Pediatric upper extremity firearm injuries: an analysis of demographic factors and recurring mechanisms of injury

D.Spencer Nichols ·Mitsy Audate ·Caroline King ·David Kerekes ·Harvey Chim ·Ellen Satteson

Abstract

Background Little is known regarding risk factors specific to pediatric upper extremity firearm injuries.The purpose of this study is to evaluate pediatric patients treated for these injuries to identify at-risk populations and recurring mechanisms of injury.

Methods A 20-year retrospective review was conducted.Patients 17 years of age and younger, with upper extremity injuries related to a firearm, were included.Analysis involved Fisher’s exact and Chi-square tests.

Results One hundred and eighty patients were included.The mean age was 12.04 ± 4.3 years.Most included patients were male (85%).Interestingly, females were more frequently victims of assault ( P = 0.03), and males were more frequently injured due to accidental discharge ( P < 0.001).The most affected race/ethnicity was White-not Hispanic or Latino (48%).The hand was the most frequent location injured (31%) and was more likely to be accidental than proximal injuries ( P = 0.003).Air rifles were the most common firearm type used (56%).Pistols were implicated in 47 (26%) cases, rifles in 17 (9%), and shotguns in 10 (6%).Ninety-nine (55%) patients had procedures in the operating room.The most frequent procedure was foreign body removal (55%).

Conclusions Risk factors such as male sex, White-not Hispanic or Latino race/ethnicity, and adolescent age were attributed to increased risk for injury.Male sex was associated with increased risk of injury by accidental discharge and female sex with intentional assault.Air rifles were the most common firearm type overall, although female sex was associated with increased risk for injury by powder weapon.

Keywords Firearm ·Injury ·Pediatric ·Trauma ·Upper extremity

Introduction

Of all high-impact traumatic events known to cause significant morbidity and mortality in pediatric populations,firearm injuries are especially dangerous [1, 2].In 2016,firearm-related injuries were the second leading cause of mortality among children and adolescents aged 1–19 years,accounting for 15% of pediatric deaths [3, 4].More recently,in 2018, a study conducted by Bayouth et al.determined that the incidence and mortality of pediatric firearm injuries were largely unchanged despite increased firearm safety and counseling programs.In a 2019 study by Cunningham et al.firearm-related injuries remained the second leading cause of death among pediatric populations [5, 6].Aside from fatalities, firearm injuries also remain a source of signifi-cant financial burden for pediatric patients, their families,and global healthcare systems [5].In 2014, firearms were responsible for 12,000 pediatric emergency room visits and 7400 hospitalizations, and from 2006–2010, costs from firearm-related pediatric emergency room visits totaled $88 billion in the United States alone [7, 8].

Unique characteristics of pediatric individuals that put them at risk for serious firearm injury include incomplete skeletal development, reduced subcutaneous and visceral fat,and insufficient bony protection of packed visceral organs[2].Compared to adults, the increased body-surface-area-tobody-mass ratio also makes this population more susceptible to fluid loss and hemodynamic instability following trauma[1, 3].Known risk factors for firearm injury, hospitalization,and death in pediatric patients include male sex, adolescent age, racial minority status, and residence in neighborhoods of significant socioeconomic disadvantage [5, 9, 10].While these risk factors have been investigated, there is limited information available stratifying them by injury location(e.g., trunk, head, or extremity) [11].This is especially true for pediatric upper extremity (UE) firearm injuries [12],which can be devastating due to anatomical complexity,often requiring multiple surgeries and extensive reconstruction by a qualified hand surgeon [13– 15].Due to these factors, this trauma contributes considerably to the high number of hospitalizations and healthcare costs seen in pediatric firearm injuries overall [9, 10].While limited to non-ballistic weapons, Summers et al.reported an annual average of 2895 pediatric UE firearm injuries in the United States requiring hospitalization [16, 17].This evidence further necessitates the need for additional literature specific to the UE.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate pediatric patients treated for UE powder and non-powder firearm injuries to identify at-risk populations and recurring mechanisms or circumstances related to these injuries.Ultimately, through elucidating potential trends, we hope to inform the future creation of targeted educational materials for these at-risk populations.

