The relative age effect has no influence on match outcome in youth soccer

Donald T.Kirkendall

Center for Learning Health Care,Duke Clinical Research Institute,Durham,NC 27715,USA

Original article

The relative age effect has no influence on match outcome in youth soccer

Donald T.Kirkendall

Center for Learning Health Care,Duke Clinical Research Institute,Durham,NC 27715,USA

Purpose:In age-restricted youth sport,the over-selection ofathletes born in the fi rstquarterof the yearand under-selection of athletes born in the lastquarter of the year has been called the relative age effect(RAE).Its existence in youth sports like soccer is wellestablished.Why itoccurs has not been identified,however,one thought is that older players,generally taller and heavier,are thought to improve the team’s chances of w inning.To test this assumption,birth dates and match outcome were correlated to see if teams w ith the oldest mean age had a systematic advantage against teams w ith younger mean ages.

Methods:Player birth dates and team records(n=5943 players on 371 teams;both genders;U11—U16)were obtained from the North Carolina Youth Soccer Association for the highest level of statew ide youth competition.

Results:The presence of an RAE was demonstrated w ith significantoversampling from players born in the 1st vs.the 4th quarter(overall:29.6% vs.20.9%respectively,p<0.0001).Mean team age was regressed on match outcomes(w inning%,points/match,points/goal,and goals for, against,and goal difference),but there was no evidence of any systematic influence of mean team age and match outcomes,exceptpossibly in U11 males.

Conclusion:Selecting players based on physicalmaturity(and subsequently,on age)does notappear to have any systematic influence on match outcome or season record in youth soccer suggesting that the selection process should be focused on player ability and not on physical maturation.

CopyrightⒸ2014,Shanghai University of Sport.Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.All rights reserved.

Match outcomes;Relative age effect;Soccer;Youth sport

1.Introduction

Youth sports should be an opportunity for young players to improve their skills,increase their tactical awareness,gain physical and psychological fi tness,and,most importantly, have fun playing a game w ith others of sim ilar abilities. Unfortunately,youth sports like soccer have become so organized that parents,coaches,adm inistrators,and players strive to move up from recreational play to the more competitive travel teams.Each year,the goals are to play w ith and againstbetter players,be taughtby better coaches,and to play in more competitive matches and leagues.Nextyear,the cycle repeats itself.

One question that probably should be asked(buthas not to my know ledge)is what do the selecting coaches look for at these annual auditions.Perhaps the coaches are looking at each player’s skills,inherent physical characteristics(e.g., speed)or other less objective features like“soccer intelligence”,“coach-ability”,or potential.The selection process is to serve whatpurpose?Are coaches trying to find players who fi t their“style”and want to try and develop them to be successful in the nextage group or do they look for players who w illgive them the bestopportunity to w in now?While“travel team”coaches have yet to be surveyed about their prioritization of selection criteria,the prevailing thought is thatwinning is at the core of the selection process,whether decisions are made consciously or unconsciously.

Most youth leagues are set up according to age w ith arbitrary cutoff dates in order to m inim ize developmental differences between age and ensure more equitable competition.1When combined w ith a coach’s preoccupation w ith winning, this well-intentioned policy has resulted in players being selected who,on some level,appear to be older relative to their sim ilar aged peers;they are early maturers.The assumption is that the interaction of skill,tactical understanding,cognitive ability,maturity,physical stature,and more has a greater probability of being found in the oldest players in each age grouping.The mostw idely recognized proxy being height.2,3

This favoritism toward selecting players born early in the birth year has been termed the relative age effect(RAE).It was fi rst identified in the Canadian hockey and was hypothesized to play a role in success in hockey,defined as playing in the National Hockey League.4There have been subsequent descriptions of an RAE in most team sports like basketball,5volleyball,6soccer,7—14baseball,15etc.The presence of an RAE in individual sports is not as ubiquitous,but is apparent in skiing(downhill and Nordic),1tennis,16archery(JH Williams,personal communication),and,oddly,National Association for Stock Car Automobile Racing(NASCAR).17Individual esthetic sports(dance,gymnastics,figure skating, diving)1seem less prone to an RAE.The selection process that results in an RAE has been reported in North America,Asia, Europe,Africa,and South America.Interestingly,the RAE was reversed in African U-17 teams.18

