Case observation of viral keratitis caused by SARS-CoV-2

Xie Mengzhen,2, Zhang Hao,2, Ma Ke, Yin Hongbo, Wang Lixiang, Tang Jing

Abstract

•AIM: To report three cases of viral keratitis caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).

•METHODS: Slit lamp, intraocular pressure, corneal fluorescence staining, anterior segment photography, in vivo confocal microscopy (IVCM), and routine fundus screening were performed in the three confirmed patients. Treatment involved Ganciclovir, artificial tears and glucocorticoid eye drops.

•RESULTS: Three patients with SARS-CoV-2 keratitis (SCK) recovered well after standard treatment.

•CONCLUSION: SARS-CoV-2 keratitis typically presents as corneal subepithelial infiltration and can result in a decrease in corneal subepithelial nerve fiber density and an increase in dendritic cells (DC). Antiviral therapy in combination with glucocorticoid has proven to be effective.

•KEYWORDS:keratitis; COVID-19; SARS-CoV-2; Ganciclovir

INTRODUCTION

COVID-19 is caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)[1]. Globally, as of 5:07 p.m. CET, 13 January 2023, there have been 661 545 258 confirmed cases of COVID-19, including 6 700 519 deaths, reported to WHO (www.who.int). The most commonly recognized route of transmission is through respiratory transmission[2], but recent studies have suggested that contact with eyes, specifically tears and conjunctival secretions, may also lead to transmission[3-4]. All corona viruses are positive-sense single-stranded RNA viruses that use RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) to replicate their genomes[5]. The most common ocular symptom of COVID-19 infection is conjunctivitis, with incidence ranging from 0.8% to 32% according to previous studies and meta-analyses[6-7]. SARS-CoV-2 can also cause visual perception impaired[8], retinal detachment, retinitis, optic neuritis, meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) and other ocular surface disorders[9], but there are relatively few reports on keratitis.

Conjunctival and corneal epithelial cells express angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and trans-membrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2) specific SARS-CoV-2 receptors[10]. After the viral spike protein binds to ACE2, TMPRSS2 plays an important role in facilitating cell entry of SARS-CoV-2[11-13]. At present, there are not many SARS-CoV-2 keratitis (SCK), and there is no recognized treatment plan. Therefore, we reported three cases of the SCK and medication plan, and all patients had good prognosis. Hope to provide ophthalmologists around the world with certain treatment experience.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

EthicalStatementThe study protocol was approved by the West China Hospital, Sichuan University, and in accordance with the tenet of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participating individuals signed the informed consent.

Patient,MedicalExaminationsandTherapies

Casepresentation

Case1 A 32-year-old female had a fever of 42-degree after contracting COVID-19 after receiving two doses of the COVID-19 vaccine for 6 mo (Table 1). On the same day, her right eye began to exhibit redness. The fever subsided 2 d later, but 3 d after the fever, the right eye photophobia appeared, and the visual acuity decreased significantly. The patient visited our clinic 2 wk after the COVID-19 diagnosis, with no relevant medical history. We performed visual acuity, intraocular pressure examination, corneal fluorescence staining, anterior segment photography, macular optical coherence tomography, scanning laser fundus examination. Examinations revealed mild conjunctival congestion in the right eye, corneal edema, point clump changes in the central cornea, and significant staining by corneal fluorescence (Figure 1A-1B). No positive signs in the left eye.

Our treatment regimen consisted of antiviral drugs (Ganciclovir Ophthalmic Gel, Hubei Keyi Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.), corneal repair drugs (20% Deproteinized Calf Blood Extract Eye Gel, SINQI, China), administered four times a day, and corticosteroid hormone (0.1% Fluorometholone Eye Drops, Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Japan) administered three times a day. One week later, the patient returned to the clinic and small patches of opacity were observed in the central cornea of the right eye with scattered punctiform infiltrating foci (Figure 1C-1D), no change in treatment. After 2 wk, a reexamination showed corneal nebula in the central area of the cornea, and no staining was observed by fluorescence staining (Figure 1E-1F). The patient’s vision had returned to normal and intraocular pressure in both eyes was less than 21 mmHg during the course of the disease.

