Siponimod exerts neuroprotective effects on the retina and higher visual pathway through neuronal S1PR1 in experimental glaucoma

Devaraj Basavarajappa, Vivek Gupta, Nitin Chitranshi, Roshana Vander Wall, Rashi Rajput, Kanishka Pushpitha,Samridhi Sharma, Mehdi Mirzaei, Alexander Klistorner, Stuart L.Graham

Abstract Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor (S1PR) signaling regulates diverse pathophysiological processes in the central nervous system.The role of S1PR signaling in neurodegenerative conditions is still largely unidentified.Siponimod is a specific modulator of S1P1 and S1P5 receptors, an immunosuppressant drug for managing secondary progressive multiple sclerosis.We investigated its neuroprotective properties in vivo on the retina and the brain in an optic nerve injury model induced by a chronic increase in intraocular pressure or acute N-methyl-D-aspartate excitotoxicity.Neuronal-specific deletion of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor (S1PR1) was carried out by expressing AAV-PHP.eB-Cre recombinase under Syn1 promoter in S1PR1flox/flox mice to define the role of S1PR1 in neurons.Inner retinal electrophysiological responses, along with histological and immunofluorescence analysis of the retina and optic nerve tissues,indicated significant neuroprotective effects of siponimod when administered orally via diet in chronic and acute optic nerve injury models.Further, siponimod treatment showed significant protection against trans-neuronal degenerative changes in the higher visual center of the brain induced by optic nerve injury.Siponimod treatment also reduced microglial activation and reactive gliosis along the visual pathway.Our results showed that siponimod markedly upregulated neuroprotective Akt and Erk1/2 activation in the retina and the brain.Neuronal-specific deletion of S1PR1 enhanced retinal and dorsolateral geniculate nucleus degenerative changes in a chronic optic nerve injury condition and attenuated protective effects of siponimod.In summary, our data demonstrated that S1PR1 signaling plays a vital role in the retinal ganglion cell and dorsolateral geniculate nucleus neuronal survival in experimental glaucoma, and siponimod exerts direct neuroprotective effects through S1PR1 in neurons in the central nervous system independent of its peripheral immuno-modulatory effects.Our findings suggest that neuronal S1PR1 is a neuroprotective therapeutic target and its modulation by siponimod has positive implications in glaucoma conditions.

Key Words: glaucoma; intraocular pressure; neurodegeneration; neuroprotection; optic nerve injury; retinal ganglion cells; siponimod; sphingosine-1-phosphate

Introduction

Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) is a crucial lipid signaling molecule generated from ceramide metabolism and binds to five G-protein-coupled receptors,termed S1P1-5 receptors (S1PR1-5) (O’Sullivan and Dev, 2017).S1PRs are expressed ubiquitously and play major roles in cell survival, growth, migration,and differentiation.Consequently, S1PR modulation has emerged as a potential therapeutic strategy in various diseases, including inflammatory,cardiovascular, and brain disorders (Cartier and Hla, 2019).Siponimod(BAF312) and fingolimod (FTY720) are S1P structural analogues that modulate S1P receptor signaling and are approved immunosuppressive drugs for the treatment of multiple sclerosis (MS) (Kappos et al., 2006, 2018; Gajofatto,2017).The active form, fingolimod-phosphate (fingolimod-P), formed followingin vivo

phosphorylation, binds potently to four S1P receptors, S1P1,S1P3, S1P4, and S1P5.Siponimod, in contrast, is a selective modulator of S1P1 and S1P5 receptors.Immunomodulation has been primarily regarded as the mechanism of action of both drugs in MS.Modulation of S1PR in lymphocytes by these drugs prevents their egress from secondary lymphoid organs and consequently infiltration into the CNS, reducing inflammation (Kappos et al.,2006; Chun et al., 2019).The CNS cells express four out of the five S1PRs (S1P1, S1P2, S1P3, and S1P5)(Healy and Antel, 2016), though the expression levels vary depending on the cell type and the injury stimulus (Healy and Antel, 2016; Karunakaran and van Echten-Deckert, 2017; Lucaciu et al., 2020).A growing body of evidence shows that S1PR signaling is implicated in the pathophysiology of various disorders of the CNS.S1PRs in neuronal precursor cells and neurons play roles in cell migration, neurogenesis, neural development, and survival (Gupta et al., 2012; Karunakaran and van Echten-Deckert, 2017).S1PR signaling pathways in microglia and astrocytes regulate their activation, proliferation,gliosis, and neuroinflammation (Lucaciu et al., 2020).S1PRs in oligodendroglia and oligodendrocyte precursor cells participate in differentiation, survival, and myelination (Martin and Sospedra, 2014; Roggeri et al., 2020).Siponimod,in addition to immunomodulatory effects on the peripheral immune cells,can cross the blood-brain barrier (Hunter et al., 2016; Kipp, 2020; Bigaud et al., 2021).Recent data on the protective effects of siponimod in clinical trialsinvolving secondary progressive MS patients suggests that siponimod may directly interact with S1PRs in the CNS (Behrangi et al., 2019; Dumitrescu et al., 2019) which is important as secondary progressive MS is largely driven by local CNS degenerative mechanisms (Baecher-Allan et al., 2018; Simkins et al.,2021).There is limited evidence to demonstrate thein vivo

role of S1PRs in the CNS cell types in degenerative conditions.The retina and optic nerve (ON) are considered unique extensions of the CNS and show specific changes in response to various neurological disorders (London et al., 2013).Glaucoma is an age-related multifactorial neurodegenerative disease, clinically characterized by cupping of the optic nerve head with irreversible visual field loss due to ON damage and retinal ganglion cell (RGC) death, with anterograde trans-neuronal degeneration in higher visual centers (Jonas et al., 2017; Mélik Parsadaniantz et al., 2020).The major risk factor for the development and progression of glaucoma is elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) (Pang and Clark, 2020).Elevated IOP causes axonal transport disruption, microvascular abnormalities, extracellular matrix remodeling, glial activation, and ultimately RGCs degeneration (You et al., 2013; Artero-Castro et al., 2020; Rolle et al., 2020).Based on the above discussion, we hypothesized that targeting neuronal S1PR1 by siponimod could produce neuroprotective effects in glaucoma conditions, independent of the drug’s peripheral immunosuppressive effects.The present study investigated the neuroprotective effect of siponimod on the visual pathway in glaucomatous conditions using combined physiological, structural, and biochemical measures.Further, we established the role of S1PR1 in RGCs survival, ON damage, and trans-neuronal degeneration in higher visual centers and the drug-mediated effects using cell-specific S1PR1 ablated mice.

Methods

Experimental animals

All animal experiments in this study were conducted in compliance with the Australian Code of Practice for the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes and the guidelines of the ARVO (the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology) Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and approved by Macquarie University Animal Ethics Committee (AEC Reference No.2018/018) approved on June 28, 2018.Wildtype C57BL/6 mice (4-6 weeks, body weight 16-20 g) were purchased from Animal Resources Centre, Perth, Australia.B6.129S6(FVB)-S1pr1/J mice (4-6 weeks, body weight 16-20 g, RRID: IMSR_JAX:019141) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA).Mice were bred under specific pathogen-free conditions at the Animal Care Facility of Macquarie University.All animals were maintained in an air-conditioned room with a controlled temperature (21-28°C) and fixed daily 12-hour light/dark cycles.The animals were randomly divided into four groups (10 mice in each group): (1) control (sham, normal IOP) group, (2) control (sham, normal IOP) group with siponimod treatment, (3) high IOP/NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartate) excitotoxicity subjected untreated group and (4) high IOP/NMDA excitotoxicity subjected group with siponimod treatment.Before assigning,we first examined 4-6 week-old mouse eyes for abnormality, including topical fluorescein assessment using ophthalmoscope/magnifying loupes.The initial baseline electrophysiological responses, electroretinogram (ERG),and positive scotopic threshold response (pSTR) were also measured to ensure the normal health status of the animal eyes.Siponimod (BAF312) was obtained from Novartis (Basel, Switzerland) and administered to recipient mice through a dose of 10 mg/kg incorporated in the diet and fedad libitum

