Women’s football:Player characteristics and demands of the game

Vness Mrtı´nez-Lguns,Mrgot Niessen,Ulrich Hrtmnn

aInstitute of Movement and Training Science,University of Leipzig,Leipzig,04109,Germany

bFaculty of Kinesiology and Recreation Management,University of Manitoba,Winnipeg,R3T 2N2,Canada

Women’s football:Player characteristics and demands of the game

Vanessa Martı´nez-Lagunasa,b,*,Margot Niessena,Ulrich Hartmanna

aInstitute of Movement and Training Science,University of Leipzig,Leipzig,04109,Germany

bFaculty of Kinesiology and Recreation Management,University of Manitoba,Winnipeg,R3T 2N2,Canada

The number of scientific investigations on women’s football specific to the topics of player characteristics and demands of the game has considerably increased in recentyears due to the increased popularity of the women’s game worldw ide,although they are notyetas numerous as in the case of men’s football.To date,only two scientific publications have attempted to review the main findings of studies published in this area.However,one of them was published about20 years ago,when women’s footballwas still in its infancy and there were only a few studies to reporton.The other review was more recent.Nonetheless,its main focus was on the game and training demands of senior elite female players. Thus,information on female footballers of lower competitive levels and younger age groups was not included.Consequently,an updated review is needed in this area.The present article therefore aims to provide an overview of a series of studies that have been published so far on the specific characteristics of female football players and the demands of match-play.Mean values reported in the literature for age(12—27 years), body height(155—174 cm),body mass(48—72 kg),percent body fat(13%—29%),maximal oxygen uptake(45.1—55.5 m L/kg/m in),Yo-Yo Intermittent Recovery Test Level 1(780—1379 m),maximum heart rate(189—202 bpm),30 m sprint times(4.34—4.96 s),and countermovement jump or vertical jump(28—50 cm)vary mostly according to the players’competitive level and positional role.There are also some special considerations that coaches and other practitioners should be aware of when working w ith female athletes such as the menstrual cycle,potentialpregnancy and lactation,common injury risks(particularly knee and head injuries)and health concerns(e.g.,female athlete triad, iron deficiency,and anem ia)that may affect players’football performance,health or return to play.Reported mean values for total distance covered(4—13 km),distance covered athigh-speed(0.2—1.7 km),average/peak heart rate(74%—87%/94%—99%HRmax),average/peak oxygen uptake(52%—77%/96%—98%VO2max),and blood lactate(2.2—7.3 mmol/L)during women’s footballmatch-play vary according to the players’competitive level and positional role.Methodological differences may account for the discrepancy of the reported values as well.Finally,this review also aims to identify literature gaps that require further scientific research in women’s football and to derive a few practical recommendations.The information presented in this reportprovides an objective pointof reference aboutplayer characteristics and game demands at various levels of women’s football,which can help coaches and sport scientists to design more effective training programs and science-based strategies for the further improvement of players’football performance,health,game standards,and positive image of this sport.

Female soccer players;Match-play requirements;Physical and physiological profi les

1.Introduction

“The future of football is fem inine”,is the famous declaration of Joseph S.Blatter,current Fe´de´ration Internationale de Football Association(FIFA)president,that reflects the rising popularity of the women’s game around the world and highlights the clear objective of FIFA to continue supporting its grow th.1Currently,about 29 m illion women play football, which corresponds to nearly 10%of the totalnumber of male and female footballers worldw ide.2,3The numberof registered female players(at the youth and senior level)grew by over 50%in 2006 compared to the previous FIFA Big Count in 2000.3Additionally,the number of international competitions,professional and recreational leagues for female players of various age groups has considerably increased in recent years. This has given a large number of female footballers the opportunity to train and compete in professional environments, which at the same time has raised the performance expectations placed upon players and increased the need for specific scientific research that could help improve their performance.

Despite the increased popularity and professionalization of women’s football around the world,there is still limited scientific research specific to female players compared to their male counterparts,especially in the areas of players’physical and physiological characteristics and game demands.For instance,in the case of men’s football,there are numerous fulltext peer-reviewed studies that have been published on these topics including players of several nationalities,competitive levels,age groups,and playing positions.Additionally,several comprehensive literature reviews have been published in order to discuss and summarize the findings of a large number of studies in this area.4—12

In women’s football,on the other hand,only one journal review article dealing specifically w ith the applied physiology of female soccer(football)players was found in the present literature review.13This review article was published about 20 years ago,when women’s football was still in its infancy and there were only a few published studies to report on.More recently,a book chapter w ith specific focus in reviewing the game and training demands of senior elite female football players has been published.14However,information on female football players of lower competitive levels and younger age groups was not included.The number of scientific publications specific to player characteristics and game demands in women’s football has noticeably grown since then including information of players of several nationalities,competitive levels,age groups,and playing positions.15—66Consequently, an updated review is needed in this area.

Therefore,the purposes of the present literature review are: 1)to provide an overview of a series of studies thathave been published so far on the specific characteristics of female footballers and the demands of match-play;2)to identify areas/topics that require further scientific research in women’s football;and 3)to derive a few practical recommendations from the information gathered in this review.Know ledge and understanding of this information can help coaches and sport scientists to design more effective training programs and science-based strategies for the further improvement of players’football performance,health,game standards,and positive image of the women’s game.

2.Player characteristics

Several investigations specifi c to female football players of various nationalities,competitive levels,and positional roles have reported on their age,anthropometry,physiological,and physicalattributes(Tables 1 and 2).However,they are stillnot nearly as numerous as in the case of scientific reports on male footballplayers.Furthermore,severalstudies have highlighted the main physical and physiological differences that exists between the genders67—69and a few considerations that are characteristics only of females,and therefore,not present in their male counterparts,such as the menstrual cycle,70—73potential pregnancy and lactation,70,74injury risks,75—79and health concerns.64,72These reports also emphasized how these traits could affect players’football performance,health or their return to play.Hence,coaches of female players should be well educated on these topics.

2.1.Age and anthropometry

The age and body height of elite female football players competing at most recent FIFA Women’s World Cup(Germany 2011)have been recently reported.80The average age for all 16 participating teams was approximately 25 years (range:21—28 years).The average age of the top four most successful teams in this tournament(Japan,USA,Sweden,and France)was in the upper range of 26—28 years.The youngest and oldest players of this tournament were a m idfielder(16 years)and a goalkeeper(38 years),respectively.In agreement w ith other reports on male football players,11female goalkeepers also seem to have longer careers than the field players. Some explanatory reasons for this may include thatexperience plays a crucial role for the goalkeeping position,that goalkeepers are less vulnerable to injuries,and that the game overall physical demands placed upon them are lower compared to those of the field players.8,11In terms of body height values reported from the FIFA Women’s World Cup Germany 2011,80the average heightof all teams was 168 cm. The tallest team was Germany(173 cm)and the shortest Japan (163 cm).The tallest individual player was 187 cm(a central defender)and the shortest 152 cm(a m idfielder).Three of the four sem i-finalists were among the tallest teams in the tournament(USA,Sweden,and France).However,world champion Japan was the shortest team of the tournament. Goalkeepers(mean height 172 cm and range 162—185 cm) were slightly taller than the field players.49

