Generic and disease-specific health-related quality of life in patients with Hirschsprung disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis

Veerle Huizer, Naveen Wijekoon, Danielle Roorda,Jaap Oosterlaan,Marc A Benninga, LW Ernest van Heurn,Shaman Rajindrajith, Joep PM Derikx

Abstract

Key Words: Hirschsprung disease; Health-related quality of life; Meta-analysis; Systematic review; Pediatrics

INTRODUCTION

Hirschsprung disease (HD) is a congenital anomaly with an incidence of approximately 1 in 5000 live births, characterized by a lack of ganglionic cells in the enteric nervous system of a distal segment of the gastrointestinal tract[1 -3 ]. Affected neonates typically present with failure to pass meconium followed by obstructive defecation problems[2 ]. In most patients, the aganglionosis extends no further proximally than the rectum or rectosigmoid, which is defined as short segment disease[4 ]. In some patients aganglionosis is more severe and extends further proximal, with extension to the complete colon or small intestine in 5 %-10 %[5 ]. Definitive surgical management for HD involves resection of the affected bowel segment and restoration of bowel continuity with a straight anastomosis or a pouch[5 ]. Even after surgical resection of the aganglionic segment, it may take years for patients to acquire normal bowel function and continence[2 ]. In addition, patients are at risk of long-term disease-specific problems,including persistent constipation (11 %-16 %)[1 ,6 -11 ], fecal soiling or incontinence (7 %-48 %)[1 ,6 -11 ] or recurrent episodes of enterocolitis (0 %-33 %)[1 ,6 -11 ]. HD can therefore be regarded as a chronic bowel condition, which may severely impact daily functioning.

According to the WHO, quality of life (QoL) can be described as a person’s subjective evaluation of their position in life in the context of their culture and value systems[12 ]. Health-related QoL (HRQoL)describes a person’s subjective evaluation of their physical and mental health[13 ]. HRQoL can be considered as a multidimensional construct and its evaluation generally relies on the patient’s subjective evaluation of well-being and functioning in different aspects and dimensions of well-being and functioning, together resulting in an overall construct[14 ]. Instruments that measure HRQoL can be generic and disease-specific[15 ]. Instruments that measure generic HRQoL can be used to measure HRQoL both in healthy and ill children and can be used for the comparison of HRQoL accros different conditions and settings, whereas disease-specific HRQoL instruments only measure HRQoL in patients with a certain condition, and are typically better in detecting changes in HRQoL over time[15 ]. For patients with HD the disease-specific questionnaire HAQL (Hirschsprung disease / Anorectal malformation Quality of Life) has been developed[4 ].

There is growing interest in HRQoL of patients with HD, as shown by the increasing number of studies reporting on generic and disease-specific HRQoL in these patients. The current body of evidence is inconsistent about whether HRQoL and functional outcomes are lower in patients with HD compared to healthy controls[6 ,7 ,11 ,15 ,16 ]. The available literature suggests evidence for several factors to be related to HRQoL and functional outcomes, including patient age[1 ,3 ,17 ], the use of parental proxyvsself-report[18 ], length of aganglionosis[19 ], type of surgical procedure and anastomosis technique used in surgery[20 ], postoperative complications[20 -25 ], presence of a stoma[26 -28 ] and syndromal anomalies[29 ]. Thus far the available evidence on generic HRQoL and disease-specific HRQoL among HD patients has not been systematically reviewed and aggregated precluding clear conclusions to be drawn.

The primary aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to summarize all available evidence on differences in generic health-related quality of life between patients with HD and normative data.Secondary aim was to summarize available evidence on disease-specific health-related quality of life of patients with HD. Third aim was to study patient and clinical factors that could explain differences in generic HRQoL between patients and normative data, including sex, age, the use of parental proxyvsself-report, length of aganglionosis, operation technique, postoperative complications, presence of stoma and syndromal anomalies using meta-regression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This meta-analysis was conducted according to the PRISMA guidelines[30 ].