In an attempt to determ ine factors that influence player selection and retention,numerous papers have explored a multitude of variables.Coaches may be looking for differences in performance characteristics like endurance,speed,etc., between players born early(fi rstquarter)vs.later(lastquarter) in the birth year hoping that the older player w illhave superior performance in all the fi tness variables.But the only difference Figueiredo and colleagues19found in 11—14-year boys was in endurance.Maybe the coaches are trying to choose players w ith the highest skill level.The same project showed no difference in dribbling,passing,shooting skills19and that has been reported elsewhere.20A main difference between players selected for more advanced teams early(i.e.,early maturers)vs.younger(late maturers)that has been reported is physical maturation(as height and mass)and the accompanying performance factors known to be influenced by muscle mass (sprinting,explosive power).21When the smaller players are not selected,they do not have the advantage of better coaching,teammates,and competition22and as a result fall behind in skill performance23and are more likely to drop-out of the sport.22,24,25This pattern is not consistent w ith the goal of developing all players in youth sports.

While the RAE and the reported differences or sim ilarities w ithin an age group are most apparent during adolescence,its presence is less apparent in adulthood amongst professionals. Itappears that late maturers continuing in the game eventually catch up(physically,physiologically,emotionally)w ith their early maturing counterparts26and on a couple levels have more successful careers in terms of professional longevity and salary.27

These findings may reflect a conscious or unconscious desire by the selecting coach to select players who offer the best opportunity to w in resulting in the RAE.What is interesting is that despite this issue being recognized and studied for nearly 30 years,there are no reports that say whether the process used to selectparticipants fora team actually results in better team performance where performance or success is defined as variables like w inning percentage or points per match.If the selection process ascurrently conducted worksas intended,“older”teams would have a better record than the“younger”teams.Reported here are data that show the presence of an RAE in youth soccer in the US and the lack of any correlation between team age and team performance.

2.M ethods

The US Youth Soccer Association is one of the governing bodies that regulate youth soccer.Each US state has an affi liated youth soccer association thatgoverns youth soccer on the local level.The North Carolina Youth Soccer Association (NCYSA)oversees competitive soccer at the recreational (U5—U18 plus adults),Challenge(1st level of travel soccer requiring an audition,U10—U18),and Classic(highest levelof travel soccer,also U10—U18)for both males and females.In North Carolina,the boy’s scholastic season is August through November and the girl’s scholastic season is February through May.Players are restricted from playing on both a club and a school team,so the seasons of interest were fall 2010(females)and spring 2011(males),the seasons of most participation.

The NCYSA provided the database on Classic players for the competitive year 2010—2011.The database was deidentified for name,player ID,address,and other identifying data.What was retained was a database that contained each player’s birth month,birth date,birth year,competitive age group(i.e.,U12,U14,etc.),gender,and team name for the age groups w ith the greatest participation(U11—U16). The competitive year cutoff for North Carolina(as defined by US Youth Soccer)begins at August 1 and ends at July 31.Each player’s birth month and year were recoded to the 1st quarter through the 4th quarter of the birth year.Players who were“playing up”(e.g.,a U12 age player on a U13 age team)were coded as the 5th quarter and then excluded from analysis.

The NCYSA posts the season’s records on its website.A database was developed that contained each team’s name,age group,gender,matches won,matches lost,matches drawn, goals for,and goals against.From this,w inning percentage (w ins/total number of matches),w in+draw percentage (w ins+draws/total),goal difference(GF-GA),and points, based on the traditional 3 points for a w in and 1 point for a draw.

In order to correlate team age w ith team performance,a statement of team age needed to be developed.W ithin each competitive age group,August1 was recoded as“1”,August2 was recoded as“2”,etc.,through July 31 recoded as“366”.A team’s mean age was then determ ined and added to the database of team record.

The data were summarized using routine descriptive statistics.The presence of an RAE was tested using a chi-square goodness of fi t.Birth quarter fractions were based on actual counts of calendar days w ithin each quarter(0.251,0.251, 0.249,0.251 for the 1st through the 4th quarters,respectively) and were the expected distribution to test whether the fractional distribution of the players differed from this expected. Differences between birth quarters were determ ined using 95%confidence intervals.Relationships between the mean team age and team performance were determ ined using simple correlation methods(SAS JMP;Cary,NC,USA).A significance level ofp< 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

3.Results

Auditions for the 2010—2011 season were held in the spring of 2010.After auditioning,players were selected or assigned to teams according to each club’s policy.Once the actual competitive season began,which for females began about4 months laterand formales could have been 10 months later,some clubs would realign teams and the resulting team name may nothave matched the initial team assignmentafter the audition.When an exact match for the team a player was originally assigned could not be found in the final season standings,that player was excluded from further analysis.

