Nasogastric or nasojejunal feeding in pediatric acute pancreatitis:a randomized controlled trial

Hong Zhao ·Yan Han ·Ke-Rong Peng ·You-You Luo ·Jin-Dan Yu ·You-Hong Fang ·Jie Chen ·Jin-Gan Lou

Abstract

Background The aim of this study was to compare nasogastric (NG) feeding with nasojejunal (NJ) feeding when treating pediatric patients with acute pancreatitis (AP).

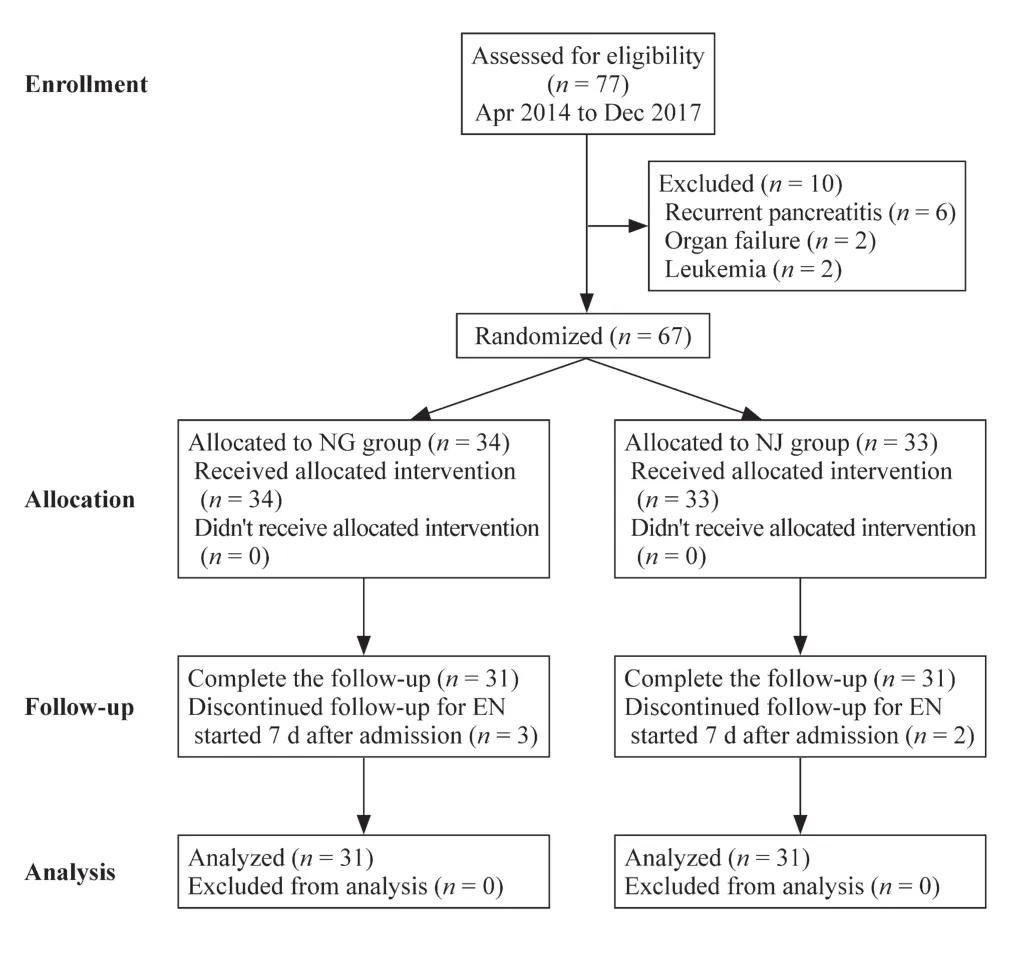

Methods We performed a single-center, prospective, randomized, active-controlled trial involving 77 pediatric patients with AP from April 2014 to December 2017.The patients were randomized into two groups: the NG tube feeding group (34 patients) and the NJ tube feeding group (33 patients).The primary outcome measures included the enteral nutrition intolerance, the length of tube feeding time, the recurrent pain of pancreatitis and complications.

