灾害事件后如何认知遗产

——基于瑞典森林火灾后的风景研究

著:(瑞典)安德鲁·巴特勒 译:张文宇 于倩 校:赵烨

最近10年,北欧地区日益受到气候变化的严重影响,其中包括洪水、风暴、干旱和野火等灾害事件[1]。据预测,未来几十年内这些事件的发生频率将会进一步增加,它们将导致巨大的灾难性风景变化,对人类与周围环境的关系产生深远影响,这引发了对 “新型”风景未来发展的探讨。

瑞典位于北欧地区,以森林为主。国土面积约70%被森林所覆盖,其中生产用森林占国土面积的58%,这凸显了林业在瑞典经济中的重要性。森林作为主要的土地覆盖类型,对人和社区以及他们对风景的识别和联系产生了深远影响。虽然大部分土地归私人所 有,但“公 共 使 用 权”(瑞 典 语:Allemansrätten)的存在促进了人与森林的密切关系。公共使用权使当地人将户外休闲视为一种必需品[2], 森林在日常休闲中扮演着重要角色[3]。公共使用权本身也经常被视为国家认同和自我形象的推动力,这项权利为所有人提供了接触大自然的机会,也是非物质风景遗产的一部分。

本研究旨在从风景变化的角度阐述如何认识森林火灾后的风景遗产,揭示并塑造风景的多种要素,并探讨风景的定义及其自明性。通过介绍2014 年韦斯特曼兰地区的火灾案例,简要概述风景作为遗产的认知方式。在此基础上,论述火灾前后韦斯特曼兰地区风景遗产话语和特质的变化。最后,从过去的联系和未来的遗产两个方面讨论与火灾地区相关的遗产话语的发展。

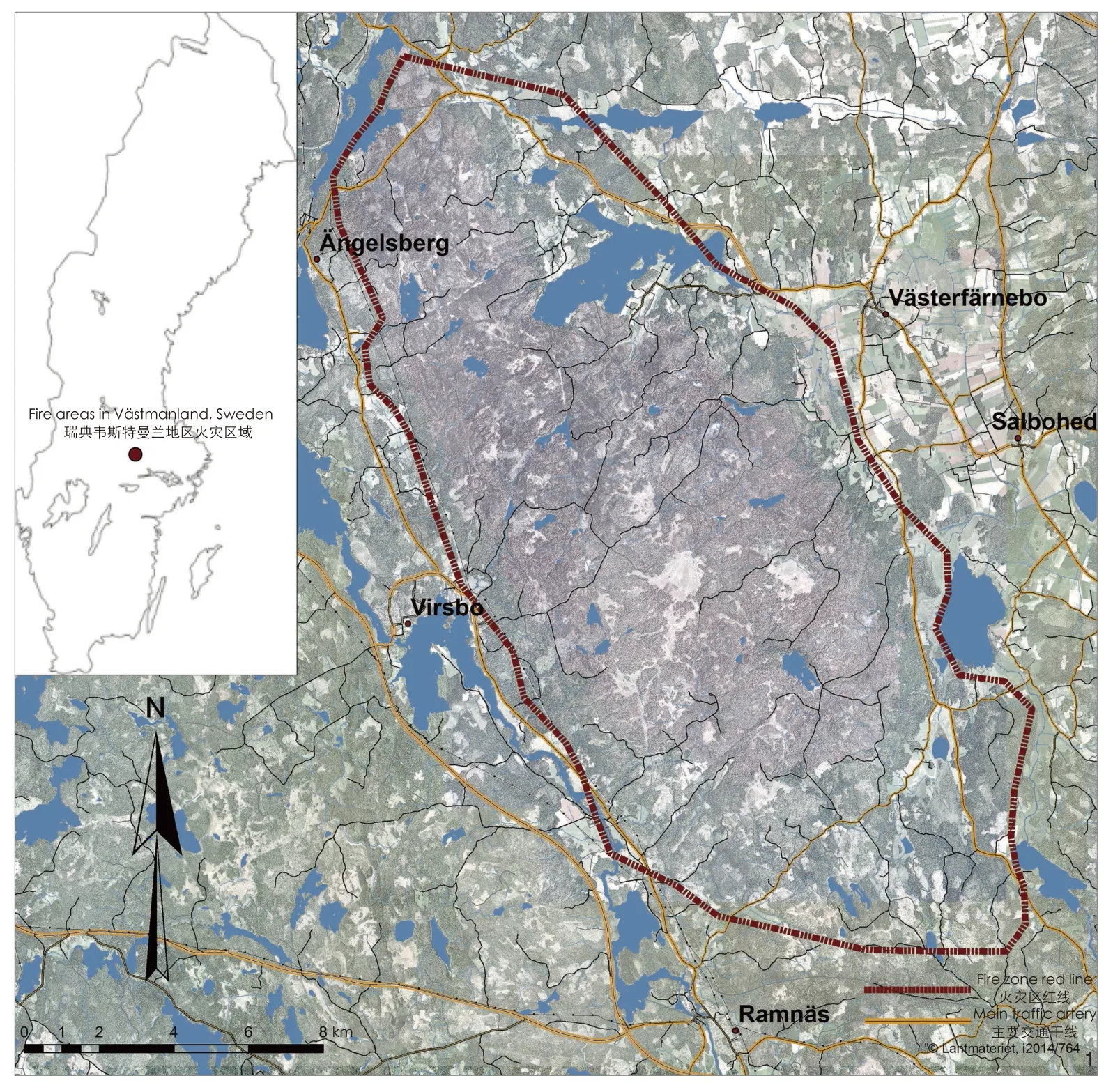

2014年8月4日,瑞典媒体齐聚瑞典中部的韦斯特曼兰(图1)。5天前,这里还是一片默默无闻的普通森林,2014年7月31日,由于长时间的炎热干燥天气,森林火灾风险达到了极端水平(5E,瑞典6级指数中的最高级别),在伐木区进行林业工作时,不慎引发火灾。11 天后,随着天气条件的改善,风力减弱、湿度增加,再加上大批消防队员的共同努力,火势才得以控制。

