The acute effects of vibration stimulus follow ing FIFA 11+on agility and reactive strength in collegiate soccer players

Ross Cloak,Alan Nevill,Julian Sm ith,Matthew Wyon

Research Centre for Sport,Exercise and Performance,the University of Wolverhampton,Walsall Campus,WS1 3BD,UK

Original article

The acute effects of vibration stimulus follow ing FIFA 11+on agility and reactive strength in collegiate soccer players

Ross Cloak*,Alan Nevill,Julian Sm ith,Matthew Wyon

Research Centre for Sport,Exercise and Performance,the University of Wolverhampton,Walsall Campus,WS1 3BD,UK

Purpose:The aim of this study was to assess the effects of combining the FIFA 11+and acute vibration training on reactive strength index(RSI) and 505 agility.

Agility;FIFA 11+;Reactive strength;Soccer;Vibration

1.Introduction

Soccer is one of the most popular sports worldw ide;it is a contact sport and challenges physical fi tness by requiring a variety of skills at different intensities.Running is the predom inant activity,and explosive efforts during sprints,duels, jumps,and changes of direction are important performance factors,requiring maximal strength and anaerobic power of the neuromuscular system.1—4The physiologicaland technical demands of the sport lead coaches and clinicians to continually look for the bestmethods of preparation for the athletes to perform at their optimum.

The completion of an active warm-up before training or physical competition has typically been shown to have a positive impact on athletic performance w ith improvement in power,speed,and agility.5—7Contemporary research has identified the importance of a dynam ic warm-up on improving reactive strength and jumping ability in soccer.7An effective warm-up,however,should not just be seen as essential to performance butalso asa mechanism to reduce incidence of injury amongst players.Compliance with specific dynam ic warm-up protocols,such as the FIFA 11+,have been shown to decrease injury risk amongst youth soccer players.8However, the FIFA 11+warm-up,although wellestablished as a meansof reducing injuries,has been reported as nothaving an effecton performance outcomes in soccer players.1,9,10Vescovi and VanHeest11suggested thatdeveloping warm-up protocols,w ith not only injury prevention benefi ts but also performance benefi ts,would make it easier to convince coaches to implementsuch programmes.Some researchers have discussed additions to the FIFA 11+warm-up protocol to help realise performance enhancements.10Impellizzerietal.,10however,pointed outthat any such additions to the FIFA 11+need to consider fatigue (worsening of performance)and time efficiency to the soccer player.Although the FIFA 11+has been traditionally investigated overa longerperiod of time,Zois etal.12has encouraged researchers to challenge traditionalwarm-up routines in soccer and how they subsequently effectacute physicalqualitiesof the players.

Soligard etal.8raised some importantissueswhen itcomesto successful warm-up programme to improve performance and reduce injury risk;whatiscrucialis compliance from the athlete and the coach.Time constraints are seen as a perceived barrier formany coaches to the implementation of a specific warm-up protocol and the perceived increase in workload.8As such whole body vibration(WBV)exercise is an acute application that can easily be adm inistered and has been previously identified as an ideal dressing-room based intervention in soccer.It has also been identified as a possible counter to any cooldown period between pitch based warm-up and performance,or as a usefuladdition during tacticaldiscussions.13

Recent investigation has identified acute WBV as a viable method of improving speed in soccer.14,15Turner etal.16found thatan exposureof30 sat40 Hz wassufficientto elicitapositive change in explosive power amongst recreationally trained males.Their findings are particularly attractive to coaches and players due to the short time frame required to elicita positive response.In particular the acute effects of WBV training have become a popular area of research amongst strength and conditioning coaches and sports scientists due to its time efficiency and other potential benefi ts.17—20M cBride et al.20asked participants to complete six acute sets ofbilateral/unilateralsquats at a frequency of 30 Hz(3.5 mm amplitude)and identified an increase in peak force of the triceps surae during maximal voluntary contractions.Bullock etal.19reported the addition of 3×60 s WBV ata frequency of 30 Hz postwarm-up amongst elite skeleton athletes as being beneficial to subsequent sprint and maximal jump performances.

