Vitamin D therapy in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Mohammad Hassan Sohouli · Fatemeh Farahmand · Hosein Alimadadi · Parisa Rahmani · Farzaneh Motamed ·Elma Izze da Silva Magalhães · Pejman Rohani

Abstract Background There is some evidence for the role of vitamin D deficiency in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease(IBD) in the pediatric population.However,the results are contradictory.Therefore,we have conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluated the effect of vitamin D on pediatric patients with IBD.Methods We carried out a systematic search in databases from inception until 20 January 2022.We included all relevant articles that evaluate the efficacy and safety of vitamin D on disease activity,inflammatory factors,and vitamin D and calcium levels in pediatric patients with IBD.Random effects models were used to combine the data.The main outcomes were then analyzed using weight mean difference (WMD) and respective 95% confidence interval (CI).Results Fifteen treatment arms met the eligibility criteria and were included.Pooled estimates indicated that intervention with vitamin D has a significantly beneficial effect on 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 [25(OH) D3] (pooled WMD of 17.662 ng/mL;CI 9.77–25.46; P <0.001),calcium (pooled WMD of 0.17 mg/dL;CI 0.04–0.30; P =0.009),and inflammatory factors including C-reactive protein (CRP) (pooled WMD of −6.57 mg/L;CI −11.47 to −1.67; P =0.009) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate(ESR) (pooled WMD of −7.94 mm/h;CI −12.65 to −3.22; P =0.001) levels.In addition,this effect was greater for vitamin D levels at doses greater than 2000 IU,and when follow-up duration was more than 12 weeks.Conclusion This study showed that vitamin D therapy can have a significant and beneficial effect on 25(OH) D3,calcium,and inflammatory factors in children and adolescents with IBD.

Keywords Disease activity index · Inflammation · Meta-analysis · IBD · Pediatric · Vitamin D

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is characterized by a gastrointestinal disorder in the form of relapsing and remitting chronic inflammation that includes as main subgroups Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) [1].Evidence has shown that in the United States and Canada,the prevalence of IBD in children is about 10 per 100,000 children and is increasing [2].There are hypotheses about the role of the interaction between the immune response,environment and intestinal microbiota in genetically predisposed subjects in the development of this disease [3,4].Among environmental factors involved in this disease are dietary factors [5].Several studies have reported growth disorders,poor weight gain and micronutrient deficiencies in a pediatric population with IBD [1].

Vitamin D is one of the most regular micronutrients lacking in these patients [6].There is even some proof that low levels of this nutrient are a risk factor for IBD [6].In some cases,it is hazy whether this low level is the reason or an outcome of the sickness.Vitamin D,as a fat-solvent nutrient,has been indicated to play an expected part in the function and metabolism of minerals and bones,as well as in the regulation of innate and adaptive immune system [7–9].In addition,vitamin D plays several important functions in modulating inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines,T lymphocytes,tumor necrosis factor α,interferon γ,and prostaglandin synthesis [8,10,11].Given the involvement and role of these factors in IBD,the potential effects of vitamin D in activity and development of this disease have been considered by scientists.Although some studies have shown the beneficial performance of this vitamin in IBD in pediatric patients [12–15],some studies have not observed the specific performance of this supplement in these patients[16,17].

Despite available evidences,there is still no comprehensive evidence of the effect of this vitamin in creating optimal serum levels of vitamin D and positive function in pediatric patients with IBD.Clarification of vitamin D’s function will benefit for using an effective therapeutic approach.Subsequently,in the current review we led a meta-analysis to research the expected impacts of vitamin D on disease activity index,inflammatory factors,and vitamin D levels in pediatrics with IBD.In addition,the effect of follow-up study time and dose of vitamin D supplementation on these factors was investigated by performing a subgroup analysis.

Methods

Search strategy

This study was reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis(PRISMA) guidelines [18].PubMed/MEDLINE,Web of Science,SCOPUS,and Embase information bases were looked at from inception until 20 January 2022,with no language or time limits.Medical subject headings (MeSH) were considered for the search in the data sets,as follows: (“vitamin D” OR “ergocalciferols” OR “25-hydroxyvitamin D”OR “25 hydroxyvitamin D” OR “calcifediol”) AND (“colitis ulcerative” OR “crohn disease” OR “inflammatory bowel diseases”) AND (“Child” OR “Adolescent” OR “Pediatrics”OR youth* OR teen*).

