Saline-Alkali Tolerance in Rice: Physiological Response, Molecular Mechanism, and QTL Identification and Application to Breeding

Ratan Kumar Ganapati, Shahzad Amir Naveed, Sundus Zafar, Wang Wensheng, Xu Jianlong,

Review

Saline-Alkali Tolerance in Rice: Physiological Response, Molecular Mechanism, and QTL Identification and Application to Breeding

Ratan Kumar Ganapati1, Shahzad Amir Naveed1, Sundus Zafar2, Wang Wensheng1, Xu Jianlong1, 2

(Institute of Crop Sciences, National Key Facility for Crop Gene Resources and Genetic Improvement, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing 100081, China; Shenzhen Branch, Guangdong Laboratory for Lingnan Modern Agriculture, Agricultural Genomics Institute at Shenzhen, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Shenzhen 518120, China)

Salinity-alkalinity is incipient abiotic stress that impairs plant growth and development. Rice () is a major food crop greatly affected by soil salinity and alkalinity, requiring tolerant varieties in the saline-alkali prone areas. Understanding the molecular and physiological mechanisms of saline-alkali tolerance paves the base for improving saline-alkali tolerance in rice and leads to progress in breeding. This review illustrated the physiological consequences, and molecular mechanisms especially signaling and function of regulating genes for saline-alkali tolerance in rice plants. We also discussed QTLs regarding saline-alkali tolerance accordingly and ways of deployment for improvement. More efforts are needed to identify and utilize the identified QTLs for saline-alkali tolerance in rice.

saline-alkali tolerance; physiological mechanism; molecular mechanism; marker-assisted backcrossing; rice

Saline-alkali stress results in significant plant damage and is a critical worry for 932 million hectares of land worldwide, with 100 million hectares in Asia (Wang et al, 2011; Wei et al, 2017). This soil covers 6.2% (7.66 × 106hm2) of the land area in northeast China(Yang et al, 2008). Thus, it impedes world crop production (Wang et al, 2016). More alarmingly, approximately 2.0 × 104hm2of land is newly salinized or alkalized every year (Wang et al, 2009). Salt stress is mainly from NaCl, Na2SO4, and other neutral salts, which causes ion toxicity and osmotic stress (Bhatt et al, 2020). Both of these aspects can cause plant metabolic disorders. Alkali stress induced by NaHCO3and Na2CO3with high pH (7.1–9.5) severely affects cell pH stability, demolishes cell membrane integrity, and decreases root vigor and photosynthetic function (Guo et al, 2014). The high pH damages plants directly by nutritional mineral deficiencies such as iron (Fe), manganese (Mg), zinc(Zn) and phosphorus (P) (Nandal and Hooda, 2013; Li et al, 2019). These two stresses result in severe ion imbalance, osmotic instability, disruption of the antioxidant system, and plant growth inhibition (Wang et al, 2020; Zeng et al, 2021).

Rice () is inherently salt-sensitive at the seedling and reproductive stages, thereby, saline-alkali stress is a big threat (Munns and Tester, 2008; Rao et al, 2013). For saline-alkali soil with pH 9.8, the yield is reduced by 25%, 37% and 68% for tolerant, moderately tolerant, and sensitive rice cultivars, respectively (Singh et al, 2021).It has a strong detrimental effect on rice over the entire growth span and decreases seed germination rate, seedling growth, biomass synthesis, primary root length, number of tillers, and panicle weight (Ganapati et al, 2020) by decreasing nutrient solubility, increasing external osmotic pressure, and disrupting ion imbalance, especially cellular pH stability (Chen et al, 2009). Therefore, to combat this stress, rice cultivars with high saline-alkali tolerance are being developed to maintain grain output in saline-alkali-affected areas for ensuring food security (Fita et al, 2015).

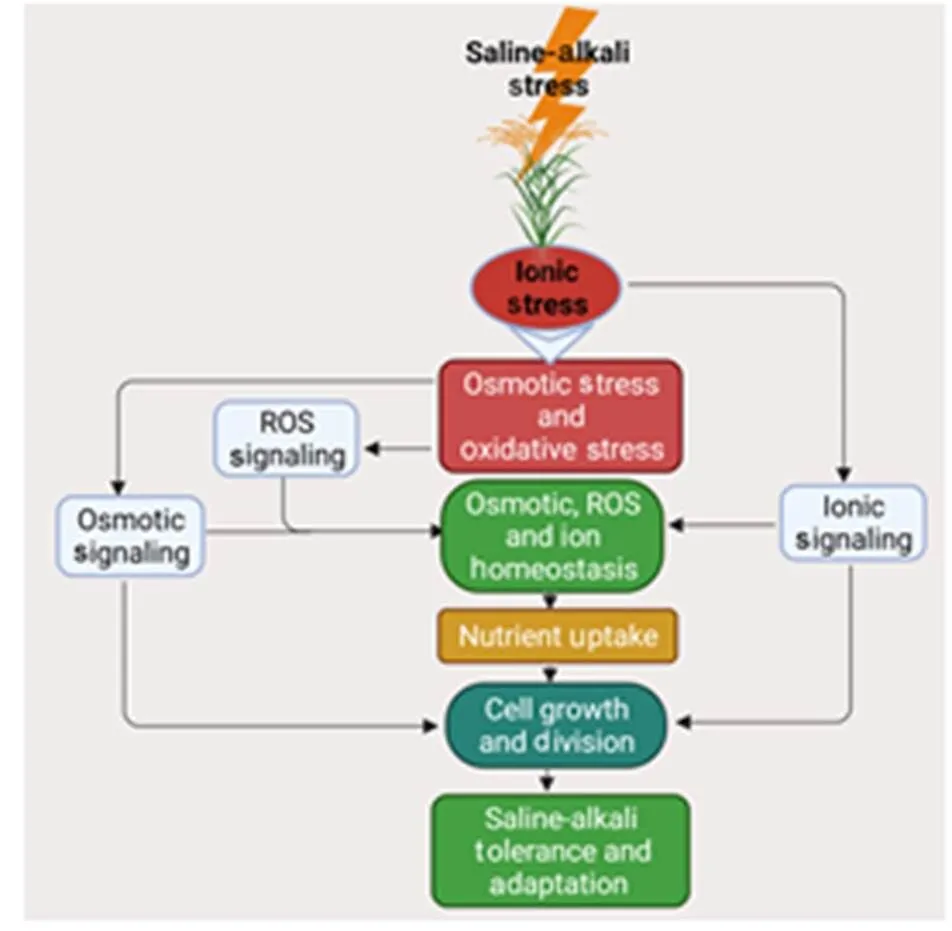

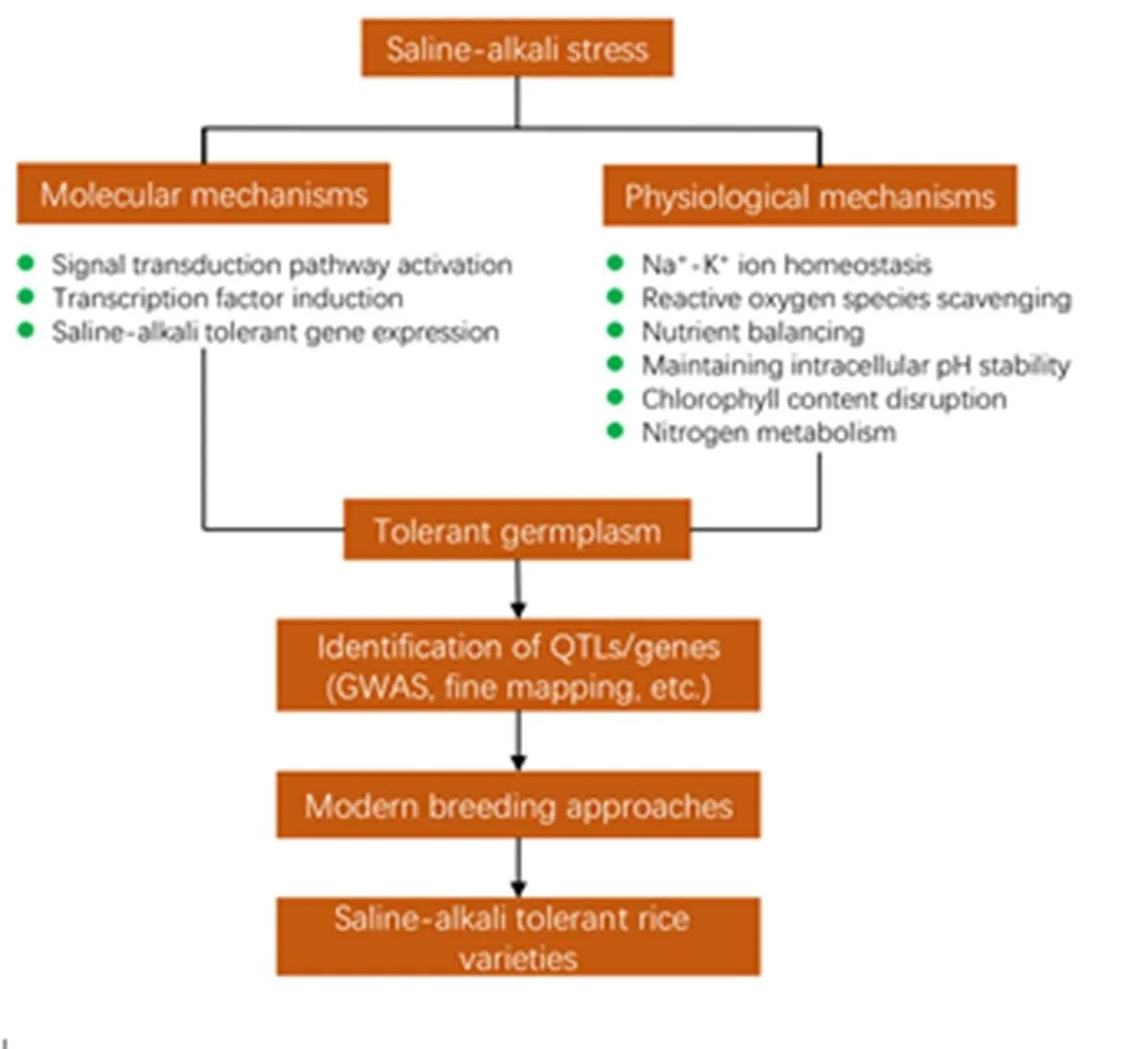

Fig. 1. Diagrammatic representation of saline-alkali stress response to rice.

Modified from Kumar et al (2013). ROS, Reactive oxygen species.

Saline-alkali tolerance is governed by complex genetic, molecular, and physiological mechanisms. In rice, different developmental stages play different mechanisms to deal with saline-alkali stress. Numerous salinity and alkalinity-responsive genes and QTLs have been identified in rice, but very few have been successfully incorporated into commercial germplasm (Kotula et al, 2020). However, the complexity of responses to salinity-alkalinity and the lead components of ionic, osmotic, and oxidative stress are main issues for developing saline-alkali tolerant rice varieties. Here, we critically evaluated the mechanisms of saline-alkali tolerance in physiological response, genetic and molecular levels, and proposed strategies for efficient utilization of saline-alkali tolerance QTLs in rice breeding.

Physiological mechanisms: Plant response to saline-alkali stress

Ion toxicity is the primary cause of saline-alkali stress, followed by osmotic stress and oxidative damage. With high pH due to alkalinity, the root is severely damaged (Li et al, 2009), and alkalinity also causes deficiencies of nutritional minerals such as Fe, Mg, P and Zn (Javid et al, 2011; Li et al, 2019). Thus, plant growth in the saline-alkali soil is seriously smothered (Kumar et al, 2013)(Fig. 1).

Higher salt concentration induces hyper-osmolality and ionic imbalance in rhizosphere (Hasegawa, 2013). Hence, plants absorb a large amount of Na+which moves sequentially from soil solution into outer root cells, to root xylem vessels, and translocates from root to shoot and then vapor interface of large transpiration flux throughout the leaves (Munns and Tester, 2008), thus finally inhibiting the absorption of other nutrients, such as K+, consequential in ion toxicity (Assaha et al, 2017). In these conditions, the external water potential is too low, causing osmotic stress in root cells, leading them to accumulate compatible solutes in the cytoplasm, lowering their water potential, and ensuring that the volume and turgor pressure of the cells are within the proper range to prevent water loss. In addition, this also keeps the stomata open, and CO2concentration in rice leaves is at a high level, which can reduce the inhibition of plant photosynthesis (Türkan and Demiral, 2009). This typical state is disrupted by saline-alkali stress, causing reactive oxygen species (ROS) to build in plants that damages the biomembrane system and injuries until wilting (Wang et al, 2009).

