特发性低促性腺激素性性腺功能减退症FGFR1与CEP290基因变异研究

王姗姗,赵琬怡,吴慧潇,舒梦,袁嘉欣,方丽,徐潮

研究报告

特发性低促性腺激素性性腺功能减退症与基因变异研究

王姗姗1,赵琬怡2,吴慧潇2,舒梦2,袁嘉欣2,方丽2,徐潮1

1. 山东第一医科大学附属山东省立医院内分泌与代谢性疾病科,山东省临床医学研究院内分泌代谢研究所,山东省内分泌与脂质代谢重点实验室,济南 250021 2. 山东大学附属山东省立医院内分泌与代谢性疾病科,山东省临床医学研究院内分泌代谢研究所,山东省内分泌与脂质代谢重点实验室,济南 250021

特发性低促性腺激素性性腺功能减退症(idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, IHH)是由于促性腺激素释放激素(gonadotropin-releasing hormone, GnRH)缺乏或作用缺陷引起以性腺发育不良为特征的内分泌罕见病。依据是否并发嗅觉障碍可以分为嗅觉正常特发性低促性腺激素性性腺功能减退症(normosmic isolated hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, nIHH)和嗅觉障碍的卡尔曼综合征(Kallmann syndrome, KS)。本研究收集并分析了1例nIHH散发病例的临床资料。全外显子测序证实患儿同时携带基因变异(c.2008G>A, p.E670K)和遗传于其母亲的基因变异(c.964G>A, p.D322N)。生物信息学分析发现基因突变(c.2008G>A)改变FGFR1蛋白TK2结构域,影响FGFR1受体的功能及下游细胞信号转导通路的激活。基因(c.964G>A)可能影响GnRH神经元的正确迁徙途径导致IHH,CEP290蛋白与FGFR1蛋白之间存在相互作用。本研究结果扩展了IHH致病基因表达谱,为探究IHH的致病机制提供了新的方向,并为该类疾病的临床精准诊疗提供了借鉴和参考。

特发性低促性腺激素性性腺功能减退症;;;生物信息学分析

特发性低促性腺激素性性腺功能减退症(idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, IHH)是由于促性腺激素释放激素(gonadotropin-releasing hormone, GnRH)缺乏或作用缺陷引起以性腺发育不良为特征的一种非常罕见的遗传异质性疾病[1~3]。根据是否存在嗅觉障碍,分为具有嗅觉障碍的卡尔曼综合征(Kallmann syndrome, KS)及嗅觉正常的特发性促性腺激素性性腺功能减退(normosmic isolated hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, nIHH)[2,4]。IHH是一类遗传异质性疾病,包括多种遗传方式:X连锁隐性遗传、常染色体显性遗传和常染色体隐性遗传等[5~7]。随着测序技术的进步,目前已经发现至少有50个基因与IHH的发病有关:、和等[8~10]。随着研究的深入,研究发现IHH可由2个或2个以上的基因突变引起,称为寡基因性,且在约有10%~20%的IHH患者或家系可检测到同时存在多个致病基因[11],具有明显的临床异质性。GnRH神经元的缺陷会引起不同程度的生殖系统临床表现[12,13],还伴发其他少见的非生殖系统表型:唇腭裂、孤立肾、骨骼畸形或牙齿发育不良、较特异的双手连带动作、感觉性神经耳聋、痉挛性截瘫、尿道下裂及肥胖等[14~16]。本研究描述了同时携带和两个候选突变基因的一个nIHH散发病例,利用生物信息学软件预测了变异基因可能致病机制,并发现基因可能是IHH致病候选基因之一。

1 对象与方法

1.1 对象及家系资料收集

患儿,男,9月龄,因“阴茎长度0.5 cm,直径0.5 cm”由父母携同于2016年5月就诊于山东第一医科大学附属省立医院儿科内分泌门诊,初步诊断为“IHH”,经父母同意并签署知情同意书后,收集患者临床资料,并抽取先证者及其I级亲属的外周血,每人各收集5 mL含EDTA抗凝剂的全血和5 mL血清。本研究已通过山东第一医科大学附属省立医院伦理委员会批准。研究方案与《赫尔辛基宣言》(2013年,巴西修订版)一致。

1.2 外周血基因组DNA提取

留取家系成员的外周血,使用基因组DNA试剂盒(北京天根生化公司)提取基因组DNA,经片段化、连接接头、扩增纯化后进行全外显子组测序[17]。

1.3 全外显子组测序及Sanger验证

使用SeqCap EZ meddexome Target Enrichment Kit (Roche NimbleGen)杂交捕获人类全部基因的外显子区及旁侧内含子区域(50 bp)经洗脱和扩增纯化后,使用高通量测序仪(Illumina HiSeq)测序,使用NextGene V2.3.4软件与UCSC hg19人类参考基因组序列进行比对和鉴别遗传变异,并收集目标区域的覆盖度和平均测序深度等质量参数。受检者目标基因外显子测序区域平均测序深度151.24×,目标基因CDs覆盖度20×以上97.95%。当全外显子检出致病或可能致病变异时,实验室通过Sanger测序确保该基因编码序列的覆盖率达到 100%[18]。遗传变异的致病性评估依据美国医学遗传学与基因组学学会(American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics, ACMG)发布的《序列变异解读标准和指南》,并采用HGVS命名法。

1.4 生物信息学分析

利用Clustal Omega (http://ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/ clustalo/)进行多重序列比对[19],并通过Jalview和WebLogo(http://welogo.threepiusone.com/creat.cgi.)突变蛋白氨基酸的保守度可视化。使用EMBL-EBI分析基因(c.2008G>A, p.E670K)的突变概率。通过Mutation-Taster (http://www.mutationtaster.org/) 和PolyPhen-2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/ dbsearch.shtml)两个在线生物信息软件对突变位点进行评分,预测突变位点是否具有致病性[20,21]。利用AlphaFold在线软件(https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/)构建FGFR1野生型及突变体的三维空间结构。在线分析(http://www.vls3d.com/)FGFR1突变蛋白对下游信号信号分子影响。使用InBio Map(https://www. intomics.com/inbio/map/)构建蛋白质–蛋白质相互作用网络。所有模型均在PyMOL软件(version 1.3)上可视化。