,and 3-4 mice per cage were maintained.This dose was chosen based on previously optimized dose-dependent effects of siponimod in rodent models(Dietrich et al., 2018).Diet loaded with 10 mg/kg siponimod was suggested as an optimized dose for long-term preclinical studies to get maximum drug effects (approximately equivalent to a daily drug intake of 30 μg/mouse when considering a mean daily food uptake of ~3 g/d) (Bigaud et al., 2021).Induction of elevated IOP by intracameral microbead injections

Elevation of IOP was induced by injection of polystyrene microspheres (10-μm diameter FluoSpheres; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) into the anterior chamber of the eyes as described previously (You et al., 2014; Chitranshi et al., 2019; Abbasi et al., 2020, 2021).Briefly, mice were anesthetized with intraperitoneal injections of ketamine (75 mg/kg) (Provet Pty Ltd, Erskine Park, NSW, Australia) and medetomidine (0.5 mg/kg) (Troy Laboratories Pty Ltd, Glendenning, NSW, Australia) and the body temperature was maintained using a warming pad throughout the experimental procedure.After pupils were dilated with topical 1% tropicamide, topical anesthetic drops (Alcaineproxymetacaine 0.5%, Alcon Laboratories Pty Ltd, Macquarie Park, NSW,Australia) were applied prior to injections.Intracameral injections were performed with 2 μL of polystyrene microspheres (3.6 × 10microbeads/mL)using a Hamilton syringe connected to a disposable 33G needle (TSK Laboratory, Tochigi, Japan).All procedures were performed using an operating microscope (OPMI Vario S88, Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), and care was taken to avoid needle contact with the iris or lens.One of the eyes was randomly selected for ocular injection, leaving the other eye as contralateral intra-animal control.An equivalent volume of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was injected into the eyes of control (sham) mice, and these animals served as the control group (normal IOP).Anesthesia was reversed by subcutaneous atipamezole (0.75 mg/kg) injection and 0.3% ciprofloxacin drops (Ciloxan; Alcon Laboratories Pty Ltd) and 0.1% dexamethasone eye drops (Maxidex, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Australia Pty Ltd, Macquarie Park,NSW, Australia) were applied to the injected eyes.Lacrilube (Allergan Australia Pty Ltd, Gordon, NSW, Australia) was then applied to the cornea.Microbead injection was performed weekly between weeks 0 and 4 and then fortnightly until week 8.The IOP was monitored regularly using an iCare TonoLab rebound tonometer (Icare Tonovet, Helsinki, Finland) as described previously(Chitranshi et al., 2019; Abbasi et al., 2020; Mirzaei et al., 2020).

Electroretinographic analysis

Scotopic electroretinographic recordings were performed as described previously using the Ganzfeld ERG system (Phoenix Research Laboratories,Pleasanton, CA, USA) (Joly et al., 2017; Rodriguez et al., 2018).Mice were dark-adapted overnight and anesthetized with ketamine and medetomidine(75 and 0.5 mg/kg, respectively) and placed on a warming pad.Pupils were dilated using 1% tropicamide, and topical anesthetic (Alcaine, Alcon Laboratories Pty Ltd) drops were applied to the cornea under dim red light.The ground and reference electrodes were inserted into the tail and subcutaneously into the forehead of the animal, respectively.The body temperature of the animals was maintained at around 37°C with an electric heating pad during recordings.The recording electrode (gold-plate objective lens) was placed on the eye’s corneal surface after applying hypromellose to maintain proper contact between the cornea and the electrode to record ERGs.After stabilizing the baseline in darkness, the ERG responses were recorded from each eye individually.ERGs were recorded using a flash intensity of 6.1 log cd·s/m.Dim stimulation (-4.3 log cd·s/m) was delivered 30 times at a frequency of 0.5 Hz.The amplitude of positive scotopic threshold response (pSTR) was measured from baseline to the positive peak observed around 120 ms.

Intravitreal NMDA injection

Retinal neurotoxicity was induced by a single intravitreal injection of NMDA (30 nmol per eye) (Dheer et al., 2019).Mice were anesthetized in an induction chamber with 2-5% isoflurane in oxygen, and then animals were maintained on 1-3% isoflurane in oxygen (0.6-1 L/min flow of oxygen) on a warming pad during the procedure.After pupils were dilated with 1% tropicamide, a single amount of 3 μL NMDA (Sigma-Aldrich, St.Louis, MO, USA) solution in sterile PBS was administered using a 33G needle into the vitreous chamber behind the lens.The control animal group eyes were injected with an equivalent volume of sterile PBS.All injections were performed under an operating surgical microscope (OPMI Vario S88, Carl Zeiss).At 7 days after NMDA injection, inner retinal electrophysiological recordings were performed by measuring pSTR responses, and animals were sacrificed by cervical dislocation to harvest the tissues for analysis.

Viral injections

Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs), stereotype AAV-PHP.eB (Vector Biolabs, USA)harboring Cre recombinase under neuron-specific promoter hSyn1 (AAV-PHP.eB-Syn1-GFP-Cre and AAV-PHP.eB-Syn1-GFP as control) or oligodendrocyte specific promoter, MBP (myelin basic protein) (AAV-PHP.eB-MBP-GFP-Cre and AAV-PHP.eB-MBP-GFP as control) were systemically delivered through tail vein injection into S1PR1transgenic mice 1 week before inducing elevated IOPs.Adult mice of 4-5 weeks old were anesthetized and maintained in 1-3%isoflurane in oxygen on a warming pad as stated above during viral injections.Mice were injected with 50 μL AAV viral suspension (1.5 × 10vg) manually into a lateral tail vein using a 33G needle attached to the Hamilton syringe.Tails were warmed before injection in 40°C water for 1 minute and cleaned with 70% alcohol pads, prior to viral vector delivery.Immunofluorescence staining

Mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation, and the brain, eyes, and ONtissues were harvested from the animals after transcardial perfusion with PBS and 4% paraformaldehyde.Postfixed tissues were then embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT) (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA, USA) in dry ice.ON were dissected approximately 1 mm anterior to the optic nerve head and embedded vertically in OCT.Seven-micrometer thick sagittal retinal cryosections were cut for eyes, 3-μm thick cross-sections were cut for optic nerves, and 15-μm thick serial coronal sections were cut for brains using Leica CM1950 cryo section equipment (Leica Biosystems, Nussloch, Germany).The coronal plane sections between -2.05 to -2.20 mm from Bregma were used for staining (Bertacchi et al., 2019; You et al., 2019).Cryosections or deparaffined sections (after antigen retrieval) were treated with a blocking buffer containing 0.3% Triton X-100 and 5% serum of the secondary species(donkey) (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS for 2 hours at room temperature.The tissue sections were then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C.The following primary antibodies were used for immunofluorescence staining: rabbit anti-Iba1 (Ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1)(microglial marker; 1:1500; 019-19741, FUJIFILM Wako Shibayagi, Cat# 019-19741, RRID: AB_839504); rabbit anti-GFAP (glial fibrillary acidic protein)(a marker for reactive gliosis; 1:1500; Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA, Cat#Z0334, RRID:AB_10013382), rabbit anti-GFP (green fluoresce protein) (a reporter marker; 1:500; Abcam, Vic, Australia, Cat# ab290, RRID: AB_303395)and mouse anti-NeuN (neuronal marker; 1:1000; Abcam, Cat# ab104224,RRID: AB_10711040) and mouse anti-phosphorylated neurofilament heavychain (pNFH) (optic nerve damage marker; 1:1000; BioLegend-SMI-31, San Diego, CA, USA, BioLegend, Cat# 801601, RRID: AB_2564641).After primary antibody incubation, the sections were washed with PBS four times and incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies with a dilution of 1:500 at room temperature for 1 hour (Cy3-AffiniPure donkey anti-rabbit IgG (H+L),Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs, West Grove, PA, USA, Cat# 711-165-152,RRID: AB_2307443 or Alexa Fluor 488-AffiniPure donkey anti-mouse IgG(H+L), Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs, Cat# 715-545-150, RRID: AB_2340846),washed and mounted with anti-fade mounting media with Prolong 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Life Technologies, Eugene, OR, USA).All images were acquired using a Zeiss fluorescence microscope (ZEISS Axio Imager Z2, Carl Zeiss).The pNFHarea and glial activation were measured from the immunofluorescence images of three-four cross-sections of each animal’s optic nerve using ImageJ software (version 1.52; NIH, Bethesda, MD,USA; Schneider et al., 2012).Three to four sections of medial dorsolateral geniculate nucleus (dLGN) from each animal brain were chosen for imaging and quantification of NeuN-positive cells in dLGN using ImageJ software.