Ion homeostasis

Saline-alkali stress is commonly caused by high concentrations of Na+, Cl–, HCO3–and CO32–in the soil (Qin and Huang, 2020). Na+and K+get into the cell using the same set of transporters and compete with each other (Greenway and Munns, 1980). Osmoregulation, protein synthesis, cell turgor maintenance and appropriate photosynthetic activity all require K+(Ashraf and Harris, 2004), making catalytic activity of many central enzymes, and excess Na+(phytotoxic) competes with K+for absorption across plant cell plasma membranes (Fu and Luan, 1998). Thus, maintaining cellular Na+/K+homeostasis is crucial for a plant to adjust to saline-alkali stress (Yang and Guo, 2018).

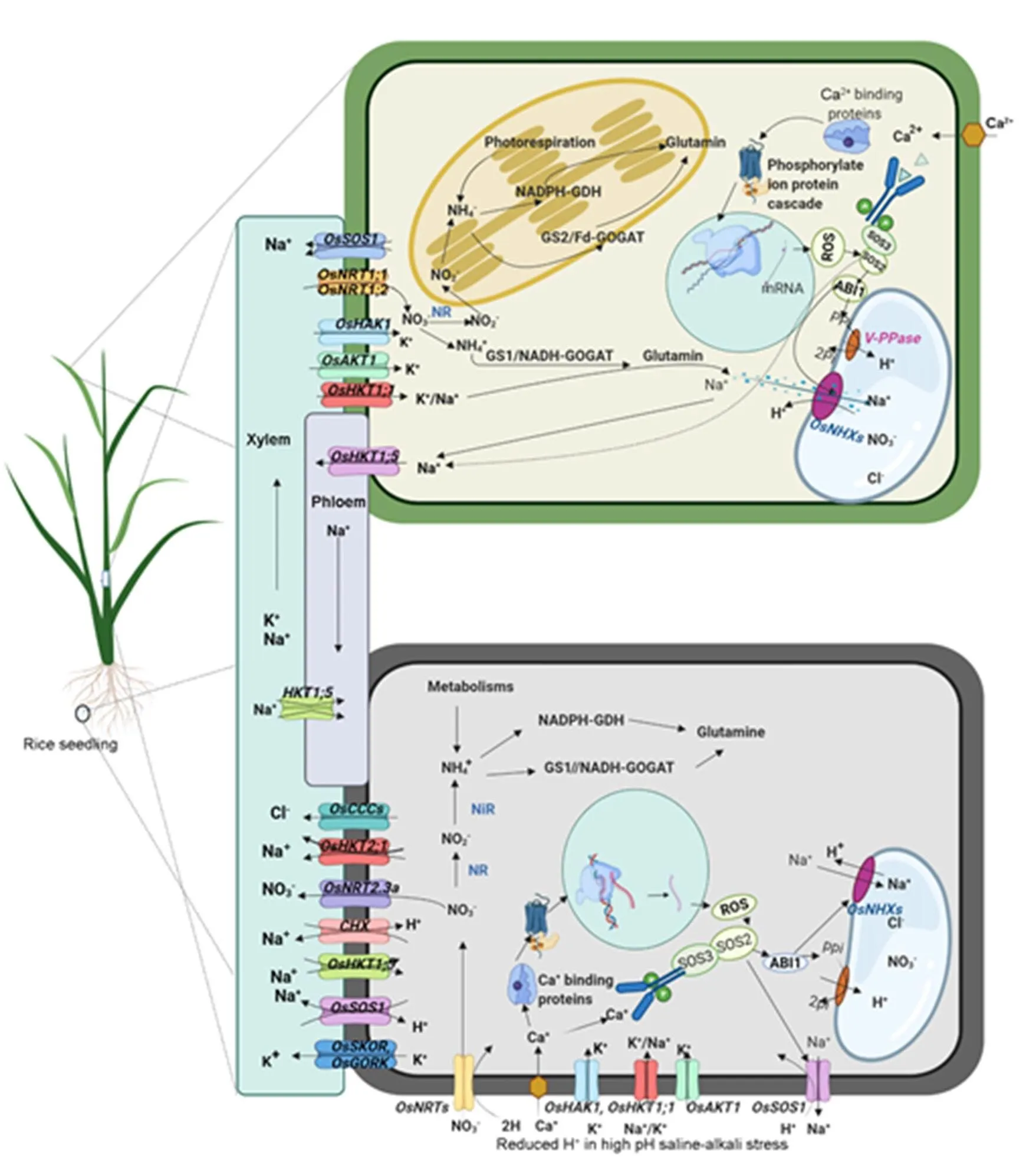

Mechanisms to refrain from accumulating cytoplasmic Na+at toxic levels restrict excess Na+uptake, an increase in Na+efflux, and compartmentalization of Na+in the vacuole (Yang and Guo, 2018). In the rice plasma membrane, exclusion of Na+from shootsis regulated by Na+/H+antiporter () that maintainsa lower cellular Na+/K+ratio and increases salt tolerance (Martínez-Atienza et al, 2007;El Mahi et al, 2019). Na+from shoots in maintaining Na+/K+governed byin roots is considered a key factor in saline-alkaline tolerance (Chuamnakthong et al, 2019). During salinity stress,,/and/are members of the rice high-affinity K+transporter (HKT) family, which helps to minimize Na+accumulation in leaves (Ren et al, 2005). Under the saline-alkalistress, a large influx of Na+into the cytoplasm takes down the membrane potential to the resting potential, which activates the K+outflow channel (SKOR and GORK) and breaks the stable equilibrium of the K+/Na+ratio(Fig. 2). Thus, shaker-like potassium channels OsSKORand OsGORKregulate K+in rice (Kim et al, 2015). Silicon enhances K+loading to the xylem for translocation and upregulates the expression ofand(Yan et al, 2021).,,,,,andtransport Na+or both Na+and K+in the cytoplasm to maintain Na+/K+equilibrium and govern rice response to salt stress (Yang et al, 2014; He et al, 2019).

Under alkali stress, Na+/H+-antiporter (NHX) is major sources of proton leakage by alkali cation/proton antiporters like NHX1 and NHX2, and CHX regulates the cytosolic pH (Sze and Chanroj, 2018). Na+/H+antiporters,,,,andoperate cytoplasmic excess Na+to vacuole through compartmentalization and enhance tolerance to saline-alkali stress (Liu et al, 2010;Fukuda et al, 2011).also promotes Na+/H+exchange and increases rice resistance to salt stress by pumping H+from the cytosol into the vacuole (Liu et al, 2010).

Under saline-alkali stress,encourages root elongation by lowering the influx of Na+and H+in rice (Ni et al, 2020). At the same time, the signaling molecule Ca2+needs to be balanced in the cytoplasm and gets into the vacuole. In rice,transports Ca2+into the vacuoles and is involved in Ca2+homeostasis in cells that suffer from high concentrations of Ca2+(Kamiya et al, 2006). Under the complex stress, rice chloride channel proteins OsCLC1, OsCLC-1 and OsCLC-2promote plant development and salt stress tolerance under ionic stress via transporting chloride ions across the vacuolar membrane (Diédhiou and Golldack, 2006). On the other hand, the SLC4 family consists of ten genes encoding proteins that transport HCO3−[majority with Na+-coupled HCO3−transporters (NCBTs)] across the plasma membrane and maintain inter- cellular pH by contributing to the movement of HCO3−. The rice genome contains four SLC4-like genes named(Parker and Boron, 2013). OsMAPK5 and OsMAPK44 belong to the mitogen-activatedprotein kinase (MAPK) cascade and play an important role in ion-exchange salt tolerance mediating stress responses (Xiong and Yang, 2003).

Fig. 2. Ion homeostasis pathways and nitrogen metabolism of rice under saline-alkali stress.

AKT, Low-affinity K+transporter; GDH, Glutamate dehydrogenase; GOGAT, Glutamate synthase; GS, Glutamine synthetase; HAK, K+transporter; HKT, High-affinity K+transporter; NHX, Na+/H+exchanger; NiR, Nitrite reductase; NR, Nitrate reductase; SOS, Salt overly sensitive; ABI1, Abscisic acid insensitive 1; NADH, Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; NADPH, Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; ROS, Reactive oxygen species; Pi, Phosphoric acid; PPi, Pyrophosphoric acid. Modified from Martínez-Atienza et al (2007), Pérez-Tienda et al (2014), Liang et al (2015), Hanin et al (2016) and El Mahi et al (2019).

Osmotic adjustment

Saline-alkali stress causes osmotic stress and promotes the biosynthesis and accumulation of compatible osmolytes such as sugars, proline, glycine betaine, polyamines and proteins from the late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) super-family. These osmolytes protect plants by reducing the cell osmotic potential and stabilizing proteins and cellular structures (Chen et al, 2021). The proline biosynthesis genes,,,andincrease proline accumulation and improve rice tolerance to osmotic and saline-alkali stresses (Lv et al, 2014).,,,,, andgenes coding for trehalose-6-phosphate synthase/phosphatase can improve tolerance to high pH (~9.9), high electrolytic capacitor (~10.0 dS/m) and severe drought (30%–35% soil moisture content)(Joshi et al, 2020). Some alkaloids such as diterpenoid and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis may contribute to the greater tolerance to saline-alkali stress in rice (Li W X et al, 2020).and-green fluorescent proteins encode a monosaccharide transporter that increases monosaccharide accumulation and confers hypersensitivity to salt stress in rice (Cao et al, 2011). Salinity stress disrupts the sugar homeostasis in rice.andare major SWEET transporters that regulate sucrose transport and give tolerance under drought and salinity stresses (Mathan et al, 2021). In rice, glycine betaine (GB) is oxidized from choline by choline monooxygenase CMO to form betaine aldehyde, and finally betaine aldehyde is catalyzed by betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase (BADH) encoded by the betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase gene, resulting in the accumulation of GB, thus enhancing the tolerance of rice to salt stress (Rathinasabapathi et al, 1997; Cha-Um et al, 2007; Hasthanasombut et al, 2011).,,andmay improve resistance to salinity and osmotic stresses (Yu et al, 2016). Besides these, the antioxidant activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), peroxidase and ascorbate peroxidase (APX) in the roots are increased at high pH under alkali stress (Hong et al, 2007)., encoding fructokinase-like protein2, accounts for its influence on sugar metabolism in rice seedlings under saline-alkali stress (Chen et al, 2019).encodes a small plant-specific membrane protein that improves salt tolerance by increasingexpression and free proline content under salt stress (Chen Y H et al, 2020). Under salinity stress,andare upregulated, which may influence the synthesis and accumulation of proline, sugar and LEA proteins, all of which have a role in salt tolerance (Zhang X et al, 2020).

ROS scavenging

As secondary stress, both ionic and osmotic stresses induce ROS accumulation under saline-alkali stress. Alkaline stress induces a conspicuous accumulation of ROS, i.e. superoxide anions (O2·−) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), in rice roots and leads to cell damage (Mittler et al, 2011;Zhang et al, 2017). These accumulated ROS disrupt the normal physiological functions of cells, resulting in metabolic disorders. Plants also have a set of scavenging systems, including enzymes and antioxidants for reducing ROS stress (Fang et al, 2021). The enzymatic scavengers include respiratory burst oxidase homologs (RBOHs), SOD, APX, CAT, glutaredoxin (GRX), glutathione peroxidase (GR), glutathione S-transferase (GST), and glutathione peroxidase (GPX) (Yang and Guo, 2018).

RBOHs are key signaling knobs in the ROS gene network of plants, integrating a multitude of signal transduction pathways with ROS signaling (Suzuki et al, 2011). Under the saline-alkali stress,reduces ROS accumulation, scavenging the accumulated ROS by,and exhibits tolerance in rice plants (Liu X L et al, 2022).NaCl activatesthrough abscisic acid-insensitive 4 () expressions and promote ROS production (Luo et al, 2021). SOD, the first enzyme in the antioxidant system, transforms accumulated O2·−molecules into O2and H2O2, and then POD, CAT and APX resolve H2O2into H2O and O2. Cell membranes are severely damaged by alkali stress and the contents of malondialdehyde (MDA) and H2O2increase significantly, which stimulates the antioxidant defense system and finally scavenge the accumulated ROS (Zhang et al, 2017; Hasanuzzaman et al, 2021). The overexpression ofexhibits stronger resistance under alkali (NaHCO3) treatment with significant upregulation of,,/andthat regulate ROS scavenging (Guan et al, 2016). Overexpression lines ofandshow lower accumulation of O2·−and H2O2under salt stress (Guan et al, 2017).,which encodes a Snf2 family chromatin remodeling ATPase, can reduce ROS generation and improve alkaline tolerance under alkaline circumstances (Guo et al, 2014).encoding monophosphate dehydrogenase is down- regulated and reduces cell death under high pH saline-alkali stress (Zhang et al, 2017).

