Management of incidentally discovered appendiceal neuroendocrine tumors after an appendicectomy

José Luis Muioz de Nova, Jorge Hernando, Miguel Sampedro Nuiez,Greissy Tibisay Vazquez Benitez, EvaMaria Triviio Tbaniez,Maria Isabel del Olmo Garcia, Jorge Barriuso, Jaume Capdevila,Elena Martin-Pérez

Abstract Appendiceal neuroendocrine tumors (aNETs) are an uncommon neoplasm that is relatively indolent in most cases. They are typically diagnosed in younger patients than other neuroendocrine tumors and are often an incidental finding after an appendectomy. Although there are numerous clinical practice guidelines on management of aNETs, there is continues to be a dearth of evidence on optimal treatment. Management of these tumors is stratified according to risk of locoregional and distant metastasis. However, there is a lack of consensus regarding tumors that measure 1 -2 cm. In these cases, some histopathological features such as size, tumor grade, presence of lymphovascular invasion, or mesoappendix infiltration must also be considered. Computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging scans are recommended for evaluating the presence of additional disease, except in the case of tumors smaller than 1 cm without additional risk factors. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy or positron emission tomography with computed tomography should be considered in cases with suspected residual or distant disease. The main point of controversy is the indication for performing a completion right hemicolectomy after an initial appendectomy, based on the risk of lymph node metastases. The main factor considered is tumor size and 2 cm is the most common threshold for indicating a colectomy. Other factors such as mesoappendix infiltration, lymphovascular invasion,or tumor grade may also be considered. On the other hand, potential complications, and decreased quality of life after a hemicolectomy as well as the lack of evidence on benefits in terms of survival must be taken into consideration. In this review, we present data regarding the current indications,outcomes, and benefits of a colectomy.

Key Words: Neuroendocrine tumors; Carcinoid tumor; Appendiceal neoplasms; Colectomy; Neoplasm grading; Treatment outcome

INTRODUCTION

More than 80 % of appendiceal neuroendocrine tumors (aNETs) are diagnosed incidentally in appendectomy specimens and are found in approximately 0 .5 % to 1 % of all appendectomies[1 ]. These neoplasms have several characteristic features that differ from other gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-NETs). They usually progress indolently and are diagnosed in younger patients other NETs; the majority are detected in the third or fourth decade of life while other NETs are usually diagnosed close to the sixth decade of life[2 -5 ]. Nevertheless, these tumors do occasionally have an aggressive course with liver and mesenteric lymph node metastasis (LNM)[6 ]. In a recent review of patients included in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database, the five-year survival rates for aNETs are 97 .4 %, 88 .6 %, and 27 .4 % for localized, regional, and distant disease, respectively.Non-metastatic aNETs had the highest overall survival rate of all GEP-NETs[7 ].

Surgery is curative in most cases[3 ]. However, controversy arises when deciding whether an appendectomy alone is sufficient or whether the patient will achieve better outcomes with a completion right hemicolectomy (CRH) after an initial appendectomy. The main purpose of a CRH is to complete the regional lymph node dissection. These nodes are involved in 6 % to 9 % of cases[8 ]. Both the North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society[9 ] and European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS)[10 ] guidelines suggest a tailored approach to these patients based on features such as tumor size,margin status, mesoappendix infiltration, vascular and lymphatic invasion, and tumor grade. In tumors smaller than 1 cm, an appendectomy is indicated whereas in those larger than 2 cm, a CRH is recommended. In tumors between 1 and 2 cm, CRH should be considered when there are affected margins in tumors located at the base, when there is invasion of the mesoappendix that measures greater than 3 mm, or when there are other risk factors. However, several studies have challenged these recommendations, mainly in tumors smaller than 2 cm, arguing that CRH offers no benefits in terms of survival in tumors smaller than 2 cm[8 ,11 ]. Furthermore, in addition to the potential postoperative complications, a colectomy could lead to a poorer quality of life for these patients.

This narrative review critically evaluates the management of these patients based on evidence in the current literature with a special focus on the indications for and outcomes of a CRH.

