Current insights on haemorrhagic complications in percutaneous nephrolithotomy

Sujeet Poudyal

Department of Urology and Kidney Transplant Surgery, Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital,Kathmandu, Nepal

KEYWORDS Percutaneous nephrolithotomy;Bleeding;Embolisation;Renal stone;Puncture

Abstract Objective: Percutaneous nephrolithotomy(PCNL)is the standard procedure for the management of large and complex renal stones.Blood loss during PCNL may occur during puncture, tract dilatation, and stone fragmentation.Therefore, despite recent advances in PCNL,haemorrhagic complication still occurs.This study aims to enlighten on various aspects of haemorrhagic complication in PCNL, mainly focusing on risk factors and management of this dreadful complication.Methods: Literature search for the study was carried out using advanced search engines like PubMed, Cochrane, and Google Scholar, combining keyword “percutaneous lithotomy” with other keywords like “bleeding”, “haemorrhage”, “complications”, “stone scoring systems”,“mini-PCNL vs.standard”,“dilatation techniques”,“supine vs.prone”,“USG-guided”,“endoscopic combined intra-renal surgery”, “papillary vs.non-papillary puncture”, “bilateral”, and“angioembolization”.The articles published between January 1995 and September 2020 were included for the review.Results: A total of 3670 articles published from January 1995 to September 2020 were screened for the review.Although not consistent, multiple studies have described various preoperative and intraoperative risk factors related to significant bleeding in PCNL.Identification of these risk factors help urologists to anticipate and promptly manage haemorrhagic complications associated with the procedure.A conservative approach suffices to control bleeding in most cases; nevertheless, bleeding can be life-threatening and few still need surgical intervention in the form of angiographic embolisation or open surgical exploration.Conclusion: As hemorrhagic complication in PCNL is associated with considerable morbidity and mortality, prudent intraoperative decision and postoperative care are necessary for its timely prevention, detection, and management.

1.Introduction

History of the percutaneous approach to the kidney to drain obstructed renal units dates to 1955[1].This approach was later employed for the removal of renal stones in 1976 [2].Percutaneous nephrolithotomy(PCNL)has now become the standard procedure for the management of large stones and has largely surpassed open surgical techniques for renal stone management [3].The primary goal of treatment is absolute clearance of the stone with minimal complications.Despite recent advances, complications are still common [4-6].The Clinical Research Office of the Endourological Society(CROES)PCNL Global Study reported complications in about one-fifth of the patients[5].PCNL is a controlled Grade IV renal injury,and blood loss may occur during puncture, tract dilatation, and stone disintegration[7].Therefore, bleeding, in particular, is a concerning sequela that requires prompt control and management of PCNL.There is a wide variation in the rate of blood transfusion for bleeding in PCNL with literature describing up to 53% rate of transfusion [8].Although a conservative approach suffices to control most bleeding after PCNL, a proportion of patients (0.5%-2.4%) have severe haemorrhage that necessitates surgical intervention [8-12].

This review aims to enlighten on various aspects of haemorrhagic complication in PCNL,mainly focusing on risk factors and management of this dreadful complication.Literature search for this review was carried out using advanced search engines like PubMed, Cochrane, and Google Scholar, combining keywords “percutaneous lithotomy”with other keywords like“bleeding”,“haemorrhage”,“complications”, “stone scoring systems”, “mini-PCNL vs.standard”, “dilatation techniques”, “supine vs.prone”,“USG-guided”, “endoscopic combined intra-renal surgery”,“papillary vs.non-papillary puncture”, “bilateral”, and“angioembolization”.A total of 3670 articles published from January 1995 to September 2020 were screened for the review.