Non-enzymatic antioxidants for ROS scavengers include ascorbic acid (ASA), alkaloids, carotenoids, flavonoids, glutathione (GSH), phenolic compounds, and α-tocopherol (Hasanuzzaman et al, 2020). Saline-alkali stress can increase both ASA and GSH contents and then maintain protein stability and prevent membrane lipid peroxidation. Apart from removing free radicals, ASA and GSH also cooperate with APX, GR and other antioxidant enzymes to enhance the antioxidant system and maintain a balanced oxygen metabolism in cells to further alleviate the damage caused by saline-alkali stress (Fang et al, 2021). Rice glyoxalase II (OsGLYII-2) is a glutathione-responsive enzyme that aids in salinity adaptation by improving photosynthetic efficiency and boosting the antioxidant pool (Ghosh et al, 2014).,,andcan increase GSH levels and improve abiotic stress tolerance, such as salt, osmotic and oxidative stresses (Wu et al, 2015; Lima-Melo et al, 2016). In addition, GDP-mannose pyrophosphorylase OsVTC1-1 and dehydroascorbate reductase (OsDHAR) play critical roles in plant salt tolerance by promoting the ASH scavenging of excess ROS (Qin et al, 2016). Rice plants also accumulate flavonoid glycosides by UDP-glucosyltransferase encodedbygene, which protects the cell from abiotic stress (Dong et al, 2020).

Nutrient balancing

Soil salinity may cause deficiencies or imbalances in plant nutrients due to the competition of Na+and Cl−with many plant nutrients such as Ca2+, K+and N-NO3−. A distinguished reduction in plant growth may occur under saline conditions due to specific ion toxicities (e.g., Na+and Cl−) and ionic imbalances (Forni et al, 2017). Furthermore, increased NaCl concentration can decrease N, P, Ca, K and Mg levels in many plants (Naeem et al, 2017). Alkaline soils are characterized by high concentrations of carbonates (CO32−) and bicarbonates (HCO3−), along with high pH and poor amounts of organic carbon which impair nutrient availability to the rhizosphere (Msimbira and Smith, 2020). High concentration of HCO3–in the soil causes inhibition of root growth and respiration (Alhendawi et al, 1997), and the higher pH results in nutrient imbalance in crop production by affecting the bioavailability of Fe, Zn, P, Cu and B (Chen et al, 2011).

Fe occurs mainly as insoluble hydroxides and oxides in saline-alkali soil, limiting its bioavailability for plants (Romera and Alcántara, 2004). Moreover, saline-alkali soil contains a high Na+concentration and pH. Buffering pH to 8.3 leads to Fe’s substantial precipitation and other nutrients in a mural habitat (Donnini et al, 2012). To cope with low Fe availability in saline-alkali soil, plants have evolved several strategies: acidification, reduction, and chelation. Stronger rhizosphere acidification is resulting from H+-ATPase-mediated proton extrusion followed by reduction of ferric iron (Fe3+) to ferrous iron (Fe2+) by ferric-chelate reductase, and uptake of Fe2+into root cells by IRON REGULATED TRANSPORTER1 (IRT1) (Lucena et al, 2015; Li et al, 2016). In rice, the expression levels of,,,,andare enhanced by saline-alkali and the plants can acquire Fe more efficiently, thus contributing to the higher accumulation of Fe (Li et al, 2016).

Like Fe, Zn is sparingly available in saline-alkali soils due to their poor solubility at high pH. In rice, Zn deficiency is common in neutral to alkaline pH soils (Rengel, 2015).is a cytokinin type-B response regulator that regulates Zn uptake by directly influencing the expression of Zn-regulated transporter genes to salt stress (Liu C T et al, 2022).contributes to root Zn uptake in rice under Zn-limited conditions (Huang et al, 2020).

Saline-alkali stress affects photosynthesis and carbohydrate synthesis and suppresses biomass and phosphorus(P) accumulation and translocation (Zhu, 2001). More tolerant rice varieties have a stronger capacity to absorb and translocate P for grain filling, especially in severe saline-alkali soils (Tian et al, 2017).

Maintaining intracellular pH stability

High pH is a characteristic feature of saline-alkali stress, which predominantly harms the plant root system by destroying root tissue and reducing root surface area, leading root cells to lose their physiological function (Munns and Tester, 2008; Robin et al, 2016). Under saline-alkali stress, higher plants can maintain hormonal balance andbe induced to secrete substantial amounts of organic acids (Xiang et al, 2019), which can act as a buffer, allowing plants to withstand environmental changes and preserve intracellular pH stability and ion balance (Yang et al, 2010; Li X Y et al, 2020).,andare involved in gibberellin biosynthesis and metabolism, along with the accumulation of indoleacetic acid and cytokinin broadly dispersed in root tips to cope with high-pH environments of saline-alkali stress (Xu et al, 2012). Ubder NaHCO3stress, the proton pump H+-ATPase may cause organic acid secretion from roots (Guo et al, 2018).is also involved in pH homeostasis, which is crucial for saline-alkali tolerance (Bassil et al, 2012). Similarly,andplay an essential role in K+and pH homeostasis in(Wang L G et al, 2015).

Chlorophyll content disruption

Soil saline and alkali stresses cause plants to absorb a large amount of Na+and Cl−,and inhibit the absorption of K+, Ca2+and Mg2+, and the ion imbalance leads to the accelerated chlorophyll degradation and the reduction of chlorophyll content (Guo et al, 2019). Saline-alkali stress disrupts the cellular integrity and usual functioning in rice, and destroys the thylakoid membrane structure,which further makes the stack of thylakoid membrane lose. As the degree of saline-alkali stress increases, the thylakoid and grana’s injury severity also increases (Wang et al, 2013). In addition, the lamellar structure is also evacuated or even collapsed to this stress that affects chlorophyll synthesis. Notably, a high pH level with saline stress declines the contents of chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b in rice plants.

Nitrogen metabolism

The adaptation process in saline-alkali medium is carried out through ion transport, compartmentalization, compatible solute synthesis followed by accumulation and nitrogen metabolism. The lack of external H+caused by saline-alkali stress weakens NO3−uptake. A high pH in roots leads to higher exchangeable Na+(Horie et al, 2012) and limits assimilation or uptake of NO3−(Wang et al, 2011; Wang H et al, 2012a), making saline-alkali stress more harmful to plants than salt stress alone. NO3−uptake is mediated by an H+/NO3−symport mechanism, which relies on the transmembrane H+gradient (Crawford and Glass, 1998), andis critical for long-distance nitrate transport from root to shoot through xylem parenchyma when nitrate supply is limited (Tang et al, 2012).The nitrate transporter genesandaccumulate NO3−in old leaves and are up-regulated by alkali stress, and NO3−deficiency in young leaves reduces theexpression. The subsequent deficiency of NH4+influences the down-regulation ofandin young leaves (Wang H et al, 2012a, b). At the same time,hinders NO3−transport in the vascular transport system in rice (Li et al, 2015). The lack of external H+during saline-alkali stress may reduce the exchange activity of the Na+/H+antiport on the root plasma membrane, thereby lowering Na+exclusion into the rhizosphere and increasingNa+buildup, even to hazardous levels. The excess of Na+and Cl−also changes the pathway of NH4+assimilation in old leaves of salt-stressed rice plants (Wang H et al, 2012b). Thus, the decreased Na+exclusion and NO3−uptake are the basis of saline-alkali stress injury (Wang H et al, 2015).regulates the root development in a NO3−-dependent manner and modulates salt tolerance in rice (Chen et al, 2018). Xu et al (2016) indicated that in salinity stress, nitrogen metabolism is accelerated and rearranged to synthesize more amino acids as the compatible solute to cope with unfavorable conditions.

Molecular mechanisms

Signal transduction pathway

Plant induces osmotic and ionic signals at the cellular level under saline-alkali stress, which initiates ionic homeostasis followed by osmotic adjustment to curb the severe adverse effect of saline-alkali stress. Various signaling molecules such as phospholipids, hormones, and Ca2+regulate stress signaling.encodes calcineurin B-like protein (CBL) and interacts with CIPK, and the activation of the kinase activity of SOS2/OsCIPK24 byis in a Ca2+dependent manner (Halfter et al, 2000; Liu et al, 2000). Stress causes Ca2+spiking, which activates the SOS3-SOS2 protein kinase complex, phosphorylating the plasma membrane Na+/H+antiporterunder sodic stress (Kumar et al, 2013; El Mahi et al, 2019). In rice, OsDMI,3, a Ca2+calmodulin-dependent protein kinase, regulatesand PM-H+-ATPase genesand,which enhance the saline-alkali tolerance in root growth by modulating the Na+and H+influx from NaHCO3(Ni et al, 2020).also activates tonoplast Na+/H+antiporter, sequestering Na+into the vacuole by NHX1 (Assaha et al, 2017). Furthermore, OsNHX genes,,,and, regulate the compartmentalization of Na+and K+that accumulates in the cytoplasm to increase salt-stressed tissues in rice (Fukuda et al, 2011). Some protein kinase SPKSs interact strongly with ABI2 whereas others interact preferentially with ABI1. The interaction between SOS2 and ABI2 is disrupted by the abi2-1 mutation, resulting in increased tolerance to salt shock (Ohta et al, 2003)(Fig. 3). CAX1 (H+/Ca2+antiporter) is an additional target for SOS2 activity restoring cytosolic Ca2+homeostasis (Martínez-Atienza et al, 2007). OsCBL4 (SOS3) is a unique Ca2+-binding protein with an N-myristoylation signature sequence required for SOS3 function in plant salt tolerance(Ishitani et al, 2000). SOS3 and SOS2 complex negatively regulates the activity of AtHKT1,a salt tolerance determinant that controls Na+entry and high-affinity K+uptakeeven in rice(Horie et al, 2006), and also exhibits a rhythmic and diurnal expression pattern (Soni et al, 2013). In,encodes a pyridoxal (PL) kinase involved in the synthesis of PL-5-phosphate, which regulates ion channels and transporters and aids in maintaining Na+and K+homeostasis (Shi and Zhu, 2002).

ABA has long been considered a signaling molecule, and ABA biosynthetic genes seem to be regulated by stress-induced Ca2+-dependent phosphorylation and its signaling pathways in rice (Du et al, 2010; Saeng-ngam et al, 2012). Overexpression ofleads to the accumulation of ABA and tolerance to salt stress due to encoding an ABA biosynthetic β-carotene hydrolase and a Ca2+-binding calmodulin in rice (Du et al, 2010; Kumar et al, 2013). In,interacts with ABA, and scavenges ROS by stimulating the antioxidant system, leading to an increase in stress-related gene expressions and thus contributing to saline-alkali tolerance (Acet and Kadıoğlu, 2020). In rice, OsRBOHsareinduced in ROS accumulation at the plasma membrane, which is scavenged or reduced byand regulates tolerance to saline-alkali stress (Liu X L et al, 2022)Moreover, Mahajan et al (2008) reported thatalso plays a key role in the maintenance of cell growth in plants under salt stress.

Hossain et al (2010)observed that, a member of bZIP genes, is up-regulated in salt-sensitive cultivar when exposed to long-term salinity. Similarly,,,,,andalso regulate the expression of stress-related genes in response to abiotic stresses in saline-alkali tolerance in rice (Nutan et al, 2020)., belonging to glutathione S-transferase (GST) gene family, reduces sensitivity towards plant hormones, auxin and ABA, and regulates saline-alkali stress (Sharma et al, 2014).andare ABA-mediated responsive genes that have been cloned (Fang et al, 2010; Zheng et al, 2014), which show enhanced salt tolerance in rice at the seedling stage of rice. As a negative regulator of stomatal closure via ABA-mediated signaling,plays a key role in plant tolerance to osmotic stress (Li et al, 2013). Among many DREB-homologous reported genes,andare positive regulators for high salinity stress responses through ABA-dependent signaling transduction pathways (Jaffar et al, 2016), and genes derived from rice andare more effective for salt tolerance (Datta et al, 2012).

