Zirconium metal organic cages: From phosphate selective sensing to derivate forming

Ziyuan Gao, Jia Jia, Wentong Fan, Tong Liao, Xingfeng Zhang

College of Material and Chemistry & Chemical Engineering, Chengdu University of Technology, Chengdu 610059, China

ABSTRACT Luminescent metal organic cages (MOCs) have attracted great interest as a unique class of sensing substrates.In this work, intrinsically fluorescent Zr-MOCs were successfully used as fluorescent probes for the sensitive and selective detection of phosphate anions in water and real samples.When the ligand and Zr ion clusters form a cage, the intrinsic fluorescence of the ligand was tuned from high to weak emission due to the ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) effect, and this weakened fluorescence can be restored by the addition of phosphate.The degree of fluorescence enhancement is positively correlated with the added phosphate concentration, and the efficacy of this strategy is demonstrated by a linear phosphate detection range of 5–500 μmol/L and a detection limit of 1.06 μmol/L.We discuss the interaction between phosphate and Zr in scattering spectrum and MS, respectively.In comparison to phosphate adsorption on Zr-metal organic frameworks (MOFs), where phosphate connects different numbers of cages, both blocking the LMCT effect and causing the cages to aggregate.We also found that the phosphate displaces the ligand from the cage when the phosphate concentration is further expanded, resulting in the formation of new derivatives.This derivative was shown to be useful as a Lewis acid catalyst and as a rare earth ion adsorbent.

Keywords:Zirconium metal organic cage Phosphate sensing Derivant forming Fluorescence enhancement Mass spectrometry

Phosphate plays an important role in biological systems and its concentration levels in body fluids can help diagnose such as rickets or hyperphosphatemia [1].In addition, although phosphate is widely present in natural environmental waters, high concentrations of phosphate can cause eutrophication in water bodies [2].Nowadays, most of the methods used to detect phosphate are ion chromatography or electrochemical analysis, which have long detection time and expensive instruments [3].It is faster and more efficient to use nanoparticles or small molecules with fluorescent properties for highly selective and sensitive sensing.However, because of the strong hydration of the anion in aqueous solution,highly selective sensing requires strong affinity of the phosphate for the probe.

Metal organic cages (MOCs) are another kind of rapidly developing porous materials after zeolite, metal organic frameworks(MOFs) and covalent organic frameworks (COFs) [4–7].Similar to MOFs, MOCs are discrete molecular combinations of metal ions or metal clusters and organic ligands with a specific morphology and cavity [8].UiO-66, as a star molecule of Zr-MOFs, built by trinuclear zirconium clusters are highly stable due to the high Zr−O bond energy (776 kJ/mol), showing excellent stability in aqueous solutions with neutral, acidic and weak basic conditions [9–11].Similarly, as a substructure of Zr-MOF, Zr-MOC should also have the same chemical stability as UiO.Recently, a class of Zr-MOCs has been reported, which possess various geometries with excellent properties in catalytic, sensing and adsorption [12–15].Highly stable Zr-MOCs have captivated more consideration not only for their robustness but also for reasonable solubility, permanent porosity,functionalization and potent applications in gas adsorption and selective separation.

In previous literatures, Zr-MOFs have been shown to form Zr−O−P bonds with phosphate groups, resulting in an extremely strong affinity.So far, Zr-MOFs have been used to selectively isolate and sense a variety of substances containing phosphate groups such as chlorophosphates, organophosphorus pesticides and phosphopeptides, but extremely high concentrations of phosphates can destroy the structure of MOFs [16–20].The fluorescence (FL) of terephthalic acid (BDC) as the ligand in the free state is weakened by the ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) when forming MOFs with Zr clusters.After the addition of phosphate, the LMCT effect is weakened once the phosphate is bound to the zirconium cluster,and thus the FL of BDC is restored.Taking advantage of this effect, Gu and his co-workers used UiO-66-NH2as a probe to detect phosphate [21].MOFs as a 3-dimensional structured nanomaterial,phosphate takes some time to diffuse into the interior of MOF to bind to the Zr clusters, allowing the FL of most of the ligands to be restored, while MOC as a 0-dimensional molecule and with multiple pore windows leading to a central internal cavity [22,23], have been demonstrated as water channels with high water permeability thus the Zr clusters bind more fully to the phosphate, and the FL of the ligand can be restored in a short time by complete binding [24].