Eligibility criteria

The following eligibility criteria were used: (1 ) The sample consisted of patients diagnosed with HD and a medical history of surgical resection of the affected bowel segment; (2 ) The majority of the patients included in the study had the age between 0 and 18 years old at assessment; (3 ) Generic HRQoL was measured as outcome; (4 ) Studies had an observational or case-control design and used HRQoL measures for which normative data is available, or compared patients with HD with normative data or a healthy control group; and (5 ) The study reported original data, with a minimum sample size arbitrarily set atn= 10 . Studies were excluded if the full text was only available in a language other than English.

Search and selection

Pubmed, Web of Sciences, PsycInfo and Embase were searched using entry terms related to:‘Hirschsprung disease’, ‘Pediatrics’ and ‘Quality of life’. The full search strategy can be found in the Supplementary Material. Reference lists of included articles were checked for additional studies matching our eligibility criteria. Screening of title, abstract and full-text of the studies was performed by two independent researchers (N.W. and V.H.) using the online software Covidence[31 ]. Initial disagreements on study selection were discussed and in case of persistent conflicting judgement, a third party (D.R.) was consulted to reach consensus.

Data extraction

As primary outcome measurement, the mean scores and corresponding standard deviation of generic HRQoL were extracted by one researcher (V.H.). Additionally, the following characteristics were extracted from each study: domain scores (physical, psychosocial and social HRQoL), publication year,study design, sample size, type of questionnaire used to assess HRQoL, mean age of patients,percentage of male patients , percentage of measurements with parental proxy and self-report,percentage of patients with short aganglionic bowel segment, type of surgery (percentage of patients operated using the Duhamel technique and percentage of patients operated using Transanal Endorectal Pull-through [TEPT] technique), percentage of patients with postoperative complications, percentage of patients with a stoma present, and percentage of patients who had a syndromal comorbidity. If required data was not reported, authors were requested by email to provide additional data. In case of nonresponse of the author after one reminder and when available data was not sufficient for adequate analysis, the study was excluded from the analyses. In case a study reported median generic HRQoL scores, these were recalculated to mean scores[32 ,33 ], or else the median was considered to be the best approximation of the mean. For those studies that did not include a control group, questionnaire specific local age- and sex-matched normative values were used and compared with the reported outcomes of patients with HD[34 -39 ].

Quality assessment

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to assess quality of the studies in this meta-analysis[40 ].According to the manual, we adapted the scoring system to our study design. A detailed description of the adjustment can be found in the Supplementary Material. The included studies were rated on a 9 -point rating scale by two of the authors (N.W. and V.H.), based on aspects of participant selection (4 points), group comparability (2 points) and outcome assessment (3 points). Quality of studies was considered good, fair and poor using AHRQ (Agency for Health Research and Quality) criteria[41 ].Rating discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using CMA (Comprehensive Meta-Analysis)[42 ]. The standardized mean difference (expressed as Cohen’s d) of generic HRQoL and domain scores between patients with HD and healthy control or normative populations were calculated for each study. Effect sizesdof 0 .2 ,0 .5 and 0 .8 were taken as thresholds to define small, medium and large effects, respectively[43 ]. For all outcomes, heterogeneity of effect sizes was quantified usingI2statistic. Heterogeneity was regarded small (I2≤ 0 .25 ), moderate (0 .25 < I2 < 0 .50 ) or large (I² ≥ 0 .50 ), according to Higgins[44 ]. In case of moderate or large heterogeneity, random effects models were used.

Individual study findings were presented in forest plots and aggregated into summary estimates of standardized mean differences for: (1 ) Generic HRQoL; (2 ) Physical HRQoL; (3 ) Psychosocial HRQoL;and (4 ) Social HRQoL. In case a study reported on more than one outcome, within study findings were pooled into an weighted estimate on these predefined domains, using a built-in function in CMA. A detailed description of which items in different HRQoL-measurements were pooled into domain scores can be found in the Supplementary Material. In case a study reported no generic HRQoL score, the mean of at least two reported domain scores was considered as a reflection of the generic HRQoL.

