爆炸冲击波性脑损伤的发生机制和生物标志物研究进展

摘要: 爆炸冲击波性脑损伤( blast-induced traumatic brain injury, bTBI)是由爆炸时的冲击波对颅脑造成的损伤效应,伤者可表现出不同程度的躯体和行为障碍以及远期认知功能损害,是战时最常见的脑损伤类型。bTBI 的发生机制复杂且尚未完全阐明。爆炸产生的冲击波作用于头部表面并在颅内传播,造成颅脑弥漫性损伤,从病理学层面可将bTBI 分为原发性损伤和继发性损伤。冲击波的机械致伤效应会造成脑内结构的原发性受损,通常不可逆,只能采取有效的预防措施减少伤害。原发性损伤可引发一系列复杂的继发性级联反应,包括突触功能障碍、兴奋性毒性损伤、血脑屏障破坏、脑膜淋巴系统功能障碍、神经炎症、线粒体功能障碍、氧化应激反应、tau 蛋白过度磷酸化和淀粉样蛋白-β 病理改变等,可持续至伤后数天甚至慢性阶段,为临床治疗提供了干预的时间窗。轻度bTBI 临床表现异质性高,影像学表现常呈阴性,早期诊断困难。但近年来bTBI 的血液生物标志物取得长足进展,包括泛素C 末端水解酶L1、神经元特异性烯醇化酶、神经丝蛋白轻链、磷酸化tau 蛋白、髓鞘碱性蛋白、胶质纤维酸性蛋白、S100 钙结合蛋白B和其他新兴生物标志物等,有望成为影像学阴性的bTBI 的早期诊断和预后判断的潜在生物标志物。综上,本文重点综述了近年来关于bTBI 的发生机制和生物标志物研究的前沿进展,并展望了未来的研究方向,以期为探索bTBI 的发生机制、早期诊断策略和干预靶点提供新思路。

关键词: 爆炸冲击波性脑损伤;冲击波;发生机制;生物标志物

中图分类号: O383; R741 国标学科代码: 13035; 32054 文献标志码: A

创伤性脑损伤(traumatic brain injury, TBI)是指由外力引起的脑功能或脑病理学的改变[1],其致伤因素复杂,通常包括道路交通事故、意外坠落和暴力伤害等。爆炸是战时最常见的致伤因素,自2022 年2 月以来,俄乌冲突在两年间造成的30 457 名乌克兰平民伤亡中,91% 由广域爆炸性武器造成,包括火炮、坦克、导弹、空袭等,地雷和战争遗留爆炸物占3.7%[2]。现代战争中高爆武器的大量应用使爆炸冲击波成为战时TBI 最主要致伤因素,一项关于2001-2018 年的美军作战人员TBI 的回顾性研究显示,在46 309 名遭受了TBI 的服役人员中,有71% 是由于爆炸冲击波所致[3]。

爆炸冲击波性脑损伤(blast-induced traumatic brain injury,bTBI)是爆炸时产生的冲击波作用于头部引起的颅脑弥漫性损伤,是战时最常见的战创伤类型,伤死率高达30%,给卫勤保障带来了严峻挑战[4]。战时冲击波主要来自于爆炸型的武器、弹药,平时亦可发生于化学爆炸、烟花爆炸或工业事故等[5]。与传统意义上外伤导致的TBI 不同,bTBI 具有特殊的致伤机制、病理变化及临床表现,虽多无局灶性损伤,但可表现出精神行为症状和远期认知障碍,被认为是TBI 的一种独特类型。冲击波作用于脑组织的机制十分复杂,bTBI 的发生机制目前尚未完全阐明。此外,轻度bTBI 早期诊断困难,临床漏诊和延误诊断比例高,往往造成远期不可逆性神经功能损害。因此,揭示bTBI 的发生机制、探索早期诊断方法和有效干预靶点是该领域亟待解决的重要科学问题。本文综述bTBI 的发生机制及生物标志物研究进展,以期为探索bTBI 的发生机制和临床诊治策略提供新思路。

1 爆炸冲击波性脑损伤的主要临床表现

bTBI 的临床表现异质性强,伤员病情轻重不一,轻者可无明显症状或表现为不同程度的头晕头痛、记忆丧失、注意力不集中、焦虑行为等,严重者可死亡。远期可出现认知能力受损、行为改变、睡眠障碍、癫痫发作等[6],严重影响单兵作战能力和远期生活质量[7],增加了军队医疗成本及长期社会保障压力。

1.1 根据严重程度划分

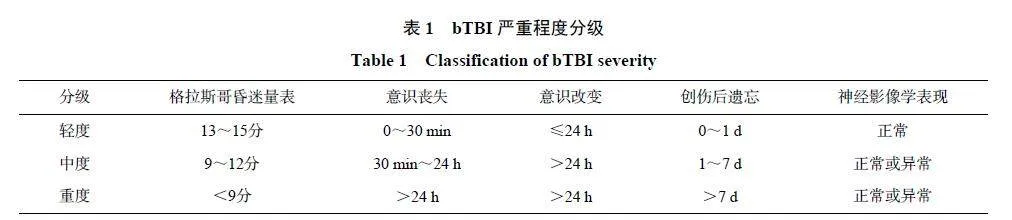

美国国防部TBI 指南[8] 根据格拉斯哥昏迷量表(Glasgow coma scale,GCS)、意识丧失(loss ofconsciousness,LOC)、意识改变(alteration of consciousness,AOC)、创伤后遗忘(post-traumatic amnesia,PTA)和神经影像学表现5 个方面,将bTBI 患者分为轻、中、重3 级,如表1 所示,其中以轻度最常见,占80% 以上[3, 9]。

轻度bTBI 患者最常见的表现是头痛、健忘、认知功能障碍、注意力分散、平衡受损、情绪改变和睡眠障碍,大部分患者计算机断层成像(computed tomography,CT)检查呈阴性,症状可在几小时或几天内消退,少数可持续数天甚至更长时间,出现脑震荡后综合征(postconcussive syndrome,PCS)[5, 10-11]。中度bTBI 患者可出现更长时间的意识丧失,常伴有逆行性或顺行性遗忘,头颅CT 检查可见阳性征象,如颅内出血、水肿等[12-13]。重度bTBI 患者伤情严重,头颅CT 多呈阳性,显示颅骨骨折、颅内出血和脑实质挫伤等,短时间内即可继发恶性脑水肿和脑血管痉挛,死亡率高达30%~40%[9, 11-12, 14]。

1.2 根据病情进展划分

由于冲击波的致伤机制复杂,且脑组织具有高度异质性,bTBI 患者在疾病进展过程中的表现也不完全相同。目前针对bTBI 的临床病情分期未有统一且明确的划分,故根据bTBI 的病情进展,概括梳理其临床表现如下。

颅脑冲击伤后急性期即可出现脑震荡相关临床表现,主要包括躯体(头痛、头晕、恶心等)、认知(信息处理能力下降、注意力分散等)和行为(暴躁易怒、情绪不稳、多动等)3 个方面的能力下降,大部分可在1~2 周内恢复,但10%~15% 的患者会持续更长时间[9, 15]。若头痛头晕、疲劳、注意力不集中、睡眠障碍、情绪改变等症状持续超过30 d 则称为PCS[15]。爆炸暴露可增加创伤后应激障碍(post-traumaticstress disorder,PTSD)罹患风险[5, 7]。具有爆炸暴露史的退伍军人可表现出明显的PTSD 症状,且与神经心理功能下降如信息处理速度减慢有关[16-17]。受伤后数月内,部分患者表现为头痛、疲劳、对光或声音敏感、认知障碍、注意力难以集中、重度抑郁、焦虑、睡眠障碍、神经内分泌失调等。PCS 和PTSD 症状表现有很大程度的重叠[9]。上述症状特异性不高,影像学检查多为正常,部分患者的神经精神症状可能持续存在至伤后数月,表现为慢性创伤性脑病(chronic traumatic encephalopathy,CTE)[9]。研究表明,CTE 与bTBI 病史密切相关[18],可表现出认知障碍、情绪障碍、行为改变、药物滥用和自杀等[19-20]。此外,TBI 可增大远期癫痫风险,且癫痫的发生率随TBI 严重程度的提高而上升[21]。

2 爆炸冲击波性脑损伤的发生机制

炸药爆炸后产生巨大的能量,推动周围介质(空气、水等)迅速膨胀并瞬间压缩形成冲击波,介质压力、密度和温度骤然升高达到峰值,而后随着冲击波的扩散和传播,指数衰减直至负压状态。bTBI 的主要致伤因素是爆炸发生后冲击波作用于头部表面并在颅内传播形成的应力波[5, 22]。因为战场环境多变,且脑组织异质性明显,bTBI 的生物力学机制十分复杂。目前研究公认最普遍的是波传播机制和颅骨变形机制,前者指冲击波经颅骨或经颅骨孔道传递至大脑引起脑损伤,后者指冲击波作用于颅骨,使颅骨产生局部弯曲变形进而导致颅内压的正负交替改变造成脑损伤。此外,冲击过程中脑内空化气泡破裂产生的微射流、加速效应导致的机械性损伤和胸腹部压缩产生的血涌都会造成脑组织不同程度的受损。上述致伤机制可同时存在且彼此间相互关联,受多种因素影响[5, 22-26]。

与钝性撞击导致的TBI 不同,由于颅骨的整体暴露,bTBI 通常表现为弥漫性损伤[27]。从病理学层面可分为原发性损伤和继发性损伤,原发性损伤指因冲击波致伤效应导致的脑组织的直接机械损伤,具有不可逆性,只能采取有效的预防措施减少伤害[28-29]。继发性bTBI 是指冲击波致伤后数小时或数天内,由原发性损伤引发的一系列复杂的级联反应,可持续至伤后数天甚至慢性阶段,为临床治疗提供了一个干预时间窗[28-30]。结合当前研究进展,简要总结bTBI 的主要病理过程如图1 所示。

2.1 弥漫性轴索损伤

弥漫性轴索损伤(diffuse axonal injury,DAI)是bTBI 的典型病理特征。爆炸暴露引起的DAI 和持续性轴突变性与bTBI 后慢性神经精神症状有关,是导致长期认知功能障碍和死亡的重要内因[31-33]。冲击波颅内传播时,因为脑组织的旋转、变形或位移,作用于轴突的轴向应力和剪切应力会造成轴突的原发机械损伤,包括旋转、拉伸和压缩[34]。脑白质包含大量的神经纤维束,且相邻结构密度不同,因此最易受损[35]。DAI 后微管蛋白水解致微管稳定性下降,神经丝蛋白结构改变,肌动蛋白环-血影蛋白复合物间距增大,轴突骨架破坏[36]。轴突运输中断,轴突内转运的蛋白质如β-淀粉样蛋白前体蛋白( β-amyloidprecursor protein,β-APP)等快速积累,导致轴突肿胀。通过免疫组织化学技术检测APP 积累是目前评估轴突损伤的金标准[37]。部分神经元轴突远端与胞体间发生不可逆性断裂,伴有髓鞘的丢失[32]。除原发性的机械损伤外,DAI 还与许多继发损伤相互影响构成复杂的级联反应,如线粒体功能障碍、氧化应激反应、钙离子失衡等,进一步加重脱髓鞘和轴突变性[37-39]。随着时间的推移,持续的神经元回路功能障碍和白质束轴突变性,引发长期的进行性神经退行性变[32]。