WHAT ARE THE FEATURES ANALYZED IN THE HISTOPATHOLOGICAL DIAGNOSIS?

A careful histopathological evaluation of the surgical specimen will provide crucial information for determining management. aNETs are epithelial neoplasms that likely arise from neuroendocrine cells,including enterochromaffin cell neuroendocrine tumors, L-cell NETs, and tubular NETs. Their pathogenesis is largely unknown. Their hypothetical origins include neuroendocrine cells within the mucosal crypts or subepithelial neuroendocrine cells, especially in enterochromaffin cell NETs[12 ,13 ].

Appendiceal neoplasms include well-differentiated aNETs (classified as low grade-G1 , intermediate grade-G2 , or high grade-G3 according to proliferative rate), poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma, and mixed neuroendocrine-non neuroendocrine neoplasms (MINEN). Between 70 % to 75 %of neuroendocrine neoplasms in the appendix are well-differentiated NETs. Goblet cell adenocarcinoma is no longer considered a subtype of aNET[13 ,14 ]. Goblet cell adenocarcinoma and MINEN will not be discussed further in this review.

Macroscopically, most of these cases are found incidentally on the tip of the appendix after an appendectomy for acute appendicitis. They are usually yellowish nodules and most are smaller than 2 cm in diameter (only 8 % to 19 % are larger than 2 cm)[15 ,16 ].

Microscopically, well-differentiated aNETs include:

Enterochromaffin cell appendiceal neuroendocrine tumors (EC-NETs): This is the most common subtype. EC-NETs usually appear as uniform polygonal cells arranged in nests or a glandular pattern with a fibrotic stromal response. Necrosis and mitosis are uncommon. Immunohistochemistry techniques demonstrate positivity to chromogranin A (CgA), synaptophysin, and serotonin production in EC cells[15 ,17 ] (Figure 1 ).

L-cell NETs: These tumors have trabecular or glandular growth patterns. L-cell NETs produce glucagon-like peptide 1 and proglucagon-derived peptides. L-cell NETs express chromogranin B rather than CgA[14 ].

Tubular NETs: These tumors represent < 10 % of all aNETs[8 ] and must be distinguished from adenocarcinoma NOS and goblet cell adenocarcinoma[14 ].

Whether a tumor is an EC or L-cell NET is usually not specified on pathology reports as this distinction has no prognostic or therapeutic implications[14 ,18 ].

Poorly differentiated aNETs are rare and are microscopically similar to other intestinal neuroendocrine carcinomas[15 ,17 ,19 ].

The staging of aNETs is mainly based on tumor size and serosal or mesoappendix invasion. The pathology report should also include pTNM staging (according to either American Joint Committee on Cancer classification[20 ], ENETS classification[10 ], or both), margin status, and vascular and lymphatic vessel involvement (Table 1 ). Mesoappendix invasion is usually associated with a higher rate of vascular and lymphatic vessel involvement[10 ,15 ,17 ].

WHAT ADDITIONAL TESTS ARE RECOMMENDED IN CASES OF ANET?

After an incidental diagnosis of aNET, the main purpose of additional tests is to assess the presence of residual locoregional disease or distant metastasis in order to determine postoperative staging.

Biochemical tests

There are no clear benefits to measuring any specific biomarker in aNETs[10 ]. Although CgA is a widely used biomarker for evaluating and following-up on GEP-NETs, its role in aNETs is unclear. CgA levels are usually within normal range in NETs with a low proliferative potential, which are the majority of aNETs[21 ]. It has been suggested that its measurement may only be useful in advanced cases[10 ].Carcinoid syndrome is uncommon at the time of diagnosis[2 ], but when it is suspected, determination of urinary 5 -hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5 -HIAA) could be useful[10 ].

Endoscopy

The usefulness of performing an endoscopy after an incidental diagnosis of aNETs seems to be negligible unless the tumor infiltrates the cecum[10 ].