Publication bias analysis included visual inspection of funnel plots and calculation of Egger’s intercept. Robustness of the calculated aggregated effect sizes against the influence of publication bias was assessed with fail safe N. An effect was considered robust when fail safe N > 5 k+10 [45 ].

To explore sources of heterogeneity, subgroup analyses were performed to assess differences in each of the HRQoL outcomes between: (1 ) Studies reporting on different age groups ([< 12 years], [12 -16 years] and [16 + years]); (2 ) Studies using different questionnaires to assess HRQoL (for example assessment by the CHQvsPedsQL); (3 ) Studies that used a control group and studies that used normative reference data; and (4 ) Studies that reported generic HRQoL scores and studies in which a generic score was constructed from domain scores. Sensitivity analysis was used to explore the influence of study quality on summary estimates of all HRQoL outcomes. The moderating effect of sex and parental proxyvsself-report on generic HRQoL scores was explored using univariate metaregression which was only conducted in case of at least 10 observations.

Narrative analysis of disease-specific HRQoL

Since the HAQL is a disease-specific questionnaire, a quantitative comparison with healthy controls could not be made. Designating one cohort as reference group is random and was therefore not considered to be meaningful in this context. Thus pooled summary estimates for the HAQL scores were made and findings within individual studies, in term of domains on which relatively lower diseasespecific HRQoL scores were reported, were narratively described.

RESULTS

The flowchart of the study search and selection process is provided in Figure 1 . Our search yielded 334 unique records, of which 17 studies (n = 1141 patients) were included in the current systematic review and of which 15 studies contributed data to the meta-analysis.

Study characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the 17 included studies. Of the 17 studies, 15 studies measured generic HRQoL and four studies measured disease-specific HRQoL. The PedsQL was most frequently used to assess generic HRQoL (in 10 of 15 studies). All four studies used the HAQL to assess diseasespecific HRQoL. Four out of 17 studies used a controlled study design. Patients’ ages ranged from 0 to 21 years.

Generic Health-related Quality of Life

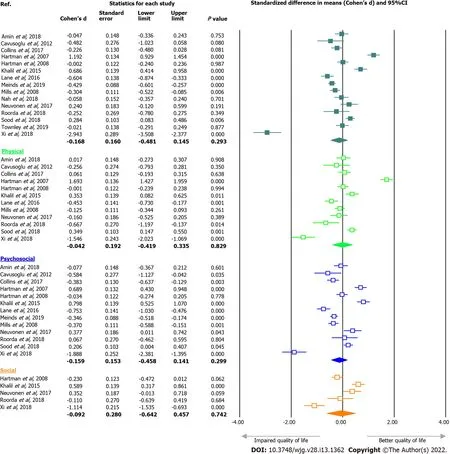

Generic HRQoL: Fifteen (15 ) studies (n = 1024 patients) were included in the meta-analysis comparing patients with HD to normative data or controls on generic HRQoL. A significantly lower generic HRQoL was found for patients with HD in 4 out of 15 studies, whereas 3 out of 15 studies found a significantly higher generic HRQoL in patients. Meta-analytic aggregation showed a non-significantly impaired generic HRQoL (d=-0 .168 [95 %CI: -0 .481 ; 0 .145 ], P = 0 .293 , I² = 94 .9 ) in patients with HDcompared to healthy controls (Figure 2 ). Visual interpretation of the funnel plot and Egger’s test (t=0 .841 ; P = 0 .416 ) suggested that there was no indication of publication bias, and the aggregated effect was also not robust with a fail safe N of 9 studies.

Table 1 Characteristics of included studies

Figure 1 PRISMA flowchart of study selection.