2.2 脑血管损伤

冲击波的机械损伤效应可导致脑血管结构的缺失和完整性受损[27]。Chen 等[40] 研究发现,爆炸冲击波可损伤血管内皮细胞表面的糖萼结构,导致脑血管功能障碍和血脑屏障(blood-brain barrier, BBB)受损。轻度爆炸伤一般不会引起明显的局灶性出血,但可损伤小血管并诱导持续的局灶性创伤性微血管损伤,中重度可能会导致颅内出血和水肿,甚至形成延迟性血管痉挛和假性动脉瘤[5, 41-42]。在多种急性冲击波损伤动物模型中,通过肉眼和显微镜可见硬膜下、蛛网膜下和脑实质出血,且其严重程度与冲击波超压大小和距离相关[43-44]。bTBI 大鼠急性期、亚急性期和慢性期的高分辨CT 结果显示,爆炸暴露后48 h 就可在部分脑区观察到血管闭塞,6 周可见到脑血管排列紊乱和灌注不足,13 个月时脑血管变性更加明显[45]。并且既往有过爆炸暴露的轻度bTBI 退伍军人在5 年后血浆中血管内皮生长因子-A(vascular endothelial growth factor-A,VEGF-A)仍显著高于对照组,进一步提示慢性血管功能障碍[46]。

2.3 突触功能障碍

Wang 等[47] 研究发现,bTBI 急性期即可在听觉皮层发现突触传递受损和树突改变。轻度bTBI 小鼠可出现顶叶皮层和海马的树突密度降低、分支减少,且顶叶皮层的中间层尤为明显[48]。电镜下可在bTBI 脑组织中观察到神经元核周变暗、内质网扭曲、线粒体肿胀、轴突微管紊乱和突触密度降低,皮质兴奋性突触丧失而海马兴奋性突触增加[49]。多项大鼠海马切片的体外爆炸实验表明,爆炸暴露可以诱导体外培养的海马切片长时程增强作用降低[50-51],突触完整性受损,突触传递障碍,降低与认知障碍相关的突触蛋白表达[52]。另外,Tagge 等[42] 研究发现,TBI 后小鼠海马轴突传导速度出现急性、持续性下降,部分大脑区域的短时程和长时程活动依赖性突触可塑性降低。

2.4 兴奋性毒性

谷氨酸是由大脑神经元释放的主要兴奋性神经递质,其作用于突触后膜的神经递质受体主要包含2 种:主要门控Ca2+内流的N-甲基-D-天冬氨酸受体(N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor,NMDAR)和主要门控Na+内流的α-氨基-3-羟基-5-甲基-4-异恶唑丙酸受体(α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionicacidreceptor,AMPAR),两者在神经元兴奋性递质传递和突触可塑性中发挥至关重要的作用[53]。爆炸暴露可引起细胞外谷氨酸水平升高,诱导谷氨酸受体异常过度激活,细胞内Ca2+水平激增,谷氨酸能神经元过度兴奋,和相关第二信使系统的变化,最终诱导神经元损伤和细胞死亡,并且神经递质传递障碍的持续累积,以及其与氧化应激、线粒体功能障碍、神经炎症等继发性级联反应的复杂相互作用,导致突触可塑性受损和长期认知功能障碍[53-56]。海马神经元的高密度NMDAR 可能是该部位易受兴奋性毒性损伤的原因[57]。

2.5 血脑屏障破坏

BBB 由脑毛细血管内皮细胞、细胞间的紧密连接、基膜、周细胞以及星形胶质细胞终足形成的神经胶质膜构成,生理情况下可阻碍外来病原体和免疫介质进入大脑,其基本结构和功能单位是由内皮细胞及其支持的神经胶质细胞和神经元构成的神经血管单元(neurovascular unit,NVU),若NVU 内的细胞元件受到冲击波的干扰,则会引起BBB 的破坏和一系列继发性改变[58]。爆炸发生后,内皮细胞、血管平滑肌细胞、周细胞损伤,星形胶质细胞终足肿胀,细胞间紧密连接被破坏,BBB 受损[42-44, 59],同时神经炎症和神经胶质细胞活化又可释放多种炎症介质加剧BBB 的破坏[60]。BBB 损伤后内皮完整性受损、血管平滑肌变性、神经胶质血管损伤、细胞外基质重组、血管重塑,影响脑内血液、脑脊液流动,细胞外液体积聚,进而引发血管源性水肿、颅内压升高及其他继发性损伤,使认知和行为发生改变[43, 45, 61]。除血管源性水肿外,引起bTBI 后脑水肿的原因还包括细胞毒性水肿。许多研究都表明水通道蛋白4(aquaporin-4,AQP4)可能参与TBI 后脑水肿的发生发展与转归[60, 62]。AQP4 主要在星形胶质细胞中表达,介导了TBI 后因细胞(如星形胶质细胞)内过度水潴留导致的细胞毒性水肿[60]。

2.6 脑膜淋巴系统功能障碍

脑膜淋巴管参与大分子物质、细胞碎片和免疫细胞从大脑向外周引流的功能,维护脑内稳态。有蛋白组学研究在液压冲击伤小鼠模型脑膜淋巴系统外周远端的颈深淋巴结中发现了脑源性蛋白富集和BBB 相关蛋白的功能失调,提示脑膜淋巴系统参与TBI 发生发展[63]。近几年的研究表明,TBI 可诱导脑膜淋巴系统形态改变和功能障碍[64],TBI 后脑膜淋巴管内皮细胞受损致脑膜淋巴管生成障碍,颅内有害代谢物质清除受阻[65],进而引发脑水肿和颅内压升高[66]。恢复脑膜淋巴引流功能,促进脑脊液引流和脑水肿吸收,可减轻神经炎症并降低活性氧(reactive oxygen species,ROS)形成,改善预后[64, 66]。重复爆炸的小鼠模型研究提示AQP4 的表达增加和定位改变介导了bTBI 后的延迟性淋巴功能损伤[67]。近来研究发现,脑淋巴引流障碍可引起tau 蛋白、淀粉样蛋白-β(amyloid-β,Aβ)清除受阻,导致认知障碍[68-69]。

2.7 神经炎症

颅脑创伤后神经炎症反应既有神经保护作用又可引起额外脑损伤[70]。冲击波致伤脑组织后,损伤相关分子模式被释放,诱导局部细胞因子和趋化因子如白介素(interleukin,IL)-1β、IL-6、肿瘤坏死因子(tumor necrosis factor,TNF)-α 等产生,引起固有免疫应答,使得下游免疫细胞和神经胶质细胞活化后增生并募集到损伤区域进行修复[71]。急性反应的细胞主要包括中性粒细胞、星形胶质细胞、小胶质细胞、单核细胞或巨噬细胞和T 细胞等。中性粒细胞最先反应,迅速募集到中枢神经系统进行修复,但同时又可释放金属蛋白酶、TNF、ROS 等加重BBB 分解[72]。3~5 d 后中性粒细胞减少,同时损伤部位周围单核-巨噬细胞浸润,神经胶质细胞激活。反应性星形胶质细胞增生,分泌炎症介质并促进小胶质细胞和其他免疫细胞的活化,从而诱导持续的神经炎症[60, 73-74]。慢性bTBI 患者的尸检研究显示在软膜下胶质板、穿透皮质的血管、灰/白质交界和脑室内壁等结构处有明显的星形胶质细胞瘢痕形成,急性bTBI 病例亦在相同区域表现出早期反应性星形胶质细胞增生[74]。此外,小胶质细胞也在创伤后快速激活并显示出向反应性更强的表型转变[70, 75],既促进炎症反应,又具有神经修复保护作用,并且随着神经炎症的发展,小胶质细胞活化可持续数年[76]。在随后的时间点,由T 细胞和B 细胞介导的适应性免疫反应参与损伤后的炎症修复[70-71]。受伤后2 周,大脑基本无免疫细胞浸润,但活化的星形胶质细胞、小胶质细胞和细胞因子等可持续至慢性阶段,且有证据表明bTBI 后神经退行性变与慢性炎症具有相关性[74, 76-77]。

2.8 线粒体功能障碍与氧化应激反应

线粒体损伤是bTBI 的标志性事件,可导致代谢功能障碍,最终导致细胞死亡。有研究表明,原发性低强度爆炸会诱导与线粒体功能障碍有关的氧化应激反应增加,线粒体裂解-融合受损、线粒体自噬、氧化磷酸化降低和呼吸相关的酶活性代偿等分子机制是导致后期神经退行性变的重要因素[78]。bTBI 后,过量的细胞内Ca2+可驱动线粒体产生ROS,诱导氧化应激反应的发生。ROS 过量产生可诱导细胞和血管结构的过氧化、蛋白质氧化和线粒体电子传递链抑制,引起氧化性细胞损伤[79]。ROS 可进一步诱导炎症细胞因子产生,破坏BBB 完整性,引起更广泛的病理改变如脑缺血和水肿[80]。爆炸暴露后的氧化应激反应在提高BBB 通透性[81]、突触功能障碍和慢性神经炎症[82] 等病理进展中起到重要的协同作用。另外,有研究发现细胞外线粒体在TBI 后增加,并以ROS 依赖性方式结合和激活M1 型小胶质细胞,加重TBI 的神经炎症和脑水肿[83]。

2.9 tau 病理

tau 蛋白是一种在神经元中高表达的微管结合蛋白,主要作用是稳定轴突微管[84]。bTBI 后,脑内过度磷酸化tau 蛋白(hyperphosphorylated tau protein,p-tau)显著增加,破坏微管稳定性,致使突触可塑性下降和认知能力受损[84-85]。由p-tau 在血管周围聚集形成的神经原纤维缠结(neurofibrillary tangle,NFT)是CTE 的主要病理特征之一,其他常见神经病理学特征包括小胶质细胞和星形胶质细胞增多、髓鞘轴突病变和进行性神经退行性变等[18-20, 41]。有研究对纳入的10 名bTBI 退伍军人进行了tau 蛋白正电子发射计算机断层扫描(positron emission tomography,PET)脑显像,发现了其中一半的受试者脑内tau 蛋白分布于额叶、顶叶和颞叶的灰/白质交界,符合CTE 典型病理改变,表明了爆炸损伤与CTE 之间的相关性[86]。与CTE 相关的p-tau 病理改变由血管周围的神经元细胞驱动,并且与头部反复创伤暴露年限及CTE 严重程度显著相关[87]。有研究发现,TBI 小鼠12 h 内神经元即可急性产生一种异常的顺式p-tau,从而破坏轴突微管网络和线粒体转运,并导致细胞凋亡[88]。对CTE 病人脑中tau 纤维丝的冷冻电镜研究揭示了CTE 中tau 的构象与阿尔茨海默病(Alzheimerʼs disease,AD)和皮克病明显不同,表明tau 蛋白运输和聚集的机制在不同的神经退行性疾病中可能具有特异性的差异[89]。