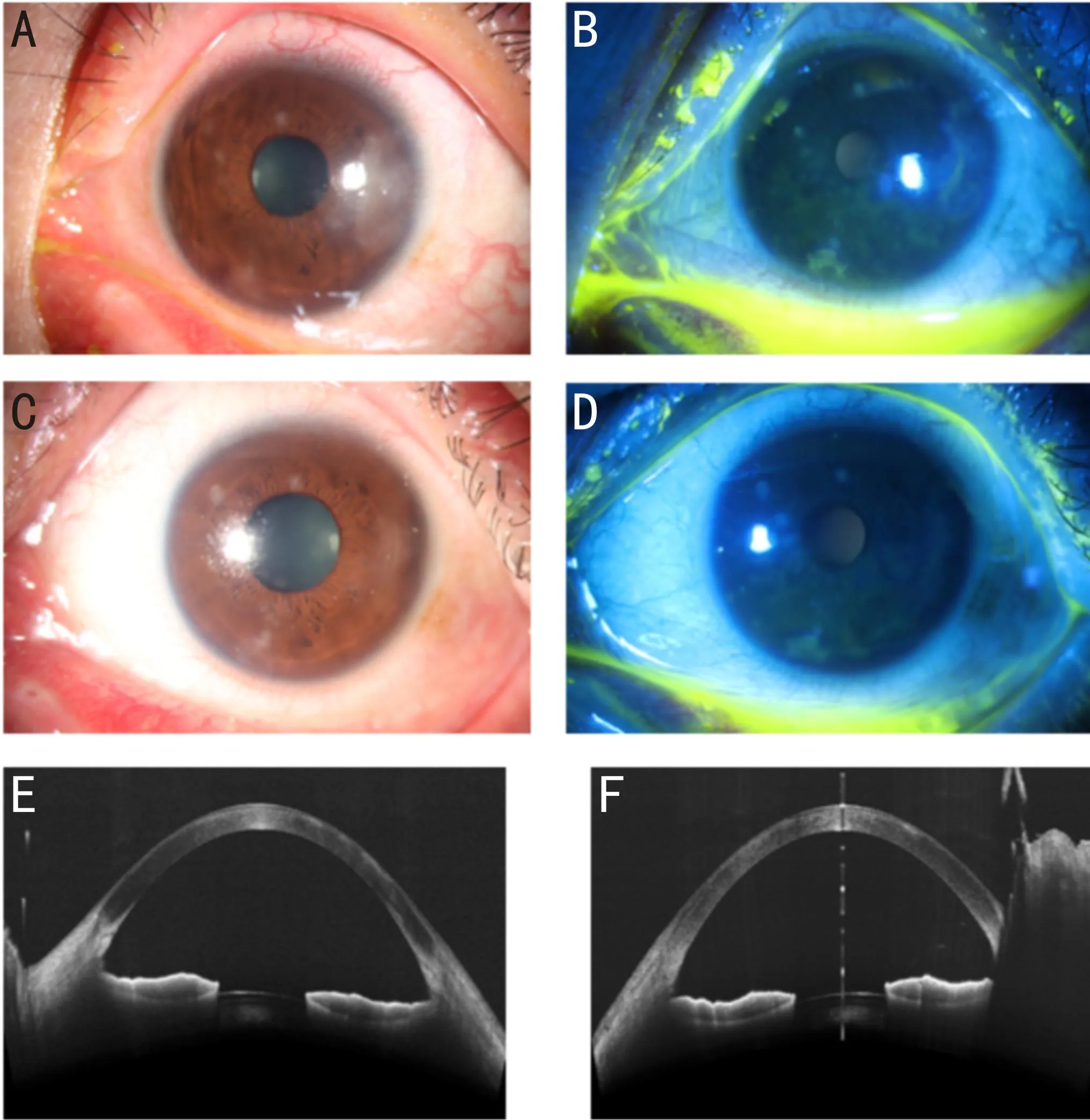

Case2 A male patient, 32 years old, had viral keratitis in the left eye five years ago. The left eye was photophobia and watering 3 d after COVID-19 was diagnosed. It’s important to note that the patient had also received two doses of the COVID-19 vaccine 6 mo prior to these symptoms (Table 1). Two days after the onset of ocular symptoms, the patient was admitted to a grade Ⅲ-a general hospital in Chengdu, Sichuan Province, China. He was initially diagnosed with bacterial keratitis and treated with antibiotics, which did not result in any improvement after 1 wk. He then received antiviral treatment (Ganciclovir Ophthalmic Gel, China) twice a day in another hospital, but self-reported only slight relief of his left eye symptoms. So he was admitted to our hospital after 18 days of photophobia and redness in his left eye. After clinical examination and medical history inquiry, we found conjunctival congestion, subepithelial infiltration of irregular spots in the central and nasal corneas, and corneal macula below the temporal corneas (Figure 2A-2B). As the features of the local lesions in this case were obviously different from those of herpes simplex viral keratitis (HSK) and herpes zoster viral keratitis (HZK), showing scattered spot-like infiltration in one eye, and the spot-like infiltration was obviously larger than adenoviral keratoconjunctivitis (AK), So we diagnosed as SCK. And the treatment plan was the same as in case 1. Similarly, binocular intraocular pressure was less than 21 mmHg throughout the course of the disease. A week later, reexamination revealed diffuse subepithelial infiltration in the left eye, scattered lesions and clear boundaries (Figure 2C-2D). Anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT) results showed that the depth of lesion infiltration in the patient was shallow stroma and the corneal epithelium was intact (Figure 2E-2F). The most prominent feature ofinvivoconfocal microscopy (IVCM) results was the significant reduction in density of subepithelial nerve fibers compared to the contralateral eye, with some activated dendritic cells(DC) present (Figure 3B-3C). Meanwhile, in the left eye, the corneal epithelium had numerous cell fragments and the corneal endothelium had vacuoles (Figure 3A and 3D).

