Sm-Nd同位素体系在月球早期演化中的研究进展

徐玉明, 王桂琴, 杨 振, 曾玉玲

Sm-Nd同位素体系在月球早期演化中的研究进展

徐玉明1, 2, 王桂琴1, 3*, 杨 振1, 2, 曾玉玲1, 2

(1. 中国科学院 广州地球化学研究所, 同位素地球化学国家重点实验室, 广东 广州 510640; 2. 中国科学院大学, 北京 100049; 3. 中国科学院 比较行星学卓越创新中心, 安徽 合肥 230026)

月球的形成时间和演化历史对太阳系类地行星的演化有重要意义。Sm-Nd同位素体系因其独特的元素和同位素地球化学性质, 为月球早期岩浆洋的结晶分异过程提供了强有力的制约。本文综述了147Sm-143Nd和146Sm-142Nd同位素体系的应用原理, 以及目前对月球亚铁斜长岩、镁质岩套、碱质岩套、克里普岩和月海玄武岩Sm-Nd同位素体系的相关研究。最新的研究结果表明, 全月球(或近乎全月球)范围在约4.35 Ga经历了Sm-Nd同位素体系的平衡, 但对这一平衡事件的解释仍存在争议,主要有3种观点: ①原始月球岩浆洋在4.35 Ga形成并快速结晶分异; ②月球经历了较长时间的冷凝结晶, 4.35 Ga为这一过程的结束时间; ③月球在4.35 Ga发生某种全球性事件, 造成Sm-Nd同位素体系平衡重置。另外, 通过月球样品测得的固体硅酸盐月球(BSM)的142Nd值变化范围较大(−0.19 ~ −0.01), 因此, 月球的初始组成为球粒陨石组成(142Nd=−0.19)的传统观点也有待进一步证实。目前为止, 月球的形成和演化过程仍不明晰, 而Sm-Nd同位素体系是月球形成和演化过程研究最重要的工具之一。

月球; Sm-Nd同位素体系; 演化过程; 年代学

0 引 言

月球作为地球唯一的卫星, 是研究太阳系类地行星热演化和化学演化的重要窗口。目前, 有关月球形成的模型很多, 如分裂说(Ringwood, 1960)、共增生说(Ruskol, 1972)、俘获说(Urey, 1966)和大碰撞学说(Hartmann and Davis, 1975; Shearer et al., 2006)。其中, “大碰撞”学说是目前普遍接受的假说。这一假说认为月球形成于约4.5 Ga前, 一个火星大小的撞击体(Thiea)与原地球之间发生低角度偏心碰撞。碰撞造成了原始地球的自转轴偏移, 飞溅出来的硅酸盐物质最终吸积形成原始月球, 并产生了岩浆洋。目前的研究认为, 月球岩浆洋冷凝过程中首先结晶出橄榄石和辉石, 并下沉形成堆积月幔。当岩浆洋凝固达到75%时, 富Al和Ca的残余熔体开始结晶形成斜长石, 并上浮形成原始长石质月壳。岩浆洋凝固达到95%时, 残余熔体逐渐富集Ti和Fe, 形成密度较大的含钛铁矿堆积层。结晶的最后阶段, 形成K、REEs和P等不相容元素极为富集的克里普岩(KREEP 岩)(Wood et al., 1970; Elkins-Tanton et al., 2011; Pernet-Fisher and Joy, 2016; Schaefer and Elkins-Tanton, 2018)。这类岩石含有较高含量的放射性元素Th和U, 它们的衰变可能产生足够的热量, 使已固结的月幔重熔生成新的熔体。这些组成不同、更加年轻的熔体侵入斜长质月壳形成次生月壳岩石, 如镁质岩套和碱质岩套(Pernet-Fisher and Joy, 2016)。通过同位素地质年代学的手段, 测定这些原始堆积岩和次生岩石源区的形成年龄, 就可以限定岩浆洋的冷凝时间和演化历史。

Sm和Nd均为轻稀土元素, 具有难熔、亲石和不相容性等特征(Carlson, 2015)。因此, 行星形成演化过程中Sm和Nd主要进入硅酸盐相, 在星云凝结或蒸发过程几乎不会发生Sm/Nd值的改变(Boyet and Carlson, 2005), 并且在部分熔融或结晶分异过程中更易进入熔体相, 而Nd比Sm更不相容, 导致月壳岩石比月幔岩石的Sm/Nd值更低。Sm和Nd的这些特殊性质, 结合147Sm-143Nd和146Sm-142Nd放射性衰变体系, 使其成为研究月球形成和演化的重要工具。另外, 与Rb-Sr、U-Pb和Ar-Ar同位素体系相比, Sm-Nd同位素体系更稳定, 在风化和热变质作用中具有更强的抗扰动性(Borg et al., 2015), 应用于月球壳幔演化、示踪岩浆物质来源等研究中更具优势。本文通过已报道的相关研究, 总结了Sm-Nd同位素体系在月球早期演化研究中的应用原理、研究进展和存在问题。

1 Sm-Nd同位素定年原理

自然界中, Sm和Nd均有7种同位素, 同位素组成和丰度见表1。其中,147Sm、148Sm和149Sm为长寿命放射性同位素, 而148Sm和149Sm的半衰期太长(约107Ga), 在现有技术条件下无法测量出其子体同位素的变化, 故目前不能成为定年工具。147Sm通过α衰变为子体143Nd, 半衰期(147 1/2)为106 Ga (Lugmair and Marti, 1978);146Sm通过α衰变为子体142Nd, 半衰期(146 1/2)为68 Ma(Kinoshita et al., 2012)或103 Ma(Friedman et al., 1966; Meissner et al., 1987) (有争议, 详见3.3节)。146Sm半衰期较短, 在太阳系形成约500 Ma后就几乎完全衰变(Rankenburg et al., 2006), 被称为灭绝核素。

1.1 147Sm-143Nd体系定年原理

1.1.1 等时线年龄

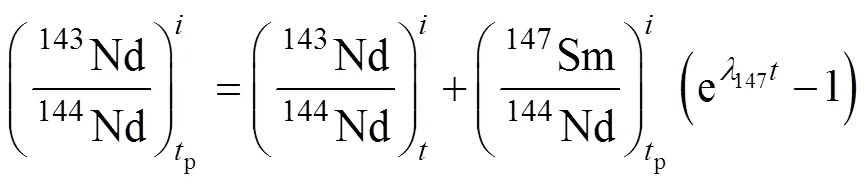

封闭体系中母体147Sm衰变为子体143Nd的时间函数为:

表1 Sm和Nd同位素组成(Carlson, 2015)

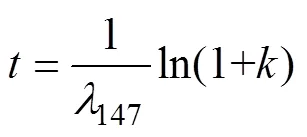

式中:147Sm的衰变常数147=0.00654 Ga−1(Reiners et al., 2017);表示不同的封闭体系或样品; (143Nd/144Nd)p和(147Sm/144Nd)p为样品当前的实际测量值; (143Nd/144Nd)为样品形成时(时刻)的初始值。因此, 对同源样品的(143Nd/144Nd)p和(147Sm/144Nd)p测定值进行投图, 就可以获得一条线性相关的等时线, 若等时线斜率为, 则样品的形成时间为:

1.1.2 模式年龄

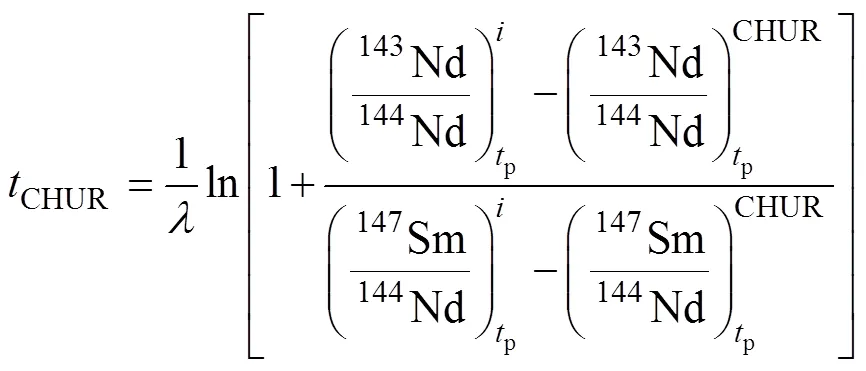

Sm-Nd模式年龄最初由DePaolo and Wasserburg (1976)提出。假设月球和地球一样, 初始组成与球粒陨石(chondritic uniform reservoir, CHUR)一致, 那么将样品的143Nd/144Nd和147Sm/144Nd测定值与CHUR相比, 就可以计算出样品的模式年龄(CHUR):

式中: (143Nd/144Nd)CHURp和(147Sm/144Nd)CHURp为CHUR的值, 分别为0.512638(Hamilton et al., 1983)和0.1967 (Jacobsen and Wasserburg, 1980)。此公式适用于单阶段模式年龄, 即样品来自与CHUR组成一致的封闭体系, Sm/Nd值保持不变。

1.2 146Sm-142Nd体系定年原理

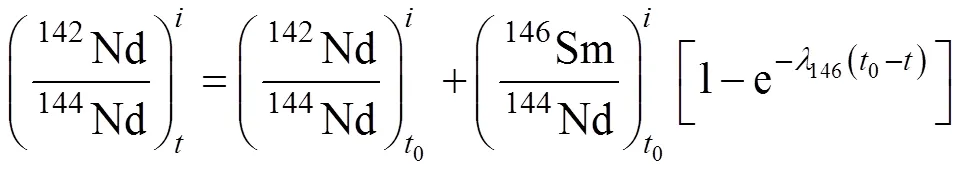

作为短寿命灭绝核素,146Sm-142Nd体系可为太阳系早期约500 Ma以内的演化事件提供精确的时间限制。142Nd随时间变化的函数为:

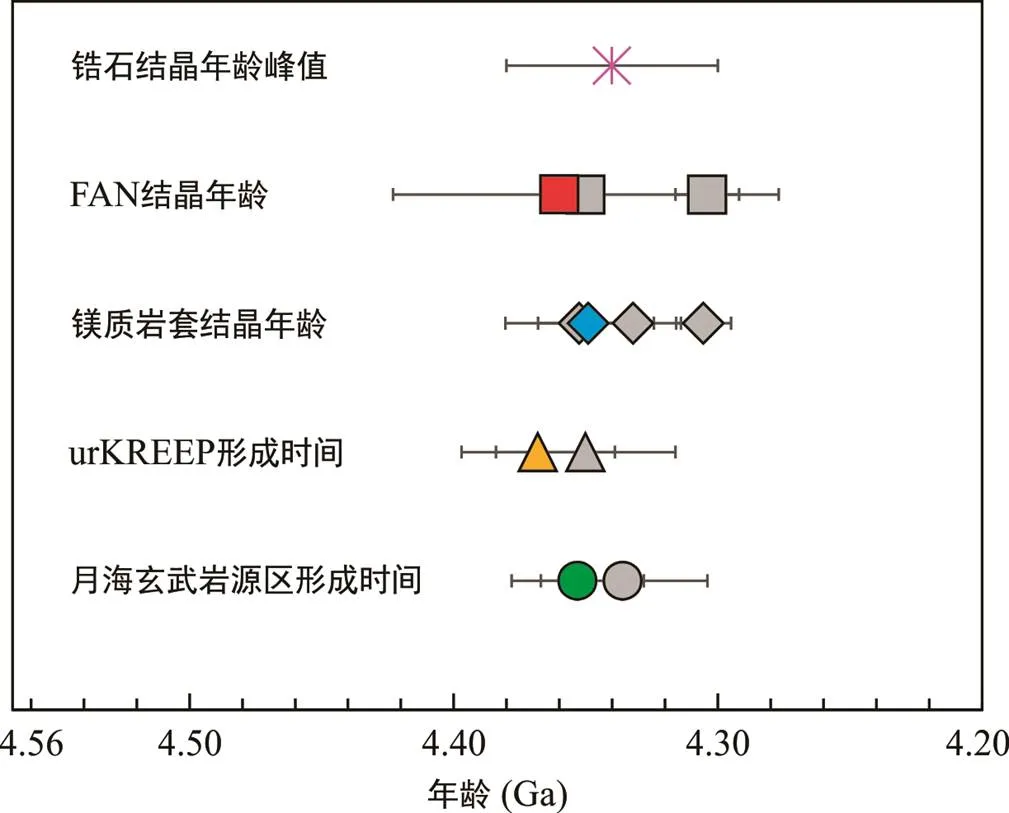

由于太阳系形成时的(146Sm/144Nd)0值无法直接测量, 因此将其转化为易测量的参数:

式中,0=4.567 Ga, 为太阳系形成的时间(Amelin et al., 2010);146=6.7296 Ga−1(Marks et al., 2014); (146Sm/144Sm)0= 0.00828(Marks et al., 2014); (144Sm/147Sm)Stdp=0.202419 (Borg et al., 2016), 由AMES Sm同位素标准物质获得。目前, 通过月球样品的146Sm-142Nd体系限定月球岩浆洋冷凝时间的方法主要有2种, 但无论哪种方法都需要首先获得这些样品源区的147Sm/144Nd值。

1.2.1 源区的147Sm/144Nd值

计算源区的147Sm/144Nd值是146Sm-142Nd体系定年的前提。由于大部分月球样品经历了多阶段的演化, 样品的147Sm/144Nd测量值并不能代表源区的147Sm/144Nd值。因此, 需要假设可能形成这些月球岩石的演化模型(Rankenburg et al., 2006; Boyet and Carlson, 2007; Brandon et al., 2009; McLeod et al., 2014), 来计算源区的147Sm/144Nd值。以典型的CHUR组成模型为例,143Nd(样品的143Nd/144Nd值相对球粒陨石均一库的万分偏差)经历了3个阶段的变化(图1a): 第1阶段为假设具有CHUR组成的固体硅酸盐月球(bulk silicate Moon, BSM)的演化, 直到1时刻BSM分异形成大规模的富集储库(enriched reservoirs, ER)和亏损储库(depleted reservoirs, DR); 第2阶段为ER和DR的独立演化, 直到2时刻, 这些储库发生部分熔融, 冷凝形成月海玄武岩(Lunar mare basalts, LMB); 第3阶段为LMB中的Nd同位素封闭演化至今。因此, 月海玄武岩源区的形成时间就代表了BSM分异的时间。而对于146Sm-142Nd体系,142Nd(样品的142Nd/144Nd值相对地球Nd同位素标准物质的万分偏差)随时间的变化实际上只有2个阶段(图1b), 因为146Sm在第3阶段开始时就已经灭绝。