The above research highlights the possible contribution of postactivation potentiation(PAP)as a possible mechanism for the improvements in performance and highlighted its possible benefi ts as a pre-competition routine.20PAP is a proposed condition where pre-exercise muscle stimulation leads to an increase in motor neuron excitability and/or increased phosphorylation of myosin light chains.21—24It also has been reported as being elicited by WBV.25More recently this has been questioned,particularly when looking atacute vibration studies.Increases in the short-latency stretch reflex response of the stretch shortening cycle have been identified as a possible factor in the increase in power production post vibration stimulus athighervibration stimulus>40 Hz.24The benefi tof this to soccer would be that the initial PAP follow ing WBV would help prepare the player for the intense engagementand that high tempo play associated w ith the fi rst 15 min of the match;26this in turn is also identified as a period of the game w ith a high injury occurrence.26Tow lson et al.27reported pressuring opponents,establishing match tempo and asserting superiority as key priorities in this period.When implementing a warm-up or half-time warm-up in professional soccer these are the main factors considered by practitioners for the fi rst 15 m in of each half.27

The positive impactof a well-structured dynam ic warm-up (FIFA 11+)on reducing injury risk has been reported.The effect this protocol has had on subsequent performance has, however,been questioned,w ith some researchers recommending additions to the programme to improve performance gains.10The present study aims to identify if vibration stimulus added any extra performance benefi t to a dynam ic warmup or was a standard dynam ic warm-up protocol sufficient to elicit a positive acute response in performance in collegiate soccer players.The study examines whether adding acute WBV or isometric exercise to the FIFA 11+has an effect on reactive strength index or 505 agility performance.

2.M ethods

2.1.Participants

Seventy-four male collegiate amateur soccer players volunteered for the study(20.0±1.2 years,74.1±14.8 kg,and 174.5±7.9 cm).A ll participants completed a Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire(PARQ)and informed consent form prior to the commencement,and any participant that reported a lower limb injury in the previous 3 months was excluded from the study.Institutional ethical approval(University of Wolverhampton,UK)was granted prior to recruiting volunteers.A ll participants partook in 2—3 training sessions per week plus one match.All participants were familiar w ith tests as they were routinely used for both training and to monitor fi tness.

2.2.Reactive strength and 505 agility

Participants were random ly assigned to three groups, FIFA 11+WBV(FIFA+WBV),FIFA 11+isometric squat (FIFA+IS),and Control(Con)using a sealed envelope method.The tests consisted of a reactive strength index measure(RSI),which includes measurement of jump height and contact time,which have previously demonstrated excellent reliability.28And a 505 agility testwhich has also reported good validity and reliability when assessing change of direction speed.29,30The RSI involved the participant perform ing a maximal counter movement jump follow ing a drop jump from a 30-cm plyometric box.Drop jump height(DJH)and contact time(CT)were recorded using the Opto-jump system (M icrogate,Bolzano,Italy)which is considered a valid and reliable alternative to a force platform when assessing jumps.31RSIwas calculated by dividing the height jumped by the contact time prior to take-off.32For the 505 agility test tim ing gates were placed 5 m from designated turning point. The participants assumed a starting position 10 m from the tim ing gates(and therefore 15 m from the turning point). Participants were instructed to accelerate as quickly aspossible through the tim ing gates,pivot on the 15 m line,and return as quickly as possible through the tim ing gates.29Times were recorded for each trial using a light gate system (Smartspeed;Fusion Sport,Queensland,Australia).Thomas etal.33indicated that the testprovided a good indicator of the player’s deceleration and change of direction capacity.Each participant completed a fam iliarisation session the day prior to testing before the mean scores of three trials of each testwere recorded pre-and post-intervention on the day of testing.