2 结果与分析

2.1 先证者临床特点及家系分析

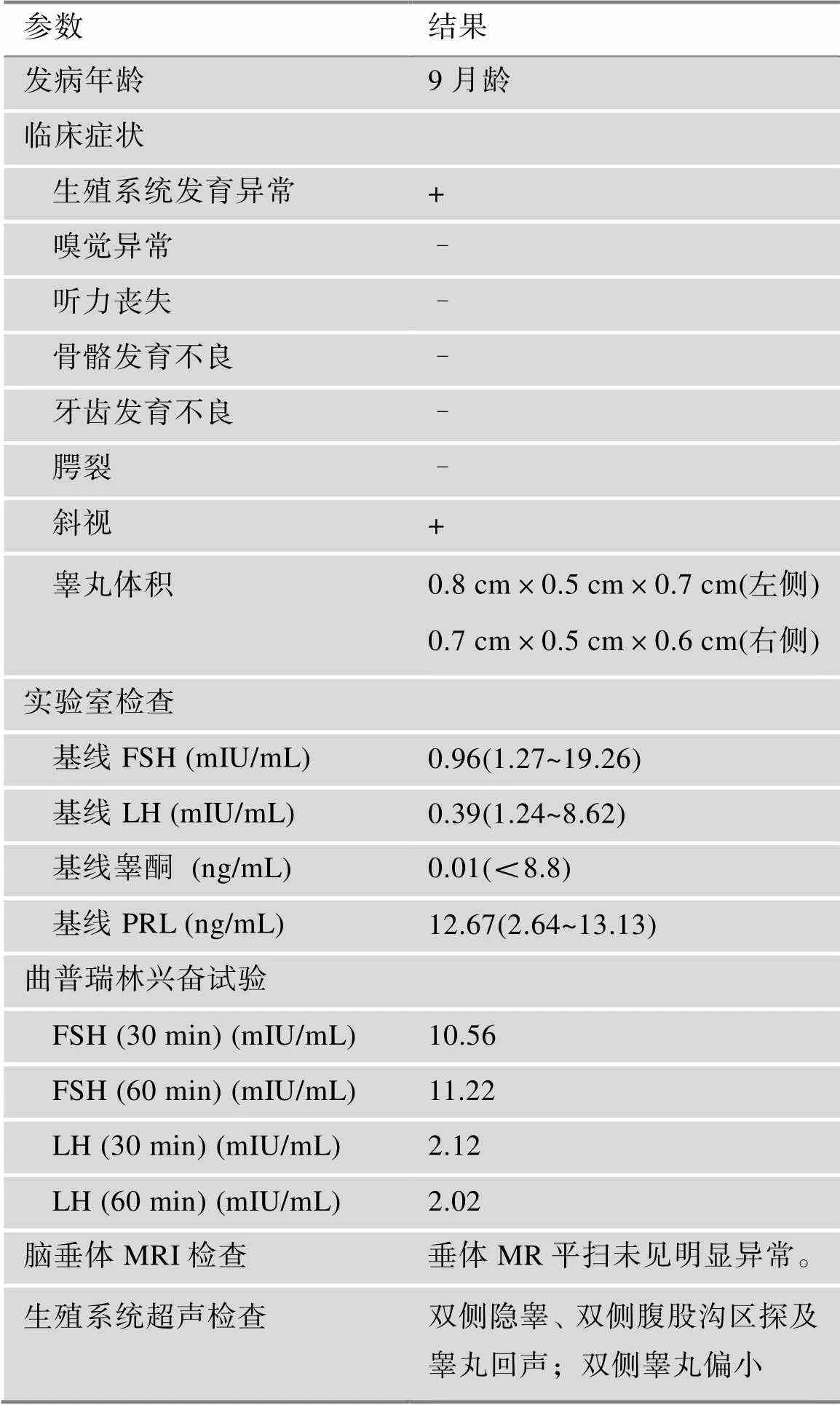

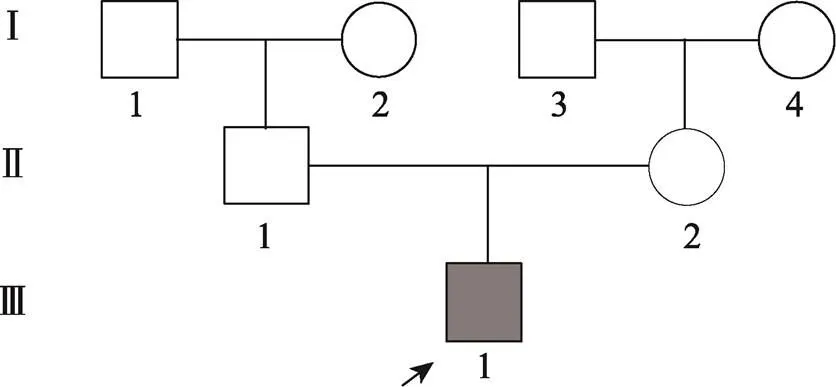

收集的该nIHH三代家系,共7名成员。先证者9个月时因“阴茎长度0.5 cm,直径0.5 cm”来我院就诊。该患儿基线血清FSH、LH及睾酮水平下降,曲普瑞林兴奋试验:LH峰值2.12 mIU/mL (表1)。垂体MRI未见明显异常。超声显示两侧睾丸体积均小于1 mL (表1)。染色体核型分析:46XY。截止到2022年3月,先证者嗅觉正常,有轻微斜视,未有其他非生殖系统表现。其家系其余成员均未发病(图1)。

表1 nIHH先证者患者的临床特点及曲普瑞林兴奋试验

nIHH:嗅觉正常的特发性促性腺激素性性腺功能减退症;FSH:促卵泡激素;LH:促黄体生成素;PRL:催乳素;MRI:磁共振成像。

图1 nIHH先证者家系分析

□:正常男性;○:正常女性;■:nIHH男性。

2.2 先证者及家系成员基因检测结果分析

先证者检出基因突变(c.2008G> A, p.E670K)及基因突变(c.964G>A, p.D322N)。其母亲检出基因突变(c.964G>A, p.D322N),其余家系成员均为野生型(图2)。