2.Factors affecting bleeding in PCNL

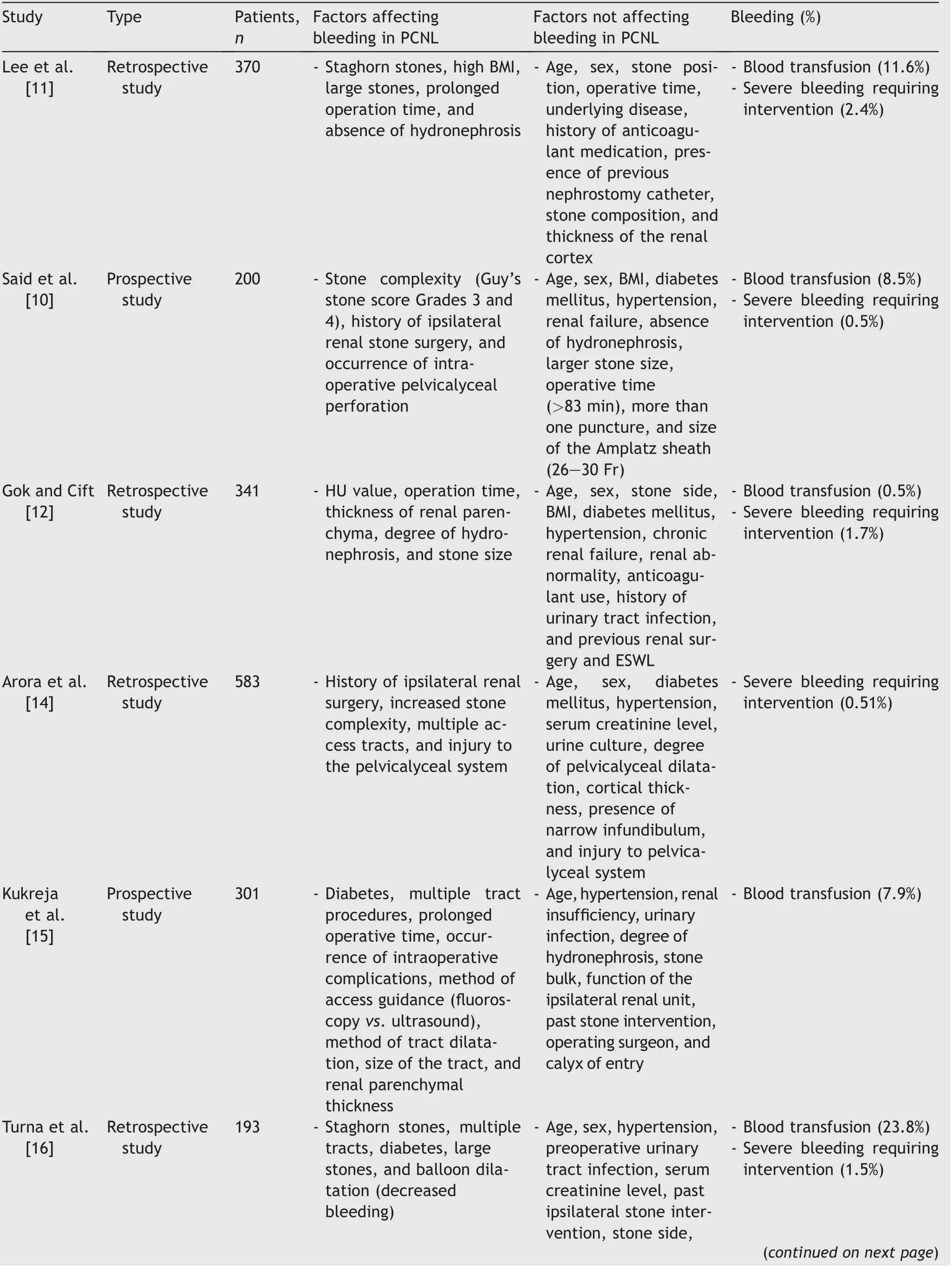

Certain factors related to patients, stones and procedures,are of value in predicting bleeding after PCNL.Many studies(as shown in Table 1) have predicted various factors responsible for bleeding complications and these factors are not consistent in all studies.

Table 1 (continued)

Table 1 (continued)

Table 1 Studies showing factors affecting haemorrhagic complications in PCNL.