Conventional imaging tests

After a complete resection of an incidentally diagnosed well-differentiated aNET measuring < 1 cm, no further diagnostic testing is required. However, controversy remains regarding tumors that measure between 1 and 2 cm, since these tumors rarely have LNM. To evaluate the presence of lymphatic involvement or distant metastasis, an abdominal computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonanceimaging (MRI) scan is recommended. These tests should also be considered for tumors > 2 cm or for those with mesoappendix infiltration or vascular and lymphatic vessel invasion. In these cases,somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (SRS) or a positron emission tomography with computed tomography (PET/CT) scan should be considered[10 ].

Table 1 TNM staging for appendiceal neuroendocrine tumor according to European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society and American Joint Committee on Cancer classification

Figure 1 Histological images. A: Well-differentiated aNET that infiltrate the entire wall of the appendix and focally infiltrate the adjacent fat, affecting the surgical margin; B: Immunohistochemical techniques reveal positivity for synaptophysin and CgA.

Nuclear medicine imaging

There are a multitude of articles on the applications of SRS in GEP-NETs, however, only sporadic cases of aNET have been described in this body of literature[22 ,23 ]. SRS using either indium-111 or technetium-99 m (including single photon emission CT) or a PET scan using gallium-68 -labeled somatostatin analogs (SSAs) in combination with a CT scan can be considered in cases in which curative resection is not completely assured or when distant metastasis is suspected[24 ]. In these cases,published studies suggest that SRS is useful for detecting residual disease[23 ,25 ] and that SRS results could modify management in 20 % to 25 % of patients[23 ,26 ], mainly for those with high proliferative activity.

Positron emitting radiopharmaceuticals such as gallium-68 -labeled peptides or 18 F-fluorodopamine are now preferred for the diagnosis of well-differentiated GEP-NETs, particularly those smaller than 1 cm[10 ]. These PET radiopharmaceuticals provide greater resolution, faster results, shorter imaging time,and 3 D visualization. However, due to their cost and availability, their use is not yet widespread. 18 F-2 -fluoro-2 -deoxy-glucose PET/CT is recommended for detecting poorly differentiated or heterogeneous NETs[27 ]. Furthermore, even though these radiopharmaceuticals have been widely studied in other GEP-NETs, to date no works have evaluated their usefulness specifically in aNETs.

INDICATIONS IN THE LITERATURE FOR A COMPLETION RIGHT COLECTOMY

Most cases of aNET are patients with a tumor < 1 cm in the distal third of the appendix. The presence of risk factors associated with more extensive disease, such as serosal or mesoappendix invasion, are usually associated with tumors greater than 2 cm[2 ].

After a CRH, residual disease or lymph node involvement is present in 0 % to 40 % of cases[2 ,8 ,28 ]. A recent review by Webbet al[11 ] of patients in the National Cancer Database treated with surgery found that, unlike other types of appendiceal neoplasms, in aNET, the presence of regional LNM does not reduce overall survival. Since most studies supporting the indication of a CRH are based on completing a lymph node dissection, the claim that this procedure improves patient survival is highly questionable.

The main indications for CRH are based on the following evidence:

Tumor size: Some recent studies suggest that size is the main factor related to the occurrence of LNM[1 ,8 ,15 ,29 ,30 ]. As stated above, controversy arises in aNETs that are greater than 2 cm and those from 1 to 2 cm, which represent from 3 % to 7 % and from 20 % to 25 % of cases, respectively[8 ,28 ]. The 10 -year survival rate according to size is 100 %, 92 %, and 91 % for < 1 cm, 1 to 2 cm, and > 2 cm, respectively[31 ].Although the indication is most likely a continuum, it has been suggested that 2 cm may be the optimal cut-off point for presence of LNM[1 ]. Current guidelines recommend this size for considering a CRH after an appendectomy and to consider CRH for tumors from 1 to 2 cm when other risk factors are present. In a recent meta-analysis, the rate of LNM was 12 .1 %, 38 .5 %, and 61 % for tumors measuring < 1 cm, 1 to 2 cm, and > 2 cm, respectively[32 ]. A reduction in the cut-off point for a colectomy from 15 mm to 13 mm regardless of other features has been proposed due to the possible presence of LNM, but no studies have found any benefit in terms of recurrence or survival[5 ,28 ].