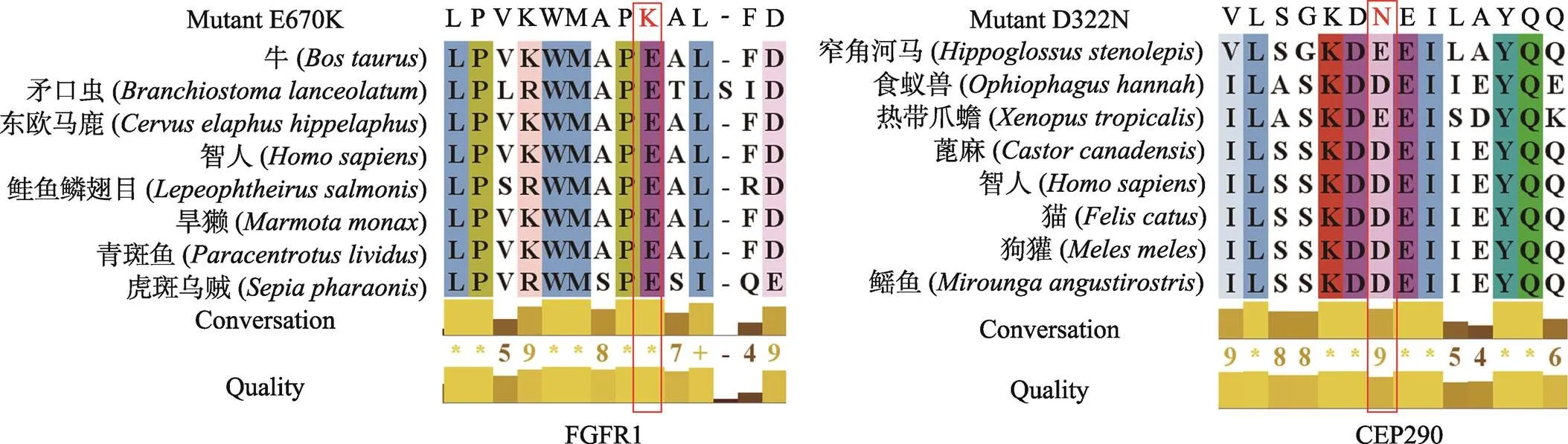

2.3 突变基因的保守性分析

利用Clustal-X软件的保守性分析结果表明,FGFR1蛋白突变(p.E670K)在同源物种间高度保守,CEP290蛋白突变(p.D322N)在同源物种间高度保守(图3)。

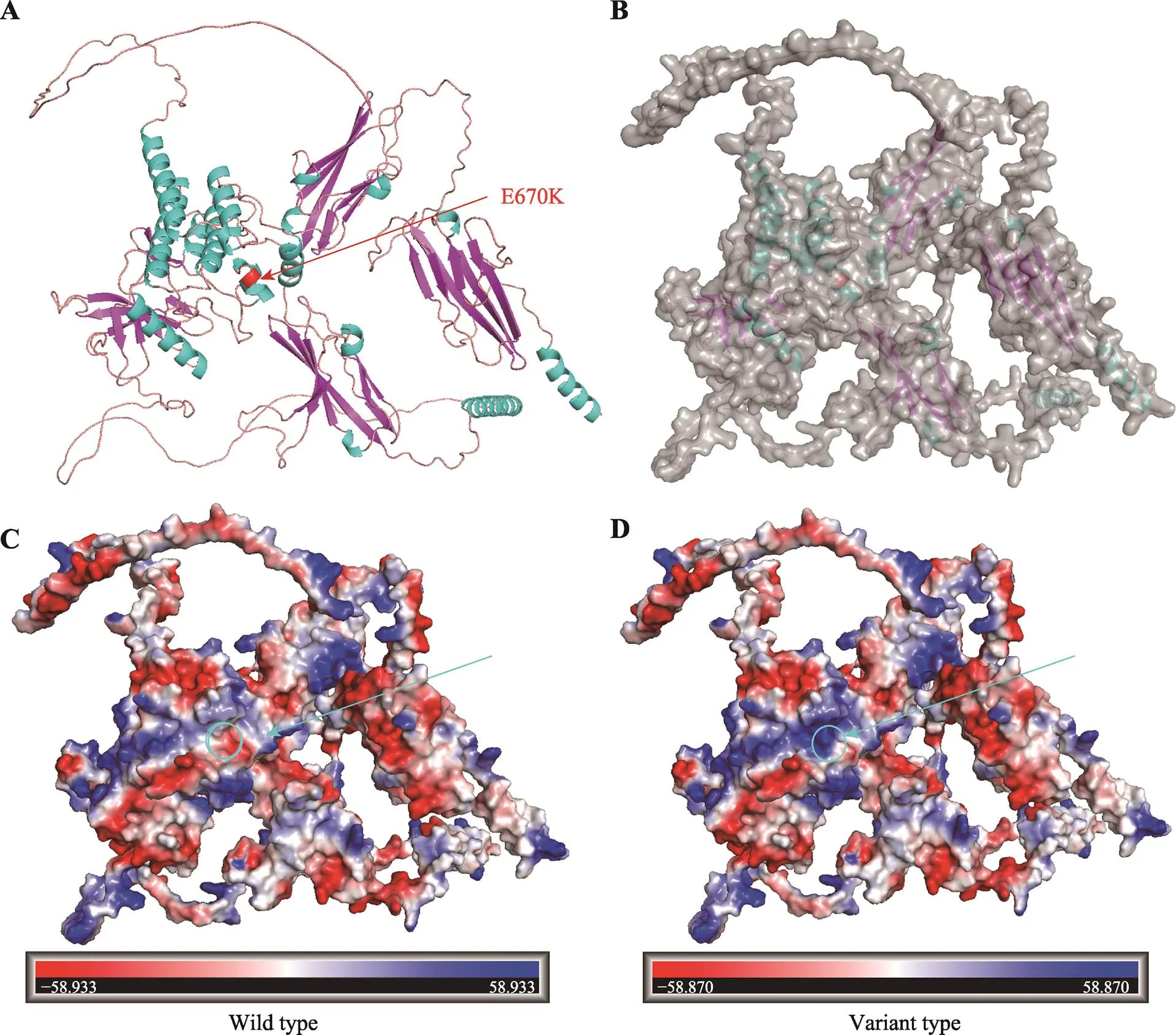

2.4 在线生物信息学软件和蛋白结构模型分析

经Alpha Fold对FGFR1蛋白质建模,该突变位点TK2结构域的α螺旋中,距离两个自磷酸位点653位酪氨酸及677位酪氨酸和623位天冬氨酸活化中心很近,所带电荷由负变正(图4A)。该结构域的表观静电势分布由正变成负(图4,C和D),进而影响表面的氢键分布、范德华力的形成,改变蛋白质三级结构,推测可能会影响正常蛋白质的功能及下游信号分子的结合。