Transcription factor (TF) expression

TFs are involved in stimulus signals and regulation of genes by receiving upstream signals and binding to their corresponding-regulatory sequences. Expression levels of many TFs are modified significantly in response to saline-alkali stress, and some of themare involved in rice (Table 1). These TFs belonging to AP2/ERF, HD-zip/bZIP, MYC/MYB, WRKY and NAC families, show response to saline-alkali stress.

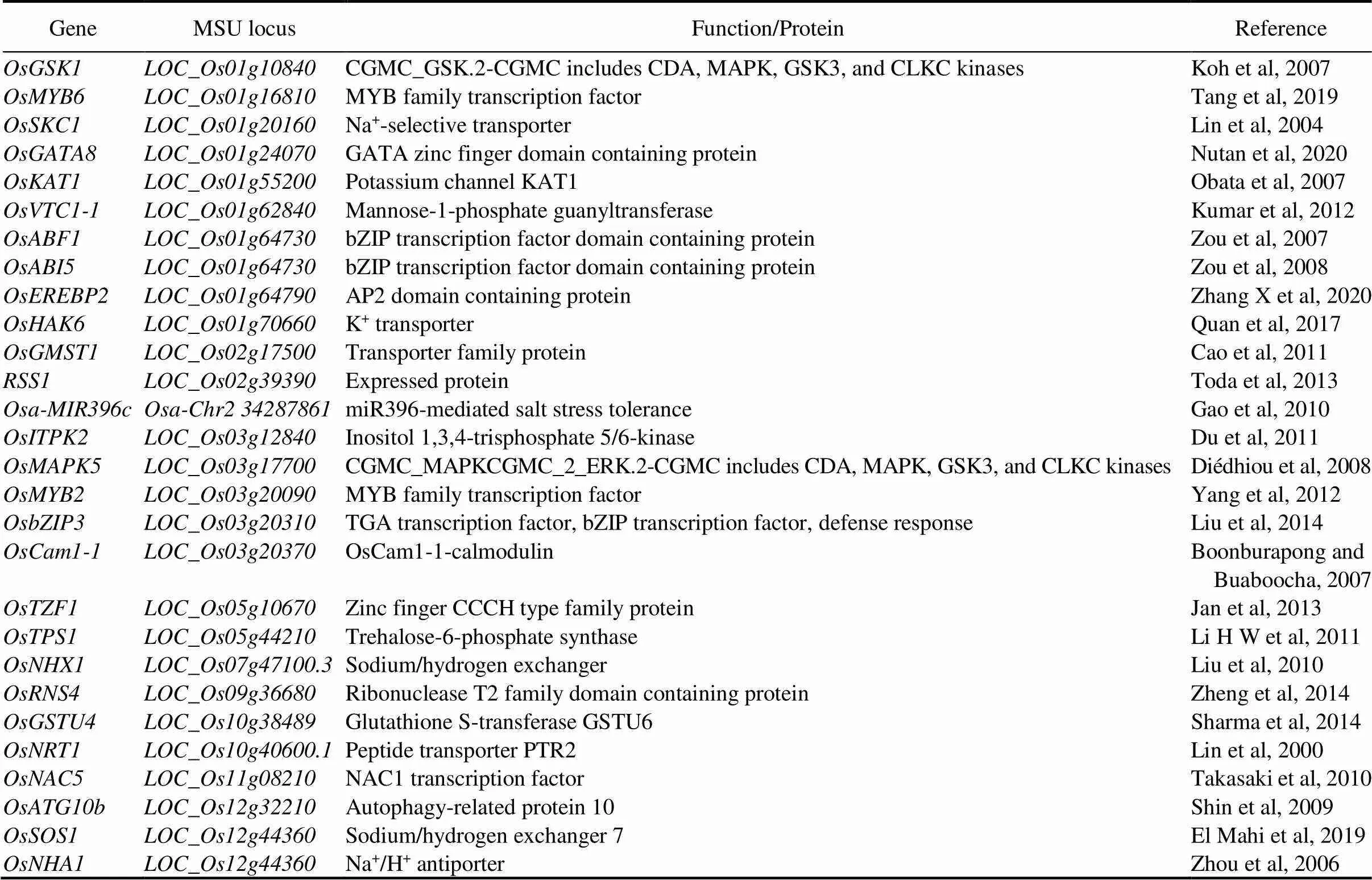

Table 1. Some candidate genes/transcription factors/proteins are responsive to saline-alkali stress and their functions.

AP2/ERF is a large TF family characteristic with at least one or two highly conserved DNA-binding domains, which regulate plant growth, development, and response to abiotic stress (Xie et al, 2019). Nucleus localizedencodes an AP2/ERF-type TF that can bind to DREB and is also involved in ABA signal transduction and salinity response by decreasing the Na+/K+ratio and maintaining cellular redox homeostasis (Wang et al, 2020). Moreover, ABA increases relative water content and decreases cell membrane injury degree and Na+/K+ratios under saline-alkaline stress(Wei et al, 2015)., which encodes an ERF TF, improves rice salt stress tolerance by enhancing redox homeostasis and membrane stability (Wang et al, 2021).

Fig. 3. Saline-alkali stress signaling pathway and adaptation mechanisms [modified from Shi and Zhu (2002)and Chen et al (2021)].

ABA, Abscisic acid; ABA8ox, ABA-8′- hydroxylase; ABI1, Abscisic acid insensitive 1; ABI2, Abscisic acid insensitive 2; ADP, Adenosine diphosphate; AKT1, Arabidopsis K+transporter 1; AP2, APETALA2; ATP, Adenosine triphosphate; BOR1-4, Boron transporter 1-4; bZIP, Basic- domain leucine zipper; CAX1a, Ca2+/H+exchanger; CBL4, Calcineurin B-like protein; CIPK24, CBL- interacting protein kinase 24; DMI3, Doesn’t make infections 3; GORK, Guard-cell outward rectifying K+channel; ATPase, ATP enzyme; HKT1, High affinity K+transporter; MYB, v-Myb avian myeloblastosis viral oncogene homolog; NAC, NAM, ATAF1/2 and CUC2; NHX, Na+/H+exchanger; PL kinase, Pyridoxal kinase; PLP, Pyridoxal-5-phosphate; RBOHs, Respiratory burst oxidase homologs; SKOR, Stelar K+outward rectifier; SOS1, Salt overly sensitive 1; SOS4, Salt overly sensitive 4; V-ATPase, Vacuolar-ATPase; V-PPase, Vacuolar H+-pyrophosphatase; ROS, Reactive oxygen species; PPi, Pyrophosphoric acid; Pi, Phosphoric acid.

bZIPs participate in bZIP transcriptional activation under bicarbonate-alkali stress, reduce the accumulation of MDA and increase POD and chlorophyll contents to improve salt-alkali tolerance (Wu et al, 2018).categorized as a bZIP transcription member contributes to multiple abiotic stress, including salinity (Das et al, 2019).is involved in ABA signaling pathways that improve oxidative stress tolerance, associated with saline-alkali stress tolerance in rice (Yang et al, 2010). AREB/ABF is a bZIP-type TF, and homologous genes of AREB/ABF are regulated by salt stress. OsABF1 and OsABF2 are positive regulators for abiotic stress responses and ABA-dependent signaling transduction pathways in rice (Hossain et al, 2010). Another bZIP TF OsGATA8 has contributed to multiple stress tolerance and seed development in rice (Nutan et al, 2020). OsZFP252, OsZFP179 and OsZFP182 are zinc finger protein TFs that enhance free proline and soluble sugars, which improve rice tolerance to salt stress, and upregulate the expression of stress-tolerant genes (Huang et al, 2012; Liu C T et al, 2022). OsEREBP2, the zinc-finger proteins DST, and DCA1 negatively affect rice salt tolerance by regulating the transcription of ROS scavenging genes (Cui et al, 2015).

Members of the MYB TF family show a significant change in alfalfa, and the expression of most MYB TFs is inclined to increase (Coskun et al, 2016). MYB family genes,,and, increase drought and salinity stress tolerance in rice (Xiong et al, 2014;Tang et al, 2019). In,enhances Ca2+buildup in leaves, and lowers oxidative damage, and improves membrane integrity by upregulating the expression of genes encoding POD, SOD and LEA, and reduces non-stomatal leaf water loss by positively modifying cutin deposition in leaves through overexpression of genes classed as cutin, suberin and wax production in salt stress (Zhang P et al, 2020).Overexpression ofin rice significantly improves tolerance to drought and salinity stresses by reducing water loss, lowering MDA content, and increasing proline content under stress conditions (Xiong et al, 2014).

The WRKY gene family is a TF group that plays important roles in many different response pathways to saline and alkali stresses (Li W X et al, 2020). In rice, overexpression ofenhances the expression of Ca2+-dependent protein kinase genesandto counteract salt stress (Tang, 2018).is phosphorylated by MAPK cascades, which improves osmotic tolerance of rice.,, andenhance the tolerance to salinity, osmotic and oxidative stresses in rice (Banerjee and Roychoudhury, 2015).

In response to salinity and alkali stresses, the plant-specific NAC TF family has garnered attention (Marques et al, 2017). Plant adaptation to environments with high salinity and alkalinity may be related to NAC factors by different patterns of action. Stress-related TFs such as,andare activated by(Sakuraba et al, 2015) and(Hong et al, 2016).(Takasaki et al, 2010),(Zheng et al, 2009) and(Shen et al, 2017) play a vital role in the salt stress response by transcriptionally increasing the expression of stress-inducible rice genes such asand.

Reduced proline accumulation, root volume, spikelet fertility, biomass and grain yield in rice are dependent on the expression level of kinase regulatory gene(), which belongs to the OsITPK family (Du et al, 2011). During the seed germination and seedling stages, OsCIPK31 and OsTZF1are involved in gene responses to high saline-alkali stress (Piao et al, 2010;Jan et al, 2013). In addition to protein-coding genes, miRNAs and RNAi have recently been revealed as major participants in plant stress responses.is also responsible for the significant transcript alterations by multiple TFs linked to the growth and development of rice under salt and alkali stresses (Gao et al, 2010).

Mapping and cloning of saline-alkali tolerance QTL in rice

There are wide variations in tolerance to saline-alkali stress among rice germplasms. Traditional cultivars are normally tolerant to a wide range of abiotic stresses (Yeo and Flowers, 1986). Efficient trait selection and screening are crucial for evaluating tolerance of genetic resources to saline-alkali and mining of saline-alkali responsive alleles.

Screening for saline-alkali tolerance

A simple mass screening technique should at least meet the requirements of exhibiting adequate genetic variability and the ability to easily handle a large population. Screening in the field is generally suggested, but it is not completely appropriate because homogenous stress can not manage effectively due to soil and environmental problems (Almeida et al, 2016). Saline-alkali tolerance at the seedling stage under hydroponic conditions is fast, easy to control, and well adapted to the high volume of material from breeding programs (Bhowmik et al, 2009). The hydroponics culture method ensures uniform stress with ample nutrients so that genotypic variances can be attributed to intrinsic differences intolerance. Yoshida culture-based technique has been extensively used for screening a large number of plant populations. To counter the adverse effects of Na+on other nutrients in Yoshida culture solution (Yoshida, 1976), a modified Yoshida solution is developed (Flowers and Yeo, 1981) and is considered the most appropriate for rice growth (Singh et al, 2009).

Rice seeds are usually sowed and grown on floats for a nutrient solution until 2- to 3-leaf stage, then the stress (0.8% NaCl for salt stress or 0.15% Na2CO3for alkali stress) is imposed before scoring or evident phenotypic conditions. The traits most commonly assessed include salinity-induced injuries, days to survival, Na+and K+uptake, and Na+and K+concentrations in various tissues and organs. Injuries can be measured by visual scales or survival rates, relative development, or biomass production of different organs in a population versus reference or saline/alkali versus control conditions over a period of time. Detailed screening procedures for different stages of rice have been proposed and discussed by Singh et al (2005). To timely monitor physiological response, screening techniques targeting individual mechanisms have yet to be proposed to enable dissecting the different plant reaction types (Damien et al, 2021). Electrical potential differences between the external solution and the root vacuoles were maintained to measure sodium exclusion, allowing the evaluation of 50–100 plants a day with image captured and analyzed by an equipment (Rajendran et al, 2009). Consider that the correlation of survival and visual assessment of salt damage has a limited link with physiological parameters,Yeo et al (1990) suggested using overall performance to determine the tolerant accessions for breeding programs.