Figure 1 Ophthalmic examination of case 1. A, B) the anterior segment of case 1 was photographed at first visit; C, D) anterior segment photograph during the review one week later; E, F) anterior segment photograph during the review two weeks later.

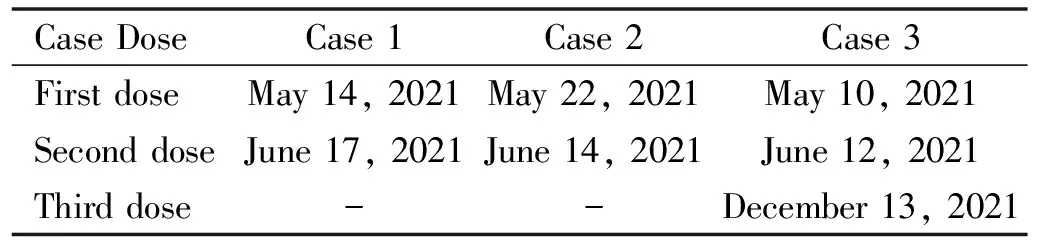

Table 1 The COVID-19 vaccine (Vero cell) vaccination status of the patient

Figure 2 Ophthalmic examination of case 2. A, B) the anterior segment of case 2 was photographed at first visit; C, D) anterior segment photograph during the review one week later; E, F) the result of AS-OCT during the review one week later.

Case3 A 21-year-old female was admitted to our clinic due to experiencing red eyes and photophobia for the past 5 d, at which point she was diagnosed with COVID-19. The patient presented with a visual acuity of 0.5 in her right eye and 0.4 in left eye. Slit lamp examination and corneal fluorescence staining revealed conjunctival hyperemia in both eyes, the central corneal epithelial punctate defect, and central and peripheral corneal subepithelial punctate haze. There were no other abnormalities detected in the anterior eye segments (Figure 4A-4D). SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected in corneal scraping samples from both eyes, leading to the diagnosis of binocular SCK. We initiated treatment by administering topical eye drops, the same protocol as case 1. After one week of follow-up, the patient’s visual acuity had significantly improved, reaching 0.8 in the right eye and 1.0 in the left eye. Slit lamp examination revealed the absence of conjunctival hyperemia in both eyes, the central corneal epithelial punctate defect had healed, with only a few remaining peripheral corneal subepithelial punctate haze spots (Figure 4E-4F). As part of the treatment adjustment, we reduced the frequency of Fluorometholone Eye Drops to twice a day, while maintaining the original usage instructions for the other eye drops. The patient was scheduled for another review after one week of continued medication. The intraocular pressure in both eyes remained below 21 mmHg throughout the course of the disease.

DISCUSSION

There have been few reports on SCK so far, possibly because the incidence of keratitis is lower in the early stages of COVID-19, as shown in Limaetal’s[14]study, which examined 1 740 positive patients and found only four cases keratitis. In addition, these four keratitis patients may be caused by other viral infections such as HSK, HZK, or AK due to reduced systemic immunity caused by COVID-19. Majtanovaetal[15]reported five patients with HSK after COVID-19 infections, demonstrating that SARS-CoV-2 infection may be a risk factor for the occurrence of HSV-1 keratitis. Therefore, during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important to identify the pathogen causing viral keratitis, whether it is herpes simplex virus, herpes zoster virus, Adenovirus, or SARS-CoV-2.

ACE2 and TMPRSS2 are highly expressed in human corneal epithelial cells (HCECs), suggesting that the cornea is a potential route for SARS-CoV-2 transmission[4]. Combined with previous case reports, it is reasonable to believe that SARS-CoV-2 can directly infiltrate the cornea and cause viral keratitis[16-19].