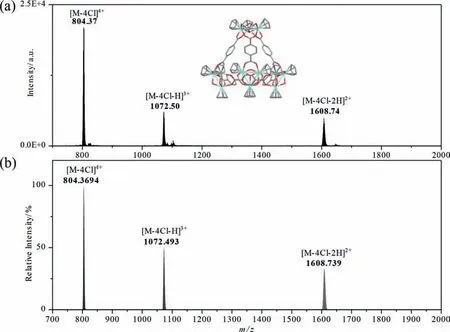

Fig.1.ESI-MS analysis of as-synthesized ZrT-1-NH2: (a) observed MS data, (b) simulated MS data.

Here we report a Zr-MOC, ZrT-1-NH2, synthesized with BDCNH2as ligand, as a fluorescent probe to sense phosphate in aqueous solutions.Slightly different from the FL mechanism of Zr-MOF,we also found an enhancement of scattered light during the binding process.This indicates that unlike Zr-MOF in which the Zr clusters act as anchor points to hold the phosphate in place, in this system the phosphate is bound to different Zr clusters on different Zr-MOCs as connecting points, linking different amounts of Zr-MOCs, which also block the LMCT effect and play a role similar to aggregation induced emission.And when the phosphate concentration exceeded beyond the linear range, a large amount of precipitation appeared in the solution, which we initially thought was a MOF or polymer formed by the MOCs being completely linked together by phosphate, but after further analysis, we found that the derivative was the phosphate replaced the ligands and cyclopentadienyl, thus forming an amorphous substance.This amorphous substance has the potential to act as a catalyst and adsorbent.

The ZrT-1-NH2was prepared by a modified hydrothermal method [25].After centrifugation and drying, the yellow crystals obtained was observed as a cubic structure under optical and electron microscopy (Fig.S1 in Supporting information).The crystals can be redissolved in methanol, ethanol or acetonitrile solutions of arbitrary concentration and then determined by using ESI-MS (Fig.1) and FTIR (Fig.S2 in Supporting information).We observed a series of peaks with +2 to +4 charges in the ESI-MS spectra as 804[M-4Cl]4+, 1072 [M-4Cl-H]3+and 1607 [M-4Cl-2H]2+, respectively.In addition, the actual isotopic peak distributions measured from the experimental data were consistent with the simulated calculated distributions for both ZrT-1-NH2(Fig.1) and ZrT-2 (Fig.S3 in Supporting information).

It is noteworthy that BDC-NH2as the ligand is intrinsically luminescent.Because the amino group in BDC is electron-donating,it provides the lone pair of nitrogen for the interaction withπ∗-orbital of the benzene ring, and consequently enhances the FL effi-ciency of the parent BDC molecule.But the obtained ZrT-1-NH2in 1:1 methanol aqueous solution exhibits a weak FL emission peak at 437 nm while excitation at 330 nm.The results were measured by adding 50 μL of 100 μmol/L phosphate solution to different concentrations of ZrT-1-NH2solution and left for 4 h.The results were shown in Fig.S4 (Supporting information).As the concentration of ZrT-1-NH2decreases, the slope of the working curve of fluorescence enhancement gradually decreases, which indicates that its sensitivity is also decreasing, so in this work, we used 100 μmol/L as the concentration of ZrT-1-NH2.To make the assay more effi-cient, we compared four different modes of action including static,vortex, ultrasound and microwave to treat the ZrT-1-NH2solution after adding phosphate, and the results are shown in Figs.S5–S8(Supporting information).Therefore, a 90 s microwave treatment time at medium-high heat was selected for the following sensing property investigation to ensure that the fluorescence equilibrium was reached in the phosphate assay.