Results A total of 62 patients with AP (31 patients for each group) came into the final analysis.No differences were found in baseline characteristics, pediatric AP score and computed tomography severity score between the two groups.Three (9.7%)patients in the NG group and one (3.2%) patient in the NJ group developed intolerance (relative risk = 3.00, 95% confidence interval 0.33–27.29, P = 0.612).The tube feeding time and length of hospital stay of the NG group were significantly shorter than those of the NJ group ( P = 0.016 and 0.027, respectively).No patient died in the trial.No significant differences were found in recurrent pain, complications, nutrition delivery efficacy, and side effects between the two groups.

Conclusions NG tube feeding appears to be effective and safe for acute pediatric pancreatitis compared with NJ tube feeding.In addition, high qualified, large sample sized, randomized controlled trials in pediatric population are needed.

Keywords Acute pancreatitis ·Enteral nutrition ·Enteral nutrition intolerance ·Length of hospital stay ·Tube feeding time

Introduction

An increasing incidence of acute pancreatitis (AP) in children has been reported in the past decades [1, 2],with 0.78–13.2 cases per 100,000 pediatric individuals per year depending on existed estimates [3– 5].Initially,the main method of nutrition management during the AP process was intravenous fluids, which was believed that resting the pancreas could reduce stimulation and limit pancreatic exocrine function.However, multiple studies in adults have illustrated that early enteral feeding(EN) is well tolerated and, when compared to fasting and parenteral nutrition, is significantly beneficial in terms of mortality, complications and length of hospital stay[6– 9].Existing studies and guidelines for adults have recommended early EN in AP [10– 13].Research studies on adults have led to dramatic changes from initially complete bowel rest to early enteral nutrition for both adults and children.A single-center, retrospective report has reported a significant increase in the proportion of patients who received early enteral nutrition after June 2014 compared with before June 2014 (69 vs.25.4%)[14].Only one recent randomized trial on children has revealed that there is no significant difference between early feeding and initial fasting in terms of prognosis or complications [15].Although recent pediatric recommendations have supported early feeding in pediatric AP, these recommendations are based mainly on adult guidelines and on limited retrospective data from children[16– 18].Hence, methods for regulating the nutrition management for AP in children are important and necessary.

It is believed that EN should be started as early as tolerated, whether through oral, nasogastric (NG), or nasojejunal (NJ) routes for both adults and children [13, 16, 19].Compared to oral feeding, tube feeding is a better way to manage the speed and quantity of nutrients.Our previous study already focused on EN treatment and revealed that NJ feeding was feasible and effective in children with AP [20].Studies in adults have shown that NG feeding is safe, welltolerated and not inferior to NJ feeding [21, 22].Notably, a NG tube can be placed easily by clinicians at bedside without assistance of endoscopy or radiation exposure, making it easier to be accepted than a NJ tube in pediatric patients.Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the safety and efficiency of NG nutrition in children with AP compared with NJ nutrition.

Methods

A single-center, prospective, randomized, active-controlled trial was conducted at a tertiary center, the Children’s Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine in China, from April 2014 to December 2017.It was impossible to blind the trial due to the nature of the EN route.The participants were patients from the gastroenterology clinic, who were diagnosed with AP and required hospitalization.

The study was approved by Ethics Committee of the Children’s hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine and was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.The purpose of the study was explained clearly to all enrolled patients and their legal guardians,and their informed written consents were obtained.The trial was registered at Chinese Clinical Trial Registry(ChiCTR-TRC-14004511).

Criteria

The inclusion criteria included: (1) diagnosed with AP; (2)age between 2 and 18 years; (3) informed consent signed by their legal guardians.The definition of AP requires at least two of the following: (1) abdominal pain compatible with AP; (2) serum amylase and/or lipase values ≥ 3 times upper limits of normal; (3) imaging findings of AP [23].