In our three cases, the patients developed ocular symptoms after COVID-19 infection and corneal signs were significantly different from those in previous patients with viral keratitis. The lesions were mainly characterized by corneal subepithelial infiltration as observed during ophthalmic examination, and the infiltration focus did not match completely with the fluorescence stain area. This presentation is quite different from that of common HSK, HZK and AK. HSK and HZK are often associated with ipsilateral skin changes, and AK is often binocular[16]. The fluorescence staining of the cornea in case 1 was easy to be misdiagnosed as HSK. However, the HSK lesions were mainly map or dendritic epithelial defects with terminal enlargement, and the main manifestation in our case 1 was subepithelial point clump infiltration. Case 2 showed scattered point-like infiltration, which was easy to be misdiagnosed as AK, but its point-like infiltration focus was significantly larger than that of AK, and it was monocular. And AK is often a uniform, scattered stroma invasion of the whole or most of the cornea[20]. For case 3, when COVID-19 infection has been confirmed, SARS-CoV-2 RNA has been detected in the corneal scrape sample, combined with ocular clinical symptoms, the diagnosis of SCK is unequivocal.

In our case 1 and case 2, SARS-CoV-2 detection using reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) from eye swab could not be performed. Because the nasal swab had already turned negative when the patient visited our hospital, we thought it was of little significance to do an eye swab at this time. And both patients were non-sever patients, the virus copy number may not have been high enough and only present during a certain period of disease, or it may have been diluted with anesthetic eye drops during sampling, which is highly likely to resulted in a negative eye swab result[21]. The literature shows that the presence of SARS-CoV-2 is rarely detected in ocular surface, tears, and corneal tissue in infected persons with or without ocular manifestations[17,22]. In addition, the results of SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR out of eye swabs of patients with SCK reported previously were also negative[18,23]. Although we have not conducted an RT-PCR test in case 1 and case 2, it is reasonable to diagnose the two patients with SCK based on their medical histories, eye signs associated with COVID-19 infection, and our extensive clinical experience. However, we must acknowledge the limitations of our approach, as a definitive diagnosis requires laboratory confirmation. Despite the challenges in obtaining certain tests, clinicians sometimes rely on their professional judgment and clinical expertise to provide the best possible care for their patients.

Figure 3 In vivo confocal microscopy of case 2. A) In vivo confocal microscopy of case 1 shows fragments and irregular epithelial cells in the cornea of the left eye; B) The density of nerve fibers decreased significantly; C) Dendritic cells are active and corneal stromal cells decreased; D) Vacuoles are seen in the corneal endothelial cell layer; E, F, G and H) No abnormalities were found in the in vivo confocal microscopy results at the corresponding level of the lateral eye.

Figure 4 Ophthalmic examination of case 2. A, B, C, D) the anterior segment of case 3 was photographed at first visit; C, D) anterior segment photograph during the review one week later.

Jockuschetal[24]showed that ganciclovir triphosphate from ganciclovir targets RdRp and completely stops the polymerase reaction of coronavirus. The cases of COVID-19 infection with keratitis as the first clinical manifestation reported by Zuoetal[16]also support the effectiveness of ganciclovir in the treatment of SARS-CoV-2.

According to treatment guidelines for epithelial keratitis, glucocorticoids are generally not recommended for viral epithelial keratitis because glucocorticoids are thought to promote viral replication. However, some researchers have found that topical corticosteroids can promote the recovery of SARS-CoV-2 keratoconjunctivitis[18]. In our case, although the patient had corneal epithelial defects, it was mainly manifested as viral corneal stromal infiltration, so our treatment plan was determined to be Ganciclovir Ophthalmic Gel and Fluorometholone Eye Drops, supplemented with corneal repair drug Deproteinized Calf Blood Extract Eye Gel. A week later, all patients showed significant improvement.

It is worth noting that none of our keratitis patients experienced significant pain. We hypothesized that on the one hand, the corneal epithelium was not badly damaged, and on the other hand, the corneal sensitivity was reduced due to the decrease of subepithelial nerve fibers. Previous studies have also suggested that SARS-CoV-2 infection may induce small fiber neuropathy[25], corneal subbasal nerve fiber morphology change and nerve fiber density decreased accompany with DC increased significantly[26], which was consistent with our research results.

In conclusion, we found that the main manifestation of SCK was subepithelial infiltration of the cornea, which would lead to reduced nerve fibers and less obvious pain. Ophthalmologists should pay attention to differential diagnosis of COVID-19 patients and increase counseling to prevent people from delaying eye care. All patients recovered well, proving that our treatment regimen with Ganciclovir Ophthalmic Gel and Fluorometholone Eye Drops is scientifically effective. We hope that our findings will provide ophthalmologists around the world with ideas for the treatment of novel coronavirus keratitis.