Eligibility criteria

Two analysts,autonomously,avoided repeated articles and afterward distinguished and looked into articles by understanding titles,abstracts,or the full text of the investigations.Afterwards,the investigations were chosen according to following standards: (1) studies with follow-up of 1 week or more,including prospective,retrospective,and clinical trials;(2) studies led by participants under 18 years aged who went through various portions of vitamin D treatment;(3) data of the primary [Pediatric Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (PCDAI) or Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index(PUCAI) score,25-hydroxyvitamin D3 (25(OH) D3),serum calcium] and secondary [C-receptive protein (CRP),erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR),and parathyroid chemical(PTH)] results at the baseline and after treatment of vitamin D.In situations where the study assessed the variables at more than one subsequent time,the greatest or latest subsequent time was thought of.We rejected animal studies,systematic reviews,studies with less than one week of follow-up,repeated studies and uncertain information that did not get feedback after contact with creators.

Data extraction and quality assessment of studies

Selected studies,information was extracted by two independent researchers.Data required for this study included:mean and standard deviation (SD) of PCDAI/PUCAI score,25(OH) D3,serum calcium,CRP,ESR,and PTH at the baseline and after vitamin D therapy,authors,year of publication,country,number of participants,percentage of male participants,mean age (years),as well as doses of supplementation,type of IBD,study design,and follow-up duration of the intervention.The quality of the studies included was assessed independently by two authors through to the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale [19].

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed utilizing RevMan 5.3(The Nordic Cochrane Center,Copenhagen,Denmark)and STATA forms 12.0 (Stata Corp,College Station,TX,USA) programming.To work out the weight mean differences (WMD),the mean and SD of factors at the baseline and after vitamin D treatment were extricated from each article and afterwards the evaluations were applied for each study utilizing a random-effects model.In situations where the information was present in an alternative configuration,standard computations were applied to get the mean and separate SDs [20,21].For concentration revealed by standard error of the mean (SEM),SDs were acquired with the equation: SD=.Heterogeneity between studies was assessed through Q Statistics and I-squared (I2).I2 upsides of 0% to 25%,26% to 50%,51%to 75%,and 76% to 100% percent were named immaterial,low,moderate,and high heterogeneity,individually[22].Possible origins of heterogeneity were analyzed through subgroups examinations in light of portions of vitamin D supplementation and length of study follow-up.A sensitivity analysis was applied.Publication bias was assessed utilizing the Begg tests [23].

Results

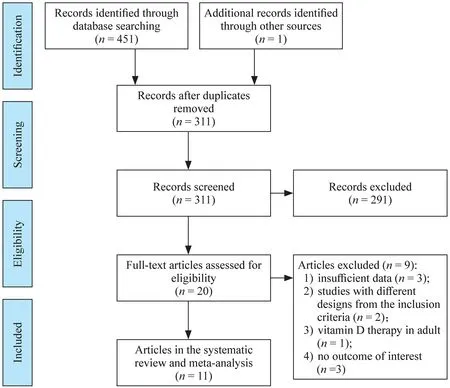

Diagram of inclusion is displayed in Fig. 1.In the wake of looking through the data sets,451 outcomes were chosen (one article recognized through different sources),with 311 reports staying after the elimination of copy studies.Then,in the wake of assessing the theoretical or title,291 articles were erased because of the inconformity to critera.Subsequent to recovering the full text of the leftover 20 articles,nine articles were erased because of lacking information (n=3),different study critera (n=2),vitamin D treatment in the grown-up (n=1),and absence of a result of interest (n=3).Finally,11 [12–17,24–28]studies with 15 treatment arms met the eligibility criteria and were included in our analysis.