Histology

Post-fixed eye and brain tissues were processed via an automatic tissue processor (Leica ASP200S, Leica Biosystems) and embedded in paraffin wax.Tissue marking dye was used to ensure identical eye orientation.Paraffin sections (7-μm thick) of retinal specimens comprised the whole retina cut through the optic nerve head (parasagittal plane containing the superior and the inferior retina within the width of the ON) and were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H and E).Images were captured using Zeiss Microscope (ZEISS Axio Imager Z2) and analyzed with ImageJ.The number of cells in the ganglion cell layer (GCL) was counted over a length of 500 μm (100 to 600 μm from the edge of the optic disc).Cell counts were obtained from three consecutive sections of each animal eye and averaged to analyze the number of cells in the GCL.For brain tissue, serial coronal paraffin sections(10 μm thick) comprising medial dLGN sections (between -2.05 to -2.20 mm from Bregma) from each animal brain were chosen for Nissl blue staining.Briefly, the deparaffined brain sections were hydrated with ethanol gradient and stained with cresyl violet (0.5%) for 5 minutes, and rinsed with water before mounting.Stained sections were imaged using Zeiss Microscope (ZEISS Axio Imager Z2, Carl Zeiss) and the viable Nissl positive neurons with visible nuclei were counted using ImageJ.Neuron densities were measured from three to four consecutive sections of each animal in the dLGN region of the brain.

Western blot analysis

Harvested tissue samples were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and subsequently resuspended in ice-cold lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0,1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM PMSF, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM NaVO, 0.1%SDS and complete protease inhibitor cocktail).Tissue samples (retina and microdissected dLGN of the brain) were then homogenized by sonication and centrifuged at 10,000 ×g

for 10 minutes at 4°C to collect the protein supernatant.The protein concentration of the lysates was quantified by Micro BCA assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).Proteins(around 20 μg) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane by electroblotting (Invitrogen iBlot2, Thermo Fisher Scientific).Membranes were blocked with non-fat dry milk powder (5%) in TTBS (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 hour at room temperature and incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C.The primary antibodies used were: rabbit monoclonal anti-phospho-Akt (Ser473)(1:1000; (D9E) XP 4060, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA, Cat#4060, RRID: AB_2315049), rabbit monoclonal anti-Akt (1:1000; 11E7 (pan),Cell Signaling Technology, Cat# 4685, RRID: AB_2225340), rabbit monoclonal anti-phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (Thr202/Tyr204) (1:1000; (20G11), Cell Signaling Technology, Cat# 4376, RRID: AB_331772), and rabbit monoclonal anti-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (1:1000; (137F5), Cell Signaling Technology,Cat# 4695, RRID: AB_390779); rabbit polyclonal anti-GFP (1:1000; Abcam,Cat# ab290, RRID: AB_303395), rabbit polyclonal anti-S1P1/EDG1 (1:1000;Abcam, Cat# ab11424, RRID: AB_298029) and mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin(1:5000; Abcam, Cat# ab6276, RRID: AB_2223210); rabbit polyclonal anti-Iba1 (1:1000; FUJIFILM Wako Shibayagi, Cat# 019-19741, RRID: AB_839504);rabbit polyclonal anti-GFAP (1:1500; Agilent, Z0334, RRID: AB_10013382).The membranes were then washed and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with a secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (goat anti-rabbit 1:5000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 31460, RRID: AB_228341 and goat anti-mouse 1:5000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 62-6520, RRID:AB_2533947).After washing, the protein bands were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Super Signal West Femto Maximum Sensitive Substrate;Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and images were captured with a Bio-Rad ChemiDocImaging system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA).The mean densitometry analysis of band intensities was determined after relative expression of the proteins normalized to β-actin using ImageJ software.Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the data in this study was performed as described previously (Chitranshi et al., 2019; Abbasi et al., 2020) using GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA, www.graphpad.com).The animals subjected to four experimental groups were utilized to analyze the retinal electrophysiological (pSTR amplitudes) changes, optic nerve damage, histology, western blotting, and immunofluorescence staining of the tissues.The number of samples (n

) indicated in each figure represents thetissues from the different animals of the same group.Comparisons between the groups were performed by one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.All the data are presented as mean ±standard deviation of the mean (SD) for givenn

sizes.AP

-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for data analysis.Results

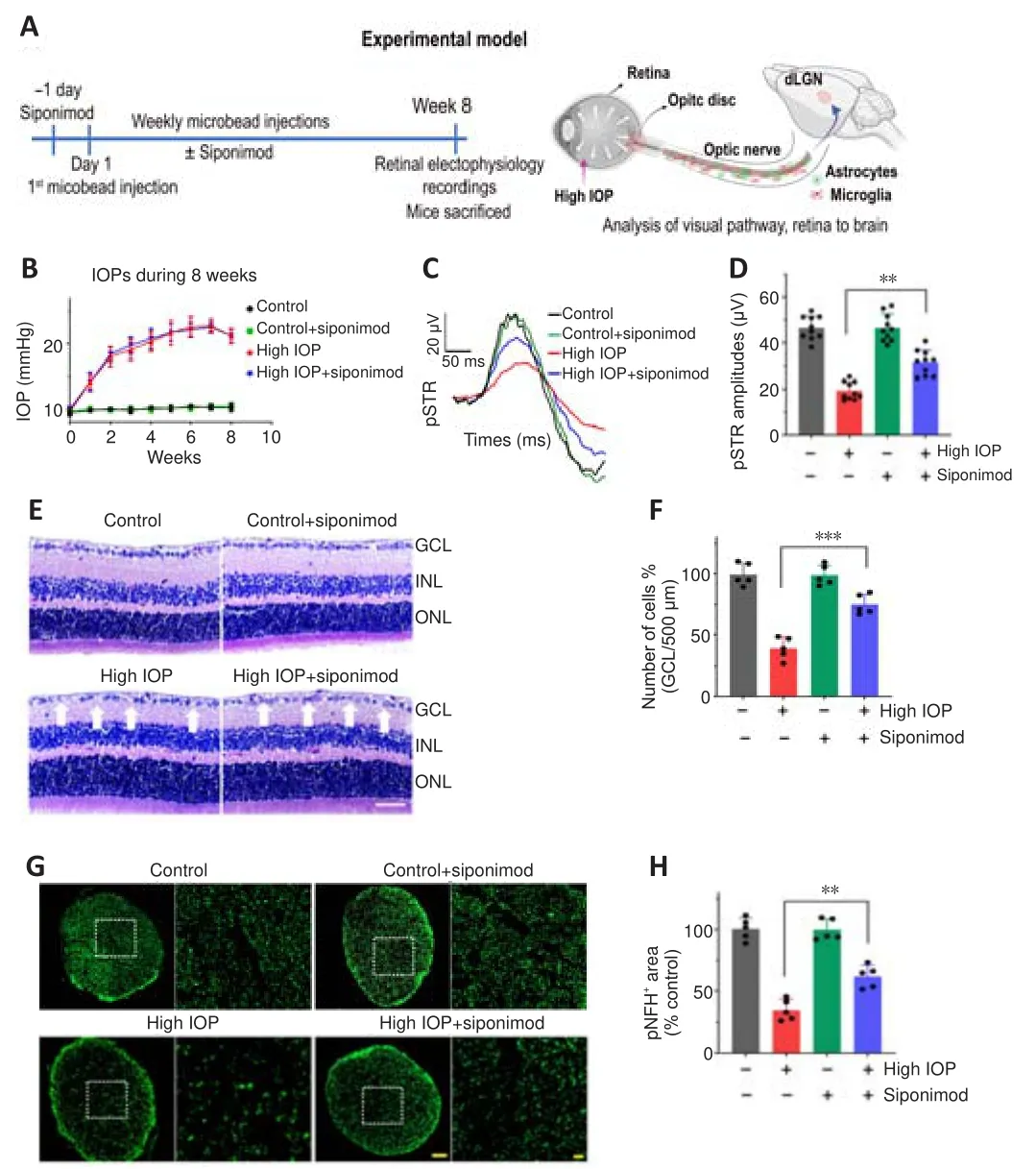

Siponimod preserves retinal structure and function in optic nerve injury models

The potential protective effects of siponimod on inner retinal function and structure were measured in a high IOP mouse model (Figure 1A).For functional assessment of the inner retina, we measured the pSTR amplitudes(You et al., 2013).Siponimod-treated mice with intracameral injections of microbeads showed elevated IOPs comparable to the untreated control animals (Figure 1B).After 8 weeks, the high IOP subjected eyes exhibited a decline in pSTR amplitudes, while mice treated with siponimod (10 mg/kg in the diet and fedad libitum