根据图1a, 源区的(147Sm/144Nd)Sp可以表示为:

1.2.2142Nd/144Nd-147Sm/144Nd等时线年龄

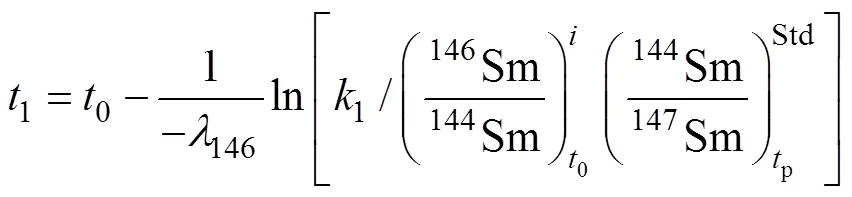

142Nd/144Nd-147Sm/144Nd行星等时线年龄与常规全岩等时线定年类似, 对岩浆洋冷凝形成的原生样品, 如月壳、月幔和urKREEP等进行测定, 就可获得其等时线年龄。但由于无法直接获得这些样品, 实际样品通常使用其衍生的岩石样品(如斜长岩、月海玄武岩和KREEP岩等)(Nyquist et al., 1995; Rankenburg et al., 2006; Boyet and Carlson, 2007; Brandon et al., 2009; Borg et al., 2019)。前提条件是这些样品具有与月球岩浆洋相同的初始同位素组成。因此,根据式(6) 计算的源区比值(147Sm/144Nd)Sp和样品的142Nd/144Nd测定值, 可以绘制出月海玄武岩源区的146Sm-142Nd等时线(图2a)。若等时线斜率为1, 则源区的形成时间1为:

因为式(6)的计算需要源区的形成时间1已知, 所以式(6)和(7)必须通过迭代计算解出。

1.2.3142Nd/144Nd-143Nd/144Nd等时线年龄

另一种计算月海玄武岩源区形成年龄的方法是通过源区现今的142Nd/144Nd-143Nd/144Nd或142Nd-143Nd等时线图获得(Brandon et al., 2009; McLeod et al., 2014)。由于月海玄武岩一般形成于146Sm灭绝之后, 源区当前的(142Nd/144Nd)Sp应等于月海玄武岩中的142Nd/144Nd测量值。而源区当前的(143Nd/144Nd)Sp需通过样品形成时的初始143Nd/144Nd和源区的(147Sm/144Nd)Sp计算获得。因此, 在142Nd-143Nd图解(图2b)中, 源区形成的模式年龄可以通过等时线的斜率2解出:

式中:(142Nd/144Nd)Stdp=1.141832(Rankenburg et al., 2006); (143Nd/144Nd)CHURp= 0.512638(Hamilton et al., 1983)。另外, 由于等式两侧都存在1, 因此这一方程也需要迭代解出。

BSM. 固体硅酸盐月球; DR. 亏损储库; ER. 富集储库; LMB. 月海玄武岩; FAN. 亚铁斜长岩。

图1 ε143Nd(a)和ε142Nd(b)的多阶段演化示意图

Fig.1 Schematic plots of multi-stage differentiation of ε143Nd (a) and ε142Nd (b)

图2 142Nd/144Nd-147Sm/144Nd等时线图(a, 据Rankenburg et al., 2006)和ε142Nd-ε143Nd等时线图(b, 据Brandon et al., 2009)

2 月球的Sm-Nd同位素年龄

月壳、urKREEP和月幔(月海玄武岩源区)为岩浆洋冷凝的原生产物, 是整个硅酸盐月球的重要组成部分, 其形成时间能够为岩浆洋的凝固时间和月球的形成时间提供强有力的约束。

2.1 月壳的形成时间

高地月壳的岩石包括亚铁斜长岩(ferroan anorthosite, FAN)、镁质岩套(Mg-suite)和碱质岩套(alkali-suite) (Lucey, 2006; Wieczorek, 2006)。表2汇总了以Sm-Nd同位素体系开展的有关月壳岩石样品形成时间的相关研究结果。目前的观点认为, FAN是岩浆洋冷凝的直接产物, 为月球上最古老的岩石, 代表了原始月壳的组成, 其结晶年龄是限定月壳形成年龄的直接依据(Sio et al., 2020)。然而, 关于准确的FAN形成年龄仍存在争议。一方面, 最古老和最年轻的FAN形成年龄分别为4562±68 Ma(Alibert et al., 1994)和4290±60 Ma(Borg et al., 1999), 年龄差异高达约272 Ma,而根据热演化模型, 岩浆洋的冷凝时间为10~200 Ma (Elkins-Tanton et al., 2011; Maurice et al., 2020)。另一方面, 一些研究表明FAN的初始143Nd>0(Borg et al., 1999; Norman et al., 2003; Nyquist et al., 2010; Boyet et al., 2015), 与其岩浆洋起源的观点并不一致。根据Sm和Nd的元素地球化学性质, 在岩浆洋结晶过程中, 形成FAN的熔体应具有更低的Sm/Nd值, 即FAN的初始143Nd应小于或接近0。镁质岩套是侵入古老斜长质月壳的物质, 并在与月壳混染作用中获得了较多的不相容微量元素(Shearer et al., 2015), 代表了岩浆洋冷凝的时间下限, 其形成年龄应不早于FAN的形成时间。但已报道的镁质岩套结晶年龄范围为4528~4161 Ma(表2; Compston et al., 1975; Papanastassiou and Wasserburg, 1975), 与FAN的形成年龄范围有很大的重合。碱质岩套的成因与镁质岩套形成有关, 均被认为是由KREEP岩浆结晶分异而成(Snyder et al., 1995; Wieczorek et al., 2006), 尽管样品数量少, 但也为理解月壳后期的演化提供了重要信息。然而, 目前关于碱质岩套的Sm-Nd年代学数据很少。FAN较大的年龄差异以及与镁质岩套重叠的年龄, 增加了月壳形成演化的复杂性, 意味着传统岩浆洋演化模型可能需要进行修正。

表2 月壳岩石样品年龄

续表2:

2.2 urKREEP的形成时间

urKREEP指岩浆洋分离结晶最后阶段的残余熔体(Warren and Wasson, 1979), 在与月壳或月幔混染过程中形成KREEP岩, 被认为是所有KREEP岩的源区。因此, urKREEP的形成年龄可能代表了岩浆洋分异完成的时间。早期的研究中, 使用Sm-Nd和Rb-Sr同位素体系计算了源区urKREEP的模式年龄分别为4360±60 Ma(Carlson and Lugmair, 1979)和4420±70 Ma(Nyquist and Shih, 1992)。近年来, 通过富KREEP样品的结晶年龄和初始同位素组成相结合的方式计算urKREEP的模式年龄(Edmunson et al., 2009; Sprung et al., 2013), 但所获年龄存在差异, 如Edmunson et al. (2009)获得urKREEP的Sm-Nd模式年龄为4492±61 Ma, 略高于Lu-Hf模式年龄(4402±23 Ma; Sprung et al., 2013)。之后, Gaffney and Borg (2014b)同时测量并计算了urKREEP的Lu-Hf和Sm-Nd模式年龄, 获得了相似的年龄分别为4353±37 Ma和4389±45 Ma, 加权平均值为4368±29 Ma,表明 Lu-Hf和Sm-Nd同位素体系记录了相同的地质事件, 可能代表了urKREEP的形成时间。此结果与Borg et al. (2020)最新获得urKREEP 的Sm-Nd模式年龄(4350±34 Ma)一致, 表明月球岩浆洋冷凝过程可能在太阳系形成后约200 Ma完成。

2.3 月海玄武岩源区的形成时间

月海玄武岩是月球岩浆洋结晶完成之后月幔部分熔融的产物。因此, 月海玄武岩源区的形成时间代表了月幔的形成时间。采用146Sm-142Nd和147Sm-143Nd同位素体系可计算月海玄武岩源区(月幔)的模式年龄。据此, Nyquist et al. (1995)最先以月幔3阶段演化模型计算的模式年龄为4329+40 −56 Ma,142Nd为−0.01±0.03。Rankenburg et al. (2006)通过月海玄武岩和KREEP的142Nd/144Nd-147Sm/144Nd等时线, 得到了相似的月幔形成年龄为4352+21 −23Ma, 但142Nd不同, 为−0.19±0.02。此后相继开展的一些研究也都证实月海玄武岩源区的形成年龄集中分布于4.30~4.40 Ga(Boyet and Carlson, 2007; Brandon et al., 2009; Gaffney and Borg, 2014a; McLeod et al., 2014; Borg et al., 2019), 加权平均值为4349±9 Ma, 与urKREEP的模式年龄(4350±34 Ma)一致, 表明urKREEP和月海玄武岩源区可能几乎同时形成。

3 Sm-Nd同位素体系在月球研究中的几个关键问题

3.1 月球样品Sm-Nd年龄的含义

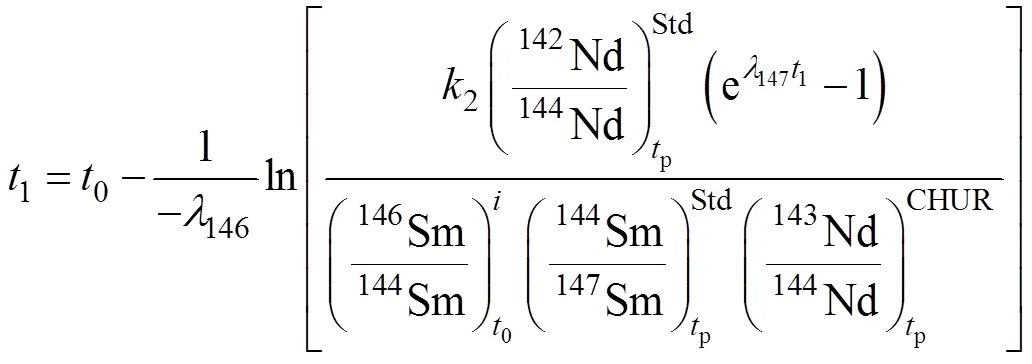

如前所述, 月海玄武岩源区和urKREEP的年龄变化较小, 而高地月壳岩石样品的年龄差异较大, 甚至同一块样品给出不同的形成时间(Carlson and Lugmair, 1988; Borg et al., 2011)。因此, 如何评价这些已报道年龄的可靠性是问题的关键。Borg et al. (2015)提出可靠的年代学数据应满足以下条件: ①获得多种同位素体系的一致年龄; ②等时线的线性程度(mean square weighted deviation, MSWD)小于5; ③采用抗扰动性强的Sm-Nd体系; ④初始同位素的组成与样品的岩石成因一致; ⑤各矿物相中母子体元素的丰度合理。根据这些条件, Borg et al. (2015)认为 FAN最可靠的年龄为4360±3 Ma, 镁质岩套最可靠的年龄为4349±19 Ma, 锆石峰值年龄为代表的碱质岩套年龄为4340±40 Ma, urKREEP的最新模式年龄为4368±29 Ma, 月海玄武岩源区的加权平均年龄为4349±9 Ma(图3彩色数据)。而在Borg et al. (2015)之后, 最新的一些研究也证实各类月球岩石源区可能具有相似的形成时间(图3灰色数据; Borg et al., 2017, 2019, 2020; Marks et al., 2019; Sio et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021), 表明约4.35 Ga前月球经历了大范围甚至全球范围的岩浆事件。这一岩浆事件是否与原始岩浆洋的冷凝有关是目前争论的焦点, 主要的观点有3种: ①月球形成时间较晚, 反映了原始月球岩浆洋在4.35 Ga 形成并快速冷凝和分异的时间(Nyquist et al., 1995; Gaffney and Borg, 2014b; Borg et al., 2019); ②月球形成于约4.567 Ga, 由于放射性产热(Shearer et al., 2006)和潮汐加热(Meyer et al., 2010; Chen and Nimmo, 2016)等其他热源的存在, 延长或推迟了岩浆洋冷凝的时间, 4.35 Ga为月球岩浆洋冷凝完成的时间; ③月球形成于约4.567 Ga, 4.35 Ga的年龄可能代表了原始岩浆洋快速凝固之后的Sm-Nd同位素体系平衡重置的时间, 如碰撞改造作用(Carlson et al., 2014; Gross et al., 2014; McLeod et al., 2014; Marks et al., 2019)或月幔翻转作用(Borg et al., 2020; Sio et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2020)等。最新的研究(Borg et al., 2020; Sio et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2020)认为月幔翻转过程可能是解释这一年轻年龄更合理的原因。这种观点认为岩浆洋冷凝的最后阶段, 超基性月幔和上覆含钛铁矿的堆积岩层在密度差异的作用下会发生对流翻转(Hess and Parmentier, 1995), 此时, 上涌的超基性堆积岩减压熔融并同化混染了FAN和富KREEP的岩石形成了镁质岩套和碱质岩套的母岩浆。相关的动力学模拟实验表明(Li et al., 2019; Morison et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2022), 月幔翻转可能在岩浆洋冷凝之后, 甚至同时发生。