Physical HRQoL:Twelve (12 ) studies (n = 774 patients) were included in the meta-analysis comparing patients with HD to normative data or controls on physical HRQoL. A significantly lower physical HRQoL was found for patients with HD in 3 out of 12 studies, whereas 3 out of 12 studies found a significantly higher physical HRQoL in patients. Meta-analytic aggregation showed a non-significantly lower physical HRQoL (d= -0 .042 [95 %CI: -0 .419 ; 0 .335 ], P = 0 .829 , I² = 95 .1 ) in patients with HD compared to healthy controls (Figure 2 ). Visual interpretation of the funnel plot and Egger’s test (t=1 .391 ; P = 0 .194 ) suggested that there was no indication of publication bias, and the aggregated effect was also not robust with a fail safe N of 0 studies.

Psychosocial HRQoL:Thirteen (13 ) studies (n = 924 patients) were included in the meta-analysis of comparing patients with HD to normative data or controls on psychosocial HRQoL. A significantly lower psychosocial HRQoL was found for patients with HD in 6 out of 13 studies, whereas 4 out of 13 studies found a significantly higher psychosocial HRQoL in patients. Meta-analytic aggregation showed a non-significantly lower psychosocial HRQoL (d= -0 .159 [95 %CI: -0 .458 ; 0 .141 ], P = 0 .299 , I² = 93 .6 ) in patients with HD compared to healthy controls (Figure 2 ). Visual interpretation of the funnel plot and Egger’s test (t= 0 .476 ; P = 0 .643 ) suggested that there was no indication of publication bias, and the aggregated effect was also not robust with a fail safe N of 18 studies.

Social HRQoL:Five (5 ) studies (n = 308 patients) were included in the meta-analysis comparing patients with HD to normative data or controls on social HRQoL. A significantly lower social HRQoL was found for patients with HD in 1 out of 5 studies, whereas 1 out of 5 studies found a significantly higher social HRQoL in patients. Meta-analytic aggregation showed a non-significantly lower social HRQoL (d= -0 .092 [95 %CI: -0 .642 ; 0 .457 ], P = 0 .742 , I² = 92 .3 ), in patients with HD compared to healthy controls(Figure 2 ). Visual interpretation of the funnel plot and Egger’s test (t = 0 .554 ; P = 0 .618 ) suggested there was no indication of publication bias, and the aggregated effect was also not robust with a fail safe N of 0 studies.

Patient and clinical factors explaining differences in generic HRQoL

Table 2 summarizes the results from the subgroup analyses. Meta-analytic effects for generic HRQoL did not significantly differ between age groups. There was an influence of the type of questionnaire used, as meta-analytic aggregation of studies using the CHQ showed a significant medium-sized impairment in generic HRQoL in patients with HD compared to normative data or controls, whereas meta-analytic aggregation of studies using the TACQoL or PedsQL showed no significant differences.Meta-analytic aggregation also showed no significant differences between studies comparing patients tonormative reference data and studies comparing patients with constructed control groups. The complexity of the construct of generic HRQoL was expressed by the difference that was seen when comparing the effects sizes of studies reporting generic HRQoL scores and studies for which a generic HRQoL score was derived from the average of domain scores. Meta-analytic aggregation showed a significant medium-sized impairment in generic HRQoL when only studies were included that reported generic HRQoL scores, whereas meta-analytic aggregation showed no significant effect when only studies were included in which a generic HRQoL score was constructed from the average of the reported domain scores. There was no relationship between the percentage of male patients in studies and the individual study’s effect sizes for generic HRQoL (b= 0 .308 , P = 0 .631 , R² = 0 .00 ). Also the percentage of measurements with self-report in studies was not significantly associated with effect sizes for generic HRQoL (b= 0 .331 , P = 0 .467 , R² = 0 .00 ). Based on the amount of observations, statistical power was too small to test the influence of age, length of aganglionosis, operation technique,postoperative complications, presence of stoma and syndromal anomalies on generic HRQoL of patients with HD.