) showed significant protection against the pSTR amplitude loss (P

< 0.01; Figure 1C and D).Assessment of cellular changes in the ganglion cell layer (GCL) and ON damage was then performed.Histological analysis of the retinal sections stained with H and E revealed a significant decrease in the number of cells in GCL in high IOP subjected untreated mice eyes compared with the control normal IOP (sham) mice eyes (P

< 0.001).GCL loss was significantly attenuated in the siponimod-treated mice group compared with the untreated mice group in high IOP conditions, where GCL cell density loss decreased from 60.64 ± 8.73% to 25.29 ± 8.21% (P

< 0.001; Figure 1E and F).Neurofilament heavy chain in RGC axons has been reported to undergo dephosphorylation in eyes subjected to elevated IOP (Kashiwagi et al., 2003; Chidlow et al., 2011).Immunofluorescence staining of ON cross-sections with phosphorylated neurofilament heavy chain (pNFH) antibody and pNFHarea measurements revealed a significant decrease in pNFH immunoreactivity in high IOP ONs.This ON axonal damage in elevated IOP conditions was decreased from 64.88 ± 8.25% to 38.21 ± 9.15% with siponimod treatment compared with the untreated mice (P

< 0.01; Figure 1G and H).These results indicated that siponimod exerts neuroprotective effects on the retina and ON against neurodegenerative changes induced by chronic high IOP.The neuroprotective effect of siponimod on the retina was further tested in an acute NMDA excitotoxicity model.A significant retinal functional deterioration in response to NMDA toxicity was observed after 7 days postinjury.The pSTR amplitudes in NMDA-treated mice were reduced by 65.33± 3.78%, and this reduction was significantly protected with siponimod treatment (P

< 0.05; Figure 2A and B).H and E staining of retinal sections and examination of ONs stained with pNFH further revealed the protective effects of siponimod.NMDA-induced cell loss in GCL decreased from 71.36 ±9.61% to 47.58 ± 11.50% in the siponimod treated group compared with the untreated mice group (P

< 0.05; Figure 2C and D).Axonal damage assessed by pNFHarea measurements showed pNFH immunoreactivity loss was decreased from 51.39 ± 10.99% to 22.02 ± 10.74% in siponimod treated mice in NMDA excitotoxicity condition compared with the untreated mice group(P

< 0.05; Figure 2E and F).These results emphasize the protective effects of siponimod treatment on the retina in the NMDA injury model.

Figure 1 | Neuroprotective effects of siponimod on function and structure of the retina and optic nerve (ON) in high intraocular pressure (IOP) condition.

Figure 2 | Neuroprotective effects of siponimod on function and structure of the retina and optic nerve (ON) against acute retinal N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)excitotoxicity.

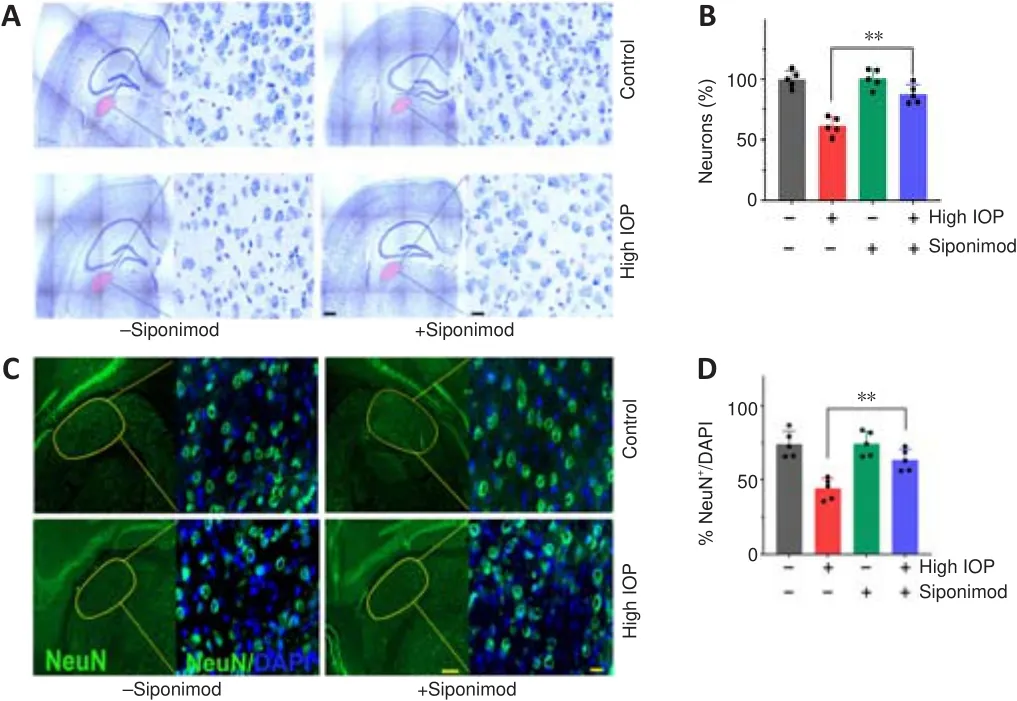

Protective effects of siponimod on trans-neuronal degenerative changes in dLGN

Neuronal degenerative changes in the dLGN have been documented in ON injury conditions (Gupta et al., 2007; Yücel and Gupta, 2008; Sriram et al.,2012).The effect of siponimod on trans-neuronal degeneration under chronic elevated IOP in the dLGN region of the brain was evaluated by staining coronal brain sections with Nissl blue and NeuN.Quantitative neuronal cell density analysis revealed a significant protective effect of siponimod on neuronal cell loss in the dLGN.A decline of 38.95 ± 7.26% in neuronal cell density was observed in high IOP mice, and this degeneration was reduced to 12.53 ± 7.85% (P

< 0.01) in the siponimod treated group compared with the untreated mice group (Figure 3A and B).Further, in high IOP eyes, the frequency of NeuNcells was decreased by 39.34 ± 6.77%, whereas this loss was reduced to only 13.72 ± 7.36% in the siponimod treated group (Figure 3C and D).The higher visual cortex (V1) analysis in this high IOP condition for 2 months period showed no significant trans-neuronal degenerative changes.These results together establish a significant protective effect of siponimod on the neuronal cell population in the dLGN region of the brain.Siponimod upregulates pro-survival signaling pathways

Phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K)/Akt and the mitogen-activated protein kinase (Erk1/2) signaling play a critical role in neuron survival (Rai et al.,2019; Xu et al., 2020).FTY720 treatment has been shown to promote Akt/Erk activation in cultured neuronal cells andin vivo

conditions (Zhang and Wang,2020).Akt and Erk1/2 phosphorylation levels were evaluated by western blotting.A decrease in Akt and Erk phosphorylation levels was observed under high IOP conditions in the retina and dLGN region of the brain.Mice treated with siponimod showed significantly enhanced Akt (P

< 0.01) and Erk1/2 phosphorylation in the retina (P

< 0.01) and the dLGN (P

< 0.01 for Erk1;P

<0.001 for Erk2; Figure 4A and B) compared with the untreated mice group in high IOP conditions.