Methods

An Institutional Review Board-approved retrospective review of all patients cared for at our center for firearm injuries to the UE between January 1, 1999 and December 31,2019 was conducted using International Classification of Disease (ICD) codes associated with firearm injuries (W32-34, X72-74, X93-95, Y22-24, and Y35-36).Our institution,a tertiary, Level-I trauma center, includes a children’s hospital and adult hospital.Patient data within our adult and pediatric systems are maintained in one electronic medical record.Patients were included if they were < 17 years of age at the time of the shooting and the mechanism of injury was related to a firearm.The catchment area included both urban and rural patient populations.Using a standardized abstraction process and data collection form, three individuals reviewed the electronic medical record and collected data, which was stored on a secure database.Demographic variables including age, sex, race, ethnicity, past medical history, and county where the incident occurred were recorded.Additionally, firearm type (powder or non-powder) was collected.Non-powder weapons, also known as air rifles, included BB (a generic term for small spherical projectiles) guns and pellet guns.To differentiate patients based on social development, age categories were used(infant: 0–12 months; toddler: 12 months–2 years; early childhood: 2–5 years; middle childhood: 6–11 years; early adolescence: 12–17 years).To further assess physical and social maturity, the early adolescence group was split into two, 12–15 and 16–17.Next, anatomic locations of each firearm injury, resulting UE injuries, and procedures performed were recorded, and surgical data including complications were assessed.Additionally, information related to each shooting such as circumstances surrounding the event and the owner of the weapon used was documented, along with law enforcement involvement.Events were classified as accidental assault (accidental discharge of weapon into bystander), accidental discharge (accidental self-inflicted injury), intentional assault (purposeful discharge of weapon into bystander), and intentional self-inflicted injury.Finally,collected population data was compared to statewide pediatric population information using the 2010 Florida census to assess population composition [18].

Statistical analysis

All collected data were analyzed using descriptive statistics.Percentages and frequency counts were used to describe categorical variables, while means and standard deviations were reported for continuous variables.Additionally, patient-, surgical-, and treatment-related factors were analyzed using Fischer’s exact tests to assess differences in categorical variables.Due to large sample sizes,analysis including census information was completed using Chi-square tests with Yates’ correction.Statistical tests were two-sided, andPvalues less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.Microsoft Excel (Version 16.52, 2020)was used for all analysis.