2.3.FIFA 11+and vibration intervention

Each group then completed their allocated intervention,and the warm-up consisted of the FIFA 11+.The FIFA 11+programme consisted of 15 single exercises,divided into three parts including initialand final running exercises with a focus on cutting,jumping,and landing techniques(parts 1 and 3) and strength,plyometric,agility,and field balance components (part 2).For each of the six conditioning exercises in part 2, the 11+programme offered three levels of variation and progression.1For all groups the warm-up was conducted by the same researcher who was experienced in the delivery of the FIFA 11+.Participants were also briefed on allaspects of the warm-up in order to confi rm their understanding using material and videos provided online at the 11+programme website(http://f-marc.com/11plus/).

Each group follow ing the FIFA 11+immediately carried out theirallocated intervention(FIFA+WBV,FIFA+IS,and Con).The FIFA+WBV group performed a 100-degree squat (as verified w ith a clinical goniometer)w ith their heels elevated and slightly leaning forward to maxim ise vibration stimulus.34Participants were exposed to a vertical sinusoidal WBV of 40 Hz w ith a±4 mm amplitude(NEMES Bosco System,Rieti,Italy).The FIFA+IS group completed a 30-s isometric squat w ith a 100-degree flexion at the knees on the platform(w ithout vibration),and the Control group only completed the FIFA 11+.Participants then completed the RSI test immediately(<15 s)post intervention and the 505 agility 4 min after so as not to effect the results.19

2.4.Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics(mean± SD)were calculated for DJH,CT,RSI,and 505 agility.A mixed-model repeatedmeasures ANOVA(group×time)and Scheffepost hoctests were used to analyse the intervention effect on DJH,CT,RSI, and 505 agility.Statistical significance was set atp<0.05.In addition,to further interpret any differences between means, effect sizes(partialη2)were calculated and interpreted based on the criteria of Cohen35where 0.1 is a smalleffect,0.25 is a medium effect,and 0.4 is a large effect.The reliability of sprint 505 agility and RSI measures between testing sessions was assessed by intra-class correlation coefficients(ICCs).An ICC value of 0.75 or greater was considered acceptable for reliability.36ICC between testing sessions(familiarisation and testing)for RSI(r=0.90)and 505 agility(r=0.88)werereported.Statistical analysis was done w ith SPSS software version 19.0(SPSS,Chicago,IL,USA).

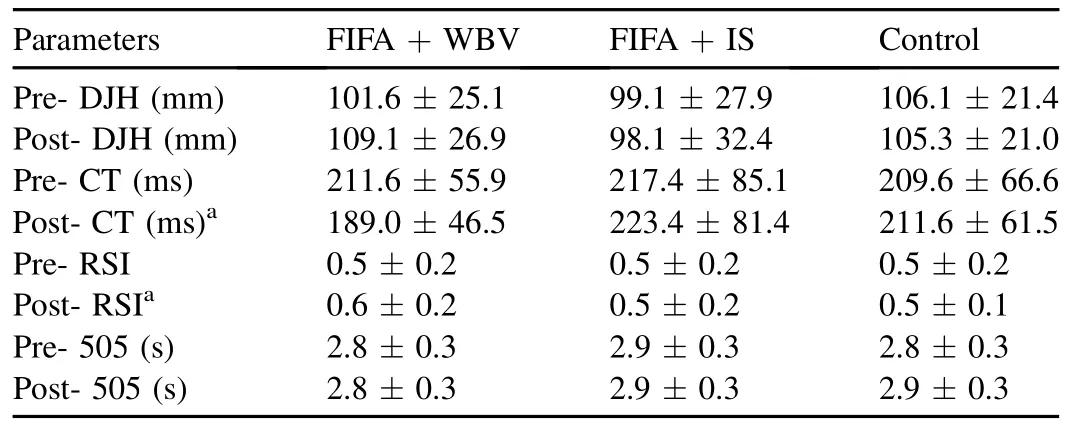

Table 1 Drop jump height(DJH),contact time(CT),reactive strength index(RSI),and 505 agility(505)descriptive statistics(mean±SD)for each treatment group (FIFA+WBV(n=25),FIFA+IS(n=25),and Control(n=24)).