1 韦斯特曼兰大火的位置及范围Location and extent of Västmanland fire

这一场突如其来的大火彻底改变了这一地区的自然环境,改变了人们赖以生存的实践方式、经验和观念。大火摧毁了主要的生物群落,严重影响(并产生了新的)考古遗址,并导致各种物理变化,包括表土枯竭和河道淤塞,20多座房屋被夷为平地,近1 200人需要撤离。由于社会和自然限制条件的改变,韦斯特曼兰地区的风景发生了巨大变化,曾经界定风景功能的人类实践活动和习俗不再适用。为各种活动、情感和身份提供空间的风景消失了;觅食、狩猎、散步和劳作的区域变得面目全非。

1 风景作为特质和遗产的载体和来源

风景价值的丧失取决于如何认识风景,以下本研究将简要概述如何理解风景。《欧洲景观公约》(ELC)推动了“风景是可以感知的实体”理念,将风景定义为“人们所感知的区域,其特征是自然或人为因素作用和互动的结果”[4]。

每个体验和感知风景的人都有自己的理解体系,从而对同一风景产生多种主观认知。通过参与风景所建立的联系,在支持和形成风景自明性方面发挥着重要作用[5]。这种复杂性导致了在风景价值、身份特质和言论之间的潜在冲突[6]。

由于风景是“自然或人为因素相互作用”[4]的结果,它们代表了社会的共同遗产。风景为社会的过去提供了历史的记忆;为当代社会解读共同遗产提供了纪念性遗迹和文献参考。风景蕴含着文化传统和习俗,具有多重意义。

风景为历史权力结构提供了有形和无形的痕迹,代表了存在于风景中的实践以及当地非物质性的法律和习俗[7]。这些习俗受到地区、国家和国际议程的制约,因此地域风景形成的原因不一定是其自身演化,而是可持续发展议程、森林政策等倡议及其背后的政策。

由于风景代表了“文化与自然进程之间的动态互动”[4],其并非是静态的。风景变化影响着人类与周围环境的互动方式[8]。风景变化的特质会影响人对周围环境的感知和评价,并影响他们与风景保持联系的能力。因此,建立在风景基础上的特质和遗产也是动态的,反映了社会变革和文化习俗,产生了风景和围绕风景展开的论述。

尽管变化是不可避免的,但变化会让人对被改变的事物产生消极态度。尤其是当变化是不可预测的、剧烈的,如野火等自然灾害时[1]。灾后的风景变化及其感知反映了风景的价值。

2 瑞典风景变化的驱动因素:森林火灾前后的风景变化

2.1 韦斯特曼兰火灾发生的背景

与所有风景区域一样,韦斯特曼兰的防火区域从来都不是固定的。该地区的动态范围受到景观管理(这里指的是林业制度和实践)以及地方、地区、国家甚至国际议程和话语的影响和界定。

火灾发生区域以及其周围的大部分地区都以生产性森林为主;在20世纪,生产性森林不断发展,扩张日益严重[9]。瑞典和世界上许多国家一样,数百年来一直在开发森林,用于提供燃料、建筑木材、狩猎区,生产钾肥、焦油、木炭,进行森林放牧等。根据历史经验,森林是一个真正的多功能场所,其活动和价值与当地生产活动以及环境相关。然而,林产品工业、锯木厂、纸浆和造纸厂以及其他工业原料的增加意味着林业在瑞典19世纪的工业化进程中扮演了重要角色。韦斯特曼兰就是典型案例,该地区被认为是瑞典工业最发达的地区之一,但过度开发导致森林资源枯竭,引发了旨在解决森林覆盖面积减少的森林政策性活动,从而对瑞典工业发展造成了巨大的影响。因此,包括补植在内的国家管理理念应运而生。在同一时期,农业合理化意味着森林放牧不再可行。迫于国际压力,人们开始在生产力较高的土地上强化农业,这导致边缘农田被放弃[9]。

在全球需求的推动下,国家管理理念和农业合理化这两项国家议程都使森林覆盖率上升,而这一结果是通过植树造林和自然再生来实现的。这极大地改变了风景,形成了大面积的森林覆盖,也使风景沦为单一的主要用途:木材生产。

然而,国家行使的公共使用权意味人和社区与他们附近的风景形成了密切的关系,并通过一系列的风景设计提升了当地对风景的管理水平,尽管这与当前的森林产业相悖。通过公共使用权开展的活动不仅对人与周围环境的联系非常重要,而且对于人类福祉的发展也非常重要[10]。

2.2 韦斯特曼兰火灾前后的风景

2.2.1 韦斯特曼兰火灾前的风景特质

韦斯特曼兰地区拥有丰富的考古遗产,最早可以追溯到石器时代。发生火灾的贝格斯拉根区域位于韦斯特曼兰地区,包括至少4个县(图1),虽然边界不明确,但面积广阔。该地区工业景观的利用可以追溯到2 000多年前的金属生产。然而,目前该地区正在探索将生态和文化遗产作为乡村发展的基础,这些“公共”身份已融入居住和体验该地区的人们的意识中。然而,火灾的影响范围仅仅是韦斯特曼兰地区的一小部分。

在历史上,该地区曾是西部大型钢铁厂与东部小规模农业的分界线,这种分界在当前的所有权模式中仍然十分明显。该地区在历史上曾隶属于4个独立的教区,而如今则位于Norberg,Sala,Fagersta和Surahammar这4个不同的城市管辖之下。尽管这些城市的边界是由立法和政治手段确定的,但它们无形之中形成了一个框架。在这个框架中,既能够形成共同的身份,提供一个公认的边界,又能够各自独立,形成“我们”和“他们”的区别。

