风景园林中的人地关系

——国际风景园林师联合会主席布鲁诺·马奎斯博士专访

采访:张柔然 翻译:陈欣 胡嘉鸿 校对:王长宏

布鲁诺·马奎斯(Bruno Marques)博士于2022年9月至今担任国际风景园林师联合会(International Federation of Landscape Architects,IFLA)主席,惠灵顿维多利亚大学(Victoria University of Wellington)建筑与设计创新学院副院长。他重点关注社区的健康福祉、毛利部落、康复景观以及社区参与式风景园林设计的方法与实践。此外,他也是“治疗+康复设计环境/Taiao+Tumahu”研究实验室 (Therapeutic+Rehabilitative Designed Environments, TRDE)的创始人之一,这个多学科和多机构的研究实验室致力于发展循证研究,以展示建筑、景观和技术如何支持医疗健康的相关实践。2023年4月,马奎斯主席受邀参加了第十三届中国风景园林学会年会以及由中国风景园林学会青年工作委员会主办的“国际风景园林前沿论坛暨4.18国际古迹遗址日风景园林遗产保护青年专业人员论坛”。《风景园林》杂志社有幸对马奎斯主席进行了专访,深入探讨风景园林中的人地关系。

LAJ:《风景园林》杂志社

Marques:布鲁诺·马奎斯博士

LAJ:在全球化的背景下,景观中的人地关系遭到了破坏,请问您如何看待这一现象?

Marques:出于粮食生产和经济收益等诸多不同原因,人类对赖以生存的土地进行了大量的改造,由此导致了大量破坏。我们正在努力修复这些错误,试图重新寻求与自然更好的平衡,让自然围绕在我们的身边。我们不再单纯从经济利益的角度看待自然,而是追求人与自然和谐共生。现如今在许多国家,景观的重要性相较于过去变得更为凸显,因为我们正在纠正过去的错误,而气候变化等问题一直在提醒我们仍有许多错误在等待纠正。因此我们需要风景园林师站在讨论和解决这些问题的最前沿。

LAJ:您对于毛利文化的研究颇深,毛利人的传统价值观根植于他们生活的自然景观之中,并形成一套复杂的土著知识体系。您如何看待毛利人与景观、文化与自然产生的互动?

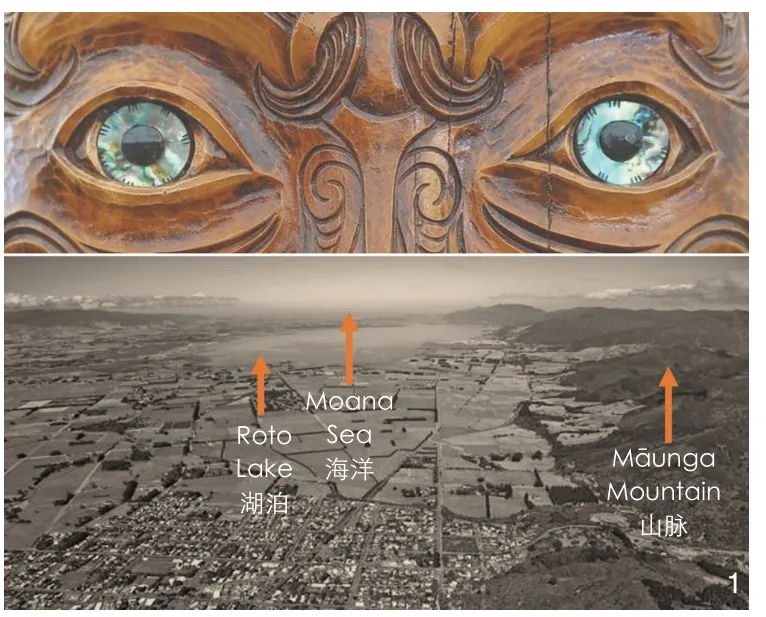

Marques:毛利文化是一种集体文化。于毛利人而言,家庭单位和整个部落的福祉尤为重要。景观定义了“他们是谁”,成为他们的身份象征。当参加毛利部落会议时,他们从不会以自己的名字作为开场白,而是先陈述他们所属的山、河、湖、海,以及他们的部落和家庭,最后才提及名字(图1)。这样的身份介绍过程自动建立了令人印象深刻的景观基础,明确了他们来自哪里,并解释了他们与特定土地之间的紧密联系。正是这样的景观与环境阐释了他们是谁,也定义了他们的存在。

1 研讨会上毛利人提及的自然景观The natural landscape mentioned by Māori at the seminar

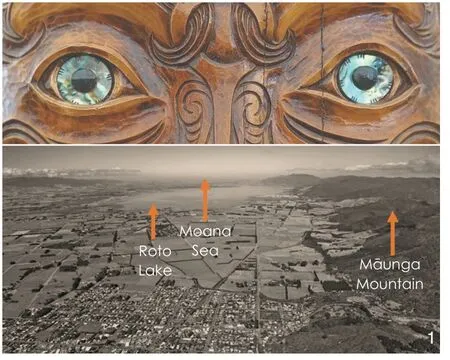

通过这种联系,我们能够了解到更多关于如何管理和尊重土地的知识,而这些与西方的理解存在很大差异。毛利人通过代际传承,将关于土地的信息以及正确管理土地的理念融入他们的身份认同中,而这些主要通过口口相传而非文字记录。这些知识与土地的管理保护有着非常紧密的联系,没有土地,就没有毛利文化,他们的行为都是受文化驱动的。对于他们来说,文化、景观与人是一体的(图2)。即便是在同一个国家,如果把人们从祖祖辈辈生活的北方土地上迁置到南方,人们会挣扎,因为那不是他们的土地,他们无法在那里找到与北方土地相联系的身份。