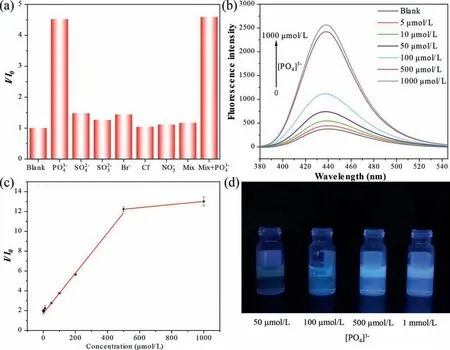

To test the specificity of the ZrT-1-NH2as FL sensor, the FL response of ZrT-1-NH2solution in the presence of various anions,including SO42−, SO32−, Br−, Cl−, NO3−, was collected.As shown in Fig.2a, the FL did not change significantly after the addition of other anions at the same concentration, while the phosphate ion could enhance its FL signals by about 4.5 times, and the same phenomenon occurred in the solution of mixed ions at the same concentration.This indicates that the other anions do not interfere with the determination of phosphate ions, and the ZrT-1-NH2has excellent selective recognition function.

Fig.2.(a) The FL response with various anions (100 μmol/L for each).(b) The FL intensity with 0–1 mmol/L [PO4]3−.(c) Linear plots of enhanced FL intensity from ZrT-1-NH2 solution as a function of phosphate concentration.(d) The photographs of FL intensity of ZrT-1-NH2 at different phosphate concentrations, excited at 365 nm.

FL enhancement experiments with different concentrations of[PO43−] were carried out at room temperature to test the sensitivity.The FL intensity gradually increased when different concentrations of phosphate solution were added (Figs.2b and d), and there was approximately 12-fold FL enhancement when phosphate was added to 500 μmol/L (Table S1 in Supporting information).The results of the linear range test of the analytical method are shown in Fig.2c set from 5 μmol/L to 1000 μmol/L.From the results, it can be seen that there is a good linear correlation at the[PO43−] from 5 μmol/L to 500 μmol/L, and the linear equation isy=0.02024x+1.74475,R2=0.9966.The LOD of the method was calculated (3σ/sensitivity) to be 1.06 μmol/L.It can meet the primary standard for phosphate released in terms of P as stipulated in Chinese National Standard 8978–1996 and the determination range of 0.04–1.00 mg/L (1.28–32 μmol/L) in terms of P, as stipulated in Chinese Environmental Standard 670–2013, is therefore of practical application.The test results of the water quality standard solution and the actual water samples collected from Chengdu city are shown in Table S2 (Supporting information).The results are consistent with ion chromatography, which proved to be reliable.Compared with other Zr-MOFs for phosphate sensing, Zr-MOCs do not have more advantages in terms of selectivity and sensitivity(Table S3 in Supporting information).However, other aspects show great advantages: (1) All the Zr-O clusters that can undergo affinity interaction are on the surface of the MOCs, which allows the phosphate ion to bind to it very quickly, without the need for a long time to make the phosphate slowly diffuse into the interior of the MOFs and interact with the internal Zr−O clusters to achieve maximum FL enhancement.The Zr-MOC probe used in this work can be tested by microwave heating for only 90 s and could achieve good accuracy and stability.(2) ZrT is soluble in organic reagents or aqueous solution of methanol.The solubility makes MOCs more promising for surface engineering applications than insoluble MOFs.Thus, we have used it as printing ink in the next work to print test strips or other patterns using an inkjet printer for better engineering applications and sensing.