图2 先证者及其父母FGFR1、CEP290基因测序结果

A:先证者及其父母基因测序结果;B:先证者及其父母基因测序结果。箭头所示为突变位点。

图3 FGFR1和CEP290蛋白在同源物种中多重序列比对

表2 突变位点的致病性分析

Mutation-Taster预测结果:A:Disease causing automatic (有害);D:Disease causing (可能有害);N:Polymorphism (可能无害);P:Polymorphism automatic (无害)。PolyPhen-2预测结果:D:Probably damaging (很可能有害,分值≥0.957);P:Possibly damaging (可能有害,分值0.453~0.956);B:Benign (无害,分值≤0.452)。

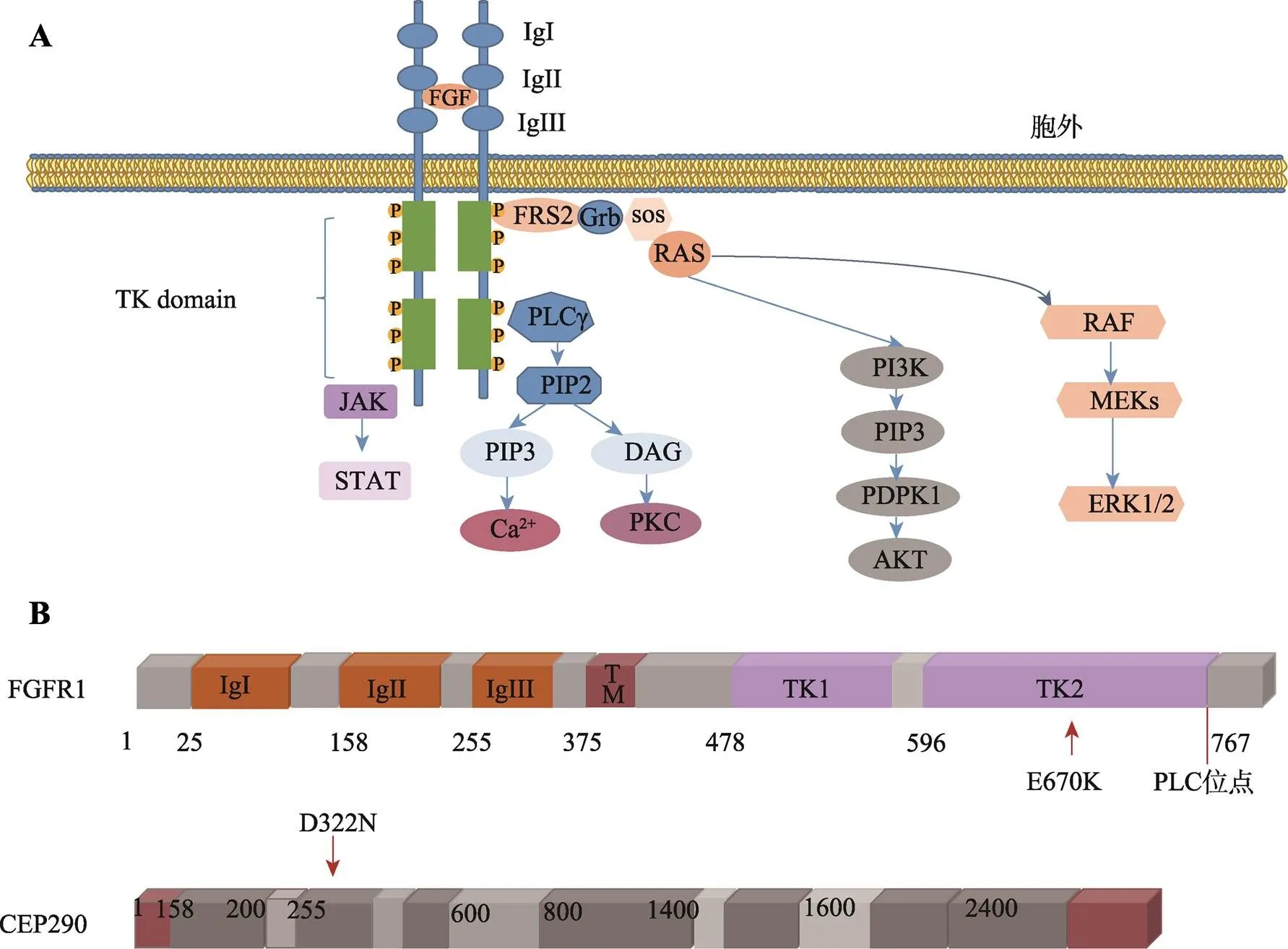

2.5 FGFR1突变预测可能会影响下游信号传导通路

活化后的FGFR1可激活下游RAS-RAF-MAPK、PI3K-AKT、STAT和PLC途径等细胞信号传导通路(图6A),FGFR1蛋白变异(p.E670K)位于TK2结构域(图6B),是下游信号分子的重要结合部位。本研究利用在线生物信息学工具进一步验证FGFR1蛋白变异(p.E670K)是否会影响下游信号传导通路。结果发现该突变会影响JAK2、STAT3下游信号分子的结合(图7,A和B),在ERK1、ERK2也发现了相似的结果(图7,C和D)。由此推测FGFR1蛋白变异(p.E670K)会影响下游信号传导通路的激活。

2.6 CEP290与FGFR1蛋白质相互作用网络有关

本文利用在线生物信息学软件预测基因突变(c.2008G>A)是IHH的致病突变,该先证者中同时检测到基因突变,除本研究利用生物信息学软件预测其可能具有致病性外,无法获得与CHH发病相关的确切证据。