Figure 3 | Protective effects of siponimod on the dorsolateral geniculate nucleus(dLGN) of the brain in chronic glaucoma condition (8 weeks).

Figure 4| Siponimod upregulates Akt and Erk1/2 phosphorylation in the retina and the brain.

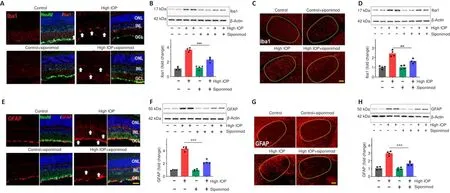

Siponimod reduces microglial activation and reactive gliosis in the glaucoma model

Chronic neuroinflammation in glaucoma is implicated as an important component in disease pathogenesis.The early reactivity of glial cells(microglial activation and reactive gliosis) has been observed in the retina(Mélik Parsadaniantz et al., 2020; Rolle et al., 2020).Glial activation along the visual pathway was evaluated by investigating Iba1 and GFAP expression alterations.Immunofluorescence staining of the retina, ON, and the brain tissue sections with Iba1 and GFAP revealed activation of glial cells along the visual pathway in chronic high IOP condition (Figure 5 and Additional Figure 1).Activated microglia in the retina, ON, and dLGN were reduced with siponimod treatment in chronic high IOP conditions (Figure 5A, C andAdditional Figure 1A).Microglial activation in the ON evaluated by measuring changes in Iba1areas indicated a significant increase (3.02 ± 0.29-fold) of Iba1 immunoreactivity in the high IOP model.This activation was reduced in the siponimod-treated group to 1.84 ± 0.41 fold (Additional Figure 1A).Western blot analysis of retinal and dLGN tissues for Iba1 expression revealed a 3.63 ± 0.25-fold increase in the retina and 2.43 ± 0.32-fold increase in dLGN in high IOP conditions, and this upregulation was significantly diminished with siponimod treatment (2.27 ± 0.31-fold in retina and 1.63 ± 0.22-fold in dLGN)(Figure 5B and D).

In control retinas, GFAP immunoreactivity was primarily confined to the GCL.High IOP retinas showed GFAP labeling as a dense network of Müller cell processes in the GCL along with the emergence of a radial pattern of GFAP immunopositivity (Figure 5E).Similar hypertrophic reactive astrogliosis with upregulated GFAP was observed in ON (Additional Figure 1B) and dLGN of high IOP subjected mice (Figure 5G).This reactive gliosis was diminished with siponimod treatment.Western blot quantitative analysis of GFAP expression in the retina and dLGN tissues showed 4.33 ± 0.35-fold and 2.96 ± 0.27-fold upregulation, respectively in high IOP conditions compared with the control normal IOP (sham) mice group.Siponimod treatment resulted in its suppression to 2.23 ± 0.31-fold in the retina and 1.65 ± 0.23-fold in dLGN compared with the untreated mice (Figure 5F and H).GFAP immunoreactivity in the ON was increased to 3.47 ± 0.5-fold in high IOP condition compared with the control normal IOP (sham) mice but was reduced significantly to 1.96± 0.30 fold in siponimod treated mice (P

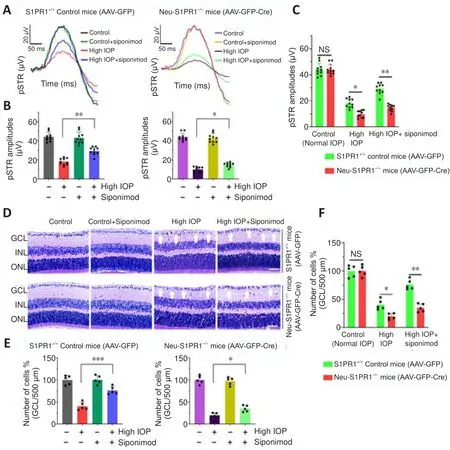

< 0.001; Additional Figure 1B).These results indicated that the siponimod treatment effectively reduced microglial activation and reactive gliosis in chronic high IOP experimental glaucoma.S1PR1 loss in RGCs and neurons exacerbates glaucoma injury attenuating siponimod protective effects

To define the role of S1PR1 intrinsic signaling in neuronal survival and its involvement in mediating the protective effects of the drug in glaucoma conditions, neuronal-specific ablation of S1PR1 was carried out in S1PR1mice.The Cre-recombinase under neuron-specific promoter, Syn1 was integrated into AAV-PHP.eB vector and viral vectors were administered intravenously to S1PR1mice (Additional Figure 2A).Efficient delivery of AAV construct crossing the blood-brain barrier was evident by GFP expression in the neuronal cells of mice receiving AAV injections.The transduction efficiency measured by the ratio of GFPcells to the total NeuNcells achieved 83.20 ± 7.63% for GFP control and 82.36 ± 6.87 for Cre recombinase AAVs in the dLGN regions of the brain.Similarly, the transduction efficiency of 76.93 ± 4.73% for GFP control and 75.31 ± 5.53%for Cre AAVs was observed for RGCs in the retina (Additional Figure 2B-D).Western blot analysis of dLGN and retinal tissues further validated the loss of S1PR1 expression in AAV-Cre recombinase-expressing mice.Densitometric quantification demonstrated that the S1PR1 expression in AAV-GFP-Cre injected mice was decreased by 67.95 ± 7.15% in the dLGN and about 61.43± 7.79% in the retina compared with the AAV-GFP injected control mice (P

<0.0001; Additional Figure 2E and F).The mice injected with AAV-GFP referred to as S1PR1control mice (AAVGFP) and the neuron-specific S1PR1 deleted mice (termed as Neu-S1PRmice (AAV-GFP-Cre)) were administered siponimod diet (Additional Figure 3).No significant functional or structural changes were observed in the retina upon neuronal S1PR1 ablation under normal conditions.However,upon microbead-induced ON injury, neuronal S1PR1 ablated mice showed a significant decrease in the pSTR amplitudes and GCL thinning.Interestingly,the protective effects of siponimod were significantly attenuated in the group subjected to neuronal S1PR1 impairment (Neu-S1PR, AAV-GFP-Cre)compared with control S1PRanimals (AAV-GFP).High IOP-induced pSTR amplitude loss of 57.69 ± 5.03% was reduced to 32.58 ± 4.57% in siponimodtreated S1PRcontrol animals.However, NeuN-S1PR1animals exhibited 77.62 ± 2.74% loss in high IOP eyes compared with 66.43 ± 2.45% loss in the siponimod treated group (P

< 0.01; Figure 6A-C).Further, quantitative analysis of the GCL from H and E stained retinal sections revealed a significant decrease (P

< 0.05) in GCL density in Neu-S1PR1ablated (AAV-GFP-Cre) mice compared with S1PR1control (AAVGFP) mice in high IOP conditions.The siponimod-mediated protective effect was significantly diminished in Neu-S1PR1ablated mice compared with control S1PR1animals (P

< 0.01; Figure 6D-F).ON damage was assessed by performing pNFH immunoreactivity measurements that showed similar changes between Neu-S1PR1ablated mice and S1PR1control mice.However, the siponimod-treated group showed significantly greater immunoreactivity of pNFH only in S1PR1control mice compared with Neu-S1PR1mice (P

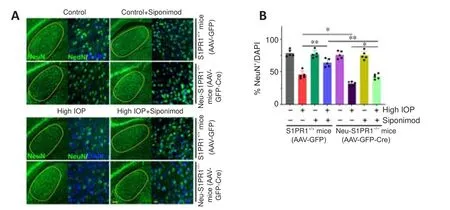

< 0.01; Additional Figure 4).We next analyzed the impact of neuronal S1PR1 ablation on degenerative changes in dLGN of the brain.A significant decline in the frequency of NeuNcells was observed in neuronal S1PR1 ablated mice (AAV-GFP-Cre)compared with control S1PR1(AAV-GFP) mice in high IOP conditions (P

< 0.05).No significant changes in dLGN neuronal cell density were evident in animals subjected to neuronal S1PR1 ablation under normal conditions.Neuronal S1PR1 ablation significantly reduced the protective effects of siponimod on the dLGN degenerative changes.Siponimod treatment showed a significantly greater frequency of NeuNcells in S1PRcontrol animals compared with Neu-S1PR1mice (P

< 0.01) in high IOP conditions (Figure 7).Quantitative histological analysis of the neuronal cell density showed a significantly reduced neuronal density (P

< 0.01) in the dLGN region in Neu-S1PR1ablated mice compared with the control S1PR1animals in high IOP conditions.The protective effect of siponimod on the dLGN neuronal density observed in the control S1PR1mice was significantly diminished in the Neu-S1PR1ablated group under high IOP conditions (P

< 0.01; Additional Figure 5).These results indicated that expression of S1PR1 in the neurons plays a pivotal role in cell survival in the retina and dLGN in high IOP-induced degeneration and that the protective effects of siponimod on the neurons under such conditions are mediated through neuronal S1PR1 expression.