2.1.Patient-related factors

The role of body mass index (BMI) in increasing haemorrhagic complications after PCNL has been reported by Lee et al.[11].However, many studies did not show BMI to be the factor associated with bleeding in PCNL [10,12].Yesil et al.[13] divided 360 patients into four groups consisting of primary PCNL patients, patients with a history of previous open surgery, those with a history of previous PCNL surgery, and the last group with a history of previous extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy (ESWL).The study demonstrated that previous ipsilateral open surgery increased the risk of postoperative bleeding.This finding was also supported by the studies conducted by Said et al.[10] and Arora et al.[14].Conversely, Kukreja and his colleagues [15] reported that past stone surgery was associated with decreased bleeding in PCNL.Thinner renal parenchyma,associated with previous surgery was speculated to be the cause of decreased bleeding.Diabetes mellitus has been studied as one of the factors responsible for bleeding after PCNL [16-18].It seems that the association between diabetes and arteriosclerosis could explain the higher bleeding incidence during percutaneous access.By contrast, the association between diabetes and post-PCNL bleeding has been refuted by many studies [10,14].Another factor that has been identified as a risk factor for post-PCNL haemorrhage is preoperative urinary tract infection [19-21].The presence of an underlying infection may result in inflammation of the renal parenchyma,making parenchyma more friable and delaying the formation of firm blood clots at the vascular puncture site.A retrospective study by Zehri et al.[22] showed a female gender and chronic renal failure to be the trigger factors for blood transfusion.The low preoperative haemoglobin level in the female population, decreasing the threshold for transfusion, and increasing bleeding tendency in patients with chronic renal failure has been speculated to be the reasons for increasing blood transfusion rate after PCNL.However,many studies did not consistently supported their findings [10,11,14-17].Furthermore, advanced age and stone laterality have not been found to be the predictors of bleeding in PCNL [9-11,14-18].Similarly, the use of anticoagulant has not been shown to increase bleeding in PCNL[17].

Various kidney-related anatomical factors have been related to bleeding in PCNL.Lee and his colleagues [11]depicted the role of hydronephrosis as one of the predictors of bleeding in PCNL.Similar finding was depicted by the study done by Gok and Cift [12].Senocak et al.[23] evaluated 105 renal units of pediatric patients and found that the degree of hydronephrosis, number of tracts, and operative time were the determining factors influencing blood loss during pediatric PCNL.A lesser degree of hydronephrosis along with increased parenchymal thickness was associated with a higher blood transfusion rate.A greater degree of hydronephrosis allows easier access to the pelvicalyceal system as well as tract dilatation.Multiple studies have demonstrated that PCNL in the horseshoe kidney was safe with no increased risk of bleeding [24,25].Similarly, the renal anomaly was not found to be a significant predictor for bleeding in most studies [12,23,26].

2.2.Stone related factors

Kessaris et al.[9] in their study of 17 patients, observed that eight patients who needed angioembolization had staghorn stones.Similarly, studies by Srivastava et al.[27]and Arora et al.[14] showed that the size of stones and stone complexity were important factors for severe vessel injury.Turna et al.[16] reported that staghorn stones and stone size served as predictive factors of intraoperative bleeding in 193 patients who underwent PCNL.With an increase in the stone size,there is an obvious increase in the maneuvering performed within the pelvicalyceal system,which could, in turn, lead to an increased incidence of injury of the renal parenchyma.Increased stone burden is likely to increase the number of tracts to clear the stones and prolong the surgery as well.The association between stone density and bleeding was explained by Gok and Cift[12] in their study which showed that the risk of bleeding increased with increasing Hounsfield units of stone.The likely reasons for increased bleeding are prolonged operative time and increased trauma during stone fragmentation associated with increased density of the stone.

Different scoring systems and nomograms have been developed to stratify and standardize the complexity of renal stone.They have been found to predict not only the stone clearance but also the complications in PCNL.Bozkurt and his colleagues [28] in their study of 437 PCNL reported that Guy’s stone score (GSS) and CROES nomogram had comparable accuracy in predicting post-PCNL complications including bleeding.Another study by Yarimoglu et al.[29]in 262 patients reiterated that GSS and CROES nomograms were significantly associated with post-PCNL bleeding.Other studies done by Labadie et al.[30]and Okhunov et al.[31] showed that the S.T.O.N.E (stone size[S], tract length[T], obstruction [O], number of involved calyces [N], and essence or stone density [E]) nephrolithometry score correlated with PCNL complications including bleeding.Similarly, Rathee et al.[32] reported both GSS andS.T.O.N.E score predicted PCNL bleeding.Biswas et al.[33]compared GSS, S.T.O.N.E scores, and CROES nomograms,and concluded that all three scoring systems were significantly associated with estimated blood loss in PCNL.