Results

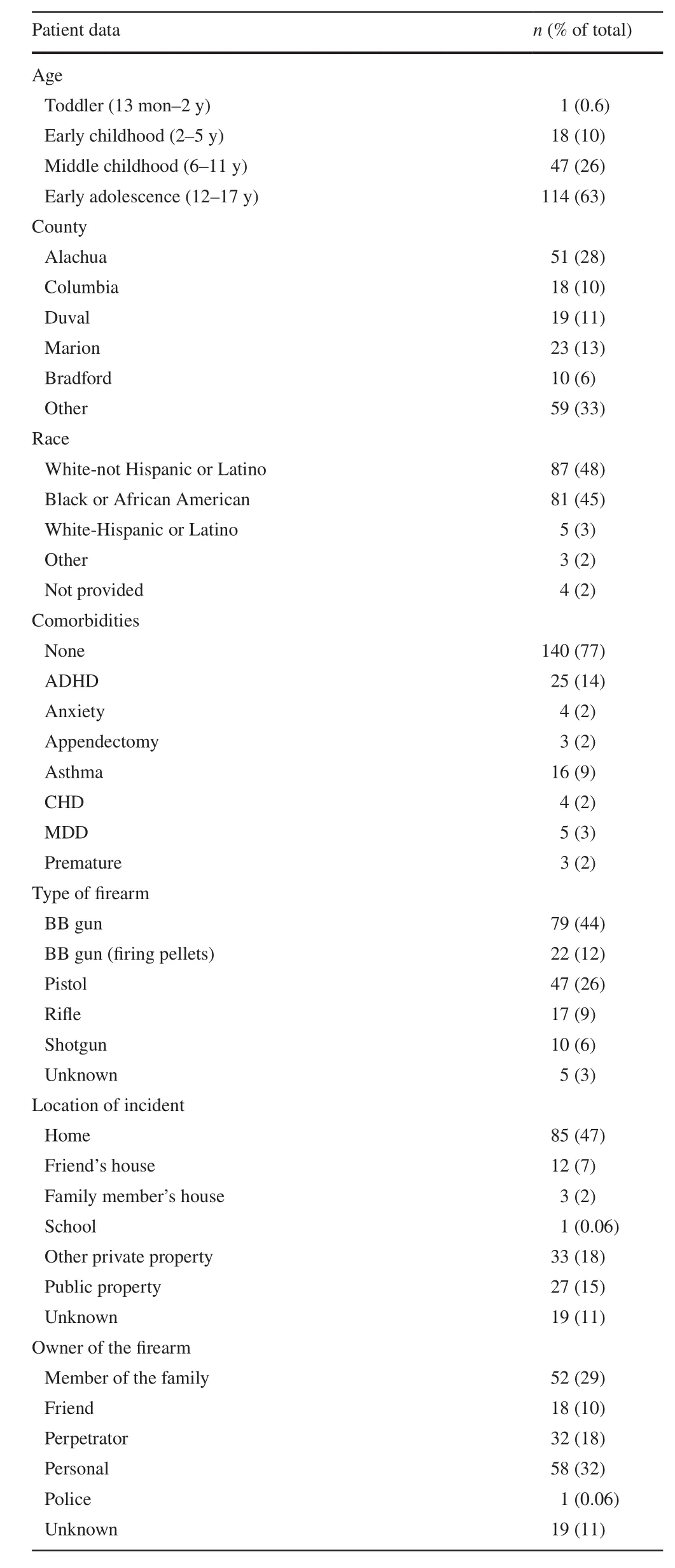

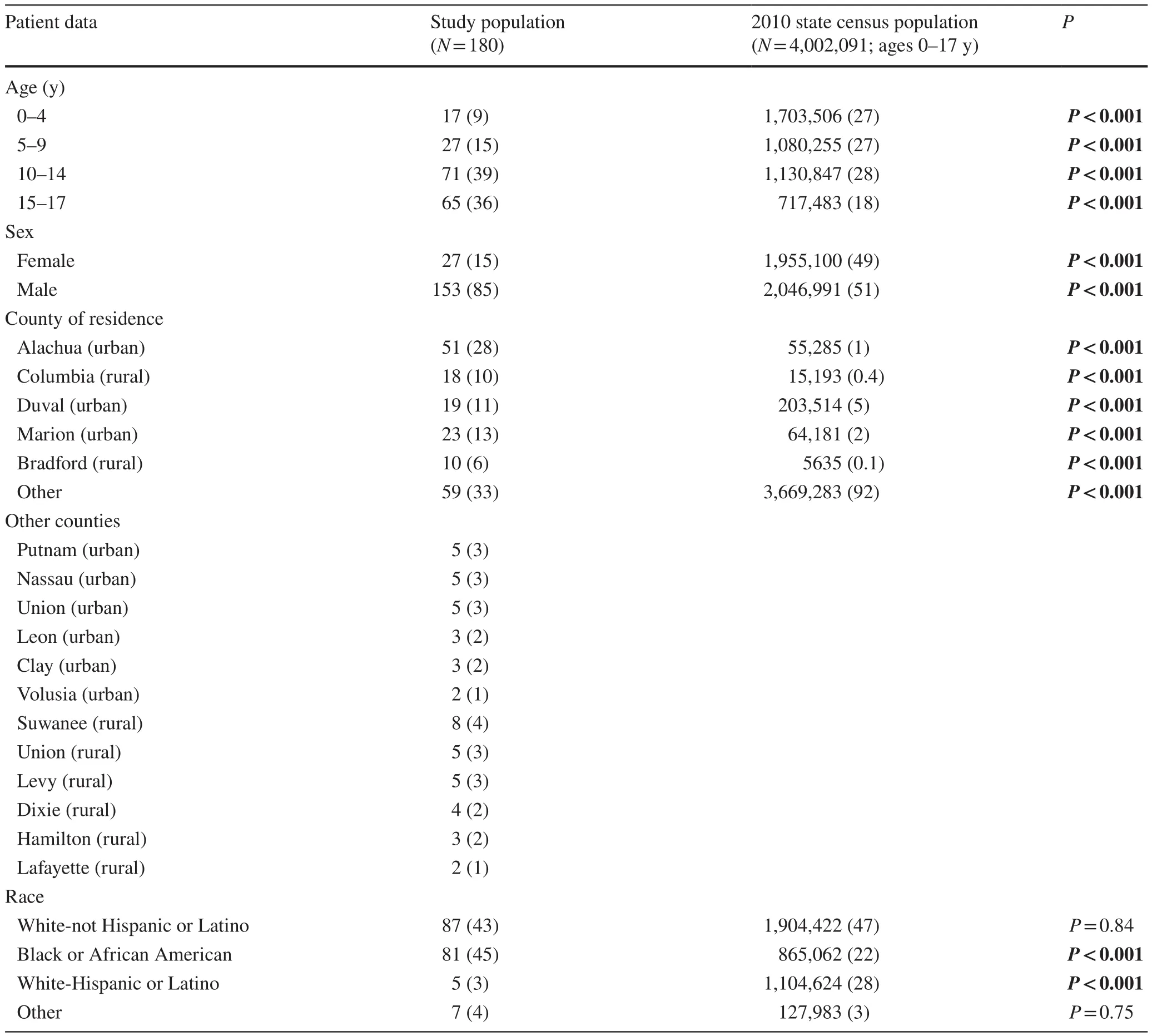

A total of 180 patients were included (Table 1).The majority were males (n= 153, 85%), between the ages of 12–17 years (n= 114, 63%).Thirty-eight percent (n= 68) were aged 12–15 years.The mean age was 12.04 years with a standard deviation of 4.32.Eighty-seven (48%) patients were White-not Hispanic or Latino and 81 (45%) were Black.Most patients had no comorbidities (n= 140, 68%).Air rifles firing BB ammunition were implicated in 79(44%) cases and air rifles firing pellets were implicated in 22 (12%).Pistols (n= 47, 26%) were also significant contributors to injury.Most incidents occurred at home(n= 85, 47%) or another location described as private property (n= 33, 18%) other than a friend’s house (n= 12,7%), family member’s house (n= 3, 2%), or school (n= 1,0.06%).These private property locations included gymnasiums, athletic complexes, and in several instances, were only described as “private land” in the electronic medicalrecord.The involved firearm was a personal weapon in most cases (n= 58, 32%) and belonged to a family member in 52 (29%) cases.Zip code, and the corresponding county where each incident occurred, was categorized as rural or urban based on classifications described in the 2010 Florida census.Per the census, counties are labeled“rural” if there are 100 persons or less per square mile.The opposite is true for “urban” zip codes.