2.10 Aβ 病理

颅脑爆震伤患者可表现出Aβ 病理,其来源与轴突受损后APP 积累有关[37],但目前其病理变化和发生机制尚不清楚,且bTBI 人群与AD 患者的典型Aβ 病理改变存在差异,仍有待进一步研究。一项纳入了30 名既往接受过爆炸暴露的美国现役人员研究显示,bTBI 人群的血清Aβ40 和Aβ42 水平与健康对照组相比明显升高[90]。有bTBI 人群的淀粉样蛋白PET 脑显像结果显示爆炸暴露后淀粉样蛋白在部分脑区沉积显著增加[91],少部分bTBI 人群的尸检结果也发现了Aβ 斑块[20, 92-93]。但啮齿动物bTBI 模型显示爆炸暴露后脑内Aβ42 水平降低,APP/PS1 转基因小鼠在接受爆炸暴露后出现认知功能改善和Aβ42 水平长期降低[94-95]。另外,最近也有bTBI 队列研究发现患有爆炸相关轻度脑损伤的中年退伍军人脑脊液中Aβ40 和Aβ42 水平均低于无脑损伤对照组[96]。有CTE 患者尸检研究显示其脑脊液中Aβ42 水平低于AD 患者,且低级别CTE 患者的Aβ42 水平低于无CTE/无AD 对照组[97]。既往有研究将TBI 列为AD 发病的危险因素,但也有大型临床队列研究表明,未能发现两者之间在神经病理学和临床表型等方面的相关性[98-99]。

3 爆炸冲击波性脑损伤的生物标志物

3.1 影像学生物标志物

目前评估bTBI 的影像诊断手段众多,包括CT、磁共振成像(magnetic resonance imaging,MRI)、经颅多普勒、磁共振波谱(magnetic resonance spectroscopy,MRS)、电生理技术(脑磁图和脑电图)和PET 等。因为bTBI 伤情的异质性,没有一种影像评估手段适用于所有患者,因此,有必要综合考量,以便在物理层面实现脑损伤可视化[54]。

CT 检查快速、简便,对急性出血和骨折敏感,是排除中重度bTBI 的首选方式[100]。但是,CT 识别bTBI 白质病变的灵敏度有限,假阴性较高,而且对DAI 和相关血管损伤的敏感性不足。MRI 对神经结构损伤的分辨率高,可通过综合不同序列实现对bTBI 后不同病理改变的早期识别:磁共振成像液体衰减反转恢复序列可识别bTBI 中的白质高信号;磁敏感加权成像对脑微出血特别敏感;MRS 可用于检测脑损伤后代谢成分改变;磁共振弥散加权成像能够检测受损后脑组织内水分子弥散运动情况;功能性MRI 通过血氧水平依赖性信号的变化来评估神经元活动和脑功能;磁共振弥散张量成像(diffusion tensorimaging,DTI)能够间接通过水分子弥散运动的各向异性,对脑白质纤维束结构进行成像[9, 101]。

DTI 能够显示颅脑损伤后脑白质纤维束结构的完整性和微观组织变化,现已成为bTBI 诊断和预后评估公认有效的影像生物标志物,常表现为各向异性(fractional anisotropy,FA)降低和平均扩散系数(mean diffusivity,MD)升高,其余常用参数还有表观扩散系数、径向扩散率(radial diffusivity,RD)和轴向扩散率等[102-103]。有研究对72 名患有bTBI 的退伍军人和21 名未患有bTBI 的退伍军人的DTI 图像进行了比较,发现患有轻度bTBI 的退伍军人显示出多灶性白质异常的证据,与损伤的严重程度和神经心理学表现都具有相关性,表明DTI 是识别bTBI 后脑白质完整性的敏感生物标志物[104]。有研究团队招募了20 名bTBI 人员及14 名对照,DTI 结果显示FA 值显著降低而RD 显著升高,与慢性白质损伤结论一致[105]。一项多中心临床研究发现,与健康对照组相比,轻度TBI 患者MD 值升高、FA 值降低,且其可较准确地预测患者6 个月后的临床结局,表明DTI 对轻度TBI 患者具有一定的早期诊断和预后评估价值[106]。一项关于中重度TBI 患者的纵向研究发现,DTI 对DAI 的脑白质萎缩具有很强的预测作用,提示DTI 检测有助于准确判断DAI 患者远期神经退行性变的风险[107]。

3.2 血液生物标志物

结合现有bTBI 和TBI 的生物标志物研究,目前对bTBI 严重程度的评估主要依靠临床评估和影像学检查,但GCS 评分对有意识障碍或气管插管的患者应用受限,且评估脑损伤预后的能力有限。头颅MRI 较CT 对更小病灶的识别有显著优势,但考虑到bTBI 患者可能合并有金属碎片影响成像效果以及军事特殊作业环境缺乏MRI 设备,寻找便于检测的血液生物标志物是探索bTBI 伤情评估手段的重要方向[108-113]。对于可能适用于bTBI 人群的血液生物标志物简要总结如图1 所示,以下对bTBI 的可能血液生物标志物和新兴标志物研究进展进行了讨论。

3.2.1 神经元胞体损伤

泛素C 末端水解酶L1(ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase L1,UCH-L1)是一种在神经元中高表达的去泛素化酶[109],血液UCH-L1 可以作为bTBI 急性期的生物标志物。2018 年,UCH-L1 被美国食品药品监督管理局授权应用于12 h 内轻度TBI 的血液检测,以减少颅脑创伤诊断过程中不必要的CT 扫描[114-115]。有研究纳入了30 名既往接受过爆炸暴露的军队人员,与健康对照组相比,血清UCH-L1 水平显著升高[90]。对108 名参加为期 2 周的爆炸训练军人的血清UCH-L1 急性变化研究发现,UCH-L1 水平因爆炸暴露而升高但与爆炸强度相关性弱,与神经认知表现无相关性[116]。但另一项对29 名军队人员爆炸超压暴露前后血清生物标志物改变的研究显示,血清UCH-L1 水平在急性爆炸后有头晕症状的人群中出现有统计学意义的升高[117]。另外,多项研究指出,UCH-L1 对于TBI 后的功能结局具有预测作用[118-120]。一项研究招募了1 696 名受试者,针对TBI 受伤后当日血浆UCH-L1 预后能力进行研究,发现UCH-L1 对死亡和不良结局预测较好,但对6 个月时不完全恢复情况的预测能力有限[119]。

神经元特异性烯醇化酶(neuron-specific enolase,NSE)主要存在于神经元胞体中的一种糖酵解酶,在神经元损伤时释放到细胞外,可作为评价神经元损伤严重程度的生物标志物[109]。NSE 对bTBI 的严重程度具有诊断效能,但准确性相对较弱[121],也是不良临床结局的预测指标[122]。一项临床研究纳入了104 名特种部队作战人员,发现既往患有轻度TBI 的人群(55 例)血液NSE 水平较健康对照(49 例)显著升高[123]。有研究表明,血清NSE 水平与轻度TBI 后PCS 临床表型无显著关联,提示预后价值有限[124],但另一项研究发现中重度TBI 患者的血清NSE 水平升高与不良结局(死亡率及GCS≤3)之间具有相关性[125]。一项纳入63 名中重度TBI 患者的临床研究表明,血清NSE 对脑干损伤诊断的灵敏度为100%,可避免20%的MRI 检查[126]。然而,NSE 也存在于红细胞中,溶血可增加血液NSE 水平,因此,其作为血液生物标志物的用途受限[109-110]。

3.2.2 神经元轴突损伤

神经丝蛋白轻链(neurofilament protein-light,NfL)是细胞骨架蛋白之一,在有髓神经元中高表达,是评估轴突变性最成熟的生物标志物之一[110-111]。多项研究证明了血液NfL 是TBI 的有力生物标志物,其在亚急性期和慢性期的诊断和预后评估能力更明显[127-128]。有研究对195 名既往患有bTBI 的退伍军人血液生物标志物进行了检测,发现血浆NfL 水平升高与爆炸暴露次数呈正相关性,并且可持续升高至慢性阶段,在患有慢性PCS、PTSD 和抑郁症状的人群中更明显[33]。对34 名参加爆炸培训计划的军人爆炸暴露后30 min 的血样进行检测,发现NfL 水平在反复爆炸暴露后出现显著升高[129]。另一项纳入197 名重度TBI 患者的多中心队列研究分析了TBI 后血液生物标志物、DTI 与临床结局的关系,发现血浆NfL 在损伤后迅速增加,于亚急性期(10 d 到6 周)达到峰值,在6 个月和1 年时仍明显高于正常水平,且血浆NfL 水平与DTI 测量值具有相关性。而且,在预测6 个月和1 年时的神经退行性变结局方面,亚急性期的血浆NfL 水平表现出了最强的预测能力,其次为DTI 的FA 评分[130]。一项纳入了230 名TBI 患者的研究发现,NfL 不仅可以对TBI 严重程度进行区分,血清NfL 与TBI 的远期功能结局和神经退行性变亦具有相关性[128]。最近一项对143 名TBI 患者长达5 年的横断面和纵向研究结果显示,血清NfL 能够独立预测TBI 后的脑萎缩进展[131]。

磷酸化tau 蛋白( p-tau)是一种在神经元中高表达的微管结合蛋白,主要作用是稳定轴突微管[84]。CTE 患者尸检研究中,脑脊液中p-tau231 水平与对照组和AD 患者相比显著升高[97]。血液tau 蛋白水平能够表征TBI 和CTE 的轴突病理损伤[132-133]。34 名参加爆炸培训计划的军人在接受反复爆炸暴露后30 min 的血液总tau 蛋白(total tau protein, t-tau)和p-tau181 水平均出现显著升高[129]。一项纳入了30 名美国现役人员的研究也显示急性爆炸暴露后受试者的血清t-tau 水平显著升高[90]。为探索血浆p-tau 和p-tau/t-tau 对急慢性TBI 的早期诊断效能和预后价值,有研究纳入196 例急性TBI 患者和21 例慢性TBI 患者,发现急性TBI 患者血浆t-tau、p-tau 和p-tau/t-tau 均显著高于对照组,p-tau、p-tau/t-tau 水平可用于区分TBI 的严重程度,且慢性TBI 患者血浆p-tau、p-tau/t-tau 也显著高于对照组。对于区分CT 结果为阳性/阴性方面,p-tau 和p-tau/t-tau 的AUC(受试者工作特征曲线下的面积,area under curve)分别为0.921 和0.923,显示出准确的鉴别能力[133]。此外,血浆p-tau 和p-tau/t-tau 水平对6 个月时的不良预后具有一定的预测能力(AUC 分别为0.771 和0.777)[133]。最近一项研究显示,血清tau 水平与TBI 的症状加重具有相关性,表明tau 或可作为TBI 不良预后的预测因子[134]。