3.2 月球的142Nd/144Nd初始值

142Nd/144Nd-147Sm/144Nd月球等时线的截距代表了BSM的142Nd/144Nd初始值。然而, 目前已报道BSM的142Nd值却并不一致, 介于地球(142Nd=0; Nyquist et al., 1995; Boyet and Carlson, 2007)与CHUR平均值(142Nd=−0.19±0.04)之间。CHUR的142Nd值为碳质球粒陨石(−0.35±0.15)、普通球粒陨石(−0.19±0.05)和顽辉球粒陨石(−0.10±0.12)ε142Nd值的加权平均值(Rankenburg et al., 2006; Gannoun et al., 2011; McLeod et al., 2014; Borg et al., 2019)。这意味着月球的142Nd值和Sm/Nd值或者与地球一致, 即相对CHUR更高(超球粒陨石模型, super chondritic model, SCHM); 或者与CHUR一致, 相对地球更低(球粒陨石模型)。为了评价BSM的组成, Brandon et al. (2009)和McLeod et al. (2014)讨论了2种月球演化模型的可能性, 结果证明月球与地球的ε142Nd值和Sm/Nd值都比CHUR高。Sprung et al. (2013)采用147Sm-143Nd和176Lu-176Hf同位素体系进一步验证了SCHM的可能性。如图4, 在Nd-Hf图解中, 低Ti玄武岩源区和KREEP岩源区的Nd和Hf具有明显的相关性, 且几乎经过了CHUR的值(原点)却未经过SCHM的值。并且Hf相同时, 低Ti玄武岩的放射成因143Nd值明显低于SCHM的值, 证明月球应具有CHUR的Sm/Nd值, 与此相对应的142Nd值为−0.07±0.02, 接近顽辉球粒陨石的值(−0.10±0.12), 而与CHUR平均值(−0.19±0.04)存在差异。如果月球与CHUR具有相同的Sm/Nd值, 那么月球与不同类型CHUR之间的142Nd/144Nd差异则可能为核合成异常所致。最近, Borg et al. (2019)获得了月球的142Nd值为−0.15±0.05, 十分接近普通CHUR(−0.19±0.05)而不同于地球, 认为地月间的142Nd差异与地球和月球来自不同Sm/Nd值的储库有关, 一种可能的情形是月球在大碰撞过程中继承了原地球Sm/Nd较低的部分。由于缺乏直接可靠的证据, 目前月球的142Nd/144Nd组成仍需要进一步厘定。

彩色数据引自Borg et al., 2015; 灰色数据引自Borg et al., 2017, 2019, 2020; Marks et al., 2019; Sio et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021。

3.3 146Sm半衰期: 68 Ma vs. 103 Ma

146Sm半衰期的大小不仅影响着太阳系初始(146Sm/144Sm)0的大小, 还与行星早期演化时序的建立紧密相关。1953–2014年,146Sm的半衰期先后被测量过6次, 分别为50 Ma(Dunlavey and Seaborg, 1953)、74±15 Ma(Nurmia et al., 1964)、102.6±4.8 Ma (Friedman et al., 1966)、103.1±4.5 Ma(Meissner et al., 1987)、68±7 Ma(Kinoshita et al., 2012)和69 Ma(Qian and Ren, 2014)。前5次的146Sm半衰期数据是由粒子计数实验测得, 最后1次的数据是通过密度相关的聚类模型(density-dependent cluster model)计算获得。然而, 无论是实验测量还是模拟计算, 都不可避免地存在着人为因素产生的系统误差, 如人工合成含146Sm溶液的纯度、化学计量数、精确的同位素组成以及146Nd对146Sm的同质异位素干扰等, 导致所报道146Sm半衰期的差异高达30%。尽管实验测得的146Sm半衰期存在差异, 但在宇宙化学研究领域普遍采用103 Ma这一半衰期值(Friedman et al., 1966; Meissner et al., 1987)。Kinoshita et al. (2012)首次采用Ln树脂和加速器质谱法(AMS), 消除了146Nd对146Sm的同质异位素干扰, 测得了精度相对更高的146Sm半衰期值为68±7 Ma。这不仅意味着太阳系形成时的(146Sm/144Sm)0初始值(0.0094±0.0005; Kinoshita et al., 2012)相对早期的估计值(0.0085±0.0007; Boyet et al., 2010)或许更高, 还意味着早期采用103 Ma建立的行星演化时序都需进行修正。然而, Marks et al. (2014)通过富钙铝包体(CAI)中矿物分离相的146Sm-142Nd内部等时线直接获得的(146Sm/144Sm)0初始值为0.00828±0.00044, 表明Kinoshita et al. (2012)报道的半衰期可能并不准确。此外, 通过对比月球样品和其他陨石样品的Pb-Pb、147Sm-143Nd与146Sm-142Nd年龄也发现, 采用(146Sm/144Sm)0为0.00828、半衰期为103 Ma所计算出的146Sm-142Nd年龄与相同样品的Pb-Pb、147Sm-143Nd年龄更加一致(Marks et al., 2014)。这些结果表明146Sm 的半衰期真值可能仍是103 Ma。然而, “同位素地球科学”联合工作组(IUPAC-IUGS)从实验技术的角度认为目前所报道的实验都没有详尽讨论各种可能的人工误差和模型内在的系统偏差, 因此很难评价146Sm半衰期的合理性, 建议在应用146Sm-142Nd体系研究太阳系的早期演化问题时, 最好同时考虑这2种不同的半衰期值, 并计算出2种相对应的年龄(Villa et al., 2020)。

SCHM. 超球粒陨石模型; CHUR. 球粒陨石模型。修改自Sprung et al., 2013; Dickin, 2018。

3.4 中子捕获效应校正

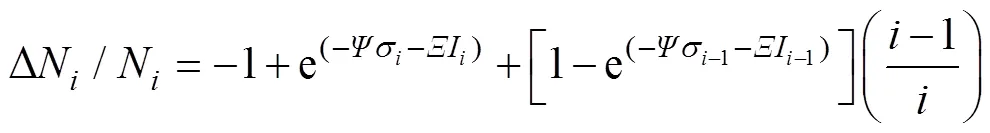

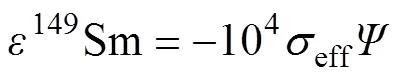

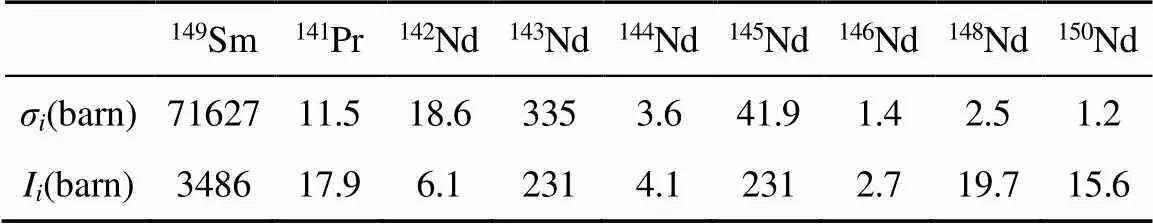

月球表面的物质在银河系宇宙射线的作用下会产生大量的中子, 受中子辐射的影响, 月表岩石的Sm和Nd同位素组成会发生漂移, 相关研究(Nyquist et al., 1995)显示, 遭受中子辐射最严重的低Ti玄武岩(12309)样品的149Sm异常可达−43.2, 与此同时, 对142Nd测量值的校正量高达3.2×10−5。Nyquist et al. (1995)定义了中子辐射影响下Nd同位素漂移(ΔN/N) 的公式:

式中:为中子俘获反应生成的子核,=142Nd、143Nd、144Nd、145Nd、146Nd、148Nd和150Nd; (−1)为中子俘获反应的靶核; (−1)/为2种核素丰度的初始比值;σ和I分别为热中子俘获截面和超热中子共振积分截面(cm2);和分别为热中子通量和超热中子通量(n/cm2)。Rankenburg et al. (2006)计算的Nd同位素以及149Sm和141Pr的σ和I见表3。

因此, 只要获得2种中子通量和的值, 就可以计算Nd同位素因中子俘获而产生的变化量。149Sm由于具有较大的热中子俘获截面, 常被用来计算的大小:

式中:149Sm表示149Sm/152Sm相对地球标准物质的万份偏差;eff为149Sm的有效热中子俘获截面。若/值已知, 则可计算出值, 但/值却难以估算。目前已报道的/值并不相同, 变化范围较大, 为0.31~3.03(Nyquist et al., 1995; Rankenburg et al., 2006; Sprung et al., 2013)。并且这些/值都是通过Apollo返回样品所获得, 该区域的中子辐射情况是否与其他地区相同仍需要验证。Gaffney and Borg (2014b)根据Hf和Sm同位素建立了一种模拟计算和的方法。假设辐射前样品的Hf和Sm同位素组成与JMC 745 Hf和AMES Sm同位素标准一致, 然后在给定和的前提下模拟计算辐射后的Hf和Sm同位素比值, 之后再通过卡方检验(chi-squared misfit)对比模拟值与样品测量值的接近程度。这种方法解决了/值难以估算的问题, 更加简单方便且适用范围更广, 既适用于月球返回样品, 也适用于月球陨石样品。

表3 热中子俘获截面和超热中子共振积分截面(Rankenburg et al., 2006)

注: 1 barn=10−24cm2。

4 主要认识和研究展望

147Sm-143Nd和146Sm-142Nd同位素体系由于其独特的地球化学性质, 在研究月球早期岩浆演化中发挥了重要作用并得到了很好的应用。通过总结147Sm-143Nd和146Sm-142Nd同位素体系在月球早期演化中的研究结果, 目前已获得了以下一些重要的认识:

(1) 最近的研究结果表明, 月海玄武岩源区、urKREEP、FAN、镁质岩套以及碱质岩套可能具有年轻且一致的形成年龄, 约4.35 Ga, 意味着月球在约4.35 Ga前存在大范围甚至全月球范围的岩浆事件, 但这一岩浆事件所代表的动力学过程仍需要进一步的探究。

(2) 传统观点认为, 月球应具有与CHUR一致的142Nd值。然而, 通过月球样品研究获得的142Nd值变化范围较大, 为−0.19 ~ −0.01。因此, 月球可能具有更加复杂的组成和演化模型。

(3)146Sm半衰期仍有争议, 分别为103 Ma和68 Ma。在此半衰期尚未确定的情况下, 月球样品研究中应同时考虑2个值的计算结果。

(4) 中子俘获对Sm-Nd同位素定年结果的影响较大。目前, 利用Hf和Sm同位素模拟和的大小并校正中子俘获的影响可能是更加合理的方法, 因为这种方法的应用范围更广, 既适用于月球返回样品, 也适用于月球陨石样品。

目前对月球Sm-Nd同位素体系的研究主要是基于Apollo返回样品的研究, 尽管已获得了很多数据和认识, 但这些样品的采样点具有很大的局限性, 样品是否能够代表整个月球仍是一个重要问题。我国正在和即将开展的一系列登月探测和采样任务, 将为这一研究提供更全面的研究样品, 也将为月球的起源演化提供更详实的科学证据。

致谢:感谢两位审稿专家对本文提出的建设性修改意见。

Amelin Y, Kaltenbach A, Iizuka T, Stirling C H, Ireland T R, Petaev M, Jacobsen S B. 2010. U-Pb chronology of the Solar System’s oldest solids with variable238U/235U., 300(3–4): 343–350.

Borg L, Norman M, Nyquist L, Bogard D, Snyder G, Taylor L, Lindstrom M. 1999. Isotopic studies of ferroan anorthosite 62236: A young Lunar crustal rock from a light rare-earth-element-depleted source., 63(17): 2679–2691.

Borg L E, Brennecka G A, Symes S J K. 2016. Accretion timescale and impact history of Mars deduced from the isotopic systematics of martian meteorites., 175: 150–167.

Borg L E, Cassata W S, Wimpenny J, Gaffney A M, Shearer C K. 2020. The formation and evolution of the Moon’s crust inferred from the Sm-Nd isotopic systematics of highlands rocks., 290: 312–332.

Borg L E, Connelly J N, Boyet M, Carlson R W. 2011. Chronological evidence that the Moon is either young or did not have a global magma ocean., 477: 70–72.

Borg L E, Connelly J N, Cassata W S, Gaffney A M, Bizzarro M. 2017. Chronologic implications for slow cooling of troctolite 76535 and temporal relationships between the Mg-suite and the ferroan anorthosite suite., 201: 377–391.

Borg L E, Gaffney A M, Kruijer T S, Marks N A, Sio C K, Wimpenny J. 2019. Isotopic evidence for a young Lunar magma ocean., 523, 115706.

Borg L E, Gaffney A M, Shearer C K. 2015. A review of Lunar chronology revealing a preponderance of 4.34– 4.37 Ga ages., 50(4): 715–732.

Boyet M, Carlson R W. 2005.142Nd evidence for early (>4.53 Ga) global differentiation of the silicate Earth., 309(5734): 576–581.

二是加强信息化建设。利用3S、网络技术加快北京市水土保持核心业务管理系统建设,以小流域为单元,实现市、区两级预防监督、监测等业务网络化管理,实现水土保持建设和管理从定性到定量、从平面到空间、从静态到动态、从粗放到精细的转变,提高了水土保持的精细化管理水平。

Boyet M, Carlson R W. 2007. A highly depleted Moon or a non-magma ocean origin for the Lunar crust?, 262: 505–516.

Boyet M, Carlson R W, Borg L E, Horan M. 2015. Sm-Nd systematics of Lunar ferroan anorthositic suite rocks: Constraints on Lunar crust formation., 148: 203–218.

Boyet M, Carlson R W, Horan M. 2010. Old Sm-Nd ages for cumulate eucrites and redetermination of the solar system initial146Sm/144Sm ratio., 291(1–4): 172–181.

Brandon A D, Lapen T J, Debaille V, Beard B L, Rankenburg K, Neal C. 2009. Re-evaluating142Nd/144Nd in Lunar mare basalts with implications for the early evolution and bulk Sm/Nd of the Moon., 73: 6421–6445.

Carlson R W. 2015. Sm-Nd dating // Rink J W, Thompson J. Encyclopedia of Scientific Dating Methods. Dordrecht: Springer: 768–780.

Carlson R W, Borg L E, Gaffney A M, Boyet M. 2014. Rb-Sr, Sm-Nd and Lu-Hf isotope systematics of the Lunar Mg-suite: The age of the Lunar crust and its relation to the time of Moon formation., 372(2024), 20130246.

Carlson R W, Lugmair G W. 1979. Sm constraints on early Lunar differentiation and the evolution of KREEP., 45: 123–132.