Table 2 Differences in health-related quality of life scores in subgroup analyses

Disease-specific health-related quality of life

Disease-specific HRQoL was reported in 4 studies (n = 252 patients). Hartman et al[49 ] only reported an overall QoL score, with 5 domain scores constructed into a single HAQL score (18 .3 ± 1 .7 ), which represented a good disease-specific HRQoL, but none of the other studies with the HAQL used this total disease-specific HRQoL score, making it impossible to compare these findings to those obtained in other studies. The domain scores of the remaining 3 studies were aggregated to construct summary estimates for the HAQL scores, of which an overview is presented in Table 3 . Physical symptoms impacted disease-specific physical HRQoL negatively in all 3 studies, which is similar to the findings reported by Hannemanet al[4 ], where physical symptoms had the lowest mean rank score. Across all studies,diarrhea was the second factor to negatively impacted disease-specific HRQoL, and – to a lesser extent -fecal incontinence. The domains laxative diet, constipating diet, constipation, urinary continence, social functioning, emotional functioning and body image had no significant negative impact on diseasespecific HRQoL. In summary, all studies showed an impairment on disease-specific physical HRQoL.Psychosocial and social HRQoL were not negatively influenced by disease-specific complaints in all four studies.

Quality of the evidence

The majority of the studies in the current systematic review were of good quality (10 out of 17 studies,59 %), whereas one study was of fair and 6 studies were of poor quality according to the NOS (Table 4 ).Meta-analytic estimates of generic HRQoL did not differ significantly between studies of good, fair and poor quality (Q= 2 .220 ; P = 0 .330 ), neither did meta-analytic estimates of physical HRQoL (Q = 4 .391 ;P= 0 .111 ) and psychosocial HRQoL (Q = 2 .705 ; P = 0 .259 ). However, meta-analytic estimates of social HRQoL did differ significantly between studies of good, fair and poor quality (Q= 9 .285 ; P = 0 .010 ).More specifically, social HRQoL was rated higher in the one study of low quality (d= 0 .589 [95 %CI:0 .317 ; 0 .861 ], P < 0 .001 , n = 1 ), compared to those of fair and good quality.

Table 4 Study quality assessment according to the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale criteria

When including only studies of good quality, meta-analytic aggregation showed a medium-sized significantly impaired generic HRQoL in patients compared to normative data or controls (d= -0 .342 [95 %CI: -0 .665 ; -0 .019 ], P = 0 .038 ). When including only studies of good quality for psychosocial HRQoL,meta-analytic aggregation showed a medium-sized significantly impaired psychosocial HRQoL (d=-0 .339 [95 %CI: -0 .656 ; -0 .022 ], P = 0 .036 ), whereas meta-analytic aggregation of only studies with good quality showed no significant differences between patients and normative data or controls for physical HRQoL (d= -0 .199 [95 %CI: -0 .527 ; 0 .129 ], P = 0 .235 ) and social HRQoL (d = -0 .322 [95 %CI: -1 .033 ; 0 .390 ],P= 0 .376 ).

Figure 2 Forest plots of total health-related quality of life (HRQoL), physical HRQoL, psychosocial HRQoL and social HRQoL of patients with Hirschsprung disease compared to normative data.

DISCUSSION

The findings of this systematic review and meta-analysis suggest that generic HRQoL is not impaired in patients with HD compared to healthy controls and that physical HRQoL is most impaired as a result of disease-specific complaints. The high heterogeneity in HRQoL findings among the included studies implies that there are underlying factors moderating the HRQoL of patients with HD. Our findings indicated that generic HRQoL is not influenced by sex and type of respondent (parental proxy or selfreport) and that generic HRQoL did not differ significantly between different age groups. The quantity of the available evidence did not allow to test for the moderating effect of length of aganglionosis,operation technique, postoperative complications, presence of a stoma and the presence of a syndromal anomalies on generic HRQoL.

Findings in several studies have shown no differences in HRQoL between male and female patients,which also corresponds to our findings[26 ,46 -48 ]. Furthermore, there is evidence suggesting that HRQoL varies with increasing age and is influenced by factors like coping strategies[23 ,48 ,49 ] and psychological changes accompanying life events, including puberty[11 ,16 ,25 ,26 ,49 -54 ]. Adolescents may have less ability to adapt their lifestyle because of the influence of peer pressure and the wish to adapt to their peers and not be different from their peers. Adult patients and parents of patients with HD are more capable to adapt their lifestyle, which may result in better HRQoL in children and adults patients,compared to adolescent patients. Findings in previous studies have shown that parents tend to overestimate problems and impairments in patients with chronic diseases[41 ,55 -58 ]. This in turn may be influenced by their cultural, social and educational background[39 ,46 ,53 ,59 ]. Also anxiety in parents of patients with HD may play an important role as well[54 ,60 ].