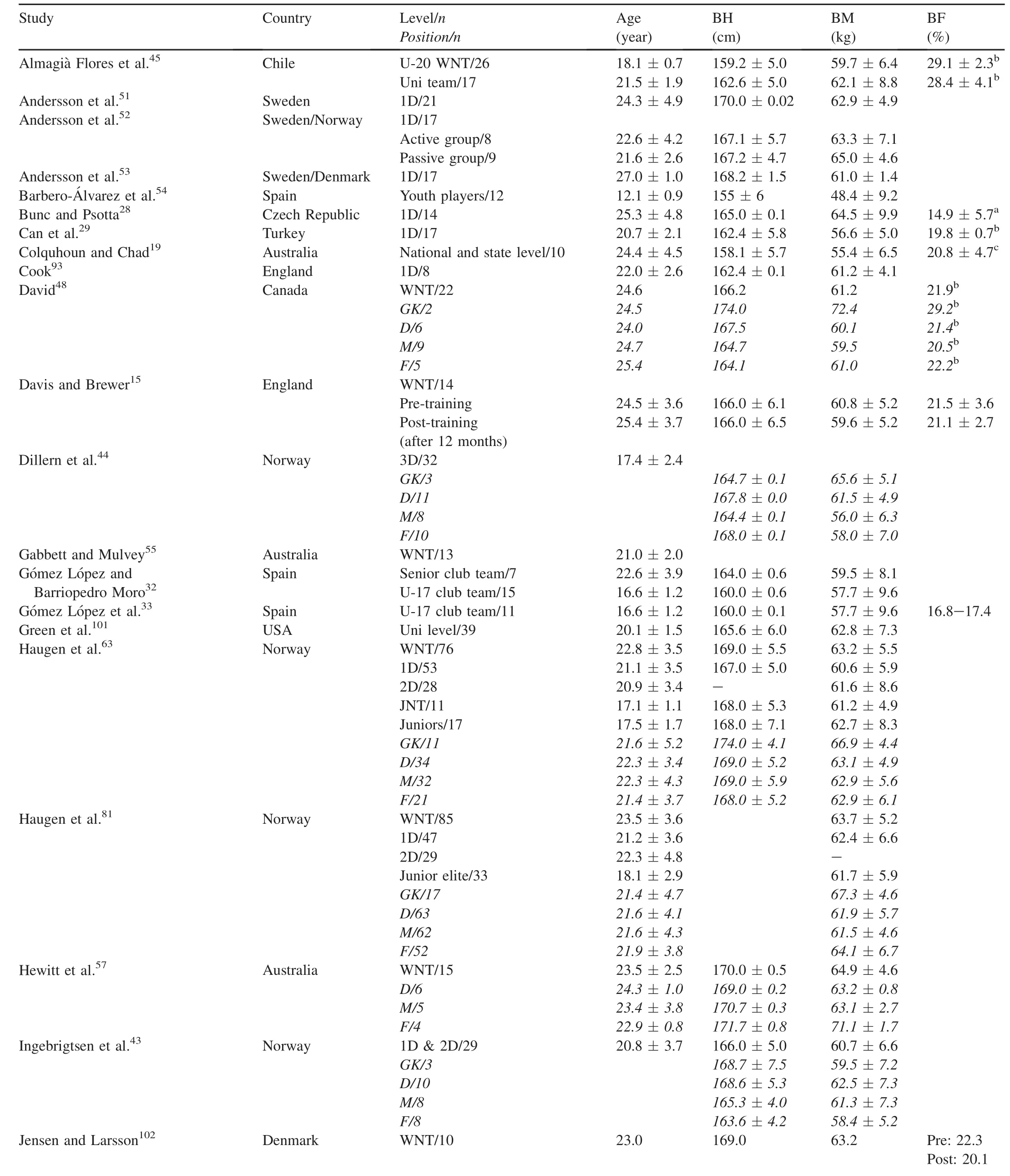

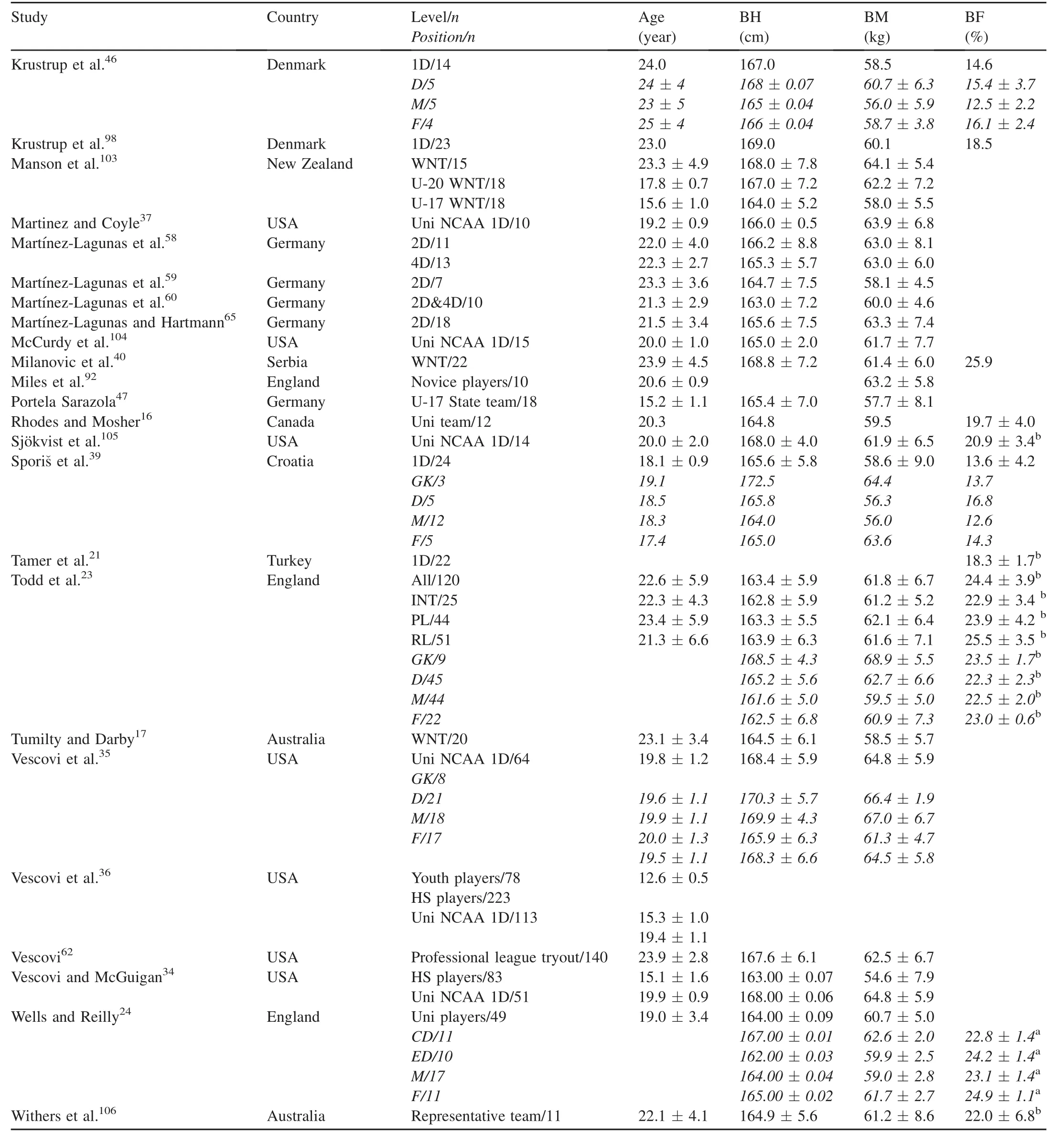

The mean values of age(12—27 years),body height (155—174 cm),body mass(48—72 kg),and percent body fat (13%—29%)reported in other publications for female players vary according to their nationality,competitive level,and positional role(Table 1).In the case of percent body fat,the type of measurement method used may also account for the discrepancies among the reported values.In men’s football,it has been shown that there may be anthropometric predispositions for some positional roles(such as goalkeeping, central defense,and attack),w ith tall players having a certain competitive advantage and,therefore,being selected to play these roles.7A few studies also show that female goalkeepers tend to be taller and heavier than the field players23,35,39,43,48,63,81(Table 1).However,most of these studies have used a general categorization of playing positions (only goalkeepers,defenders,m idfielders,and forwards), Thus,it is still unknown if there are anthropometrical differences among more specific positional roles(e.g.,goalkeepers (GK),central and external defenders(CD,ED),central and external m idfielders(CM,EM),and forwards(F)).Furtherstudies w ith larger sample sizes should investigate to what extent players’anthropometrical characteristics influence role selection in women’s football.

Table 1 Summary of studies reporting on age and anthropometric characteristics of female football players.

Table 1(continued)