髓鞘碱性蛋白(myelin basic protein,MBP)是中枢神经系统的少突胶质细胞和周围神经系统的雪旺细胞形成髓鞘的主要蛋白成分[109, 111]。bTBI 后白质纤维束损伤,进而发生脱髓鞘病变和少突胶质细胞死亡,释放MBP 到脑脊液,随后经BBB 入血[135]。MBP 在血液中浓度较低,且通常在TBI 后2~3 d 释放入血,因此血液检测和急性筛查用途受限,但血液MBP 一旦升高可持续2 周,且MBP 作为表征轴突损伤的标志物具有较高的特异性[136-138]。TBI 患者的血液和脑脊液MBP 水平显著高于健康对照[139-140],但近年来关于bTBI 人群血液MBP 变化的临床研究少见。一项纳入了131 例TBI 患者的临床研究显示,血清MBP 水平与TBI 严重程度呈正相关,并且能够预测和区分TBI 后6 个月时的不同的功能结局,表明血清MBP 对TBI 具有一定的诊断和预后价值[141]。

3.2.3 神经炎症

胶质纤维酸性蛋白(glial fibrillary acidic protein,GFAP)是星形胶质细胞骨架蛋白,作为TBI 后星形胶质细胞活化的生物标志物被广泛研究[110],其对急性期TBI[127] 特别是头部CT 扫描不可见的亚临床颅内病变诊断准确性很高[142-143]。2018 年美国食品药品监督管理局授权GFAP 应用于12 h 内轻度TBI 的血液检测[114]。法国急诊医学会也推荐GFAP 用于非穿透性TBI 的早期诊断[144]。一项纳入了1 959 例轻中度TBI 患者(其中头颅CT 阳性者为6%)的研究发现,血清GFAP 对头颅CT 阴性的轻度TBI 患者具有很高的诊断效能,其对CT 颅内损伤识别的灵敏度为0.976,阴性预测值为0.996[114]。此外,GFAP 对TBI 也有一定预后价值。一项纳入143 例TBI 患者的纵向研究发现,血清GFAP 能够独立预测TBI 后的脑萎缩进展[131]。另一项招募了1 696 名TBI 患者的纵向研究中,TBI 后当日的血浆GFAP 水平在预测死亡(AUC 为0.87)和不良结局(AUC 为0.86)方面的能力较高,但对6 个月后不完全恢复(AUC 为0.62)的预测能力有限[119]。对30 名既往接受过爆炸暴露的美国现役人员的研究显示,其血清GFAP 水平高于对照组,但差异无统计学意义[90]。在另一些临床研究中bTBI 人群的血液GFAP 水平则表现出降低,这一点与TBI 人群相反[94, 117, 129, 145-147],目前原因不明。一项研究招募了550 名患有TBI 的退伍军人,其中78.18% 至少经历过一次爆炸暴露,自最近一次轻度TBI 发生以来的平均时间为9.15 年(0~46 年),研究结果表明,与无爆炸暴露史人群相比,bTBI 人群的血浆GFAP 显著降低,并且和更严重的神经精神行为(PTSD、抑郁、神经行为症状等)有关[147]。上述研究得到了GFAP 降低的结论,但既往在bTBI 尸检结果[74]和动物实验[148-150] 中都发现了反应性星形胶质细胞增生的证据,因此,较低的GFAP 水平是否是bTBI 独特的损伤特征,有待进一步研究。

S100 钙结合蛋白B(S100 calcium-binding protein B,S100B)是一种细胞内钙结合蛋白,主要由星形胶质细胞合成,血液S100B 是TBI 急性期生物标志物,与TBI 严重程度和预后有关[110]。S100B 是首个被纳入TBI 指南的生物标志物,先后被斯堪的纳维亚成人轻中度颅脑损伤管理指南和法国急诊医学会指南推荐用做TBI 早期诊断和是否需要CT 扫描的分层诊疗证据[ 1 4 4 , 1 5 1 ]。将其纳入指南后至少减少了30% 的CT 扫描需求,但S100B 也存在局限性,如半衰期短(需要在TBI 后3 h 内采血)以及缺乏神经特异性(存在颅外释放)[152]。S100B 检测颅脑损伤的敏感性很高,基于近2 000 名轻度颅脑损伤患者的前瞻性研究发现血清S100B 鉴别CT 结果的敏感性和阴性预测值分别为98.2% 和99.5%,而鉴别临床相关颅内并发症的敏感性和阴性预测值则分别为100% 和100%[153]。但最近的一项研究纳入了933 例轻度TBI 患者,发现在损伤后6 h 内、>6~9 h、>9~12 h,血清GFAP 和UCH-L1 诊断TBI 后颅内损伤的敏感性和特异性以及对TBI 患者的结局预测能力均高于S100B[115]。 bTBI 大鼠模型的免疫组化研究显示,爆炸暴露后1 h,S100B 即可存在,24 h 分布更均匀,3 周时仍可检测到[148],但目前S100B 诊断bTBI 的临床队列研究少见。

3.2.4 其他新兴生物标志物

近年来,细胞外囊泡(extracellular vesicles,EV)和外泌体作为TBI 的新兴生物标志物受到关注[111]。EV 是不同细胞分泌到体液中的膜状颗粒,参与细胞间信号传递[154]。在多项研究中发现了bTBI/TBI 患者血液EV 中相关生物标志物水平的升高,包括GFAP、NfL、tau 蛋白、MBP、CD13、CD196、MOG、CD133 等[155-157]。外泌体是EV 的其中一种亚型,其内包含的微小核糖核酸(microRNA,miRNA)转运至受体细胞后在转录后基因表达调控中发挥重要作用[154]。最近一项研究通过高通量测序技术发现了TBI 后血清中245 个外泌体miRNA 发生显著变化,并鉴定了与神经一系列继发性损伤相关的血清外泌体miRNA 表达谱改变,包括8 个上调的miRNA(miR-124-3p、miR-137-3p、miR-9-3p、miR-133a-5p、miR-204-3p、miR-519a-5p、miR-4 732-5p 和miR-206)和2 个下调的miRNA(miR-21-3p 和miR-199a-5)[158]。

目前,关于TBI 后血液中miRNA 水平变化的研究众多。一项纳入了47 名受试者的临床研究显示,重度TBI 患者血浆中miR-765、miR-16、miR-92a 作为TBI 生物标志物的AUC 值分别为0.89、0.82 和0.86,这些生物标志物组合后对区分重度TBI 和健康对照人群具有100% 的敏感性和特异性[159]。一项纳入了5 名轻度TBI 和5 名重度TBI 患者的临床研究显示,miR-425-5p 和miR-502 是诊断轻度TBI 的有效生物标志物,miR-21 和miR-335 是诊断重度TBI 的有效生物标志物,且miR-425-5p 和miR-21 对TBI 后6 个月时的功能结局能够较好预测[160]。另外,miR-320c、miR-92a、miR-126-3p、miR-3 610、miR-206、miR-549a-3p、miR-let-7i 等都与bTBI/TBI 有较好的相关性,显示出miRNA 作为TBI 诊断和预后生物标志物的潜力[161-164]。

综上,GFAP 和S100B 是急性期TBI 的有效诊断生物标志物,且具有一定的预后判断能力,但还需进一步发掘其在bTBI 人群中的表现。在bTBI 亚急性期和慢性期,NfL 表现最佳,并且对临床结局具有很强的预测作用。UCH-L1 和p-tau 也可作为bTBI 的候选血液生物标志物。NSE 虽对疾病具有一定诊断能力但血液检测用途受限。近年来关于MBP 在bTBI/TBI 后的研究较少,虽然特异性高,但血液中浓度过低且急性筛查受限。此外,外泌体和miRNA 作为TBI 新兴生物标志物受到广泛关注,但需进一步深入研究验证其在爆炸性颅脑损伤早期诊断和预后中的临床价值。另外,当前针对特定颅脑爆震伤人群的生物标志物临床研究有限且多数研究纳入病例数较少,但考虑到bTBI 是一种特殊类型的TBI,上述内容参考和借鉴了当前TBI 人群的血液生物标志物研究内容。值得注意的是,虽然两者发生机制和易损靶点有很大程度的重叠,但尚有诸多不同之处且机制未明,TBI 的生物标志物对于bTBI 人群的实际适用性还需要进一步临床验证。

4 小结和展望血管重塑、BBB 完整性、神经炎症和

首先,bTBI 的致伤机制复杂,且占绝大多数比例的轻度bTBI 脑内关键病理变化尚不清楚,细胞和分子层面机制解析不足,未来亟需从时间和空间维度上探索bTBI 是否存在脑区易感性和易损细胞类型。其次,当前对轻度bTBI 的远期损害关注较少,未来需建立bTBI 临床队列,明确轻度bTBI 的远期神经损害特征,为提高bTBI 战伤救治提供科学依据。此外,目前的影像诊断手段难以早期捕捉到细微神经损害,导致轻型bTBI 的临床漏诊和延误诊断比例较高。最近多种血液生物标志物显示出反映早期轻度脑损伤的潜力,未来需进一步在大样本bTBI 临床队列中验证它们在早期诊断和预测疾病进展中的临床价值,明确bTBI 血液生物标志物划界值范围,建立bTBI 的早期筛查和预警体系。

参考文献:

[1]MORTIMER D S. Military traumatic brain injury [J]. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America, 2024,35(3): 559–571. DOI: 10.1016/j.pmr.2024.02.008.

[2]Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Two-year update-protection of civilians: impact ofhostilities on civilians since 24 February 2022 [EB/OL]. (2024-02-22)[2024-09-05]. https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/country-reports/two-year-update-protection-civilians-impact-hostilities-civilians-24.

[3]DENGLER B A, AGIMI Y, STOUT K, et al. Epidemiology, patterns of care and outcomes of traumatic brain injury indeployed military settings: implications for future military operations [J]. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 2022,93(2): 220–228. DOI: 10.1097/TA.0000000000003497.

[4]夏照帆, 伍国胜. 创伤性脑损伤的临床研究进展 [J]. 第二军医大学学报, 2021, 42(2): 117–121. DOI: 10.16781/j.0258-879x.2021.02.0117.

XIA Z F, WU G S. Traumatic brain injury: a clinical research progress [J]. Academic Journal of Second Military MedicalUniversity, 2021, 42(2): 117–121. DOI: 10.16781/j.0258-879x.2021.02.0117.[5]ROSENFELD J V, MCFARLANE A C, BRAGGE P, et al. Blast-related traumatic brain injury [J]. The Lancet Neurology,2013, 12(9): 882–893. DOI: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70161-3.

[6]张文超, 王舒, 梁增友, 等. 爆炸冲击波致颅脑冲击伤数值模拟研究 [J]. 北京理工大学学报, 2022, 42(9): 881–890. DOI:10.15918/j.tbit1001-0645.2021.191.