图4 FGFR1蛋白发生E到K变异的概率预测

图5 野生型及突变型FGFR1蛋白建模

A:FGFR1突变蛋白的卡通模型;B:FGFR1突变蛋白表面结构;C:野生型FGFR1蛋白静电势模型;D:突变型FGFR1蛋白静电势模型。红色条带代表突变位置。圆圈标注为突变位点。突变蛋白圆圈标注点静电势由红色变为蓝色代表由负电变成正电。

保守性分析发现CEP290蛋白变异(p.D322N)位于高度保守序列。既往研究已经证实,CEP290是嗅觉上皮细胞纤毛发生起始所必需的[22],对GnRH神经元的正确迁徙和最终定位至关重要。本研究推测CEP290蛋白可能与FGFR1蛋白存在相互作用。为了验证这一猜想,本文利用InBio Map构建了FGFR1蛋白质相互作用网络,发现FGFR1蛋白可能通过FGF8、IL17RD、FLRT1、PIK3、S100B等信号分子与CEP290蛋白质相互作用(图8),这些信号分子对细胞周期、神经元细胞增殖、细胞分化、细胞凋亡、基因表达等至关重要。

3 讨论

IHH是一种由GnRH合成、分泌或作用功能障碍引起的具有遗传和临床异质性的疾病[3]。目前仅在不到10%的KS和nIHH患者中鉴定出了基因突变[12,23,24]。基因位于8p11.23,由24个外显子组成,编码822 种氨基酸,主要通过FGF8/FGFR1信号通路在胚胎嗅神经和GnRH神经元的形成、存活和迁移中起着关键作用[25]。基因是纤毛病的致病基因之一,在嗅觉上皮的发育中具有关键作用[26]。本文首次报道了一个同时携带基因变异(c.2008G>A, p.E670K)和基因突变(c.964G>A, p.D322N)的一个nIHH散发病例,仅先证者母亲携带有基因(c.964G>A, p.D322N)杂合突变,其父亲体内未检测到任何突变。本文初步明确了基因突变(c.2008G>A, p.E670K)的致病机制,并发现一个新的候选基因基因突变(c.964G>A, p.D322N),为临床精准诊疗提供了科学依据。

图6 FGFR1下游重要细胞信号传导通路及FGFR1和CEP290突变示意图

A:FGFR1下游重要细胞信号传导通路。成纤维细胞生长因子(FGF)与FGFR1结合后可促进两个相邻的单链FGFR1聚集、活化,活化后的FGFR1可进一步激活下游RAS–RAF–MAPK、PI3K–AKT、STAT和PLC途径等细胞信号传导通路。B:FGFR1(p.E670K)及CEP290(p.D322N)蛋白突变示意图。

FGFR1蛋白作为成纤维细胞生长因子受体家族的基本成员,由3个部分组成:细胞外成纤维生长因子(fibroblast growth factor, FGF)结合域、单次跨膜的疏水α螺旋区以及含有酪氨酸蛋白激酶活性的胞内结构域[27,28]。其中细胞外FGF结合域由3个免疫球蛋白样结构域组成(IgI、IgII、IgIII),是与配体结合的关键位点[25]。FGF与FGFR1结合后可促进两个相邻的单链FGFR1聚集、活化,活化后的FGFR1可进一步激活下游RAS-RAF-MAPK、PI3K-AKT、STAT和PLC途径等细胞信号传导通路,它们参与调控器官发育、血管新生、细胞增殖、迁移、抗凋亡等多种生物学过程[29-31]。本研究利用生物在线软件将该突变评估为具有致病性。蛋白质建模显示该突变将位于670号氨基酸由谷氨酸替换为赖氨酸,定位于酪氨酸激酶活性的细胞内结构域,位于同源物种的高度保守序列。突变使得该结构域的表观静电势分布由正变成负,影响了表面的氢键分布、范德华力的形成,改变了蛋白质正常的三级结构,影响FGFR1蛋白功能缺失。由于TK结构域是下游信号分子的重要结合部位。生物信息软件预测FGFR1突变蛋白会影响JAK2、STAT3 ERK1、ERK2下游信号分子的结合。因此我们推测该突变造成蛋白质的功能,并且影响下游信号转导通路的激活[32],最终导致GnRH神经元发育、迁移异常。

A:FGFR1突变蛋白与JAK2信号分子相互作用模型;B:FGFR1突变蛋白与STAT3信号分子相互作用模型;C:FGFR1突变蛋白与ERK1信号分子相互作用模型;D:FGFR1突变蛋白与ERK2信号分子相互作用模型。红色代表突变位点。

据报道,约有10%的KS患者中可发现基因缺陷。白种人队列中,家族性病例的患病率为3%,散发性病例为6%[12]。在日本队列中,散发性和家族性病例中突变的频率分别为11%和9%[33]。然而在nIHH患者中,突变的频率目前尚不清楚。最近在134例nIHH病例中也检测到7%的基因功能缺失突变[34]。但是基因突变类型与其临床表型并无明确的相关性[35]。基因表现出明显的“不完全外显性”,在同一家系的患者或者不同家系的不同成员中,携带基因突变的IHH患者表现出不同程度的嗅觉异常和性腺功能减退,既可以导致KS,还可引起nIHH和青春期发育延迟[23,36]。约有10%~20%的IHH患者或家系中存在多个IHH相关突变基因。既往报道同时携带FGFR1(p.Gly348Glu)、IL17RD(p.Gly701Ser)和RUVBL2(p.Arg71Trp)突变IHH患者仅表现出了唇腭裂非生殖系统表型[35]。已经被证实是IHH的致病基因。相比之下,仅携带突变(p.Arg209Cys)的患者表现出唇腭裂、牙齿畸形和高弓型腭裂等更严重非生殖系统表型,生殖系统表型更为严重[35]。Akkus等[37]之前也报道了1名携带相同突变(p.Arg209Cys)的14岁男性KS患者,患者表现出小阴茎,无法勃起等生殖系统症状,并未出现任何非生殖系统的表现。临床表现的异质性可能是二基因或寡基因遗传的结果。最近通过动物模型揭示了FGFR1 FGF8双杂合基因突变和在斑马鱼中同时存在IL-17受体D和变异,均产生了GnRH神经元缺失的表型[27]。IHH患者的表型也受到表观遗传学和环境因素的影响[38]。与既往报道的携带基因突变的KS患者相比[36,39,40],我们的患者临床表型较轻。也有携带相同的基因突变的IHH双胞胎表达不同临床表型的例子[41~43]。总之,IHH具有低外显率和可变表达的复杂的遗传异质性。多种基因突变共存、环境因素、表观遗传修饰可能导致其可变的疾病表现[44,45]。此外nIHH总体患病率约110/1,000,000,且大部分患者都是成年发病,故多数延迟诊断而错过最佳治疗时机。目前仅有不到40%的患者发病可以由已发现的基因突变来解释[46~48],还有许多与IHH发病有关的候选基因尚未发现[36]。