2 毛利人“从山到海”(ki uta ki tai)的整体景观方法Māori involve the “whole of landscape” approach known as “from mountains to sea”

随着全球化时代的到来,我们似乎需要加强个人与国际的联系。但我认为是时候意识到地方主义的重要性,并回归地方和地方特有的事物上。因为我们总是受到周围环境信息的影响,我们几乎都喜欢回到最初,回到特定环境下人与环境的原始关系。

LAJ:如今气候变化形势严峻,国际关系瞬息万变,全球化速度加快,我们的生活方式与往日大不相同,这有时会导致本土文化和经验的衰落。在此背景下,我们应该如何传承和复兴本土知识?

Marques:本土知识是不断发展变化的宝贵资源。许多本土传统和知识由于缺乏书面记录,面临丢失的风险。因此,采取适当的保护措施对于保存本土文化至关重要。

我们可以找到许多应用本土知识应对气候变化和解决入侵物种问题的成功案例。例如,澳大利亚土著居民通过控制火势来应对入侵物种的蔓延;新西兰的毛利部落拥有关于雨洪管理的传统做法。这些例子显示了本土知识在应对环境挑战方面的重要性。

作为风景园林师,我们有责任和义务运用专业知识来保护和传承本土文化,同时应对气候变化和物种入侵等问题。我们的目标是打造独具地方特色的风景园林,并为创造一个更美好的未来而不懈努力。通过与本地社区合作,我们可以更好地了解和尊重他们的传统和知识,将其融入设计中,为保护本土文化做出贡献。

LAJ:您觉得如何在风景园林设计中融入本土知识?您能否列举一些具体案例?

Marques:风景园林设计需要让人们感受到本地的特点,从而唤起本地的身份认同感。从宾馆的窗户往外看,这些建筑缺乏本地特点,我无法确定这里是在中国、美国、新加坡还是在瑞典。因此,在风景园林设计中应考虑如何将本土知识应用到具体的环境中,解决本地的问题或体现出本土特点。例如,深圳的本土知识和解决问题的方法在中国北方未必适用,因为两者的环境背景及景观存在诸多差异。由此,作为风景园林师应与当地建立更紧密的联系,探索更多有趣的、融入本地知识的设计方案。

LAJ:您如何看待拥有良好人地关系的景观能够使人获得归属感和身份认同感?在风景园林规划设计中如何塑造地方感?

Marques:针对所处环境运用设计语言、材料和植物设计出的解决方案,可以赋予人们一种地方认同感和社区归属感,因为使用者会感到熟悉并认同周围的环境,与之产生共鸣。相较于处于完全陌生的环境,设计中使用的材料、图案、传统或习俗如果并非真正来自本地,人们会感到自身并未真正融入此地,失去认同感或归属感。因此,在设计中融入地方特色,采用本地的材料、图案和传统,可以加强使用者与环境的联系,促进社区归属感的形成。这样的设计语言和元素能使人们对所处环境产生情感共鸣,并更加愿意认同并融入社区。

LAJ:您的研究领域涉及康复景观,您关注弱势群体的心理、身体及社会健康,而在您关于城市健康街道的研究中有关注到街道的包容性,这些也与今年IFLA的副主题“不让任何人掉队”(Leave No One Behind)十分契合,您如何看待这一主题?

Marques:不同个体对自然和人造环境的看法不同,这源于人们联系事物的方式不同。例如,西方人倾向于穿着运动短裤和跑鞋到滨水区跑步健身,然而这种模式并不适用于其他文化的人群,他们可能不会觉得去滨水区和陌生人一起跑步是一件乐事。比如我的祖父母经常和孙辈们在家里散步,对他们来说这种锻炼健身方式远比去滨水区跑步更为有效。

研究健康街道的主要目的是让人们意识到街道环境的价值,并让他们愿意主动走进街道。对于行动不便的人来说,街道需要更好的设计以方便使用,其中坡道和台阶的设计尤为关键,特别是对于失去行动能力的老年人而言,这样的设计可以避免摔倒引发骨折等问题。因此,我们需要特别注意生活细节,尤其是街道设计,确保公共空间的无障碍性。

从文化的角度来看,我们应该思考如何通过设计创造空间,使人们能够感受到自己的文化,并在其中感到舒适。在打造社区地方感的过程中,应当将与当地文化相关的符号、零件、材料和元素等融入城市空间的设计中。通过运用这些文化要素,让居民们获得归属感,并凝聚在一起,从而反映出他们的文化和身份认同。

LAJ:为了塑造更好的人地关系,您提及风景园林设计应该转变一个观念,即从“设计师项目”到 “社区项目”。您认为基于社区参与的风景园林设计价值和必要性是什么?

