The delivery of miR-21a-5p by extracellular vesicles induces microglial polarization via the STAT3 pathway following hypoxia-ischemia in neonatal mice

Dan-Qing Xin, Yi-Jing Zhao, Ting-Ting Li, Hong-Fei Ke, Cheng-Cheng Gai,Xiao-Fan Guo, Wen-Qiang Chen, De-Xiang Liu, Zhen Wang,*

Abstract Extracellular vesicles (EVs) from mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) have previously been shown to protect against brain injury caused by hypoxia-ischemia(HI). The neuroprotective effects have been found to relate to the anti-inflammatory effects of EVs. However, the underlying mechanisms have not previously been determined. In this study, we induced oxygen-glucose deprivation in BV-2 cells (a microglia cell line), which mimics HI in vitro, and found that treatment with MSCs-EVs increased the cell viability. The treatment was also found to reduce the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, induce the polarization of microglia towards the M2 phenotype, and suppress the phosphorylation of selective signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) in the microglia.These results were also obtained in vivo using neonatal mice with induced HI. We investigated the potential role of miR-21a-5p in mediating these effects, as it is the most highly expressed miRNA in MSCs-EVs and interacts with the STAT3 pathway. We found that treatment with MSCs-EVs increased the levels of miR-21a-5p in BV-2 cells, which had been lowered following oxygen-glucose deprivation. When the level of miR-21a-5p in the MSCs-EVs was reduced, the effects on microglial polarization and STAT3 phosphorylation were reduced, for both the in vitro and in vivo HI models. These results indicate that MSCs-EVs attenuate HI brain injury in neonatal mice by shuttling miR-21a-5p, which induces microglial M2 polarization by targeting STAT3.

Key Words: extracellular vesicles; hypoxia-ischemia; mesenchymal stromal cells; microglia; miR-21a-5p; neuroinflammation; oxygen-glucose deprivation; STAT3

Introduction

Brain injury due to neonatal hypoxia-ischemia (HI) is a major cause of death and long-term neurodevelopmental disability (Ziemka-Nalecz et al.,2017). Following HI, there is evidence that proinflammatory mediators are released, which lead to neuroinflammation; this can alter neuronal function and contributes to permanent HI-induced brain damage (Liu and McCullough, 2013; Hagberg et al., 2015). Microglia are the main effectors of neuroinflammation following HI. They can be polarized into proinflammatory M1 or anti-inflammatory M2 states (Colton, 2009), and the balance between these two phenotypes plays an important role in regulating the neuroinflammation, as well as in maintaining brain homeostasis.

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) possess broad immunoregulatory properties and have potential for treating diseases that are associated with inflammation (Bernardo and Fibbe, 2013; Teixeira and Salgado, 2020; Han et al., 2021). For example, a recent study showed that human umbilical cord-derived MSCs exert anti-diabetic effects and alleviate islet dysfunction in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes, by inducing a switch from the M1 to the M2 macrophage phenotype (Yin et al., 2018). It is thought that the immunomodulatory properties of MSCs relate to paracrine signaling (Bazzoni et al., 2020). In support of this, it has been found that MSCs stimulated by a lipopolysaccharide (LPS) secrete certain factors that affect macrophage function (Crisostomo et al., 2008; Bernardo and Fibbe, 2013). Recently,extracellular vesicles (EVs) have been recognized as an important paracrine factor produced by MSCs, which contribute to the beneficial effects of MSCs (Bazzoni et al., 2020). The EVs can be classified as small (50-100 nm), medium (100 nm-1 μm), or large (1-5 μm) (Thery et al., 2018). It has been suggested that MSCs-derived EVs promote an immunosuppressive response by promoting the polarization of macrophages from the M1 to the M2 phenotype, regulating the immature dendritic cells, and secreting anti-inflammatory cytokines (Bazzoni et al., 2020). Recent research suggests that MSCs-EVs can be used to reduce ischemic brain damage. MSCs-EVs from human Wharton’s jelly were found to protect neuronal cells against oxygenglucose deprivation (OGD)-induced apoptosis (Joerger-Messerli et al., 2018).MSCs-EVs were also found to suppress LPS-induced inflammation mediated by BV-2 cells (Thomi et al., 2019).

Studies have shown that EVs contain microRNAs (miRNAs), which are taken up by recipient cells and can affect the cell fate (Xin et al., 2012,2017). MiRNAs are a type of non-coding RNA, about 20-22 nucleotides long, which participate in the regulation of gene expression at the posttranscriptional level (Moss, 2002; Shi, 2003; Bartel, 2004). MiRNAs bind to the 3′ untranslated region (3′ UTR) of the target messenger RNA (mRNA), which can lead to mRNA degradation or translational inhibition (Bagga et al., 2005;Nohata et al., 2011). This plays a role in many biological processes, including cell proliferation and apoptosis (Ambros, 2004; Li et al., 2009; Fasanaro et al., 2010; Son et al., 2014). Previous studies have shown that miR-21a-5p, a miRNA found in MSCs-EVs from the bone marrow, is of relevance to several diseases (Cheng et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2015). For instance, it has been found that miR-21a-5p in bone marrow MSCs-EVs can improve sensory and motor functions following a cerebral hemorrhage in rats by affecting the expression of the target gene,Trpm7(Zhang et al., 2018). It has also been found that miR-21a-5p in hypoxia-preconditioned MSCs-EVs can improve the decline in cognitive function in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease, by rescuing synaptic dysfunction and regulating the inflammatory response (Cui et al., 2018).

The signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) is a transcription factor that regulates genes that are involved in the inflammatory response,and it has been found to mediate the pro-inflammatory response of microglia following various central nervous system injuries. Studies have shown that activated STAT3 can promote the transcription and expression of many genes that encode pro-inflammatory mediators, including cytokines and chemokines(Yi et al., 2007). In the case of cerebral ischemia, the neuroinflammatory process has been found to involve the abnormal activation of STAT3, and the phosphorylated STAT3 (p-STAT3) has been found to be mainly located in the brain macrophages/microglia (Yi et al., 2007).

In our previous studies, we showed that the administration of MSCs-EVs leads to neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects following HI in neonatal mice (Chu et al., 2020; Xin et al., 2020). However, the underlying mechanisms are still unknown. In the present study, we induced HI in neonatal micein vivoand oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD) mimicking HIin vitro, to explore the mechanisms underlying the anti-inflammatory effects of MSCs-EVs. As there is evidence that male and female neonates have different functional outcomes and tissue damage following HI (Sanches et al., 2015; Charriaut-Marlangu et al., 2017), the study was limited to male neonatal mice; this avoided effects of gender on the experimental results.

Materials and Methods

Animals and ethics statement

The animals in this study were purchased from the Laboratory Animal Center of Shandong University (license No. SCXK (Lu) 2019-0001). They were kept in a 12-hour light/dark cycle at 18-23°C, and they were provided with sufficient food and water during the feeding periods. All of the animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the International Guiding Principles for Animal Research from the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS), and the procedures were approved by the Animal Ethical and Welfare Committee of Shandong University (approval No.ECSBMSSDU2018-2-059) on March 2, 2018. The laboratory technicians were trained in accordance with the rules of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee Guidebook (IACUC).

HI model

In this study, male pups were used for all of the experiments. HI was induced on postnatal day 7 (P7) using the method of Rice et al., as described in our previous publication (Xin et al., 2020). To summarize, 114 C57BL/6J male mouse pups (P7) were anesthetized with isoflurane (2% for induction; 1% for maintenance) and the right common carotid artery was separated and ligated with a 4-0 non-absorbable suture. After suturing and disinfecting the skin,the pups were placed in their cages for 60 minutes before being placed in a humidified hypoxia chamber for 90 minutes (Sanyo Electric, Osaka, Japan; 8%O2+ 92% N2, 37°C). The mice were then placed in their cages and were able to continue feeding. In a sham group of 36 pups, the common carotid artery was exposed, but there was no ligation or hypoxia. Twenty-four hours after the HI or sham surgery, the mice were anesthetized, fixed in the supine position, the chest and abdomen were disinfected, and a hypodermic needle was inserted at the most obvious point of the cardiac apex beat, at a depth of about 3-5 mm. Aspiration was carried out, and if there was blood, this indicated that the needle had entered the left ventricle. The drug was then injected.

Brain water content

Three days after the HI, the brains of 28 pups were removed to measure the brain water content. For this, the left and right hemispheres were separated and weighed, and then placed in an oven to dry for 2 days (at 105°C), before being weighed again. The brain water content was then calculated, as described in a previous study (Xin et al., 2020).