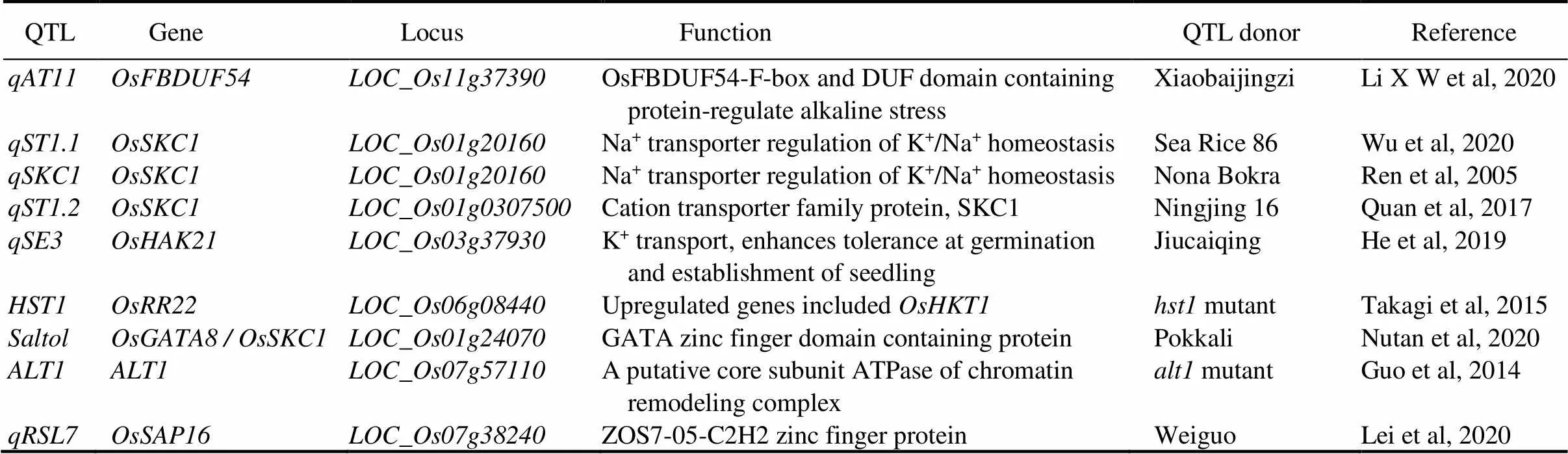

Table 2. Main-effect QTLs for saline-alkaline tolerance detected in rice populations.

Chr,Chromosome; PVE, Phenotypic variation explained by the QTL.

QTLs associated with saline-alkali tolerance

A large number of QTLs affecting saline-alkali tolerance have been identified at the rice germination and seedling stages using different morphological traits such as germination rate and germination index (Naveed et al, 2018), salt injury score, seedling height, and plant biomass at whole-plant level (Chen et al, 2019), and physiological indicators such as Na+and K+concentrations in shoots and roots (Lin et al, 2004), relative growth rate and transpiration rate (Al-Tamimi et al, 2016). A few QTLs are major-effective and worthy of further fine-mapping or cloning (Table 2). Using an F2:3population derived from a tolerantlandrace Nona Bokra and a susceptibleKoshihikari, several QTLs controlling salt tolerance have been identified, including major QTLs for shoot K+concentration on chromosome 1 () and shoot Na+concentration on chromosome 7 () (Lin et al, 2004). Another QTL associated with the Na+/K+ratio and salinity tolerance at seedling-stage, named, has been identified on chromosome 1 in a recombinant inbred line (RIL) population betweenvarieties IR29 and Pokkali, explaining 43% of the variation for Na+/K+ratio in shoot (Bonilla et al, 2002). However, theidentified from Pokkali does not provide a high degree of salt tolerance based on overall visual performances at the seedling stage (Thomson et al, 2010;Alam et al, 2011). Chen T X et al (2020) identifiedfor relative shoot K+concentration,for shoot Na+concentration,for K+/Na+ratio in shoots,for root Na+concentration, andfor K+/Na+ratio in shoots, which are located within thesegment (11.0‒12.2 Mb) on chromosome 1 (Thomson et al, 2010), and the nearest bin marker Bin1 (11.35–11.50) harbors thegene (11.46 Mb) (Ren et al, 2005; Mohammadi et al, 2013). Other newly identified QTLs from Pokkali, including,andon chromosome 1,are co-localized with(39.5 Mb) detected in a set of introgression lines of Pokkali as a donor (de Leon et al, 2017).(40.3 Mb), from a salt-tolerant Dongxiang wild rice (Quan et al, 2017), is adjacent to(40.8 Mb),(40.9 Mb) and(41.1 Mb) which encodes high-affinity potassium transporters mediating K+uptake (Horie et al, 2011). Moreover,for seedling salinity tolerance identified from Sea Rice 86 is located within theregion with the same amino acid sequence of Nona Bokra (Wu et al, 2020).is detected and subsequently isolated from a Chinese landrace Jiucaiqing (He et al, 2019).positioning on 15.0 Mb region of chromosome 3 is associated with ion homeostasis under saline-alkali stress (Li et al, 2019). A salt-tolerance-specific QTLencoding tyrosine phosphatase family protein has been fine-mapped to a 65.9-kb region on chromosome 2 (Zeng et al, 2021), in which three possible candidate genesare included.Among them,exclusively expressesand influencesgermination rate, which delineates the genetic basis of germination (Li M et al, 2011).

There are limited reports on QTL mapping for salt tolerance during the reproductive stage compared with the seedling stage. A QTL for Na+uptake and Na+/K+ratio in the shoot at the reproductive stage is located on chromosome 1 at a different position to(Hossain et al, 2015). Three QTLs on chromosome 1 at positions 32.3, 35.0 and 39.5 Mb have been identified for grain yield per plant under salinity stress from a salinity-tolerantrice variety CSR11 (Tiwari et al, 2016). Two QTLs,for spikelet degeneration andfor spikelet sterility, are mapped on chromosome 2, accounting for 34.4% and 38.8% of the phenotypic variances, respectively, with tolerance alleles from Pokkali (Chattopadhyay et al, 2021).

QTLs mapped in bi-parental segregating populations are insufficient to reveal the genetic variations in salt tolerance among rice germplasms. Recently, the natural population has been widely used in QTL mapping with significant advantages over the bi-parental populations, offering a powerful strategy for dissecting the genetic architecture of various complex traits and identifying allelic variations of candidate genes in rice (Kumar et al, 2015).affecting Na+/K+ratio at the rice seedling stage is also responsible for balancing Na+/K+ratio at the reproductive stage as revealed by a genome-wideassociated study (GWAS) (Kumar et al, 2015)., which controls root Na+/K+ratio and root Na+content under moderate salinity stress, has been identified in a 575-kb region on chromosome 4 (Campbell et al, 2017). Two auxin-biosynthesis genes are identified as candidate genes for salinity tolerance based on GWAS of 478 rice accessions at the seed germination stage (Cui et al, 2018). A total of 15 promising candidate genes including 5 known genes (,,,and) and 10 novel genes are associated with grain yield and its related traits under saline stress conditions (Liu et al, 2019). A QTL for salt tolerance on chromosome 1 (surrounding 40 Mb) is detected in diverse rice species including cultivars, landraces and wild rice (Chen et al, 2019).

QTL cloning for saline-alkali tolerance

Following pioneering work, several QTLs for saline- alkali tolerance in rice have been cloned (Yano et al, 2000). A gene underpinning the primary QTL on chromosome 1 for salinity tolerance has been isolated via map-based cloning (Ren et al, 2005). The() gene encodes a sodium transporter of HKT type (the favorable allele coming from Nona Bokra). Besides this gene, fine mapping of the same region on chromosome 1 reveals the presence of a cluster of QTLs (Ul Haq et al, 2010). Another QTLassociates with the shoot Na+/K+ratio at the seedling stage has been identified from a salt-tolerant landrace Pokkali (Bonilla et al, 2002).is the functional gene underlying thesegment (Thomson et al, 2010). Transcript abundance analysis within this QTL using corresponding genes for contrasting rice genotypes revealed that transcripts and encoding of the TFs and signaling-related genes are constitutively higher in the landraces than those in a salt-sensitive high-yielding rice cultivar IR64. In rice, histone-gene binding protein (OsHBP1b) and zinc-finger transcription factor (OsGATA8), both found in theregion regulating the expression of several genes, are involved in chlorophyll biosynthesis, ion homeostasis, and ROS scavenging, as well as play a key role in seedling salt tolerance (Das et al, 2019; Nutan et al, 2020).

Table 3. Some cloned and fine-mapped genes/QTLs for saline-alkali tolerance in rice.

has been discovered in theregion of SeaRice 86 for seedling salinity tolerance, and the amino acid sequence ofin Sea Rice 86 and Nona Bokra is identical (Wu et al, 2020). The high-affinity K+uptake transporter (OsHAK21) is encoded by the QTLthat is identified from a Chinese landrace Jiucaiqing, facilitating seed germination and seedling establishment under salinity stress (He et al, 2019) (Table 3). Salt tolerance genehas been cloned by the MutMap method from the mutant(Takagi et al, 2015).on chromosome 11 bearing F-box and DUF domaincontaining protein enhances the tolerance to alkaline, which is identified through linkage mapping and GWAS (Li X W et al, 2020). Another QTL,,has been cloned and the candidate generesponsive to abiotic stress tolerance is from Weiguo with 24.90% of phenotypic variations (Lei et al, 2020). The alkaline tolerant geneis only cloned by the map-based cloning method from the mutant, which negatively functions in alkaline tolerance mainly through the defense against oxidative damage (Guo et al, 2014).

Expression of QTLs under saline-alkali conditions

QTLs for saline-alkali stress tolerance and their expression are so complicated in rice that even tolerance to one developmental stage does not correlate with tolerance at other developmental stages (Tal, 1985). QTLs identified for saline-alkali tolerance at the germination stage are different from those at the seedling stage, indicating that different genes or physiological mechanisms regulate saline-alkali tolerance at the two stages (Cheng et al, 2008). Sometimes, salt tolerance is overlapped by saline-alkali tolerance (Lv et al, 2013). Therefore, specific ontogenetic stages throughout the plant life cycle should be evaluated separately, which can simplify the nature of complex traits and help in understanding the genetic control of stress tolerance and improving plant tolerance. Furthermore, because of the environment effects on gene expression, QTLs are environmental and populationspecific (Cheng et al, 2012).

Modern approaches of breeding for saline-alkali tolerance in rice

Nearly half of all arable lands in the world will be under salinization by 2050 (Butcher et al, 2016), raising a huge threat to sustainable agriculture development and food security. Developing rice varieties with high salt tolerance is the most efficient approach for copying with soil salinity (Schroeder et al, 2013). Most of the varieties have been developed through conventional breeding, which is a time-consuming procedure (Qin et al, 2020), and the level of tolerance is not as expected. From the early of the century, breeders preferred this strategy for obtaining better Na+exclusion or lower tissue Na+/K+ratio for saline-alkali tolerance, keeping aside the other important mechanisms and attaining a similar level of tolerance as the donor (Shahbaz and Ashraf, 2013). In the recent decades, molecular genetics and genome breeding have been rapidly developed, making it possible to efficiently mine favorable alleles for saline-alkali tolerance and introgress them into elite rice varieties by integrated breeding approaches (Fig. 4).

Marker-assisted breeding

Marker-assisted selection (MAS) is the most promising and successful method for developing new salt-tolerant rice lines (Singh et al, 2016). The implication of this technique in the modern breeding programs is that the breeding cycle can be shortened by allowing for the selection of plants with the target genes at the early growth stages. Marker-assisted backcross (MABC) breeding is faster and more precise to introgress/transfer linked genes for salinity tolerance. This allows selecting plants in each breeding season to confirm the introgressed target genes and recovery of the parental genome and reduce linkage drag. Nowadays, MAS and MABC have been usually used in rice saline-alkali tolerant breeding (Ashraf and Foolad, 2013)., a favorable QTL that contains a TF,, responsible for shoot Na+/K+homeostasis underlying salt tolerance of Pokkali, has been successfully introgressed into commercial varieties using MABC (Qin et al, 2020). Many attempts have been made to introgressinto two high-yielding commercial rice varieties, BR11 and BR28,by the Bangladesh Rice Research Institute (Rahman et al, 2013). A MABC strategy was undertaken to transfer favorable alleles offrom FL478 into BT7, and the rice salt tolerance has been successfully improved without penalizing agronomic performance (Linh et al, 2012). Similarly,, found in the salinity-tolerant mutant,has been introgressed to cultivars Hitomebore and Yukinko-mai, and high-yielding cultivars Kaijin and YNU31-2-4 have been developed, respectively, by MABC with salinity tolerance at both seedling and reproductive stages (Takagi et al, 2015; Rana et al, 2019). Alkaline tolerant QTLis favorable for alkaline tolerance (Qin et al, 2020), which will be the resource for the future breeding program for saline-alkali tolerance variety development. Using the F4population derived from a cross between two selected introgression lines, six mostly homozygous promising high-yielding lines have been developed by MAS with significantly improved salt tolerance and grain yield under optimal or saline conditions, and three QTLs affecting salt injury score and leaf chlorophyll content have been identified (Pang et al, 2017).