Marques:许多建筑和风景园林项目通常由缺乏与社区真正有互动的设计师主导。换句话说,设计师花费大量时间设计,这些项目可能由明星建筑师或风景园林师签署,并成为一个品牌,但并不符合社区的真实需求。真正成功的项目是那些展示不同设计方法,将公众参与的讨论融入设计过程中的项目,而不是设计师与社区脱节,提出并不能满足社区期望的解决方案。

在与社区交流时,人们可能会指出最常使用的区域,例如需要遮阴的区域,设计师应明确保留这些区域,而不是在那里放置永远不会被使用的设施。或者人们会提到在使用过程中形成的行动轨迹,设计师应保留这些路线,而不是强迫使用者绕道,否则他们还是会寻找其他捷径。在与当地社区交流时,人们会提供一些设计师可能不了解的信息,因为他们有使用这些空间的经验,了解哪些区域应该保留或放弃。

无论是在场地分析还是概念设计阶段,都需要公众参与。在反复交流的过程中,公众会给设计师提供极具意义的反馈。身处项目中,公众也会理解设计师的做法,并了解如何使用场地。相较于直接向社区提供一个设计方案,也就是我所说的“设计师项目”,让公众参与的“社区项目”需要付出更多成本,但最终的成果会更合理。

LAJ:在您的参与式风景园林设计项目中,学生在参与这个过程中给您留下了什么印象?为了让学生更加重视景观中的人地关系,我们应该更加关注风景园林教育的哪些方面?

Marques:学生初步尝试这种工作模式时,常常会感到不适,这主要源于他们对与陌生人交流的恐惧或不适应。因此,当我一开始鼓励他们改变常规,以新的方式开展项目,与不同群体和年龄段的人进行交流时,他们常常会抗拒。然而,一旦他们真正投入其中,便能看到这种方式带来的积极变化。

以我在2023年3月初发起的一个学生参与的设计项目为例,我和学生们在毛利部落中待了整整一周。起初,他们并不愿意与当地人接触,但当他们开始探索这个地方,与当地人交谈后,他们发现了许多无法通过其他途径获得的宝贵信息。这种发现使他们在推进项目时更有灵感和责任感,因为他们意识到,是当地人付出了时间和知识,他们有义务将项目推进并找出最佳解决方案。

虽然这种方法可能比传统项目耗时更多,但我认为这对学生的成长至关重要。在实际项目中,我们并不是孤立工作的,需要与其他风景园林师或专业人士协作,需要与客户和社区进行互动。我相信,随着学生对这种工作模式的深入接触和实践,他们的经验会日益丰富,他们的设计能力也会得到提升。这无疑是一个积极的体验和结果。

LAJ:遗产的保护管理与发展常常涉及复杂的地方社区与原住民问题,请问您如何看待地方社区或原住民和遗产保护与发展的关系?

Marques:找到平衡是至关重要的。根据我与原住民合作的经验,他们对自身的文化和传统有着强烈的自豪感,希望其他人能够学习并尊重它们。这些文化和传统极其引人入胜,当人们了解它们时,会产生欣赏和尊重之情。然而,欣赏与为旅游业开发之间的界限微妙,过度开发可能会对这些资源和景观造成更大的破坏。

如果让原住民参与这些讨论,进行周全的规划,我们就可能在文化交流和自然资源保护之间找到一个平衡,达成所有参与方都满意的结果。相关政府部门和专业委员会也有责任保护这些资源。他们需要制定有效的管理计划,防止资源被过度使用。在新西兰,许多事情都是让利益相关者参与讨论并确保计划得以合理实施,从而避免资源过度使用。这凸显了管理和政策制定的重要性。

LAJ:作为IFLA的主席,您主要倡导和推动的工作领域是什么?在任期内您可能会考虑什么?您认为IFLA近期的优先事项是什么?

Marques:作为唯一代表注册风景园林师的非政府组织,IFLA有责任让风景园林师的声音在全球范围内被听见,并发展为一个值得信赖的合作伙伴。我认为,一个优先事项是IFLA的管理团队需要强化与联合国及其附属机构、联合国教科文组织、国际古迹遗址理事会、人类住区规划署、世界自然保护联盟、联合国粮食及农业组织、国际城市健康学会、世界卫生组织、国际建筑师协会以及国际城市与区域规划师学会等组织的交流和合作。我们需要明确:谁是我们的合作伙伴?我们应与谁进行对话?我们如何确保他们理解风景园林的重要性?

另外,我们需要对IFLA的成员提供全面支持。IFLA现有78个国家和地区的成员协会和超过50 000名成员,预计全球约有100万名风景园林师。大多数成员反映,提升风景园林师这一职业在当地政府和机构中的知名度和认可度是一个核心问题。因此,我们正在努力探索如何在地方语境下支持我们的成员,使他们能在当地真正施展影响力。

这基本上涉及两个相互对立但同样重要的层面:一是在国际层面上与国际组织、机构的合作,二是在地方层面上对成员的支持。

LAJ:您认为IFLA是如何在全球范围内促进风景园林师教育?

Marques:IFLA作为全球最早确立风景园林教育标准的非政府组织之一,其地位及任务对于风景园林学科的飞速发展尤为重要。我们必须致力于创新,以适应时代的变迁。我们的教育委员会代表涵盖全球各主要地区,致力于建设各地区的教育组织。欧洲有风景园林学校理事会,北美有教育工作者委员会,中国的教育项目可能是世界上最大的,我们正在努力与中国风景园林学会建立更紧密的联系,推进风景园林师教育。

通过吸纳具有共同理念的人参与学科讨论,我们能够了解关注的主要趋势,从而为全球任何一所大学提供有关风景园林专业发展方向的指导。

当前,如何将技术,特别是人工智能,融入我们的课程,成为一项重要议题。人工智能的最新发展将对我们未来的教学方式产生深远影响,甚至可能改变风景园林学科或职业形态。尽管如此,学科的核心内容如生态重要性和人文重要性等将保持稳定。因此,风景园林教育的未来仍有许多问题需要我们去解决和探讨。

LAJ:人工智能近期发展显著,特别是ChatGPT的发布对各行各业都有很大的影响。您认为人工智能对风景园林将产生什么影响?