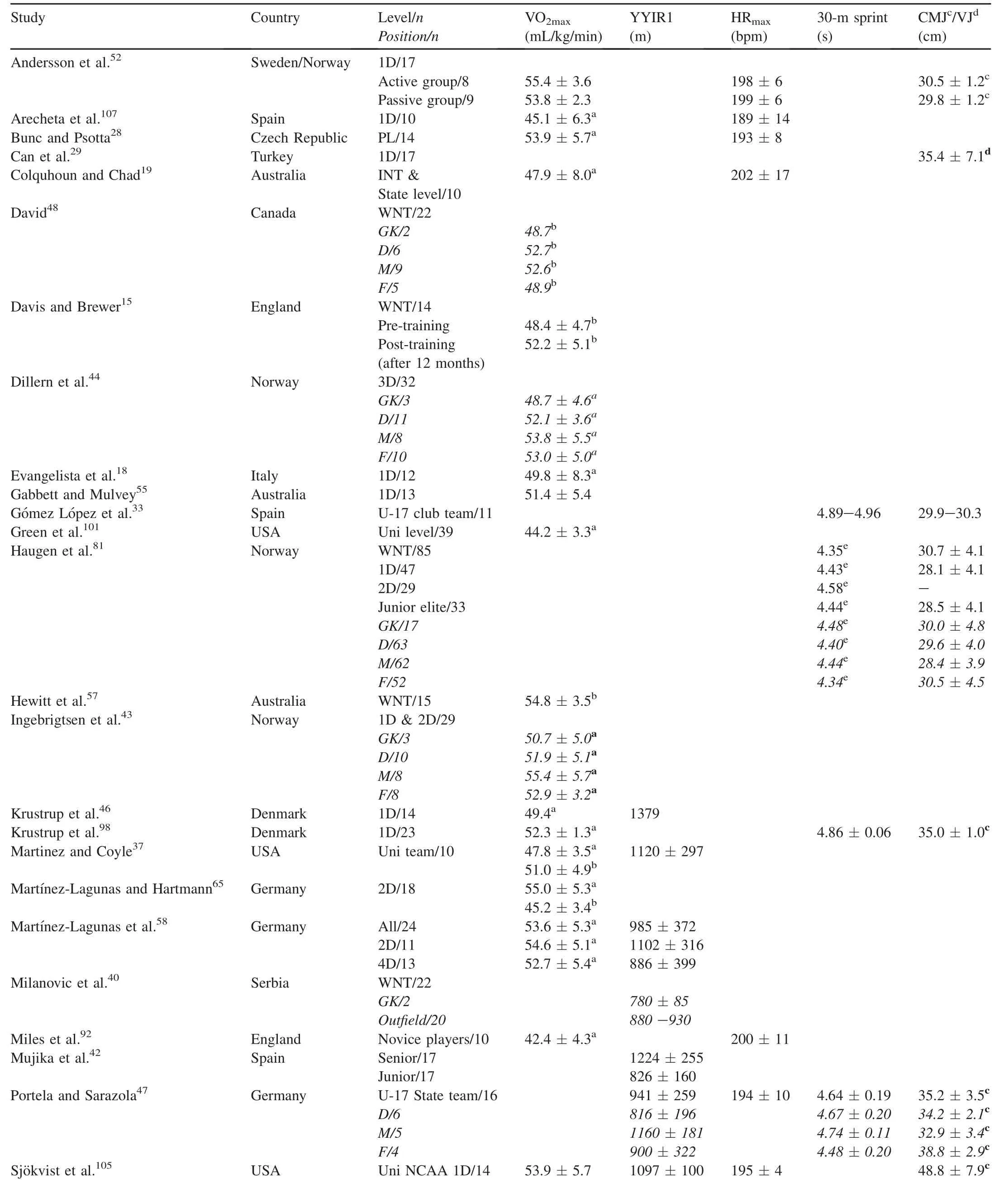

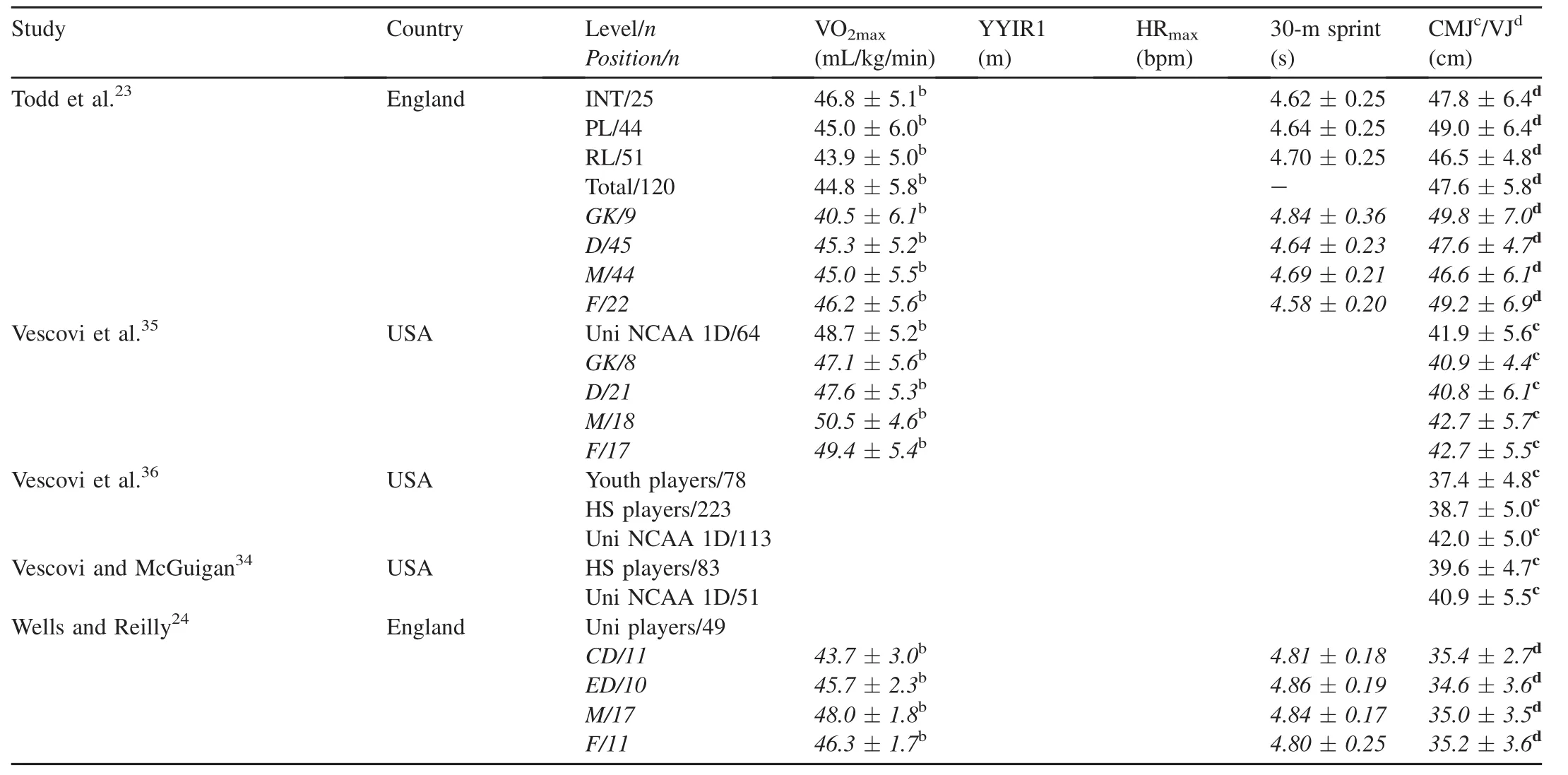

Table 2 Summary of studies reporting on physiological and physical attributes of female football players.

Table 2(continued)

2.2.Physiological and physical attributes

High-levels of physical fi tness provide players w ith the physiological basis to cope w ith the physical demands of the game and allow them to use their technical and tactical abilities effectively,especially towards the end of a match when fatigue starts to arise.82The assessment of players’physical capacities(e.g.,aerobic and anaerobic capacity,speed, strength,and power)may give an indication of the physical demands of a particular level of play because players have to adapt to the requirements of the game in order to be successful at that levelof competition.4,7Moreover,it is believed that the physical demands of the game become more pronounced as the level of competition increases.4Thus,football players independentof their gender need to achieve a reasonable balance in developing these physiological and physical capacities that is appropriate to the level they compete atand their positional role.9

Scientific investigations on the physiological and physical attributes of female footballers have considerably increased in recent years due to the increased popularity of women’s football worldw ide.However,most of the published studies have been focused on adult elite female players of different nationalities,who were competing internationally w ith their respective national team or at the highest women’s football division in their country.Therefore,information about the physiological and physical profi les of adult and youth female players competing at lower levels of the game is still m issing. Furthermore,only a few studies have investigated positional differences specific to the physical condition of female football players.23,24,35,39,40,43,44,47,63The classification of the playing positions used in these studies has been limited to three(defenders,m idfielders,and forwards)or four categories (adding the goalkeepers or the full-backs).However,the physical demands placed in the external and central positions during men’s and women’s match-play are considerably different.83,84Hence,a more detailed classification of playing position including at least six categories(GK,CD,ED,CM, EM,and F)may reveal significant differences in the fi tness profi les of female football players that may be m issed when only a general classification of playing positions is used.This information w ill allow coaches to develop individualized and position-specific physical training programs for their players, which have been proven to be more effective in improvingplayers’physical capacities.85,86Additionally,the evaluation of players’physical performance can assist coaches in several aspects,such as in the identification of individual physical strengths and weaknesses,evaluation of the effectiveness of a specific training program,setting individualand team physical fi tness standards,talent identification and development.9,87

Recent publications have reported on commonly used measures of physiological and physical attributes of female football players of various groups(Table 2).The mean values shown in this table for maximal oxygen uptake(VO2max), performance in Yo-Yo Intermittent Recovery Test Level 1 (YYIR1),maximum heart rate(HRmax),30 m sprint time,and counter-movement jump or vertical jump(CM J/VJ)vary according to the players’nationality,competitive level,and positional role.On average,these players achieved VO2maxvalues that ranged from 45.1 to 55.5 m L/kg/m in,YYIR1 scores of 780—1379 m,HRmaxvalues of 189—202 bpm,30 m sprint times of 4.34—4.96 s,and CMJ/VJ results of 28—50 cm (Table 2).The type of measurement methods used may also account for the discrepancies among the reported values.

2.3.Special considerations

Due to the worldw ide increased popularity and participation numbers in women’s football,many coaches that previously only coached male players are now coaching female players as well.When coaching female players these coaches try to use the same physical training loads they used w ith the men without considering the specific characteristics of female players commonly due to lack of know ledge in this area. Therefore,experienced and novice coaches who are now working in women’s football need to be aware of the main physical and physiological differences that exist between the genders.