Carlson R W, Lugmair G W. 1981a. Sm-Nd age of lherzolite 67667: Implications for the processes involved in Lunar crustal formation., 56: 1–8.

Carlson R W, Lugmair G W. 1981b. Time and duration of Lunar crust formation., 52: 227–238.

Carlson R W, Lugmair G W. 1988. The age of ferroan anorthosite “60025” oldest crust on a young Moon?, 90: 119–130.

Chen E M A, Nimmo F. 2016. Tidal dissipation in the Lunar magma ocean and its effect on the early evolution of the Earth-Moon system., 275: 132–142.

Compston W, Foster J J, Gray C M. 1975. Rb-Sr ages of clasts from within Boulder 1, Station 2, Apollo 17., 14(3–4): 445–462.

DePaolo D J, Wasserburg G J. 1976. Inferences about magmasources and mantle structure from variations of143Nd/144Nd., 3(12): 743–746.

Dickin A P. 2018. Extinct radionuclides — The Sm-Nd system // Dickin A P. Radiogenic Isotope Geology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 427–432.

Dunlavey D C, Seaborg G T. 1953. Alpha activity of Sm146as detected with nuclear emulsions., 92(1): 206.

Edmunson J, Borg L E, Nyquist L E, Asmerom Y. 2009. A combined Sm-Nd, Rb-Sr, and U-Pb isotopic study of Mg-suite norite 78238: Further evidence for early differentiation of the Moon., 73(2): 514–527.

Edmunson J, Nyquist L, Borg L. 2007. Sm-Nd isotopic systematics of troctolite 76335 // 38th Lunar and PlanetaryScience Conference. League City: Pergamon Press: 1962– 1963.

Elkins-Tanton L T, Burgess S, Yin Q Z. 2011. The Lunar magma ocean: Reconciling the solidification process with Lunar petrology and geochronology., 304(3–4): 326–336.

Friedman A M, Milsted J, Metta D, Henderson D, Lerner J, Harkness A L, Rok Op D J. 1966. Alpha decay half-lives of148Gd,150Gd, and146Sm., 5: 192– 194.

Gaffney A, Borg L, Shearer C, Burger P. 2015. Chronology of 15445 norite clast B and implications for Mg-suite magmatism // 46th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. Woodlands: Pergamon Press: 1443–1444.

Gaffney A M, Borg L E. 2014a. Evidence for magma ocean solidification at 4.36 Ga from142Nd-143Nd variation in mare basalts // 45th Lunar Planetary Science Conference. Woodlands: Pergamon Press: 1449.

Gaffney A M, Borg L E. 2014b. A young solidification age for the Lunar magma ocean., 140: 227–240.

Gannoun A, Boyet M, Rizo H, El Goresy A. 2011.146Sm-142Nd systematics measured in enstatite chondrites reveals a heterogeneous distribution of142Nd in the solar nebula., 108(19): 7693–7697.

Gross J, Treiman A H, Mercer C N. 2014. Lunar feldspathic meteorites: Constraints on the geology of the Lunar highlands, and the origin of the Lunar crust., 388: 318–328.

Hamilton P, O’nions R, Bridgwater D, Nutman A. 1983. Sm-Nd studies of Archaean metasediments and metavolcanics from West Greenland and their implications for the earth’s early history., 62(2): 263–272.

Hartmann W K, Davis D R. 1975. Satellite-sized planetesimals and Lunar origin., 24: 504–515.

Hess P C, Parmentier E M. 1995. A model for the thermal and chemical evolution of the Moon’s interior: Implications for the onset of mare volcanism., 134(3): 501–514.

Jacobsen S B, Wasserburg G J. 1980. Sm-Nd isotopic evolution of chondrites., 50: 139–155.

Kinoshita N, Paul M, Kashiv Y, Collon P, Deibel C M, DiGiovine B, Greene J P, Henderson D J, Jiang C L, Marley S T, Nakanishi T, Pardo R C, Rehm K E, Robertson D, Scott R, Schmitt C, Tang X D, Vondrasek R, Yokoyama A. 2012. A shorter146Sm half-life measuredand implications for146Sm-142Nd chronology in the solar system., 335(6076): 1614–1617.

Li H Y, Zhang N, Liang Y, Wu B C, Dygert N J, Huang J S, Parmentier E M. 2019. Lunar cumulate mantle overturn: A model constrained by ilmenite rheology.:, 124(5): 1357–1378.

Lucey P, Korotev R L, Gillis J J, Taylor L A, Lawrence D, Campbell B A, Elphic R, Feldman B, Hood L L, Hunten D, Mendillo M, Noble S, Papike J J, Reedy R C, Lawson S, Prettyman T, Gasnault O, Maurice S. 2006. Understanding the Lunar surface and space-Moon interactions., 60(1): 83–219.

Lugmair G W, Marti K. 1978. Lunar initial143Nd/144Nd: Differential evolution of the Lunar crust and mantle., 39(3): 349–357.

Marks N E, Borg L E, Hutcheon I D, Jacobsen B, Clayton R N. 2014. Samarium-neodymium chronology and rubidium-strontium systematics of an Allende calcium-aluminum- rich inclusion with implications for146Sm half-life., 405: 15–24.

Marks N E, Borg L E, Shearer C K, Cassata W S. 2019. Geochronology of an Apollo 16 clast provides evidence for a basin-forming impact 4.3 billion years ago.:, 124(10): 2465–2481.

Maurice M, Tosi N, Schwinger S, Breuer D, Kleine T. 2020. A long-lived magma ocean on a young Moon., 6(28): 8949.

McLeod C L, Brandon A D, Armytage R M G. 2014. Constraints on the formation age and evolution of the Moon from142Nd-143Nd systematics of Apollo 12 basalts., 396: 179–189.

Meissner F, Schmidt-Ott W-D, Ziegeler L. 1987. Half-life and α-ray energy of146Sm., 327: 171–174.

Meyer J, Elkins-Tanton L, Wisdom J. 2010. Coupled thermal-orbital evolution of the early Moon., 208(1): 1–10.

Morison A, Labrosse S, Deguen R, Alboussière T. 2019. Timescale of overturn in a magma ocean cumulate., 516: 25–36.

Norman M D, Borg L E, Nyquist L E, Bogard D D. 2003. Chronology, geochemistry, and petrology of a ferroan noritic anorthosite clast from Descartes breccia 67215: Clues to the age, origin, structure, and impact history of the Lunar crust., 38: 645–661.

Nurmia M, Graeffe G, Valli K, Aaltonen J. 1964. Alpha activity of Sm-146., 148(6): 190.

Nyquist L, Bogard D, Yamaguchi A, Shih C-Y, Karouji Y, Ebihara M, Reese Y, Garrison D, McKay G, Takeda H. 2006. Feldspathic clasts in Yamato-86032: Remnants of the Lunar crust with implications for its formation and impact history., 70: 5990–6015.

Nyquist L, Shih C-Y, Bogard D, Yamaguchi A. 2010. Lunar crustal history from isotopic studies of Lunar anorthosites // Global Lunar Conference of the International Astronautical Federation. Beijing, 20100010840.

Nyquist L E, Shih C Y. 1992. The isotopic record of Lunar volcanism., 56(6): 2213–2234.

