Rising serum potassium and creatinine concentrations after prescribing renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system blockade:how much should we worry?

Farahnak Assadi

Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) blockade is often the first-line medication for treating pediatric and adult patients with hypertension, especially those with preexisting chronic kidney disease (CKD) [1, 2].However,the rise in serum creatinine and potassium concentrations following RAAS blocked may pose therapeutic challenges whether it is safe to treat hypertensive patients with CKD,by inhibiting [3].Thus, many clinicians neglect to use angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) or angiotensin receptor blockade (ARB) especially in patients with CKD because of fear in either reduction of glomerular filtration rate (GFR) or elevation in serum creatinine and potassium concentrations.

Clinical studies demonstrate a strong association between acute rises in serum creatinine and potassium concentrations up to 30% above the baseline within the first 2 months following RAAS inhibition [1– 3].This is driven by the magnitude of blood pressure reduction as much as it is by RAAS inhibition itself [2].The initial rise in serum potassium and creatinine concentrations following therapy with RAAS blockade is reversible [4– 13].The mechanisms responsible for the initial acute rise in serum creatinine and potassium concentrations following RAAS inhibition are reduced effective arterial blood volume and glomerular hypoperfusion[14].

In patients with preexisting CKD, single-nephron GFR functions at a relatively higher baseline pressure to compensate for the fewer functioning nephron [14].Under these conditions, the inhibition of the RAAS by either ACEI or ARB leads to a greater reduction in intraglomerular pressure in these remnant nephrons [15].Moreover, hypoperfusion secondary to lowering blood pressure effect from ACEI or ARB further lowers the already reduced intraglomerular pressure imposed by ACEI or ARB and lead to greater reduction in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and elevation of serum creatinine concentration [4, 6].

Previous trials demonstrate that a rise in serum creatinine of 30% or less above baseline, within the first 2 months of therapy with RAAS inhibition in patients with CKD who achieve their blood pressure goal should not be a cause for concern [7– 9].Further, the limited initial rise in serum creatinine level following RAAS inhibition is reversible and stabilizes within 2 months following therapy with RAAS initiation [2, 16].Thus, stopping ACEI or ARB based on these findings would be a mistake because long-term follow-up studies extending over 6 years show clear benefits in terms of protection against the progression of renal disease[10– 12].Withdrawal of ACEI or ARB should be considered only when the rise in serum creatinine is greater than 30% above baseline value or the GFR falls below 30 mL/min/1.73 m 2 within the first 2 months following RAAS inhibition therapy, which is seen in patients with advanced CKD has the potential to lead to increased morbidity and mortality [2].

Existing data from large clinical trials demonstrate that patients with the lowest degree of renal insufficiency benefit the greatest protection against progression of renal disease with ACEI initiation [4, 14, 15].CKD patients with baseline serum creatinine < 1.4 mg/dL show little decline in GFR value (5–20%), whereas those with relatively greater degrees of renal dysfunction have greater fall in GFR following RAS inhibition [14, 15].It is noteworthy to mention that the renal protective effect of ACEI or ARB is limited to CKD patients with the serum creatinine up to 3.0 mg/dL or less (GFR > 30 mL/1.73 m2) [3, 6, 7, 13].