Measurement of infarct volume

Three days after the HI, the whole-brain tissue (n= 28) was frozen at -20°C for 30 minutes, and then the brain tissue was cut into four slices along the coronal plane, with a thickness of about 2 mm. These slices were then immersed in 2% 2,3,5-triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC) solution (Cat#T8877-10G, MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA) at 37°C for 20 minutes.The infarct volume was then determined, as described previously (Bai et al.,2016).

Tissue collection and preparation for immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence assays

Three days after the HI, the mice (n= 4 per group) were killed, and the brains were fixed in paraformaldehyde for 24 hours at 4°C. The brains were sliced into 4 μm-thick coronal paraffin sections, for the regions -1.6 mm to -2.0 mm from the bregma, using a paraffin microtome (Thermo Fisher Scientific,Waltham, MA, USA). These were then stained for immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry assays.

The immunofluorescence assays were carried out as described in a previous study (McCullough et al., 2005). For this, the brain tissue sections were dewaxed and antigen repaired, and the slices were incubated with the following primary antibodies (Table 1) overnight at 4°C: rabbit monoclonal p-STAT3 antibody (phosphorylated transcription factor; 1:100), mouse anti-Iba-1 (a marker for microglia; 1:100), rabbit anti-CD16 (a marker for M1 microglia; 1:100), or rabbit anti-CD206 (a marker for M2 microglia; 1:100).The slices were then incubated with secondary antibodies (Table 2) for 30 minutes at 37°C: Alexa Fluor® 594 AffiniPure goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L; 1:100)and Alexa Fluor® 488 AffiniPure goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L; 1:100). Finally,DAPI staining was carried out at room temperature for 5 minutes to reveal the cell nuclei (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Jiangsu, China). Fluorescence images were obtained using Pannoramic MIDI (3D HISTECH, Budapest,Hungary).

The immunohistochemical assays were carried out as described in a previous study (Chu et al., 2019). For this, the brain slices were incubated overnight at 4°C with mouse anti-Iba-1 (1:100) primary antibody (Table 1) . The slices were then treated with enzyme-labeled goat anti-mouse/rabbit IgG at room temperature for 30 minutes. The antibody binding was analyzed using a DAB kit (Gene Tech, Shanghai, China), and the slides were observed using Pannoramic MIDI. The number of endpoints per Iba-1+(microglial) cell and the length of the cell processes in the infarct core (n= 4 per group) were determined for three microscopic fields ( 400× magnification) using Fiji software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA; Schindelin et al.,2012).

Culture and identification of MSCs

Bone marrow MSCs were harvested from 30 C57BL/6J male mice (4 weeks old), as previously described and modified (Wang et al., 2009). To summarize,the cells were washed out from the femur and tibia of the mice using a syringe with 20 needles. These were then filtered through a 70 μm filter,centrifuged at 350 ×gfor 5 minutes, suspended in a complete medium(DMEM/F-12 containing 10% fetal bovine serum [FBS], 2 mM L-glutamine,100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin; Thermo Fisher Scientific),and cultured in a CO2incubator (5% CO2) at 37°C. After 3 hours, the complete medium was replaced to remove the non-adherent cells; the medium was then replaced every 8 hours over the following 24 hours, and every 3 days thereafter. The adherent cells (passage 0) were approximately 90% confluent within 14 days and were detached by incubation in 0.25% trypsin/1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The detached cells were then cultured in the CO2incubator (5% CO2; Thermo Fisher Scientific)at 37°C, and the complete medium was replaced every 3 days. The spindleshaped MSCs at passages 5-8 were used for the experiments.

Osteogenic differentiation of MSCs

To induce osteogenic differentiation, the MSCs were seeded in a 12-well plate.When the MSCs were 70% confluent, the complete medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was replaced with an osteogenic medium (OriCellTMmouse MSCs Osteogenic Differentiation Media, Cyagen Biosciences, China) and changed every 3 days. After 3 weeks, the cells were observed under a light microscope(AXIO, Oberkochen, Germany; Wang et al., 2021).

Adipogenic differentiation of MSCs

To induce adipogenic differentiation, the MSCs were seeded in a 12-well plate.When the MSCs were 90% confluent, the complete medium was replaced with an adipogenic medium (OriCellTMmouse MSCs Adipogenic Differentiation Media, Cyagen Biosciences, China). After 24 days, the cells were stained with Oil red O staining solution for 30 minutes and observed under a light microscope (AXIO, Oberkochen, Germany; Jin et al., 2021).

Flow cytometry analysis

Flow cytometry analysis (FACS) was used to detect surface markers on the MSCs (Soleimani and Nadri, 2009). The MSCs were incubated with the following antibodies (Table 1): CD29-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC),CD44-PE/Cy7, Sca-1-APC, CD11b-FITC, CD45-APC, CD31-FITC, CD117-APC,CD14-FITC, CD19-PE, Ly6G-PerCP, and CD4-FITC. A FACS flow cytometer C69(Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) was used for the analyses.

Acquisition of EVs-free FBS

FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was centrifuged at 100,000 ×gfor 6 hours. The resulting supernatant was used as EVs-free FBS.

Harvesting and identification of MSCs-EVs, and analysis of contents

A total EVs isolation kit (qEV, #1001622, iZonScience, Christchurch, New Zealand) was used to isolate and identify the EVs, as previously described (Xin et al., 2020). To summarize, when the MSCs density reached approximately 60%, the complete medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was replaced with the EVs-free FBS medium (DMEM/F-12 containing 10% EVs-free FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin) for 24 hours.The cell supernatant was then collected and centrifuged at 5752 ×gfor 30 minutes. The resulting supernatant was then filtered (0.22 μm, Millipore,Billerica, MA, USA) and transferred (about 15 mL) to a 100,000 MWCO ultrafiltration tube, and centrifuged again at 4000 ×gfor 30 minutes. The sample in each ultrafiltration tube was then concentrated to about 200-300 μL and transferred to a qEV column. The remaining steps were carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Finally, 3 mL of PBS suspension containing the EVs was used immediately or stored at -80°C. The EVs were quantified using a BCA protein assay kit (Cat# CW0014S, CWBIO, Haimen,Jiangsu, China).

A western blot analysis was used to detect the common markers of EVs,such as CD9 and tumour susceptibility gene 101 (TSG-101; Thery et al.,2018), and the morphology of the EVs was observed using a transmission electron microscope (TEM, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). The qNano platform (Izon Sciences Ltd., Christchurch, New Zealand) was used to determine the size and concentration of the EVs.

MSCs-EVs labeled with PKH67

To examine the distribution of EVs, the green fluorescent dye PKH67(MilliporeSigma) was used to mark the EVs. This was carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To summarize, PKH67 dye (4 μL) was mixed with Diluent C (1 mL) to obtain a PKH67 solution. This solution (1 mL) was then combined with the EVs solution (1 mL) in a centrifugation tube for 5 minutes;2 mL 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) was added to the centrifugation tube to stop the dyeing process. The mixture was then ultracentrifuged (100,000 ×g)for 70 minutes to obtain the EVs precipitate, and then washed in PBS (100,000×g) for 70 minutes. Finally, the PKH67-labeled EVs were resuspended in PBS.

Tracking the distribution and location of MSCs-EVs

To determine the distribution and localization of EVs in the BV-2 cells (a cell line of microglia; purchased from the Wuxi Puhe Biomedical Technology Co.,Ltd., Wuxi, Jiangsu, China), the cells were seeded on glass coverslips in 24-well plates and underwent OGD, followed by incubation with the PKH67-labeled EVs (10 μg/mL) for 24 hours. The glass coverslips were then collected, and the cells were fixed, blocked, and then stained with the primary antibody Iba-1 (a marker for microglia; 1:100) at 4°C for 16 hours. The next day, the glass coverslips were incubated with Alexa Fluor® 488 AffiniPure Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (H+L; 1:100) for 30 minutes at 37°C, followed by a 5-minute application of DAPI. Fluorescence images were captured using a fluorescence microscope(OLYMPUS-BX51, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Cell culture

BV-2 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM;Thermo Fisher Scientific), supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin,and 100 μg/mL streptomycin, in the CO2incubator (5% CO2) at 37°C.