Marques:人工智能作为一个新兴的领域,现在讨论其具体影响尚属过早。然而,我们可以确定的是,它将改变我们的工作方式。回顾几十年前,当地理信息系统(GIS)初露头角时,人们曾惶恐不安,以为它会取代风景园林师和规划师,但事实并非如此。同样,人工智能并不能替代风景园林师,因为它无法理解和体验空间。比如,如果你让一个人工智能系统,如ChatGPT,来描述其对某个公园的感觉,它将无法提供具体的空间体验感。这是人工智能的局限,仅有人类才能将行为和体验整合进设计中。

尽管如此,人工智能正逐渐成为我们的重要工具,它可以帮助我们进行头脑风暴、可视化概念,并在项目过程中适应它,这可能会优化设计结果。因为它能够快速地提供一套场景,简化一些传统上需要很长时间才能完成的工作。

新事物的出现总会引发人们的紧张和不安,长期影响尚无人能知晓,但这是我们前进过程中的一个环节。就像我们曾经适应了CAD、GIS等新技术一样,我们也会适应和接纳人工智能的出现。

LAJ:风景园林师的就业情况因国家而异。10年前,风景园林师在中国是一个非常热门的职业选择,但由于社会经济问题,近年来这个趋势已经逐渐放缓,请问您如何看待这个问题?

Marques:风景园林师的需求和地位因地域和国家而有所不同。在IFLA的全球视野中,风景园林师的需求非常旺盛,我们难以找到足够多的毕业生来满足这个需求。显然,风景园林师的角色非常符合21世纪的课题,如果你理解了城市环境和绿化对人类健康和福祉以及应对未来气候变化的重要性,你就会意识到风景园林师的工作极其重要。

然而,我们的行业仍被一些陈旧的观念所束缚,如源于18世纪的风景园林被视为花园和园艺设计的概念,我们需要改变这种观念。我经常告诉学生,如果你在专业生涯中花2%的时间设计花园,这已经算是很多了,因为这是许多人都能做的事情。现在,仍然有人把我们误解为只是与花园打交道的职业,但是当人们真正理解风景园林师的工作范围和潜力时,他们会被其深度和广度所震撼。随着城市的持续发展,我们需要以可持续的方式应对这种增长,为人们提供更好的生活质量。

在中国,风景园林师的职业地位可能不如10年前那么受欢迎,我不确定它是否会重新成为一种迫切需要的职业。然而,我们作为从业者需要展现出更大的积极性。与通常充满自信的建筑师相比,风景园林师有时会显得过于内敛。我们需要更加积极和自信,去展示我们的工作。这需要更多像你一样在教育领域投身多年的人,不仅在大学里,也在社区和政府机构里提高人们对我们工作的认识。在政府层面上产生影响并推动改变是至关重要的,这样高层次的改变就会逐渐影响到基层。因此,如果我们更加重视风景园林教育,就可以吸引更多新鲜血液加入这个行业,同时也应尝试影响更高层次的决策者和政府机构,因为他们真正的有权力推动变革。

LAJ:今天的风景园林师要处理复杂且现实的问题,比如气候变化。我们也需要更多的技能。您认为我们与城市规划师的关系如何?

Marques:我们需要与规划师紧密合作,因为我们正在尝试实现一些重要的变革。规划师在努力理解系统的复杂性,特别是在经济层面,同时也牢牢掌握立法、政策制定以及发展风景园林的重要性。作为风景园林师,我们能够让规划师理解生态和自然系统。通过与规划师的合作,我们可以从他们身上学到很多东西,例如在立法和政策制定方面变得更加积极。

城市环境的未来在很大程度上取决于这种合作,甚至超过与建筑师的合作。规划师和风景园林师知道如何组织一个城市,并在此基础上考虑建筑层面的问题。我们应该以这种目标模式为导向,而不是让建筑师先设计建筑,然后将剩下的一切交给风景园林师处理。

新西兰与中国在规划方式上存在不同。新西兰的规划者主要关注决策发展而不是专业规划。在新西兰,大部分的空间规划都是由风景园林师或建筑师进行。规划者的角色是确保政策制定、经济发展、基础设施等各类问题得到解决。尽管我们需要风景园林师和规划师在最高水平上进行紧密合作,但与这个现实还有一段距离。我们只能期盼未来会有所改变,并不断努力达成更加紧密的协作。

LAJ:您对即将进入风景园林设计行业的从业者或即将进入该领域学习的学生有什么建议?我们在工作和学习中最不应该失去的品质是什么?

Marques:保持好奇心并对外部世界怀有热情是至关重要的。在进入风景园林行业前,你需要积累大量关于自然、生态和系统的专业知识和相关背景信息。这一宝贵的知识体系将确保你在全球任何地方都能从容地应对设计工作。

我们不仅是与自然相处,我们更是为人们做设计,与他们紧密合作。因此,风景园林设计不仅要求学生掌握自然相关的知识,还要求学生了解当地的社会背景和文化背景、熟悉人们的生活环境。所以,我强烈鼓励学生保持好奇,对学习充满渴望,去探索不同的环境,去理解不同的人群,体验不同的大学。世界无疆界,学生们可以走向任何地方,去学习新的文化,掌握新的语言,和研究前沿的风景园林设计方法。这种多元的经验将丰富他们的视野,帮助他们成为更优秀的风景园林师。

LAJ:非常感谢您接受本次采访!