The exclusion criteria included: (1) diagnosed with recurrent pancreatitis, which defined as acute recurrent pancreatitis and chronic pancreatitis [23]; (2) AP with single/multi-organic dysfunction, respiratory distress, shock,gastrointestinal bleeding, immune deficiency, etc.; (3) predicted severe or necrotizing AP, which had signs associated with organ failure, required intensive care unit admission or EN contraindications; (4) EN support was administered later than 7 days after admission; (5) nutritional therapy was started before randomization; (6) enrolled into other trials within 6 months; (7) any other conditions restricting EN therapy or tumor.

Study design

All the patients were 1:1 randomized into two groups:the nasogastric feeding group (shortened as “the NG group”)and the nasojejunal feeding group (shortened as “the NJ group”).Randomization sequences were generated by SAS 9.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) from the statistician.The study started immediately after randomization.Patients in the NG group received EN therapy via the NG tube (Flocare® NG tube, Nutricia, Wuxi, China), which was placed at the bedside in the ward with the position confirmed by aspiration,and radiography.Patients in the NJ group received EN therapy via the NJ tube (Flocare® NJ tube, Nutricia, Wuxi,China), which was placed in the jejunum beyond the ligament of Treitz under endoscopic guidance and confirmed radiologically.The endoscopy was performed the day before the EN began, and whether to administer anesthesia was decided by the guardians.Peptamen (Nestle China Ltd,Beijing, China), a commercially available semi-elemental enteral formula, was used as the only nutrient for both groups.The standard of nutrient goal of individuals was uniform, which was calculated and confirmed by clinical nutritionist based onNelson Textbook of Pediatrics[24].The maximum goal was no more than 2000 kilocalorie per day.In the adult trial, the researchers made a time limit of 3–4 days for patients to reach the nutrient goal via tube feeding [22].Considering the lower tolerance of children, we limited the time to reach the nutrient goal as 5 days, with an average increase of about 20% per day.

The therapeutic principles and nutritional management for AP were consistent in both groups.Detailed baseline characteristics and clinical data were recorded, including blood routine examination, electrolytes, blood glucose, renal and liver function tests, serum amylase and lipase, and arterial blood gas analysis.Contrast-enhanced, computed tomographic scanning of abdomen was used initially to assess the presence of fluid collections and necrosis.Pediatric acute pancreatitis score (PAPS) and computed tomography severity score (CTSI) were calculated to evaluate the severity of AP [25, 26].Antibiotics were prescribed if patients had evidences of pancreatic necrosis or extra-pancreatic infection.The antibiotics were selected by experience, or by microbial culture and drug sensitivity results if available.EN was started for all patients within 7 days after admission if patients had no contraindications, which mainly included persistent vomiting, abdominal distension or active gastrointestinal bleeding.Once the cause had been identified,appropriate measures were taken if the condition permitted.An endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERCP) would be supplied for patients with biliary obstruction, cholangitis or pancreatic duct dilation.Endoscopic stone extraction was performed for patients with cholelithiasis and choledochocystectomy for those with choledochal cyst.Ultrasound was used to assess pancreatic recovery during the trial when necessary.

Total parenteral nutrition (TPN) was introduced in patients who developed intolerance.If the patient developed symptoms such as abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhea,the rate of EN feeding would be reduced by half.After adjusting, patients with remission continued EN therapy, but those without remission or with exacerbation of symptoms were determined as intolerant.A fasting and TPN would be started for intolerant patients.

Oral feeding could be restarted once patients had no abdominal pain with no distension or vomiting for two consecutive days.When oral feeding was well-tolerated, the NG/NJ tube would be removed.Our follow-up ended when the EN tube was removed.Patients were monitored and were recorded daily for intolerance, gastrointestinal symptoms,nutrition supply, recurrence of pain and complications.