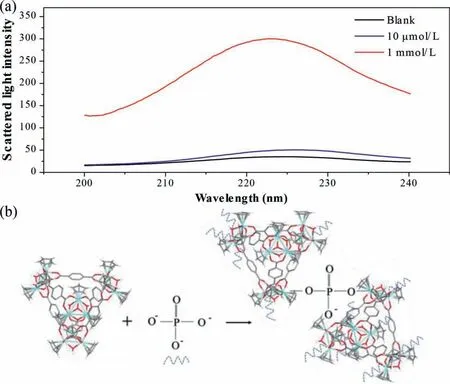

It can be seen from Fig.2c that the FL enhancement flattens out when the phosphate concentration increases to a certain level.This phenomenon also occurred on UiO-66, and the reason is that after all the Zr sites on the surface of MOF are occupied by phosphate, the diffusion to the interior is an extremely slow process,but the interior of MOC does not have Zr sites, and the existing theory cannot explain this, so we further tested the scattered light intensity.We found that, like the FL intensity, the scattered light intensity also becomes stronger with increasing phosphate concentration, as shown in Fig.3a.This indicates that there is agglomeration of MOC in solution.To verify this mechanism, we added a high concentration of phosphate directly to the solution of MOC,and a large amount of white precipitate (denote ZrT-P) was immediately generated in the solution (Fig.S9 in Supporting information).We speculate that the mechanism is as shown in Fig.3b.That is, a phosphate ion can bind multiple 1–3 Zr-MOCs through the P −O−Zr bond, a MOC molecule can also bind to several phosphate ions, and keep combining repeatedly until agglomerates are formed.This process, like the phosphate specific binding to the Zr site on UiO-66, also prevented the LMCT effect and thus enhanced the FL intensity.When the phosphate concentration is larger, the higher the degree of agglomeration, the more obvious the FL enhancement will be.