ZHANG W C, WANG S, LIANG Z Y, et al. Numerical simulation on traumatic brain injury induced by blast waves [J].Transactions of Beijing Institute of Technology, 2022, 42(9): 881–890. DOI: 10.15918/j.tbit1001-0645.2021.191.

[7]HOGE C W, MCGURK D, THOMAS J L, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury in U. S. soldiers returning from Iraq [J]. NewEngland Journal of Medicine, 2008, 358(5): 453–463. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa072972.

[8]Management of Concussion/mTBI Working Group. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for management of concussion/mildtraumatic brain injury [J]. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 2009, 46(6): CP1–68.

[9]KIM S Y, YEH P H, OLLINGER J M, et al. Military-related mild traumatic brain injury: clinical characteristics, advancedneuroimaging, and molecular mechanisms [J]. Translational Psychiatry, 2023, 13(1): 289. DOI: 10.1038/s41398-023-02569-1.

[10]MAAS A I R, MENON D K, ADELSON P D, et al. Traumatic brain injury: integrated approaches to improve prevention,clinical care, and research [J]. The Lancet Neurology, 2017, 16(12): 987–1048. DOI: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30371-X.

[11]LING G S, ECKLUND J M. Traumatic brain injury in modern war [J]. Current Opinion in Anesthesiology, 2011, 24(2):124–130. DOI: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e32834458da.

[12]CAPIZZI A, WOO J, VERDUZCO-GUTIERREZ M. Traumatic brain injury [J]. Medical Clinics of North America, 2020,104(2): 213–238. DOI: 10.1016/j.mcna.2019.11.001.

[13]DAVIS L E, PIRIO RICHARDSON S. Traumatic brain injury and subdural hematoma [M]//DAVIS L E, PIRIORICHARDSON S. Fundamentals of Neurologic Disease. 2nd ed. New York: Springer, 2015: 225–233. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2359-5_18.

[14]MAGNUSON J, LEONESSA F, LING G S F. Neuropathology of explosive blast traumatic brain injury [J]. CurrentNeurology and Neuroscience Reports, 2012, 12(5): 570–579. DOI: 10.1007/s11910-012-0303-6.

[15]EME R. Neurobehavioral outcomes of mild traumatic brain injury: a mini review [J]. Brain Sciences, 2017, 7(5): 46. DOI:10.3390/brainsci7050046.

[16]CLAUSEN A N, BOUCHARD H C, Workgroup M A M, et al. Assessment of neuropsychological function in veterans withblast-related mild traumatic brain injury and subconcussive blast exposure [J]. Frontiers in Psychology, 2021, 12: 686330.DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.686330.

[17]JURICK S M, CROCKER L D, MERRITT V C, et al. Independent and synergistic associations between TBI characteristicsand PTSD symptom clusters on cognitive performance and postconcussive symptoms in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans [J].The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 2021, 33(2): 98–108. DOI: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.20050128.

[18]LUCKE-WOLD B P, TURNER R C, LOGSDON A F, et al. Linking traumatic brain injury to chronic traumaticencephalopathy: identification of potential mechanisms leading to neurofibrillary tangle development [J]. Journal ofNeurotrauma, 2014, 31(13): 1129–1138. DOI: 10.1089/neu.2013.3303.

[19]GOLDSTEIN L E, FISHER A M, TAGGE C A, et al. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in blast-exposed military veteransand a blast neurotrauma mouse model [J]. Science Translational Medicine, 2012, 4(134): 134ra60. DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003716.

[20]PRIEMER D S, IACONO D, RHODES C H, et al. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in the brains of military personnel [J].New England Journal of Medicine, 2022, 386(23): 2169–2177. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2203199.

[21]HENION A K, WANG C P, AMUAN M, et al. Role of deployment history on the association between epilepsy andtraumatic brain injury in post-9/11 era US veterans [J]. Neurology, 2023, 101(24): e2571–e2584. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000207943.

[22]康越, 马天, 黄献聪, 等. 颅脑爆炸伤数值模拟研究进展: 建模、力学机制及防护 [J]. 爆炸与冲击, 2023, 43(6): 061101.DOI: 10.11883/bzycj-2022-0521.

KANG Y, MA T, HUANG X C, et al. Advances in numerical simulation of blast-induced traumatic brain injury: modeling,mechanical mechanism and protection [J]. Explosion and Shock Waves, 2023, 43(6): 061101. DOI: 10.11883/bzycj-2022-0521.

[23]FIEVISOHN E, BAILEY Z, GUETTLER A, et al. Primary blast brain injury mechanisms: current knowledge, limitations,and future directions [J]. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering, 2018, 140(2): 020806. DOI: 10.1115/1.4038710.

[24]DU Z B, LI Z J, WANG P, et al. Revealing the effect of skull deformation on intracranial pressure variation during the directinteraction between blast wave and surrogate head [J]. Annals of Biomedical Engineering, 2022, 50(9): 1038–1052. DOI:10.1007/s10439-022-02982-5.

[25]COURTNEY A C, COURTNEY M W. A thoracic mechanism of mild traumatic brain injury due to blast pressure waves [J].Medical Hypotheses, 2009, 72(1): 76–83. DOI: 10.1016/j.mehy.2008.08.015.

[26]柳占立, 杜智博, 张家瑞, 等. 颅脑爆炸伤致伤机制及防护研究进展 [J]. 爆炸与冲击, 2022, 42(4): 041101. DOI:10.11883/bzycj-2021-0053.

LIU Z L, DU Z B, ZHANG J R, et al. Progress in the mechanism and protection of blast-induced traumatic brain injury [J].Explosion and Shock Waves, 2022, 42(4): 041101. DOI: 10.11883/bzycj-2021-0053.

[27]BAILEY Z S, HUBBARD W B, VANDEVORD P J. Cellular mechanisms and behavioral outcomes in blast-inducedneurotrauma: comparing experimental setups [M]//KOBEISSY F H, DIXON C E, HAYES R L, et al. Injury Models of theCentral Nervous System: Methods and Protocols. New York: Springer, 2016: 119–138. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3816-2_8.

[28]吴育寿, 柴家科. 脑冲击伤致伤机制和临床前治疗的研究进展 [J]. 中华创伤杂志, 2020, 36(5): 470–474. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-8050.2020.05.014.

WU Y S, CHAI J K. Research progress in mechanism and preclinical treatment for blast traumatic brain injury [J]. ChineseJournal of Trauma, 2020, 36(5): 470–474. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-8050.2020.05.014.

[29]ZIEBELL J M, MORGANTI-KOSSMANN M C. Involvement of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines inthe pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury [J]. Neurotherapeutics, 2010, 7(1): 22–30. DOI: 10.1016/j.nurt.2009.10.016.

[30]PITT J, PITT Y, LOCKWICH J. Clinical and cellular aspects of traumatic brain injury [M]//GUPTA R C. Handbook ofToxicology of Chemical Warfare Agents. 3rd ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2020: 745–765. DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-12-819090-6.00044-1.

[31]NONAKA M, TAYLOR W W, BUKALO O, et al. Behavioral and myelin-related abnormalities after blast-induced mildtraumatic brain injury in mice [J]. Journal of Neurotrauma, 2021, 38(11): 1551–1571. DOI: 10.1089/neu.2020.7254.

[32]ARMSTRONG R C, SULLIVAN G M, PERL D P, et al. White matter damage and degeneration in traumatic brain injury [J].Trends in Neurosciences, 2024, 47(9): 677–692. DOI: 10.1016/j.tins.2024.07.003.

[33]GUEDES V A, KENNEY K, SHAHIM P, et al. Exosomal neurofilament light [J]. Neurology, 2020, 94(23): e2412–e2423.DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009577.

[34]HILL C S, COLEMAN M P, MENON D K. Traumatic axonal injury: mechanisms and translational opportunities [J]. Trendsin Neurosciences, 2016, 39(5): 311–324. DOI: 10.1016/j.tins.2016.03.002.

[35]JAGODA A, PRABHU A, RIGGIO S. Behavioral and neurocognitive sequelae of concussion in the emergency department [M]//ZUN L S, NORDSTROM K, WILSON M P. Behavioral Emergencies for Healthcare Providers. Cham: Springer, 2021: 341–355. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-030-52520-0_35.

[36]KRIEG J L, LEONARD A V, TURNER R J, et al. Identifying the phenotypes of diffuse axonal injury following traumaticbrain injury [J]. Brain Sciences, 2023, 13(11): 1607. DOI: 10.3390/brainsci13111607.

[37]JOHNSON V E, STEWART W, SMITH D H. Axonal pathology in traumatic brain injury [J]. Experimental Neurology,2013, 246: 35–43. DOI: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.01.013.

[38]FEHILY B, FITZGERALD M. Repeated mild traumatic brain injury: potential mechanisms of damage [J]. CellTransplantation, 2017, 26(7): 1131–1155. DOI: 10.1177/0963689717714092.

[39]POZO DEVOTO V M, LACOVICH V, FEOLE M, et al. Unraveling axonal mechanisms of traumatic brain injury [J]. ActaNeuropathologica Communications, 2022, 10(1): 140. DOI: 10.1186/s40478-022-01414-8.

[40]CHEN Y, GU M, PATTERSON J, et al. Temporal alterations in cerebrovascular glycocalyx and cerebral blood flow afterexposure to a high-intensity blast in rats [J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2024, 25(7): 3580. DOI: 10.3390/ijms25073580.

[41]MCKEE A C, ROBINSON M E. Military-related traumatic brain injury and neurodegeneration [J]. Alzheimer’s amp; Dementia,2014, 10(3S): S242–S253. DOI: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.04.003.

[42]TAGGE C A, FISHER A M, MINAEVA O V, et al. Concussion, microvascular injury, and early tauopathy in young athletesafter impact head injury and an impact concussion mouse model [J]. Brain, 2018, 141(2): 422–458. DOI: 10.1093/brain/awx350.

[43]ELDER G A, GAMA SOSA M A, DE [43] GASPERI R, et al. The neurovascular unit as a locus of injury in low-level blast-induced neurotrauma [J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2024, 25(2): 1150. DOI: 10.3390/ijms25021150.[44]ELDER G A, GAMA SOSA M A, DE GASPERI R, et al. Vascular and inflammatory factors in the pathophysiology of blastinducedbrain injury [J]. Frontiers in Neurology, 2015, 6: 48. DOI: 10.3389/fneur.2015.00048.

[45]GAMA SOSA M A, DE GASPERI R, PRYOR D, et al. Low-level blast exposure induces chronic vascular remodeling,perivascular astrocytic degeneration and vascular-associated neuroinflammation [J]. Acta Neuropathologica Communications,2021, 9(1): 167. DOI: 10.1186/s40478-021-01269-5.