CEP290是一个进化保守的纤毛过渡区蛋白,其突变会导致多种纤毛病[49]。在基因突变的小鼠模型中发现CEP290蛋白在细胞分裂、保护肾脏、维持视网膜稳态过程起着重要的作用[50]。携带基因突变的先天性黑蒙症或梅克尔–格鲁贝尔综合征患者中,除了存在嗅觉异常外,还发现了GnRH神经元的缺陷[51]。但本研究仅仅通过生物信息学分析初步预测基因有可能在基因导致nIHH的致病机制中发挥作用,但具体机制尚不明确,后续我们将会完善体外功能实验。

与既往报道基因突变的nIHH患者相比,该先证者的表型较轻。且在随访期间,并未出现嗅觉丧失及其他非生殖系统症状。本研究推测基因突变的不完全外显可能为该患儿未表现出其他临床症状的重要原因[52];此外患儿年龄较小,生长发育不完全,应定期随访有无其他症状的发生。

综上所述,由于大多数IHH患者目前还没有明确的分子机制,需要进一步研究。在此基础上,本研究为阐明基因变异的分子机制提供了令人信服的证据,并推测有可能是nIHH新的致病基因,为临床精准诊疗提供了科学依据。

[1] Erbaş İM, Paketçi A, Acar S, Kotan LD, Demir K, Abacı A, Böber E. A nonsense variant in FGFR1: a rare cause of combined pituitary hormone deficiency., 2020, 33(12): 1613–1615.

[2] Bianco SDC, Kaiser UB. The genetic and molecular basis of idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism., 2009, 5(10): 569–576.

[3] Liu QX, Yin XQ, Li P. Clinical, hormonal, and genetic characteristics of 25 Chinese patients with idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism., 2022, 22(1): 30.

[4] Seminara SB, Hayes FJ, Crowley WF. Gonadotropin- releasing hormone deficiency in the human (idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and Kallmann's syndrome): pathophysiological and genetic considerations., 1998, 19(5): 521–539.

[5] Teixeira L, Guimiot F, Dodé C, Fallet-Bianco C, Millar RP, Delezoide AL, Hardelin JP. Defective migration of neuroendocrine GnRH cells in human arrhinencephalic conditions., 2010, 120(10): 3668–3672.

[6] Forni PE, Taylor-Burds C, Melvin VS, Williams T, Wray S. Neural crest and ectodermal cells intermix in the nasal placode to give rise to GnRH-1 neurons, sensory neurons, and olfactory ensheathing cells., 2011, 31(18): 6915–6927.

[7] Pitteloud N, Durrani S, Raivio T, Sykiotis GP. Complex genetics in idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism., 2010, 39: 142–153.

[8] Stamou MI, Brand H, Wang M, Wong I, Lippincott MF, Plummer L, Crowley WF, Talkowski M, Seminara S, Balasubramanian R. Prevalence and phenotypic effects of copy number variants in isolated hypogonadotropic hypogonadism., 2022, 107(8): 2228–2242.

[9] Stamou MI, Cox KH, Crowley WF. Discovering genes essential to the hypothalamic hegulation of human reproduction using a human disease model: adjusting to life in the "-omics" era., 2015, 36(6): 603– 621.

[10] Beate K, Joseph N, Nicolas de R, Wolfram K. Genetics of isolated hypogonadotropic hypogonadism: role of GnRH receptor and other genes., 2012, 2012: 147893.

[11] Quaynor SD, Kim HG, Cappello EM, Williams T, Chorich LP, Bick DP, Sherins RJ, Layman LC. The prevalence of digenic mutations in patients with normosmic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and Kallmann syndrome., 2011, 96(6): 1424–1430. e6.

[12] Dodé C, Levilliers J, Dupont JM, De Paepe A, Le Dû N, Soussi-Yanicostas N, Coimbra RS, Delmaghani S, Compain-Nouaille S, Baverel F, Pêcheux C, Le Tessier D, Cruaud C, Delpech M, Speleman F, Vermeulen S, Amalfitano A, Bachelot Y, Bouchard P, Cabrol S, Carel JC, de Waal HDV, Goulet-Salmon B, Kottler ML, Richard O, Sanchez-Franco F, Saura R, Young J, Petit C, Hardelin JP. Loss-of-function mutations in FGFR1 cause autosomal dominant Kallmann syndrome., 2003, 33(4): 463–465.

[13] Boyar RM, Wu RH, Kapen S, Hellman L, Weitzman ED, Finkelstein JW. Clinical and laboratory heterogeneity in idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism., 1976, 43(6): 1268–1275.

[14] Boehm U, Bouloux PM, Dattani MT, de Roux N, Dodé C, Dunkel L, Dwyer AA, Giacobini P, Hardelin JP, Juul A, Maghnie M, Pitteloud N, Prevot V, Raivio T, Tena- Sempere M, Quinton R, Young J. Expert consensus document: European Consensus Statement on congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism—pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment., 2015, 11(9): 547–564.

[15] Lewkowitz-Shpuntoff HM, Hughes VA, Plummer L, Au MG, Doty RL, Seminara SB, Chan YM, Pitteloud N, Crowley WF, Balasubramanian R. Olfactory phenotypic spectrum in idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism: pathophysiological and genetic implications., 2012, 97(1): E136–E144.