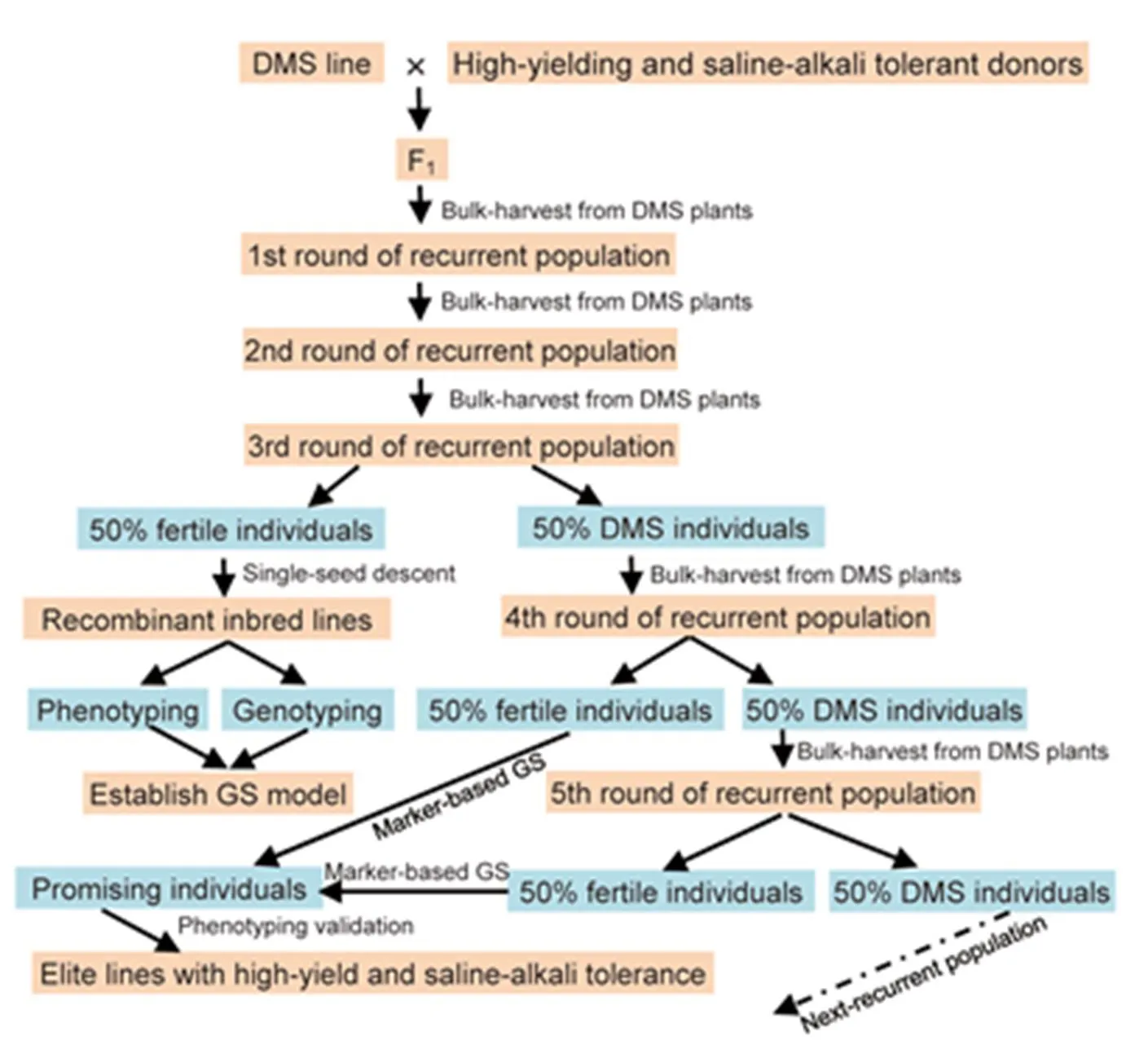

Genomic selection

Genomic selection (GS) is a breeding method that makes use of genome-wide DNA marker data to improve the efficiency of breeding for quantitative traits. In GS, individuals with superior breeding values are identified and selected based on prediction models built by correlating phenotype and genotype in a breeding population of interest. The potential of GS to improve rice breeding efficiency has been evidenced (Xu et al, 2014; Spindel et al, 2015). However, efforts to implement GS in rice breeding are still limited, particularly as compared to other major grain crops such as maize and wheat.The predictive ability of GS largely depends on relationship between training population and breeding population, and more accurate prediction can be achieved for genetically similar populations (Xu et al, 2021). Here, we introduced a new GS strategy, dominant male sterility (DMS) gene-based GS (Fig. 5). In this case, a molecular recurrent selection (MRS) population can be established using a set of high-yielding varieties and saline-alkali tolerant varieties. Random mating between varieties will be facilitated by the DMS gene in each cycle of selection. After three rounds of recombination, seeds will be bulk-harvested from 50% fertile individuals for developing RILs by single-seed descent. The RILs could be used as a training population to establish prediction model based on genome-wide DNA marker and phenotype of saline-alkali tolerance. Desirable recombinant multi-locus genotypes with significantly improved saline-alkali tolerance will be identified by marker-based GS in the following cycle in the fertile populations. The selected progeny incorporating the MRS population of next cycle together with modifying the prediction model will greatly improve predictive ability. Close relationship between the training population and the selected population will ensure effectiveness of GS in the MRS population. As expected, promising lines with high-level saline-alkali tolerance will be selected by GS after multiple recombination.

Fig. 4. Schematic diagram of saline-alkali stress tolerance mechanism and development of stress-tolerant varieties.

Modified from Fang et al (2021). GWAS,Genome-wide association study.

Transgenic approach

The transgenic approach is another possible way of achieving saline-alkali tolerance in rice. This approach has primarily been performed on single genes of tolerance mechanisms that significantly improve salinity tolerance at the reproductive stage (Anwar and Kim, 2020). Under saline-alkali treatments, transgenic rice accumulates Na+/H+in both shoots and roots, and then Na+/H+antiporter gene family of tonoplast in many plants can improve salt tolerance of rice. Ohta et al (2002) transferred and overexpressed Na+/H+antiporter geneoftonoplast from halophytein rice, thus improved salt tolerance of transgenic rice. Anoop and Gupta (2003) successfully transferredgene into rice and found that transgenic rice shows better root growth and higher biomass. Transformation ofimproves proline content up to 2–6 times in transgenic rice plants, and the rice plants can survive four weeks under 200 mmol/L NaCl (Karthikeyan et al, 2011). Under salt stress, a lot of GB will be accumulated in rice cells to maintain the balance of osmosis. The synthesis of GB is catalyzed by choline monooxygenase (CMO) and betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase (BADH). Shirasawa et al (2006) transferred thegene into rice from spinach byand found transgenic rice has increased GB content, thus improving salt tolerance. Similarly, Guo et al (1997) transferred thegene into Zhonghua 8 from spinach by particle bombardment, resulting in a significant improvement of salt tolerance in transgenic rice plants. Ca2+signal plays a significant role in response to many abiotic stresses in rice. Therefore, it is possible to improve salt tolerance for crops by utilizing regulatory factors in the conduction of the Ca2+signals (Wang et al, 2008).from barley has been introduced into rice, and the transgenic rice plants show a significant increase in their tolerance to water and salt stresses (Xu et al, 2008). Asano et al (2012) transferredinto rice, resulting in higher salt tolerance in transgenic rice, whereis a protein kinase gene dependent on Ca2+and the involved reaction of ABA to salt stress.encodes a Na+-selective transporter that maintains K+/Na+homeostasis under salt stress.positively regulates the expression ofand results in tolerance to saline-alkali stress (Liu et al, 2021).

Fig. 5.Molecular recurrent selection system for improving saline-alkali tolerance using dominant male sterility (DMS) gene-based genomic selection (GS) and high-yielding and saline-alkali tolerant donors.

In a word, the response of rice to salt stress is controlled and regulated by multiple factors, which involves many changes in physiology, biochemistry, and cells. Based on progress in molecular mechanisms of salt tolerance in rice, it will be promising to improve salt tolerance by the transformation of multiple salt tolerance genes.

Genome editing technique

Genome editing technique has revolutionized plant genomics for improving crop plants’ characteristics against abiotic stress. CRISPR/Cas9 technology has been utilized effectively in major crops and model plants for its reliability, flexibility, and great perfection (Li J Y et al, 2017). In rice, genome editing is combined with innovation to create new varieties with greater yield and quality and high resistance to abiotic and biotic stresses. The emerging CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing technology, which considers knockout, base editing and allele exchange, is an alternative approach for accelerating crop breeding. Such technologies are beneficial when favorable alleles associated with the species have been identified and characterized, as is the case for salt tolerance (Ismail and Horie, 2017). This technique has improved rice salt tolerance by knocking outor(Zhang et al, 2018; Zhang et al, 2019). Zhou et al (2017) used CRISPR-Cas9-based genome editing to obtain mutants of miRNA genes (and) and miRNA gene families (and) in rice and revealed a positive regulator of rice salt stress tolerance,. CRISPR/Cas9 has been used to generate mutants and proved that the GT-1 element directly controls the salt response of OsRAV2 (Duan et al, 2016) andplays a vital role in ABA signal responses and salt tolerance in rice (Zhang X et al, 2020). This technology also offers an effective tool for the identification and use of miRNAs regulating stress tolerance. With the rapid development of functional genomics, and the identification and characterization of other important genes, genome editing will provide more powerful and efficient opportunities for improving the salt tolerance of crops.

Conclusion and future prospect

In the past decades, high yield, better grain quality, multiple disease and insect resistances were major objectives of rice breeding, resulting that tolerance to saline-alkalinity lags behind. Most of the modern rice cultivars are highly or moderately sensitive to saline-alkali stress and thus do not perform well under field saline-alkali conditions. Limited progress has been made in developing salt-tolerance rice varieties due to the lack of both genetic resources with high salinity tolerance and reliable salinity-tolerance genes with large effects. Future studies should also focus on mining genes/QTLs from diverse genetic resources such as 3010 (3K) re-sequenced germplasms (Wang et al, 2018), particularly wild rice relatives, to retrieve salinity tolerance traits lost during domestication. Luckily, saline-alkali tolerant genetic resources have been identified and utilized for breeding improved saline-alkali tolerant rice varieties. Moreover, as more molecular markers are becoming available, many major and minor QTLs are identified for saline-alkali tolerance. Using high throughput SNP genotypic and gcHap data of 3K germplasms (Zhang et al, 2021), we can deeply mine favorable alleles/haplotypes for those previously cloned salt tolerance genes including TFs via map-based cloning and reverse genetic approach. Thus, it may be more effective to carry out accurate breeding for saline-alkali tolerance by MAS and gene-editing.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Key-Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province, China (Grant No. 2020B020219004), the Hainan Yazhou Bay Seed Lab (Grant No. B21HJ0216), and the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program and the Cooperation and Innovation Mission, China (Grant No. CAAS-ZDXT202001). We are grateful to Dr. Muhiuddin Faruquee and Song Mei for their supports during the preparation of this manuscript.

Acet T, Kadıoğlu A. 2020.gene-abscisic acid crosstalk and their interaction with antioxidant system inunder salt stress., 26(9): 1831–1845.

Al-Tamimi N, Brien C, Oakey H, Berger B, Saade S, Ho Y S, Schmöckel S M, Tester M, Negrão S. 2016. Salinity tolerance loci revealed in rice using high-throughput non-invasive phenotyping., 7: 13342.

Alam R, Sazzadur Rahman M, Seraj Z I, Thomson M J, Ismail A M, Tumimbang-Raiz E, Gregorio G B. 2011. Investigation of seedling-stage salinity tolerance QTLs using backcross lines derived fromL. Pokkali., 130(4): 430–437.