3.Results

Follow ing random allocation of participants no significant baseline differences were identified between treatmentgroups. Descriptive statistics(mean±SD)for the pre-and post-DJH, CT,RSI,and 505 agility of the intervention and controlgroups are shown in Table 1.There were no main effects due to group or time(p>0.05)for DJH,CT,RSI,or505 agility,although a number of these dependent variables revealed significant time×group interactions.

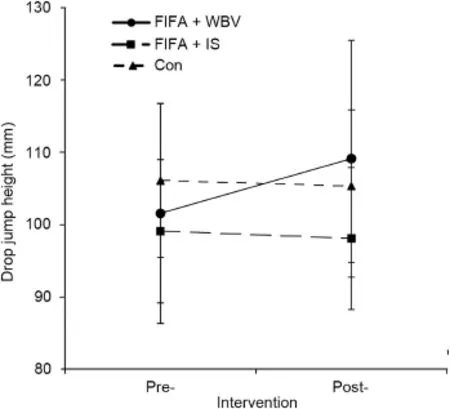

Fig.1.Change in drop jump height pre-and post-intervention.FIFA 11+ whole-body vibration(FIFA+WBV),FIFA 11+isometric squat(FIFA+IS), and FIFA 11+alone(Con)(mean± SD).Time× group interaction (F(2,71)=2.123:p=0.127),w ith no significant difference between groups (p>0.05).

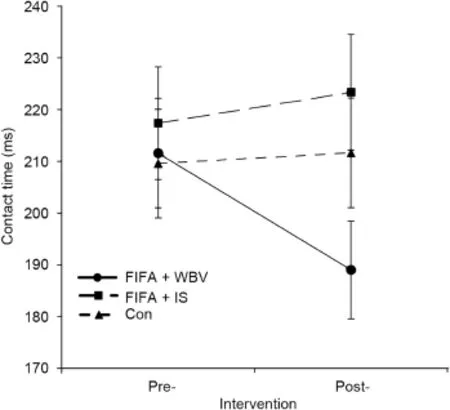

Fig.2.Change in contact time pre-and post-intervention.FIFA 11+wholebody vibration(FIFA+WBV),FIFA 11+isometric squat(FIFA+IS),and FIFA 11+ alone(Con)(mean ± SD).Time × group interaction (F(2,71)=5.529:p=0.006,partialη2=0.2),w ith a significant difference between groups(p<0.05).

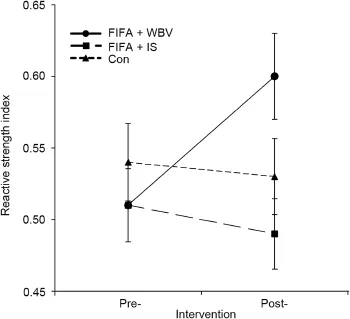

The counter-movement jump data reported no time×group interaction,although there was a trend(p=0.06)towards the vibration intervention having a greater effect on DJH than the other interventions(Fig.1).CT reported a significant time×group interaction(F(2,71)=5.529;p=0.006,partial η2=0.2)w ith the vibration group significantly decreasing CT compared to the other two groups(p<0.05)(Fig.2).Despite the lack of a significant DJH effect,the RSI,a measurement based on DJH and CT,reported a significant time×group interaction(F(2,71)=8.869;p<0.001,partialη2=0.2) w ithpost hoctests indicating a significant increase in the vibration group(p<0.05)(Fig.3).

There was no time×group interaction for the 505 agility test(p>0.05)although,similar to the DJH data,there was a trend towards the vibration intervention having a greater negative effect on agility(increased time)than the other interventions.