这些“公共”身份在该地区的风景中得到了体现,并取决于与特定地方、市政当局、教区的关联,以及地方、地区、国家或国际议程对该地区的定义。因此形成了多重强烈的“我们”身份。

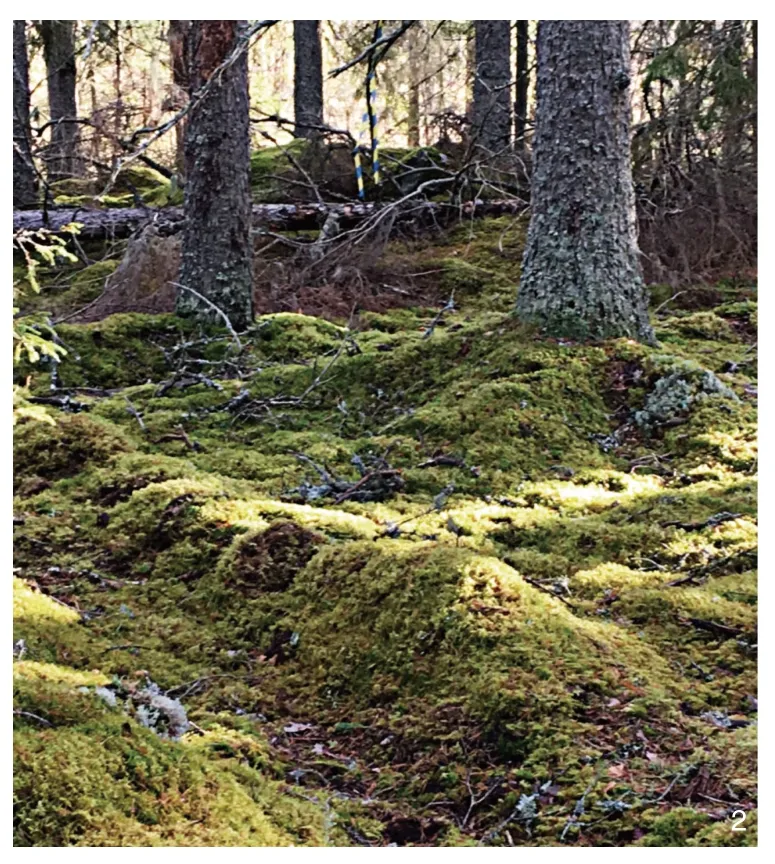

风景具有自明性,通常被称为“风景特质”(图2)。风景特质评估描述了界定一个地区独特性的共同遗产、过程和元素。在2012年对当前火灾影响区域进行了风景特质评估,该评估采用广泛、通用和客观的术语,将森林火灾区域描述为沼气地(瑞典语:Nedre Bergslagen)和森林工厂(瑞典语:Brukens Skogar)两个独立的风景特质区域。“该地区地势起伏,海拔为50~100 m。河谷、小平原、凉亭区、湿地区和荒野区等共同构成了森林地区的风景多样性,但该地区很少有关键的生物群落,根本原因在于森林所有者进行的大规模森林生产,使生物生存空间遭到破坏”。对森林工厂的描述也是类似的,只是有一些细微的差别:“(拥有)布局紧凑的森林道路网络,范围广阔的沼泽区以及种类丰富的自然保护区”。

2 火灾前该地区的特征Character of the area prior to the fire

2.2.2 新地理,新遗产:韦斯特曼兰火灾后的风景特质

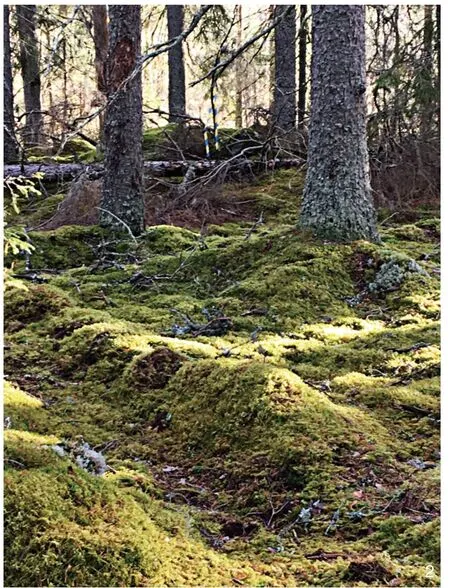

自然力量不会考虑人类在风景中构建的边界、身份和话语权。火灾的发生是快速的,然而,无论是物理影响还是感知影响,火灾都会导致风景发生长期的、灾难性的变化[8]。韦斯特曼兰大火造成的物理影响包括地下水位变化和洪水泛滥[11],土壤、植被急剧流失,植被组成变化,以及对该地区动物群的影响(图3)。然而并非所有变化都是糟糕的,生物多样性的长期增长和对该地区遗产的进一步了解都被视为积极结果。

3 火灾后一年的特征Characteristics of one year after the fire

在火灾发生前,当地居民一直在使用这片森林,然而火灾的发生切断了他们与森林风景之间的情感纽带,导致他们与该地区的联系急剧减少。个人受火灾影响的程度取决于多种因素,包括性别、年龄、从事的活动以及火灾前对风景的参与程度。火灾发生前,该地区是一系列活动的举办场所,然而火灾发生后,当地居民开始将其视为一个缺乏活动的、需要回避的地方。火灾和媒体的关注塑造了新的身份认同感,因为该地区的居民开始意识到别人是如何看待他们这些火灾地区的居民的,以及他们认为别人是如何看待他们的。

2016年,该地区的风景特质评估有了更新。该评估文件将受火灾影响的地点确定为一个独立的特征区域。对于当地居民和外来者而言,风景是被单一事件塑造的。火灾在风景中还赋予了一种新的时间性,即火灾前的记忆和经历过火灾后的体验。