Outcome measures

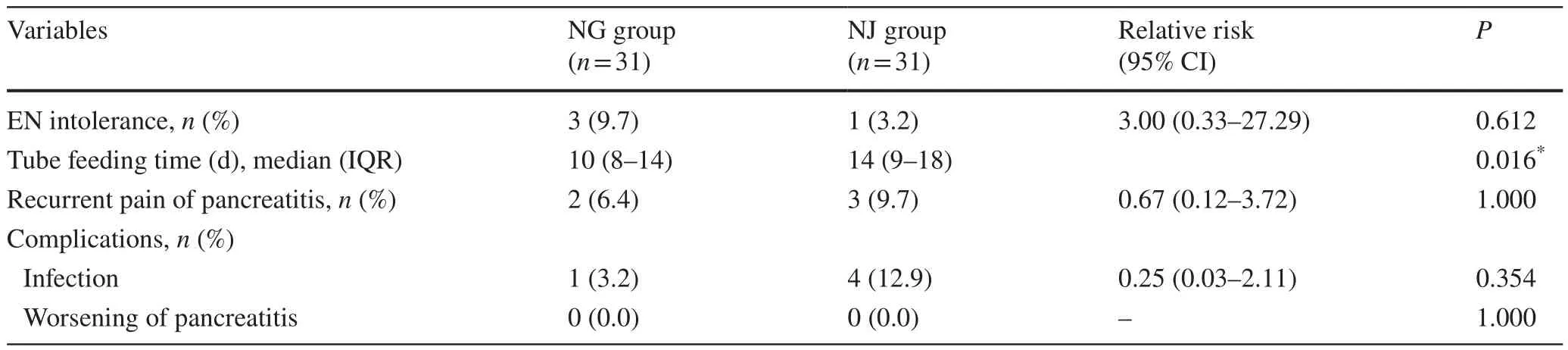

The primary outcome measures included the EN intolerance, the total length of tube feeding time, the recurrent pain of pancreatitis and complications.The recurrent pain of pancreatitis was defined as a re-occurrence of abdominal pain requiring stopping feeding and was associated with an increase in serum amylase and/or lipase at least twice the previous value [22].Complications included infection and worsening of pancreatitis, which corresponds to an evaluation of disease progression from mild–moderate to severe,even with signs of necrosis.