Table 1 Summary of demographic data for pediatric patients with firearm injuries to the upper extremity ( N = 180)

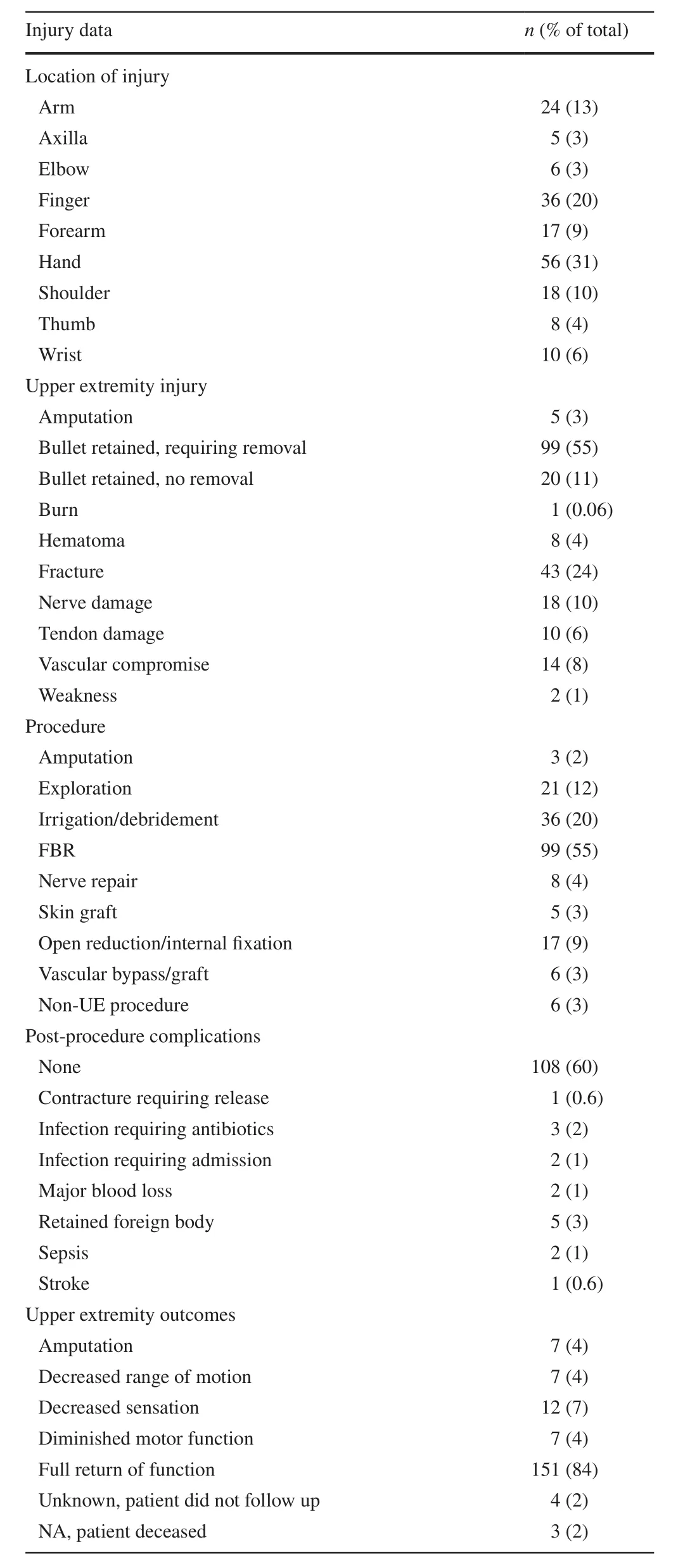

The hand was the most frequent location of injury (n= 56,31%) (Table 2).Finger (n= 36, 20%) and upper arm (n= 24,13%) were the next most common locations affected.In 99(55%) patients, projectile fragments were retained, requiring removal.Forty-three (24%) patients had fractures and 20(11%) had retained projectile fragments that did not require removal.Eighteen (10%) patients had nerve damage at presentation, 14 (8%) had vascular compromise, and 10 (6%)had tendon damage.Ninety-nine (55%) patients had procedures in the operating room, while 56 (31%) patients did not require a procedure.The most frequent procedure done was foreign body removal (FBR) (n= 99, 55%).One hundred and eight (60%) patients had no immediate complications following procedural repair, and 151 (84%) patients had full return of UE function.Twelve (7%) had decreased sensation in the affected extremity postoperatively, and 7 (4%) had diminished motor function.Law enforcement was involved in 72 (40%) cases, arrests were made in 17 (9%) cases, and charges were filed in 5 (3%) cases.