OGD model and treatments

To induce OGD, BV-2 cells were incubated in a glucose-free medium(MACGENE, Shanghai, China) at 37°C within a hypoxic chamber (Sanyo Electric, Osaka, Japan; 1% O2, 5% CO2) for different durations of time (1, 3, and 5 hours). Afterwards, the cells were incubated in DMEM, supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and treated with EVs (10 μg/mL), EVs-miR-21aINC(10 μg/mL), or EVs-miR-21ainhibitor(10 μg/mL)for 24 hours in the CO2incubator (5% CO2) at 37°C (reoxygenation). Control BV-2 cells were cultured normally without OGD.

CCK8 assay

A Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay (Yiyuan Biotechnologies, Guangzhou,China) was conducted to assess cell viability. This involved adding 10 μL CCK-8 solution to each well (96-well plates), followed by incubation at 37°C for 3 hours in the CO2incubator (5% CO2). The cells were analyzed using a Microplate Reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 450 nm.

Cell transfection

MSCs were transfected with an miR-21a-5p inhibitor (miR-21ainhibitor; 60 nM) or its inhibitor negative control (INC; miR-21aINC; 60 nM), designed by GenePharma Corporation (Suzhou, China). This was carried out using a Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After 6 hours, the cells were cultured in the EVsfree FBS medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 24 hours; the EVs-miR-21aINCand EVs-miR-21ainhibitorwere then collected.

A total of 100 μg EVs, EVs-miR-21aINC, or EVs-miR-21ainhibitordissolved in 50 μL PBS was administered to the pups via an intracardiac injection, 24 hours after the HI (Xin et al., 2020).

RNase A and Triton X-100 treatment

To demonstrate the importance of the miR-21a-5p in the EVs, the RNA was degraded. For this, the EVs were incubated in the presence of 20 μg/mL RNase A (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and/or 0.5% Triton X-100 (Solarbio, Beijing, China)for 30 minutes at 37°C. The RNase digestion was stopped by adding 2 μL/mL RNase inhibitor (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and the RNA was isolated, as in a previous study (Xin et al., 2020).

Target prediction and Luciferase assay

The miR-21a-5p target genes in the BV-2 cells were determined using the target prediction databases TARGETSCAN-VERT (http://www.targetscan.org)and MIRDB (http://mirdb.org/miRDB/). The results showed that STAT3 is one of the target genes of miR-21a-5p. The plasmids pmirGLO-STAT3 WT-3′-UTR and pmirGLO-STAT3 MUT-3′-UTR were purchased from Gene Pharma (Suzhou,Jiangsu Province, China). BV-2 cells were transfected with the pmirGLOWT/Mut-STAT3, miR-21a-5p mimics, and miR-21a-5p NC (Gene Pharma),using Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer’s instructions(Thermo Fisher Scientific). A Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA) was used to detect firefly and renilla luciferase activity.

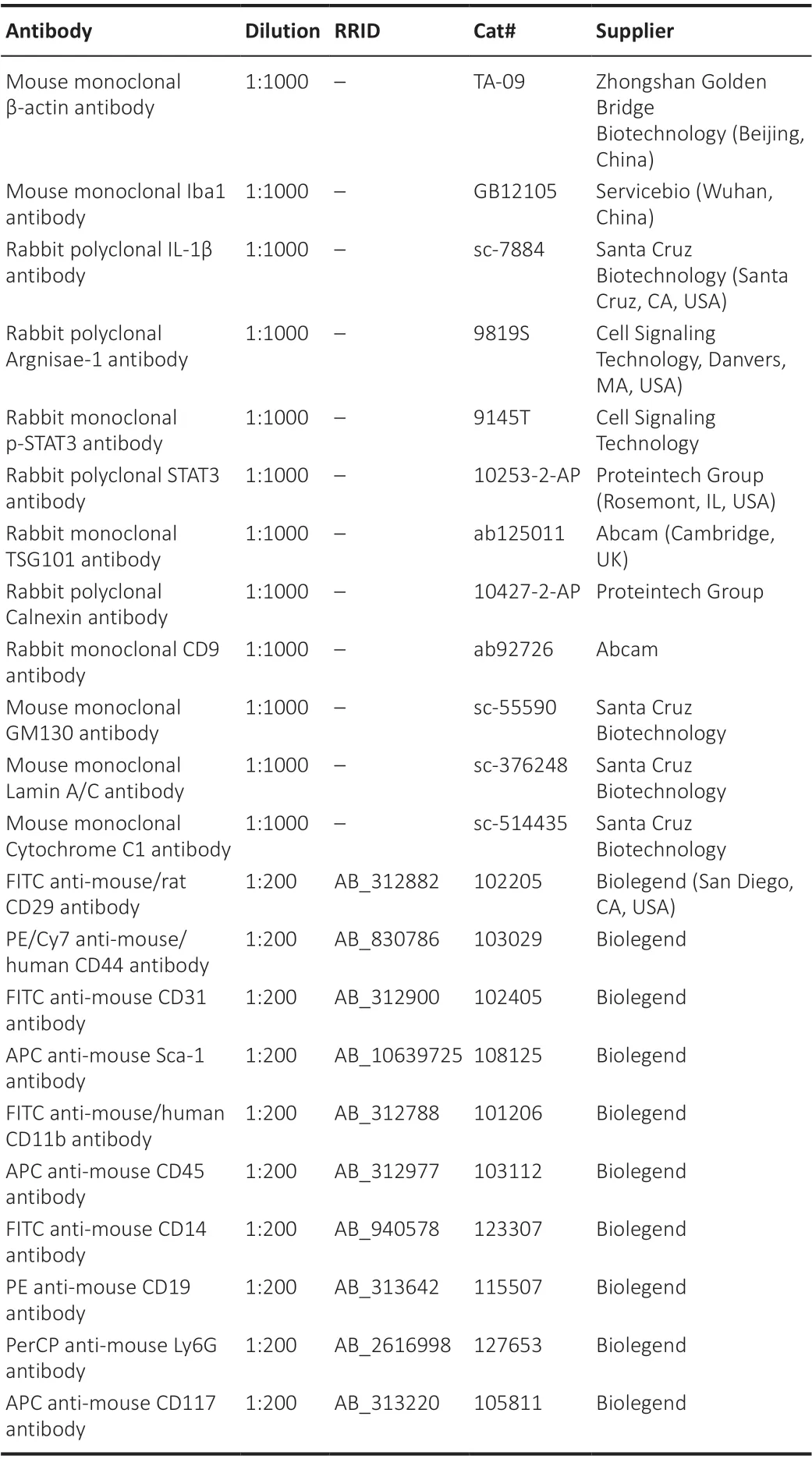

Table 1 |Primary antibodies used in the study

Table 2 |Secondary antibodies used in the study

RNA isolation and quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

The total RNA in the BV-2 cells and brain tissue was extracted using an Ultrapure RNA Kit (Cat# 01761/20114-1, CWBIO, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. MSCs-EVs were isolated using ExoQuick-TCTM(System Biosciences), and the RNA was extracted using a SeraMir EVs RNA Extraction Kit (System Biosciences, Mountain View, CA, USA). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using a Revert Aid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Cat# FSQ-101, TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan). The quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was performed using SYBR Green PCR master mix (Cat# PC3301, Aidlab Biotechnologies, Beijing, China)in a Bio-Rad IQ5 Real Time PCR System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) with gene-specific primer pairs (GenePharma, Shanghai, China). The RNA isolation and quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)was carried out as follows: 2 minutes at 95°C for denaturation, followed by 40 cycles of 15 seconds at 95°C and 30 seconds at 60°C. The expression level was standardized relative to the internal level (β-actin or U6), and the relative expression level was calculated using the 2-ΔΔCTmethod (Xin et al., 2020). The sequences used in the present study are shown in Table 3.

Table 3 |Primers used in polymerase chain reaction

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction analysis

RNA was extracted from the MSCs-EVs and cDNA was synthesized in reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) as described above. The cDNA for miR-21a-5p was then amplified using PCR with specific primers (Table 3). The PCR reaction products were separated using electrophoresis on 1.2%agarose/TAE gel (Biowest, Loire Valley, France) containing 0.1% GoldView (v/v),run at 90 V for 30 minutes. The resulting image was visualized with the Tanon Imaging System (Tanon-2500, Tanon Science & Technology Co., Shanghai,China).