大火创造了新的地理环境,包括自然环境和感知环境。森林中的边界、路径和地貌,以及它们所参与的活动都已消失。与此同时,出现了一个新的风景边界,为灾后遗产的认知创造了一个潜在的领域,为对新身份和未来遗产的认知提供了载体。

2.3 局外人的议程:其他人对该事件的评议

现在,我们将进一步探讨该事件的发展。火灾地区的风景特质和未来遗产是怎样的?谁将决定政策议程,哪些未来价值将得到认可?灾难性事件改变了该地区的边界,使它变得模糊不清。在火灾后,该地区的风景经历了彻底的变革,成为文化、政治实体展示和宣扬其无形影响力的场所。举例来说,21位学者在瑞典发行量最大的报纸上提议将火灾地区开发为自然保护区:“(这是)独一无二的机会,韦斯特曼兰的火灾给人类带来了灾难性后果,但同时也为我们提供以低成本创建斯堪的纳维亚半岛南部最大的森林保护区的机会。我们敦促环境部长尽快采取行动,以免错过这个历史性的时刻。”[12]

相关部门在地表温度较高、火灾后的控制和限制措施仍在实施的情况下,提出了一个森林保护提案:野化议程。这一提议的核心是经济成本,而忽略了当地居民已形成认知的本土风景价值观。为了响应建立自然保护区的号召,土地所有者组织和当地居民的代表再次对该提案进行了争论,重点关注在本土工作的利益相关者。然而,当前的辩论主要围绕建立自然保护区展开,仅限于野化议程的讨论。由于媒体等方面的争论,该议程颇具争议,这不仅与当前的行动有关,还与风景所代表的意识形态有关,包括人们的依恋、愿望和倡议。