Figure 5 | Siponimod treatment reduces glial activation along the visual pathway in chronic optic nerve injury condition (8 weeks).

Figure 6 | The functional importance of S1PR1 in neurons and its deletion impairs the protective effect of siponimod on inner retinal function and structure in chronic optic nerve injury condition.

Figure 7 | Neuron-specific deletion of S1PR1 reduced the protective effect of siponimod against trans-neuronal degeneration in dLGN of the brain in chronic optic nerve injury condition.

The effect of S1PR1 deletion in neurons on pro-surviving Akt and Erk1/2 pathways was evaluated by Western blot analysis.Mice treated with siponimod showed enhanced Akt and Erk1/2 phosphorylation levels in the retina and dLGN in S1PRcontrol animals (AAV-GFP) in high IOP conditions.S1PR1 ablation in neurons diminished siponimod-induced upregulation of Akt and Erk1/2 phosphorylation.The Neu-S1PR1(AAV-GFP-Cre) mice exhibited significantly decreased Akt and Erk1/2 phosphorylation levels with siponimod treatment both in the retina and dLGN (P

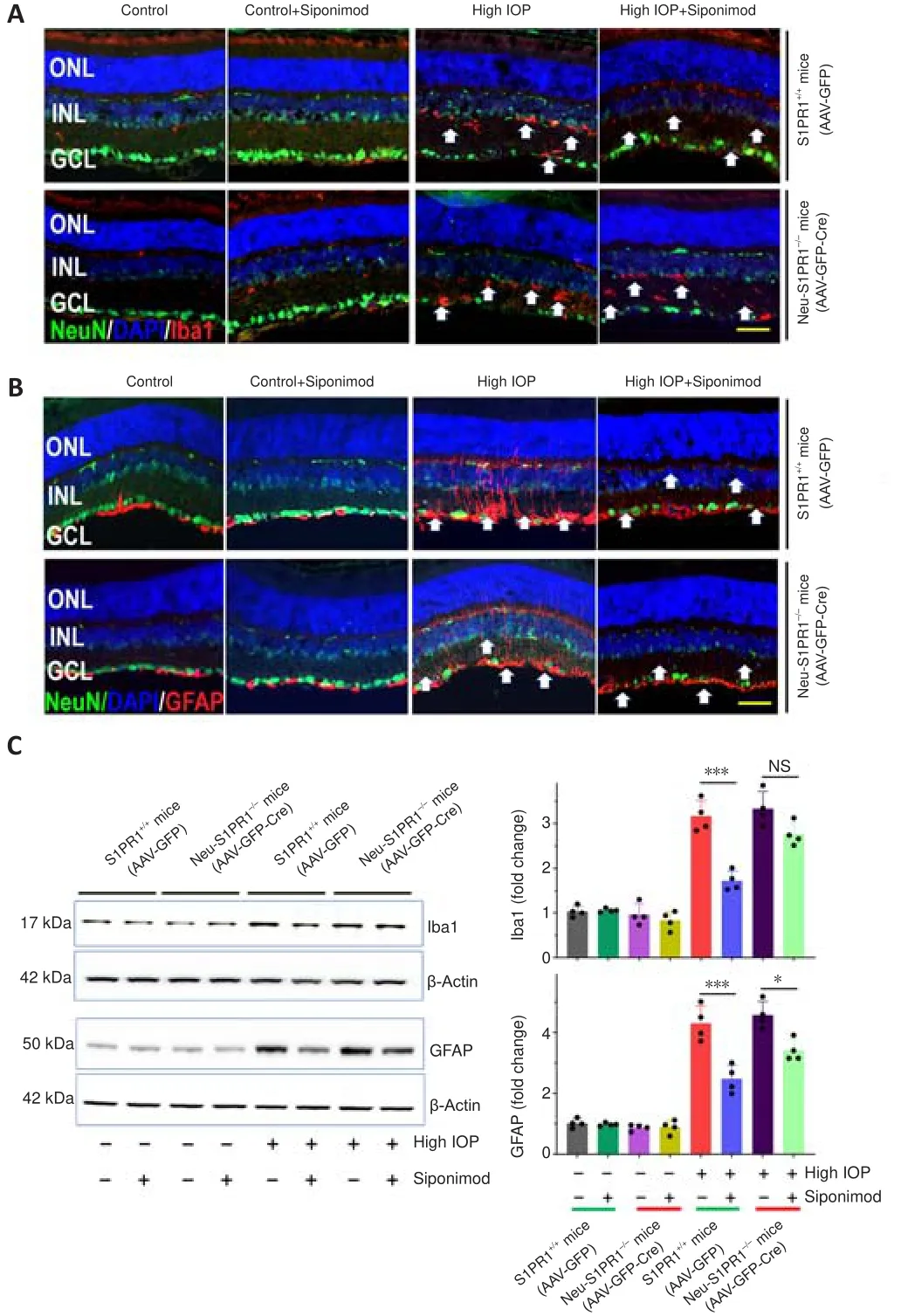

< 0.01) in high IOP conditions(Additional Figure 6).These results demonstrated that siponimod induces phosphorylation of Akt and Erk1/2 through S1PR1 signaling in neurons.Protective effects of siponimod on glial activation are attenuated in response to neuronal-specific S1PR1 ablation

We then determined whether the increased degeneration observed in Neu-S1PR1(AAV-GFP-Cre) mice with high IOP might impact siponimod-induced effects on glial activation.Similar to the results described in Figure 5 and Additional Figure 1, hypertrophic activated microglia and reactive gliosis analyzed with Iba1 and GFAP antibodies along the visual pathway were observed in untreated control S1PR1(AAV-GFP) mice in chronic high IOP conditions and this was reduced with siponimod treatment (P

< 0.001; Figure 8 and Additional Figures 7 and 8).Western blot quantification revealed a 3.16 ± 0.35-fold increase in Iba1 and 4.30 ± 0.57-fold upregulation of GFAP expression in the retina (P

< 0.001) in high IOP conditions compared with the control normal IOP (sham) mice group (Figure 8C).Similarly, in the dLGN 2.57 ± 0.28-fold increase for Iba1 and 3.17 ± 0.22-fold increase for GFAP expression were observed with chronic high IOP (P

< 0.001; Additional Figure 7C).This glial activation was reduced significantly to 1.52 ± 0.18 (dLGN)to 1.69 ± 0.21-fold (retina) for microglia and 2.13 ± 0.27 (dLGN)- to 2.47 ±0.37-fold (retina) for reactive gliosis with siponimod treatment in S1PR1control mice.This protective effect of siponimod on microglial activation was abolished in Neu-S1PR1mice.However, siponimod treatment showed a significant suppressive effect on reactive gliosis in Neu-S1PR1mice(AAV-GFP-Cre).Siponimod treatment significantly (P

< 0.05) reduced GFAP expression from 4.57 ± 0.44 to 3.41 ± 0.35-fold in the retina and 3.72 ± 0.32 to 2.88 ± 0.22-fold in dLGN of the brain in Neu-S1PR1mice under high IOP conditions compared with the untreated mice group.Further, similar levels of effects were observed in ONs evaluated by immunoreactivity of Iba1 and GFAP (Additional Figure 8).These results together suggest that a diminished protective effect of siponimod on glia was associated with enhanced degeneration after S1PR1 deletion in neurons.