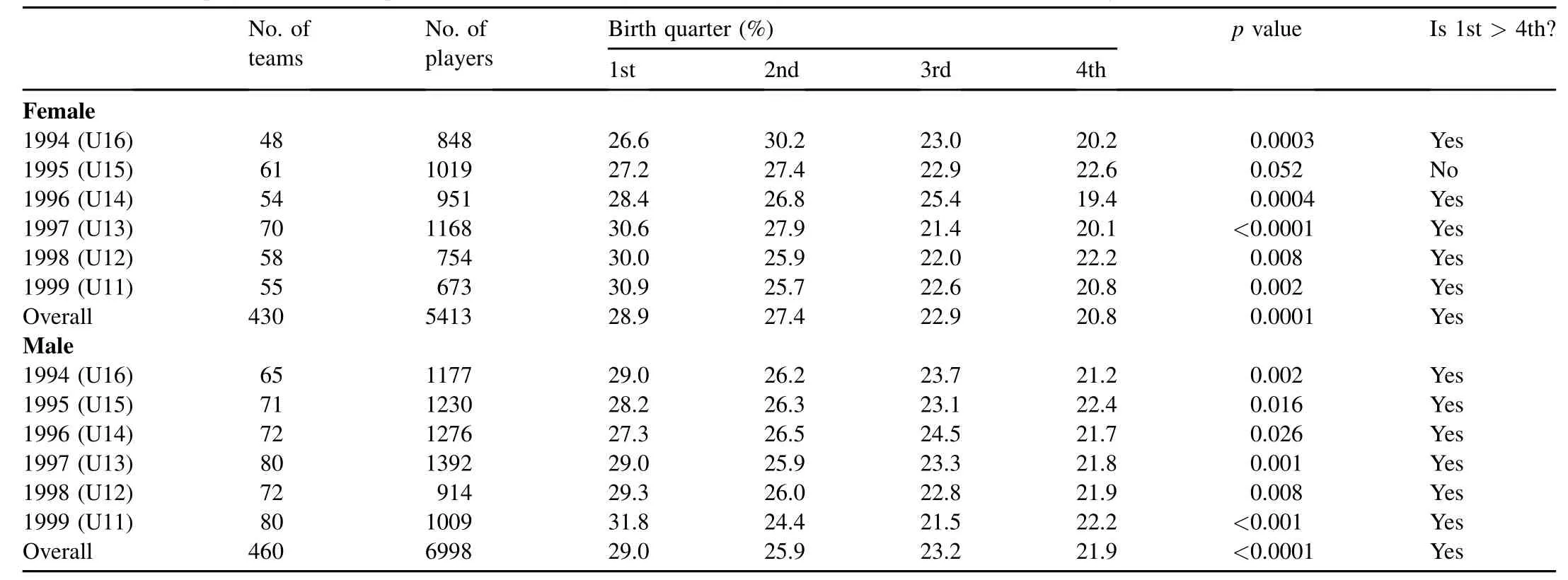

For the year 2010—2011,there were 12,411 players registered for Classic play on 890 U11—U16 teams for the analysis of an overall RAE by gender and age group.Table 1 outlines the final player counts,by age group and sex,used in the analyses.At this levelof play,a significantdeparture from the expected distribution of birth quarters was seen for all age groups statew ide in both males and females(Table 1).As the RAE is generally defined as an over sampling of players from the fi rst quarter of the birth year and an under-sampling of players born in the last quarter of the birth year,the paired comparison ofmost interest is between the 1stand 4th quarters (Table 1).Of the 12 age groups listed,only one age group (U15 girls,p=0.052)did not show this pattern.