Mesoappendix invasion: Its incidence ranges from 23 % to 39 %[5 ,8 ,28 ]. There is controversy in the literature regarding its prognostic relevance. Some studies have found no effects on the recurrence rate[33 ] or presence of LNM[1 ,8 ], while others suggest that the disease behaves more aggressively in these patients[17 ,31 ]. A recent publication found that presence of mesoappendix invasion entails a higher risk of LNM and suggests an optimal cut-off point of 1 mm for indicating a CRH, which is substantially smaller than what has been suggested in previous reports[28 ]. However, these data should be interpreted cautiously because they were calculated based on patients who underwent a right colectomy according to ENETS guidelines indications and thus, the sample is biased. Furthermore, no patients with mesoappendix invasion in that study had recurrence. A recent meta-analysis reported a LNM rate of 30 .3 % when mesoappendix invasion was present and 26 .2 % when it was absent (OR, 1 .4 ; 95 %CI: 0 .8 -2 .4 )[32 ]. Also, in some works, the increased risk of LNM found on the univariate analysis disappeared on the multivariate analysis, with only size remaining as a relevant factor[5 ,8 ].

Positive margins: Although this may seem uncommon, a French multicenter study that included patients treated in non-referral centers reported a rate of 8 %[15 ]. Given the possibility that the tumor could remain in the cecum area, most authors recommend CRH in this scenario[8 ,28 ].

Vascular and lymphatic vessel involvement: This feature can be found in 11 % to 18 % of patients[5 ,8 ,28 ]. It could be particularly relevant in patients with tumors < 2 cm, in whom it could reflect a metastatic potential similar to tumors measuring > 2 cm[5 ,34 ]. On the contrary, some studies have not described a higher LNM rate, but the low incidence of this finding could limit statistical significance[1 ,8 ]. Perineural invasion has been reported in 18 % of patients[8 ], but there is no data to suggest more aggressive disease when it is present[32 ].

Tumor grade: Almost all aNETs are G1 . Less than 15 % have been described as G2 and the existence of G3 and poorly differentiated aNETs is anecdotal[1 ,28 ]. Although some works do not show a higher LNM rate in patients with a grade higher than G1 [8 ], many others describe a significant risk in up to 90 % of G2 neoplasms[28 ,35 ].

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

The main purpose of a right hemicolectomy after an appendectomy is not only to resect residual local tumor, but also to complete the regional lymph node dissection. Nodal spread of aNETs is usually through the ileocolic vessels, a territory with few anatomical variations. Laparoscopic dissection of this territory is quite a standard approach to treat right side colonic cancer. In the absence of gross central nodal involvement, a laparoscopic approach seems to be safe and could provide some benefits, namely a shorter recovery time.

OUTCOMES AFTER A COMPLETION RIGHT HEMICOLECTOMY

Postoperative complications

Patients who undergo CRH for aNETs are younger and have fewer comorbidities than typical patients with colon cancer. Nevertheless, the rate of major complications after a colectomy for aNETs ranges from 5 % to 15 %[28 ,36 ,37 ]. A systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Ricci et al[30 ] found that when performing a CRH in aNETs > 2 cm, the number needed to treat was five, while the number needed to harm was six, suggesting that the risk was similar to the possible benefit.