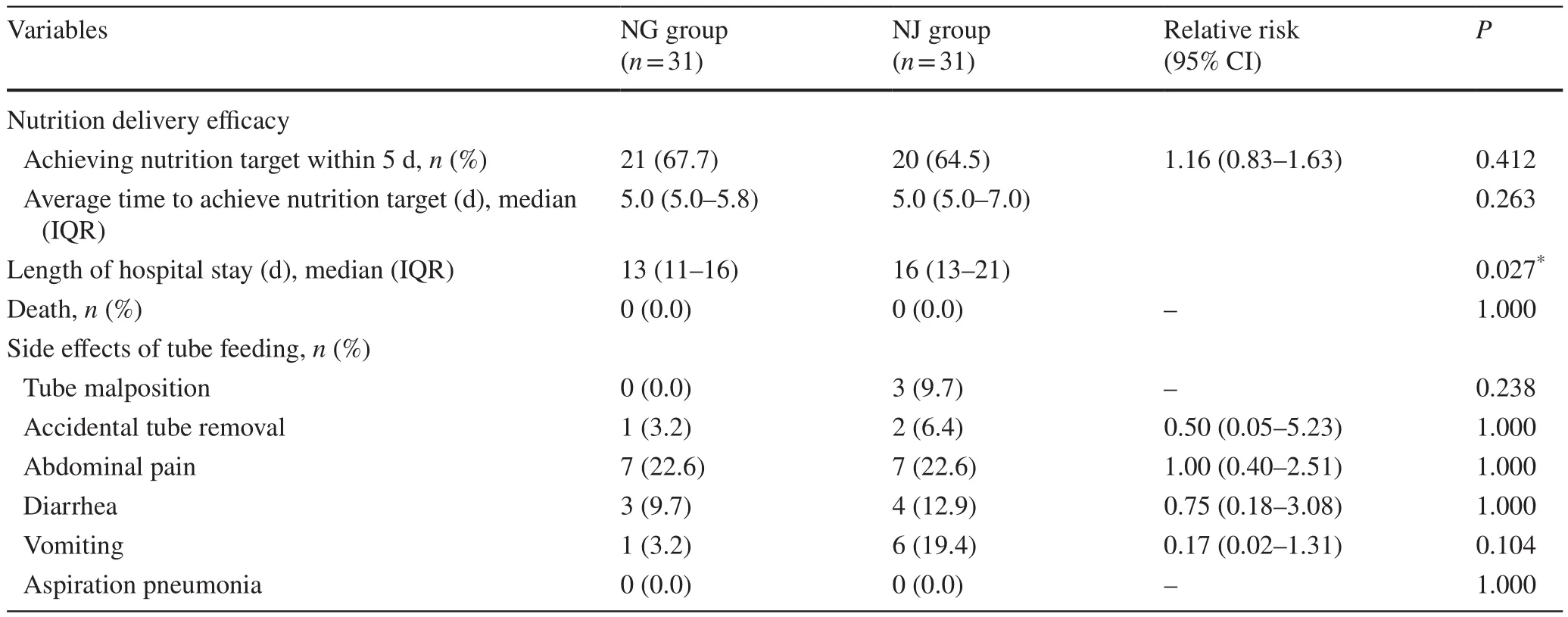

The secondary outcome measures mainly included nutrition delivery efficacy, the length of hospital stay,mortality, and side effects.The nutrition delivery efficacy included whether to achieve the nutrient goal within 5 days and the average time to reach the nutrient goal.The major side effects included tube malposition, accidental tube removal, abdominal pain, diarrhea, vomiting, and aspiration pneumonia.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted with blinding to EN routes.The statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 26.0(SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).Categorical variables were presented as frequencies with percentage and were compared using Pearson’s Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test.Continuous variables having a normal distribution were presented with means and standard deviations and were analyzed using Student’sttest.Continuous variables having a non-normal distribution were presented with medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) and were analyzed using Mann–WhitneyUtest.Differences were presented as relative risk (RR) [95% confidence interval (CI)] between the treatment groups.P< 0.05 (2-tailed) was considered statistically significant.

Results

Participant characteristics

Of 77 patients assessed during the 44 months, 67 patients were eligible for enrollment in the study.They were randomly assigned into two groups, with 34 in the NG group and 33 in the NJ group.During the trial three patients in the NG group and two patients in the NJ group were excluded due to delay of starting EN feeding (Fig.1).As a result, 62 participants completed the protocol, with 31 patients in each group.There were no differences between the two cohorts in demographic and anthropometric characteristics, laboratory information, PAPS and CTSI scores at presentation(Table 1).Etiologies were analyzed in the study, but nearly half (48.4%) of the cases were unclear and were classified as idiopathic, with 14 in the NG group and 16 in the NJ group.There were no significant differences between the two groups in etiologies (Table 1).

Fig.1 Enrollment, randomization and follow-up of this study

Table 1 Baseline demographic and clinical parameters in the study subjects

Primary outcomes

There was no difference found in enteral nutritional intolerance between the two groups.Three (9.7%) patients in the NG group and one (3.2%) patient in the NJ group developed intolerance and were switched to TPN (RR = 3.00, 95% CI 0.33–27.29,P= 0.612).A total of 22 (71.0%) patients in the NG group and 19 (61.3%) patients in the NJ group were able to fully tolerate without reducing feeding (P= 0.592).The tube feeding period was significantly different between the groups, with a median time of 10 days (IQR 8–14) in the NG group and 14 days (IQR 9–18) in the NJ group (P= 0.016).Two patients in the NG group and three patients in the NJ group had recurrent pain of pancreatitis, which was not associated with any significant rise in serum amylase and/or lipase, or worsening of pancreatitis.There was no difference found in complications about infection or worsening of pancreatitis between two groups (Table 2).

Table 2 Comparison of the primary outcome measures for different enteral nutrition measures

Secondary outcomes

Twenty-one (67.7%) patients in the NG group and 20(64.5%) patients in the NJ group achieved the nutrient goal within 5 days (P= 0.412).The median time to complete the nutrient goal was 5 days (IQR 5–5.8) in the NG group and was 5 days (IQR 5–7) in the NJ group(P= 0.263).All patients in the NG group and 28 (90.3%)patients in the NJ group achieved the nutrient goal eventually.In all of these patients, there was no difference found in nutrition delivery efficacy between the two groups(Table 3).The length of hospital stay was significantly shorter in the NG group with a median time of 13 days(IQR 11–16) compared with 16 days (IQR 13–21) in the NJ group (P= 0.027) (Table 3).No significant changes of serum amylase, serum lipase and C-reactive protein were found between the two groups.