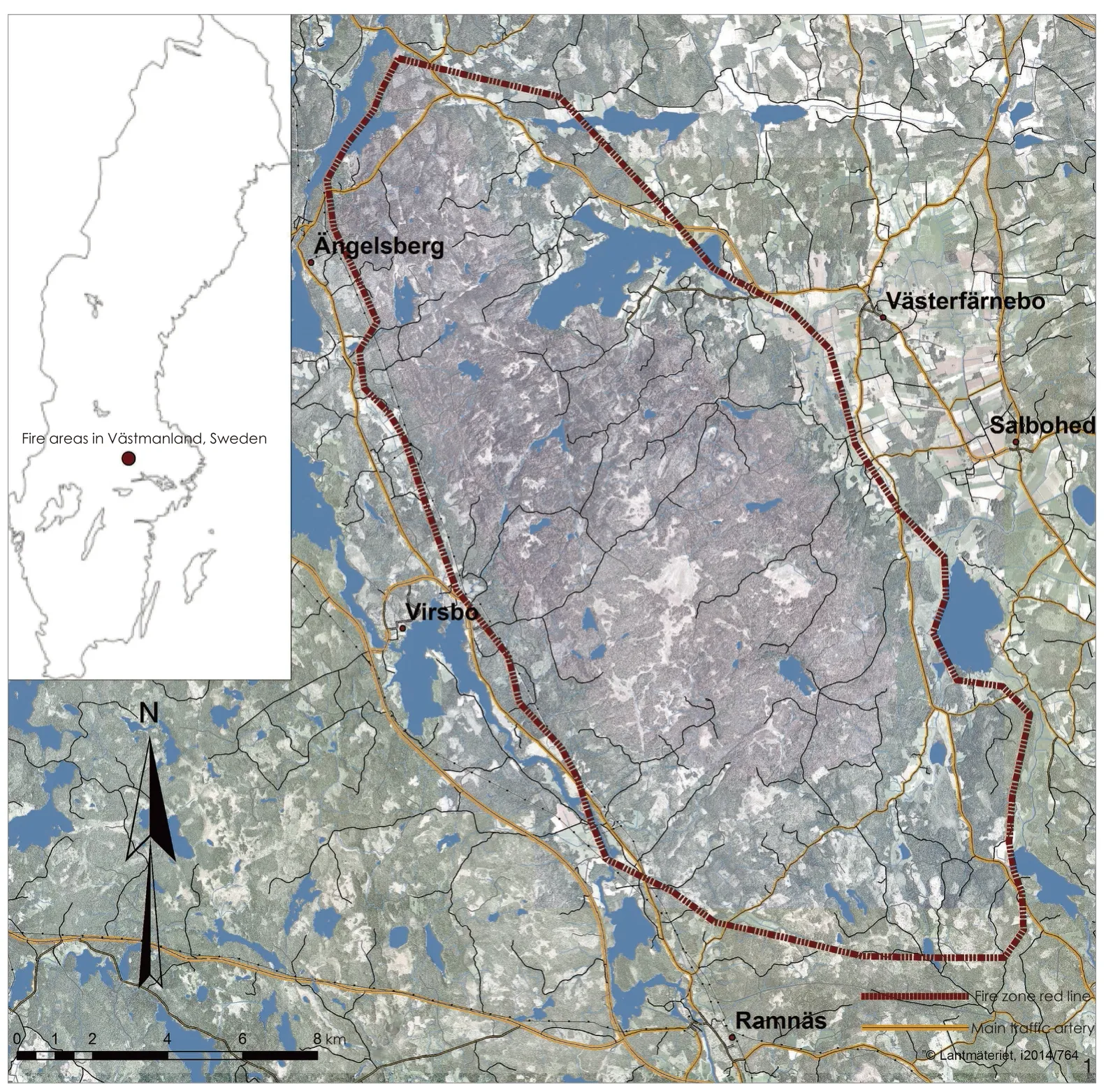

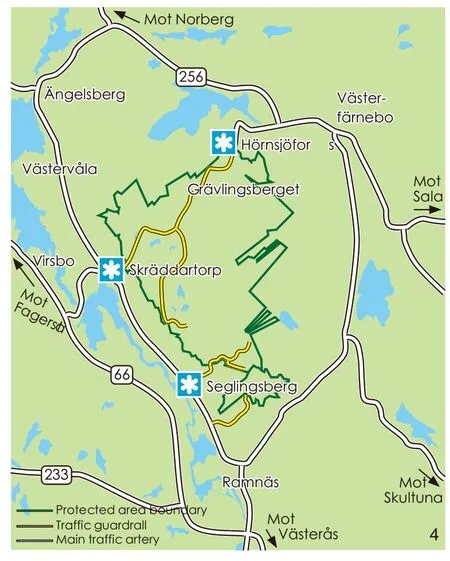

大火被扑灭一年多后,政府决定将火灾现场的大部分区域划为自然保护区。在该地区的西部,大型林业公司通过用他们的土地换取该地区其他地方的森林资源,为保护区创造了一个明显的边界;然而,在该地区的西部,小规模森林所有者对森林的商业价值需求较少,对土地的依恋程度也在不断提高。从锯齿状的边缘可以看出,所有者们选择保留对土地的所有权(图4)。目前,火灾区域主要由县行政委员会指定的Hälleskogsbrännan自然保护区(6 420 hm2)和国有林业公司Sveaskog拥有的生态公园Öjesjöbrännan(1 570 hm2)组成。尽管公共使用权在理论上仍然占主导地位,但保护区和生态公园的非经营性质限制了人们进入该地区,且枯死的树木有着再次引发火灾的安全隐患,未来大量密集的再生先锋树种将更加限制人们的进入。

4 Hälleskogsbrännan自然保护区地图,显示自然保护区东部有争议的边界Map of Halleskogsbrännan, showing the disputed boundary to the east of the nature reserve

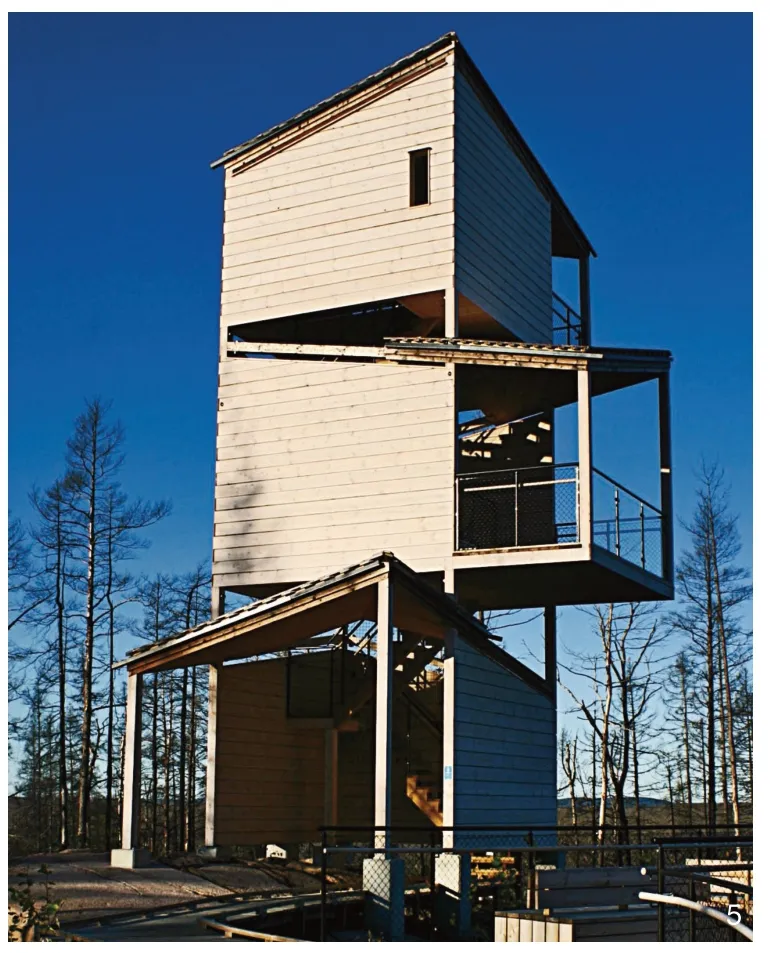

外来者主导了受灾地区风景变化的评议,强调了风景的动态性和与之相关的价值观。然而,这种论述却忽略了当地居民的多元化价值观和愿望。游客中心的设计反映了外界对此次事件的态度,该建筑就是当地风景的标识物,它为观察火灾区的活动和风景提供了视野,协调了火灾区的活动和风景(图5)。这种风景只能通过自身体验来感知,是一种无法触摸的、抽离的体验,与公共使用权的理念截然不同。

3 结语

在韦斯特曼兰地区,火灾被描绘成一种具有破坏性力量的事件,它揭示了该地区风景演变的历史进程,加深了人们对该地区历史的认识,同时也创造了一张空白的画布,让当地居民可以对场地赋予新的价值和愿望。在韦斯特曼兰大火之后,外来学者们的声音主导了讨论的进程,正是这些外来者决定了该地区的发展方向,最终塑造了该地区的遗产导向。该地区从当地社区的风景资源转变为研究人员、利益群体和好奇的外来者的讨论资源,而国家议程和利益战胜了当地的风景价值观。

自然保护区的设立延续了森林火灾的历史,这与被破坏和充满回忆的事件相关。然而,火灾区域也象征着焕发活力和创造新事物的地方。设立自然保护区是基于火灾和复兴的观念,但却忽视了这片景观中已经存在并将继续存在的各种微妙而多样的实践活动[1]。那些曾经受到公众使用权和非物质遗产属性支持的实践,如今被野化实践和对以火灾遗产作为新起点的期望所取代。

图片来源:

图1 从 Lantmäteriet 网站下载,经瑞典农业科学大学许可;图4从 JG Media 21网站下载,由Jonas Lundin绘制;图2、3、5由作者拍摄。

(编辑 / 项曦)

著者简介:

(瑞典)安德鲁·巴特勒 / 男 / 博士 / 瑞典农业科学大学农村与城市发展系副教授 / 研究方向为景观规划的身份认同和公众参与问题

作者邮箱: andrew.butler@slu.se

译者简介:

张文宇 / 男 / 青岛理工大学建筑与城乡规划学院在读硕士研究生 / 研究方向为滨海山地生态园林与景观设计

于倩 / 女 / 青岛理工大学建筑与城乡规划学院在读硕士研究生 / 研究方向为滨海山地生态园林与景观设计

校者简介:

赵烨 / 女 / 博士 / 青岛理工大学建筑与城乡规划学院副教授 /研究方向为风景园林遗产保护、风景园林规划设计、国家公园与自然保护地

BUTLER A.Which Heritage Is Recognized After Catastrophic Events: A Study of the Aftermath of Forest Fire in Sweden[J].Landscape Architecture, 2023, 30(12):105-113.DOI: 10.12409/j.fjyl.202310260482.

Which Heritage Is Recognized After Catastrophic Events: A Study of the Aftermath of Forest Fire in Sweden

Author: (SWE) Andrew Butler Translators: ZHANG Wenyu, YU Qian Proofreader: ZHAO Ye

Abstract:[Objective] This paper describes how to recognize the legacy of landscapes after forest fires from the perspective of landscape change,revealing the multiple factors that shape landscapes, discourses about landscapes, and associated identities.[Methods] A case study approach was used to analyse the driving factors in the landscape of Västmanland, Sweden;and the development of heritage discourse in relation to the fire area was discussed in terms of both past connections and future heritage.

[Results]Landscapes, as carriers and sources of identity and heritage, are characterized as a result of the action and interaction of natural or human factors.The drivers of change in the Swedish landscape are influenced and defined by landscape management.[Conclusion] The legacy of the forest fires continues with the establishment of nature reserves, but for a place like the fire zone, which represents a place of rejuvenation and creation of something new, it is important to first understand the values and aspirations of the local population, and then define the goals of the post-disaster landscape legacy in conjunction with the “external actors”.

Keywords:landscape change; forest fires; landscape heritage; Västamanland of Sweden

©BeijingLandscape ArchitectureJournal Periodical Office Co., Ltd.Published byLandscape ArchitectureJournal.This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license.

Acknowledgments: Thanks to ZHAO Ye, the associate professor in the College of Architecture and Urban Planning, Qingdao University of Technology, for her assistance of the commissioning the manuscript for this paper.

Over the past decade, Northern Europe has increasingly been exposed to the effects of climatic change through: flooding, storms, drought and wild fires[1].Such events, which are predicted to increase over the coming decades, create dramatic and catastrophic landscape change impacting on how individuals relate to their surroundings and at the same time instigating discussions on the futures of these “new” landscapes.

Sweden, located in Northern Europe, is predominantly forested.Approximately 70% of the land is tree-clad with production forest covering 58% of the nation’s land area.Consequently,forestry represents a significant economic concern.The dominance of forest as landcover, has also informed the identity and connections that individuals and communities develop to their landscape.Despite the majority of land being in private hands, theses connections to the forest are allowed to flourish due to “Allemansrätten”.Allemansrätten (Swedish), frequently translated as“the right of public access”, provides access to nature for all.Allemannsrätten has resulted local outdoor recreation being viewed as a necessity[2],with forest having an Important role in everyday recreation[3].Allemansrätten is also frequently seen as a driver of national identity and self-image, in its own right.It forms part of the intangible landscape heritage.

This paper lifts the plurality of factors at play which have formed the landscape, discourses on the landscape and associated identities.In the next section it introduces the case which will be addressed in the paper, the 2014 fire in Västmanland.This is followed by a brief overview of how landscape is used in the paper and its relevance for the case.A brief overview of the discourses and identities at play in the landscape of Västamanland before the fire is then presented,both before and after the impact of the fire.Finally it discusses the developing discourse relating the fire area, in relation to the past connections and future heritage.

On the 4th of August, 2014, the Swedish media gathered in Västmanland in central Sweden(Fig.1), in area which had 5 days previously been a relatively unknown forest.On the 31st of July 2014, after a prolonged period of hot, dry weather when the forest fire risk reached an extreme level(5E, the highest, on the Swedish six scale index), a fire was inadvertently started during forestry work on an area of clearcut forest.Eleven days later following improvements in the weather conditions brought about a reduction in wind and increased humidity combined with a concerted effort from an extensive team of fire fighters helped to contain the fire.

A single dramatic event catastrophically changed the physicality of this area, altering the elements on which practices, experiences, and perceptions have been built.The fire destroyed key biotopes, severely impacted (and revealed many new) archaeological sites and brought about a variety of physiological changes including depletion of topsoil and silting of watercourses, razed over 20 houses and required almost 1,200 people to be evacuated.The landscape drastically changed and the individual practices and customs which once defined the use of the landscape no longer fit, as social and physical constraints altered.The landscape which provided a space for activities,attachments and on which identities were formed,disappeared; areas for foraging, orienteering,hunting, walking and working were now unrecognizable.

1 Landscape as a Bearer and Source of Identity and Heritage

Loss of landscape values is reliant on how we recognize landscape; in the following section this study briefly outlines how landscape is understood.In a European context, theEuropean Landscape Convention(ELC) has pushed the rhetoric of recognizing landscape as a perceived entity in policy.TheELCdefines landscape as: “an area, as perceived by people, whose character is the result of the action and interaction of natural and/or human factors”[4].