Survival and recurrence

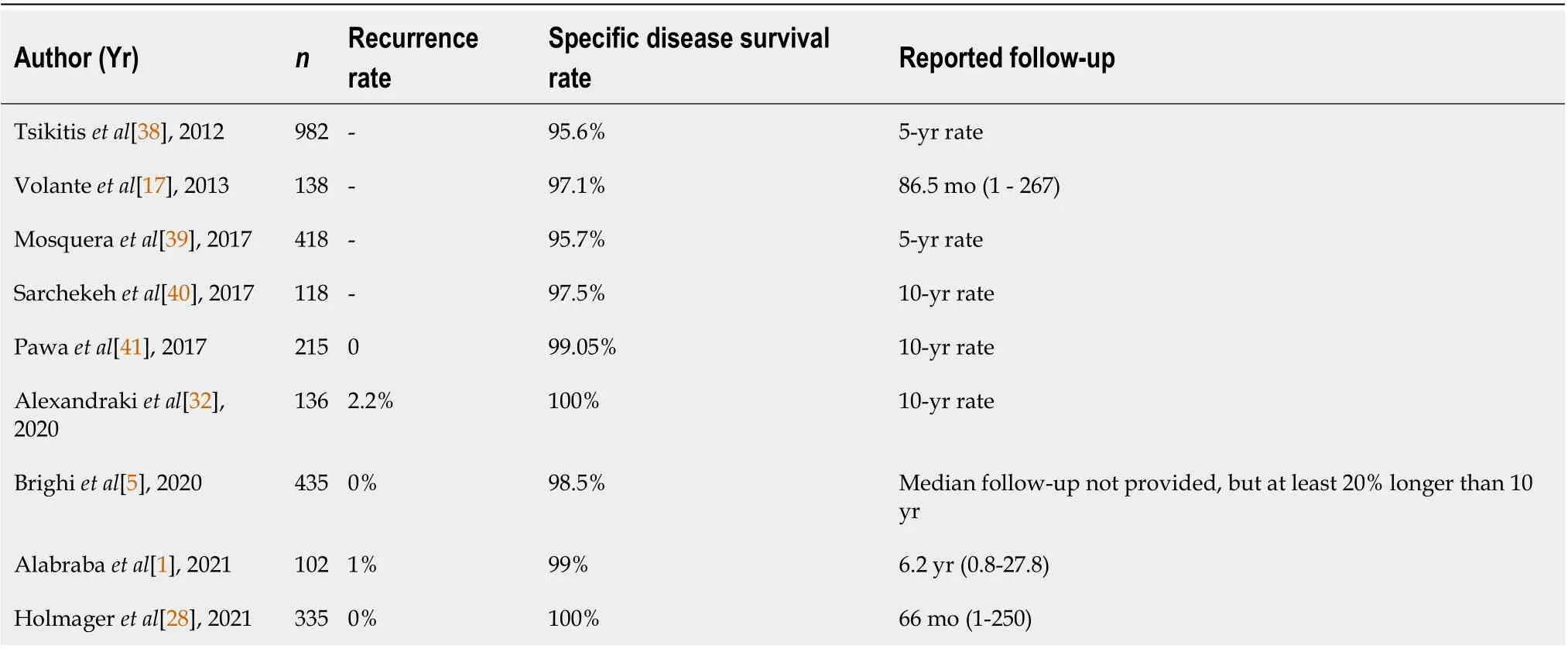

It is important to emphasize that in general, these patients have an excellent prognosis, with survival rates close to 100 % at 10 years of follow-up. Table 2 summarizes the literature on recurrence and survival rates in this type of tumor[38 -41 ].

Although several studies agree that 2 cm is a reliable cut-off point for a colectomy, others have shown that a simple appendectomy offers comparably good results in tumors > 2 cm[29 ]. For example, in the classic work by Moertelet al[42 ], only one patient treated with an appendectomy out of 12 experienced recurrence, and it occurred 29 years after the initial appendectomy. This patient then underwent a right hemicolectomy, after which he remained disease-free 17 years later. Such data could lead us to speculate whether there is a decrease in overall survival by waiting to confirm the presence of lymphadenopathy instead of performing "prophylactic" CRH. Similarly, Grothet al[43 ] performed an appendectomy alone on 34 of 122 patients with aNETs > 2 cm and there was no difference in survival compared to patients who underwent a right hemicolectomy. Controversy mainly arises in patients with aNETs between 1 to 2 cm. In these patients, all studies suggest that survival is similar after either an appendectomy or a CRH.

While most studies report features associated with LNM and recommend CRH when its presence is possible, there is a dearth of data regarding its influence on patient survival. A recent meta-analysis did not find any difference in disease-specific survival at five or ten years in patients with or without LNM(100 % in both groups for five years and 95 .6 % vs 99 .2 % for ten years)[32 ]. It is clear the extremely long course of these tumors makes it difficult to evaluate overall survival.