Fig.1 Flow chart of the included studies,including identification,screening,eligibility and the final sample included

Study characteristics

Table 1 shows the attributes of the pooled articles.Four examinations have been led in the Americas,two investigations in Oceania and one concentrated in Africa,and the rest in Europe.Included examinations were distributed between the years 2007–2020.In addition,all chosen studies were performed on two genders and the level of males in the examinations varied from 41% to 74%.The subsequent intercession of the examinations was between 2 and 48 weeks.The mean age of the participants at the gauge fluctuated somewhere in the range of 12.4 and 15.6 years.The vitamin D enhancement utilized in the examinations went from 400 to 30,000 IU,and the concentration of vitamin D in serum was 15.72–29.32 ng/mL.Baseline levels of PCDAI/PUCAI scores were accounted for in four examinations,with a most extreme score of 5 and 34.5.Consequences of the quality evaluation of the examinations are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2 Risk of bias assessment according to the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale tool

Meta-analysis results

Pooled estimates from the random-effects model demonstrated that CRP [pooled WMD of −6.57 mg/L;95%confidence interval (CI) −11.47 to −1.67;P=0.009] and ESR (pooled WMD of −7.94 mm/h;CI −12.65 to −3.22;P=0.001) decreased significantly after vitamin D therapy compared with before intervention.In addition,it was observed that vitamin D therapy significantly increased 25(OH) D3 (pooled WMD of 17.62 ng/mL;CI 9.77–25.46;P<0.001) and calcium (pooled WMD of 0.17 mg/dL;CI 0.04–0.30;P=0.009).In any case,no huge change was seen in PCDAI/PUCAI score (pooled WMD of −7.92;CI−17.60–1.76;P=0.109) and in PTH levels (pooled WMD of −2.74 pg/mL;CI −5.65 to 0.16;P=0.062).Critical heterogeneity was seen among the examinations for all factors (CochranQtest,P<0.001,I 2=99.7% for PCDAI/PUCAI score;CochranQtest,P<0.001,I2 =99.5% for 25(OH) D3;CochranQtest,P<0.001,I2 =98.8% for CRP;CochranQtest,P<0.001,I2 =99.0% for ESR,CochranQtest,P=0.028,I2 =60.2% for calcium;CochranQtest,P=0.001,I2 =72.2% for PTH) (Figs. 2 & 3 a,b,c,d,and e).

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup results showed that vitamin D therapy potentially caused a further increase in vitamin D levels during a follow-up period of more than 12 weeks and at doses greater than 2000 IU.Intervention with vitamin D was also shown to have a greater effect on calcium levels during the follow-up period of more than 12 weeks and on PTH in the intervention dose of more than 2000 IU.Further reduction of CRP also was observed after intervention with vitamin D at a dose ≤ 2000 IU.For other outcomes,subgroup results were not reported owing to the small number of articles in subgroups (Supplementary Figs.1–4).

Fig.2 Forest plot of changes in serum 25(OH) D3 levels (ng/mL) after vitamin D therapy. 25(OH) D3 25-hydroxyvitamin D3,WMD weight mean difference,CI confidence interval,ID identification

Fig.3 a Forest plot of changes in PCDAI/PUCAI scores after Vitamin D therapy. b Forest plot of changes in CRP (mg/L) after vitamin D therapy. c Forest plot of changes in ESR (mm/h) after vitamin D therapy. d Forest plot of changes in derum calcium(mg/dL) after vitamin D therapy.e Forest plot of changes in PTH(pg/mL) after vitamin D therapy. PCDAI Pediatric Crohn's Disease Activity Index,PUCAI Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index,ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate,PTH parathyroid hormone,WMD weight mean difference,CI confidence interval,ID identification

Fig.3 (continued)

Sensitivity analysis

To research the effect of each article on the pooled effect size for PCDAI/PUCAI score,25(OH) D3,calcium,CRP,ESR,and PTH,we removed every study from the examination in stepwise style.A leave-one-out responsiveness investigation showed the robustness of the outcomes (Supplementary Figs.5 and 6).

