guidelines and exercise testing for return to play in adolescents follow ing concussion.Clin J Sport Med2014;24:128—33.

Received 20 April 2014;revised 3 June 2014;accepted 3 July 2014 Available online 7 August2014

*Corresponding author.Matthew Gfeller Sport-Related Traumatic Brain Injury Research Center,Department of Exercise and Sport Science,The University of North Carolina,Chapel Hill,NC 27599,USA.

E-mail address:jm ihalik@email.unc.edu(J.P.M ihalik)

Peer review under responsibility of Shanghai University of Sport.

2095-2546/$-see front matter CopyrightⒸ2014,Shanghai University of Sport.Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.A ll rights reserved. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2014.07.005

CopyrightⒸ2014,Shanghai University of Sport.Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.All rights reserved.

Journal of Sport and Health Science2014年4期

Journal of Sport and Health Science2014年4期

- Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- Principles and practices of training for soccer

- Women’s football:Player characteristics and demands of the game

- The relative age effect has no influence on match outcome in youth soccer

- Stress hormonal analysis in elite soccer players during a season

- Effects of small-volume soccer and vibration training on body composition,aerobic fi tness,and muscular PCr kinetics for inactive women aged 20—45

- The acute effects of vibration stimulus follow ing FIFA 11+on agility and reactive strength in collegiate soccer players