An interesting study on how surgical technique may influence patient survival is a review of the National Cancer Database performed by Helleret al[44 ]. Their work described 3198 cases of aNETs and found that 32 .4 % of those smaller than 2 cm were treated with a right hemicolectomy and 31 .5 % of those larger than 2 cm were treated with a simple appendectomy. There were no differences in survival between the groups according to surgical procedure.

Quality of life

In addition to questions regarding a survival benefit after CRH in aNETs < 2 cm, its influence on patients’ quality of life must also be considered. This topic has recently been evaluated in a multicenter study from five ENETS centers of excellence in which the health-related quality of life European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer-QLC-C30 was administered to 79 patients with aNET[29 ]. While the patient group did not have lower scores compared to matched healthy controls,patients who underwent CRH (30 patients) had worse scores on social functioning, diarrhea, and financial difficulties compared to patients treated only with an appendectomy (49 patients).Additionally, no benefit in disease-free survival was observed after CRH.

FOLLOW-UP

There are no specific recommendations based on randomized trial data on follow-up after resection of an aNET and no adjuvant therapy is recommended after complete resection of a well-differentiated midgut NET. Several international guidelines include strategies for follow-up based on tumor size and the surgery performed[9 ,10 ,45 ].

Patients with tumors < 1 cm or from 1 to 2 cm without poor prognostic factors do not generally require further routine surveillance and tests should only be ordered if they are clinically indicated[9 ,45 ]. ENETS guidelines extend this recommendation to patients with tumors treated with a hemicolectomy without evidence of lymph node involvement[10 ].

Patients with tumors from 1 to 2 cm with poor prognostic factors who do not undergo a hemicolectomy or those with tumors > 2 cm should be followed-up on every three to six months in the first year after resection and then every six to 12 mo for at least seven years. Due to the slow growth pattern of these tumors, lifelong monitoring for potential recurrence must be provided[9 ,10 ].

In the case of candidates for surveillance, follow-up should consist of a medical history and physical examination. In addition, tumor markers (including 5 -HIAA and CgA) and abdominal imaging by means of a CT or MRI scan should be considered. The role of a colonoscopy or transabdominal ultrasound has not been established in these patients[9 ,10 ,45 ] (Table 3 ).

Table 2 Summary of published data on appendiceal neuroendocrine tumor recurrence and survival

Table 3 Follow-up recommendations according to European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society and North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society

SRS imaging is not routinely recommended for restaging in the initial follow-up after resection with curative intent and should be performed only for restaging at the time of clinical or laboratory progression without progression on conventional imaging tests[46 ].

TREATMENT IN ADVANCED DISEASE

The initial evaluation for patients with metastatic relapse or progression should include conventional imaging tests (CT or MRI scan), functional imaging tests with SRS-PET, and an assessment of carcinoid syndrome. All patients with advanced aNETs should be referred to a center with experience in neuroendocrine neoplasms and evaluated by a multidisciplinary tumor board.

Systemic treatment strategies for advanced or metastatic disease are similar to what is indicated for other midgut NETs. SSAs are usually the first-choice systemic therapy for symptomatic control in functional tumors. Antiproliferative activity has been demonstrated in two placebo-controlled randomized trials: The PROMID study with octreotide LAR 30 mg/28 d[47 ] and the CLARINET study with lanreotide autogel 120 mg/28 d[48 ].

Patients with a positive SRS functional imaging test are potential candidates for peptide receptor radionuclide therapy after progression on somatostatin analogs. Currently, lutetium 177 is approved for GEP-NETs in light of data from the NETTER-1 trial on midgut NETs[49 ].

Treatment with targeted therapies is based on the mTOR inhibitor everolimus. The RADIANT-4 trial confirmed the efficacy of everolimus in non-functioning NETs of gastrointestinal and pulmonary origin,including midgut NETs[50 ].