Table 3 Comparison of the secondary outcome measures for different enteral nutrition measures

Overall, the most common side effect associated with tube feeding was abdominal pain.No serious side effects,such as aspiration pneumonia, occurred.Subgroup analysis for side effects showed no significant difference between the groups, but the NG group was numerically less than the NJ group (Table 3).

Safety

No fatal event occurred during the trial.All participants were shifted to oral feeding successfully, and the feeding tubes were removed eventually.Notably, the shortest tube feeding time was 6 days, and the longest was 42 days.The latter was present in the NJ group with persistent abdominal distention and recurrent vomiting, which we hypothesized might be related to the compression caused by the pancreatic pseudocyst.Taken together, these results suggested that both NG and NJ feeding were safe.

Discussion

Most studies regarding AP and nutritional support have been conducted in the adult population, with limited evidence in children.A previous clinical survey showed only 44% of pediatric gasteroenterologists would “often” use enteral tube feeding in AP management [23].Our previous study has already indicated that NJ nutrition therapy is effective and safe for pediatric patients with AP [20] and has revealed the benefits of enteral nutrition over fasting.A recent randomized controlled trial in 33 children has demonstrated no difference between early commencement of a full-fat diet and initial fasting with a subsequent low-fat diet [15].However, prospective data on nutritional management for pediatric AP remain scarce.Compared with oral feeding,tube feeding has advantages in precise control for nutrient volume and speed; however, not much is known about the differences between the two tube feeding methods in children.Our study demonstrates the NG tube feeding is safe and feasible as well as NJ tube feeding.NG tube placement is simple and cost-effective, making NG feeding a more desirable treatment strategy than NJ feeding for acute pediatric pancreatitis.

NG feeding has been confirmed as well-tolerated in adults with AP [21, 27, 28].Our study illustrates that NG tube feeding is well tolerated in children too.Intolerance occurred in both groups, but most occurrences were mild and were relieved by intervention.A totally of four patients were judged to be intolerant and were switched to TPN, three of whom received invasive operations to deal with underlying causes (two had choledochal cyst, one had choledocholithiasis).We suspect that the invasive operations may have caused intolerance.However, many factors are related to increased intolerance, such as systemic inflammatory response syndrome, pancreatic infection, and the time from admission to commencing EN [29].The real causes for developing intolerance about tube feeding need to be explored.

Our trial shows that the NG group had a significantly shorter time of tube feeding and a shorter length of hospital stay.Previous studies have reported that NG feeding is not inferior to NJ feeding [30, 31], but ours seems to show that NG feeding is more advantageous than NJ feeding in some ways.EN preserves intestinal mucosal integrity, prevents deterioration of the immune function of the intestine, and limits bacterial translocation in AP [32], thus decreasing the rate of organ failure and surgical intervention.We propose that differences between the two groups may be due to the continuous work of the stomach during NG feeding,which can promote gastric peristalsis, reduce the intensity and duration of abdominal pain and the risk of oral refeeding intolerance.These effects are conducive to shortening the tube feeding time and the length of hospital stay.Additional research is needed to uncover the truth.However, the length of hospital stay is about 4 days for pediatric patients with AP [33], which is shorter than our findings.There were two main reasons: first, due to original design, the feedings were monitored strictly.Once a patient developed symptoms related to intolerance, the EN feeding would be reduced by half.When the symptoms were relieved, the feeding could be increased slowly by about 20% per day.Second, we treated both the disease and the causes during a hospital stay.Of all patients, six were performed ERCP to identify the etiology.Four patients with choledocholithiasis underwent endoscopic stone extraction and five with choledochal cyst underwent choledochocystectomy.Invasive procedures prolonged the average length of hospital stay.