These differences start becom ing more significant at the onset of puberty(~12—14 years of age)depending on individual and sex-specific maturation rates.88Before this time period the physical differences between men and women are small and females may have a slight advantage for a short period of time because they usually experience their grow th spurt and sexual maturation on average 2 years earlier than males.88Once males enter into puberty and their testosterone levels start to increase,the gender physical differences lean to their favor.Thus,it is well known that in general females are lighter,shorter,have a lower muscle mass,and more essential sex-specific fat mass than their male counterparts due to inherent biological factors that result in lower absolute physical capacities(e.g.,aerobic endurance,muscular strength, power,speed,and agility)for the average woman compared to the average man.67—69Consequently,coaches and trainers must selectappropriate training loads and intensities based on the actual physical capacities of their female players,especially if they used to work only w ith male athletes before, respecting the principles of training such as progressive overload,adaptation and recovery,specificity,reversibility, and variation.If these recommendations are observed,the relative improvements(percent from maximum)and training adaptations that women get after participating in a welldesigned physical training program could be comparable to those of their male counterparts engaging in a sim ilar regime.67,69

There are also few other considerations that are characteristics of females only that may affect their athletic performance,health or return to sport participation.These include the menstrual cycle,potential pregnancy and lactation,common injury risks,and health concerns.These special considerations w ill be briefl y described next w ith special emphasis on scientific reports specific to female footballers.

In terms of the menstrualcycle,there is scientific consensus that in most cases athletic performance shows little change over the different phases of the cycle,except in the small percentage of women that experience strong pre-menstrual discom fort or painful menses.70Nevertheless,there are scarce scientific reports specific to female football players in this area.Some authors have shown that the injury risk in female football players may be perhaps higher in certain phases of the menstrual cycle than in others.71However,there is still inconsistency in the results of this type of studies,and thus,further research is warranted.The use of contraceptive pills seems to alleviate some pre-menstrual symptoms such as irritability,discom fort,or pain in the breasts and abdomen and to reduce the risk of musculoskeletal injuries,although they may also cause some unwanted side effects.71,89In some cases players who travel,train,and compete regularly ata high-level may also want to delay their menstruation for better com fort and convenience during these activities by using long-acting contraceptive pills.Nonetheless,the long-term consequences on players’health and fertility of such permanent practice are stillunknown,and therefore,it is currently not recommended. Furthermore,menstrual irregularities(i.e.,infrequentor absent menses)in female football players may be linked to excessive energy expenditure due to intensive training combined w ith inadequate nutritional intake,competitive and personal stress, and low body fat,which may result in increased risk of low bone density orosteoporosis,stress fractures due to suppressed estrogen levels,reduced performance,and impaired fertility.72Thus,the absence of menses should not be perceived as a pleasant convenience,especially if the player has already experienced several months of missed periods w ithout being pregnant.This should represent a red flag and the affected player should seek immediate medical help to avoid irreversible damage in her bone health and fertility.

A lthough female athletes may become pregnant at some point during their athletic career,scientific studies on the impact of pregnancy on exercise performance,impact of exercise upon pregnancy and lactation(breastfeeding),training recommendations/guidelines during pregnancy,and recommendations to return to sport after pregnancy for high-level athletes are still scarce.Most of the published literature on these topics refers to the average or sedentary female population70,74but to our know ledge no scientific reports are currently available specific to female football players.Several top level female footballers have successfully returned to compete at the highest level after childbirth.Thus,it will bemeaningful to identify these players and investigate further the strategies they have used to succeed in this task.The information that can be gathered in this type of study w ill be very useful for other female players interested in combining their football career w ith establishing a family and having kids.

It is also well known that female football players have a higher risk to suffer from knee(e.g.,anterior cruciate ligament (ACL)tear)75and head injuries(e.g.,concussion)76than their male counterparts.Consequently,coaches and players should be well informed about the potential risks factors and prevention programs or recommendations thathave been recently developed to reduce the incidence of these severe injuries.77—79Finally,health problems such as the female athlete triad(syndrome that includes three interrelated elements:low energy availability/eating disorders,menstrual dysfunction,and low body density/osteoporosis),72iron deficiency,and anem ia64may also be common among female footballplayers.These diseases can have severe consequences on the health,well-being,and athletic performance of the affected players.Therefore,more scientific research should be performed in order to develop specific strategies/recommendations to prevent,recognize,and treat these health issues among female footballers.

3.Demands of the gam e

Published reports on the physical and physiological demands ofwomen’s footballare more limited than the available literature on female players’characteristics and by far scarcer than the related research specific to men’s football.However, due to the increased popularity of the women’s game,several investigations have been conducted recently in this area.These new studies provide significant information for better understanding the demands of the women’s football game.

3.1.Physical demands

Football is a sport of intermittent nature that requires multiple and constant changes of direction running intensity, accelerations,and types of movements(running forwards, backwards,lateral movements,jumps,tackles,etc.).The specificity of training principle in sports science states that the most effective training is the one that resembles the demands of a sport/game as close as possible.Therefore,a broad understanding of the physical demands of women’s football is essential for developing sport-specific conditioning programs for female football players.

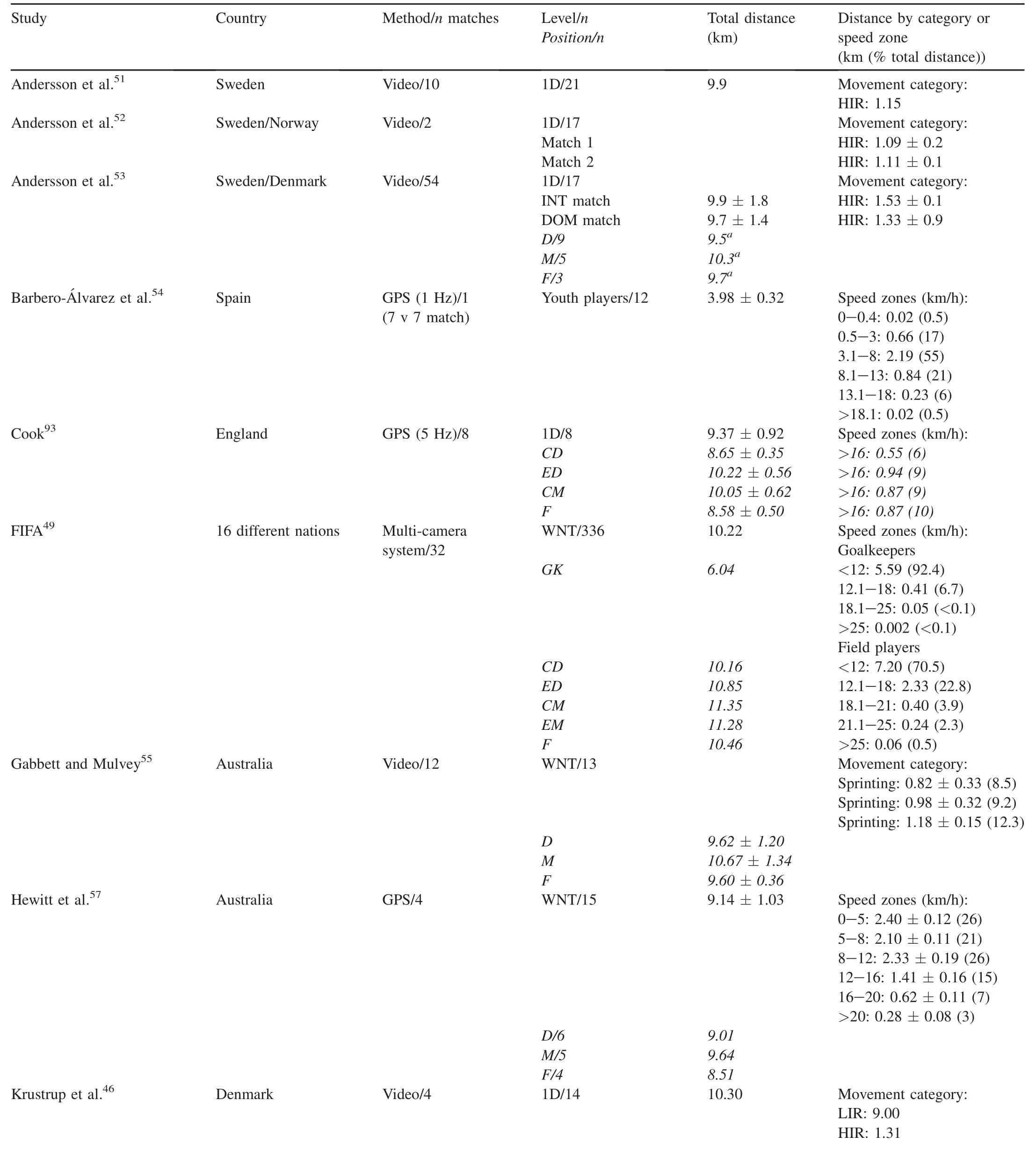

Recent technological advances(e.g.,computerized videobased time-motion analysis systems,sem i-automatic multicamera systems,and Global Positioning System(GPS))now allow the simultaneous evaluation of the physical demands placed upon several or all players participating in a football match and can be completed in a relatively short period of time.90The pioneer work in this area started in the late 1970’s in men’s footballw ith manualvideo-based notationalanalysis such as the one used in the classical study of Reilly and Thomas.91This latter method was very labor intensive,time consum ing and restricted the analysis to a single player at a time.Since then many investigations employing a variety of measurement methods have been conducted relative to this topic in men’s football and excellent reviews5,6,11,12have summarized their findings.In women’s football,the oldest reports date back to the early 1990’s.13,92More recent investigations are now available and summarized in Table 3, including the pioneer reports on the topic as well.13,92The mean values shown in this table for total distance covered (4—13 km)and distance covered at different speeds(e.g., 0.2—1.7 km covered at high speeds)vary according to the players’nationality,competitive level,positional role,and method of measurement employed in each study.This information provides a good pointof reference for players,coaches, and sport scientists regarding the overall physical demands of women’s football match-play.