Western blot analysis

MSCs-EVs, BV-2 cells, or the right cortex of the HI group were homogenized for 10 minutes in RIPA buffer (Cat# P0013B, Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology,Jiangsu, China) containing protease/phosphatase inhibitors and PMSF (Cat#ST506-2, Beyotime). The homogenate was then centrifuged at 13,800 ×gfor 10 minutes at 4°C. The proteins were separated using SDS-PAGE gels, run at 80 V for 30 minutes and at 120 V for 1 hour. They were then transferred to a PVDF membrane (Cat# IPVH00010, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) for at least 1 hour at 300 mA (note that the specific transfer time depends on the target molecular weight). The PVDF membrane was then blocked with 5% non-fat milk for 1 hour. The blots were probed with the following primary antibodies(Table 1) overnight at 4°C: rabbit polyclonal STAT3 (transcription factor)antibody, rabbit monoclonal p-STAT3 (phosphorylated transcription factor)antibody, rabbit polyclonal interleukin-1β (IL-1β; proinflammatory factor)antibody, rabbit polyclonal argnisae-1 (inflammatory factor) antibody, rabbit monoclonal TSG101 antibody (a marker for EVs), rabbit monoclonal CD9 antibody (a marker for EVs), rabbit polyclonal calnexin antibody (endoplasmic reticulum marker), mouse monoclonal GM130 antibody (mitochondrial marker), mouse monoclonal cytochrome C1 antibody (cytochrome C1),mouse monoclonal lamin A/C antibody (nuclear marker), and mouse monoclonal β-actin antibody (internal control). The next day, the membrane was incubated at room temperature for 1 hour with the secondary antibody(Table 2) HRP-labeled Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (H+L; 1:10,000) or HRP-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L; 1:10,000). The chemiluminescence was developed using a ECL kit (Cat# WBKLS0100, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and then detected using a Tanon Imaging System (Tanon-4600).

Statistical analysis

All of the animals and data were included in the analyses. The biochemical and histological analyses were conducted blind with respect to the experimental conditions, whereas this was not the case for thein vivomicroscopy and analyses. Statistical methods were not used to predetermine the sample sizes; however, the sample sizes in this study were similar to those in a previous report (Xin et al., 2020). The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 25 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). The different measures were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Comparisons between two groups were conducted using independent samplet-tests. When there were more groups, we carried out one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni correction for multiplepost hoccomparisons. APvalue < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

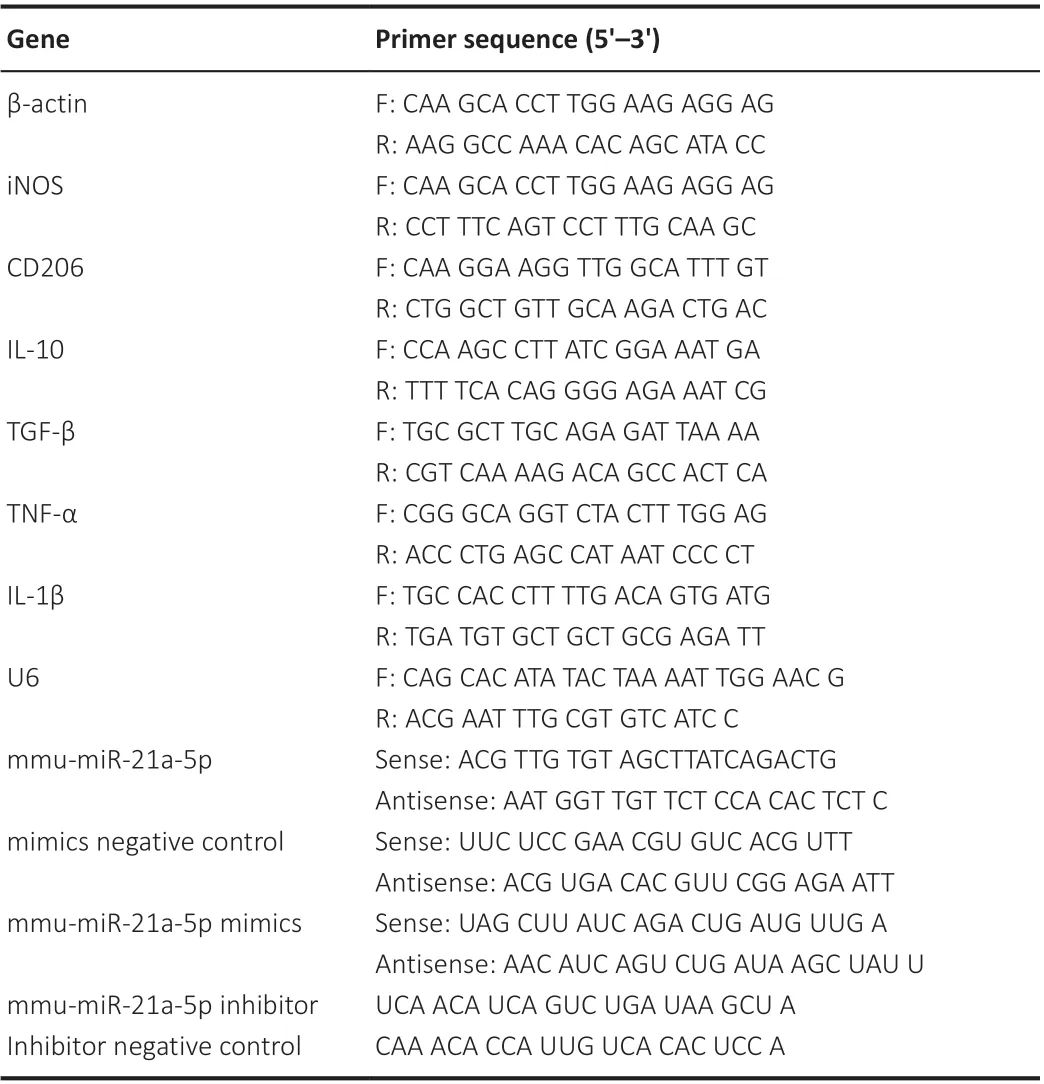

Characterization of MSCs and MSCs-EVs

Analysis of the TEM images revealed that the MSCs-EVs were around 100 nm in diameter with a rounded morphology (Figure 1A). Using qNano, the size of the MSCs-EVs was seen to range from 60 to 120 nm; they were thus identified as small vesicles (Figure 1B). The Western blot analyses revealed that the MSCs-EVs contained markers of EVs, specifically CD9 and TSG101; they did not contain calnexin, GM130, cytochrome C1, or lamin A/C (Figure 1C). Using PKH67-labeled EVs, it was found that they were internalized by BV-2 cells and could be seen in the cytoplasm (Figure 1D).

The MSCs were found to be spindle-shaped (Figure 1E) and capable of differentiating into osteoblasts and adipocytes (Figure 1F). FACS analyses showed that the MSCs were positive for CD44, CD29, and Sca-1, and negative for CD11b, CD45, CD31, CD117, Ly6G, CD19, CD14, and CD4 (Figure 1G). These results show that the extracted cells possessed the typical characteristics of MSCs and that they were able to differentiate.

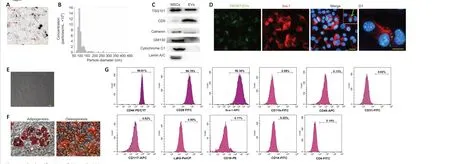

Treatment with MSCs-EVs inhibits OGD-induced microglial apoptosis

We first investigated whether MSCs-EVs were able to protect BV-2 cells against the effects of OGD. The results showed that OGD followed by 24-hour reoxygenation significantly decreased the viability of BV-2 cells. This was found for cells that had undergone OGD for 1 hour (t= 6.041,df= 10,P< 0.01), 3 hours (t= 8.095,df= 10,P< 0.001), and 5 hours (t= 10.364,df=10,P< 0.001; Figure 2A). The BV-2 cells that had undergone OGD for 3 hours and reoxygenation for 24 hours were selected for the subsequentin vitroexperiments. It was found that treatment with 10 or 20 μg/mL MSCs-EVs significantly increased the viability of the BV-2 cells (Figure 2B; 10 μg/mL:t=-4.426,df= 10,P< 0.01; 20 μg/mL:t= -9.253,df= 10,P< 0.001). However,this was not found for the treatment with 5 μg/mL MSCs-EVs (t= -1.591,df= 10,P> 0.05; Figure 2B). The furtherin vitroexperiments were performed using 10 μg/mL MSCs-EVs.

When the MSCs-EVs (10 μg/mL) were pretreated with RNase A, the protective effects of MSCs-EVs on cell viability were not significantly altered (P> 0.05).However, when the MSCs-EVs were pretreated with 0.5% Triton X-100 (a detergent that lyses membrane vesicles), there was a significant decrease in the protective effects (F(4,25)= 90.701,P< 0.001;post hoc P< 0.001). When the MSCs-EVs were pretreated with both Triton X-100 and RNase A, the protective properties significantly decreased (post hoc,P< 0.001), and the cell viability was found to be even lower than for the Triton X-100 pre-treatment alone (post hocP< 0.001; Figure 2C).