Table 2 Summary of injury data for pediatric patients with firearm injuries to the upper extremity ( N = 180)

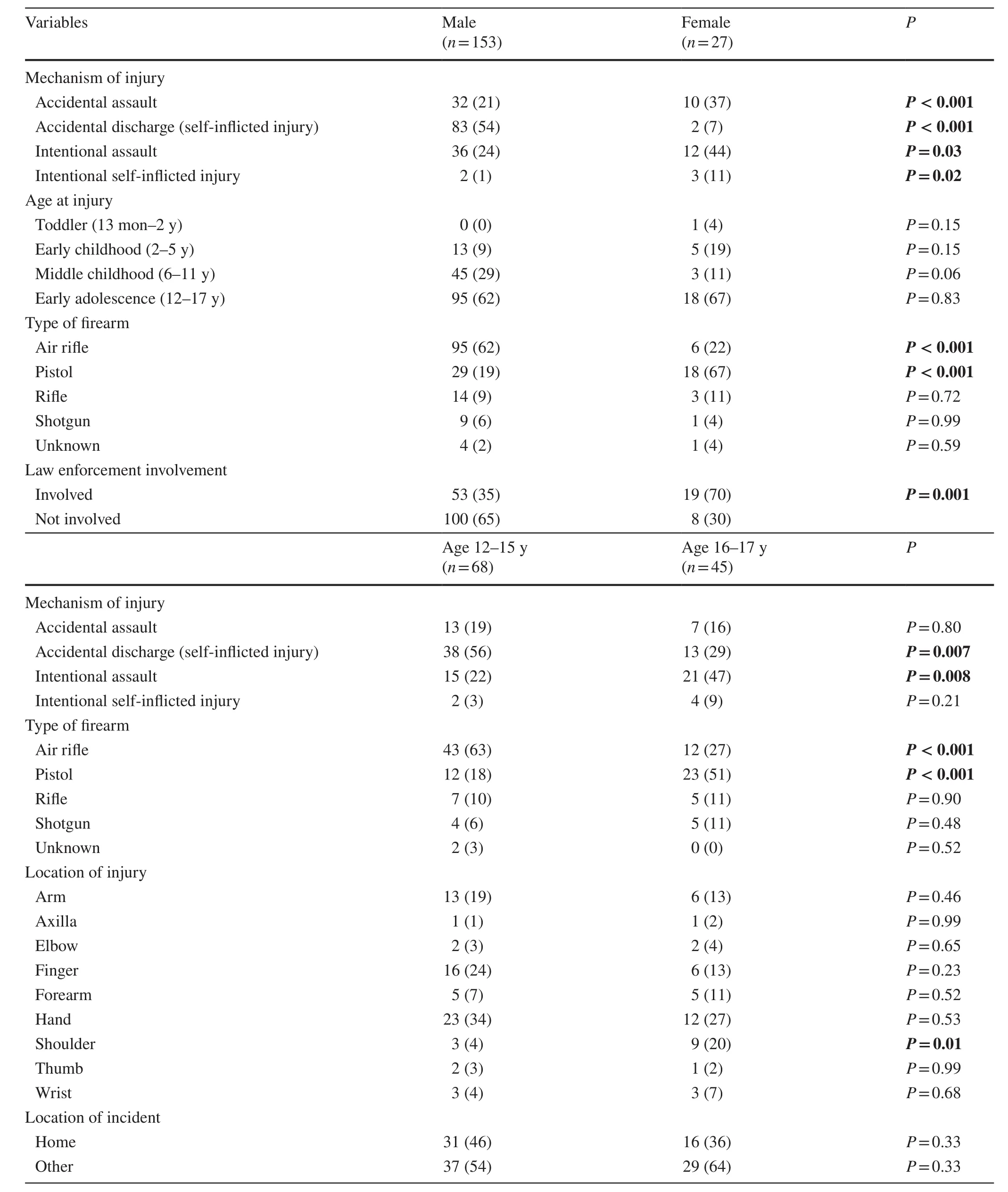

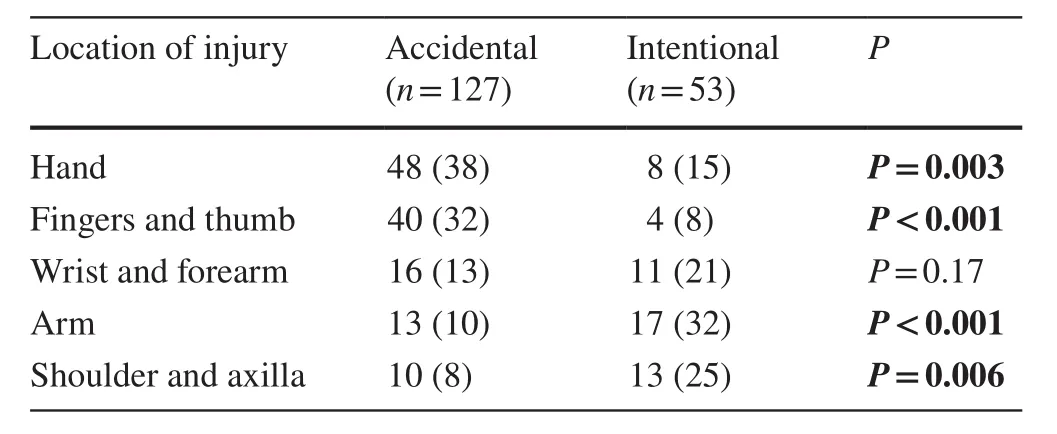

When comparing incidents involving males and females(Table 3), a higher percentage of females (n= 10, 37%)were injured due to accidental assault than males (n= 32,21%) (P< 0.001).This was also true for intentional assault(P= 0.03) and intentional self-inflicted injury (P= 0.02).Additionally, a higher percentage of females (n= 18, 67%)were injured by pistols than males (n= 29, 19%) (P< 0.001).On the contrary, a higher percentage of males (n= 83, 54%)were injured due to accidental discharge than females(n= 2, 7%) (P< 0.001).Furthermore, a higher percentage of males (n= 95, 62%) were injured by an air rifle compared to females (n= 6, 22%) (P< 0.001).There were no significant differences between males and females when stratified by age at time of injury or in injuries due to rifles and shotguns.Interestingly, law enforcement was signifi-cantly more involved in cases involving a female (n= 19,70%) (P= 0.001), due to the severity of these events.A greater percentage of wounds occurring to the hand were accidental (n= 48, 38%) as opposed to intentional (n= 8,15%) (P= 0.003) (Table 4).Meanwhile, a higher percentage of injuries to the arm and shoulder/axilla were intentional(P< 0.001;P= 0.006).

Table 3 Summary of firearm injury data stratified by sex and age for pediatric patients with firearm injuries to the upper extremity ( N = 180)

Table 4 Summary of location of injury by mechanism of injury for pediatric patients with firearm injuries to the upper extremity( N = 180)

To account for known behavioral and skeletal maturity in the early adolescence group, common demographic factors were stratified by age and assessed.Patients aged 12–15 years were proportionally more injured by accidental discharge (P= 0.007) than patients aged 16–17 years.The latter were more injured by intentional assault (P= 0.008).Additional significant associations were determined for various firearms in these two age groups (Table 3).