Overall,the studies mentioned above showed thatmale and female players cover sim ilar total distances during a football match compared to their male counterparts.However,the main difference lies in the amount of distance covered at highspeeds(>15 km/h).14,51Male players typically cover significantly more distance at these speeds than female players mainly due to the inherent biological differences between the genders(e.g.,in anthropometry and physical capacities).The amount of distance covered at high-speeds also seems to be quite sensitive to differentiate players of various competition levels both in men’s and women’s football.Players of higher competition levels usually cover a larger distance at these speeds than players competing at lower levels.53,55,61A few of these studies also revealed significantdifferences according to the players’positional role53,61,93and evidence of decreased players’physical performance either in terms of total distance covered or amountof high-intensity running in the second half compared to the fi rst half of match-play,which may be the result of fatigue.46,49,51,53,59,60,93

The physical analysis of the 2011 FIFA Women’s World in Germany49investigated all 32 matches disputed among 16 participating teams,including over 300 players and over 700 data sets.A ll measurements were made through a sem iautomatic multi-camera system that allowed the simultaneous analysis of all players participating in each match.This report provides to date the largest international database about the physical demands ofwomen’s footballmatches disputed at the highest levelof the game among 16 differentnations from all continents.Additionally,italso includes some practical training recommendations based on the study findings.The average total duration of these World Cup matches(notincluding extra time) was 92—95 min,whereas the average actual playing time was only about57.5 m in(61%—63%of totalmatch duration).Field players covered on average a total distance of 10.2 km,w ith 0.5%ofmaximum sprints(>25 km/h),2.3%ofoptimum sprints (21.1—25 km/h),3.9%of high-speed runs(18.1—21 km/h), 22.8%of moderate runs(12.1—18 km/h),and 70.5%of lowspeed runs(<12 km/h).In contrast,goalkeepers covered a totalaverage distance of 6 km,w ith 0.6%—0.7%of maximum and optimum sprints,<1%of high-speed runs,5%—6%of moderate runs,and 91%—92%of low-speed runs.This reportalso revealed positionaldifferencesamong the field players(i.e., tendency of the centraland externalm idfielders to cover larger total distances,the externalm idfielders the largest distance in high-speed runs,and the forwards the larger distance in maximal and optimal sprints compared to the other field players).Overall,there was an average 2.7%decrease in total distancecovered by the field playersin the 2nd half compared to the1sthalfofmatch-play.Theteamsmaking itto thesem i-finals (USA,Japan,Sweden,and France)also showed someof the best physical performances during the tournament.However,there were also othervery fi tteams thatwere knocked-outearly from the tournament,which highlights the fact thata high physical capacity is not the only requirement to succeed in women’s football.Other factors such as the technical,tactical,mental/ psychological characteristicsof the participating players/teams also play a crucial role.Nonetheless,a high-levelof fi tness does provide a competitive advantage by helping players to maintain high-intensity exercise longer and being more resistant to fatigue,especially towards the end of a game.46,51

Table 3 Summary of studies reporting on physical demands of women’s football.

Table 3(continued)

Future studies should provide a more detailed analysis of accelerations,changes of direction,and other types of movements required during a women’s football match because this information is stillscarce.So far the main focus of the current published reports has been in total distance and distance covered at various running speeds.Further investigations of the physical game demands place upon other players’age groups and competition levels should be conducted in the future(e.g.,comparison of U17,U20 and senior internationalvs.national competitions).A longitudinal study comparing the physical demands of women’s football match-play at internationaland national competitions over severalyears may also provide meaningful information about the evolution of the women’s game over time.Detailed classifications of playing positions(including detailed analysis of the goalkeeper position),fatigue development analysis during and after matchplay and simultaneous analysis of physical,technical,and tactical game demands should also be considered in future research in this area.

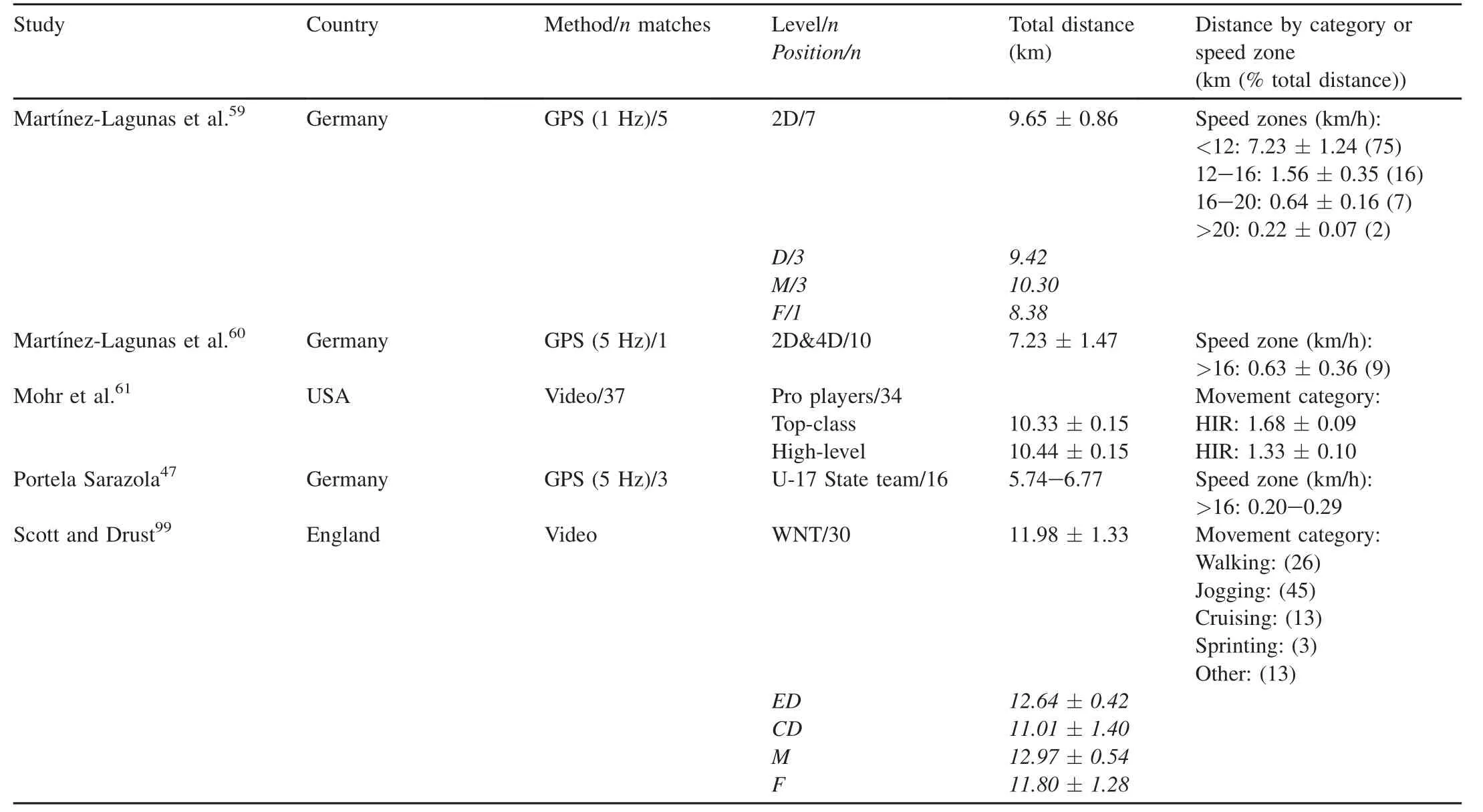

3.2.Physiological demands

Investigations on the physiological demands of women’s football match-play involving simultaneous measurements of heart rate(HR),oxygen consumption(VO2),and blood lactate (La)are still scarce(Table 4)mainly due to the difficulty,high cost,and laborious procedures required to conduct this type of studies.Even in the case of men’s football,they are also lim ited.To our know ledge,there is to date only one published study that has included simultaneous HR,VO2,La,and GPS measurements during a women’s football match.60This investigation consisted of a full 90 min competitive friendly match(11vs.11),in which continuous HR and VO2(viaportable spirometry)and La assessment(every 15 m in)was conducted simultaneously on 10 outfield players during the duration of the match(Fig.1).Similar to other authors,46,59,94Martı´nez-Lagunas et al.60found a significant reduction in the players’physical and physiological performance in the 2nd compared to the 1st half and a large individual variability of the results(mostly due to the players’positional role).However,the results of this latter study(Table 4) are lower than published data on VO2average values reported for male footballers collected via portable spirometry(57%—77%VO2max)94,95or by using Douglas bags (47%—60%VO2max)96during friendly games;average La values(2.4—10.0 mmol/L)6,97reported formale players during match-play; average HR (81%—87% HRmax),46,53,59La(2.7—5.1 mmol/L),22,98and GPS(e.g.,9.1—9.6 km of total distance covered)57,59or computerized video-based (10.2—12.0 km of total distance covered)46,49,53,55,61,99physical data of female football players during competitive matches.The HR and VO2results from Martı´nez-Lagunas etal.60are also lower than the average reported values based on indirect estimation via the HR-VO2relationship(approximately 80%—90%of HRmaxcorresponding to~70%—77% VO2max), which may tend to overestimate actual VO2.46,53,97,100Possible reasons for the discrepancy of results may include gender,players’characteristics and competitive level,game conditions,methodological differences,and movement impairment due to the measuring equipment. Further studies using a larger sample size(players and games) should be conducted in order to verify these results.Moreover, competitive leveland positional role differencesshould also be evaluated in more detail in the future.