Treatment with MSCs-EVs promotes M2 polarization in BV-2 cells following OGD

As OGD induces the polarization of microglia to the pro-inflammatory M1 state, we examined the influence of EVs on BV-2 cells following OGD exposure. The qRT-PCR results showed that OGD exposure increased the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines post-OGD, including TNFα (t= -4.034,df= 10,P< 0.01 for 1-hour OGD;t= -2.360,df= 10,P< 0.05 for 3-hour OGD;t= -1.902,df= 10,P> 0.05 for 5-hour OGD), IL-1β (t= -3.124,df= 10,P< 0.05 for 1-hour OGD;t= -5.696,df= 10,P< 0.01 for 3-hour OGD;t= -4.932,df=10,P< 0.01 for 5-hour OGD), and iNOS (t= -0.393,df= 10,P> 0.05 for 1-hour OGD;t= -10.290,df= 10,P< 0.001 for 3-hour OGD;t= -4.490,df= 10,P<0.01 for 5-hour OGD; Figure 3A). In contrast, the OGD dramatically decreased the levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-10 (t= 3.000,df= 10,P< 0.05 for 1-hour OGD;t= 2.490,df= 10,P< 0.05 for 3-hour OGD;t= 2.847,df= 10,P< 0.05 for 5-hour OGD) and TGF-β (t= 5.071,df= 10,p< 0.001 for 1-hour OGD;t= 3.936,df= 10,P< 0.01 for 3-hour OGD;t= 5.737,df= 10,P< 0.001 for 5-hour OGD), as well as the M2 microglial surface marker CD206 (t= 5.134,df= 10,P< 0.001 for 1-hour OGD;t= 3.882,df= 10,P< 0.01 for 3-hour OGD;t= 3.317,df= 10,P< 0.01 for 5-hour OGD; Figure 3A).

The treatment with MSCs-EVs was found to significantly reduce the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (3-hour OGD condition), including tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα;F(2,15)= 157.208,P< 0.001;post hoc P< 0.001), IL-1β (F(2,15)=19.931,P< 0.001;post hoc P< 0.01), and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS;F(2,15)= 104.828,P< 0.001;post hoc P< 0.001; Figure 3B). In addition, the treatment significantly increased the levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines,including IL-10 (F(2,15)= 6.850,P< 0.01;post hocP< 0.05), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β;F(2,15)= 7.367,P< 0.01;post hoc P< 0.05), and CD206(F(2,15)= 17.170,P< 0.001;post hoc P< 0.001; Figure 3B). Taken together,these results indicate that treatment with MSCs-EVs regulates microglial polarization and promotes the M2, but not the M1, phenotype.

Figure 1 |Identification of EVs and MSCs.(A) Transmission electron microscopy image of EVs (red arrows). Scale bar: 200 nm. (B) Nanoparticle tracking analysis of MSCs-EVs using the qNano platform. (C) Western blot analysis of TSG101, CD9, GM130, Lamin A/C, Cytochrome C1, and Calnexin in the MSCs and EVs. (D) Immunofluorescence analysis showing the internalization of PKH67-EVs by the BV-2 cells (green arrow) that had undergone 3-hour OGD. Scale bar: 20 μm. (D1) Magnification of the boxed region in D showing the location of the PKH67 hotspots. Scale bar: 5 μm. (E)Fluorescence microscopy image of the MSCs showing a typical spindle-like morphology. Scale bar: 20 μm. (F) Images showing the MSCs’ capacity to differentiate into adipocytes and osteoblasts. Scale bars: 100 μm. (G) Flow cytometry analysis of MSCs surface markers (positive markers: CD44, CD29, and Sca-1; negative markers: CD11b, CD45, CD31, CD117, Ly6G,CD19, CD14, and CD4). EV: Extracellular vesicle; MSC: mesenchymal stromal cell; TSG101: tumour susceptibility gene 101.

Figure 2 |Effects of MSCs-EVs on OGD-induced microglial apoptosis.(A) The viability of BV-2 cells, measured using CCK8, for OGD durations of 1, 3, and 5 hours followed by 24-hour reoxygenation. n = 6 per group. (B) The viability of BV-2 cells in the presence or absence of MSCs-EVs. Cells had undergone 3-hour OGD followed by 24-hour reoxygenation. n = 6 per group. (C) The viability of BV-2 cells with no EVs , with EVs (10 μg/mL), with EVs (10 μg/mL) and RNase A (20 μg/mL), with EVs (10 μg/mL) and 0.5% TritonX-100, and with EVs (10 μg/mL), 0.5% Triton X-100, and RNase A (20 μg/mL). Cells had undergone 3-hour OGD followed by 24-hour reoxygenation. Cells incubated under standard cell culture conditions formed the “control” group and were used to define 100 % cell survival. Graphs show the mean ± SD. All of the experiments were carried out on six independent samples. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (independent samples t-test) in A and B; *** P <0.001 (one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni correction) in C. EV: Extracellular vesicle; MSC: mesenchymal stromal cell; OGD oxygen-glucose deprivation.

Figure 3 |EVs promote M2 polarization in BV-2 cells after OGD.(A) qRT-PCR analysis of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine mRNA expression in BV-2 cells after 1-, 3-, or 5-hour OGD followed by 24-hour reoxygenation. n = 6 per group. (B) qRTPCR analysis of the mRNA levels of IL-1β, iNOS, TNFα, IL-10, TGF-β, and CD206 in the presence or absence of MSCs-EVs. Cells had undergone 3-hour OGD followed by 24-hour reoxygenation. Cells incubated under standard cell culture conditions formed the “control” group. Graphs show the mean ± SD. All of the experiments were carried out on six separate samples. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (independent samples t-test) in A; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni correction) in B. EV: Extracellular vesicle; IL: interleukin; iNOS: inducible nitric oxide synthase; MSC: mesenchymal stromal cell; OGD oxygen-glucose deprivation; qRT-PCR: quantitative reverse transcription PCR; TGF-β: transforming growth factor-β; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor α.

miR-21a-5p in MSCs-EVs attenuates the inflammatory response following OGD in BV-2 cells

EVs-mediated miRNA transport has been proposed to be important for regulating target gene expression in cell-to-cell communication (Chevillet et al., 2014). We previously reported that miR-21a-5p is highly abundant in MSCs-EVs (Xin et al., 2020), and that it could account for the MSCs-EVs’immunomodulatory properties. In this study, to investigate the miR-21a-5p located in the lumen, the MSCs-EVs were treated with RNase A, Triton X-100, or RNase A + Triton X-100 (Ridder et al., 2015). The -RT-PCR analysis showed that the MSCs-EVs pretreated with RNase A or Triton X-100 alone still contained miR-21a-5p. Conversely, following pretreatment with both RNase A and Triton X-100, miR-21a-5p could no longer be detected in the MSCs-EVs (Figure 4A). These results confirm that miR-21a-5p is present inside the MSCs-EVs. Following OGD, the miR-21a-5p levels were found to be significantly lower. This was found for 1-hour OGD (t= 2.687,df= 10,P< 0.05),3-hour OGD (t= 2.969,df= 10,P< 0.05), and 5-hour OGD (t= 1.655,df=10,P> 0.05; Figure 4B). Treatment with MSCs-EVs was found to substantially increase the level of miR-21a-5p (OGD for 3 hours;F(2,15)= 20.783,P< 0.001;post hoc P< 0.001; Figure 4C).

To determine the role of miR-21a-5p in the neuroprotection conferred by MSCs-EVs, MSCs-EVs were pretreated with a miR-21a-5p inhibitor (EVs-miR-21ainhibitor) or its negative control (EVs-miR-21aINC). The qRT-PCR showed that the miR-21a-5p inhibitor substantially decreased the expression of miR-21a-5p in the MSCs-EVs (F(2,15)= 162.026,P< 0.001;post hoc P< 0.001; Figure 4D). The miR-21a-5p inhibitor was also found to reverse the increase in miR-21a-5p levels seen following MSCs-EVs treatment post-OGD (F(3,20)= 15.773,P< 0.001;post hoc P< 0.01; Figure 4E).