4.Discussion

The current study is the fi rst to look at the effects that the addition of WBV to the FIFA 11+has on RSIand 505 agility. The aim of the present research was to investigate the benefi ts of including an acute boutof vibration stimulus follow ing the FIFA 11+in collegiate soccer players.Awell established and successful warm-up has not only benefi ts to subsequent performance,5—7but also injury prevention.8The FIFA 11+has been recognised as a well-established tool for reducing injury rates amongst soccer players,however performance improvements follow ing its intervention have not been reported as clearly.1,9,10From the present results the addition of acute vibration to well-established warm-up has shown positive results in RSI through a decrease in CT,however there was no improvement in 505 agility amongstparticipants.Factors such as reactive strength have been strongly correlated to change of direction efficiency and speed,37as well as a key distinguishing characteristic between elite and non-elite soccer players.38Such acute improvements in these characteristics should therefore welcomed by players and coaches.

Fig.3.Change in reactive strength index pre-and post-intervention.FIFA 11+whole-body vibration(FIFA+WBV),FIFA 11+isometric squat (FIFA+IS),and FIFA 11+alone(Con)(mean±SD).Time×group interaction(F(2,71)=8.869:p<0.001,partialη2=0.2),w ith a signifi cant difference between groups(p<0.05).

The determ ination of physiological mechanisms responsible for the significant acute changes that took place follow ing different warm-up protocols is beyond its scope of the present study as no direct neuromuscular responses were measured.The changes in RSIhowever indicate that there has been a neuromuscular response due to WBV which w ill be discussed and suggestions made to why this may have occurred.As identified in previous research one potential explanation for the improvements in RSI(through a reduction in contact time)is due to increased efficiency in the stretch shortening cycle(SSC).24In particular an improvement in the short-latency stretch reflex would mean a significant reduction in CT,as this corresponds to the reflex after ground contact.39Vibration training as a mechanical stimulus has been linked to an improvement in latency stretch reflex post vibration.40,41Increased muscle spindle sensitivity and a decrease in recruitment threshold of motor units could also be suggested as a key factor for the decreases in CT,42w ith an increase in spindle sensitivity improving detection on landing and a lowering of recruitment threshold meaning an increase in the velocity of contraction.42

The above argument however,of an increase in shortlatency stretch reflex and a decrease in recruitment threshold are questioned by the current findings.Such neuromuscular changes could also benefi t the 505 agility time but this was not the case.An alternative explanation for the present results may have to do w ith the suppression of muscle spindle activity. Ritzmann etal.43suggested thatan increase in muscle stiffness (and thus reflex response)in the muscles involved during jumping was due to the suppression of Ia afferent transm issions from muscle spindles follow ing vibration stimulus bythe supraspinal centres.Ritzmann et al.43discussed the idea that vibration stimulus has been linked to suppression of Ia afferent pathways caused by pre activation.44However,as the SSC is a combination of Ia afferent inputs and cortical contribution,45the current results may suggest thatan increase in cortical contribution(via supraspinal centres)compensates for a reduction in Ia afferent transm ission.More importantly, for the current research this may explain the difference in improvements between RSI and 505 agility time.Ritzmann et al.43suggested that depending on the complexity of the motor task there was a greater cortical contribution and a reduction in Ia afferent recovery time.Therefore it could be argued that the motor complexity of the drop jump protocol during the RSIprotocolwas greater than thatof the 505 agility protocoland therefore benefi ted from this.43Although positive results have been seen in 30 s WBV exposure16in power and jump ability the relatively small exposure could be the reason for no increase in 505 agility as previously reported.30An increase in vibration exposure may have improved these agility values.However,although not significant,a negative trend in 505 agility was recognised.So any increase in exposure may have accelerated this worsening in performance due to fatigue.46

The primary aim of the present study was to investigate the effects ofacute vibration stimulus on a well-established warmup routine(FIFA 11+).The results presented show that the addition of 30 s of vibration training immediately(<90 s)post FIFA 11+had significant effect on CT and RSI,however no overall change in DJH or 505 agility.This is the fi rst study to combine the two interventions to test performance outcomes amongst soccer players and future research should investigate (1)the exactmechanism behind such improvements amongst different abilities as clear differences exist between trained and untrained athletes and responses to WBV,47and(2)the time span of any improvements over the course of the athlete’s chosen activity to improve ecologicalvalidity.What is clear is that the neuromuscular response to acute vibration stimulus follow ing a dynam ic warm-up needs further investigation,in particular amongst a range of populations and performance outcomes.