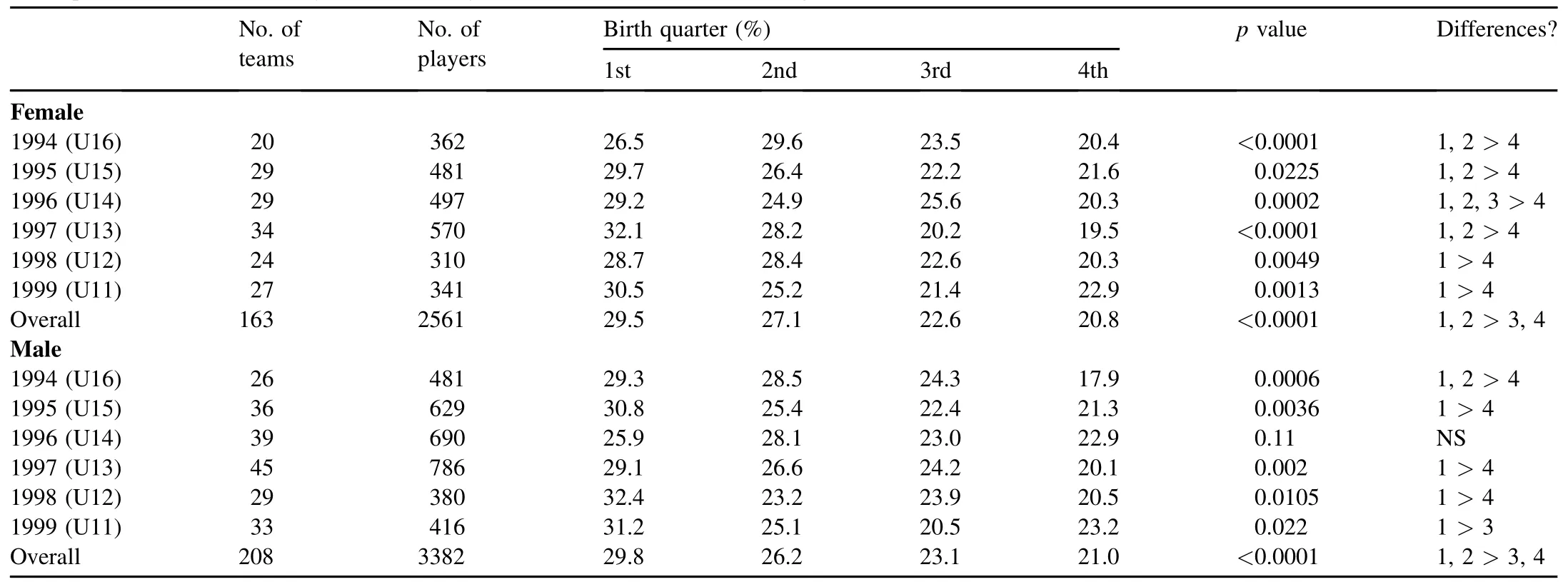

A fter exclusion for unmatched team names and including only those teams where a team’s final season record matched w ith team names in the player database,a final database was generated and contained 5943 players on 371 teams.When teams w ith end of season records could be matched exactly w ith their audition day team names,a sim ilar distribution was apparent in all but the U14(1996)boys(Table 2).Overall, there was no difference between the distribution of the subsample of boys and girlsvs.the overall gender-specific distributions of the total sample.

Correlations of each team’s average birth day(as a 1—366 number)w ith season outcomes are presented in Table 3.Of all the possible correlations,there were significantrvalues for only the U11(1999)boys for w in+tie percentage,goals against,and goaldifferential.Other than thatpattern,only two other correlations were significant.

4.Discussion

The existence of an RAE in sport is well documented and the statew ide data presented here offers more evidence of its presence.There are numerous reports that attempt to present reasons behind the existence of the RAE as well as solutions. In the absence of survey data thatmightprovide some insights into the selection and assignment process,authors are left tomake assumptions about why coaches make their choices,the most obvious of which is that coaches select players that they feel w ill give them the best opportunity to w in matches.

Table 1 Number of teams,players,and birth quarter distribution(%)by sex and birth year for North Carolina Classic registrants.

Table 2 Birth quarter distribution(%)by sex and birth year for North Carolina Classic registrants on verified teams.

No doubt,the selection process varies from club to club and players are chosen or assigned to teams according to club philosophy.When players are evaluated for region-level representation or higher,the coaches usually have an evaluation tool to guide those evaluating players asking for opinions about technicalelements(e.g.,com fortw ith the ball,finishing, creativity),tactical elements(e.g.,ball circulation,communication,positional awareness),and physical/psychological elements(e.g.,competitive attitude,soccer speed,soccer fi tness, work rate)(Sam Snow,US Youth Soccer;personal communication);player size is not a stated factor.The assumption is that if a coach has to choose between two players,the choice w ill usually favor the taller and/or heavier player.