[46]MEABON J S, COOK D G, YAGI M, et al. Chronic elevation of plasma vascular endothelial growth factor-a (VEGF-A) isassociated with a history of blast exposure [J]. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 2020, 417: 117049. DOI: 10.1016/j.jns.2020.117049.

[47]WANG Y, WEI Y L, REN M, et al. Blast exposure alters synaptic connectivity in the mouse auditory cortex [J]. Journal ofNeurotrauma, 2024, 41(11/12): 1438–1449. DOI: 10.1089/neu.2023.0348.

[48]RATLIFF W A, MERVIS R F, CITRON B A, et al. Effect of mild blast-induced TBI on dendritic architecture of the cortexand hippocampus in the mouse [J]. Scientific Reports, 2020, 10(1): 2206. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-020-59252-4.

[49]KONAN L M, SONG H L, PENTECOST G, et al. Multi-focal neuronal ultrastructural abnormalities and synaptic alterationsin mice after low-intensity blast exposure [J]. Journal of Neurotrauma, 2019, 36(13): 2117–2128. DOI: 10.1089/neu.2018.6260.

[50]VOGEL Ⅲ E W, RWEMA S H, MEANEY D F, et al. Primary blast injury depressed hippocampal long-term potentiationthrough disruption of synaptic proteins [J]. Journal of Neurotrauma, 2017, 34(5): 1063–1073. DOI: 10.1089/neu.2016.4578.

[51]VOGEL E W, EFFGEN G B, PATEL T P, et al. Isolated primary blast inhibits long-term potentiation in organotypichippocampal slice cultures [J]. Journal of Neurotrauma, 2016, 33(7): 652–661. DOI: 10.1089/neu.2015.4045.

[52]ALMEIDA M F, PIEHLER T, CARSTENS K E, et al. Distinct and dementia-related synaptopathy in the hippocampus aftermilitary blast exposures [J]. Brain Pathology, 2021, 31(3): e12936. DOI: 10.1111/bpa.12936.

[53]JAMJOOM A A B, RHODES J, ANDREWS P J D, et al. The synapse in traumatic brain injury [J]. Brain, 2021, 144(1):18–31. DOI: 10.1093/brain/awaa321.

[54]KAPLAN G B, LEITE-MORRIS K A, WANG L, et al. Pathophysiological bases of comorbidity: traumatic brain injury andpost-traumatic stress disorder [J]. Journal of Neurotrauma, 2018, 35(2): 210–225. DOI: 10.1089/neu.2016.4953.

[55]CHEN S Y, SIEDHOFF H R, ZHANG H, et al. Low-intensity blast induces acute glutamatergic hyperexcitability in mousehippocampus leading to long-term learning deficits and altered expression of proteins involved in synaptic plasticity andserine protease inhibitors [J]. Neurobiology of Disease, 2022, 165: 105634. DOI: 10.1016/j.nbd.2022.105634.

[56]ORR T J, LESHA E, KRAMER A H, et al. Traumatic brain injury: a comprehensive review of biomechanics and molecularpathophysiology [J]. World Neurosurgery, 2024, 185: 74–88. DOI: 10.1016/j.wneu.2024.01.084.

[57]BUTLER T R, SELF R L, SMITH K J, et al. Selective vulnerability of hippocampal cornu ammonis 1 pyramidal cells toexcitotoxic insult is associated with the expression of polyamine-sensitive N-methyl-d-asparate-type glutamate receptors [J].Neuroscience, 2010, 165(2): 525–534. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.10.018.

[58]刘子华, 胡博玄. 颅脑损伤后血脑屏障的损伤机制与检测方法新进展 [J]. 中国临床神经外科杂志, 2022, 27(3): 214–217.DOI: 10.13798/j.issn.1009-153X.2022.03.021.

[59]BHOWMICK S, D’MELLO V, CARUSO D, et al. Impairment of pericyte-endothelium crosstalk leads to blood-brain barrierdysfunction following traumatic brain injury [J]. Experimental Neurology, 2019, 317: 260–270. DOI: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2019.03.014.

[60]MICHINAGA S, KOYAMA Y. Pathophysiological responses and roles of astrocytes in traumatic brain injury [J].International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2021, 22(12): 6418. DOI: 10.3390/ijms22126418.

[61]READNOWER R D, CHAVKO M, ADEEB S, et al. Increase in blood-brain barrier permeability, oxidative stress, andactivated microglia in a rat model of blast-induced traumatic brain injury [J]. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 2010,88(16): 3530–3539. DOI: 10.1002/jnr.22510.

[62]DADGOSTAR E, RAHIMI S, NIKMANZAR S, et al. Aquaporin 4 in traumatic brain injury: from molecular pathways totherapeutic target [J]. Neurochemical Research, 2022, 47(4): 860–871. DOI: 10.1007/s11064-021-03512-w.

[63]PUHAKKA N, DAS GUPTA S, LESKINEN S, et al. Proteomics of deep cervical lymph nodes after experimental traumaticbrain injury [J]. Neurotrauma Reports, 2023, 4(1): 359–366. DOI: 10.1089/neur.2023.0008.

[64]BOLTE [64] A C, DUTTA A B, HURT M E, et al. Meningeal lymphatic dysfunction exacerbates traumatic brain injury pathogenesis [J]. Nature Communications, 2020, 11(1): 4524. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-020-18113-4.

[65]FREEDMAN M S, GNANAPAVAN S, BOOTH R A, et al. Guidance for use of neurofilament light chain as a cerebrospinalfluid and blood biomarker in multiple sclerosis management [J]. eBioMedicine, 2024, 101: 104970. DOI: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2024.104970.

[66]LIAO J W, ZHANG M C, SHI Z C, et al. Improving the function of meningeal lymphatic vessels to promote brain edemaabsorption after traumatic brain injury [J]. Journal of Neurotrauma, 2023, 40(3/4): 383–394. DOI: 10.1089/neu.2022.0150.

[67]BRAUN M, SEVAO M, KEIL S A, et al. Macroscopic changes in aquaporin-4 underlie blast traumatic brain injury-relatedimpairment in glymphatic function [J]. Brain, 2024, 147(6): 2214–2229. DOI: 10.1093/brain/awae065.

[68]TARASOFF-CONWAY J M, CARARE R O, OSORIO R S, et al. Clearance systems in the brain: implications for alzheimerdisease [J]. Nature Reviews Neurology, 2015, 11(8): 457–470. DOI: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.119.

[69]LEVITES Y, DAMMER E B, RAN Y, et al. Integrative proteomics identifies a conserved Aβ amyloid responsome, novelplaque proteins, and pathology modifiers in Alzheimer’s disease [J]. Cell Reports Medicine, 2024, 5(8): 101669. DOI:10.1016/j.xcrm.2024.101669.

[70]SIMON D W, MCGEACHY M J, BAYIR H, et al. The far-reaching scope of neuroinflammation after traumatic braininjury [J]. Nature Reviews Neurology, 2017, 13(3): 171–191. DOI: 10.1038/nrneurol.2017.13.

[71]MCKEE C A, LUKENS J R. Emerging roles for the immune system in traumatic brain injury [J]. Frontiers in Immunology,2016, 7: 556. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00556.

[72]CORPS K N, ROTH T L, MCGAVERN D B. Inflammation and neuroprotection in traumatic brain injury [J]. JAMANeurology, 2015, 72(3): 355–362. DOI: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.3558.

[73]GUILHAUME-CORREA F, PICKRELL A M, VANDEVORD P J. The imbalance of astrocytic mitochondrial dynamicsfollowing blast-induced traumatic brain injury [J]. Biomedicines, 2023, 11(2): 329. DOI: 10.3390/biomedicines11020329.

[74]SHIVELY S B, HORKAYNE-SZAKALY I, JONES R V, et al. Characterisation of interface astroglial scarring in the humanbrain after blast exposure: a post-mortem case series [J]. The Lancet Neurology, 2016, 15(9): 944–953. DOI: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30057-6.

[75]LIER J, ONDRUSCHKA B, BECHMANN I, et al. Fast microglial activation after severe traumatic brain injuries [J].International Journal of Legal Medicine, 2020, 134(6): 2187–2193. DOI: 10.1007/s00414-020-02308-x.

[76]RAMLACKHANSINGH A F, BROOKS D J, GREENWOOD R J, et al. Inflammation after trauma: microglial activation andtraumatic brain injury [J]. Annals of Neurology, 2011, 70(3): 374–383. DOI: 10.1002/ana.22455.

[77]JOHNSON V E, STEWART J E, BEGBIE F D, et al. Inflammation and white matter degeneration persist for years after asingle traumatic brain injury [J]. Brain, 2013, 136(1): 28–42. DOI: 10.1093/brain/aws322.

[78]SONG H L, CHEN M, CHEN C, et al. Proteomic analysis and biochemical correlates of mitochondrial dysfunction after lowintensityprimary blast exposure [J]. Journal of Neurotrauma, 2019, 36(10): 1591–1605. DOI: 10.1089/neu.2018.6114.

[79]FRATI A, CERRETANI D, FIASCHI A I, et al. Diffuse axonal injury and oxidative stress: a comprehensive review [J].International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2017, 18(12): 2600. DOI: 10.3390/ijms18122600.

[80]FESHARAKI-ZADEH A, DATTA D. An overview of preclinical models of traumatic brain injury (TBI): relevance topathophysiological mechanisms [J]. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 2024, 18: 1371213. DOI: 10.3389/fncel.2024.1371213.

[81]KURIAKOSE M, YOUNGER D, RAVULA A R, et al. Synergistic role of oxidative stress and blood-brain barrierpermeability as injury mechanisms in the acute pathophysiology of blast-induced neurotrauma [J]. Scientific Reports, 2019,9(1): 7717. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-019-44147-w.

[82]FESHARAKI-ZADEH A. Oxidative stress in traumatic brain injury [J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2022,23(21): 13000. DOI: 10.3390/ijms232113000.

[83]ZHANG C N, LIU C, LI F J, et al. Extracellular mitochondria activate microglia and contribute to neuroinflammation intraumatic brain injury [J]. Neurotoxicity Research, 2022, 40(6): 2264–2277. DOI: 10.1007/s12640-022-00566-8.

[84]ALONSO A D, COHEN L S, CORBO C, et al. Hyperphosphorylation of tau associates with changes in its function beyondmicrotubule stability [J]. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 2018, 12: 338. DOI: 10.3389/fncel.2018.00338.

[85]CHEN M, SONG H L, CUI J K, et al. Proteomic profiling of mouse brains exposed to blast-induced mild traumatic braininjury reveals changes in axonal proteins and phosphorylated tau [J]. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 2018, 66(2): 751–773.DOI: 10.3233/JAD-180726.

[86]DICKSTEIN D L, DE GASPERI R, GAMA SOSA M A, et al. Brain and blood biomarkers of tauopathy and neuronal injuryin humans and rats with neurobehavioral syndromes following blast exposure [J]. Molecular Psychiatry, 2021, 26(10):5940–5954. DOI: 10.1038/s41380-020-0674-z.