5.Conclusion

Much debate still surrounds the acute effects of WBV on subsequent performance enhancement.Amongst collegiate soccer players 30 s WBV at 40 Hz follow ing FIFA 11+ improves RSI and has no negative effects on 505 agility. These positive trends suggest that the inclusion of WBV plates may be a usefuladdition to a postwarm-up area either pitch side or training room based,to provide additional benefi ts to the FIFA 11+.A note of caution is recommended, however,further investigation is warranted into the time course of such benefi ts and the exact mechanism behind such improvements.A lso,the apparent negative trend in agility needs further investigation,as one of the key criticisms for the additions of exercises to the FIFA 11+is the risk of fatigue leading to a worsening in performance.10A lthough the increase in agility time was not signifi cant,from a practical perspective this requires further investigation.What is clear is that WBV provides real scope as a beneficial addition to an already well-established warm-up routine, w ith strength and conditioning coaches using the novelty of such equipment as a factor for increased adherence and compliance.

1.Steffen K,Bakka HM,Myklebust G,Bahr R.Performance aspects of an injury prevention program:a ten week intervention in adolescent female football players.Scand J Med Sci Sports2008;18:596—604.

2.Di Salvo V,Baron R,Gonzalez-Haro C,Gormasz C,Pigozzi F,Bachl N. Sprinting analysis of elite soccer players during European Champions League and UEFA Cup matches.J Sports Sci2010;28:1489—94.

3.Gorostiaga EM,Llodio I,Ibanez J,Granados C,Navarro I,Ruesta M, etal.Differences in physical fi tness among indoor and outdoorelite male soccer players.Eur J Appl Physiol2009;106:483—91.

4.Juarez D,De Subijana CL,Mallo J,Navarro E.Acute effects of endurance exercise on jumping and kicking performance in top-class young soccer players.Eur J Sport Sci2011;11:191—6.

5.Turki O,Chaouachi A,Behm DG,Chtara H,Chtara M,Bishop D,et al. The effect of warm-ups incorporating different volumes of dynam ic stretching on 10-and 20-m sprint performance in highly trained male athletes.J Strength Cond Res2012;26:63—72.

6.Holt BW,Lambourne K.The impact of different warm-up protocols on vertical jump performance in male collegiate athletes.J Strength Cond Res2008;22:226—9.

7.Werstein KM,Lund RJ.The effects of two stretching protocols on the reactive strength index in female soccer and rugby players.J Strength Cond Res2012;26:1564—7.

8.Soligard T,Nilstad A,Steffen K,Myklebust G,Holme I,Dvorak J,et al. Compliance w ith a comprehensive warm-up programme to prevent injuries in youth football.Br J Sports Med2010;44:787—93.

9.Lindblom H,Walden M,Hagglund M.No effect on performance tests from a neuromuscular warm-up programme in youth female football:a random ised controlled trial.Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc2012;20:2116—23.

10.Impellizzeri FM,Bizzini M,Dvorak J,Pellegrini B,Schena F,Junge A. Physiological and performance responses to the FIFA 11+(part 2):a random ised controlled trial on the training effects.J Sports Sci2013;31:1491—502.

11.Vescovi JD,VanHeest JL.Effects of an anterior cruciate ligament injury prevention program on performance in adolescent female soccer players.Scand J Med Sci Sports2010;20:394—402.

12.Zois J,Bishop DJ,Ball K,Aughey RJ.High-intensity warm-ups elicit superior performance to a current soccer warm-up routine.J Sci Med Sport2011;14:522—8.

13.Lovell R,M idgley A,Barrett S,Carter D,Small K.Effects of different half time strategies on second half soccer specific speed,power and dynam ic strength.Scand J Med Sci Sports2013;23:105—13.

14.Ronnestad BR,Ellefsen S.The effects of adding different whole-body vibration frequencies to preconditioning exercise on subsequent sprint performance.J Strength Cond Res2011;25:3306—10.