The cell viability was also assessed. It was found that the EVs-miR-21ainhibitorsignificantly reduced the BV-2 cell viability following OGD, compared with the EVs-miR-21aINC(F(3,20)= 31.199,P< 0.001;post hoc P< 0.001; Figure 4F).

The EVs-miR-21ainhibitorwas also found to suppress the anti-inflammatory effects of EVs-miR-21aINC, as shown by the mRNA levels of TNF-α (F(3,20)= 37.149,P< 0.001;post hoc P< 0.001), IL-1β (F(3,20) = 23.528,P< 0.001;post hoc P<0.001), iNOS (F(3,20)= 8.357,P< 0.01 ;post hoc P< 0.05), IL-10 (F(3,20)= 8.387,P< 0.01;post hoc P< 0.05), TGF-β (F(3,20)= 14.381,P< 0.001;post hoc P< 0.001),and CD206 (F(3,20)= 12.117,P< 0.001;posthoc P< 0.05; Figure 4G).

MiR-21a-5p in MSCs-EVs targets the STAT3 signaling pathway following OGD in BV-2 cells

We ran database searches to identify potential targets of miR-21a-5p that may be associated with microglial polarization and inflammation. We chose to focus on the miR-21a-5p/STAT3 pathway, as this has been shown to be critical for modulating the immune system and inflammation (Satriotomo et al.,2006; Fang and Zhang, 2020). We found that STAT3 phosphorylation (p-STAT3)increased following 1-hour OGD (t= -4.209,df= 6;P< 0.01), 3 h OGD (t=-3.198,df= 6;P< 0.05), and 5 h OGD (t= -4.348,df= 6;P< 0.01; Figure 5A).Treatment with MSCs-EVs significantly decreased the levels of p-STAT3 ([F(3,12)= 8.368,P< 0.001];post hoc p< 0.05; Figure 5B); however, this decrease was no longer apparent when a miR-21a-5p inhibitor was added to the MSCs-EVs(post hoc P< 0.05; Figure 5C).

A TargetScan analysis predicted that the miR-21a-5p would bind to the 3′-UTR of STAT3 (Figure 5D). We found that miR-21a-5p mimics decreased the luciferase activity associated with WT STAT3 3′ UTR, but not the luciferase activity associated with MUT STAT3 3′ UTR, in BV-2 cells (t= 25.649,df= 10;P< 0.001; Figure 5E).

MSCs-EVs inhibit microglial activation

Immunohistochemical staining showed that the Iba-1+cells in the sham group had a ramified shape. In the HI group, the microglia were activated and had a rounded, amoeboid-like appearance. The administration of MSCs-EVs significantly suppressed the microglial activation. The number of endpoints per Iba-1+cell was found to be significantly lower in the HI group compared with the sham group (F(2,9)= 14.672,P< 0.01;post hoc P< 0.01); it was also found that the length of the Iba-1+cell processes was shorter in the HI group than in the sham group (F(2,9)= 20.744,P< 0.001;post hoc P< 0.001). This difference was no longer apparent following treatment with MSCs-EVs (Figure 6).

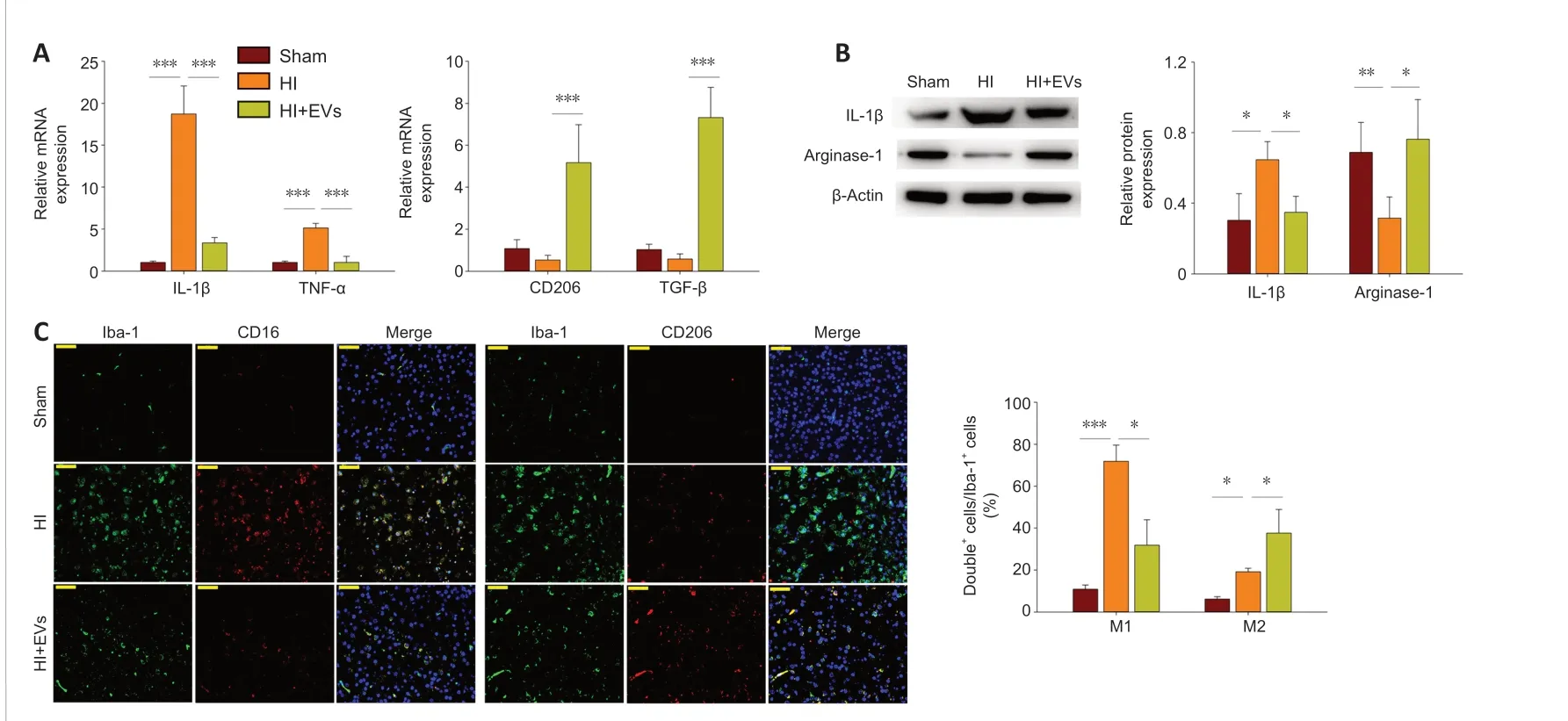

MSCs-EVs suppress HI-induced neuro-inflammation and promot M2 microglial polarization

Treatment with MSCs-EVs was found to attenuate the mRNA levels of proinflammatory cytokines 72 hours after HI, including IL-1β (F(2,15)= 143.562,P< 0.001;post hoc P< 0.001) and TNF-α (F(2,15)= 119.605,P< 0.001;post hoc P< 0.001; Figure 7A); the treatment also increased the mRNA levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines, including CD206 (F(2,15)= 32.918,P< 0.001;post hoc P< 0.001) and TGF-β (F(2,15)= 122.783,P< 0.001;post hoc P< 0.001; Figure 7A). Analysis of the protein levels revealed that the treatment significantly decreased the proteinl evels of IL-1β (F(2,9)= 9.967,P< 0.01;post hoc P< 0.05)and increased the protein levels of arginase-1 (F(2,9)= 7.362,P< 0.05;post hoc P< 0.05; Figure 7B).

Microglial polarization was assessed using immunofluorescence staining 3 days after the HI. It was found that the number of M1 phenotypes (Iba1+CD16+cells) in the right cortex was significantly lower in the HI + EVs group compared with the HI group (F(2,9)= 54.827,P< 0.001;post hoc P< 0.05;Figure 7C), whereas the number of M2 phenotypes (Iba1+CD206+cells) was significantly higher (F(2,9)= 21.274,P< 0.001;post hoc P< 0.05; Figure 7C).