Finally, to further determine at-risk populations, our study population was compared to 2010 state census data consisting of 4,002,091 children aged 0–17 years(Table 5).Notably, the present study included a signifi-cantly larger proportion of males (P< 0.001) and Black children (P< 0.001) than the state.Meanwhile, White children were affected at a rate not significantly different from their representation in the state (P= 0.84), and Hispanic/Latino children were affected less frequently (P< 0.001).Children aged 10–14 (P< 0.001) and 15–17 years(P< 0.001) made up significantly larger proportions in this study population compared to the state population,while children aged 0–4 and 5–9 years were underrepresented compared to the census (P< 0.001;P< 0.001).Of the total, 116 (64%) patients came from urban areas and 64 (36%) from rural areas.Interestingly, 78% of total powder firearm injuries occurred in patients from urban areas (P= 0.001).On the contrary, 48% of total non-powder injuries occurred in patients from rural areas; this is statistically significant (P= 0.03).

Table 5 The demographic data comparison between this study and 2010 Florida State census

Discussion

Firearm injuries, while potentially lethal in all populations,are known to cause significant morbidity and mortality in pediatric patients [19].In particular, these injuries to the UE have been linked to increased operative complexity,lengthy hospital stays, and long-term complications [20].Despite this, little is known regarding specific risk factors and recurring mechanisms for these injuries.In one series by Dabash et al.10 cases involving UE firearm injuries in patients under the age of 18 were reported [12].Of those,most patients were male (70%), and only three were under the age of 5 (30%).Greater than half of the injuries were the result of violence (60%), with the vast majority involving a powder firearm (80%) [12].In the present study, we also found males to be more frequently affected (n= 153,85%) when compared to females (n= 27, 15%), and most patients included were older than 5 years of age (n= 162,90%).In our series, however, most cases were the result of accidental harm (n= 127, 71%), involving non-powder weapons (n= 101, 56%).These discrepancies are likely due to variations in patient population and regional gun restriction policies.It is also possible that the Dabash et al.study was influenced by regional conflict and instability.