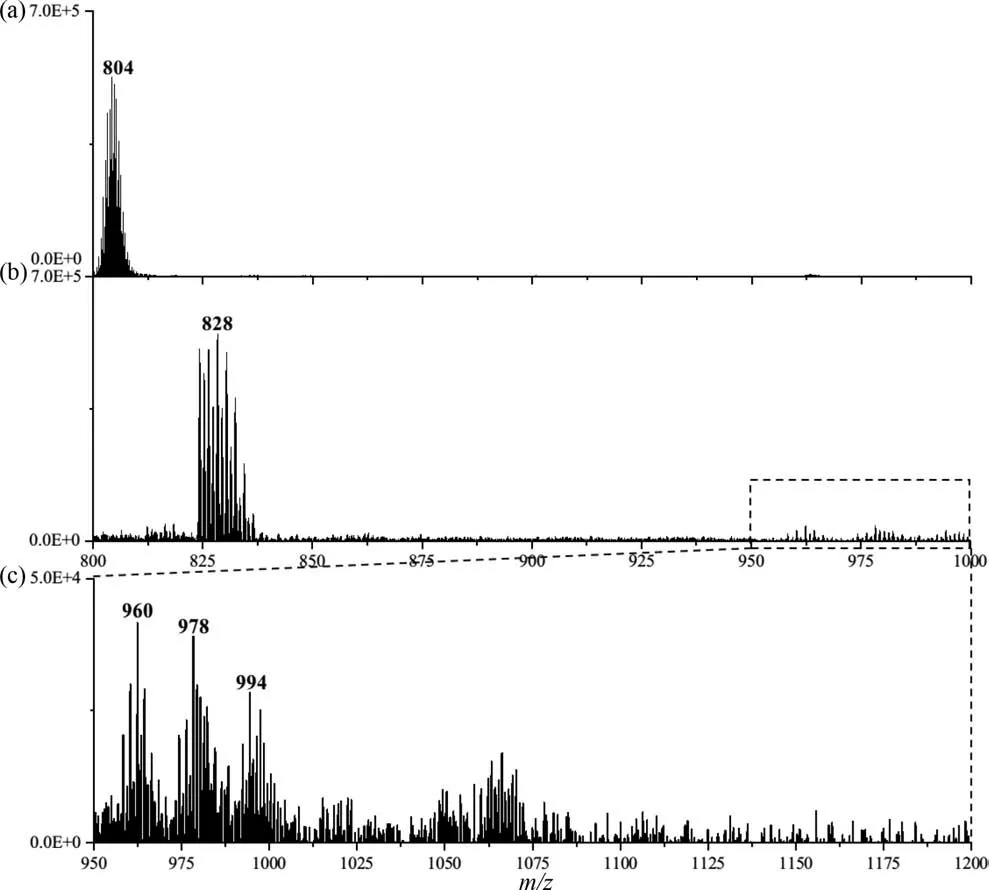

To verify this mechanism, we collected mass spectrometry data of ZrT-1-NH2solutions after adding different concentrations of phosphate ions.First, the peak intensity ofm/z804 decreased dramatically, which might be caused by the binding of ZrT-1-NH2to the added phosphate (Figs.4a and b).Secondly, we observed the appearance of many clustered peaks with very small intensities, and these may be the products of what we believe to be the binding of the MOC to the phosphate.As shown in Fig.4c,upon closer inspection, we found several clustered peaks of higher intensity that were consistent with what we had speculated (Table S4 in Supporting information).Among them,m/z828 might be[M+PO4]4+or [2M+2PO4]8+,m/z960 might be [2M+3PO4]7+,m/z978 might be the summation peak of 960 with water, andm/z994 might be [3M+3PO4]10+, whose simulated spectra are shown in Fig.S10 (Supporting information).It is noteworthy that the noise of the mass spectrum is two to three orders of magnitude larger after the addition of phosphate than when it is not added, which means that more possible ionized substances appear in the solution, making it very difficult to analyze many clustered peaks with very low intensity.In addition, we speculate that the binding probability of the cage to phosphate is diverse and random, which leads to high intensity MOC ion peaks whose intensity would be randomly distributed over each binding probability, resulting in low signal values for each cluster and increasing the difficulty of our analysis.

Fig.3.(a) The scattered intensity with 10 μmol/L and 1 mmol/L [PO4]3−.(b) Schematic depicting the phosphate induced Zr-MOCs agglomeration.