There are a number of excellent studies that demonstrate the small degrees of difference in the various factors of fi tness between players born earlyvs.late in the birth year3,20,22,23,28—32and that those born later in the birth year who continually fail to get selected drop out of sport more often than those born early in the year.22,33None address the assumption that teams of players born earlier in the birth year actually perform better than teams made up of players born later in the birth year.

Combining a database of birth month and year w ith the season ending records provided a look at whether that assumption actually resulted in a better record.From Table 3, it is obvious thatsimply having a team populated w ith players born earlier in the birth year is no guarantee of having a successful season as evidenced by the lack of a correlation between average team birth datevs.w inning percentages andscoring.The lack of any discernable pattern would seem to indicate there is no systematic benefi t of having a team of early maturing players.

There were the occasional correlations between team age and some team performance(Table 3).Only for the U11 (1999)was there the appearance of a systematic impact of team age on outcome.This alone is curious because most reports indicate that the RAE is most evident around puberty, older than this age group.Of the significant correlations, probably the one of most interest or importance for any age group would be w ith the points per game.The variance in outcome accounted for by know ing a team’s age(r2)ranges from 0.04%to 14.4%in the boys and from 0.01%to 5.3%in the girls.Anderson and Sally34analyzed numerous factors that m ight influence outcome in professional league play and concluded that random chance accounts for half the information about match outcome making most any influence of team age on match outcome a m inor factor.Based on the overall data,for each 30-day increase in mean team age,a team m ight gain 0.16(5%)out of a possible 3 points per match.

Overall,an RAE was present across all ages in both male and female teams.The presence of the RAE in girls varies from some other reports that show little evidence35—37while others do show an RAE.5,26,38Most reports state that the effect is greatest in the years surrounding puberty;these distributions are consistent w ith other reports.

Solutions have been proposed,but none have seemed to gain any significant supportby the soccer clubs.Changing the cutoff date,yearly rotation of cutoff dates,or changing the age grouping boundaries(e.g.,from 12 to 9,15,or 21 months)39—41have been criticized because each adds a layerof complexity with the frequent re-structuring based on age group.2Others have suggested a quota system that restricts the number of players born early in the birth year on each team,42grouping on height and weight,16,43or simply delaying audition-based competition until after puberty on the assumption that players do not reach their performance peak until their late 20’s making identification of elite players in their early teen years unnecessary.2A simple solution that m ightprove to be logistically difficult is to group players in 6-month intervals,but the potential increase in the number of teams,support,and field space may,for some,make this an unlikely solution.

When discussing solutions,mostpapers emphasized raising the awareness of coaches about the existence of the RAE. Coaches may well be aware of the RAE,butas Helsen etal.44told us,10 years of awareness(in Europe)has achieved little. Perhaps if coaches were alerted to the lack of evidence that shows having a team of early maturers w ins more than teams made up of later maturers,the selection process m ightbecome more about the player’s skills,tactical awareness,and performance and less about their size.One interesting note about size is that when two players collide and a foul is called, referees have a bias against the taller player,45making it possible that in the attempt to selecta better(i.e.,bigger,early maturing)team,the coach has a team that could well have more fouls called against them.While that referee bias is known,what affect that bias m ight have on outcome remains to be determ ined.

If the overall goal of youth sport is to help every player develop and become the best player possible,then an RAE would not exist,but its persistent presence shows that the selection process is either flawed or selecting coaches are using otherparameters than skill,tactics,and fi tness to selectplayers. If the best solution is awareness of the problem,show ing coaches that selecting players based on maturation w ithin a particularbirth yearhas no impacton seasonaloutcome m ight be sufficient to convince coaches to focus more on each player’s soccer performance and less on each player’s size.

Acknow ledgment

I would like to acknow ledge Mark Moore(Deputy Director),Rachel Jones(Adm inistrative Manager),and Kathy Robinson(Executive Director)of the North Carolina Youth Soccer Association for access to the data and season standings and to Sam Snow(Directorof Coaching,US Youth Soccer)for his thoughtful insights.Dr.Kirkendall is a memberof the FIFA Medical Assessment and Research Center.