1 Location and extent of Västmanland fire

Each individual who experiences and perceive the landscape creates their own meaning of the landscape, leading to a multitude of subjective understandings of the same landscape.The connections developed through engagement in the landscape plays a significance role in supporting and forming identity[5].This complexity results in potential conflict over what values,identities and discourses are recognized in the landscape[6].

As landscapes are areas whose character is the result of “action and interaction of natural and/or human factors”[4], they represent a society’s common heritage.The landscape provides a living history of a societies past; a monument and documentation of a shared heritage, which is read by contemporary society.A landscape is loaded with cultural traditions and customs fashioning a multiplicity of meanings.

The landscape provides both tangible and intangible traces of historic power structures,representing the practices which exist in the landscape and the immaterial laws and customs which lie over the land[7].These customs are framed by regional, national, and international agendas hence the place where a landscape is created is not necessarily the point where it exists.Initiatives such as the sustainability agenda, forest policies and the politics behind them all shape the landscape.

As landscape represents the “dynamic interaction between cultural and natural processes”[4]landscape cannot be static.The transformation of the landscape influences how individuals and communities interactions with their surroundings[8].The character of the landscape change influences how individuals perceive and value their surroundings, and influencing their ability to maintain connections with their landscape.Consequently, the identities and the heritage which are founded on landscape are also dynamic,reflecting societal changes and cultural practices which shape the landscape and the discourses which revolve around it.

Although inevitable, change can cause a sense of loss for that which has been altered.This is especially true when alterations are unpredictable and dramatic, as exemplified by natural disasters,such as wildfires[1].Change or perceptions of change to the landscape also bring to the fore values attached to the landscape, as made evident post disaster.

2 Drivers of Landscape Change in Sweden: Landscape Change Before and After Forest Fires

2.1 Background to the Västmanland Fire

As with all landscapes, the fire area in Västmanland has never been static.The dynamism of this area has been influenced and defined through the management of the landscape in this case the forestry regimes and practice, and the local, regional, national and even international agendas and discourses that define the regime.

2 Character of the area prior to the fire

The area containing the fire area along with much of the wider region is dominated by production forest; a picture which has increasingly developed over the past century[9].In Sweden, as through much of the world, forests have been exploited for centuries for fuel, construction timber, hunting grounds, production of example potash, tar, charcoal and use for forest grazing.Historically, the forest was truly a multifunctional place with activities and values relating local production to the local context.However, an Increase in forest product industries; saw mills,pulp and paper plants as well as raw material for other industries meant that forestry played a large role in the industrialization of Sweden during the 19th century.This was especially true in Västmanland, historically considered one of Sweden’s most industry rich areas.Excessive exploitation led to depletion of the forest resources.This brought about a forest politics aimed at addressing the diminishing tree cover and the repercussions this had for the bourgeoning industries of Sweden.Consequently, national ideas of management including replanting were developed.During the same period, rationalization of agriculture meant that forest grazing was no longer a viable proposition.The move to intensify agriculture on the more productive lands in response to international pressures led to the abandonment of marginal agricultural lands[9].

Both of these national agendas, driven by global demand, led to increased forest coverage,brought about through planting and naturally regenerate.This drastically changed the landscape,resulting in extensive forest coverage, reducing the landscape to a single dominate use: timber production.

Yet at the same time Allemansrätten, the national right to roam, means that individuals and communities develop strong bonds to their near landscapes.Through a series of acts of landscaping(practices undertaken in the landscape) meaning,connections and even a sense of ownership develops.A level of local stewardship of the landscape is formed, which is at times at odds with the rational forest industry.The activities developed through Allemansrätten are important not just for connection to the landscape but also for individuals wellbeing[10].

2.2 View of Västmanland Before and After the Fire

2.2.1 The Pre-Fire Landscape of Västmanland

Västamanland has an archeological heritage,etched across the county stretching back to the earlier settlers of the Stone Age.The fire area also lies in Bergslagen (Fig.1), a broad and ill-defined area encompassing at least 4 counties with a history of industrial landscape use that began with production of metals more than 2,000 years ago.However, the region is currently in the process of exploring new forms of development, building on the ecological and cultural heritage as a base for rural development.These “public” identities become subsumed in the consciousness of those inhabiting and experiencing this region.However,the fire affect area was only a small part of these larger region identities.

Historically this landscape represented a border between the large iron works of Ängelsbreksbruk and Virsbo in the West and the small scaled farms in the east, a division still evident in the ownership pattern today.The landscape was historically part of four separate parish and today the area falls within the borders of four different municipalities: Norberg, Sala,Fagersta and Surahammar.Although these municipal boundaries are formed by legislation and political decision, as opposed to customary actions,the municipalities form a frame in which joint identity can form providing an accepted boundary in which an “us” and “them” can materialize.

These “public” identities have all been played out on this landscape, reliant on where it is related to, which municipality, which parish or how the local, regional national and even international agendas has defined the area.Creates a multiplicity of strong “we” identities.

It has also been claimed that the landscape has an identity in its own right, often refers to a landscape character (Fig.2).Landscapes character assessments describe the common heritage,processes and elements which define an areas uniqueness.A character assessment of what is now the fire affected area was undertaken in 2012.The assessments recognize the forest fire area as small parts of two separate character areas Nedre Bergslagen (Swedish) and Brukens Skogar(Swedish), which are described in very broad,generic and objective terms: “Rolling topography,ranging from between 50-100 meters above sea level.Contains river valleys and small plains that stand out in the forested landscape….Areas of summerhouses, wetland areas, heathland create diversity in the forest area with few key biotopes.Predominantly large-scale forest production,distributed among a few large forest owners”.The description for Brukens skogar is in a similar vein with slight nuances “Relatively tight network of forest roads.Rich in marshes, big marshes, rich with nature reserves”.