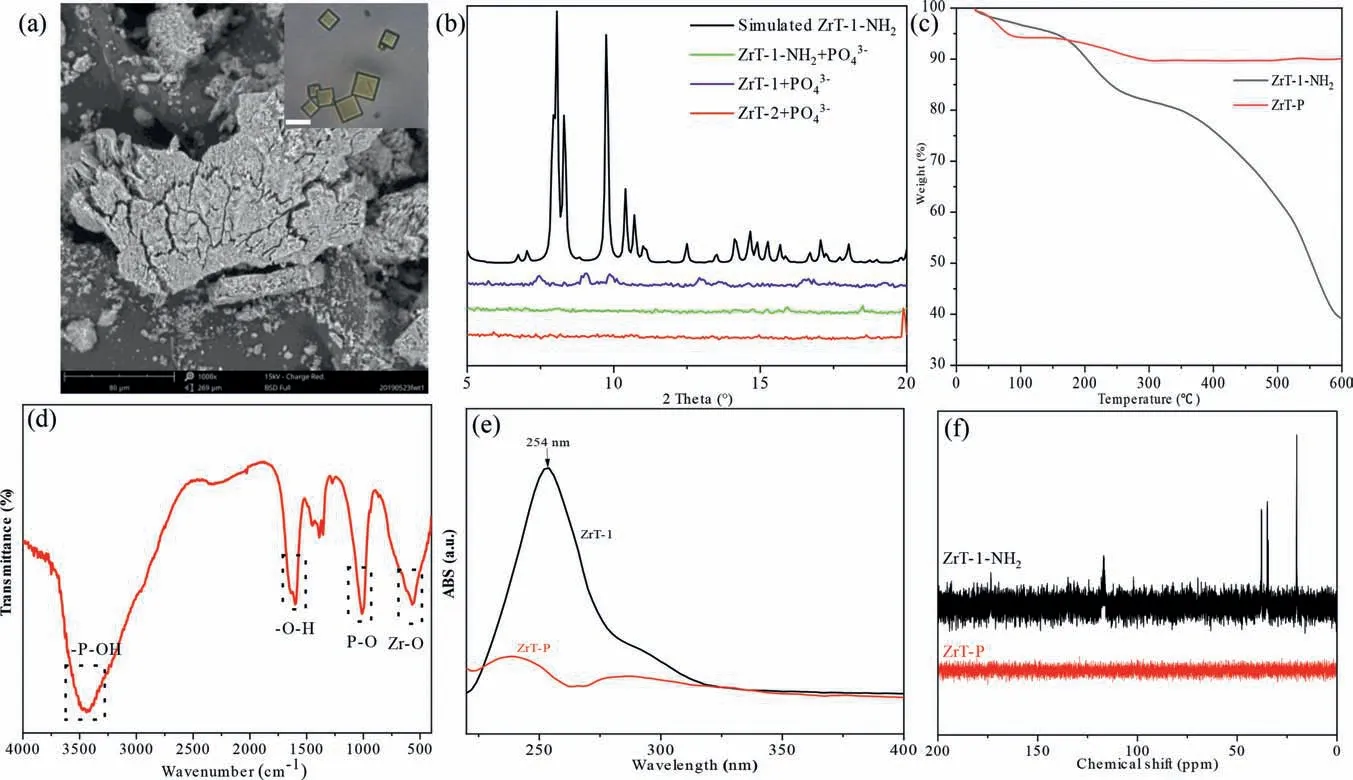

We compared the precipitates produced by adding high concentrations of phosphate to ZrT-1 (BDC as the ligand), ZrT-1-NH2(BDC-NH2as the ligand) and ZrT-2 (1,3,5-trimesic acid as the ligand) solutions and found that they were all white precipitates,which make us confused.ZrT-1-NH2is an orthorhombic yellow crystal, and if it is combined with phosphate to form an agglomerate, the -NH2group will absorb visible light to produce color,but since ZrT-P is white then presumably its must have lost its chromophore.We surmised that the organic ligand could be removed by introduction of phosphate, so a series of characterizations of ZrT-P were performed.SEM results showed that ZrT-P has lost its orthorhombic structure and is amorphous (Fig.5a), while the XRD spectra of the three ZrT crystals with phosphate bonded to produce white precipitates are almost identical, showing that they have lost the crystalline structure of ZrT (Fig.5b).And the thermogravimetric spectra showed that ZrT-P had better thermal stability (Fig.5c).Between 30 °C and 600 °C, the mass loss was only 9.92%, of which 5.70% was lost before 100 °C, accounting for most of the mass loss, which should be caused by the incomplete drying of water.Comparing with the thermogravimetric analysis of ferrocene (Fig.S11 in Supporting information), we can see that the organic ligand will start to decompose continuously after 400 °C until only the metal oxide is left by decomposition.The FTIR results of ZrT-P show a broad peak at 3400 cm−1for theσ-P−OH absorption peak as well as the hydroxyl vibration peak of the coordinated water molecule, 1622 cm−1for the bending vibration peak of the adsorbed water molecule, 1000 cm−1for the peak appearing as theσ-P−Oabsorption peak, and 600 cm−1for the absorption peak appearing as theσ-Zr−Oabsorption peak (Fig.5d).In the whole IR spectrum, we did not observe the absorption spectrum of the organic ligand BDC-NH2, nor the cyclopentadienyl group in Zr-MOCs.Further UV–vis absorption spectrograms confirmed that the benzene ring structure was no longer present in ZrT-P (Fig.5e).ZrT-1-NH2was slightly soluble in water that we could get a weak signal in13C NMR (Fig.5f).but ZrT-P was easily soluble in water,and we still could not observe signals in13C NMR.The absence of any distinct weight loss from decomposition of ZrT-P indicates the bridging ligands were fully removed during the treatment process, further supported by CHN analysis (Table S5 in Supporting information).All the above tests indicated that not only the organic ligand was converted by phosphate in the process but also the bonding of the Zr-cyclopentadienyl is broken.A similar phenomenon occurred in the study of Lin’s group, who also obtained an amorphous derivative consisting only of Zr−O−P by immersing UiO-66 in a high concentration of sodium phosphate or phosphoric acid [21].