Table 4Summary of studies reporting on physiological demands of women’s football.

4.Conclusions,future directions,and practical recomm endations

The present literature review aimed 1)to provide an overview of a series of studies thathave been published so far on the specific characteristics of female footballers and the demands of match-play;2)to identify areas/topics that require furtherscientific research in women’s football;and 3)to derive a few practical recommendations from the information gathered in this review.Published studies on the specific characteristics of female football players have reported the follow ing mean values for age (12—27 years), body height (155—174 cm),body mass(48—72 kg),percent body fat (13%—29%),VO2max(45.1—55.5 m L/kg/m in),YYIR1 (780—1379 m),HRmax(189—202 bpm),30 m sprint times (4.34—4.96 s),and counter-movement jump or vertical jump (28—50 cm)that vary mainly according to the players’competitive level and positional role.There are also some special considerations that coaches and other practitioners should be aware of when working w ith female athletes such as the menstrual cycle,potential pregnancy and lactation,common injury risks(particularly knee and head injuries)and health concerns(e.g.,female athlete triad,iron deficiency,and anem ia)that may affect players’football performance,healthor return to play.In terms of the demands of the game,reported mean values for total distance covered(4—13 km), distance covered at high-speed(0.2—1.7 km),average/peak HR (74%—87%/94%—99% HRmax),average/peak VO2(52%—77%/96%—98%VO2max),and La(2.2—7.3 mmol/L) during women’s footballmatch-play also vary according to the players’competitive leveland positional role.Methodological differences may account for the discrepancy of the reported values as well.

Fig.1.Portable spirometry measurements during a women’s football match.

Due to the increased popularity and participation numbers of women’s football worldw ide,there is a high demand of scientific research specific to female players of various age groups,nationalities,competitive levels,and positional roles (including detailed analysis of the goalkeeping demands and more specifi c field player classifications).To date,most investigations in the areas of player characteristics and demands of the game are of a descriptive nature.Therefore, there is a need for more experimental studies that evaluate the effectiveness of certain training and recovery interventions(e.g.,1vs.2 competitive matches per week)on players’characteristics(e.g.,anthropometry,physiological, and physical capacities)and on their football performance during match-play.The latter is notonly in terms of physical/ physiological aspects but also regarding technical,tactical, and mental/psychological elements because football performance is influenced by all these factors,and thus,all should be taken into account.There is also considerable scope for further research specific to female players in topics such as the effects of the menstrual cycle and contraceptive pills use, potential pregnancy and lactation,common injury risks (particularly knee and head injuries),and health concerns (e.g.,female athlete triad,iron deficiency,and anem ia)on footballperformance and return to play.Finally,more studies are needed to quantify the physiological demands placed upon female footballers during match-play and training sessions in terms of on-field VO2, HR, and La concentrations.

Practical recommendations that can be derived from the present review include:

·The physical capacities of players should be tested regularly through objective and standardized performance assessment in order to identify their strengths and weaknesses.This can also be useful for evaluating the effectiveness of a specific training program,setting individual and team fi tness standards,and talent identification/ development.

·Based on this information physical training should be individualized according to the players’current fi tness levels,positional role,and level of competition.This w ill help players to cope more efficiently w ith the demands of the game.

·Coaches and practitioners working with female players should be aware of their specific characteristics and understand gender differences especially if they used to work only w ith male athletes before.An open approach and know ledge on menstruation and pregnancy including their potential impact on football performance is needed.

·The long-term consequences of using long-acting contraceptive pills to manipulate the players’menstrual cycle according to their competition and training schedules are still unknown,and therefore,this practice is currently not recommended.

·Due to the higher risk of female players to suffer from knee and head injuries compared to their male counterparts,coaches should implement an injury prevention program for their female players on a regular basis(e.g., FIFA 11+injury prevention program).

·Health problems such as the female athlete triad(low energy availability/eating disorders,menstrual dysfunction,and low body density/osteoporosis),iron deficiency, and anem ia may affect some female footballers.Thus, coaches should be know ledgeable about their common symptoms and consequences in order to identify the affected players early and refer them as soon as possible to a physician.

·Coaches and practitioners working w ith female players should be educated on the topics mentioned above through women’s football specific courses.

·The information presented in this report provides an objective point of reference about player characteristics and game demands at various levels of women’s football, which can help coaches and sportscientists to design more effective training programs and science-based strategies for the further improvement of players’football performance,health,game standards,and positive image of this sport.

Acknow ledgment

The authors would like to thank Matthew Barr for his assistance in proofreading the present manuscript.

1.FIFA.Women’s football:developing the game.Zurich:FIFA;2012. p.287.

2.FIFA.Women’s football;2012.Available at:http://www.fi fa.com/mm/ document/footballdevelopment/women/01/59/58/21/w f_backgroundpaper_ 200112.pdf;[accessed 03.02.2014].

3.FIFA.FIFA big count 2006;2007.Available at:http://www.fi fa. com/mm/document/fi fafacts/bcoffsurv/bigcount.statspackage_7024. pdf;[accessed 03.02.2014].

4.Reilly T.Physiological profi le of the player.In:Ekblom B,editor.Handbook of sports medicine and science:football(soccer).Oxford, United Kingdom:Blackwell Scientifi c Publications;1994.p.78—94.

5.Ekblom B.Applied physiology of soccer.Sports Med1986;3:50—60.

6.Stølen T,Chamari K,Castagna C,W isløff U.Physiology of soccer:an update.Sports Med2005;35:501—36.

7.Reilly T,Bangsbo J,Franks A.Anthropometric and physiological predispositions for elite soccer.J Sports Sci2000;18:669—83.

8.Reilly T.Physiological aspects of soccer.Biol Sport1994;11:3—20.

9.Svensson M,Drust B.Testing soccer players.JSportsSci2005;23:601—18.

10.Tum ilty D.Physiological characteristics of elite soccer players.Sports Med1993;16:80—96.

11.Shephard RJ.Biology and medicine of soccer:an update.J Sports Sci1999;17:757—86.

12.Bangsbo J,Mohr M,Krustrup P.Physical and metabolic demands of training and match-play in the elite football player.J Sports Sci2006;24:665—74.

13.Davis JA,Brewer J.Applied physiology of female soccer players.Sports Med1993;16:180—9.

14.Scott D,Andersson H.Women’s soccer.In:Williams MA,editor.Science and soccer:developing elite performers.Oxon:Routledge;2013. p.237—58.

15.Davis JA,Brewer J.Physiological characteristics of an international female soccer squad.J Sports Sci1992;10:142—3.

16.Rhodes EC,Mosher RE.Aerobic and anaerobic characteristics of elite female university soccer players.J Sports Sci1992;10:143—4.

17.Tum ilty D,Darby S.Physiological characteristics of Australian female soccer players.J Sports Sci1992;10:145.

18.Evangelista M,Pandolfi O,Fanton F,Faina M.A functional model of female soccer players:analysis of functional characteristics.J Sports Sci1992;10:165.

19.Colquhoun D,Chad KE.Physiological characteristics of Australian female soccer players after a competitive season.Aust J Sci Med Sport1986;18:9—12.

20.Jensen K,Larsson B.Variations in physical capacity in a period including supplemental training of the national Danish soccer team for women.In:Reilly T,Clarys J,Stibbe A,editors.Science and football II: proceedings of the Second World Congress on Science and Football. Abingdon,OX:Taylor&Francis Group;1993.p.114—7.

21.Tamer K,Gunay M,Tiryaki G,Cicioolu I,Erol E.Physiological characteristics of Turkish female soccer players.In:Reilly T,Bangsbo J, Hughes MD,editors.Science and football III:proceedings of the third world congress on science and football.Abingdon,OX:Taylor&Francis Group;1997.p.37—9.

22.Weber K,Gerisch G,Bisanz G.Wettkampf und training im Frauenfußball unter leistungsphysiologischen Gesichtspunkten(Competition and training in women’s soccer under a physiological point of view).In: Ba¨um ler G,Bauer G,editors.Sportwissenschaft rund um den Fußball (Sports science specific to soccer),vol.96.Hamburg:Czwalina Verlag; 1998.p.87—102.