2.2.2 A New Geography, a New Heritage:Landscape Qualities After the Västmanland Fire

Natural forces take no account of these constructed boundaries, identities and discourses that humans lay over the landscape.Fire represents a quick acting phenomenon.However, the impact on the landscape, both the physical and perceived can result in long-lived, calamitous change[8].The physical impacts of the fire in Västamanland included change to the water table and flooding[11];dramatic loss of soil cover; changes to the vegetation composition; and impact to the fauna of the area (Fig.3).Not all changes were for the worst.Long-term increase in biodiversity and increased knowledge of the heritage of the area are seen as positive consequences.

3 Characteristics of one year after the fire

The local residents who utilized this landscape prior to the fire, experienced a dramatic loss of connection to the area after the fire as their emotional bonds to the landscape were severed.The degree to which individuals were impacted by the fire relied on numerous factors including gender, age, activities undertaken and level of engagement in the landscape prior to the fire.Before the fire, the area represented a series of places where activities were undertaken, yet in the of the aftermath the area was recognized by local residents as an area void of activities, a landscape to avoid.New identities have been built by the fire and the media focus, as inhabitants of the area became recognized how others see them, as residents of the fire area, and how they perceive others see them.

In 2016, the landscape character assessment was updated.The document which was produced identified the fire impacted site as a character area in its own right.For both locals and outsiders, a landscape was created by a single event.The fire has also developed a new temporality in the landscape, there now exists a remembered before as well as an experienced after.

The fire created a new geography, both physical and perceived.Boundaries, routes and features within the forest, and the activities they facilitated disappeared from the forest.Familiar places were no more.At the same time a new boundary was created in the landscape, creating a potential area for discussion, a vessel for aspirations of new identities and future heritage.

2.3 An Outsiders Agenda

Where does the story go now? What is the next chapter for the identity and the future heritage of this area? Who defines the agenda and which future values are recognised? After catastrophic events restrictions in the area are transformed and blurred.After the dramatic changes of the fire the landscape became the sites where cultural and political entities manifested and asserted their unseen influence.This is exemplified by a proposal from 21 academics, in the largest circulated newspaper in Sweden, to develop the fire area into a nature reserve and the subsequent opposition to the proposal the discourse became around a rewilding agenda either for or against: “Unique opportunity.The fire in Västmanland had disastrous human consequences yet at the same time provides the opportunity to create by far the largest protected forest area in southern Scandinavia at low cost.We urge the Minister of the Environment to act quickly, before the historical moment is missed.”[12]

This proposition for a protected forest came forth while the ground was still warm and post fire controls and restrictions were still in place, focused on a completely new agenda for the area; a rewilding agenda.What was central to this proposal was the financial cost of achieving this with little consideration for the values for those who had recognized this as their local landscape.In response to the call for a nature reserve, representatives for different landowner organizations and local residents argues again the proposal, focusing on those who work and engage in the landscape.However the debate was now build around the creation of a nature reserve, limiting the discussion to a rewilding agenda.Thanks to such debates in the media etc.the area became a struggle over a symbolic space, not relating only to the action at hand but also the ideology the landscape represents including people attachment, aspirations and agendas.

4 Map of Halleskogsbrännan, showing the disputed boundary to the east of the nature reserve

5 Viewing tower at Halleskogsbrännen, a site for viewing

landscape rejuvination

A little over a year after the fire was extinguished, the decision was made to designate a large portion of the fire areas as a nature reserve.In the west of the area large forest companies traded their land for forest resources elsewhere in the county, creating a clear edge to the reserve.However, in the west of the area, small-scale forest owners had less commercial demand from the forest and developing attachment to the land.This can be seen in the serrated edge revealing owners who chose to retain their ownership of their land(Fig.4).Today the fire area is dominated by the nature reserve, Hälleskogsbrännan (6,420 hm2)designated by the county administrative board and an ecopark Öjesjöbrännan (1,570 hm2) owned by the state-owned forest company, Sveaskog.While Allemansrätten still in theory prevails in the area,the non-management of reserve and the eco-park inhibit access.It is recognized that the standing dead trees pose a safety risk, and then in the ensuing years extensive and dense regeneration of pioneer species will restrict access to once familiar sites.

Outsiders have defined the discourses of this local landscape impacted by catastrophic change.Dynamism of the landscape is at the fore of the values promoted, however they miss the pluralistic values, views and aspiration of residents which still lie across this landscape.The discourse on this landscape from the outside is manifested in the design of a visitor’s centre, a beacon of what this landscape is and who it is for.Boardwalks and viewing platforms (Fig.5) orchestrate movement and vistas of the fire area.The landscape is to be observed but not touched, a removed experience,counter to the ideals of allemanrätten.

3 Conclusion

In the context of Västmanland, fire has been portrayed as a destructive force; a process that revealed the past, deepening the understanding of history of the area; and an event which created a blank canvas on to which to project new values and aspirations.After the fire in Västamanland it was the voices of academics, removed from this landscape, who dominated the developing discourse.It is these outsiders who have appropriated this space and defines the direction for this area and ultimately its heritage.The area turned from a landscape resource for the local community to a resource for researchers,communities of interest, and curious outsiders.National agenda and interests have trumped over local values.

Placement of the nature reserve perpetuates the forest fire legacy.A landscape discourse linked to destruction and an event loaded with memories.Yet the fire area also represents a site of rejuvenation and creation of new.The nature reserve builds on the discourse of the fire and rejuvenation, but ignores the nuanced and diverse practices which have existed and continue to exist in this landscape[1].The practices once supported by the intangible heritage of Allemansrätten have been trumped by practices of rewilding and an aspiration for a heritage based on the fire as a new beginning.

Sources of Figures:

Fig.1 was downloaded from Lantmäteriet, which permission was obtained through Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences license; Fig.4 was downloaded from JG Media 21, and Illustrated by Jonas Lundin; Fig.2, 3, 5 were photographed by the author.