The severity of HD may also impact HRQoL. In this meta-analysis we could not test for the relation between length of disease and generic HRQoL. Findings from earlier studies are inconsistent[26 ,48 ,61 ,62 ], but suggest that HRQoL may not so much be dependent on length of disease itself, but with factors associated with differences in length of aganglionosis, including occurrence of obstructive defecation problems, postoperative complications and the operation technique that was used[49 ,53 ,61 ,63 ]. Also,current evidence is inconclusive on which type of the operation technique is associated with better HRQoL outcome[63 -66 ]. Frequently reported disease-specific sequelae including obstipation[1 ,11 ,16 ,23 ,25 ,26 ,48 ,49 ,53 ,61 ,67 ,68 ], fecal incontinence[1 ,11 ,16 ,23 ,25 ,26 ,48 ,49 ,53 ,61 ,67 ,68 ] and the presence of a stoma[1 ,11 ,16 ,23 ,25 ,26 ,48 ,49 ,53 ,61 ,67 ] have shown to be associated with impaired HRQoL.

Previous studies have suggested that patients with HD who have an associated syndrome, may have lower HRQoL than patients with non-syndromal HD. In particular Down syndrome is known to be associated with lower QoL[29 ,69 ]. Patients with an associated syndrome unfortunately were underrepresented in the studies included in this meta-analysis, as these patients were often excluded from questionnaire surveys because of mental retardation that is associated with syndromes. Therefore, the influence of having an associated syndrome on HRQoL outcome could not be assessed in this study.

Our findings indicate that overall HRQoL estimates cannot simply be calculated by taking the average of domain scores, suggesting different weight of different aspects of health on the overall evaluation of HRQoL. This may be explained by differences in the items based on which the domain scores are constructed, which varies between questionnaires. But it may also reflect that HRQoL is a challenging multidimensional construct to measure. Some dimensions of health may have more influence on overall HRQoL than others, which may be based on the extent to which functioning in that domain is limited, but may also be under the influence of personal beliefs, goals and coping strategies.

The relationship between functional outcome and HRQoL outcome also remains subject to debate.Based on the available evidence in the current study, the relationship between functional outcome and HRQoL could not be tested. Our findings on disease-specific HRQoL suggest that some disease-specific symptoms, in particular diarrhea and fecal incontinence, may impair physical functioning of patients with HD rather than psychosocial and social functioning. Differences in outcome may be explained by differences in selection of cohorts between the few studies describing disease-specific HRQoL, as some cohorts included patients with Anorectal Malformation (ARM) and another cohort consisted only of patients with a severe form of HD: Total Colonic Aganglionosis (TCA)[61 ,70 ].