2.3.Intraoperative factors

2.3.1.Number of punctures

Turna et al.[16] reported that the number of calyceal punctures was one of the predictive factors of intraoperative bleeding in PCNL.In several series,the number of percutaneous tracts was related to higher bleeding and transfusion rates [16,26,34,35].It is a logical consequence of the number of vascular injuries caused by each tract.A greater number of percutaneous tracts are needed for larger, complex, and multiple stones.Currently, the use of flexible nephroscope together with endoscopic combined intrarenal surgery (ECIRS) allows the management of large volume stones and access to all renal cavities through only one percutaneous tract.

2.3.2.Size of the tract

Hamamoto et al.[36] demonstrated that the decrease in hemoglobin during mini-ECIRS and mini-PCNL was significantly lower than that during conventional PCNL.Yamaguchi et al.[37] also reported that as the tract size increased, bleeding complications increased.In his study,blood transfusion rates were 1.1%, 4.8%, 5.9%, and 12.1%for tract sizes of less than 18 Fr, 24-26 Fr, 27-30 Fr, and 32-34 Fr, respectively.A study from PCNL CROES database has reported that when larger sheaths were compared with an access sheath ≤18 Fr, larger access sheaths of 24-26 Fr were associated with 3.04 times increased odds of bleeding, and access sheaths of 27-30 Fr were associated with 4.91 times increased odds of bleeding [38].Similarly, multiple studies have found that standard PCNL was associated with a higher rate of blood transfusion compared to mini-PCNL as shown in Table 2 [39-44].

Table 2 Studies comparing blood loss in standard PCNL vs.mini-PCNL.

2.3.3.Operative time

Lee et al.[11] and Huang et al.[19] pointed out the impact of prolonged intraoperative time in augmenting bleeding complications of PCNL.Kukreja et al.[15] in their prospective study found that multiple tracts, prolonged surgical time, and intraoperative complications were significantly associated with increased renal haemorrhage during PCNL procedure.It is obvious that as the operative time increases, it prolongs trauma to the renal parenchyma and bleeding continues through the tract.Furthermore, the ongoing instrument manipulation also aggravates the injury of the pelvicalyceal system leading to increased blood loss.

2.3.4.Selection of calyx for puncture

El-Nahas et al.[26] reported that the factors significantly associated with bleeding requiring superselective angioembolization were multiple tracts, upper calyceal puncture, staghorn stone, solitary kidney, and the experience of the operating surgeon.The long and oblique trajectory during upper calyceal puncture and the thick parenchyma of the hypertrophied solitary kidney may be the possible reasons for significant bleeding.Upper calyceal access was also a predictor for angioembolization in PCNL in the study conducted by Jinga and his colleagues [21].In the study carried out by de Fata et al.[45], the variables significantly associated with bleeding in supine PCNL were multiple punctures and the approach through the middle renal calyx, which was carried out in 20% of patients.In subcostal punctures during supine PCNL, an oblique and long tract to the middle calyx was the likely cause for a high possibility of parenchymal and vascular injury.In contrast to the study by El-Nahas et al.[26], Tan et al.[46] stated that inferior calyceal access was associated with severe postoperative bleeding and they speculated the reason to be the oblique and long tract required for inferior calyceal access.Studies by El-Nahas et al.[26] and Jinga et al.[21]did not show the significance of supracostal puncture in bleeding complications when compared to subcostalpunctures.Thus,it is not the calyx or site of puncture, but the trajectory of the access, which determines the haemorrhagic complications in PCNL.The longer and more oblique the tract are, the more it traverses the renal parenchyma and blood vessels leading to increased bleeding.

2.3.5.Papillary vs.non-papillary puncture

The fornix of the papilla is the preferred site for puncture to make access to the pelvicalyceal system in PCNL.Sampaio and his colleagues[47]studied the impact of puncture through the fornix and infundibulum in the superior, middle, and inferior regions of the kidney using threedimensional kidney models from 62 cadaveric kidneys and demonstrated 67.6%, 38.4%, and 68.2% vascular lesions in the upper, mid, and lower infundibular punctures, respectively compared to 7.7%, 7.1%, and 8.3% vascular lesions in upper, mid, and lower forniceal punctures, respectively[47].When puncture is done through the infundibulum,there is a risk of injury and significant bleeding from the infundibular vessels which surround the infundibulum.The risk of injury is again aggravated by dilatation and manipulation of the access sheath during PCNL.Kim et al.[48] demonstrated that incorrect renal puncture was related to severe bleeding requiring angioembolization after PCNL.The puncture was defined as being correct if the fornix or papilla of the posterior calyx was punctured and the trajectory of the tract was within 20°posterior to the frontal plane of the kidney (i.e., within Bro¨del’s line).Puncture correctness was assessed using postoperative computerised tomogram (CT) scans.Conversely, Kallidonis and his colleagues[49]in their randomized controlled study consisting of 55 patients reported similar blood loss and transfusion rates when the infundibular approach was compared with the papillary approach for the posterior middle renal calyces.