[87]BUTLER M L M D, DIXON E, STEIN T D, et al. Tau pathology in chronic traumatic encephalopathy is primarilyneuronal [J]. Journal of Neuropathology amp; Experimental Neurology, 2022, 81(10): 773–780. DOI: 10.1093/jnen/nlac065.

[88]KONDO A, SHAHPASAND K, MANNIX R, et al. Antibody against early driver of neurodegeneration cis p-tau blocks braininjury and tauopathy [J]. Nature, 2015, 523(7561): 431–436. DOI: 10.1038/nature14658.

[89]FALCON B, ZIVANOV J, ZHANG W J, et al. Novel tau filament fold in chronic traumatic encephalopathy encloseshydrophobic molecules [J]. Nature, 2019, 568(7752): 420–423. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-019-1026-5.

[90]BOUTTÉ A M, THANGAVELU B, NEMES J, et al. Neurotrauma biomarker levels and adverse symptoms among militaryand law enforcement personnel exposed to occupational overpressure without diagnosed traumatic brain injury [J]. JAMANetwork Open, 2021, 4(4): e216445. DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.6445.

[91]LEIVA-SALINAS C, SINGH A, LAYFIELD E, et al. Early brain amyloid accumulation at PET in military instructorsexposed to subconcussive blast injuries [J]. Radiology, 2023, 307(5): e221608. DOI: 10.1148/radiol.221608.

[92]DEKOSKY S T, BLENNOW K, IKONOMOVIC M D, et al. Acute and chronic traumatic encephalopathies: pathogenesisand biomarkers [J]. Nature Reviews Neurology, 2013, 9(4): 192–200. DOI: 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.36.

[93]MCKEE A C, STEIN T D, NOWINSKI C J, et al. The spectrum of disease in chronic traumatic encephalopathy [J]. Brain,2013, 136(1): 43–64. DOI: 10.1093/brain/aws307.

[94]PEREZ GARCIA G, DE GASPERI R, TSCHIFFELY A E, et al. Repetitive low-level blast exposure improves behavioraldeficits and chronically lowers Aβ42 in an Alzheimer disease transgenic mouse model [J]. Journal of Neurotrauma, 2021,38(22): 3146–3173. DOI: 10.1089/neu.2021.0184.

[95]DE GASPERI R, GAMA SOSA M A, KIM S H, et al. Acute blast injury reduces brain abeta in two rodent species [J].Frontiers in Neurology, 2012, 3: 177. DOI: 10.3389/fneur.2012.00177.

[96]LI G, ILIFF J, SHOFER J, et al. CSF β-amyloid and tau biomarker changes in veterans with mild traumatic brain injury [J].Neurology, 2024, 102(7): e209197. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000209197.

[97]TURK K W, GEADA A, ALVAREZ V E, et al. A comparison between tau and amyloid-β cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers inchronic traumatic encephalopathy and Alzheimer disease [J]. Alzheimer’s Research amp; Therapy, 2022, 14(1): 28. DOI:10.1186/s13195-022-00976-y.

[98]SUGARMAN M A, MCKEE A C, STEIN T D, et al. Failure to detect an association between self-reported traumatic braininjury and Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology and dementia [J]. Alzheimer’s amp; Dementia, 2019, 15(5): 686–698. DOI:10.1016/j.jalz.2018.12.015.

[99]WEINER M W, HARVEY D, LANDAU S M, et al. Traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic stress disorder are notassociated with Alzheimer’s disease pathology measured with biomarkers [J]. Alzheimer’s amp; Dementia, 2023, 19(3): 884–895. DOI: 10.1002/alz.12712.

[100]ASHWORTH E R, BAXTER D, GIBB I E. Blast traumatic brain injury [M]//BULL A M J, CLASPER J, MAHONEY P F.Blast Injury Science and Engineering. Cham: Springer, 2022: 231-236. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-031-10355-1_22.

[101]GAVETT B E, CANTU R C, SHENTON M, et al. Clinical appraisal of chronic traumatic encephalopathy: currentperspectives and future directions [J]. Current Opinion in Neurology, 2011, 24(6): 525–531. DOI: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32834cd477.

[102]RANZENBERGER L R, DAS J M, SNYDER T. Diffusion tensor imaging [M/OL]//StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL):StatPearls Publishing, 2024[2024-05-21]. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537361/.

[103]GRANT M, LIU J J, WINTERMARK M, et al. Current state of diffusion-weighted imaging and diffusion tensor imaging fortraumatic brain injury prognostication [J]. Neuroimaging Clinics of North America, 2023, 33(2): 279–297. DOI: 10.1016/j.nic.2023.01.004.

[104]JORGE R E, ACION L, WHITE T, et al. White matter abnormalities in veterans with mild traumatic brain injury [J].American Journal of Psychiatry, 2012, 169(12): 1284–1291. DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12050600.

[105]STONE J R, AVANTS B B, TUSTISON N J, et al. Functional and structural neuroimaging correlates of repetitive low-levelblast exposure in career breachers [J]. Journal of Neurotrauma, 2020, 37(23): 2468–2481. DOI: 10.1089/neu.2020.7141.

[106]PINTO [106] M S, WINZECK S, KORNAROPOULOS E N, et al. Use of support vector machines approach via combat harmonized diffusion tensor imaging for the diagnosis and prognosis of mild traumatic brain injury: a CENTER-TBIstudy [J]. Journal of Neurotrauma, 2023, 40(13/14): 1317–1338. DOI: 10.1089/neu.2022.0365.

[107]GRAHAM N S N, JOLLY A, ZIMMERMAN K, et al. Diffuse axonal injury predicts neurodegeneration aftermoderate–severe traumatic brain injury [J]. Brain, 2020, 143(12): 3685–3698. DOI: 10.1093/brain/awaa316.

[108]AGOSTON D V, KAMNAKSH A. Modeling the neurobehavioral consequences of blast-induced traumatic brain injuryspectrum disorder and identifying related biomarkers [M]//KOBEISSY F H. Brain Neurotrauma: Molecular,Neuropsychological, and Rehabilitation Aspects. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2015.

[109]ZETTERBERG H, BLENNOW K. Fluid biomarkers for mild traumatic brain injury and related conditions [J]. NatureReviews Neurology, 2016, 12(10): 563–574. DOI: 10.1038/nrneurol.2016.127.

[110]ZETTERBERG H, SMITH D H, BLENNOW K. Biomarkers of mild traumatic brain injury in cerebrospinal fluid andblood [J]. Nature Reviews Neurology, 2013, 9(4): 201–210. DOI: 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.9.

[111]GHAITH H S, NAWAR A A, GABRA M D, et al. A literature review of traumatic brain injury biomarkers [J]. MolecularNeurobiology, 2022, 59(7): 4141–4158. DOI: 10.1007/s12035-022-02822-6.

[112]SVETLOV S I, LARNER S F, KIRK D R, et al. Biomarkers of blast-induced neurotrauma: profiling molecular and cellularmechanisms of blast brain injury [J]. Journal of Neurotrauma, 2009, 26(6): 913–921. DOI: 10.1089/neu.2008.0609.

[113]AGOSTON D V, ELSAYED M. Serum-based protein biomarkers in blast-induced traumatic brain injury spectrum disorder [J].Frontiers in Neurology, 2012, 3: 107. DOI: 10.3389/fneur.2012.00107.

[114]BAZARIAN J J, BIBERTHALER P, WELCH R D, et al. Serum GFAP and UCH-L1 for prediction of absence of intracranialinjuries on head CT (ALERT-TBI): a multicentre observational study [J]. The Lancet Neurology, 2018, 17(9): 782–789. DOI:10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30231-X.

[115]TRIVEDI D, FORSSTEN M P, CAO Y, et al. Screening performance of S100 calcium-binding protein B, glial fibrillaryacidic protein, and ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L1 for intracranial injury within six hours of injury and beyond [J]. Journalof Neurotrauma, 2024, 41(3/4): 349–358. DOI: 10.1089/neu.2023.0322.

[116]CARR W, YARNELL A M, ONG R, et al. Ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase-L1 as a serum neurotrauma biomarker forexposure to occupational low-level blast [J]. Frontiers in Neurology, 2015, 6: 49. DOI: 10.3389/fneur.2015.00049.

[117]BOUTTÉ A M, THANGAVELU B, LAVALLE C R, et al. Brain-related proteins as serum biomarkers of acute,subconcussive blast overpressure exposure: a cohort study of military personnel [J]. PLoS One, 2019, 14(8): e0221036. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0221036.

[118]KOCIK V I, DENGLER B A, RIZZO J A, et al. A narrative review of existing and developing biomarkers in acute traumaticbrain injury for potential military deployed use [J]. Military Medicine, 2024, 189(5/6): e1374–e1380. DOI: 10.1093/milmed/usad433.

[119]KORLEY F K, JAIN S, SUN X Y, et al. Prognostic value of day-of-injury plasma GFAP and UCH-L1 concentrations forpredicting functional recovery after traumatic brain injury in patients from the US TRACK-TBI cohort: an observationalcohort study [J]. The Lancet Neurology, 2022, 21(9): 803–813. DOI: 10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00256-3.

[120]HELMRICH I R A R, CZEITER E, AMREIN K, et al. Incremental prognostic value of acute serum biomarkers forfunctional outcome after traumatic brain injury (CENTER-TBI): an observational cohort study [J]. The Lancet Neurology,2022, 21(9): 792–802. DOI: 10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00218-6.

[121]PUCCIO A M, YUE J K, KORLEY F K, et al. Diagnostic utility of glial fibrillary acidic protein beyond 12 hours aftertraumatic brain injury: a TRACK-TBI study [J]. Journal of Neurotrauma, 2024, 41(11/12): 1353–1363. DOI: 10.1089/neu.2023.0186.

[122]BÖHMER A E, OSES J P, SCHMIDT A P, et al. Neuron-specific enolase, S100B, and glial fibrillary acidic protein levels asoutcome predictors in patients with severe traumatic brain injury [J]. Neurosurgery, 2011, 68(6): 1624–1631. DOI: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318214a81f.

[123]POWELL J R, BOLTZ A J, DECICCO J P, et al. Neuroinflammatory biomarkers associated with mild traumatic brain injuryhistory in special operations forces combat soldiers [J]. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 2020, 35(5): 300–307. DOI:10.1097/HTR.0000000000000598.

[124]MERCIER E, TARDIF P A, CAMERON P A, et al. Prognostic value of neuron-specific enolase (NSE) for prediction ofpost-concussion symptoms following a mild traumatic brain injury: a systematic review [J]. Brain Injury, 2018, 32(1): 29–40.DOI: 10.1080/02699052.2017.1385097.

[125]MERCIER E, BOUTIN A, SHEMILT M, et al. Predictive value of neuron-specific enolase for prognosis in patients withmoderate or severe traumatic brain injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis [J]. Canadian Medical Association OpenAccess Journal, 2016, 4(3): E371–E382. DOI: 10.9778/cmajo.20150061.