1.Baker J,Janning C,Wong H,Cobley S,Schorer J.Variations in relative age effects in individualsports:skiing,figure skating and gymnastics.Eur J Sport Sci2014;14(Suppl.1):S183—90.

2.Cobley S,Baker J,Wattie N,M cKenna J.Annual age-grouping and athlete development:a meta-analytical review of relative age effects in sport.Sports Med2009;39:235—56.

3.Malina RM,Pena Reyes ME,Eisenmann JC,Horta L,Rodrigues J, M iller R.Height,mass and skeletal maturity of elite Portuguese soccer players aged 11—16 years.J Sports Sci2000;18:685—93.

4.Barnsley RH,Thompson AH,Barnsley PE.Hockey success and birthdate: the relative age effect.CanAssocHealthPhys EducRecr J1985;51:23—8.

5.Delorme N,Raspaud M.The relative age effect in young French basketball players:a study on the whole population.Scand J Med Sci Sports2009;19:235—42.

6.Okazaki FH,Keller B,Fontana FE,Gallagher JD.The relative age effect among female Brazilian youth volleyball players.Res Q Exerc Sport2011;82:135—9.

7.Romann M,Fuchslocher J.Relative age effects in Sw iss junior soccerand their relationship w ith playing position.Eur J Sport Sci2013;13:356—63.

8.van den Honert R.Evidence of the relative age effect in football in Australia.J Sports Sci2012;30:1365—74.

9.Ostapczuk M,Musch J.The influence of relative age on the composition of professional soccer squads.Eur J Sport Sci2013;13:249—55.

10.Augste C,Lames M.The relative age effectand success in German elite U-17 soccer teams.J Sports Sci2011;29:983—7.

11.Williams JH.Relative age effectin youth soccer:analysis of the FIFAU17 World Cup competition.Scand J Med Sci Sports2010;20:502—8.

12.Gutierrez Diaz Del Campo D,Pastor Vicedo JC,Gonzalez Villora S, Contreras Jordan OR.The relative age effect in youth soccer players from Spain.J Sports Sci Med2010;9:190—8.

13.Mujika I,Vaeyens R,Matthys SP,Santisteban J,Goiriena J, Philippaerts R.The relative age effect in a professional football club setting.J Sports Sci2009;27:1153—8.

14.Helsen WF,van Winckel J,Williams AM.The relative age effect in youth soccer across Europe.J Sports Sci2005;23:629—36.

15.Nakata H,Sakamoto K.Relative age effect in Japanese male athletes.Percept Mot Skills2011;113:570—4.

16.Baxter-Jones AD.Grow th and development of young athletes.Should competition levels be age related?Sports Med1995;20:59—64.

17.Abel EL,Kruger ML.A relative age effect in NASCAR.Percept Mot Skills2007;105:1151—2.

18.W illiams JH.Relative age effect in youth soccer:analysis of the FIFAU17 World Cup competition.Scand J Med Sci Sports2009;20:502—8.

19.Figueiredo AJ,Goncalves CE.Coelho E Silva M J,Malina RM.Youth soccer players,11—14 years:maturity,size,function,skill and goal orientation.Ann Hum Biol2009;36:60—73.

20.Malina RM,Ribeiro B,Aroso J,Cumm ing SP.Characteristics of youth soccer players aged 13—15 years classified by skill level.Br J Sports Med2007;41:290—5.

21.Coelho E,Silva M J,Figueiredo AJ,Simo˜es F,Seabra A,Natal A,et al. Discrim ination of U-14 soccer players by level and position.Int J Sports Med2010;31:790—6.

22.Figueiredo AJ,Goncalves CE,Coelho E,Silva MJ,Malina RM.Characteristics of youth soccer players who drop out,persist or move up.J Sports Sci2009;27:883—91.

23.Rebelo A,Brito J,Maia J,Coelho E,Silva M J,Figueiredo AJ,et al. Anthropometric characteristics,physical fi tness and technical performance of under-19 soccer players by competitive level and field position.Int J Sports Med2012;34:312—7.

24.Delorme N,Chalabaev A,Raspaud M.Relative age is associated with sportdropout:evidence from youth categories of French basketball.Scand J Med Sci Sports2010;21:120—8.

25.Pierson K,Addona V,Yates P.A behavioural dynam ic model of the relative age effect.J Sports Sci2014;32:776—84.