2.3.6.Methods of tract dilatation

The study conducted by Turna et al.[16] observed decreased bleeding with balloon dilatation when compared to Amplatz dilatation.By contrast, Pakmanesh and his colleagues [50] in their randomised controlled trial of 66 patients reported that both Amplatz and balloon dilatation were comparable in regard to post-PCNL bleeding.Yamaguchi et al.[37] in their PCNL global study reported that balloon dilatation had significantly higher bleeding(9.4% vs.6.7%) and more transfusion rate (7.0% vs.4.9%)compared with telescopic/serial dilatation.However, dilatation methods did not turn out to be significant in multiple regression analysis as a predictor of bleeding and transfusion in PCNL [37].A systematic review and meta-analysis of seven randomised controlled trials noted a significant decrease in postoperative haemoglobin of about 2.3 g/L with similar transfusion rates in one-shot dilatation when compared with serial dilatation [51].

2.3.7.Drainage procedures (standard vs.tubeless vs.totally tubeless)

A randomised controlled study conducted by Mishra et al.[52], comparing standard and tubeless PCNL, reported equivalent bleeding complications in both drainage procedures.Another study by Istanbulluoglu et al.[53]comparing standard, tubeless, and totally tubeless PCNL showed no difference in haemoglobin level change and blood transfusion.Tubeless percutaneous nephrolithotomy has been found to be safe and efficacious in uneventful procedures, regardless of particular circumstances like obese and paediatric patients, simultaneous bilateral procedures, supracostal access, and in renal units with coexisting anatomical anomalies [54].In patients with no major intraoperative bleeding and pelvicalyceal perforation,tubeless and totally tubeless procedures have been found to be safe [55].Multiple randomised controlled trials showed no significant difference in blood loss with the use of hemostatic agents (fibrin sealant, gelatin sponge, or oxidized cellulose)in tubeless PCNL[56-58].A randomised controlled study carried out by He et al.[59] compared standard nephrostomy tube placement with a modified nephrostomy tube covered in absorbable haemostatic gauze.The modified nephrostomy resulted in a significant decrease in blood loss; although not significant, it was associated with fewer blood transfusion rates and angioembolization.

2.3.8.Fluoroscopy vs.ultrasound-guided (USG) renal access

A matched case analysis from the international CROES database comprising 453 procedures in each group of fluoroscopy and USG-guided renal access for PCNL showed that postoperative haemorrhage and transfusions were significantly higher in the fluoroscopy group.When adjusted for access sheath size and multiple tracts, the difference in bleeding rate did not turn out to be significant [38].Multiple studies did not observe a significant difference in post-PCNL bleeding when either fluoroscopic or USG-guided access was used [60-65].A systemic review and metaanalysis done by Yang et al.[66] reported a comparable drop in haemoglobin and transfusion rate in both fluoroscopic and USG-guided access.Contradictorily, the study done by Kukreja et al.[15] showed that USG-guided access was significantly associated with decreased blood loss than fluoroscopy-guided access.During puncture, Doppler USG can confirm the path of blood vessels in the renal parenchyma and prevent injury to these blood vessels leading to decreased bleeding in PCNL.

2.3.9.Use of endoscopic combined intra-renal surgery(ECIRS)

Hamamoto et al.[36] retrospectively compared ECIRS,mini-PCNL, and conventional PCNL, and found out a significant decrease in haemoglobin drop in ECIRS and mini-PCNL group.A randomised controlled trial comparing minimally invasive percutaneous nephrolithotomy versus endoscopic combined intrarenal surgery with a flexible ureteroscope for partial staghorn calculi did not show a significant difference in blood loss [67].Another retrospective study by Leng et al.[68] comparing 87 patients grouped into mini-PCNL and mini-PCNL combined with flexible ureterorenoscopy in the oblique supine lithotomy position showed a significantly higher haemoglobin drop in the mini-PCNL group.In complex and large renal stones,ECIRS decreases bleeding by preventing the need for multiple tracts and by reducing the manipulation of the Amplatz sheath and the nephroscope during stone clearance.