Marques:不客气。我很荣幸。

图片来源(Sources of Figures):

访谈人物图片由深圳大学建筑与城市规划学院提供;图1、2由马奎斯主席提供。

(编辑 / 李清清)

采访者简介:

张柔然 / 男 / 博士 / 深圳大学建筑与城市规划学院副教授、硕士生导师 / 剑桥大学麦克唐纳考古研究所副研究员 / 国际古迹遗址理事会国际文化旅游科学委员会副主席 / 中国风景园林学会青年工作委员会副主任委员 / 研究方向为文化与自然遗产规划与管理、风景园林规划与设计、国家公园、文化旅游

译者简介:

陈欣 / 女 / 深圳大学建筑与城市规划学院在读硕士研究生 /研究方向为风景园林与生态环境规划设计

胡嘉鸿 / 女 / 深圳大学建筑与城市规划学院在读硕士研究生 /研究方向为风景园林与生态环境规划设计

校者简介:

王长宏 / 男 / 硕士 / 北京北林地景园林规划设计院有限责任公司设计五院二所所长 / 研究方向为风景园林规划设计与城市更新

ZHANG R R.The Human-Land Relationship in the Landscape: Interview with Doctor Bruno Marques, President of the International Federation of Landscape Architects[J].Landscape Architecture, 2023, 30(12): 12-21.

The Human-Land Relationship in the Landscape: Interview with Doctor Bruno Marques, President of the International Federation of Landscape Architects

Interviewer: ZHANG Rouran Translators: CHEN Xin, HU Jiahong Proofreader: WANG Changhong

Interviewee:

(NZ)Bruno Marques, Ph.D., is president of the International Federation of Landscape Architects(IFLA), the associate dean of the Faculty of Architecture and Design Innovation, Victoria University of Wellington, and the founders of the research lab “Therapeutic + Rehabilitative Designed Environments”.His research focuses on Māori tribal culture, therapeutic landscapes,community-based participatory design, and urban healthy streets.

©BeijingLandscape ArchitectureJournal Periodical Office Co., Ltd.Published byLandscape ArchitectureJournal.This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license.

Dr.Bruno Marques currently serves as president (from September 2022 to present) of the International Federation of Landscape Architects(IFLA), and associate dean of the Faculty of Architecture and Design Innovation, Victoria University of Wellington.His research focuses on community health and well-being, Māori tribes,therapeutic landscape, and community-based participatory landscape design approaches and practices.He is also one of the founders of the research lab “Therapeutic + Rehabilitative Designed Environments/Taiao + Tumahu” (TRDE).This multi-disciplinary and multi-institutional research lab is dedicated to developing evidencebased research to demonstrate how architecture,landscape and technology can support relevant healthcare practices.In April 2023, President Marques was invited to participate in the 13th Annual Meeting of the Chinese Society of Landscape Architecture, as well as the“International Forum on the Frontiers of Landscape Architecture and the Youth Professional Forum on the Protection of Landscape Heritage on 4.18 International Day for Monuments and Sites” hosted by the Youth Working Committee of the Chinese Society of Landscape Architecture.Landscape Architecture Journal Periodical Office had the honor to interview President Marques, discussing in depth the human-land relationship in landscape.

LAJ:Landscape ArchitectureJournal Marques: Dr.Bruno Marques

LAJ: In the context of globalization, how do you see the disruption of the human-land relationship in landscape?

Marques: I think we have caused a lot of damage to our land.We have heavily modified it for many different reasons, mainly for food production and economic gain.And I find that we are trying to fix those mistakes, turn back to find a much better balance with nature and have nature around us, we are not solely looking at nature from an economic gain perspective, but rather pursuing a harmony with it.In many countries, landscape architecture is really becoming much more important than in the past, we’re trying to address the mistakes of the past.The issue of climate change, for example, just keeps us reminding that we need to address more mistakes.And I think we need landscape architects to be really at the forefront of those discussions and solutions.

LAJ: You understand Māori culture very well.Māori traditional values are rooted in the natural landscape they inhabit, giving birth to a complex system of indigenous knowledge.How do you see the interaction between Māori people and landscape, and Māori nature and culture?

Marques: Māori culture is a collective culture.For them, the well-being of family unit and overall tribe is very important.The landscape is what defines “who they are” and becomes their identity card.When you go into a meeting with Māori tribe, they would never introduce themselves with their names, they don’t start with that.Instead, they start by identifying the mountains,rivers, lakes, and seas that belong to them, along with their tribe and family.Actually, the given name is the last thing they tell you (Fig.1).It automatically establishes a very strong grounding on the landscape, and it also gives you the geolocation where they come from.It explains the very strong connection they have with a particular piece of land.That’s the environment defines “who they are” and defines their existence.

Through this connection, we learn much more about how to manage and respect the land,which is very different from the western understanding.Māori people have passed on knowledge through the generations, and integrate information about land, as well as the concept of proper land stewardship, into their identity.However, this knowledge about land and identity is mainly transmitted orally rather than in written records.This knowledge intricately linked with land management and protection.If there’s no land,there is no Māori culture.I think their behaviors are culturally driven.For them, culture, landscape and people are intertwined (Fig.2).Even within the same country, if people are moved from the northern lands where their ancestors lived and settled in the south, they will struggle because it’s not their land, and they cannot find the identity connected to the northern land.

I think it’s interesting that it relates to your first question.With the advent of globalization, it seems like we need to strengthen individual and international connections.However, I think it’s time to realize the importance of regionalism and return to the region as well as what is specific to the place.Because we are just always influenced by the environment information around us, we almost like to go back to the beginning, and the primordial existence of human-environment relationship in a certain environment.