Publication bias

While assessing publication bias by visual review of the funnel plot,no proof for distribution inclination in view of Begg's tests was distinguished for PCDAI/PUCAI score(P=1.00),25(OH) D3 (P=0.343),calcium (P=1.00),CRP(P=0.764),ESR (P=0.734),and PTH (P=0.764) (Supplementary Figs.7 and 8).

Discussion

Vitamin D therapy has recently been used as a complementary therapeutic approach in line with other common medical treatments in many medical centers,and a beneficial effect has been observed in most clinical factors and even in the quality of life.

The results of the present study showed that vitamin D has a significant and beneficial effect on the level of 25(OH)D3,calcium,and inflammatory factors including CRP and ESR in pediatrics with IBD.In addition,this effect was greater for vitamin D levels at doses greater than 2000 IU,and follow-up duration of more than 12 weeks.To date,no systematic and comprehensive study has been published on the effects of vitamin D in pediatrics with IBD.However,several meta-analysis studies have been performed on the function of vitamin D in adult subjects with IBD.In a meta-analysis of studies with adults,including 16 clinical trials and observational studies,it was reported that vitamin D supplementation increased the level of 25(OH) D3 by 15.50 ng/mL (16 ng/mL in our study) and that this effect was greater at higher doses [7].Our results are in line with these results.Furthermore,our study showed that CRP was significantly reduced by 1.58 mg/L after vitamin D treatment.At last,we additionally showed that vitamin D supplementation in kids and youths with IBD is compelling in supporting vitamin D levels and is related to improving clinical and biochemical scores of sickness activity.Another review with 18 articles,incorporating 908 patients with IBD,showed that 25(OH) D3 levels were altogether higher in patients who got vitamin D than the benchmark group [29].Notwithstanding,dissimilar to our review,there was a tremendous distinction between the doses used in the report,which could be attributed to the number of articles included in each subgroup and also to the difference in inclusion criteria in this study compared to our study.In addition,no significant difference was observed in inflammatory factors including ESR and CRP between the two groups [29].According to our study,after supplementation with vitamin D,these factors decreased significantly after the intervention than before the intervention [29].In another meta-analysis in 2019,27 observational studies were included to investigate the relationship between vitamin D status and its clinical function in IBD [30].The outcomes showed that there was a significant association between low degrees of 25(OH) D3 with an expanded risk of the clinical capability of the disease,mucositis,and bad quality of life score.A methodical report likewise revealed that patients with gastrointestinal diseases,particularly patients with IBD,are more likely to be lack of vitamin D because of malabsorption,which can influence illness activity [31].A recent report by Papa et al.revealed a high commonness of lack of vitamin D in youngsters with IBD.Likewise,it was reported that lack of vitamin D is more serious in individuals with higher levels of inflammatory factors,lower levels of serum albumin,poor nutrition,and in the beginning phases of the sickness [32].Proteinlosing enteropathy is a possible reason for hypovitaminosis D in IBD [32];be that as it may,more point-by-point studies are expected to examine the mechanism of hypovitaminosis D in IBD.

Albeit the exact mechanism to make sense of the role of vitamin D in IBD has not been completely clarified,a few systems might be engaged in this process.In general,influencing chronic inflammation,intestinal mucosal barrier instability,and intestinal microbiota imbalance are how vitamin D may have a beneficial effect on improving IBD [29].First,vitamin D increases its bactericidal effect by activating its receptor in the cell,which conducts antibacterial function by modulating the expression of monocyte-induced antibacterial protein [33].On the other hand,this vitamin has been shown to stimulate a variety of cells to express nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 2(NOD2),which initiates nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB)through downstream signals,as a transcriptional activator [34].This transcription factor induces the expression of the gene encoding the antimicrobial peptide defensin beta 2 (DEFB2/HBD2) [34];second,vitamin D stimulates the production and differentiation of T helper cell type 2(Th2) cells through its direct effect on CD4+T cells and also by its effect on dendritic cells (DCs),and it modulates Th1 proliferation [35,36].Another function of this vitamin is to reduce the production of tumor necrosis factor-α(TNF-α),which inhibits mitogen-activated protein kinase(MAPK) and activates protein kinase phosphatase-1 [37],and third,regulation of integrity,enhancement of tight intercellular connections in intestinal epithelial cells,and finally strengthening of the intestinal mucosal barrier by vitamin D are stimulated by induction of the expression of strong junction proteins of occludin,zonula occludens 1 (ZO-1),and claudin-1,which could have a potential effect in improving IBD [38].In general,considering the potential deficiency of vitamin D in IBD,it seems that increasing and optimally maintaining the 25(OH) D3 level can have beneficial effects in these patients as a complementary treatment along with other common medical treatments.