Figure 8 | Attenuation of the protective effect of siponimod on retinal microglial activation and reactive Müller glia in high IOP condition in Neu-S1PR1-/- (AAV-GFP-Cre)mice.

The protective effects of siponimod are not primarily mediated through S1PR1 expression in oligodendrocytes

Death of oligodendrocytes in elevated IOP conditions has been reported along with axonal loss and RGC degeneration (Nakazawa et al., 2006; Son et al., 2010).Oligodendrocyte-specific S1PR1 deletion in S1PR1transgenic mice was achieved using AAV-PHP.eB vector expressing Cre recombinase enzyme under MBP promoter (Additional Figure 9A).Successful transduction of the CNS was evaluated by GFP expression on brain sections of the mice injected with AAVs.Immunofluorescence co-staining of the brain sections with GFP and oligodendrocytes specific marker MBP revealed the localization of GFP signal with MBP expression (Additional Figure 9B and C), indicating AAVs’ transduction in oligodendrocytes.Transduction efficiency assessed by measurement of GFParea to total MBP revealed 77.56 ± 5.53% for GFP control and 76.56 ± 5.43% Cre recombinase AAVs in dLGN of the brain(Additional Figure 9D).Western blot analysis of brain tissue (dLGN) revealed GFP expression in mice injected with AAVs.Densitometric quantification demonstrated the S1PR1 expression was decreased by 32.68 ± 6.57% in the brain in AAV-Cre injected mice (Additional Figure 9E and F).Then she spoke: Wind, wind, gently swayBlow Curdken s hat awayLet him chase o er field and woldTill my locks of ruddy goldNow astray and hanging downBe combed and plaited in a crown

The control S1PR(AAV-GFP) mice and oligodendrocyte-specific S1PR1(Oligo-S1PR1, AAV-GFP-Cre) mice eyes experienced similar levels of IOP increase (20-23 mmHg) (Additional Figure 10).Deletion of S1PR1 in oligodendrocytes did not display any significant effects on retinal structure and function of the retina in ON injury conditions.Similar levels of pSTR amplitude losses were observed between control and Oligo-S1PR1(AAVGFP-Cre) mice groups (18.67 ± 5.93 μVvs

.17.89 ± 4.76 μV) in high IOP conditions compared with the control normal IOP (sham) mice (P

< 0.001;Additional Figure 11A and B).Further, deletion of S1PR1 in oligodendrocytes did not change the protective effects of siponimod, with a similar level of protection of 63.63 ± 4.93% and 60.29 ± 5.59% against pSTR amplitudes loss was observed in control and Oligo-S1PR1(AAV-GFP-Cre) mice groups,respectively, compared with the untreated mice group (P

< 0.01).Cell counts in the GCL further supported the above effects and showed a similar extent of cell losses (60.23 ± 10.18%vs

.61.15 ± 10.9%).Siponimod treatment showed no significant differences in the protection conferred by drug treatment in both control and Oligo-S1PR1mice groups (GCL density: 77.8 ± 9.2%vs

.74.22 ± 10.11%) in glaucomatous injury compared with the untreated mice group (P

< 0.001; Additional Figure 11C and D).The extent of ON damage as assessed by pNFH immunofluorescence staining revealed similar levels of decrease in pNFH immunoreactivity between Oligo-S1PR1ablated mice (AV-GFP-Cre) and S1PR1(AAV-GFP) control mice (66.53 ± 9.85%vs.

66.0 ± 9.01%) in high IOP conditions compared with the control normal IOP (sham) mice (P

< 0.001).Siponimod treatment also showed similar levels of protective effect between control and Oligo-S1PR1mice groups in ON injury (63.86 ± 8.02%vs

.63.93 ± 8.84%) compared with the untreated mice group (P

< 0.01; Additional Figure 12A and B).Further,the ablation of S1PR1 in oligodendrocytes did not impact the degenerative changes in the dLGN.NeuNcell density in dLGN did not change significantly in Oglio-S1PR1ablated mice compared with control S1PR1mice (39.17± 6.10%vs.

42.8 ± 7.26%) in elevated IOP compared with the normal IOP conditions (P

< 0.01).Similarly, siponimod treatment did not exhibit any significant differences in the degenerative changes in the dLGN (Additional Figure 12C and D).These results suggest that high IOP-induced degenerative changes in the dLGN were not primarily mediated through S1PR1 expression in oligodendrocytes and that the protective effects of siponimod are not mediated through oligodendrocyte-specific S1PR1 expression.Discussion

This study demonstrates that siponimod treatment protects the retina and higher visual pathway in the ON injury model.We further examined the impact of S1PR1 deletion in neurons and oligodendrocytes using cellspecific conditional S1PR1 ablated mice.Siponimod treatment was recently demonstrated to reduce disability progression in a clinical trial involving secondary progressive MS patients (Gajofatto, 2017; Dumitrescu et al., 2019).This suggested that siponimod might have neuroprotective potential as the progressive form of MS is a chronic condition mainly driven by local CNS degenerative mechanisms (Frohman et al., 2005; Baecher-Allan et al., 2018).In this study, our results revealed that siponimod mediates neuroprotective effects on the retina and dLGN of the brain through neuronal S1PR1 in ON injury conditions and is independent of peripheral immunomodulatory effects.

S1PR1 modulation by S1P or FTY720 has been associated with mitogenic and pro-survival actions in neuronsin vivo

andin vitro

through activation of Akt and Erk pathways (Ye et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2017; Motyl et al., 2018).We observed reduced Akt and Erk 1/2 phosphorylation levels in the retina and dLGN in glaucomatous injury conditions, and these pathways were upregulated following siponimod administration.Further, we identified that deletion of S1PR1 in neurons reduced the siponimod-induced activation of Akt and Erk 1/2.These results suggest that neuroprotective actions of siponimod are determined by activation of pro-survival Akt and Erk 1/2 kinase signaling through S1PR1 in neurons.Previously, activation of Akt and Erk 1/2 signaling by FTY720 treatment has been shown to be anti-apoptotic and neuroprotective in neuronal cultures as well as in rodent models of stroke (Hasegawa et al., 2010), traumatic brain injury (Ye et al., 2016), and Parkinson’s disease (Zhao et al., 2017; Zhang and Wang, 2020).Microglia and astrocytes in the brain and Müller glial cells in the retina are the primary resident innate immune components, and their activation has been associated with glaucomatous neuronal injury (Mélik Parsadaniantz et al., 2020; Rolle et al., 2020).We observed glial cell activation in terms of morphological changes, proliferation, and upregulation of GFAP in reactive Müller glia and astroglia along the visual pathway in response to high IOP.This activation was significantly reduced in siponimod-treated mice, as confirmed with western blot and immunofluorescence analysis of retina, ON, and the brain tissues.The S1PRs expressed in astrocytes and microglia are also targets of siponimod and fingolimod, and their modulation has been reported to be neuroprotective (Noda et al., 2013; Qin et al., 2017; Rothhammer et al., 2017;Colombo et al., 2020).Further investigations into the specific inflammatory pathways affected in response to tissue-resident glial cell modulation by siponimod will unravel their roles in providing neuroprotective effects in chronic glaucoma.