We further tested the dissolution of ZrT-P in various common solvents and compared it with that of ZrT-1 and ZrT-1-NH2.It can be seen that ZrT-P is easily soluble in water but not in any other organic solvents, while Zr-MOCs can be soluble in other organic reagents (Table S6 in Supporting information).Using the property that ZrT-P is insoluble in organic solvents, we used it as a heterogeneous catalyst to catalyze the reaction of benzaldehyde with o-phenylenediamine to form 2-phenylbenzimidazole.Commonly used catalysts for this reaction include Ag2CO3, carbonloaded HfCl4, ZrOCl2, phosphoric acid, and polyphosphoric acid[26].From the results of product generation, the same weight% of ZrT-P and phosphoric acid, under the same reaction conditions, the conversion rate ofo-phenylenediamine using ZrT-P as the catalyst was 34.8% and using phosphoric acid as the catalyst was only 2.0%,indicating that the potential of ZrT-P as a Lewis acid catalyst.Another application is the adsorption of rare earth ions in aqueous solutions.ZrT-P was added to an ethanol solution containing Sm3+,Eu3+and Tb3+, placed in a shaker-oven at 150 rpm overnight.After centrifugation, the concentration of rare earth ions in the supernatant was determined by ICP-MS, and it was found that almost all rare earth ions were adsorbed (Table S7 in Supporting information), proving its potential as an adsorbent for rare earth elements or radioactive elements.

Fig.4.The observed MS data before (a) and after (b) adding phosphate, (c) the MS data between m/z 950–1000.

Fig.5.(a) The SEM image of ZrT-P, inset: the photography of ZrT-1-NH2, scale bar 5 μm.(b) The PXRD of derivatives from three Zr-MOCs and phosphate.(c) The TGA data of ZrT-1-NH2 and ZrT-P.(d) FTIR of ZrT-P.(e) UV absorb spectrum of ZrT-1 and ZrT-P.(f) The 13C NMR spectrum of ZrT-1-NH2 and ZrT-P.

In conclusion, we used Zr-MOC as a FL probe for the first time to sense phosphate in water samples, which has the advantages of high selectivity, good linearity and low detection limit and can be applied to actual sample detection.We studied the interaction of Zr-MOC with phosphate for the first time by scattering spectrometry and mass spectrometry.It was found that phosphate can specifically bind to the Zr site at low concentrations, blocking the LMCT effect, and can agglomerate several cages meanwhile, resulting in enhanced FL; phosphate replaces the ligands constituting the cages at high concentrations, forming an amorphous derivative,which was characterized and analyzed for preliminary applications of catalysis and adsorption.It is believed that with further studies,the derivatives are expected to have wider applications in catalysis,metal ion adsorption,etc.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the financial support from Chengdu University of Technology (No.10912-SJGG2021-06843).

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.12.035.

Chinese Chemical Letters2022年9期

Chinese Chemical Letters2022年9期

- Chinese Chemical Letters的其它文章

- A review on recent advances in hydrogen peroxide electrochemical sensors for applications in cell detection

- Rational design of nanocarriers for mitochondria-targeted drug delivery

- Emerging landscapes of nanosystems based on pre-metastatic microenvironment for cancer theranostics

- Radiotherapy assisted with biomaterials to trigger antitumor immunity

- Development of environment-insensitive and highly emissive BODIPYs via installation of N,N’-dialkylsubstituted amide at meso position

- Programmed polymersomes with spatio-temporal delivery of antigen and dual-adjuvants for efficient dendritic cells-based cancer immunotherapy