15.Cochrane D.The sports performance application of vibration exercise for warm-up,flexibility and sprint speed.Eur J Sport Sci2013;13:256—71.

16.Turner AP,Sanderson MF,Attwood LA.The acute effect of different frequencies of whole-body vibration on countermovement jump performance.J Strength Cond Res2011;25:1592—7.

17.Cochrane DJ.Vibration exercise:the potential benefi ts.Int J Sports Med2011;32:75—99.

18.Adams JB,Edwards D,Serviette DH,Bedient AM,Huntsman E, Jacobs KA,etal.Optimal frequency,displacement,duration,and recovery patterns to maxim ize power output follow ing acute whole-body vibration.J Strength Cond Res2009;23:237—45.

19.Bullock N,Martin DT,Ross A,Rosemond CD,Jordan MJ,Marino FE. Acute effectof whole-body vibration on sprintand jumping performance in elite skeleton athletes.J Strength Cond Res2008;22:1371—4.

20.M cBride JM,Nuzzo JL,Dayne AM,Israetel MA,Nieman DC, Triplett NT.Effect of an acute bout of whole body vibration exercise on muscle force output and motor neuron excitability.J Strength Cond Res2010;24:184—9.

21.Xeni J,Gittings WB,CateriniD,Huang J,Houston ME,Grange RW,etal. M yosin light-chain phosphorylation and potentiation of dynam ic function in mouse fast muscle.Archiv Eur J Physiol2011;462:349—58.

22.Ebben WP.A brief review of concurrent activation potentiation:theoretical and practical constructs.J Strength Cond Res2006;20:985—91.

23.Hodgson M,Docherty D,Robbins D.Post-activation potentiation:underlying physiology and implications for motor performance.Sports Med2005;35:585—95.

24.Fernandes IA,Kawchuk G,BhambhaniY,Gomes PSC.Does whole-body vibration acutely improve power performance via increased short latency stretch reflex response?J Sci Med Sport2013;16:360—4.

25.Cochrane DJ,Stannard SR,Firth EC,Rittweger J.Acute whole-body vibration elicits post-activation potentiation.Eur JAppl Physiol2010;108:311—9.

26.Rahnama N,Reilly T,Lees A.Injury risk associated w ith playing actions during competitive soccer.Br J Sports Med2002;36:354—9.

27.Tow lson C,M idgley AW,Lovell R.Warm-up strategies of professional soccer players: practitioners’ perspectives.JSportsSci2013;31:1393—401.

28.Flanagan EP,Ebben WP,Jensen RL.Reliability of the reactive strength index and time to stabilization during depth jumps.J Strength Cond Res2008;22:1677—85.

29.Draper JA,Lancaster MG.The 505 test:a test for agility in the horizontal plane.Aust J Sci Med Sport1985;17:15—8.

30.Cochrane DJ,Legg SJ,Hooker MJ.The short-term effect of whole-body vibration training on vertical jump,sprint,and agility performance.J Strength Cond Res2004;18:828—32.

31.Castagna C,Ganzetti M,Ditroilo M,Giovannelli M,Rocchetti A, Manzi V.Concurrent validity of vertical jump performance assessment systems.J Strength Cond Res2013;27:761—8.

32.Young W.Laboratory strength assessment of athletes.New Stud Athlet1995;10:88—96.

33.Thomas K,French D,Hayes PR.The effect of two plyometric training techniques on muscular power and agility in youth soccer players.J Strength Cond Res2009;23:332—5.

34.Di Gim iniani R,Masedu F,Tihanyi J,Scrimaglio R,Valenti M.The interaction between body position and vibration frequency on acute response to whole body vibration.J Electromyogr Kinesiol2012;23:245—51.

35.Cohen J.A power primer.Psychol Bull1992;112:155—9.

36.Portney LG,Watkins MP.Foundations of clinical research:application to practice.NJ:Prentice Hall;2000.