2.3.10.Supine vs.prone PCNL

Multiple randomised controlled trials and meta-analyses comparing supine and prone PCNL reported nonsignificant differences in bleeding complications [69-72].A metaanalysis done by Falahatkar et al.[73] included 13 studies,out of which five were retrospective in nature,and it depicted a lower blood transfusion rate in the supine group compared to the prone group (5.0% vs.6.3%;p=0.01).A recent meta-analysis of 12 randomised controlled trials, comprising 583 and 585 cases in supine and prone group, respectively, reiterated the similar transfusion rates between supine and prone PCNL (6.0% vs.5.3%; p=0.58) [70].

2.3.11.Experience of surgeons

It is obvious that increased experience in any surgery increases the success rate and diminishes the complications related to surgery.It applies well in PCNL, as PCNL is said to have a steep learning curve [74-76].El-Nahas et al.[26] highlighted the importance of the experience of the endourologist in their study, and concluded that an experienced endourologist should perform PCNL in patients who are at risk for severe bleeding, such as those with a solitary kidney or staghorn stone.Conversely, multiple studies did not find a significant correlation of the experience of the surgeon with bleeding in PCNL [15,22,23].

2.3.12.Bilateral synchronous vs.staged approach

In the retrospective evaluation conducted by Srivastava et al.[27], comprising 1854 patients undergoing PCNL, 86 bilateral simultaneous PCNL procedures were performed,and the study showed that the bilateral simultaneous procedure was not a parameter predicting vascular complications of PCNL.A systematic review by Jones et al.[77] comparing bilateral synchronous PCNL and staged PCNL reported a non-inferior safety profile of bilateral procedures.Bilateral simultaneous PCNL was found to be technically demanding, requiring careful patient selection, counselling, and centers with large case volumes.After completing a unilateral procedure in the patient,the criteria considered for deferring contralateral surgery were: More than two tracts on the initial side,severe haemorrhage, haemoglobin drop >30 g/L or level<11 g/L,arterial oxygen saturation <95%,pH <7.35,serum sodium <128 mg/mL, systolic pressure <100 mmHg(1 mmHg=0.133 kPa), operative time >180 min, or any other unforeseen complication.

3.Management

Haemorrhagic complications of PCNL may occur intraoperatively,early postoperatively within hours and days,or late postoperatively in weeks and months.Intraoperative bleeding can occur during puncture, tract dilatation, instrument manipulation, or stone fragmentation.Intraoperative bleeding may result from traumatised renal parenchyma or injury to the perinephric vessels.It mostly occurs in interlobar and segmental renal vessels.Injury to the main renal vessels and great vessels may lead to acute massive haemorrhage, but they are relatively uncommon,occurring in 0.5% of cases [78].Injury to the adjacent organs like liver and spleen and haemothorax from a supracostal puncture,although uncommon,should be ruled out as potential sources of bleeding in PCNL [79,80].Overall, transfusion rates in PCNL have declined from 53%to less than 10% in recent series, with most managed conservatively and only a few requiring surgical interventions as shown in Table 1 [15].Late postoperative bleeding with its incidence of 0.8%-2.6% is mostly due to arterial pseudoaneurysm and arteriovenous fistula (AVF)[81].The renal collecting system should be accessed along a line that passes through the fornix and the infundibulum of a posteriorly oriented calyx.This short and straight path traverses less parenchyma compared to an anterior puncture and leads the tract through the avascular Brodel’s line avoiding infundibular vessels.

Bleeding can be covert, concealed as retroperitoneal haematoma or overt,seen through the tract,or in the form of haematuria.Bleeding can be arterial or venous.Venous bleeding is usually mild and most of the time can be managed conservatively.It is wise to stage the procedure with a nephrostomy tube if intraoperative bleeding is severe enough to blind the vision.Intraoperatively, bleeding can be controlled by the use of a large-bore nephrostomy tube which should be clamped for 4-8 h.If the urine from Foleys catheter clears out, a trial of declamping can be attempted,otherwise,it should be clamped for 24-48 h for persistent bleeding [20,82-84].Other options that have been used instead of the nephrostomy tube are balloon dilator, Kaye nephrostomy tamponade catheter, or a nephrostomy tube covered with absorbable haemostatic gauze [59,85,86].A Kaye tamponade catheter can also be applied later if clamping the large bore nephrostomy tube does not sufficiently control bleeding.Intravenous hydration along with administration of mannitol in a hemodynamically stable patient also leads to swelling of the kidney with tamponade of the tract [9,82,87].The use of tranexamic acid was found to be associated with decreased blood transfusion rate in PCNL [88,89].