We find no differences between groups in terms of recurrent pain, complications, nutrition delivery efficacy.In other words, NG route is not worse than NJ route in pediatric AP.No other studies have been reported similar consequences in pediatric patients.Our study is consistent with researches in adults [30, 31], which provide the evidence for using EN in pediatric patients.

In our study the top three side effects associated with tube feeding were abdominal pain, diarrhea, and vomiting.A prospective study illustrated no differences regarding complications between adult patients with a NG or a nasointestinal tube, and the common complications were exacerbation of pain, vomiting and diarrhea [34].Our findings demonstrate similar safety of NG and NJ feeding in children.

Our study has several limitations that need to be acknowledged.First, the randomized trial only focused on the effect of different tube feeding methods.Pancreatitis was mild to moderate in all cases.Oral intake rather than tube feeding is appropriate for many patients with mild pancreatitis, and more rapid feeding advancement is often safe and welltolerated.While supporting the equivalency of NG vs.NJ feedings, our findings do not imply that tube feedings are required for the majority of pediatric patients with mild pancreatitis.Second, there was a delay in commencing EN.Published research have showed that an early start of ENs through NG and NJ tube, especially within 48 hours,is beneficial to AP and makes sense to shorten the length of hospital stay [18, 22, 35].The delay in our study occurred mainly because our center is a tertiary care center and most patients therefore were referred from other hospitals.Finally,our findings may be controversial because the sample size failed to meet initial expectations, raising questions about whether the study was underpowered.Published studies suggested the tolerance rate is about 84.6% for NG feeding [36],and 95.6% for NJ tube [20].With 5% level of significance(2-sided) and 80% power, the estimated sample size should be more than 112 patients in each group.Thus, a larger sample may provide more precise and more definitive insights into the effect of NG feeding.

In conclusion, EN has its role in the management of pediatric patients with AP and can be well provided by NG or NJ feeding.Although the evidence is not convincing, the NG feeding is not inferior to the NJ feeding in tolerance.Signifi-cantly, NG feeding can result in decreases in the tube feeding time and length of hospital stay.EN administered by NG route can be an alternative to NJ route with equal efficacy and safety.Additional high-quality, large-scale randomized controlled studies are necessary to validate the routine use of NG tubes in pediatric AP patients.

AcknowledgementsWe thank the statisticians from the Statistics Department of the Children’s Hospital Affiliated to Zhejiang University School of Medicine, for their help in data analysis.

Author contributionsZH and HY contributed equally as co-first authors.ZH and HY conceptualized and designed the study, collected data, analyzed and interpreted the data, drafted the initial manuscript, reviewed and revised the manuscript.PKR, LYY, YJD,and FYH analyzed and interpreted the data, drafted the initial manuscript.CJ and LJG conceptualized and designed the study, coordinated and supervised data collection, and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content.All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FundingThis work was supported by Scientific Research Fund of Zhejiang Provincial Education Department (Y201738367).The funder/sponsor did not participate in the work.

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethical approvalThe study was approved by Ethics Committee of the Children’s Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine.Informed consents to participate in the study have been obtained from participants and their legal guardians.Chinese Clinical Trial Registry,ChiCTR-TRC-14004511 ( http://www.chictr.org.cn/showp roj.aspx?proj= 5061 ).

Conflict of interestNofinancial or non-financial benefits have been received or will be received from any party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Data availabilityThe datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

World Journal of Pediatrics2021年5期

World Journal of Pediatrics2021年5期

- World Journal of Pediatrics的其它文章

- Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis as a manifestation of Kawasaki disease

- Febrile infants: written guidelines to reduce non-essential hospitalizations

- Rising serum potassium and creatinine concentrations after prescribing renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system blockade:how much should we worry?

- Role of ultrasound in the diagnosis of cervical tuberculous lymphadenitis in children

- Pediatric upper extremity firearm injuries: an analysis of demographic factors and recurring mechanisms of injury

- Serum vitamin E concentration is negatively associated with body mass index change in girls not boys during adolescence