1 The natural landscape mentioned by Māori at the seminar

LAJ: Today, climate change is affecting the whole world, international relations are changing rapidly, globalization is accelerating,and our lifestyle is different from the past,which sometimes lead to the decline of local culture and experience.In view of this, how should we restore or revive our local culture and knowledge?

Marques: Local knowledge is a valuable resource that is constantly evolving and changing,and landscape architects have a responsibility to ensure its inheritance and protection from generation to generation.Numerous local traditions and forms of knowledge face the risk of disappearing due to a lack of written documentation.Therefore, the implementation of appropriate protective measures is imperative in order to preserving these local cultures.

In both Australia and New Zealand, we come across numerous successful instances where indigenous knowledge has been utilized to address issues related to climate change and the mitigation of invasive species.For instance, in Australia,Indigenous inhabitants manage the proliferation of invasive species by employing controlled burning practices.Similarly, in New Zealand, Māori tribes have maintained traditional techniques for managing rainfall and flood occurrences.These instances underscore the vital role of indigenous knowledge in effectively addressing environmental challenges.

2 Māori involve the “whole of landscape” approach known as “from mountains to sea”

As landscape architects, we shoulder the responsibility and obligation of applying our professional expertise to safeguard and perpetuate indigenous cultures, while simultaneously tackling challenges such as climate change and invasive species.Our objective is to design landscapes that are distinctly representative of their local context and relentlessly strive towards a more promising future.Through collaboration with local communities, we gain a deeper appreciation for and understanding of their customs and wisdom,which we then integrate into our designs, thus making a contribution to the preservation of indigenous cultures.

LAJ: How do you think we can incorporate indigenous knowledge into landscape design? Could you provide some specific examples?

Marques: Landscape architecture design should evoke a sense of local identity, enabling people to connect with the unique characteristics of the region.When looking out of the window of the hotel, these buildings lack distinct local features and could exist anywhere in the world.Just looking at the buildings, it’s difficult to discern whether we are in China, the United States, Singapore, or Sweden.Hence, in landscape architecture design,it’s important to consider how to apply indigenous knowledge to address specific local issues or showcase local traits.For instance, the indigenous knowledge and problem-solving strategies in Shenzhen might not be suitable for use in northern China, as the environmental context and landscape are different.Therefore, as landscape architects, it’s essential to establish closer connections with the local community, exploring more interesting solutions that integrate local knowledge, and effectively showcase the region’s distinctiveness.

LAJ: What do you think that landscape with a strong human-land relationship can foster a sense of belonging and identity? And how can a sense of place be shaped in landscape planning and design?

Marques: By creating solutions tailored to the specific context we are in and employing design language, materials, and vegetation, a sense of local identity and community belonging can be given to people.They will feel familiar with it and identify with the surrounding environment.Instead, being in a totally foreign environment where they just feel that the materials, patterns, traditions, or customs are not really from this specific area, and they may feel that they don’t really belong here and lose their sense of identity or belonging.Thus,incorporating local characteristics in design, using local materials, patterns, and traditions, can strengthen the bond between users and surroundings, fostering a sense of community belonging.This design language and elements generate an emotional resonance with the environment, encouraging people to identify with and integrate into the community.

LAJ: Your research area relates to therapeutic landscape, focusing on the mental, physical and social well-being of disadvantaged individuals.In your research on urban healthy streets, you’ve noted the inclusivity of streets.These align well with this year’s IFLA sub-theme, “Leave No One Behind”.So what do you think about this theme?

Marques: Different types of people view the natural and built environment differently, because they all connect to things differently.For instance,from a western perspective, people put on their gym shorts and running shoes, and go to the waterfront to have a run for fitness.However, the pattern does not apply to other cultures, which don’t feel that you should go for a run in the waterfront with strangers.As an example, my grandparents and grandchildren often take walks in the family room, considering it more crucial for exercise and fitness than just running along the waterfront by themselves.

I think the primary goal of studying health streets is to make people realize the value of street environments and willingly engage with them.Those who probably have lower mobility feel that the streets need to be better designed to ensure universal access.The issues like ramps and stairs tend to be problematic for people, especially for elderly individuals with reduced lower body strength, as such designs can prevent issues like falls and fractures.Therefore, paying close attention to everyday details, especially in street design, is essential to ensure the accessibility of public spaces.

From a cultural perspective, we should contemplate how design can create spaces where people can feel that their own cultures are represented and feel comfortable within it.While crafting a sense of community and place,incorporating symbols, components, materials, and elements from the local culture into urban space design is crucial.By employing these cultural elements, we can instill a sense of belonging and unity among residents, reflecting their culture and identity.

LAJ: In order to shape a better humanland relationship in landscape, you mentioned that landscape design should shift from a“designer project” to a “community project”.What do you think are the values and necessities of community-based participatory landscape design?

Marques: I think there are many architecture and landscape architecture projects which are often designed by someone who probably lack genuine interaction with the community.In other words,designers spend significant time crafting designs that might be signed by star architects or star landscape architects and become a brand, but they may not align with the actual needs of the community.I think the successful projects are those that really showcase different design approaches, involve people in those discussions and incorporate their input into the design process,rather than designers becoming disconnected from people and coming up with a solution that might not be what they’re looking for.

During interactions with the community,people may point out commonly used areas, such as spots requiring shade.Designers should explicitly preserve these areas instead of placing facilities there that will never be used.Alternatively,people might mention linear paths formed through use.Designers should retain these pathways instead of forcing users to take detours, as they will ultimately seek other shortcuts.When engaging with the local community, people will provide information that designers might not be aware of,because they have the experience of using these spaces and understand which areas should be retained or relinquished.