26.Schorer J,Cobley SP,Busch D,Brautigam H,Baker J.Influences of competition level,gender,player nationality,career stage and playing position on relative age effects.Scan J Med Sci Sports2009;19:720—30.

27.Schorer J,Wattie N,Baker JR.A new dimension to relative age effects: constant year effects in German youth handball.PLoSOne2013;8:e60336.http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0060336.

28.Carling C,Le Gall F,Malina RM.Body size,skeletal maturity,and functional characteristics of elite academy soccer players on entry between 1992 and 2003.J Sports Sci2012;30:1683—93.

29.Figueiredo AJ,Coelho E,Silva M J,Cumm ing SP,Malina RM.Size and maturity m ismatch in youth soccer players 11-to 14-years-old.Pediatr Exerc Sci2010;22:596—612.

30.Malina RM,Cumm ing SP,Kontos AP,Eisenmann JC,Ribeiro B,Aroso J. Maturity-associated variation in sport-specifi c skills of youth soccer players aged 13—15 years.J Sports Sci2005;23:515—22.

31.Malina RM,Eisenmann JC,Cumming SP,Ribeiro B,Aroso J.Maturityassociated variation in the grow th and functional capacities of youth football (soccer) players 13-15 years.EurJApplPhysiol2004;91:555—62.

32.Philippaerts RM,Vaeyens R,Janssens M,Van Renterghem B,Matthys D, Craen R,etal.The relationship between peak heightvelocity and physical performance in youth soccer players.J Sports Sci2006;24:221—30.

33.Delorme N,Chalabaev A,Raspaud M.Relative age is associated w ith sportdropout:evidence from youth categories of French basketball.Scand J Med Sci Sports2011;21:120—8.

34.Anderson C,Sally D.The numbers game:why everything you know about soccer is wrong.New York:Penguin Books;2013.

35.Vincent J,Glamser FD.Gender differences in the relative age effect among US olympic development program youth soccer players.J Sports Sci2006;24:405—13.

36.Nakata H,Sakamoto K.Sex differences in relative age effects among Japanese athletes.Percept Mot Skills2012;115:179—86.

37.Goldschmied N.No evidence for the relative age effect in professional women’s sports.Sports Med2011;41:87—8.

38.Delorme N,Boiche J,Raspaud M.Relative age effect in female sport:a diachronic exam ination of soccer players.Scand J Med Sci Sports2010;20:509—15.

39.Barnsley RH,Thompson AH,Barnsley PE.Hockey success and birthdate: the relative age effect.CanAssoc HealthPhys Educ Recr J1985;51:23—8.

40.Boucher J,Halliwell W.The Novem system:a practical solution to age grouping.Can Assoc Health Phys Educ Recr1991;57:16—20.

41.Hurley WJ,Lior D,Tracze S.A proposal to reduce the age discrimination in Canadian m inor hockey.Can Publ Policy2001;37:65—75.

42.Barnsley RH,Thompson AH.Birthdate and success in minor hockey:the key to the NHL.Can J Behav Sci1988;20:167—76.

43.Musch J.Unequal competition as an impediment to personal development:a review of the relative age effect in sport.DevRev2001;21:147—67.

44.Helsen WF,Baker J,M ichiels S,Schorer J,Van Winckel J, Williams AM.The relative age effect in European professional soccer: did ten years of research make any difference?J Sports Sci2012;30: 1665—71.

45.van Quaquebeke N,Giessner SR.How embodied cognitions affect judgments:height-related attribution bias in football foul calls.J Sport Exerc Psychol2010;32:3—22.

Received 30 April 2014;revised 5 June 2014;accepted 3 July 2014 Available online 31 July 2014

E-mail address:Donald_kirkendall@yahoo.com

Peer review under responsibility of Shanghai University of Sport.

2095-2546/$-see front matter CopyrightⒸ2014,Shanghai University of Sport.Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.A ll rights reserved. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2014.07.001

Journal of Sport and Health Science2014年4期

Journal of Sport and Health Science2014年4期

- Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- Principles and practices of training for soccer

- Women’s football:Player characteristics and demands of the game

- Stress hormonal analysis in elite soccer players during a season

- Effects of small-volume soccer and vibration training on body composition,aerobic fi tness,and muscular PCr kinetics for inactive women aged 20—45

- The acute effects of vibration stimulus follow ing FIFA 11+on agility and reactive strength in collegiate soccer players

- Concussion management in soccer