Alhendawi R A, Römheld V, Kirkby E A, Marschner H. 1997. Influence of increasing bicarbonate concentrations on plant growth, organic acid accumulation in roots and iron uptake by barley, sorghum, and maize., 20(12): 1731–1753.

Almeida D M, Almadanim M C, Lourenço T, Abreu I A, Saibo N J M, Oliveira M M. 2016. Screening for abiotic stress tolerance in rice: Salt, cold, and drought., 1398: 155–182.

Anoop N, Gupta A K. 2003. Transgenicrice cv IR-50 over-expressingΔ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase cDNA shows tolerance to high salt., 12(2): 109–116.

Anwar A, Kim J K. 2020. Transgenic breeding approaches for improving abiotic stress tolerance: Recent progress and future perspectives., 21(8): 2695.

Asano T, Hayashi N, Kikuchi S, Ohsugi R. 2012. CDPK-mediated abiotic stress signaling., 7(7): 817–821.

Ashraf M, Harris P J C. 2004. Potential biochemical indicators of salinity tolerance in plants., 166(1): 3–16.

Ashraf M, Foolad M R. 2013. Crop breeding for salt tolerance in the era of molecular markers and marker-assisted selection., 132(1): 10–20.

Assaha D V M, Ueda A, Saneoka H, Al-Yahyai R, Yaish M W. 2017. The role of Na+and K+transporters in salt stress adaptation in glycophytes., 8: 509.

Banerjee A, Roychoudhury A. 2015. WRKY proteins: Signaling and regulation of expression during abiotic stress responses., 2015: 807560.

Bassil E, Coku A, Blumwald E. 2012. Cellular ion homeostasis: Emerging roles of intracellular NHX Na+/H+antiporters in plant growth and development., 63(16): 5727–5740.

Bhatt T, Sharma A, Puri S, Minhas A P. 2020. Salt tolerance mechanisms and approaches: Future scope of halotolerant genes and rice landraces., 27(5): 368–383.

Bhowmik S, Titov S, Islam M, Siddika A, Sultana S, Haque M S. 2009. Phenotypic and genotypic screening of rice genotypes at seedling stage for salt tolerance., 8: 6490–6494.

Bonilla P, Dvorak J, MacKill D, Deal K, Gregorio G. 2002. RFLP and SSLP mapping of salinity tolerance genes in chromosome 1 of rice (L.) using recombinant inbred lines., 65(1): 68–76.

Boonburapong B, Buaboocha T. 2007. Genome-wide identification and analyses of the rice calmodulin and related potential calcium sensor proteins., 7: 4.

Butcher K, Wick A F, deSutter T, Chatterjee A, Harmon J. 2016. Soil salinity: A threat to global food security., 108(6): 2189–2200.

Campbell M T, Bandillo N, Al Shiblawi F R A, Sharma S, Liu K, Du Q, Schmitz A J, Zhang C, Véry A A, Lorenz A J, Walia H. 2017. Allelic variants ofunderlie the divergence betweenandsubspecies of rice () for root sodium content., 13(6): e1006823.

Cao H, Guo S Y, Xu Y Y, Jiang K, Jones A M, Chong K. 2011. Reduced expression of a gene encoding a Golgi localized monosaccharide transporter (OsGMST1) confers hypersensitivity to salt in rice ()., 62(13): 4595–4604.

Chattopadhyay K, Mohanty S K, Vijayan J, Marndi B C, Sarkar A, Molla K A, Chakraborty K, Ray S, Sarkar R K. 2021. Genetic dissection of component traits for salinity tolerance at reproductive stage in rice., 39(2): 386–402.

Cha-Um S, Supaibulwatana K, Kirdmanee C. 2007. Glycinebetaine accumulation, physiological characterizations and growth efficiency in salt-tolerant and salt-sensitive lines ofrice (L. ssp.) in response to salt stress., 193(3): 157–166.

Chen G, Hu J, Dong L L, Zeng D L, Guo L B, Zhang G H, Zhu L, Qian Q. 2019. The tolerance of salinity in rice requires the presence of a functional copy of., 10(1): 17.

Chen H L, Xu N, Wu Q, Yu B, Chu Y L, Li X X, Huang J L, Jin L. 2018.regulates the root development in a NO3–: Dependent manner and modulates the salt tolerance in rice (L.)., 277: 20–32.

Chen L N, Yin H X, Xu J, Liu X J. 2011. Enhanced antioxidative responses of a salt-resistant wheat cultivar facilitate its adaptation to salt stress., 10: 16884–16886.

Chen T X, Zhu Y J, Chen K, Shen C C, Zhao X Q, Shabala S, Shabala L, Meinke H, Venkataraman G, Chen Z H, Xu J L, Zhou M X. 2020. Identification of new QTL for salt tolerance from rice variety Pokkali., 206(2): 202–213.

Chen T X, Shabala S, Niu Y N, Chen Z H, Shabala L, Meinke H, Venkataraman G, Pareek A, Xu J L, Zhou M X. 2021. Molecular mechanisms of salinity tolerance in rice., 9(3): 506–520.

Chen W C, Cui P J, Sun H Y, Guo W Q, Yang C W, Jin H, Fang B, Shi D C. 2009. Comparative effects of salt and alkali stresses on organic acid accumulation and ionic balance of seabuckthorn (L.)., 30(3): 351–358.

Chen Y H, Shao Q L, Li F F, Lv X Q, Huang X, Tang H J, Dong S N, Zhang H S, Huang J. 2020. A little membrane protein with 54 amino acids confers salt tolerance in rice (L.)., 42: 87.

Cheng H T, Jiang H, Xue D W, Guo L B, Zeng D L, Zhang G H, Qian Q. 2008. Mapping of QTL underlying tolerance to alkali at germination and early seedling stages in rice., 34(10): 1719–1727. (in Chinese with English abstract)

Cheng L R, Wang Y, Meng L J, Hu X, Cui Y R, Sun Y, Zhu L H, Ali J, Xu J L, Li Z K. 2012. Identification of salt-tolerant QTLs with strong genetic background effect using two sets of reciprocal introgression lines in rice., 55(1): 45–55.

Chuamnakthong S, Nampei M, Ueda A. 2019. Characterization of Na+exclusion mechanism in rice under saline-alkaline stress conditions., 287: 110171.

Coskun D, Britto D T, Kochian L V, Kronzucker H J. 2016. How high do ion fluxes go? A re-evaluation of the two-mechanism model of K+transport in plant roots., 243: 96–104.

Crawford N M, Glass A D M. 1998. Molecular and physiological aspects of nitrate uptake in plants., 3(10): 389–395.

Cui L G, Shan J X, Shi M, Gao J P, Lin H X. 2015. DCA1 acts as a transcriptional co-activator of DST and contributes to drought and salt tolerance in rice., 11(10): e1005617.

Cui Y R, Zhang F, Zhou Y L. 2018. The application of multi-locus GWAS for the detection of salt-tolerance loci in rice., 9: 1464.

Damien J, Patten A H, Ismail A. 2021. Phenotyping Protocols for Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Rice. Manila, the Philippines: International Rice Research Institute(IRRI).

Das P, Lakra N, Nutan K K, Singla-Pareek S L, Pareek A. 2019. A unique bZIP transcription factor imparting multiple stress tolerance in rice., 12(1): 58.

Datta K, Baisakh N, Ganguly M, Krishnan S, Shinozaki K Y, Datta S K. 2012. Overexpression ofand rice stress genes’ inducible transcription factor confers drought and salinity tolerance to rice., 10(5): 579–586.

de Leon T B, Linscombe S, Subudhi P K. 2017. Identification and validation of QTLs for seedling salinity tolerance in introgression lines of a salt tolerant rice landrace ‘Pokkali’., 12(4): e0175361.

Diédhiou C J, Golldack D. 2006. Salt-dependent regulation of chloride channel transcripts in rice., 170(4): 793–800.

Diédhiou C J, Popova O V, Dietz K J, Golldack D. 2008. The SNF1-type serine-threonine protein kinase SAPK4 regulates stress-responsive gene expression in rice., 8: 49.

Dong N Q, Sun Y W, Guo T, Shi C L, Zhang Y M, Kan Y, Xiang Y H, Zhang H, Yang Y B, Li Y C, Zhao H Y, Yu H X, Lu Z Q, Wang Y, Ye W W, Shan J X, Lin H X. 2020. UDP-glucosyltransferase regulates grain size and abiotic stress tolerance associated with metabolic flux redirection in rice., 11(1): 2629.

Donnini S, de Nisi P, Gabotti D, Tato L, Zocchi G. 2012. Adaptive strategies of(M.&K.) to calcareous habitat with limited iron availability., 35(6): 1171–1184.

Du H, Wang N L, Cui F, Li X H, Xiao J H, Xiong L Z. 2010. Characterization of the beta-carotene hydroxylase geneconferring drought and oxidative stress resistance by increasing xanthophylls and abscisic acid synthesis in rice., 154(3): 1304–1318.

Du H, Liu L H, You L, Yang M, He Y B, Li X H, Xiong L Z. 2011. Characterization of an inositol 1,3,4-trisphosphate 5/6-kinase gene that is essential for drought and salt stress responses in rice., 77(6): 547–563.

Duan Y B, Li J, Qin R Y, Xu R F, Li H, Yang Y C, Ma H, Li L, Wei P C, Yang J B. 2016. Identification of a regulatory element responsible for salt induction of ricethroughandpromoter analysis., 90: 49–62.

El Mahi H, Pérez-Hormaeche J, de Luca A, Villalta I, Espartero J, Gámez-Arjona F, Fernández J L, Bundó M, Mendoza I, Mieulet D, Lalanne E, Lee S Y, Yun D J, Guiderdoni E, Aguilar M, Leidi E O, Pardo J M, Quintero F J. 2019. A critical role of sodium flux via the plasma membrane Na+/H+exchanger SOS1 in the salt tolerance of rice., 180(2): 1046–1065.

Fang S M, Hou X, Liang X L. 2021. Response mechanisms of plants under saline-alkali stress., 12: 667458.

Fang Y J, Xie K B, Hou X, Hu H H, Xiong L Z. 2010. Systematic analysis of GT factor family of rice reveals a novel subfamily involved in stress responses., 283(2): 157–169.

Fita A, Rodríguez-Burruezo A, Boscaiu M, Prohens J, Vicente O. 2015. Breeding and domesticating crops adapted to drought and salinity: A new paradigm for increasing food production., 6: 978.

Flowers T J, Yeo A R. 1981. Variability in the resistance of sodium chloride salinity within rice (L.) varieties., 88(2): 363–373.

Forni C, Duca D, Glick B R. 2017. Mechanisms of plant response to salt and drought stress and their alteration by rhizobacteria., 410: 335–356.

Fotokian M H, Ahamadi J. 2011. Identification and mapping of quantitative trait loci associated with salinity tolerance in rice () using SSR markers., 9: 21–30.

Fu H H, Luan S. 1998. AtKuP1: A dual-affinity K+transporter from., 10(1): 63–73.

Fukuda A, Nakamura A, Hara N, Toki S, Tanaka Y. 2011. Molecular and functional analyses of rice NHX-type Na+/H+antiporter genes., 233(1): 175–188.

Ganapati R K, Rasul M G, Sarker U, Singha A, Faruquee M. 2020. Gene action of yield and yield contributing traits of submergence tolerant rice (L.) in Bangladesh., 44: 8.

Gao P, Bai X, Yang L, Lv D K, Li Y, Cai H, Ji W, Guo D J, Zhu Y M. 2010. Over-expression of-decreases salt and alkali stress tolerance., 231(5): 991–1001.

Ghosh A, Pareek A, Sopory S K, Singla-Pareek S L. 2014. A glutathione responsive rice glyoxalase II, OsGLYII-2, functions in salinity adaptation by maintaining better photosynthesis efficiency and anti-oxidant pool., 80(1): 93–105.

Greenway H, Munns R. 1980. Mechanisms of salt tolerance in nonhalophytes., 31: 149–190.

Guan Q J, Ma H Y, Wang Z J, Wang Z Y, Bu Q Y, Liu S K. 2016. A rice LSD1-like-type ZFP geneenhances saline-alkaline tolerance in transgenic, yeast and rice., 17: 142.