Community involvement is essential, whether during site analysis or conceptual design stages.Throughout this iterative process of communication, they will provide us with very meaningful feedback.Being immersed in the project, they’ll understand why we are doing it and how they can use it.In contrast to presenting a design proposal directly to the community, what I refer to as a “designer’s project,” a “community project” that involves public participation incurs higher costs but ultimately yields more sensible outcomes.

LAJ: In your community-based participatory landscape design projects, what impressions have students left on you throughout their involvement? To encourage students to value the relationship between human and land in landscape, what aspects of landscape architecture education should we pay more attention to?

Marques: When students first attempt this approach, they often feel discomfort, because they feel fearful and discomfort to talk to strangers.So initially, when I tell them to break from the norm,to engage in projects in new ways, and to talk to different groups and age ranges, they often resist.But once they do it, they witness the positive transformations this approach brings.

Taking an example from a student-involved design project I initiated in early March this year, I took the students to stay with the Māori tribe for about a whole week.Initially, they actually didn’t enjoy going to engage with them.But as they went around to explore the area and interacted with the local people, they realized that they got so much valuable information that they couldn’t just obtain from any other sources.This discovery fueled their inspiration and sense of responsibility in advancing the project because they realized the locals had invested time and knowledge, and they felt obligated to drive the project forward and find the best solutions.

Although it definitely takes more time than the traditional projects, I think it’s crucial for students’ growth.Because as we go into practice,we won’t work alone by ourselves, we’ll collaborate with other landscape architects or professionals, we need to interact with clients and communities.With deepening exposure and practice in this approach, I believe that students’ experiences will become more enriching, and their design abilities will be enhanced.And I think it’s a positive experience and outcome.

LAJ: The conservation, management and development of heritage often involve complex issues of local communities and indigenous people.What do you think about the relationship between local communities or indigenous people and heritage conservation and development?

Marques: We need to strike a balance.From my experience working with indigenous people,they are very proud of their culture and traditions and want others to learn about and respect them.The culture and traditional extremely fascinating,when people gain knowledge about these cultures,they learn to appreciate and respect them.However, there’s a fine line between appreciation and mass tourism, which can exploit those resources and landscapes, potentially causing even more damage.

If we involve indigenous communities in these discussions and develop reasonable plans to balance exposure to their culture and protection of natural resources, we can probably find an outcome that satisfies both parties.It’s also the responsibility of the local councils and original agencies to ensure that these resources are protected and preserved.They need to implement effective management plans to prevent the overuse of resources and the influx of large numbers of visitors to these places.In New Zealand, many of these discussions occur directly with the tribes.It involves bringing the stakeholders on board for these discussions and ensure plans are in place to prevent overused.It largely revolves around effective management and policy creation.

LAJ: What are the main areas of work that you advocate and promote as president of IFLA? What might you consider during your tenure?And what do you see as the priorities of IFLA in the near future?

Marques: As the only non-governmental organization representing enrolled landscape architects, IFLA has a responsibility to ensure our voice is heard globally and to evolve into a reliable collaborative partner.I think one of the priorities is that IFLA’s management team need to strengthen communication and collaboration with international organizations, including the United Nations (UN) and its sub-agencies, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), the UN-Habitat, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations(FAO), the International Society for Urban Health(ISUH), the World Health Organization (WHO),the International Union of Architects (UIA), the International Society of City and Regional Planners(ISOCARP), among others.We need clarity: who are our partners? Who should we be talking to?And how can we make sure that they understand the importance of landscape architecture?

The other aspect is to provide support to IFLA’s members.IFLA has 78 national and regional member associations and over 50,000 members.It is anticipated there are approximately a million landscape architects worldwide.One of the key issues that many members tell IFLA is to enhance the visibility and recognition of the landscape architects within local governments and agencies.Therefore, we are actively exploring how IFLA can support our members locally, so that they can actually make a difference locally.This essentially involves two contrasting yet equally crucial levels: international collaboration with organizations and institutions, and local-level support for members.

LAJ: How do you think that IFLA is promoting landscape architect education globally?

Marques: IFLA as the world’s one of the earliest establishments of landscape architecture education standard of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), its status and the task to cope with the rapid development of landscape architecture discipline is particularly important.We must be committed to innovation, so as to adapt to the changes of The Times.Our Education Committee represents various major regions around the world and is dedicated to building educational networks in different areas.We have the European Council of Landscape Architecture Schools in Europe (ECLAS), the Council of Educators of Landscape Architecture in North America (CELA), and the recently created American Council for Landscape Architecture Schools in the United States.We are also present in China, which likely has the large number of education programs in the world, and we’re striving to forge stronger ties with Chinese Society of Landscape Architecture (CHSLA) and the Education Committee to promote the landscape architect education.

By bring like-minded people into these discussions, we can stay abreast of the trends we should be focusing on.As such, we can provide guidance to any university in the world regarding what should be taught in Landscape Architects programs.

One of the key issues at present is how to integrate technology, especially AI into our curriculum.AI will largely determine our future teaching methods and may even change the shape of the landscape architecture discipline or profession.However, the core business will remain the same in terms of ecological importance, human importance, and so on.There are issues that the discipline will still need to address in the education of future landscape architects.

LAJ: The significant development of AI,particularly the release of ChatGPT, has had a significant impact on various industries.What do you think of the impact of AI on landscape architecture?