[16] Xu H, Niu YH, Wang T, Liu SM, Xu H, Wang SG, Liu JH, Ye ZQ. Novel FGFR1 and KISS1R mutations in Chinese Kallmann syndrome males with cleft lip/palate., 2015, 2015: 649698.

[17] Ying H, Sun Y, Wu HX, Jia WY, Guan QB, He Z, Gao L, Zhao JJ, Ji YM, Li GM, Xu C. Posttranslational modification defects in fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 as a reason for normosmic isolated hypogonadotropic hypogonadism., 2020, 2020: 2358719.

[18] Luo HJ, Zheng RZ, Zhao YG, Wu JY, Li J, Jiang F, Chen DN, Zhou XT, Li JD. A dominant negative FGFR1 mutation identified in a Kallmann syndrome patient., 2017, 621: 1–4.

[19] Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. Multiple sequence alignment using ClustalW and ClustalX., 2002, Chapter 2: Unit 2. 3.

[20] Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, Kondrashov AS, Sunyaev SR. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations., 2010, 7(4): 248–249.

[21] Schwarz JM, Rödelsperger C, Schuelke M, Seelow D. MutationTaster evaluates disease-causing potential of sequence alterations., 2010, 7(8): 575–576.

[22] Uytingco CR, Green WW, Martens JR. Olfactory loss and dysfunction in ciliopathies: molecular mechanisms and potential therapies., 2019, 26(17): 3103–3119.

[23] Pitteloud N, Meysing A, Quinton R, Acierno JS, Dwyer AA, Plummer L, Fliers E, Boepple P, Hayes F, Seminara S, Hughes VA, Ma JH, Bouloux P, Mohammadi M, Crowley WF. Mutations in fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 cause Kallmann syndrome with a wide spectrum of reproductive phenotypes., 2006, 254–255: 60–69.

[24] Hébert JM, Lin M, Partanen J, Rossant J, Mcconnell SK. FGF signaling through FGFR1 is required for olfactory bulb morphogenesis., 2003, 130(6): 1101–1111.

[25] Falardeau J, Chung WCJ, Beenken A, Raivio T, Plummer L, Sidis Y, Jacobson-Dickman EE, Eliseenkova AV, Ma JH, Dwyer A, Quinton R, Na S, Hall JE, Huot C, Alois N, Pearce SHS, Cole LW, Hughes V, Mohammadi M, Tsai P, Pitteloud N. Decreased FGF8 signaling causes deficiency of gonadotropin-releasing hormone in humans and mice., 2008, 118(8): 2822–2831.

[26] Mcewen DP, Koenekoop RK, Khanna H, Jenkins PM, Lopez I, Swaroop A, Martens JR. Hypomorphic CEP290/ NPHP6 mutations result in anosmia caused by the selective loss of G proteins in cilia of olfactory sensory neurons., 2007, 104(40): 15917– 15922.

[27] Tata BK, Chung WCJ, Brooks LR, Kavanaugh SI, Tsai PS. Fibroblast growth factor signaling deficiencies impact female reproduction and kisspeptin neurons in mice., 2012, 86(4): 119.

[28] Lee PL, Johnson DE, Cousens LS, Fried VA, Williams LT. Purification and complementary DNA cloning of a receptor for basic fibroblast growth factor., 1989, 245(4913): 57–60.

[29] Mohammadi M, Olsen SK, Ibrahimi OA. Structural basis for fibroblast growth factor receptor activation., 2005, 16(2): 107–137.

[30] Goetz R, Mohammadi M. Exploring mechanisms of FGF signalling through the lens of structural biology., 2013, 14(3): 166–180.

[31] Sykiotis GP, Plummer L, Hughes VA, Au M, Durrani S, Nayak-Young S, Dwyer AA, Quinton R, Hall JE, Gusella JF, Seminara SB, Crowley WF, Pitteloud N. Oligogenic basis of isolated gonadotropin-releasing hormone deficiency., 2010, 107(34): 15140–15144.

[32] Eswarakumar VP, Lax I, Schlessinger J. Cellular signaling by fibroblast growth factor receptors., 2005, 16(2): 139–149.

[33] Sato N, Katsumata N, Kagami M, Hasegawa T, Hori N, Kawakita S, Minowada S, Shimotsuka A, Shishiba Y, Yokozawa M, Yasuda T, Nagasaki K, Hasegawa D, Hasegawa Y, Tachibana K, Naiki Y, Horikawa R, Tanaka T, Ogata T. Clinical assessment and mutation analysis of Kallmann syndrome 1 (KAL1) and fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1, or KAL2) in five families and 18 sporadic patients., 2004, 89(3): 1079–1088.

[34] Raivio T, Sidis Y, Plummer L, Chen HB, Ma JH, Mukherjee A, Jacobson-Dickman E, Quinton R, Van Vliet G, Lavoie H, Hughes VA, Dwyer A, Hayes FJ, Xu SY, Sparks S, Kaiser UB, Mohammadi M, Pitteloud N. Impaired fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 signaling as a cause of normosmic idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism., 2009, 94(11): 4380–4390.

[35] Wang DQ, Niu YH, Tan JH, Chen YW, Xu H, Ling Q, Gong JN, Ling L, Wang JX, Wang T, Liu JH. Combined in vitro and in silico analyses of FGFR1 variants: genotype-phenotype study in idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism., 2020, 98(4): 341–352.

[36] Miraoui H, Dwyer AA, Sykiotis GP, Plummer L, Chung W, Feng BH, Beenken A, Clarke J, Pers TH, Dworzynski P, Keefe K, Niedziela M, Raivio T, Crowley WF, Seminara SB, Quinton R, Hughes VA, Kumanov P, Young J, Yialamas MA, Hall JE, Van Vliet G, Chanoine JP, Rubenstein J, Mohammadi M, Tsai PS, Sidis Y, Lage K, Pitteloud N. Mutations in FGF17, IL17RD, DUSP6, SPRY4, and FLRT3 are identified in individuals with congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism., 2013, 92(5): 725–743.