Postoperatively, the patient should be stringently monitored including their vitals, urine output, serial haemoglobin, and arterial blood analysis as needed.Haematuria and pallor should be looked for, and the abdomen should be examined for retroperitoneal/intraabdominal collection or the presence of urinary retention due to clot.Furthermore, chest examination should also be performed to rule out haemothorax in those with supracostal access[79].If easily available, it is better to incorporate USG in clinical examination.Shock accompanied by oliguria/anuria with metabolic acidosis and significant drop in haemoglobin needs resuscitation with fluid and blood transfusion, and should prompt the urologist to be vigilant for urgent surgical intervention [87,90].The algorithm shown in Fig.1 outlines the management of significant haemorrhage associated with PCNL.

Discreet monitoring is warranted in major bleeding,which is indicated by a drop in haemoglobin by 2 g/dL and/or in need of a transfusion of two or more packed red blood cells [91,92].Likewise, massive haemorrhage,defined by transfusion of four or more packed red blood cells within 6 h, requires urgent surgical intervention[20,91,92].Moreover, recurrent or continuous bleeding with a drop in haemoglobin by 3 g/dL and/or fall ofhaematocrit less than 30% may be an early indicator of the need for surgical intervention [16,91,93,94].Metabolic acidosis, hypothermia, and coagulopathy form the lethal triad of massive haemorrhage, and utmost caution should be taken to prevent and treat this vicious cycle [95].Intraoperative blood loss may be estimated by measuring haemoglobin concentration and volume of the irrigated fluid and urine [96].The value may underestimate the blood loss in the presence of a retroperitoneal/intraabdominal haematoma, haemothorax, or clots inside the urinary bladder.Haemoglobin drop has been widely used as a guide to estimate perioperative blood loss which again can be correlated with maximal allowable blood loss,especially in the pediatric population,to serve as a marker for blood transfusion [97,98].However, in the setting of acute haemorrhage, the drop in haemoglobin is a poor marker of blood loss.Therefore, proper clinical examination, regular monitoring of vitals and urine output, along with arterial blood analysis should not be overlooked[99,100].

Figure 1 Algorithm for the management of significant haemorrhage in PCNL.CT, computerised tomogram; DSA, digital subtraction angiography; PCNL, percutaneous nephrolithotomy;

Haemodynamic instability after resuscitation requires either urgent renal conventional angiography with superselective embolisation of the bleeding vessel or urgent open surgical exploration if an angiogram is not available[82,101].A study by Aminsharifi et al.[102]described eight cases who underwent urgent surgical exploration for massive haemorrhage after PCNL.Two cases underwent partial nephrectomy, whereas renorrhaphy sufficed in all others.With the same principles followed during surgical exploration in patients with high-grade renal trauma,renal pedicle control should be the first approach during exploration such that the operation could be done in a bloodless field and the kidney could be salvaged.Nephrectomy may be inevitable as a part of damage control surgery in an exsanguinating and haemodynamically unstable patient in whom kidney salvage is not possible [26].Those having gross haematuria should be managed with continuous bladder irrigation to prevent clot formation and once clot retention occurs, if bladder washouts fail,cystoscopy with clot evacuation is needed.