Marques: It’s too early to see the impact, as this is quite a new development.But it will change the way we do things.I remember some decades ago, when GIS became popular, people had moments of panic, thinking it was going to replace all landscape architects and planners.But it didn’t.AI will not be replaced us as designers because AI cannot comprehend the experience of space.If you were to ask an AI like ChatGPT how it feels about a certain park, it wouldn’t be able to describe the experience.Such experiences can’t be effectively conveyed by artificial intelligence; that’s the limitation.However, we can incorporate the experiential and behavioral aspects into our designs.

Meanwhile, AI is becoming an important tool that we can use for brainstorming ideas, visualizing concepts, and adapting it into project development,which might enhance the design outcomes.Because it is able to quickly provide a set of scenarios, and simplify processes that usually take a long time.

It’s just a matter of adjusting.People often panic when there is change, because they are used to doing things a certain way and then suddenly something new is introduced.No one knows the long-term impact of it yet.But I think it’s very positive.Just like everything else we do, such as CAD and GIS, and everything else, we will become accustomed to this as well.

LAJ: The employment of landscape architects varies from country to country.Landscape architect was a very popular career choice in China 10 years ago, but the trend has been gradually declining in recent years due to social and economic issues.What do you think of this?

Marques: As you said, it varies from country to country.In the global field of vision of IFLA,landscape architects are in high demand.There aren’t enough graduates out there; we can’t find them.Undoubtedly, the role of a landscape architect aligns well with 21st-century concerns.If you grasp the significance of urban environments,the promotion of human health and well-being through green spaces, and the crucial response to impending climate change, you’ll recognize the profound importance of the landscape architect’s role.

At the same time, we still carry baggage from the past, being associated with the idea of gardens and gardening, which is an 18th-century interpretation of Landscape Architecture.We need to move away from that.I generally tell my students that if they’re going to spend 2% of their professional time designing gardens, that’s going to be quite a lot because so many people can do that.There are still some very strong stereotypes that we are a profession dealing with gardens.But once the general public comprehends the scope and potential of our profession, they are often amazed by its depth and breadth.As our cities continue to grow, there will still be a need for us to address that growth and make cities more sustainable, providing a better living environment for people.

While it might not be as popular in China as it was 10 years ago, I’m not sure whether it will become an urgent need of professional again.However, we need to be a little more aggressive.Comparatively, landscape architects are often very modest.We sometimes have an inferiority complex when compared to architects, who are typically very assertive.We need to be just as assertive, if not more so, and show the world what we do.This necessitates the involvement of more individuals,akin to your years of commitment in the education sector, to enhance awareness about the work we engage in.This awareness-building effort spans not only within academic institutions but also extends into local communities and governmental bodies.Exerting influence at the governmental level and driving transformative measures is of paramount importance, as such top-down alterations will gradually percolate to the grassroots.Therefore, by according greater emphasis to landscape architecture education, we can not only attract a fresh influx of talent into the field but also endeavor to sway higher echelon decision-makers and governmental entities, given their authority to effect substantial change.

LAJ: Today, landscape architects need to deal with more complex and realistic problems, such as climate change, which entails the mastery of more skills.What do you think about the relationship between landscape architects and urban planners?

Marques: We need to collaborate closely with urban planners as we are endeavoring to enact significant reforms.Urban planners are engaged in comprehending the intricacies of systems,particularly on economic levels, while also holding a firm grasp of legislation, policy formulation, and the significance of landscape architectural development.As landscape architects, we bring an understanding of ecological and natural systems to the table.Through collaboration with urban planners, we have opportunity to learn from them,such as becoming more proactive in legislative and policy-making endeavors.

The future of urban environments largely hinges upon this collaboration, even surpassing that with architects.Planners and landscape architects understand how to organize a city and subsequently address architectural concerns.We should be guided by this goal-oriented approach,rather than having architects design buildings first and then entrusting landscape architects with everything else.

What distinguishes New Zealand from China is that New Zealand planners are primarily concerned with policy development, rather than being heavily involved in spatial planning.Much of the spatial planning is conducted through landscape architecture or architecture.We encounter a distinct scenario where planning as a profession isn’t as mature, and the spatial planning of cities is overseen by architects and landscape architects.Planners are present to ensure that policy-making, economics, and other facets such as infrastructure are duly addressed.While we require landscape architects and urban planners to collaborate closely at the highest level, there is still a gap between this aspiration and reality.We can only hope for future changes and consistently strive to achieve a more seamless cooperation.

LAJ: Do you have any advice for students who are about to enter the landscape design industry or to study in this field? And what is the most important quality that we should not lose in work or study?

Marques: Embrace your curiosity for the world beyond.Our profession equips you with the ability to comprehend the workings of nature,ecology, systems, and layers of information.I believe this skill set is invaluable and enables you to operate worldwide.

Simultaneously, our engagement isn’t confined to nature alone; it extends to crafting environments for people’s closer interaction with it.This transcends nature’s scope, as students must grasp the local context and the individuals who inhabit these spaces.Thus, I strongly urge you to nurture your curiosity, maintain a thirst for learning, explore diverse environments,comprehend various cultures, and embrace the diversity of university experiences.

The globe is your canvas.Students can venture anywhere their hearts desire.They can immerse themselves in novel cultures, languages,and varied methods of practicing landscape architecture.This will undeniably enrich their experiences and refine their skills as landscape architects.

LAJ: Thank you so much for this interview!

Dr Marques: You’re welcome.My pleasure.

Sources of Figures:

Portrait of President Marques is provided by School of Architecture and Urban Planning, Shenzhen University;Fig.1-2 are provided by President Marques.