[37] Akkuş G, Kotan LD, Durmaz E, Mengen E, Turan İ, Ulubay A, Gürbüz F, Yüksel B, Tetiker T, Topaloğlu AK. Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism due to novel FGFR1 mutations., 2017, 9(2): 95–100.

[38] Vezzoli V, Duminuco P, Bassi I, Guizzardi F, Persani L, Bonomi M. The complex genetic basis of congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism., 2016, 41(2): 223–239.

[39] Costa-Barbosa FA, Balasubramanian R, Keefe KW, Shaw ND, Al-Tassan N, Plummer L, Dwyer AA, Buck CL, Choi JH, Seminara SB, Quinton R, Monies D, Meyer B, Hall JE, Pitteloud N, Crowley WF. Prioritizing genetic testing in patients with Kallmann syndrome using clinical phenotypes., 2013, 98(5): E943–E953.

[40] Amato LGL, Montenegro LR, Lerario AM, Jorge AAL, Guerra Junior G, Schnoll C, Renck AC, Trarbach EB, Costa EMF, Mendonca BB, Latronico AC, Silveira LFG. New genetic findings in a large cohort of congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism., 2019, 181(2): 103–119.

[41] Choe J, Kim JH, Kim YA, Lee J. Dizygotic twin sisters with normosmic idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism caused by an FGFR1 gene variant., 2020, 25(3): 192–197.

[42] Hermanussen M, Sippell WG. Heterogeneity of Kallmann's syndrome., 1985, 28(2): 106–111.

[43] Hipkin LJ, Casson IF, Davis JC. Identical twins discordant for Kallmann's syndrome., 1990, 27(3): 198–199.

[44] Bonomi M, Libri DV, Guizzardi F, Guarducci E, Maiolo E, Pignatti E, Asci R, Persani L, Idiopathic Central Hypogonadism Study Group of the Italian Societies of Endocrinology and Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes. New understandings of the genetic basis of isolated idiopathic central hypogonadism., 2012, 14(1): 49–56.

[45] Network for Central Hypogonadism (Network Ipogonadismo Centrale, NICe) of Italian Societies of Endocrinology (SIE), of Andrology and Sexual Medicine (SIAMS) and of Peadiatric Endocrinology and Diabetes (SIEDP). Kallmann's syndrome and normosmic isolated hypogonadotropic hypogonadism: two largely overlapping manifestations of one rare disorder., 2014, 37(5): 499–500.

[46] Bhangoo A, Jacobson-Dickman E. The genetics of idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism: unraveling the biology of human sexual development., 2009, 6(3): 395–404.

[47] Bonomi M, Libri DV, Guizzardi F, Guarducci E, Maiolo E, Pignatti E, Asci R, Persani L, Idiopathic Central Hypogonadism Study Group of the Italian Societies of Endocrinology and Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes. New understandings of the genetic basis of isolated idiopathic central hypogonadism., 2012, 14(1): 49–56.

[48] Kim SH. Congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and Kallmann syndrome: past, present, and future., 2015, 30(4): 456–466.

[49] Coppieters F, Lefever S, Leroy BP, De Baere E. CEP290, a gene with many faces: mutation overview and presentation of CEP290base., 2010, 31(10): 1097–1108.

[50] Valente EM, Silhavy JL, Brancati F, Barrano G, Krishnaswami SR, Castori M, Lancaster MA, Boltshauser E, Boccone L, Al-Gazali L, Fazzi E, Signorini S, Louie CM, Bellacchio E, International Joubert Syndrome Related Disorders Study Group, Bertini E, Dallapiccola B, Gleeson JG. Mutations in CEP290, which encodes a centrosomal protein, cause pleiotropic forms of Joubert syndrome., 2006, 38(6): 623–625.

[51] Balasubramanian R, Dwyer A, Seminara SB, Pitteloud N, Kaiser UB, Crowley WF. Human GnRH deficiency: a unique disease model to unravel the ontogeny of GnRH neurons., 2010, 92(2): 81–99.

[52] Pitteloud N, Acierno JS, Meysing A, Eliseenkova AV, Ma JH, Ibrahimi OA, Metzger DL, Hayes FJ, Dwyer AA, Hughes VA, Yialamas M, Hall JE, Grant E, Mohammadi M, Crowley WF. Mutations in fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 cause both Kallmann syndrome and normosmic idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism., 2006, 103(16): 6281–6286.

Research on the variants ofandgenes in idiopathic hypogonadotropin hypogonadism

Shanshan Wang1, Wanyi Zhao2, Huixiao Wu2, Meng Shu2, Jiaxin Yuan2, Li Fang2, Chao Xu1

Idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (IHH) is a rare endocrine disease characterized by gonadal dysplasia. According to whether the sense of smell is affected, this disorder is classified into Kallmann syndrome (KS) and normosmic isolated hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (nIHH). In this study, we reported a case of nIHH patient and explored the pathogenic mechanism ofin nIHH. Avariant (c.2008G>A, p.E670K) and avariant (c.964G>A, p.D322N) were detected by the whole exome sequencing in this nIHH patient. Bioinformatic analysis revealed that thisvariant (c.2008G>A) causes structural perturbations in TK2 domain demonstrating that this variant result in FGFR1 loss-of-function and abnormal signaling. The identification of an additionalvariant (c.964G>A) indicated thatmight play a potential role in developmental abnormalities and inhibition of GnRH neuron release. A protein interaction network analysis showed that CEP290 was predicted to interact with FGFR1. In summary, our study identified the potential pathogenic mechanism(s) of the novelvariant and indicated thatmight play a role in the GnRH neuron migration route. Our findings expand the mutation spectrum ofandand provide a reference for clinical diagnosis and treatment of IHH.

IHH;;; bioinformatics analysis

2022-06-15;

2022-09-17;

2022-09-29

国家自然科学基金项目(编号:81974124)和泰山学者项目专项资金(编号:20161071)资助[Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81974124) and the Special Funds for the Taishan Scholar Project (No. 20161071)]

王姗姗,在读硕士研究生,专业方向:内分泌与代谢遗传学。E-mail: 593603071@qq.com

徐潮,博士,教授,主任医师,研究方向:性腺发育不良的精准诊疗。E-mail: doctorxuchao@163.com

10.16288/j.yczz.22-196

(责任编委: 周红文)