Febrile infants: written guidelines to reduce non-essential hospitalizations

Ji Yoon Oh ·Soo-Young Lee

Management of febrile infants, especially those younger than 3 months of age, is of clinical importance due to the relatively high risk of serious bacterial infection (SBI), such as bacterial meningitis, bacteremia, or urinary tract infection (UTI) [1].Fortunately, reliable guidelines for assessing the risk of SBI in febrile infants have been developed to help determine whether an infant should be hospitalized,undergo lumbar puncture, or be treated with antibiotics [2].However, many hospitals do not have written institutional guidelines, so clinicians often make decisions based on their own experience and knowledge [3– 5].For a consistent approach to febrile infants, our hospital plans to introduce written guidelines.In this study, we estimated the expected effects of these guidelines and compared our data with the results of previous domestic studies.

Our study retrospectively reviewed the medical records of febrile infants aged 29–90 days who visited the emergency department at a university hospital in Bucheon, Republic of Korea, between January 2017 and December 2019.Of these patients, 62.9% (843/1,340) were hospitalized.After excluding patients with missing records, 722 final patients were enrolled in this study.

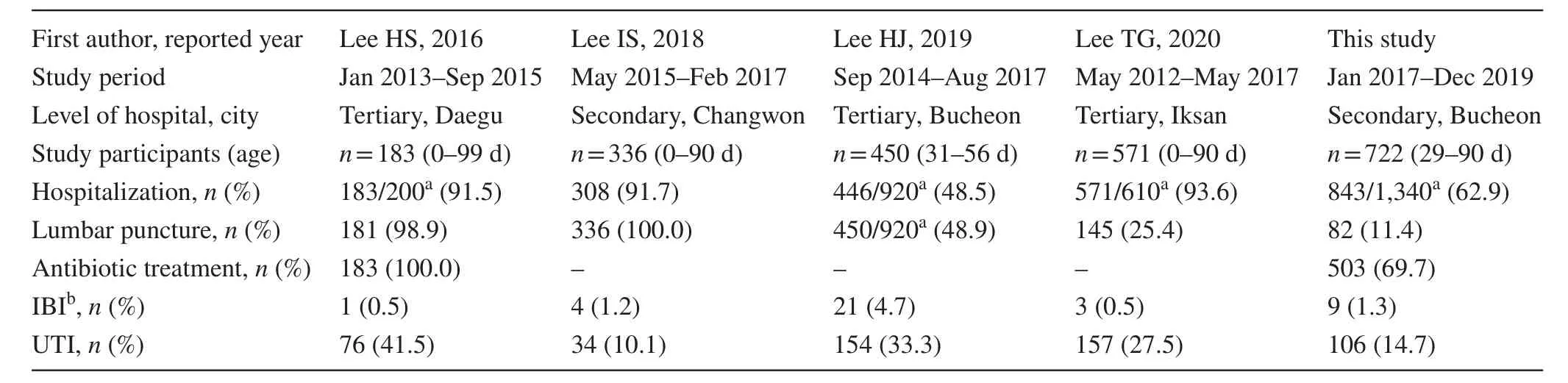

Of the 722 enrolled inpatients, 116 (16.1%) were diagnosed with SBI, including UTI (106 cases), bacteremia ( five cases), bacterial meningitis (four cases), and osteomyelitis(one case).All patients had blood tests, urinalysis, and chest radiography.In addition, 424 (59.0%) were tested for respiratory virus polymerase chain reaction, and 227 (31.4%) were tested for stool rotavirus.Lumbar puncture was performed in 82 (11.4%), and 503 (69.7%) received antibiotic treatment during hospitalization.The guidelines applied in this study were based on the Rochester criteria and were modified for study hospital use [1].Febrile infants were defined as lowrisk patients suitable for outpatient management if all of the following five criteria were met: (i) age > 28 days, (ii)well appearing, (iii) white blood cell (WBC) 5000–15,000/mm 3 and C-reactive protein ≤ 20 mg/L, (iv) urine WBC ≤ 10/high power field, and (v) chest radiograph without in filtrate.Among 722 inpatients, 83 (11.5%) appeared ill, 209 (28.9%)had abnormal blood test results, 148 (20.5%) demonstrated pyuria, and 21 (2.9%) had in filtrates on chest radiograph.When the guidelines were applied to inpatients, 404 (56.0%)met all five criteria and were classified as low-risk patients.Of the 404 low-risk patients, only 4 (1.0%) had SBI, but 224 (55.4%) received antibiotic treatment.Table 1 compares our results with those of previous Korean studies on febrile infants.Regardless of the prevalence of invasive bacterial infection or UTI, rates of hospitalization, lumbar puncture,or antibiotic treatment varied among the surveyed hospitals.

Table 1 A comparison of the present study with previous Korean studies on febrile infants [2, 6– 8]

Most guidelines for assessing the risk of SBI in febrile infants suggest that low-risk patients can be managed in an outpatient clinic without antibiotic treatment, while highrisk patients should be hospitalized and receive empiric antibiotics [1, 3].However, in this study, low-risk patients accounted for more than half (404/722) of all hospitalizations, and more than half (224/404) of these patients received antibiotic treatment during hospitalization.Overmanagement of febrile infants occurred because there were no written guidelines available during the study period[3– 5].In this study, we found an inconsistent approach to febrile infants in domestic hospitals.This finding reflects the lack of written guidelines in many hospitals [4].For proper management of febrile infants, it is important to develop guidelines with high sensitivity and specificity, but it is also necessary to introduce written guidelines that are universal and easily applicable [2, 6].

In summary, more than half of the inpatients in this study were low-risk patients who could have been managed in an outpatient clinic.The introduction of written guidelines to assess the risk of SBI in febrile infants can reduce non-essential hospitalizations and avoid lumbar puncture and antibiotic treatment during hospitalization.

Author contributionsOJY contributed to data curation, investigation, visualization, writing of original draft, review and editing; LSY contributed to conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, methodology, supervision, validation, review and editing.Both the authors approved the final version of the manuscript to be published.

FundingThis work was supported by the Institute of Clinical Medicine Research of Bucheon St.Mary’s Hospital, Research Fund, 2020.

Data availabilityThe datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethical approvalThis study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Bucheon St.Mary’s Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea (HC20RASI0064).

Conflict of interestNone of the authors participated in the journal’s review of, or decisions related to this manuscript.Nofinancial or nonfinancial benefits have been received or will be received from any party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Informed consentInformed consent was waived for this study due to its retrospective nature.

World Journal of Pediatrics2021年5期

World Journal of Pediatrics2021年5期

- World Journal of Pediatrics的其它文章

- Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis as a manifestation of Kawasaki disease

- Rising serum potassium and creatinine concentrations after prescribing renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system blockade:how much should we worry?

- Role of ultrasound in the diagnosis of cervical tuberculous lymphadenitis in children

- Nasogastric or nasojejunal feeding in pediatric acute pancreatitis:a randomized controlled trial

- Pediatric upper extremity firearm injuries: an analysis of demographic factors and recurring mechanisms of injury

- Serum vitamin E concentration is negatively associated with body mass index change in girls not boys during adolescence