[126]RICHTER S, WINZECK S, CZEITER E, et al. Serum biomarkers identify critically ill traumatic brain injury patients forMRI [J]. Critical Care, 2022, 26(1): 369. DOI: 10.1186/s13054-022-04250-3.

[127]CLARKE G J B, FOLLESTAD T, SKANDSEN T, et al. Chronic immunosuppression across 12 months and high ability ofacute and subacute CNS-injury biomarker concentrations to identify individuals with complicated mTBI on acute CT andMRI [J]. Journal of Neuroinflammation, 2024, 21(1): 109. DOI: 10.1186/s12974-024-03094-8.

[128]SHAHIM P, POLITIS A, VAN DER MERWE A, et al. Neurofilament light as a biomarker in traumatic brain injury [J].Neurology, 2020, 95(6): e610–e622. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009983.

[129]VORN R, NAUNHEIM R, LAI C, et al. Elevated axonal protein markers following repetitive blast exposure in militarypersonnel [J]. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 2022, 16: 853616. DOI: 10.3389/fnins.2022.853616.

[130]GRAHAM N S N, ZIMMERMAN K A, MORO F, et al. Axonal marker neurofilament light predicts long-term outcomes andprogressive neurodegeneration after traumatic brain injury [J]. Science Translational Medicine, 2021, 13(613): eabg9922.DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abg9922.

[131]SHAHIM P, PHAM D L, VAN DER MERWE A J, et al. Serum NFL and GFAP as biomarkers of progressiveneurodegeneration in TBI [J]. Alzheimer’s amp; Dementia, 2024, 20(7): 4663–4676. DOI: 10.1002/alz.13898.

[132]HALICKI M J, HIND K, CHAZOT P L. Blood-based biomarkers in the diagnosis of chronic traumatic encephalopathy:research to date and future directions [J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2023, 24(16): 12556. DOI: 10.3390/ijms241612556.

[133]RUBENSTEIN R, CHANG B G, YUE J K, et al. Comparing plasma phospho tau, total tau, and phospho tau-total tau ratioas acute and chronic traumatic brain injury biomarkers [J]. JAMA Neurology, 2017, 74(9): 1063–1072. DOI: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.0655.

[134]LANGE R T, LIPPA S, BRICKELL T A, et al. Serum tau, neurofilament light chain, glial fibrillary acidic protein, andubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase L1 are associated with the chronic deterioration of neurobehavioral symptoms aftertraumatic brain injury [J]. Journal of Neurotrauma, 2023, 40(5/6): 482–492. DOI: 10.1089/neu.2022.0249.

[135]SHI H, HU X M, LEAK R K, et al. Demyelination as a rational therapeutic target for ischemic or traumatic brain injury [J].Experimental Neurology, 2015, 272: 17–25. DOI: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.03.017.

[136]MEHTA T, FAYYAZ M, GILER G E, et al. Current trends in biomarkers for traumatic brain injury [J]. Open Access Journalof Neurology amp; Neurosurgery, 2020, 12(4): 86–94.

[137]KIM H J, TSAO J W, STANFILL A G. The current state of biomarkers of mild traumatic brain injury [J]. JCI Insight, 2018,3(1): e97105. DOI: 10.1172/jci.insight.97105.

[138]JETER C B, HERGENROEDER G W, HYLIN M J, et al. Biomarkers for the diagnosis and prognosis of mild traumatic braininjury/concussion [J]. Journal of Neurotrauma, 2013, 30(8): 657–670. DOI: 10.1089/neu.2012.2439.

[139]SHANG Y J, WANG Y X, GUO Y D, et al. Analysis of the risk of traumatic brain injury and evaluation neurogranin andmyelin basic protein as potential biomarkers of traumatic brain injury in postmortem examination [J]. Forensic Science,Medicine and Pathology, 2022, 18(3): 288–298. DOI: 10.1007/s12024-022-00459-4.

[140]BOHNERT S, WIRTH C, SCHMITZ W, et al. Myelin basic protein and neurofilament h in postmortem cerebrospinal fluidas surrogate markers of fatal traumatic brain injury [J]. International Journal of Legal Medicine, 2021, 135(4): 1525–1535.DOI: 10.1007/s00414-021-02606-y.

[141]LIU Z T, LIU C W, MA K G. Retrospective study on the correlation between serum MIF level and the condition andprognosis of patients with traumatic head injury [J]. PeerJ, 2023, 11: e15933. DOI: 10.7717/peerj.15933.

[142]ABDELHAK A, FOSCHI M, ABU-RUMEILEH S, et al. Blood GFAP as an emerging biomarker in brain and spinal corddisorders [J]. Nature Reviews Neurology, 2022, 18(3): 158–172. DOI: 10.1038/s41582-021-00616-3.

[143]MENDITTO V G, MORETTI M, BABINI L, et al. Minor head injury in anticoagulated patients: performance of biomarkersS100B, NSE, GFAP, UCH-L1 and alinity TBI in the detection of intracranial injury. a prospective observational study [J].Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine, 2024, 62(7): 1376–1382. DOI: 10.1515/cclm-2023-1169.

[144]GIL-JARDINÉ C, PAYEN J F, BERNARD R, et al. Management of patients suffering from mild traumatic brain injury2023 [J]. Anaesthesia Critical Care amp; Pain Medicine, 2023, 42(4): 101260. DOI: 10.1016/j.accpm.2023.101260.

[145]TSCHIFFELY A E, STATZ J K, EDWARDS K A, et al. Assessing a blast-related biomarker in an operational community:glial fibrillary acidic protein in experienced breachers [J]. Journal of Neurotrauma, 2020, 37(8): 1091–1096. DOI: 10.1089/neu.2019.6512.

[146]THANGAVELU B, LAVALLE C R, EGNOTO M J, et al. Overpressure exposure from 50-caliber rifle training is associatedwith increased amyloid beta peptides in serum [J]. Frontiers in Neurology, 2020, 11: 620. DOI: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00620.

[147]PIERCE M E, HAYES J, HUBER B R, et al. Plasma biomarkers associated with deployment trauma and its consequences inpost-9/11 era veterans: initial findings from the TRACTS longitudinal cohort [J]. Translational Psychiatry, 2022, 12(1): 80.DOI: 10.1038/s41398-022-01853-w.

[148]TOMPKINS P, TESIRAM Y, LERNER M, et al. Brain injury: neuro-inflammation, cognitive deficit, and magneticresonance imaging in a model of blast induced traumatic brain injury [J]. Journal of Neurotrauma, 2013, 30(22): 1888–1897.DOI: 10.1089/neu.2012.2674.

[149]KAWAUCHI S, KONO A, MURAMATSU Y, et al. Meningeal damage and interface astroglial scarring in the rat brainexposed to a laser-induced shock wave(s) [J]. Journal of Neurotrauma, 2024, 41(15/16): e2039–e2053. DOI: 10.1089/neu.2023.0572.

[150]SAJJA V S S S, HUBBARD W B, HALL C S, et al. Enduring deficits in memory and neuronal pathology after blast-inducedtraumatic brain injury [J]. Scientific Reports, 2015, 5(1): 15075. DOI: 10.1038/srep15075.

[151]UNDÉN J, INGEBRIGTSEN T, ROMNER B, et al. Scandinavian guidelines for initial management of minimal, mild andmoderate head injuries in adults: an evidence and consensus-based update [J]. BMC Medicine, 2013, 11: 50. DOI: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-50.

[152]ORIS C, KAHOUADJI S, BOUVIER D, et al. Blood biomarkers for the management of mild traumatic brain injury inclinical practice [J]. Clinical Chemistry, 2024, 70(8): 1023–1036. DOI: 10.1093/clinchem/hvae049.

[153]UNDÉN J, ROMNER B. A new objective method for CT triage after minor head injury-serum S100B [J]. ScandinavianJournal of Clinical and Laboratory Investigation, 2009, 69(1): 13–17. DOI: 10.1080/00365510802651833.

[154]刘宇晨. 细胞外囊泡的生物学功能及其作为体内小核糖核酸药物递送载体的研究 [D]. 南京: 南京大学, 2016: 10–16.

LIU Y C. The biological functions of extracellular vesicle and its utilization as small RNA carrier in vivo [D]. Nanjing:Nanjing University, 2016: 10–16.

[155]FLYNN S, LEETE J, SHAHIM P, et al. Extracellular vesicle concentrations of glial fibrillary acidic protein andneurofilament light measured 1 year after traumatic brain injury [J]. Scientific Reports, 2021, 11(1): 3896. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-021-82875-0.

[156]SCHINDLER C R, HÖRAUF J A, WEBER B, et al. Identification of novel blood-based extracellular vesicles biomarkercandidates with potential specificity for traumatic brain injury in polytrauma patients [J]. Frontiers in Immunology, 2024, 15:1347767. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1347767.

[157]XU X J, GE Q Q, YANG M S, et al. Neutrophil-derived interleukin-17A participates in neuroinflammation induced bytraumatic brain injury [J]. Neural Regeneration Research, 2023, 18(5): 1046–1051. DOI: 10.4103/1673-5374.355767.

[158]HUANG X T, XU X J, WANG C, et al. Using bioinformatics technology to mine the expression of serum exosomal miRNAin patients with traumatic brain injury [J]. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 2023, 17: 1145307. DOI: 10.3389/fnins.2023.1145307.

[159]REDELL J B, MOORE A N, WARD N H, et al. Human traumatic brain injury alters plasma microrna levels [J]. Journal ofNeurotrauma, 2010, 27(12): 2147–2156. DOI: 10.1089/neu.2010.1481.

[160]DI PIETRO V, RAGUSA M, DAVIES D, et al. MicroRNAs as novel biomarkers for the diagnosis and prognosis of mild andsevere traumatic brain injury [J]. Journal of Neurotrauma, 2017, 34(11): 1948–1956. DOI: 10.1089/neu.2016.4857.

[161]YANG Y J, WANG Y, LI P P, et al. Serum exosomes miR-206 and miR-549a-3p as potential biomarkers of traumatic braininjury [J]. Scientific Reports, 2024, 14(1): 10082. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-024-60827-8.

[162]JOHNSON J J, LOEFFERT A C, STOKES J, et al. Association of salivary microrna changes with prolonged concussionsymptoms [J]. JAMA Pediatrics, 2018, 172(1): 65–73. DOI: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.3884.

[163]BHOMIA M, BALAKATHIRESAN N S, WANG K K, et al. A panel of serum miRNA biomarkers for the diagnosis ofsevere to mild traumatic brain injury in humans [J]. Scientific Reports, 2016, 6(1): 28148. DOI: 10.1038/srep28148.

[164]TAHERI S, TANRIVERDI F, ZARARSIZ G, et al. Circulating microRNAs as potential biomarkers for traumatic braininjury-induced hypopituitarism [J]. Journal of Neurotrauma, 2016, 33(20): 1818–1825. DOI: 10.1089/neu.2015.4281.

(责任编辑 张凌云)

基金项目: 军队高层次科技创新人才自主科研项目