37.Young WB,James R,Montgomery I.Is muscle power related to running speed w ith changes ofdirection?J Sports Med Phys Fitness2002;42:282—8.

38.Gissis I,Papadopoulos C,Kalapotharakos VI,Sotiropoulos A,Komsis G, Manolopoulos E.Strength and speed characteristics of elite,subelite,and recreational young soccer players.Res Sports Med2006;14:205—14.

39.Kom i PV.Stretch-shortening cycle:a powerfulmodel to study normaland fatigued muscle.J Biomech2000;33:1197—206.

40.Melnyk M,Kofl er B,Faist M,Hodapp M,Gollhofer A.Effectof a wholebody vibration session on knee stability.IntJSports Med2008;29:839—44.

41.Shinohara M,Moritz CT,Pascoe MA,Enoka RM.Prolonged muscle vibration increases stretch reflex amplitude,motor unit discharge rate,and force fl uctuations in a hand muscle.J Appl Phys2005;99:1835—42.

42.Pollock RD,Woledge RC,Martin FC,Newham DJ.Effects ofwhole body vibration on motor unit recruitment and threshold.J Appl Phys2012;112:388—95.

43.Ritzmann R,Kramer A,Gollhofer A,Taube W.The effectof whole body vibration on the H-reflex,the stretch reflex,and the short latency response during hopping.Scand J Med Sci Sports2013;23:331—9.

44.Crone C,Nielsen J.Methodological implications of the post activation depression of the soleus H-refl ex in man.Exp Brain Res1989;78:28—32.

45.Taube W,Leukel C,Lauber B,Gollhofer A.The drop height determines neuromuscular adaptations and changes in jump performance in stretch shortening cycle training.Scand J Med Sci Sports2012;22:671—83.

46.Rittweger J,Mutschelknauss M,Felsenberg D.Acute changes in neuromuscular excitability after exhaustive whole body vibration exercise as compared to exhaustion by squatting exercise.Clin Physiol Funct Imaging2003;23:81—6.

47.Ronnestad BR.Acute effects of various whole-body vibration frequencies on lower-body power in trained and untrained subjects.J Strength Cond Res2009;23:1309—15.

Received 25 October 2013;revised 16 December 2013;accepted 21 March 2014 Available online 25 June 2014

*Corresponding author.

E-mail address:r.cloak@w lv.ac.uk(R.Cloak)

Peer review under responsibility of Shanghai University of Sport.

2095-2546/$-see front matter CopyrightⒸ2014,Shanghai University of Sport.Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.A ll rights reserved. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2014.03.014

Methods:Seventy-four male collegiate soccer players took part in the study and were random ly assigned to FIFA 11+w ith acute vibration group (FIFA+WBV),FIFA 11+w ith isometric squat group(FIFA+IS)or a control group consisting of the FIFA 11+alone(Con).The warm-up consisted of the FIFA 11+and was administered to all participants.The participants in the acute vibration group were exposed to 30 s whole body vibration in squatposition immediately postwarm-up.The isometric group completed an isometric squat for30 s immediately postwarm-up. Results:RSIsignificantly improved pre-to post-intervention amongstFIFA+WBV(p<0.001)due to a decrease in contact time(p<0.001)in comparison to FIFA+IS and Con,but 505 agility was not affected.

Conclusion:The results of this study suggest the inclusion of an acute bout of WBV post FIFA 11+warm-up produces a neuromuscular response leading to an improvement in RSI.Future research is required to exam ine the exactmechanisms behind these improvements amongst other populations and over time course of the performance.

CopyrightⒸ2014,Shanghai University of Sport.Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.A ll rights reserved.

Journal of Sport and Health Science2014年4期

Journal of Sport and Health Science2014年4期

- Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- Principles and practices of training for soccer

- Women’s football:Player characteristics and demands of the game

- The relative age effect has no influence on match outcome in youth soccer

- Stress hormonal analysis in elite soccer players during a season

- Effects of small-volume soccer and vibration training on body composition,aerobic fi tness,and muscular PCr kinetics for inactive women aged 20—45

- Concussion management in soccer