Heterogeneity in findings on generic HRQoL outcome may be explained by methodological aspects.Although we found no differences in HRQoL scores between studies that compared HRQoL findings of patients with HD to a normative cohort, and studies that compared HRQoL findings with a selected cohort of controls, sensitivity analysis showed that when aggregating only studies of good quality,overall and psychosocial HRQoL of patients with HD is significantly lower compared to healthy controls. This suggests our main findings on overall and psychosocial HRQoL may have overestimated overall and psychosocial HRQoL outcomes in patients with HD, resulting in a smaller difference compared to healthy controls.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first meta-analysis that summarizes the available evidence on HRQoL outcome of patients with HD. Our findings must be interpreted in the light of a few limitations. First, we could not test whether HRQoL is moderated by length of aganglionosis, operation technique, postoperative complications, presence of stoma and the presence of an associated syndrome, because of the small number of studies with complete data of study- and patient characteristics. Although for a few factors the moderation on HRQoL findings was tested in this study, this was done by meta-regression or groupcomparison of meta-analytic findings. This type of analysis does not allow for the calculation of direct relations but calculates relations between studies’ averages or proportions and studies effect sizes.Second, there was large heterogeneity in HRQoL findings among the small amount of included studies,resulting in non-robust effects in this study. Third, the evidence of this meta-analysis is based on small,cross-sectional studies, which makes it impossible to assess longitudinal trends in HRQoL, and to assess the influence of transitions in life including puberty and adolescence on HRQoL. Our findings showed no linear relationship between age and HRQoL, but this relation may not be linear. The subgroup analysis did not indicate significant differences between age groups, but is limited by the randomness of the cut-off values used to group the patients into age groups. A last limitation of this meta-analysis is that different instruments to measure HRQoL make different estimations, we aimed to correct for this by including the difference of patients with Hirschsprung disease with normative data in the metaanalysis, which is less vulnerable to a bias introduced by variance between instruments than directly including scores.

Risk of bias

There was a risk of selection bias, as some included studies consisted of a cohort with patients with anorectal malformations and patients with Hirschsprung disease, and also because patients with Down syndrome were underrepresented. Although we tried to limit the influence of information bias by including only studies that used questionnaires that had shown to have adequate construct validity to measure HRQoL, there was heterogeneity in HRQoL outcomes assessed by the different instruments.Differences in the design of the questionnaires, the amount of detail assess with the different items and constitution of domain scores may account for this. There was no evidence of an influence of publication bias on our findings based on Egger’s intercept and visual inspection of funnelplots (presented in the Supplementary Material), although findings were not very robust with low fail safe N’s.

CONCLUSION

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, no evidence was found for impaired HRQoL outcome in patients with HD compared to healthy controls, neither for the moderating effect of sex, parental proxy or self-report on HRQoL outcome. Physical functioning was most impaired by disease-specific complaints. To further study the longitudinal trends in HRQoL and determinants of HRQoL in patients with HD, we need longitudinal studies that assess the relationship between patient characteristics,functional outcomes and HRQoL.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank F.S. van Etten-Jamaludin (AMC clinical librarian) for assistance during the search construction for this meta-analysis and review.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Huizer V, Roorda D, Derikx JPM and Rajindrajith S designed the study and designed data collection; Huizer V and Wijekoon N performed study selection, performed study quality assessment, collected data,carried out the initial analyses, drafted the initial manuscript and revised the manuscript; Roorda D supervised data collection, statistical analyses and critically reviewed the manuscript; Derikx JPM, Rajindrajith S, Benninga MA, van Heurn LWE and Oosterlaan J reviewed the manuscript; all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Conflict-of-interest statement:All authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

PRISMA 2009 Checklist statement: The authors have read the PRISMA 2009 Checklist, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4 .0 ) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4 .0 /

Country/Territory of origin:Netherlands

ORCID number:Veerle Huizer 0000 -0001 -9466 -9861 ; Naveen Wijekoon 0000 -0002 -6721 -5546 ; Daniëlle Roorda 0000 -0001 -9740 -4957 ; Jaap Oosterlaan 0000 -0002 -0218 -5630 ; Marc A Benninga 0000 -0001 -9406 -9188 ; LW Ernest van Heurn 0000 -0002 -8001 -1222 ; Shaman Rajindrajith 0000 -0003 -1379 -5052 ; Joep PM Derikx 0000 -0003 -0694 -7679 .

S-Editor:Wang LL

L-Editor:A

P-Editor:Wang LL

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年13期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年13期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Therapeutic drug monitoring in inflammatory bowel disease: At the right time in the right place

- Endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer: Towards a global understanding

- Locoregional therapies and their effects on the tumoral microenvironment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- Increased prognostic value of clinical–reproductive model in Chinese female patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- Comparison of the performance of MS enteroscope series and Japanese double- and single-balloon enteroscopes

- Management of incidentally discovered appendiceal neuroendocrine tumors after an appendicectomy