Guan Q J, Liao X, He M L, Li X F, Wang Z Y, Ma H Y, Yu S, Liu S K. 2017. Tolerance analysis of chloroplast OsCu/Zn-SOD overexpressing rice under NaCl and NaHCO3stress., 12(10): e0186052.

Guo H J, Hu Z Q, Zhang H M, Min W, Hou Z N. 2019. Comparative effects of salt and alkali stress on antioxidant system in cotton (L.) leaves., 17(1): 1352–1360.

Guo M X, Wang R C, Wang J, Hua K, Wang Y M, Liu X Q, Yao S G. 2014. ALT1, a Snf2 family chromatin remodeling ATPase, negatively regulates alkaline tolerance through enhanced defense against oxidative stress in rice., 9(12): e112515.

Guo S H, Niu Y J, Zhai H, Han N, Du Y P. 2018. Effects of alkaline stress on organic acid metabolism in roots of grape hybrid rootstocks., 227: 255–260.

Guo Y, Zhang L, Xiao G, Cao S Y, Gu D M, Tian W Z, Chen S Y. 1997. Expression of betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase gene and salinity tolerance in rice transgenic plants., 40(5): 496–501.

Halfter U, Ishitani M, Zhu J K. 2000. TheSOS2 protein kinase physically interacts with and is activated by the calcium-binding protein SOS3., 97(7): 3735–3740.

Hanin M, Ebel C, Ngom M, Laplaze L, Masmoudi K. 2016. New insights on plant salt tolerance mechanisms and their potential use for breeding., 7: 1787.

Hasanuzzaman M, Bhuyan M H M B, Zulfiqar F, Raza A, Mohsin S M, Mahmud J A, Fujita M, Fotopoulos V. 2020. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant defense in plants under abiotic stress: Revisiting the crucial role of a universal defense regulator., 9(8): 681.

Hasanuzzaman M, Raihan M R H, Masud A A C, Rahman K, Nowroz F, Rahman M, Nahar K, Fujita M. 2021. Regulation of reactive oxygen species and antioxidant defense in plants under salinity., 22(17): 9326.

Hasegawa P M. 2013. Sodium (Na+) homeostasis and salt tolerance of plants., 92: 19–31.

Hasthanasombut S, Supaibulwatana K, Mii M, Nakamura I. 2011. Genetic manipulation ofrice using thegene fromrice to improve salinity tolerance., 104(1): 79–89.

He Y Q, Yang B, He Y, Zhan C F, Cheng Y H, Zhang J H, Zhang H S, Cheng J P, Wang Z F. 2019. A quantitative trait locus,, promotes seed germination and seedling establishment under salinity stress in rice., 97(6): 1089–1104.

Hong C Y, Hsu Y T, Tsai Y C, Kao C H. 2007. Expression ofin roots of rice (L.) seedlings in response to NaCl., 58(12): 3273–3283.

Hong Y B, Zhang H J, Huang L, Li D Y, Song F M. 2016. Overexpression of a stress-responsive NAC transcription factor geneimproves drought and salt tolerance in rice., 7: 4.

Horie T, Horie R, Chan W Y, Leung H Y, Schroeder J I. 2006. Calcium regulation of sodium hypersensitivities ofandmutants., 47(5): 622–633.

Horie T, Sugawara M, Okada T, Taira K, Kaothien-Nakayama P, Katsuhara M, Shinmyo A, Nakayama H. 2011. Rice sodium-insensitive potassium transporter, OsHAK5, confers increased salt tolerance in tobacco BY2 cells., 111(3): 346–356.

Horie T, Karahara I, Katsuhara M. 2012. Salinity tolerance mechanisms in glycophytes: An overview with the central focus on rice plants., 5(1): 11.

Hossain H, Rahman M A, Alam M S, Singh R K. 2015. Mapping of quantitative trait loci associated with reproductive-stage salt tolerance in rice., 201(1): 17–31.

Hossain M A, Lee Y, Cho J I, Ahn C H, Lee S K, Jeon J S, Kang H, Lee C H, An G, Park P B. 2010. The bZIP transcription factor OsABF1 is an ABA responsive element binding factor that enhances abiotic stress signaling in rice., 72: 557–566.

Huang J, Sun S J, Xu D Q, Lan H X, Sun H, Wang Z F, Bao Y M, Wang J F, Tang H J, Zhang H S. 2012. A TFIIIA-type zinc finger protein confers multiple abiotic stress tolerances in transgenic rice (L.)., 80(3): 337–350.

Huang S, Sasaki A, Yamaji N, Okada H, Mitani-Ueno N, Ma J F. 2020. The ZIP transporter family member OsZIP9 contributes to root zinc uptake in rice under zinc-limited conditions., 183(3): 1224–1234.

Ishitani M, Liu J, Halfter U, Kim C S, Shi W, Zhu J K. 2000. SOS3 function in plant salt tolerance requires N-myristoylation and calcium binding., 12(9): 1667–1678.

Ismail A M, Horie T. 2017. Genomics, physiology, and molecular breeding approaches for improving salt tolerance., 68: 405–434.

Jaffar M A, Song A P, Faheem M, Chen S M, Jiang J F, Liu C, Fan Q Q, Chen F D. 2016. Involvement ofin drought tolerance of Chrysanthemum through the ABA-signaling pathway., 17(5): 693.

Jan A, Maruyama K, Todaka D, Kidokoro S, Abo M, Yoshimura E, Shinozaki K, Nakashima K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. 2013. OsTZF1, a CCCH-tandem zinc finger protein, confers delayed senescence and stress tolerance in rice by regulating stress-related genes., 161(3): 1202–1216.

Javid M, Nicolas M, Ford R. 2011. Current knowledge in physiological and genetic mechanisms underpinning tolerances to alkaline and saline subsoil constraints of broad acre cropping in dryland regions.: Shanker A K. Abiotic Stress in Plants: Mechanisms Adaptations. IntechOpen: 193–214.

Joshi R, Sahoo K K, Singh A K, Anwar K, Pundir P, Gautam R K, Krishnamurthy S L, Sopory S K, Pareek A, Singla-Pareek S L. 2020. Enhancing trehalose biosynthesis improves yield potential in marker-free transgenic rice under drought, saline, and sodic conditions., 71(2): 653–668.

Kamiya T, Akahori T, Ashikari M, Maeshima M. 2006. Expression of the vacuolar Ca2+/H+exchanger, OsCAX1a, in rice: Cell and age specificity of expression, and enhancement by Ca2+., 47(1): 96–106.

Karthikeyan A, Pandian S K, Ramesh M. 2011. Transgenicrice cv. ADT43 expressing a Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase () gene fromdemonstrates salt tolerance., 107(3): 383–395.

Kim H Y, Choi E H, Min M K, Hwang H, Moon S J, Yoon I, Byun M O, Kim B G. 2015. Differential gene expression of two outward-rectifying shaker-like potassium channels OsSKOR and OsGORK in rice., 58(4): 230–235.

Koh S, Lee S C, Kim M K, Koh J H, Lee S, An G, Choe S, Kim S R. 2007. T-DNA tagged knockout mutation of rice, an orthologue of, with enhanced tolerance to various abiotic stresses., 65(4): 453–466.

Kotula L, Garcia Caparros P, Zörb C, Colmer T D, Flowers T J. 2020. Improving crop salt tolerance using transgenic approaches: An update and physiological analysis., 43(12): 2932–2956.

Kumar G, Kushwaha H R, Purty R S, Kumari S, Singla-Pareek S L, Pareek A. 2012. Cloning, structural and expression analysis ofin contrasting cultivars of rice under salinity stress., 6(1): 34–41.

Kumar K, Kumar M, Kim S R, Ryu H, Cho Y G. 2013. Insights into genomics of salt stress response in rice., 6(1): 27.

Kumar V, Singh A, Mithra S V A, Krishnamurthy S L, Parida S K, Jain S, Tiwari K K, Kumar P, Rao A R, Sharma S K, Khurana J P, Singh N K, Mohapatra T. 2015. Genome-wide association mapping of salinity tolerance in rice ()., 22(2): 133–145.

Lee S Y, Ahn J H, Cha Y S, Yun D W, Lee M C, Ko J C, Lee K S, Eun M Y. 2007. Mapping QTLs related to salinity tolerance of rice at the young seedling stage., 126(1): 43–46.

Lei L, Zheng H L, Bi Y L, Yang L M, Liu H L, Wang J G, Sun J, Zhao H W, Li X W, Li J M, Lai Y C, Zou D T. 2020. Identification of a major QTL and candidate gene analysis of salt tolerance at the bud burst stage in rice (L.) using QTL-seq and RNA-seq., 13(1): 55.

Li C Y, Fang B, Yang C W, Shi D C, Wang D L. 2009. Effects of various salt-alkaline mixed stresses on the state of mineral elements in nutrient solutions and the growth of alkali resistant halophyte., 32(7): 1137–1147.

Li H W, Zang B S, Deng X W, Wang X P. 2011. Overexpression of the trehalose-6-phosphate synthase geneenhances abiotic stress tolerance in rice., 234(5): 1007–1018.

Li J, Besseau S, Törönen P, Sipari N, Kollist H, Holm L, Palva E T. 2013. Defense-related transcription factors WRKY70 and WRKY54modulate osmotic stress tolerance by regulating stomatal aperture in., 200(2): 457–472.

Li J Y, Sun Y W, Du J L, Zhao Y D, Xia L Q. 2017. Generation of targeted point mutations in rice by a modified CRISPR/Cas9 system., 10(3): 526–529.

Li M, Sun P L, Zhou H J, Chen S, Yu S B. 2011. Identification of quantitative trait loci associated with germination using chromosome segment substitution lines of rice (L.)., 123(3): 411–420.

Li N, Sun J, Wang J G, Liu H L, Zheng H L, Yang L M, Liang Y P, Li X W, Zou D T. 2017. QTL analysis for alkaline tolerance of rice and verification of a major QTL., 136(6): 881–891.

Li N, Zheng H L, Cui J N, Wang J G, Liu H L, Sun J, Liu T T, Zhao H W, Lai Y C, Zou D T. 2019. Genome-wide association study and candidate gene analysis of alkalinity tolerance inrice germplasm at the seedling stage., 12(1): 24.

Li Q, Yang A, Zhang W H. 2016. Efficient acquisition of iron confers greater tolerance to saline-alkaline stress in rice (L.)., 67(22): 6431–6444.

Li W X, Pang S Y, Lu Z G, Jin B. 2020. Function and mechanism of WRKY transcription factors in abiotic stress responses of plants., 9(11): 1515.

Li X W, Zheng H L, Wu W S, Liu H L, Wang J G, Jia Y, Li J M, Yang L M, Lei L, Zou D T, Zhao H W. 2020. QTL mapping and candidate gene analysis for alkali tolerance inrice at the bud stage based on linkage mapping and genome-wide association study., 13(1): 48.

Li X Y, Li S X, Wang J H, Lin J X. 2020. Exogenous abscisic acid alleviates harmful effect of salt and alkali stresses on wheat seedlings., 17(11): 3770.

Li Y G, Ouyang J, Wang Y Y, Hu R, Xia K F, Duan J, Wang Y Q, Tsay Y F, Zhang M Y. 2015. Disruption of the rice nitrate transporter OsNPF2.2 hinders root-to-shoot nitrate transport and vascular development., 5: 9635.

Liang J L, Qu Y P, Yang C G, Ma X D, Cao G L, Zhao Z W, Zhang S Y, Zhang T, Han L Z. 2015. Identification of QTLs associated with salt or alkaline tolerance at the seedling stage in rice under salt or alkaline stress., 201(3): 441–452.

Lima-Melo Y, Carvalho F E L, Martins M O, Passaia G, Sousa R H V, Neto M C, Margis-Pinheiro M, Silveira J A G. 2016. Mitochondrial GPX1 silencing triggers differential photosynthesis impairment in response to salinity in rice plants., 58(8): 737–748.

Lin C M, Koh S, Stacey G, Yu S M, Lin T Y, Tsay Y F. 2000. Cloning and functional characterization of a constitutively expressed nitrate transporter gene,, from rice., 122(2): 379–388.

Lin H X, Zhu M Z, Yano M, Gao J P, Liang Z W, Su W A, Hu X H, Ren Z H, Chao D Y. 2004. QTLs for Na+and K+uptake of the shoots and roots controlling rice salt tolerance., 108(2): 253–260.

Linh L H, Linh T H, Xuan T D, Ham L H, Ismail A M, Khanh T D. 2012. Molecular breeding to improve salt tolerance of rice (L.) in the Red River delta of Vietnam., 2012: 949038.