23.Todd MK,ScottD,Chisnall PJ.Fitness characteristics of English female soccer players:an analysis by position and playing standard.In: Spinks W,editor.Science and football IV.London:Routledge;2002. p.374—81.

24.Wells C,Reilly T.Influence of playing position on fi tness and performance measures in female soccer players.In:Spinks W,editor.Science and football IV.London:Routledge;2002.p.369—73.

25.Dowson MN,Cronin JB,Presland JD.Anthropometric and physiological differences between gender and age groups of New Zealand national soccer players.In:Spinks W,editor.Science and football IV.London: Routledge;2002.p.63—71.

26.Helgerud J,Hoff J,Wisloff U.Gender differences in strength and endurance of elite soccer players.In:Spinks W,editor.Science and football IV.London:Routledge;2002.p.382—3.

27.Luhtanen P,Vanttinen T,Hayrinen M,Brown EW.A comparison of selected physical,skilland game understanding abilities in Finnish youth soccer players.In:Spinks W,editor.Science and football IV.London: Routledge;2002.p.271—4.

28.Bunc V,Psotta R.Functionalcharacteristics of elite Czech female soccer players.J Sports Sci2004;22:528.

29.Can F,Yilmaz I,Erden Z.Morphological characteristics and performance variables of women soccer players.J Strength Cond Res2004;18:480—5.

30.Polman R,Walsh D,Bloom field J,Nesti M.Effective conditioning of female soccer players.J Sports Sci2004;22:191—203.

31.Kirkendall DT,Leonard K,Garrett JWE.On the relationship of fi tness to running volume and intensity in female soccer players.In:Reilly T,Cabri J, Arau´jo D,editors.Science and footballV:the proceedings of the Fifth World Congresson Science and Football.Abigdon,OX:Routledge;2005.p.395—8.

32.Go´mez Lo´pez M,Barriopedro Moro M.Caracterı´sticas fisiolo´gicas de jugadoras espan˜olas de fu´tbol femenino(Physiological characteristics of Spanish female soccer players).Kronos2005;4:26—32.

33.Go´mez Lo´pez M,Barriopedro Moro M,Pagola A ldazabal I.Evolucio´n de la condicio´n fı´sica de las jugadoras de fu´tbol del atle´tico fe´m inas B durante la temporada(Evolution of the physical condition of female soccer players of atle´tico fe´m inas B during a competitive season).Revista Digital(Digital Magazine)2006;10(93)http://www.efdeportes. com/efd93/fem inas.htm.

34.Vescovi JD,M cGuigan MR.Relationships between sprinting,agility,and jump ability in female athletes.J Sports Sci2008;26:97—107.

35.Vescovi JD,Brown TD,Murray TM.Positional characteristics of physical performance in division I college female soccer players.J Sports Med Phys Fitness2006;46:221—6.

36.Vescovi JD,Rupf R,Brown TD,Marques MC.Physical performance characteristics of high-level female soccer players 12—21 years of age.Scand J Med Sci Sports2011;21:670—8.

37.Martinez V,Coyle EF.Validity of the“beep test”in estimating VO2maxamong female college soccerplayers.Med SciSports Exerc2006;38:509.

38.M iller TA,Thierry-Aguilera R,Congleton JJ,Amendola AA,Clark MJ, Crouse SF,et al.Seasonal changes in VO2maxamong division 1a collegiate women soccer players.J Strength Cond Res2007;21:48—51.

39.Sporiˇs G,ˇCanaki M,Bariˇsiˇc V.Morphological differences of elite Croatian female soccer players according to team position.Croat Sports Med J2007;22:91—6.

40.M ilanovic Z,Sporis G,Trajkovic N.Differences in body composite and physicalmatch performance in female soccer players according to team position.J Hum Sport Exerc2012;7:S67—72.

41.Sporiˇs G,Jovanovic M,Krakan I,Fiorentini F.Effects of strength training on aerobic and anaerobic power in female soccer players.Sport Sci2011;4:32—7.

42.Mujika I,Santisteban J,Impellizzeri FM,Castagna C.Fitness determ inants of success in men’s and women’s football.J Sports Sci2009;27:107—14.

43.Ingebrigtsen J,Dillern T,Shalfawi SAI.Aerobic capacities and athropometric characteristics of elite female soccer players.J Strength Cond Res2011;25:3352—7.

44.Dillern T,Ingebrigtsen J,Shalfaw i SAI.Aerobic capacity and anthropometric characteristics of elite-recruit female soccer players.Serb J Sports Sci2012;6:43—9.

45.A lmagia`Flores AA,Rodrı´guez Rodrı´guez F,Barraza Go´mez FO,Lizana Arce PJ,Jorquera Aguilera CA.Perfi l antropome´trico de jugadoras chilenas de fu´tbol femenino(Anthropometric profi le of female football—soccer chilean players).Int J Morphol2008;26:817—21.

46.Krustrup P,Mohr M,Ellingsgaard H,Bangsbo J.Physical demands during an elite female soccer game:importance of training status.Med Sci Sports Exerc2005;37:1242—8.

47.Portela Sarazola J.Deskription und exemplarische Analyse der Laufleistung im Spiel und einer ausgewa¨hlten Testbaterie bei jugendlichen Fußballerinnen(Description and exemplary analysis of match running performance and a selected battery of tests in adolescent female soccer players).Leipzig:Institut fu¨r Bewegungs-und Trainingsw issenschaftder Sportarten II(Institute of Movement and Training Science),Universita¨t Leipzig(University of Leipzig);2012[Master Thesis].

48.David TA.A physiological profi le of the 1999 Canadian women’s soccer team.Schoolof PhysicalEducation,University of Victoria;2003[Master Thesis].

49.FIFA.Physical analysis of the FIFA women’s world cup Germany 2011&trade.In:Ritschard M,Tschopp M,editors.Aesch/ZH. Sw itzerland:FIFA Technical Study Group;2012.

50.Rosenbloom CA,Loucks AB,Ekblom B.Special populations:the female player and the youth player.J Sports Sci2006;24:783—93.

51.Andersson H,Ekblom B,Krustrup P.Elite football on artifi cial turf versus naturalgrass:movementpatterns,technical standards,and player impressions.J Sports Sci2008;26:113—22.

52.Andersson H,Raastad T,Nilsson J,Paulsen G,Garthe I,Kadi F. Neuromuscular fatigue and recovery in elite female soccer:effects of active recovery.Med Sci Sports Exerc2008;40:372—80.

53.Andersson HA˜,Randers MB,Heiner-Møller A,Krustrup P,Mohr M. Elite female soccer players perform more high-intensity running when playing in international games compared w ith domestic league games.J Strength Cond Res2010;24:912—9.

54.Barbero-A´lvarez JC,Barbero-A´lvarez V,Go´mez M,Castagna C.Ana´-lisis cinema´tico del perfi l de actividad en jugadoras infantiles de fu´tbol mediante tecnologı´a GPS(Kinematic analysis of activity profi le in under 15 players w ith GPS technology).Kronos2009;8:35—42.

55.Gabbett TJ,Mulvey MJ.Time-motion analysis of small-sided training games and competition in elite women soccer players.J Strength Cond Res2008;22:543—52.

56.Gabbett TJ,Wiig H,Spencer M.Repeated high-intensity running and sprinting in elite women’s soccer competition.Int J Sports Physiol Perform2013;8:130—8.

57.Hewitt A,Whiters R,Lyons K.Match analyses of Australian international female soccer players using an athletic tracking device.In: Reilly T,Korkusuz F,editors.Proceedings of the sixth world congress on science and football.Antalya,Turkey:Routledge;2009.p.224—8.

58.Martı´nez-Lagunas V,Go¨tz JK,Niessen M,Hermsdorf M,Hartmann U.Aerobic characteristics of german female soccer players of two different competitive levels.Final program of the 60th Annual Meeting of the American College of Sports Medicine.Indianapolis.USA:ACSM;2013. p.139.

59.Martı´nez-Lagunas V,Niessen M,Hartmann U.Physical match performance analysis of German female football players using GPS technology.In:Korkusuz F,Ertan H,Tsolakidis E,editors.Book of abstracts of the 15th Annual Congress of the European College of Sport Science. Antalya,Turkey:ECSS;2010.p.501—2.

60.Martı´nez-Lagunas V,Niessen M,Hartmann U.Physiological and physical demands of a women’s football match.In:Balague N,Torrents C, Vilanova A,Cadefau J,Tarrago R,Tsolakidis E,editors.Proceedings of the 18th Annual Congress of the European College of Sport Science. Barcelona,Spain:ECSS;2013.p.688.

61.Mohr M,Krustrup P,Andersson H,Kirkendal D,Bangsbo J.Match activities of elite women soccer players at different performance levels.J Strength Cond Res2008;22:341—9.

62.Vescovi JD.Sprint speed characteristics of high-level American female soccer players:female athletes in motion(faim)study.J Sci Med Sport/ Sports Med Austral2012;15:474—8.

63.Haugen TA,Tønnessen E,Hem E,Leirstein S,Seiler S.VO2maxcharacteristics of elite female soccer players 1989—2007.Int J Sports Physiol Perform2014;9:515—21.