CT/magnetic resonance (CT/MR) renal angiography is indicated in haemodynamically stable patients if there is a need for repeated transfusions due to ongoing bleed,repeated clot evacuation, continuing fall in haematocrit,and persistent hematuria.As CT renal angiography is noninvasive and 86%-100% sensitive compared to renal conventional/digital subtraction angiography (DSA), it helps in planning the intervention in haemodynamically stable patients [103].Renal DSA remains the gold standard for the diagnosis and treatment of renal artery lesions and should not be delayed in cases of massive or persistent haemorrhage.In the presence of renal insufficiency, Doppler ultrasonography and renal DSA should be performed avoiding a contrast CT scan.The findings of vascular lesions in CT angiography and/or significant ongoing bleeding should prompt early DSA with superselective angioembolization[82].Delayed postoperative bleeding, which mostly presents with abrupt, brisk and intermittent bleeding, has been found to have vascular lesions in most cases; thus,benefits from prompt superselective angioembolization[93].The need for renal artery embolisation to control renal bleeding has been found to be 0.3%-3.9% and its success rate has been reported to be 82.7%-100%[11,14,17,26,47,81,101,104-107].Advancement in technology along with the experience of interventional radiologists has increased the success rate of renal angioembolization over time [107].The lesions in renal angiography are pseudoaneurysm, arteriovenous fistula,arteriocalyceal fistula,and active extravasation of contrast suggesting active renal haemorrhage [108].Embolisation can be performed with materials such as ethanol, metal coils, gel foam particles, and N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate[101,109].Site and accessibility of the vessel feeding the pseudoaneurysm or AVF as well as the availability of the material determine the choice of embolic material.The choice of embolic material for large aneurysms and AVF was N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate and coils, respectively, whereas gel foam was used for smaller fistula and aneurysms [110].

In the study done by Richstone et al.[107], 17% of post-PCNL haemorrhages requiring superselective angioembolization demonstrated multiple angiographic findings.Conversely, 5.3% did not show demonstrable angiographic findings resulting in haemorrhage.El-Nahas et al.[26]studied 39 patients undergoing superselective renal artery embolisation.In their study, eight showed multiple angiographic lesions and 10 required a second session of angioembolization.In those requiring second session of angioembolization,two cases did not demonstrate vascular injuries during the first session whereas eight had recurrent haemorrhage.Similarly,three cases needed urgent surgical exploration due to failure of renal angiography, out of which one required nephrectomy and one succumbed to death.Similarly,Jain et al.[111]reported failure in six outof 41 patients, out of which two required nephrectomy.A retrospective analysis by Mao et al.[106]showed that large tract size, multiple bleeding sites, and renal vascular aberration/tortuosity were significant predictors for increased risk of initial treatment failure of superselective renal angioembolization.Therefore, interventional radiologists should be aware of multiple vascular lesions during angiography,mostly in those requiring a large size tract and multiple punctures [111,112].Moreover, as renal angioembolization may sometimes fail, one should prepare for another session of renal angiography and anticipate urgent surgical intervention for persistent or recurrent bleeding.Renal angioembolization procedure in itself is not only lifesaving but also renoprotective, preserving most of the normal parenchyma.In most cases, it avoids open surgical exploration, which may even end up with nephrectomy[20,26,111].

The most common complication of renal angioembolization is postembolization syndrome that affects over 90%of patients [113].Treatment is supportive with analgesics,antipyretics,and antiemetics if required.Other serious but uncommon complications are arterial dissection and coil migration, which may result in renal infarction, infarction of distant organs, and may sometimes erode into the renal collecting system [114-116].Renal dysfunction after renal angioembolization is more marked in the solitary kidney and may be likely due to contrast-induced nephropathy and/or loss of parenchymal tissue after infarction.Superselective renal angioembolization has been found to result in 0%-30% of the parenchymal deficit in immediate followup and this deficit has been found to decrease with time[117].Long-term effect of renal superselective angioembolization appears to be safe without postinfarction deterioration of renal function and renal hypertension in most cases [118-120].

4.Conclusion

Perioperative bleeding is a worrisome complication of PCNL.With technical advancements, its incidence has decreased; nevertheless, the importance of perioperative vigilance for bleeding and its optimal management should not be underestimated.

Conflicts of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Dr.Bidur Adhikari, Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital, Nepal and Mr.Ben Lloyd,Lumary,Australia for reviewing and revising the manuscript for grammar and syntax.

Asian Journal of Urology2022年1期

Asian Journal of Urology2022年1期

- Asian Journal of Urology的其它文章

- Atypical small acinar proliferation and its significance in pathological reports in modern urological times

- Subcostal artery bleeding after endoscopic combined intrarenal surgery: Signs and treatment

- Inexpensive and combined technique: Use of suction tracheal catheter and hydrogen peroxide for the evacuation of intravesical clots

- Concurrent laparoscopic management of giant adrenal myelolipoma and contralateral renal cell carcinoma

- Management and evaluation of bladder paragangliomas

- Mini versus ultra-mini percutaneousnephrolithotomy in a paediatric population