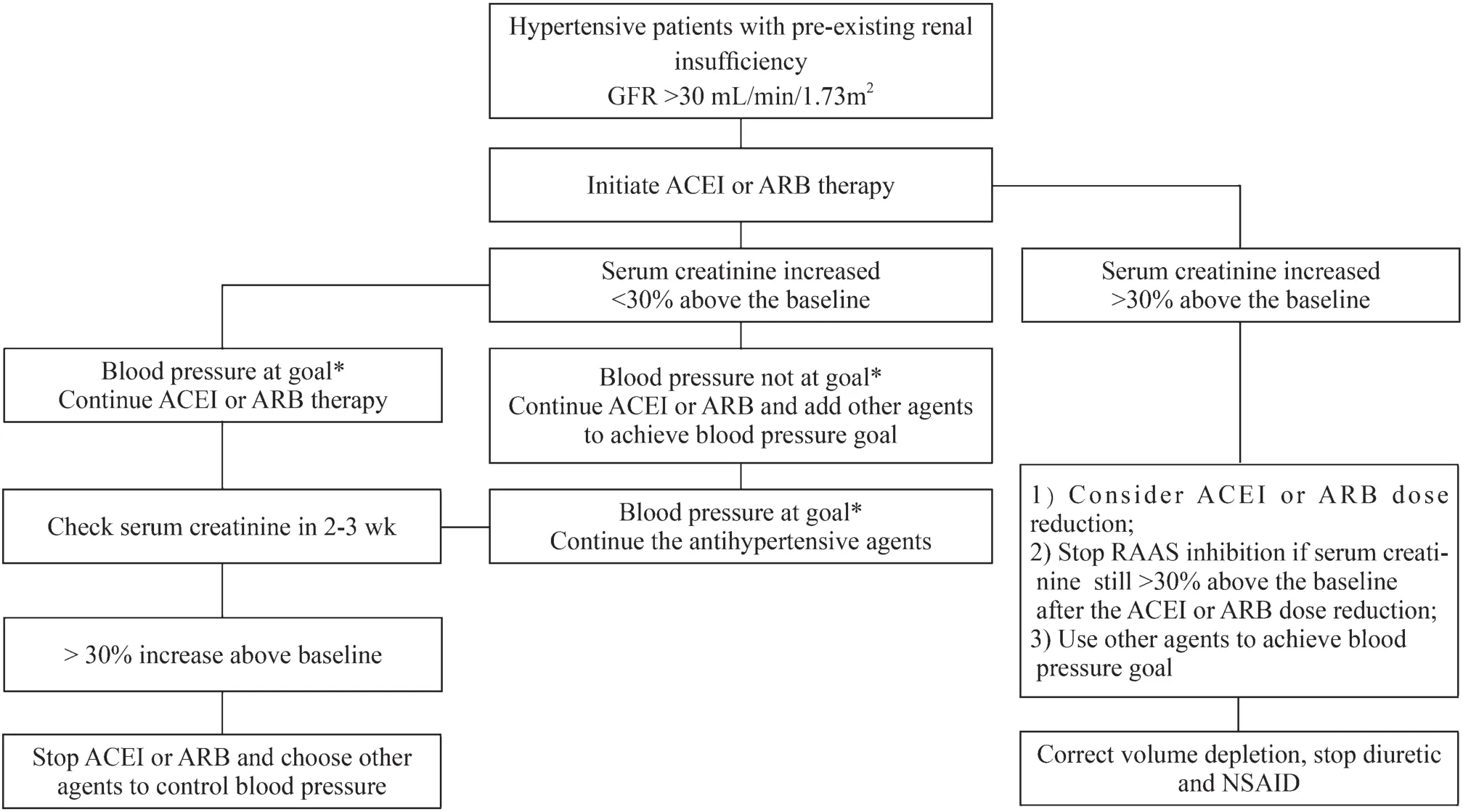

Figure 1 provides a simplified algorithm illustrating how to approach a rising serum creatinine level or a fall in GFR after the start of an ACEI or ARB therapy in patients with preexisting renal insufficiency.

Fig.1 Simplified algorithm illustrating impact of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) or angiotensin receptor blocker(ARB) therapy in patients with renal insufficiency.GFR glomerular filtration rate, NSAID nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, * Blood pressure < 135/85 mmHg for adolescents and adult patients and less than 50th–75th percentile for children aged less than 13 years with renal insufficiency with or without diabetes mellitus

Author contributionsFA conceptualized and designed the study, writing of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

FundingNo funding was secured for this study.

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethical approvalThe study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by hospital ethic’s committee.

Conflict of interestThe author has no conflicts of interest relevant to this study to disclose.

World Journal of Pediatrics2021年5期

World Journal of Pediatrics2021年5期

- World Journal of Pediatrics的其它文章

- Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis as a manifestation of Kawasaki disease

- Febrile infants: written guidelines to reduce non-essential hospitalizations

- Role of ultrasound in the diagnosis of cervical tuberculous lymphadenitis in children

- Nasogastric or nasojejunal feeding in pediatric acute pancreatitis:a randomized controlled trial

- Pediatric upper extremity firearm injuries: an analysis of demographic factors and recurring mechanisms of injury

- Serum vitamin E concentration is negatively associated with body mass index change in girls not boys during adolescence