Nyquist L E, Wiesmann H, Bansal B, Shih C-Y, Keith J E, Harper C L. 1995.146Sm-142Nd formation interval for the Lunar mantle., 59(13): 2817–2837.

Papanastassiou D, Wasserburg G. 1975. Rb-Sr study of a Lunar dunite and evidence for early Lunar differentiates //6th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. Houston: Pergamon Press: 1467–1489.

Pernet-Fisher J, Joy K. 2016. The Lunar highlands: Old crust, new ideas., 57(1): 26–30.

Qian Y B, Ren Z Z. 2014. Half-lives ofdecay from natural nuclides and from superheavy elements., 738: 87–91.

Rankenburg K, Brandon A D, Neal C R. 2006. Neodymium isotope evidence for a chondritic composition of the Moon., 312(5778): 1369–1372.

Reiners P W, Carlson R W, Renne P R, Cooper K M, Granger D E, McLean N M, Schoene B. 2017. Extinct radionuclide chronology // Reiners P W, Carlson R W, Renne P R, Cooper K M, Granger D E, McLean N M, Schoene B. Geochronology and Thermochronology. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons: 421–443.

Ringwood A. 1960. Some aspects of the thermal evolution of the earth., 20(3–4): 241–259.

Ruskol E. 1972. The origin of the Moon. III. Some aspects of the dynamics of the circumterrestrial swarm., 15(4): 646–654.

Schaefer L, Elkins-Tanton L T. 2018. Magma oceans as a critical stage in the tectonic development of rocky planets.:,, 376, 20180109.

Shearer C K, Elardo S M, Petro N E, Borg L E, McCubbin F M. 2015. Origin of the Lunar highlands Mg-suite: An integrated petrology, geochemistry, chronology, and remote sensing perspective., 100(1): 294–325.

Shearer C K, Hess P C, Wieczorek M A, Pritchard M E, Parmentier E M, Borg L E, Longhi J, Elkins-Tanton L T, Neal C R, Antonenko I, Canup R M, Halliday A N, Grove T L, Hager B H, Lee D C, Wiechert U. 2006. Thermal and magmatic evolution of the Moon., 60: 365–518.

Shih C-Y, Nyquist L E, Dasch E J, Bogard D D, Bansal B M, Wiesmann H. 1993. Ages of pristine noritic clasts from Lunar breccias 15445 and 15455., 57: 915–931.

Sio C K, Borg L E, Cassata W S. 2020. The timing of Lunar solidification and mantle overturn recorded in ferroan anorthosite 62237., 538: 116–219.

Snyder G A, Taylor L A, Halliday A N. 1995. Chronology and petrogenesis of the Lunar highlands alkali suite: Cumulates from KREEP basalt crystallization., 59(6): 1185–1203.

Sprung P, Kleine T, Scherer E E. 2013. Isotopic evidence for chondritic Lu/Hf and Sm/Nd of the Moon., 380: 77–87.

Urey H C. 1966. The capture hypothesis of the origin of the Moon // Marsden B G, Cameron A G W. The Earth-Moon System. Boston: Springer: 210–212.

Villa I M, Holden N E, Possolo A, Ickert R B, Hibbert D B, Renne P R. 2020. IUPAC-IUGS recommendation on the half-lives of147Sm and146Sm., 285: 70–77.

Warren P H, Wasson J T. 1979. The origin of KREEP., 17(1): 73–88.

Wieczorek M A. 2006. The constitution and structure of the Lunar interior., 60(1): 221–364.

Wieczorek M A, Jolliff B L, Khan A, Pritchard M E, Weiss B P, Williams J G, Hood L L, Righter K, Neal C R, Shearer C K, McCallum I S, Tompkins S, Hawke B R, Peterson C, Gillis J J, Bussey B. 2006. The constitution and structure of the Lunar interior., 60(1): 221–364.

Wood J A, Dickey J S, Marvin U B, Powell B N. 1970. Lunar anorthosites and a geophysical model of the Moon //Apollo 11 Lunar Science Conference. Houston: Pergamon Press: 965–988.

Xu X Q, Hui H J, Chen W, Huang S C, Neal C R, Xu X S. 2020. Formation of Lunar highlands anorthosites., 536: 116–138.

Zhang B D, Lin Y T, Moser D E, Warren P H, Hao J L, Barker I R, Shieh S R, Bouvier A. 2021. Timing of Lunar Mg-suite magmatism constrained by SIMS U-Pb dating of Apollo norite 78238., 569, 117046.

Zhang N, Ding M, Zhu M-H, Li H, Li H C, Yue Z Y. 2022. Lunar compositional asymmetry explained by mantle overturn following the South Pole-Aitken impact., 15(1): 37–41.

Application of the Sm-Nd isotopic system in the early evolution of the Moon

XU Yuming1, 2, WANG Guiqin1, 3*, YANG Zhen1, 2, ZENG Yuling1, 2

(1. State Key Laboratory of Isotope Geochemistry, Guangzhou Institute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou 510640, Guangdong, China; 2. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China; 3. CAS Center for Excellence in Comparative Planetology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Hefei 230026, Anhui, China)

The formation and evolution of the Moon have essential implications for the evolution of terrestrial planets in the solar system. The Sm-Nd isotopic system is a unique tracing and dating tool that can be used to study the formation of the Moon and the early crystallization and differentiation of the Lunar magma ocean. This study introduces the principle of chronological application of147Sm-143Nd and146Sm-142Nd systematics and reviews the research on the Sm-Nd isotopic system applied to Lunar ferroan anorthosites, Mg suite, alkali-suite, KREEP, and mare basalts. The latest results show that the Moon globally/nearly globally experienced an equilibrium of the Sm-Nd isotopic system at about 4.35 Ga. However, the interpretation of this equilibrium event is still controversial. There are three plausible explanations: (1) the primitive Lunar magma ocean formed at 4.35 Ga and subsequently cooled and differentiated rapidly; (2) the Lunar magma ocean experienced a long period of cooling and differentiation, with the process ending at 4.35 Ga; (3) a global event occurred on the Moon at 4.35 Ga, which caused the equilibrium reset of Sm-Nd system. In addition, large variations in ε142Nd values (from −0.19 to −0.01) have been reported for bulk Lunar silicates. Therefore, the previous view that the initial composition of the Moon is consistent with the chondritic composition (142Nd=−0.19) has been questioned. So far, the formation and evolution of the Moon are still unclear, and the Sm-Nd isotopic system is an important tool for investigating this.

Moon; Sm-Nd isotopic system; evolution process; chronology

P148; P597

A

0379-1726(2022)06-0716-12

10.19700/j.0379-1726.2022.06.009

2022-03-07;

2022-07-27

国家国防科技工业局项目(D020203)、中国科学院战略性先导科技专项(B类)(XDB41020305)、国家自然科学基金项目(42073061)和国家重点研发计划(2020YFA0714804)联合资助。

徐玉明(1996–), 男, 博士研究生, 地球化学专业。E-mail: xuyuming@gig.ac.cn

王桂琴(1968–), 女, 高级工程师, 从事质谱仪器应用开发和宇宙化学研究。E-mail: guiqinwang@gig.ac.cn