In the analyzed examinations,vitamin D supplementation in individuals was safe (no critical aftereffects were noticed),and both high levels and standard levels of vitamin D were all around endured [39].Moreover,in all reviews performed with dosages of 2000–50,000 IU of vitamin D each week,no interaction was observed with conventional drugs and other common treatments used in IBD patients.In such a manner,and as per an efficient report,no serious side effects were seen at these dosages(except in rare cases of hypercalcemia and partial hyperphosphatemia) [24,29].

Owing to many bone problems and inflammatory disorders in IBD patients,especially in children,vitamin D supplementation can have beneficial effects on 25(OH) D3 level and other related markers,such as calcium levels and inflammatory markers involved in disease and bone resorption.Examining bone conditons can be very effective even in the treatment process and different types of treatment.On the other hand,reducing inflammation in these patients can be very helpful.Be that as it may,the impacts of vitamin D supplementation on illness seriousness-related measures in pediatric IBD are not yet clarified.

Our review has a few strengths.The current review is the first meta-analysis that researched the likely impacts of the vitamin D treatment on 25(OH) D3 level,PCDAI/PUCAI score,inflammatory variables,calcium,and PTH in kids and teenagers with IBD.In this meta-analysis,we attempted to incorporate all potential studies in light of the critera so the high volume of studies could expand the exactness of the outcomes.What’s more,we played out a subgroup examination to explore the origins of heterogeneity to concentrate on results with high heterogeneity.The subgroups depended on the dosages of supplementation and on the span of follow-up.

Limitations of the current review were the inclusion of studies without having a proper benchmark group,different critera for patients included for this review,information inaccessibility of other normal medicines and history of past ailments,different levels of PCDAI/PUCAI score,and eventually unique fundamental characteristics (such as age,sex,weight record,and term of IBD illness) which favors heterogeneity of populaces and at last influence the outcomes.Moreover,the absence of adequate investigations to perform subgroup examination in light of the principal IBD subgroups was one more impediment to this meta-analysis.

In conclusion,the consequences of the current review demonstrated that vitamin D treatment can affect levels of 25(OH) D3,calcium,and provocative variables.Nonetheless,further exploration is as yet expected to affirm these discoveries.

Supplementary InformationThe online version contains supplementary material available at https:// doi.org/ 10.1007/ s12519-022-00605-6.

Author contributionsRP,SMH: conception,design,statistical analysis,data collection,writing–original draft,supervision.MF,AH,ME,FF: data collection and writing–original draft.All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

FundingThis research was supported by grant No.1401-1-249-57731 from the Tehran University of Medical Sciences.The funding body had no role in designing the study and did not take part in data collection,data analysis,interpretation of the data,or writing of the manuscript.

Data availabilityData are available on request due to privacy/ethical restrictions.

Declarations

Ethical approvalThe study protocol was ethically approved by the Regional Bioethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (No: IR.TUMS.CHMC.REC.1401.060).

Conflict of interestNo financial or non-financial benefits have been received or will be received from any party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

World Journal of Pediatrics2023年1期

World Journal of Pediatrics2023年1期

- World Journal of Pediatrics的其它文章

- Innovative treatments for congenital heart defects

- Perioperative extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in pediatric congenital heart disease: Chinese expert consensus

- Role of ultrasound in the treatment of pediatric infectious diseases:case series and narrative review

- Manual and alternative therapies as non-pharmacological interventions for pain and stress control in newborns: a systematic review

- Assessment of compatibility of rhIGF-1/rhIGFBP-3 with neonatal intravenous medications

- Development of necrotizing enterocolitis after blood transfusion in very premature neonates