Figure 4 |miR-21a-5p in MSCs-EVs attenuates the inflammatory response after OGD in BV-2 cells.(A) RT-PCR analysis of the levels of miR-21a-5p in EVs, EVs pretreated with RNase A, EVs pretreated with Triton X-100, EVs pretreated with Triton X-100 and RNase A, and RT-negative samples. (B) qRT-PCR analysis of the levels of miR-21a-5p in BV-2 cells after 1-, 3-, and 5-hour OGD followed by 24-hour reoxygenation. The control group was cultured normally without OGD. (C) qRT-PCR analysis of the levels of miR-21a-5p in the presence or absence of MSCs-EVs. The cells had undergone 3-hour OGD followed by 24-hour reoxygenation. (D)qRT-PCR analysis of the levels of miR-21a-5p in the different EVs (EVs, EVs-miR-21aINC, and EVs-miR-21ainhibitor). (E) qRT-PCR analysis of the levels of miR-21a-5p following treatment with EVs, EVs-miR-21ainhibitor, or EVs-miR-21aINC. The cells had undergone 3-hour OGD followed by 24-hour reoxygenation. (F) The viability of BV-2 cells, assessed using CCK8, following treatment with EVs, EVs-miR-21ainhibitor, or EVs-miR-21aINC. The cells had undergone 3-hour OGD followed by 24 -hour reoxygenation. (G) qRT-PCR analysis of the mRNA levels of TNF-α,IL-1β, iNOS, CD206, IL-10, and TGF-β for cells treated with no EVs, EVs, EVs-miR-21aINC, or EVs-miR-21ainhibitor. The cells had undergone 3-hour OGD followed by 24-hour reoxygenation.Graphs show the mean ± SD. The experiments were carried out on six separate samples. *P < 0.05 (independent samples t-test) in B; *P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001 (one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni correction) in C-G. EV: Extracellular vesicle; IL: interleukin; iNOS: inducible nitric oxide synthase; MSC: mesenchymal stromal cell; OGD oxygenglucose deprivation; qRT-PCR: quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction; RT-PCR: reverse transcription PCR; TGF-β: transforming growth factor-β; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor α.

Figure 5 |MiR-21a-5p in MSCs-EVs targets STAT3 signaling pathway after OGD in BV-2 cells.(A) Western blot analysis of phosphorylated STAT3 (p-STAT3) and STAT3 in BV-2 cells after 1-, 3-, and 5-hour OGD followed by 24-hour reoxygenation. The control cells were cultured normally without OGD. (B) Western blot analysis of the levels of p-STAT3 and STAT3 in the presence or absence of MSCs-EVs. The BV-2 cells had undergone 3-hour OGD followed by 24-hour reoxygenation. (C) Western blot analysis of the levels of p-STAT3 and STAT3 in BV-2 cells treated with EVs, EVs-miR-21ainhibitor, or EVs-miR-21aINC. The cells had undergone 3-hour OGD followed by 24-hour reoxygenation. (D) The sequence of mouse miR-21a-5p and its predicted binding site within the STAT3 3’ untranslated region (3′-UTR); the mutated sequence is also shown. (E) Luciferase activity in BV-2 cells transfected with luciferase plasmids containing WT STAT3 3′-UTR or MUT STAT3 3′-UTR and treated with miR-21a-5p mimics or miR-21a-5p NC. The cells were lysed to measure the relative luciferase activity. The experiments were carried out on four independent samples. Graphs show the mean ± SD; *P <0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (independent samples t-test) in A and E; *P < 0.05 (one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni correction) in B and C. EV: Extracellular vesicle; MSC:mesenchymal stromal cell; OGD oxygen-glucose deprivation.

MiR-21a-5p in MSCs-EVs mediates the neuroprotective effects through the STAT3 signaling pathway

To show that the MSCs-EVs’ anti-inflammatory effects are mediated by miR-21a-5p, mice were injected with either PBS, MSCs-EVs, EVs-miR-21ainhibitor,or EVs-miR-21aINC. As previously found (Chu et al., 2020; Xin et al., 2020), the MSCs-EVs significantly decreased the brain water content (F(2,9)= 50.806,P<0.001;post hoc P< 0.001) and infarct volumes (F(2,9)= 189.879,P< 0.001;post hoc P< 0.001) in the HI neonatal mice (Additional Figure 1). In contrast, this was not found for the EVs-miR-21ainhibitor(Additional Figure 2).

As in a previous study (Satriotomo et al., 2006), p-STAT3 staining was found to be localized in the Iba1+microglia/macrophages in the hemisphere ipsilateral to the injury (Additional Figure 3). In line with ourin vitroresults, the EVs treatment significantly reduced p-STAT3 (F(2,9)= 17.488,P< 0.01;post hoc P< 0.01) in the right cortex 3 days following the HI (Figure 8A). This effect was significantly smaller with the EVs-miR-21ainhibitor(F(3,12)= 32.603,P< 0.001;post hoc P< 0.01; Figure 8B).

The qRT-PCR showed that the treatment with EVs-miR-21ainhibitorupregulated the mRNA levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β (F(3,20)=10.615,P< 0.001;post hoc P< 0.01) and TNFα (F(3,20)= 14.258,P< 0.001;post hoc P< 0.001), while the mRNA levels were downregulated for CD206 (F(3,20)= 68.897,P< 0.001;post hoc P< 0.001) and TGF-β (F(3,20)= 23.655,P< 0.001;post hoc P< 0.001; Figure 8C). It was also found that the EVs-miR-21ainhibitortreatment increased the protein level of IL-1β (F(3,12)= 9.264,P< 0.01;post hoc P< 0.05) and reduced the protein level of Arginase-1 (F(3,12)= 33.357,P<0.001;post hoc P< 0.001) compared with the EVs-miR-21aINCtreatment group(Figure 8D).

Figure 6 |MSCs-EVs decrease microglial activation in the cortex ipsilateral to the HI.Upper panels: Immunohistochemistry images of microglia with Iba-1 staining in the sham, HI, and HI + EVs groups. Green arrowheads show the resting microglia (ramified microglia)and red arrowheads show the activated microglia (amoeboid shape). Scale bar: 25 μm. Lower panels: Quantification of the number of endpoints per Iba-1+ cell and the length of the cell processes in the infarct core. All of the experiments were carried out on four independent samples. Graphs show the mean ± SD; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni correction). EV: Extracellular vesicle; HI: hypoxia-ischemia; MSC: mesenchymal stromal cell.

Figure 7 |MSCs-EVs promote M2 microglial polarization and suppress HI-induced neuroinflammation in the cortex ipsilateral to the HI.(A) Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction analysis of the mRNA levels of IL-1β, TNFα, TGF-β, and CD206 in the presence or absence of MSCs-EVs, 72 hours post-HI. (B) Western blot analysis of the levels of IL-1β and Arginase-1 in the presence or absence of MSCs-EVs, 72 hours post-HI. Results are shown for the cortex ipsilateral to the HI. (C)Representative photographs showing immunofluorescence staining of Iba-1 (green), CD16 (red), and CD206 (red) in the cortex ipsilateral to the HI, 72 hours post-HI. Scale bars: 50 μm.Graphs show the mean ± SD; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni correction). All of the experiments were carried out on six (A) or four(B, C) independent samples. Double+ cells mean Iba-1+CD16+ cells or Iba-1+CD206+ cells. EV: Extracellular vesicle; HI: hypoxia-ischemia; IL: interleukin; MSC: mesenchymal stromal cell;TGF-β: transforming growth factor-β; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor α.

Figure 8 | MiR-21a-5p in MSCs-EVs provides neuroprotection through STAT3 signaling pathway in the cortex ipsilateral to the HI.(A) Western blot analysis of the levels of p-STAT3 and STAT3 in the presence or absence of MSCs-EVs, 72 hours post-HI. Results are shown for the cortex ipsilateral to the HI. (B)Western blot analysis of the levels of p-STAT3 and STAT3 in the presence or absence of EVs, EVs-miR-21ainhibitor, or EVs-miR-21aINC. Results are shown for the cortex ipsilateral to the HI. (C)Quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction analysis of the mRNA levels of IL-1β, TNF-α, TGF-β, and CD206 in the presence or absence of EVs, EVs-miR-21ainhibitor, or EVs-miR-21aINC. (D) Western blot analysis of the levels of IL-1β and Arginase-1 in the presence or absence of EVs, EVs-miR-21ainhibitor, or EVs-miR-21aINC. Results are shown for the cortex ipsilateral to the HI. Graphs show the mean ± SD; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni correction). All of the experiments were carried out on four (A, B, D) or six (C) independent samples. EV: Extracellular vesicle; HI: hypoxia-ischemia; IL: interleukin; MSC: mesenchymal stromal cell; p-STAT3: phosphorylated STAT3;STAT3: signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; TGF-β: transforming growth factor-β; TNF-α: tumour necrosis factor α.