64.Landahl G,Adolfsson P,Borjesson M,Mannheimer C,Rodjer S.Iron deficiency and anemia:a common problem in female elite soccer players.Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab2005;15:689—94.

65.Martı´nez-Lagunas V,Hartmann U.Validity of the Yo-Yo intermittent recovery test level 1 for direct measurement or indirect estimation of maximal oxygen uptake among female soccer players.Int J Sports Physiol Perform2014;9:825—31.

66.La Torre A,Vernillo G,Rodigari A,Maggioni M,Merati G.Explosive strength in female 11-on-11 versus 7-on-7 soccer players.Sport Sci Health2007;2:80—4.

67.Shephard RJ.Exercise and training in women,part I:infl uence of gender on exercise and training responses.Can J Appl Physiol2000;25:19.

68.Kirkendall DT.Issues in training the female player.Br J Sports Med2007;41:i64—7.

69.Lew is DA,Kamon E,Hodgson JL.Physiological differences between genders. Implications for sports conditioning.SportsMed1986;3:357—69.

70.Shephard RJ.Exercises and training in women,part II:influence of menstrual cycle and pregnancy on exercise responses.Can J Appl Physiol2000;25:35.

71.Moller-Nielsen J,Hammar M.Women’s soccer injuries in relation to the menstrual cycle and oral contraceptive use.Med Sci Sports Exerc1989;21:126—9.

72.Sundgot-Borgen J,Klungland Torstveit M.The female football player, disordered eating,menstrual function and bone health.Br J Sports Med2007;41:i68—72.

73.Lebrun CM,M cKenzie DC,Prior JC,Taunton JE.Effects of menstrual cycle phase on athletic performance.MedSci SportsExerc1995;27:437—44.

74.Artal R,O’Toole M.Guidelines of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists for exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period.Br J Sports Med2003;37:6—12.

75.Yu B,Garrett WE.Mechanisms of non-contact acl injuries.Br J Sports Med2007;41:i47—51.

76.Dvorak J,M cCrory P,Kirkendall DT.Head injuries in the female football player:incidence,mechanisms,risk factors and management.Br J Sports Med2007;41:i44—6.

77.Silvers HJ,Mandelbaum BR.Prevention of anterior cruciate ligament injury in the female athlete.Br J Sports Med2007;41:i52—9.

78.Soligard T,M yklebust G,Steffen K,Holme I,Silvers H,Bizzini M, et al.Comprehensive warm-up programme to prevent injuries in young female footballers:cluster random ised controlled trial.BMJ2008;337:a2469.

79.Kirkendall DT,Jordan SE,Garrett WE.Heading and head injuries in soccer.Sports Med2001;31:369—86.

80.FIFA.FIFA Women’s World Cup 2011:technical report and statistics. A ltsta¨tten,Switzerland:FIFA;2011.

81.Haugen TA,Tønnessen E,Seiler S.Speed and countermovement-jump characteristics of elite female soccer players,1995—2010.Int J Sports Physiol Perform2012;7:340—9.

82.Bangsbo J.The physiology of soccer—with special reference to intense intermittent exercise.Copenhagen,Denmark:August Krogh Institute, University of Copenhagen;1993[Dissertation].

83.Di Salvo V,Baron R,Tschan H,Calderon Montero FJ,Bachl N, Pigozzi F.Performance characteristics according to playing position in elite soccer.Int J Sports Med2007;28:222—7.

84.Ritchard M,Tschopp M,editors.Physical analysis of the FIFAWomen’s World Cup Germany 2011&trade.Zurich:FIFA;2012.

85.DiSalvo V,PigozziF.Physical training of footballplayers based on their positional rules in the team:effects on performance-related factors.J Sports Med Phys Fitness1998;38:294—7.

86.Rhea MR,Lavinge DM,Robbins P,Esteve-Lanao J,Hultgren TL. Metabolic conditioning among soccer players.J Strength Cond Res2009;23:800—6.

87.Balsom P.Evaluation of physical performance.In:Ekblom B,editor.Handbook of sports medicine and science:football(soccer).Oxford, UK:Blackwell Scientifi c Publications;1994.p.102—23.

88.Bangsbo J.Aerobic and anaerobic training in soccer—with special emphasis on training of youth players.Copenhagen:August Krogh Institute,University of Copenhagen;2007.

89.Lebrun CM.Effectof the differentphasesof the menstrualcycle and oral contraceptives on athletic performance.Sports Med1993;16:400—30.

90.Carling C,Bloom field J,Nelsen L,Reilly T.The role of motion analysis in elite soccer:contemporary performance measurement techniques and work rate data.Sports Med2008;38:839—62.

91.Reilly T,Thomas V.Motion analysis of work-rate in different positional roles in professional football match-play.JHumMoveStud1976;2:87—97.

92.M iles A,Maclaren D,Reilly T,Yamanaka K.An analysis of physiological strain in four-a-side women’s soccer.In:Reilly T,editor.Science and football II.London:E&FN Spon;1993.p.140—5.

93.Cook JL.Analysis of positionalwork rate demands in semielite female soccer match play.Abstract presented at international convention on Science.Glasgow,UK:Education and Medicine in Sport(ICSEM IS); July 19—24,2012.

94.Ferrauti A,Giesen HT,Merheim G,Weber K.Indirekte kalorimetrie im Fussballspiel(Indirect calorimetry in a soccer game).Dtsch Z Sportmed(German J Sports Med)2006;57:142—6.

95.Gatterer H.Sauerstoffaufnahme wa¨hrend eines Fussballspiels:Eine Fallbeschreibung(Oxygen uptake during soccer:a case report).Dtsch Z Sportmed(German J Sports Med)2007;58:83—5.

96.Ogushi T,Ohashi J,Nagahama H,Isokawa M,Suzuki S.Work intensity during soccer match-play(a case study).In:Reilly T,Clarys J,Stibbe A, editors.Proceedings of the Second World Congress on Science and Football.Eindhoven:Taylor&Francis Group;1993.p.121—3.

97.Bangsbo J.Energy demands in competitive soccer.J Sports Sci1994;12:S5—12.

98.Krustrup P,Zebis M,Jensen JM,Mohr M.Game-induced fatigue patterns in elite female soccer.J Strength Cond Res2010;24:437—41.

99.Scott D,Drust B.Work-rate analysis of elite female soccer players during match-play.J Sports Sci Med2007;(Suppl.10):107—8.

100.Bangsbo J.Physiological demands.In:Ekblom B,editor.Handbook of sports medicine and science:football(soccer).Oxford,UK:Blackwell Scientifi c Publications;1994.p.43—58.

101.Green MS,Esco MR,Martin TD,Pritchett RC,M cHugh AN, Williford HN.Crossvalidation of two 20-m shuttle-run tests for predicting VO2maxin female collegiate soccer players.J Strength Cond Res2013;27:1520—8.

102.Jensen K,Larsson B.Variations in physical capacity among the danish national soccer team for women during a period of supplemental training.J Sports Sci1992;10:144—5.

103.Manson SA,Brughelli M,Harris NK.Physiological characteristics of international female soccer players.JStrengthCondRes2014;28:308—18.

104.M cCurdy KW,Walker JL,Langford GA,Kutz MR,Guerrero JM, M cM illan J.The relationship between kinematic determ inants of jump and sprint performance in division I women soccer players.J Strength Cond Res2010;24:3200—8.

105.Sjo¨kvist J,LaurentMC,Richardson M,Curtner-Smith M,Holmberg HC, Bishop PA.Recovery from high-intensity training sessions in female soccer players.J Strength Cond Res2011;25:1726—35.

106.Withers RT,Whittingham NO,Norton KI,La Forgia J,Ellis MW, Crockett A.Relative body fat and anthropometric prediction of body density of female athletes.Eur J Appl Physiol1987;56:169—80.

107.Arecheta C,Go´mez M,Lucı´a A.La importancia delVO2maxpara realizar esfuerzos interm itentes de alta intensidad en el fu´tbol femenino de e´lite (The importance of VO2maxforhigh intensity intermittentefforts in elite women’s soccer).Kronos2006;5:4—12.

Received 16 May 2014;revised 7 July 2014;accepted 2 September 2014 Available online 7 October 2014

*Corresponding author.Institute of Movement and Training Science,University of Leipzig,Leipzig,04109,Germany.

E-mail address:lagunas@uni-leipzig.de(V.Martı´nez-Lagunas)

Peer review under responsibility of Shanghai University of Sport

2095-2546/$-see front matter CopyrightⒸ2014,Shanghai University of Sport.Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.A ll rights reserved. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2014.10.001

CopyrightⒸ2014,Shanghai University of Sport.Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.All rights reserved.

Journal of Sport and Health Science2014年4期

Journal of Sport and Health Science2014年4期

- Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- Principles and practices of training for soccer

- The relative age effect has no influence on match outcome in youth soccer

- Stress hormonal analysis in elite soccer players during a season

- Effects of small-volume soccer and vibration training on body composition,aerobic fi tness,and muscular PCr kinetics for inactive women aged 20—45

- The acute effects of vibration stimulus follow ing FIFA 11+on agility and reactive strength in collegiate soccer players

- Concussion management in soccer