In addition, for patients who need regional control of liver metastasis due to carcinoid syndrome or for disease control in cases with liver-limited disease, locoregional therapies should be evaluated. Liverdirected therapies include ablative techniques such as percutaneous radiofrequency ablation or particle embolization with or without cytotoxic agents or radioactive microspheres. Chemotherapy is not routinely recommended and is reserved only for patients with progressive disease along with other strategies or for patients with rapidly progressing disease[51 ].

DISCUSSION

A hemicolectomy after the incidental finding of an aNET during an appendectomy is currently indicated depending on the stratified risk of relapse. There is consensus on not performing a hemicolectomy in tumors that measure < 1 cm, as these patients are considered cured and do not even require follow-up. On the other hand, a hemicolectomy should always be considered for tumors that measure > 2 cm.

Indications for tumors between 1 -2 cm are where the controversy lies. Current guidelines give recommendations based on risk factors beyond tumor size: mesoappendix invasion, positive margins,vascular and lymph node involvement, and tumor grade. However, these recommendations are not supported with enough high-quality evidence.

A decision regarding a hemicolectomy in an aNET between 1 and 2 cm should be discussed by a multidisciplinary tumor board in expert centers. The opinions of pathologists, surgeons, gastroenterologists, endocrinologists, radiologists, medical oncologists, and nuclear medicine specialists should be taken into consideration before making a recommendation. Long-term issues related to a hemicolectomy should be discussed with the patient, particularly with those who are younger.

This narrative review aims to examine current evidence that is mainly based on clinical guidelines,providing the framework for a multidisciplinary tumor board discussion. The main limitation is a lack of prospective studies, an unmet need that should be addressed in the future. Indeed, at present, the SurvivApp study aims to analyze distant metastasis and long-term outcomes in patients after complete resection of an aNET. It aims to recruit 700 participants over ten years and divide them into two cohorts of retrospective and prospective cases. Its primary objectives are related to tumors measuring 1 -2 cm and include clinically relevant relapse, clinically relevant mortality, and frequency of distant metastasis[52 ].

CONCLUSION

Decisions related to the indication of a hemicolectomy and follow-up should be made by a multidisciplinary tumor board at expert centers in order to offer each patient an individualized treatment approach.The factors that should be discussed include tumor size, mesoappendix invasion, positive margins,vascular and lymphatic vessel involvement, and tumor grade. Prospective studies regarding optimal treatment for aNETs are an unmet need in the NET field and should be addressed in the future.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Muñoz de Nova JL, Hernando J, Sampedro Núñez M, Vázquez Benítez GT, Triviño Ibáñez EM conceived the review and conducted the literature review; Muñoz de Nova JL, Hernando J, Sampedro Núñez M, Vá zquez Benítez GT, Triviño Ibáñez EM, del Olmo García MI, Barriuso J analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript;Capdevila J, Martin-Perez E contributed to the design of the paper and carried out a critical review of the text; all authors have read and approve the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest statement:Authors declare no conflict of interests for this article.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4 .0 ) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4 .0 /

Country/Territory of origin:Spain

ORCID number:José Luis Muñoz de Nova 0000 -0003 -1439 -5632 ; Jorge Hernando 0000 -0002 -0929 -7360 ; Miguel Sampedro Núñez 0000 -0002 -0089 -4046 ; Greissy Tibisay Vázquez Benítez 0000 -0002 -9442 -9064 ; Eva María Triviño Ibáñez 0000 -0001 -6604 -6608 ; María Isabel del Olmo García 0000 -0002 -4278 -2624 ; Jorge Barriuso 0000 -0002 -5641 -9105 ; Jaume Capdevila 0000 -0003 -0718 -8619 ; Elena Martín-Pérez 0000 -0002 -4933 -738 X.

S-Editor:Zhang H

L-Editor:A

P-Editor:Zhang H

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年13期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年13期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Therapeutic drug monitoring in inflammatory bowel disease: At the right time in the right place

- Endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer: Towards a global understanding

- Generic and disease-specific health-related quality of life in patients with Hirschsprung disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Locoregional therapies and their effects on the tumoral microenvironment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- Increased prognostic value of clinical–reproductive model in Chinese female patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- Comparison of the performance of MS enteroscope series and Japanese double- and single-balloon enteroscopes