Discussion

MSCs-EVs have recently been recognized for their potential to treat inflammatory diseases and tissue injury (Iavorovschi and Wang, 2020).In this study, we found that MSCs-EVs alleviated the neuroinflammation following HI, and that this was associated with the polarization of microglia from a pro-inflammatory to an anti-inflammatory state, as seen bothin vivoandin vitro. We obtained evidence that miR-21a-5p in the MSCs-EVs may target STAT3 to change the microglial polarization, which would then regulate neuroinflammation and maintain brain homeostasis. STAT3 may thus represent a new potential therapeutic target for the treatment of HI.

MSCs-EVs suppress neuroinflammation by changing microglia from a pro-inflammatory to an anti-inflammatory state

The therapeutic effects of MSCs-EVs relate to their immunosuppressive properties. In a previous study, microvesicles from MSCs were found to reduce LPS-induced inflammatory responses in BV-2 cells (Jaimes et al.,2017). Another study used an animal model of Alzheimer’s disease and found that MSCs-EVs suppressed the activation of microglia, polarized the microglia towards an anti-inflammatory phenotype, and increased the dendritic spine density of neurons (Losurdo et al., 2020). MSCs-EVs have also been found to suppress early inflammatory responses following a traumatic brain injury in rats by modulating the microglia/macrophage polarization (Ni et al., 2019).Following HI brain injury in newborn rats, umbilical cord MSCs-EVs have been shown to be internalized by microglia and act to reduce the neuroinflammation(Thomi et al., 2019). Treatment with MSCs-EVs has also been found to significantly reduce microgliosis and prevent reactive astrogliosis following LPS-stimulated brain injury (Drommelschmidt et al., 2017).

In our previous work, we found that MSCs-EVs administered by intracardiac injection following HI were localized in the microglia (Chu et al., 2020; Xin et al., 2020). The treatment was found to reduce neuroinflammation by suppressing the expression of osteopontin in the microglia/macrophages(Xin et al., 2021). In the present study, we found that the MSCs-EVs were internalized by BV-2 cells following OGD, and resulted in a decrease in BV-2 cell apoptosis, a reduction in the expression of M1 microglial markers(including IL-1β, iNOS, and TNF-α), and an increase in the expression of M2 microglial markers (including CD206, TGF-β, and IL-10). These results were confirmed in ourin vivostudy, where MSCs-EVs treatment was found to significantly decrease the mRNA levels of IL-1β and TNF-α, and increase the mRNA levels of CD206 and TGF-β. In addition, the EVs treatment was found to decrease the protein levels of IL-1β and increase the protein levels of arginase-1. The number of microglia with the M1 phenotype (Iba1+CD16+cells) was also found to be lower following the MSCs-EVs treatment, while the number of M2 phenotypes (Iba1+CD206+cells) was found to be higher in the cortex ipsilateral to the ligation. These results indicate that MSCs-EVs modulate the microglial polarization and could potentially be used as a therapeutic treatment for HI brain damage.

Anti-inflammatory mechanisms involving the miR-21a-5p in MSCs-EVs

One of the main mechanisms underlying the therapeutic effects of MSCs-EVs relates to the transfer of miRNA between cells. We previously reported that miR-21a-5p is highly abundant in MSCs-EVs (Xin et al., 2020), and several studies have shown that miR-21 plays an important role in the anti-inflammatory response in many diseases, such as tumors, infections,and other diseases that are associated with inflammation (Sheedy et al.,2010; Sheedy, 2015). It has been found that the overexpression of miR-21 substantially inhibits the production inflammatory cytokines and can also improve cardiac function following myocardial infarction (Yang et al., 2018).In an animal model of Alzheimer’s disease, EVs from hypoxia-preconditioned MSCs were found to improve learning and memory; this was attributed to improvements in synaptic function and the regulation of inflammatory responses via miR-21 (Cui et al., 2018). In another study, the overexpression of miR-21 in EVs was found to reduce cell apoptosis and improve cardiac function following myocardial infarction (Song et al., 2019).

The present study showed that treatment with MSCs-EVs markedly increased the expression of miR-21a-5p in BV-2 cells following OGD. The beneficial effects of MSCs-EVs on microglial polarization, inflammatory cytokines,and cell survival were no longer apparent when a miR-21a-5p inhibitor was added. Similar results were obtained in ourin vivostudy: a EVs-miR-21ainhibitorcounteracted the beneficial effects of MSCs-EVs on microglial polarization and inflammatory cytokines following HI. Taken together, it can be seen that the miR-21a-5p in MSCs-EVs plays an important role in neuroprotection following HI, bothin vitroandin vivo.

STAT3 signaling pathway contributes to MSCs-EVs’ effect on microglial M2 polarization

The STAT3 signaling pathway is important for cellular growth, differentiation,and survival (Yu et al., 2009), and it is involved in various inflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses (Rawlings et al., 2004). Previous studies have shown that activated STAT3 is predominantly localized in the macrophages/microglia following cerebral ischemia (Satriotomo et al., 2006), and that it induces the expression of pro-inflammatory factors (Satriotomo et al.,2006; Li et al., 2018). In the present study, STAT3 was found to be activated following HI, bothin vivoandin vitro, which is in line with the increase in proinflammatory cytokines and the decrease in anti-inflammatory cytokines. The MSCs-EVs treatment was found to suppress the STAT3 activation, which is consistent with the polarization of microglia from a pro-inflammatory to an anti-inflammatory state following HI. We were able to show that miR-21a-5p binds directly to the STAT3 gene, using a Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay, and we found that an increase in miR-21a-5p levels in microglia was associated with a decrease in activated STAT3. A miR-21a-5p inhibitor was found to counteract this effect, bothin vivoandin vitro. Taken together, these results suggest that MSCs-EVs regulate microglial activation by transferring miR-21a-5p to the microglia and targeting the STAT3 pathway.

Limitations

Our study has some limitations. Firstly, we only examined the effects of the EVs’ miR-21a-5p on short-term HI outcomes. It remains to be determined whether long-term effects can be identified. Secondly, we did not consider whether the EVs’ miR-21a-5p affects the peripheral immune cells, and whether these may participate in the regulation of neuroinflammation.Thirdly, we did not examine whether the same therapeutic effect can be achieved using a STAT3 inhibitor (such as STAT3 siRNA); if this were found to be the case, the cost of treatment would be reduced. Further research is needed to examine these three points.

Conclusion

The study showed that treatment with MSCs-EVs attenuated HI brain injury in neonatal mice. This was due to the transfer of miR-21a-5p, which induced the polarization of microglia to the M2 phenotype by targeting STAT3.

Acknowledgments:We thank the Animal Medicine Center of Shandong University for providing experimental animals and the Basic Medical Sciences of Shandong University for providing experimental places and instrument.

Author contributions:ZW made substantial contributions to study design,data interpretation, writing and revising of the manuscript, and final revision of the manuscript. DXL conceived experiments, analyzed the data and final revision of the manuscript. DQX made substantial contributions to laboratory work, analyzed the data, and edited the manuscript. YJZ performed Western blotting; TTL, HFK, and CCG performed cell culture. XFG and WQC revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest:The authors have no financial or personal conflict of interest to disclose.

Author statement:This paper has been posted as a preprint on Research Square with doi: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-313905/v1, which is available from: https://assets.researchsquare.com/files/rs-313905/v1/776e6119-c7dc-45df-8475-4cfaa3c6b65c.pdf?c=1631879647.

Availability of data and materials:All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Open access statement:This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons AttributionNonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

Open peer reviewer:Gokul Krishna, The University of Arizona College of Medicine-Phoenix, USA.

Additional files:

Additional Figure 1:MSCs-EVs suppresses HI-induced edema and infarct in mice at 3 days post-HI insult.

Additional Figure 2:MiR-21a-5p regulates neuroprotection effects of MSCs-EVsfollowingHI.

AdditionalFigure 3:p-STAT3 is localized in the Iba1+cells microglia/macrophages in the ipsilateral hemisphere of mice.

- 中国神经再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- Complement activation kindles the transition of acute posttraumatic brain injury to a chronic inflammatory disease

- Role of adipose tissue grafting and adipose-derived stem cells in peripheral nerve surgery

- Potential significance of CX3CR1 dynamics in stress resilience against neuronal disorders

- Toxicities of amyloid-beta and tau protein are reciprocally enhanced in the Drosophila model

- A comparative analysis of differentially expressed genes in rostral and caudal regions after spinal cord injury in rats

- Basic mechanisms of peripheral nerve injury and treatment via electrical stimulation