While insufficient literature specific to pediatric UE firearm injuries limits qualitative comparisons, the frequency of unintentional firearm injuries in this study resembles literature analyzing pediatric firearm injuries as a whole [21].In a national study observing firearm-related injuries not specific to the UE, Powell et al.found most firearm injuries in children aged 0–14 years to be unintentional, with most injuries in children aged 15–19 years to be purposeful (n= 78,968, 56%) [14].Overall, as determined by Powell et al.more patients were harmed due to unintentional actions as opposed to purposeful assault (n= 104,561, 43%;n= 95,809, 39%), similar to the present study [14].Interestingly, opposed to our study, Powell et al.found a greater frequency of powder firearm injury (n= 137,093, 56%)compared to non-powder injuries (n= 107,729, 44%).In our study, the greater rates of non-powder injury (n= 101,56%) can likely be attributed to geographic differences and relaxed restrictions surrounding air rifle purchase in the state of Florida [5, 22].As there are no federal safety standards for non-powder firearms, it is important to acknowledge regional variation in firearm injury patterns.The present study potentially elucidates the need for increased state or federal safety legislation for non-powder weapons.

While not specific to the UE, a study conducted by Parikh et al.analyzing firearm injuries in pediatric patients nationally reports similar findings as those discussed in Powell et al.and the present study.Parikh et al.determined rates of unintentional firearm injuries to be increasing in pediatric patients, with younger children (aged 0–15 years) to be at greater risk for unintentional injury as opposed to assault.Additionally, they determined older children to be at a much higher risk for firearm injury [19].Fowler et al.also found a greater frequency of firearm-related injuries in older populations (13–17 years;n= 6174, 87%) [9].Similarly, in the present study, the majority (n= 113, 63%) of firearm injuries occurred in older children (aged 12–17 years).In this group, patients aged 16–17 years were more often victimized by pistols (P< 0.001) and assault (P= 0.008).Meanwhile,patients aged 12–15 years were more often victimized by air rifles (P< 0.001) and accidental discharge (P= 0.007).There were no differences between the two groups regarding the location the shooting occurred.These differences can likely be attributed to behavioral factors—older adolescents have greater access to powder weapons due to their ability to legally drive an automobile, while younger individuals typically have more adult supervision [9].

Interestingly, while most patients in this study had no history of medical illness, 25 (14%) had a documented history of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).This was by far the most common comorbidity seen.To our knowledge, there is no known literature discussing an association between ADHD and pediatric firearm injuries [23].

Comparison to state census

Importantly, the present study population differed from the 2010 Florida census data for children aged 0–17 years in several areas of interest.The higher proportion of males in our study population (85%) compared to the state population(51%) is likely due to males being more frequently involved in activities involving firearms.The overrepresentation of teenage children in our study could also be explained by children in their teenage years being more involved in activities involving firearms than younger individuals.Additionally, due to our catchment area, the overrepresentation of the surrounding counties (Alachua, Columbia, Duval, etc.)compared to state data was expected.Finally, while no available studies specifically analyze demographic distributions in our region, the study population included a high percentage of residents in rural areas.It is possible these populations have racial distributions different than the state, which includes several, highly populated metropolitan areas.These differences could be responsible for the racial make-up of this study population.

Incident location

In this study, most UE firearm injuries occurred at home(n= 85, 47%), with weapons owned by the victim (n= 58,32%) or a family member (n= 52, 29%).Likewise, out of 277 events involving firearm injuries not specific to the UE, Faulkenberry et al.found 77% (n= 211) to occur at home or in a family member’s home [24].In almost all events, the injury was self-inflicted (n= 233, 84%), and in instances where reported, with a gun owned by a family member (68%).This is similarly documented throughout the literature.

While information regarding the type of home (farm,apartment, condominium, etc.) is unknown in all cases, the 2010 Florida census provided insight into population density where each injury occurred (Table 4).Differences regarding powder firearm injuries in the urban population and nonpowder firearm injuries in the rural population, can likely be attributed to different recreational activities.Additionally, it is well-established that violent, powder-weapon crime rates are higher in urban settings [5].

Male and female differences

While males were more frequently victims of UE firearm injury in this study overall, females were more likely to be injured due to intentional assault (P= 0.03) and intentional, self-inflicted injury (P= 0.02).Males were more likely to be injured due to accidental assault (P< 0.001) and self-inflicted, accidental discharge (P< 0.001).Interestingly,Fowler et al.found males to be more frequently injured in firearm-related homicides, suicides, and unintentional injuries [9].Barry et al.also reported increased rates of unintentional firearm injuries in males compared to females,however, these studies are not specific to UE injuries [25].Additionally, in our study, more males were injured by nonpowder weapons (n= 95, 62%) compared to females (n= 6,22%) (P< 0.001), and more females were injured by pistols(n= 17, 63%) compared to males (n= 29, 19%) (P< 0.001).Qualitatively, most cases included in this study were males that accidentally discharged a non-powder weapon into their hand while hunting or shooting at targets.Females were less frequently brought to the ED with these injuries, possibly because they are less likely to partake in these types of activities.When considering this, the increased frequency of unintentional injuries in males and seemingly increased frequency of more serious injuries in females is explained.Furthermore, in this study, cases involving females more frequently involved law enforcement (males:n= 53, 35%;females:n= 19, 70%) (P= 0.001).When considering that females were more frequently injured with high-powered weapons, potentially because they avoid non-powder weapon activities, it is reasonable to observe increased law enforcement activity.This topic was included in this discussion as further evidence of this theory.