Our study also demonstrates that S1PR1 expression in RGCs in the retina and neuronal cells in the dLGN is crucial to their survival in ON injury conditions.S1PR1 is expressed in sensory, dopaminergic, cortical, hypothalamic POMC neurons, and RGCs (Silva et al., 2014; Joly and Pernet, 2016; Ye et al.,2016; Zhao et al., 2017), and its deletion was observed to be embryonically lethal (Mizugishi et al., 2005).Therefore, we generated neuron-specific S1PR1 ablationin vivo

in S1PR1adult mice using engineered AAV-Cre recombinase constructs that efficiently transduced the neuronal cells or oligodendrocytes (Chan et al., 2017).In normal conditions, the neuronal deletion of S1PR1 did not significantly affect the inner retinal structure,function, and dLGN neuronal density.However, with glaucomatous injury,enhanced degenerative changes occurred in the inner retina and dLGN.These results suggested that the neuronal S1PR1 is necessary for neuroprotection against ON injury, but maybe not for their maintenance.Further, the protective effects of siponimod were impaired significantly in Neu-S1PR1mice.Among all S1P receptors, S1PR1 is a unique G-protein-coupled receptor,exclusively coupled with a Gi protein and has been linked to neuroprotection mechanism in neurons in different neurogenerative conditions, including stroke, traumatic brain injury, and Parkinson’s disease (Ye et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2017; Lucaciu et al., 2020).S1PR1 signal is transduced through Akt,Erk/MAP kinase pathways, and the S1PR1/STAT3 axis, promoting cell survival,proliferation, differentiation, and energy homeostasis (Pyne and Pyne, 2017).Activation of Jak2/STAT3 through the glycoprotein 130 receptor-dependent or independent mechanisms also promotes axon regeneration and neuronal survival effects (Smith et al., 2009; Nicolas et al., 2013).S1PR1 is a critical regulator of neurogenesis and neuronal cell apoptosis during development,and its deletion increased embryonic neuronal apoptosis (Mizugishi et al.,2005).Our results in this study suggest that S1PR1 is required for neuronal survival activity during ON injury conditions.Neuronal-specific S1PR1 deletion was observed to exacerbate the retinal and dLGN deficits and resulted in reduced efficacy of siponimod on activated glial cells.This could be due to the neuronal damage-triggering an enhanced inflammatory burst by upregulating the purinergic receptor responses in microglia.Extracellular nucleotides released by damaged neurons are reported to upregulate purinergic receptors of microglia and activate their inflammatory response, migration, and phagocytic ability (Illes et al., 2020;Pietrowski et al., 2021).We observed significantly reduced reactive gliosis in Neu-S1PR1mice with siponimod treatment in the retina, ON, and dLGN.These results suggest that the protective effects of siponimod in neuronal S1PR1 deleted mice might be through suppression of reactive gliosis in the retina and the brain.Suppression of pathogenic activation of astrocytes by S1PR1 modulation has previously been observed in various CNS inflammatory conditions (Chatzikonstantinou et al., 2021).Modulation of S1PR by either FTY720 or siponimod has been shown to suppress astrocytic activation.FTY720 treatment downregulated the expression of proinflammatory,chemoattractant, and neurotoxic molecules by activated astrocytes and microglia and enhanced the neuroprotective molecules like Cxcl12, IL33 Csf2, Chi3l3, and IL10 in the CNS in MS animal model (Choi et al., 2011;Rothhammer et al., 2017).S1PR agonist treatment has been shown to reduce the inflammatory response of astrocytes by reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines production, hampering the NFkB pathway, and blockage of nitric oxide (Miguez et al., 2015; Colombo et al., 2020; Kipp, 2020).

In addition, we evaluated whether the oligodendrocyte-specific deletion of S1PR1 has any effect on retinal and dLGN degeneration in experimental glaucoma and whether siponimod treatment imparted protective effects under such conditions.Oligodendrolineage cells express S1PR1 predominately,together with S1PR2 and S1PR5, and their expression levels vary during the maturation stage.Oligodendrocyte precursor cells preferentially express S1PR1, and its level decreases during differentiation, and S1PR5 becomes the dominant subtype in mature oligodendrocytes (Healy and Antel, 2016;Roggeri et al., 2020).In our study oligodendrocyte-specific S1PR1 deletion resulted in degenerative changes in the retina and dLGN similar to wt/control mice, and siponimod treatment also did not alter the neuroprotective effects in high IOP conditions, suggesting that the protective effects of the drug are not mediated through oligodendrocyte S1PR1 expression.However, S1PR signaling alteration is suggested to play distinct pathophysiological roles and displays specific subtype activation in neurodegenerative processes.S1PR1 ablated oligodendrocytes were previously shown to be more susceptible to demyelinating agents (Roggeri et al., 2020).

This study has some limitations that may require further investigations.In our findings, the mice treated with a single dose of siponimod via diet(10 mg/kg diet) showed significant neuroprotection against glaucomatous injury on the visual pathway.Further studies are required to understand the different dose effects of siponimod.We observed significant downregulation of glial activation with siponimod treatment in high IOP conditions both in the retina and the brain.However, we have not analyzed the inflammatory pathways affected by the siponimod treatment.S1PR1 is also expressed by the glial cells.Therefore, further investigations into the glial responses to siponimod treatment are required to understand the neuroprotective effects of siponimod in chronic glaucoma.Additionally, our study revealed that neuronal S1PR1 plays a critical role in glaucomatous injury, but we have not followed the long-term effects of its deletion in normal conditions.Despite these few limitations of this study, our findings suggest that modulation of neuronal S1PR1 by siponimod treatment could be beneficial in providing neuroprotection against glaucoma injury.

In summary, our results demonstrated that siponimod exerts neuroprotective effects on the retina and the brain in an ON-injury model.S1PR1 signaling in neurons plays a crucial role in neuroprotection and induces Akt/Erk pathways activation.Furthermore, this study showed that siponimod exerts beneficial effects through S1PR1 in neurons.The drug exhibited suppressive effects on the microglial activation and reactive gliosis along with neuronal cell preservation.Therefore, this study identifies that modulation of S1P receptors within the CNS may offer promising strategies to provide neuroprotection in CNS injury conditions.

Author contributions:

DB, VG, MM, AK and SLG designed the study; DB, RVW,NC, KP, and RR performed the experiments; DB, VG, and SLG analyzed the data;DB and VG wrote the manuscript; MM, SS helped to write the manuscript.All authors helped to write the manuscript preparation and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest:

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.No conflicts of interest exist between Novartis and publication of this paper.

Availability of data and materials:

The authors declare that all the relevant data, associated protocols, and materials supporting the findings of this study are present in the paper and/or the Additional Materials.

Open access statement:

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons AttributionNonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

Additional files:

Siponimod treatment reduced glial activation in optic nerves in chronic high IOP (8 weeks) condition.

Neuronal specific deletion of S1PR1 using AAV-PHP.eBSyn1-GFP-Cre in S1PR1 transgenic mice.

Chronic IOP elevation in different group mice eyes for 8 weeks following microbead injections.

Effects of siponimod on optic nerve damage under optic nerve injury induced by high IOP (8 weeks) in control and Neu-S1PR1 (AAVGFP-Cre) mice groups.

Effects of neuronal-specific S1PR1 deletion on dLGN degenerative changes under chronic IOP condition (8 weeks).

Deletion of S1PR1 in neurons reduces siponimod mediated upregulation of pro-survival signaling pathways Akt and Erk1/2 in the retina and brain.

Siponimod suppresses microglial activation and reactive astrocytes in dLGN in control mice and its protective effect is reduced in Neu-S1PR1 (AAV-GFP-Cre) mice in chronic optic nerve injury condition.

Effects of siponimod on glial activation in optic nerve under high IOP (8 weeks) induced optic nerve injury.

Transduction and specific deletion of S1PR1 in oligodendrocytes using AAV-PHP.eB-MBP-GFP-Cre in S1PR1 transgenic mice.

Chronic IOP elevation in different group mice eyes for 8 weeks following microbead injections.

Effects of oligodendrocyte-specific S1PR1 deletion on retinal degenerative changes under chronic IOP condition.

Effects of oligodendrocyte-specific deletion of S1PR1 on optic nerve and dLGN neurodegeneration under high IOP (8 weeks) optic nerve injury condition.

- 中国神经再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- Potential physiological and pathological roles for axonal ryanodine receptors

- Roles of constitutively secreted extracellular chaperones in neuronal cell repair and regeneration

- Melatonin, tunneling nanotubes, mesenchymal cells,and tissue regeneration

- MicroRNAs as potential biomarkers in temporal lobe epilepsy and mesial temporal lobe epilepsy

- Notice of Retraction

- Emerging roles of GPR109A in regulation of neuroinflammation in neurological diseases and pain