Anatomic site of injury

In this study, the most common sites of injury were the hand(n= 56, 31%) and the fingers (n= 36, 20%), not including the thumb.Injuries to the hand (P= 0.003) and fingers/thumb(P< 0.001) were more likely due to accidental mechanisms as opposed to purposeful assault.On the contrary, injuries to the shoulder/axilla (P= 0.006) and arm (P= 0.007) were more likely due to assault, rather than unintentional mechanisms.When considering UE-specific firearm injuries, it is not unusual that most injuries occur to the hand/fingers due to accidental firearm discharge.Improper reloading,cartridge/magazine changing, and holstering are all more likely to injure the hand as opposed to other UE locations[26].Meanwhile, due to anatomical orientation, it is more difficult to accidentally discharge a firearm into a shoulder,arm, or axilla.When considering this, it is reasonable to expect most of these injuries to occur due to assault or purposeful mechanisms.

Treatments

While debate exists regarding the utility of FBR in firearm injuries due to concerns over projectile fragmentation and excessive iatrogenic tissue injury from debridement, this study noted FBR in 55% of patients [27].Typically, highvelocity injuries require debridement and retained projectile removal unless surgery would result in unnecessary soft tissue dissection.It is possible that injuries in this cohort were more readily explorable for FBR because of their location in the UE (mostly hand and fingers) rather than a body cavity.It is also possible that the increased rate of FBR in this cohort was due to the high number of air rifle injuries.These projectiles do not fragment and are often super ficial, making them easier to access [28].This also potentially explains why serious UE injury requiring additional procedures (tendon,vasculature, and nerve), post-procedure complications, and long-term deficits were infrequent in this study population.

Limitations

Although this study evaluated pediatric patients over a lengthy, 20 year time period, there are limitations worth mentioning.Most notably, this was a retrospective review and is vulnerable to misclassification bias in instances where data is not clearly indicated in the medical record.Additionally, in the context of a lack of high-quality national databases containing granular information regarding firearm,incident, and injury, this was a single-institution review, and therefore had limited sampling.This study does not include patients who may have been treated at regional medical centers and is limited to the demographics of the local area.Finally, with such a paucity of literature pertaining to pediatric UE gunshot wounds in general, there is limited comparative data for which to draw conclusions.

In conclusion, pediatric firearm injuries remain an understudied topic that will benefit from continued attention to further identify and characterize at-risk populations and circumstances associated with these serious events.As most of these firearm injuries occurred at home, future studies could investigate for any characteristics of a home that contribute to firearm injury prevalence, type, or severity.This study is unique compared to available literature in that it is the only known analysis to date that specifically identifies and evaluates risk factors for pediatric firearm injuries of the UE.Detailed and specific characterization of these injuries, as well as associated outcomes, will help to aid in future prevention and treatment optimization.Moreover, the information obtained in this study could be used to create an education campaign to target at-risk populations in our region and beyond.

Author contributionsNDS contributed to conceptualization, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, writing of original draft, reviewing and editing.AM contributed to conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, and writing of original draft.KC contributed to conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis,investigation, writing of original draft, reviewing and editing.KD and CH contributed to conceptualization, writing of original draft, reviewing and editing.SE contributed to conceptualization, methodology,formal analysis, investigation, writing of original draft, reviewing and editing, and supervision.All authors contributed to final approval of this manuscript.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant or funding from agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethical approvalThis investigation was IRB approved (IRB 201903454) by the University of Florida.Specifically, the study was awarded exempt approval.For all patients undergoing treatment at the University of Florida, consent was obtained from the patient (or their parent or legal guardian in the case of children under 16) for treatment and the inclusion of data for retrospective research.

Conflict of interestNofinancial or non financial benefits have been received or will be received from any party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Data availabilityThe datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to included participants’privacy but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

World Journal of Pediatrics2021年5期

World Journal of Pediatrics2021年5期

- World Journal of Pediatrics的其它文章

- Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis as a manifestation of Kawasaki disease

- Febrile infants: written guidelines to reduce non-essential hospitalizations

- Rising serum potassium and creatinine concentrations after prescribing renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system blockade:how much should we worry?

- Role of ultrasound in the diagnosis of cervical tuberculous lymphadenitis in children

- Nasogastric or nasojejunal feeding in pediatric acute pancreatitis:a randomized controlled trial

- Serum vitamin E concentration is negatively associated with body mass index change in girls not boys during adolescence